Abstract

Objectives

To quantify the relationship between meteorological factors and bacillary dysentery incidence.

Design

Ecological study.

Setting

We collected bacillary dysentery incidences and meteorological data of Chaoyang city from the year 1981 to 2010. The climate in this city was a typical northern temperate continental monsoon. All meteorological factors in this study were divided into 4 latent factors: temperature, humidity, sunshine and airflow. Structural equation modelling was used to analyse the relationship between meteorological factors and the incidence of bacillary dysentery.

Material

Incidences of bacillary dysentery were obtained from the Center for Disease Control and Prevention of Chaoyang city, and meteorological data were collected from the Bureau of Meteorology in Chaoyang city.

Primary outcome measures

The indexes including χ2, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), comparative fit index (CFI), standardised root mean square residual (SRMR) and goodness-of-fit index (GFI) were used to evaluate the goodness-of-fit of the theoretical model to the data. The factor loads were used to explore quantitative relationship between bacillary dysentery incidences and meteorological factors.

Results

The goodness-of-fit results of the model showing that RMSEA=0.08, GFI=0.84, CFI=0.88, SRMR=0.06 and the χ2 value is 231.95 (p=0.0) with 15 degrees of freedom. Temperature and humidity factors had positive correlations with incidence of bacillary dysentery, with the factor load of 0.59 and 0.78, respectively. Sunshine had a negative correlation with bacillary dysentery incidence, with a factor load of −0.15.

Conclusions

Humidity and temperature should be given greater consideration in bacillary dysentery prevention measures for northern temperate continental monsoon climates, such as that of Chaoyang.

Keywords: Bacillary dysentery, Meteorological factors, Structural equation modeling

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study included multiple meteorological factors which can produce a better forecast of high-risk environments for dysentery epidemics than using a single factor alone.

The effects of meteorological variables on the incidence of bacillary dysentery were not comprehensively analysed as an all-inclusive model in previous studies, and we used structural equation modelling to clearly quantify the integrated effect of various meteorological factors on bacillary dysentery incidences.

We only used data from 1981 to 2010 in Chaoyang city, and further study should expand the time span and study area to reduce errors and improve accuracy in order to make better the applicability of these results feasible.

Using cross-sectional data in ecological study limited us to confirm the causal relationship and control the confounding factors.

Introduction

Bacillary dysentery, a type of dysentery, is a severe form of shigellosis, with the characteristics of blood in stool. Patients often develop bloody diarrhoea, fever and stomach cramps with an incubation of 1 or 2 days.1 The infection is spread from person to person via oral-feces, food or drinking water.2 Bacillary dysentery is one of the most common causes of diarrhoea, and the estimated annual incidence of Shigella episodes worldwide is about 164.7 million, of which 163.2 million cases have occurred in developing nations, resulting in 1.1 million deaths.3 Although episodes of bacillary dysentery in China have decreased from 1.3 million in 1991 to 0.24 million in 2011, there is still a considerable risk of bacillary dysentery, especially among the youngest and the oldest population groups and those in low economic regions.4 Although there had been a dramatic drop in overall infectious disease outbreaks between 1975 and 1995, it has since then reverted and maintained a gradual upward trend.5 It is reported that bacillary dysentery, one of the top four infectious diseases from 2005 to 2010, presents nearly 500 000 cases each year in China.6 In addition to high incidence rates, bacillary dysentery treatment is severely threatened by the episodic emergence of new antibiotic resistance strands.7 Thus, prevention heavily relies on public health measures, such as water and food sanitation, since there is a lack of safe and efficacious vaccines.

In addition to the heavy burden of bacillary dysentery on public health, a greater worry is the change in the incidence and distribution of infectious diseases that is concomitant with meteorological effects.8 According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, there is estimated to be a 1.1–6.4°C increase in average surface temperature by 2100, an increase 2–9 times higher than the average global warming change during the last century.9 In addition to this temperature increase, it is projected that there will be increase in the frequency and severity of extreme weather conditions such as floods and droughts. Studies show that increase in disease outbreaks and variations can be attributed to this climate change.10–14 For example, in 2000, the increased global burden of diseases, such as diarrhoea and respiratory diseases, due to climate change attributed to over 150 000 deaths worldwide.15

Bacillary dysentery is a foodborne and waterborne infectious disease. The incidences of bacillary dysentery in Chaoyang were not stable in the past few years. From 1981 to 2000, the general trend of incidences was decreased, and the incidence showed a slight increase around 2000, then it reduced and fluctuated, to around 1.5 per million.16 The incidence of bacillary dysentery is related to many factors, including economical status, hygiene, food and water.17 Recently, studies have found associations between climate and bacillary dysentery in light of global warming.18–20 Meteorological factors such as temperature and humidity can affect bacteria reproduction and survival.18 Although a number of studies have addressed these issues, they have focused on a bivariate relationship between observed meteorological variables and incidence of bacillary dysentery rather than the integrated effect of latent meteorological variables. More importantly, few studies have quantified the impact of these meteorological variables. It is important to perform comprehensive quantitative analyses on the effects of meteorological variables on infectious diseases such as bacillary dysentery in order to illustrate trends in the correlations among the different meteorological factors such as temperature, humidity and sunshine. Chaoyang is located in the northwest of Liaoning province and has a northern temperate continental monsoon climate. Affected by the warm moisture from the southeast sea, and the dry cold air from the northern plateau, it has a semiarid subhumid climate, which easily becomes dry. The increasing temperature and decreasing precipitation makes the warm desiccation tendency quite obvious in Chaoyang city.21 Clear assessment of influencing factors on infectious diseases such as bacillary dysentery are necessary to shed light on adaptation strategies, policies and measures to lessen the projected adverse impacts.22

Regression and correlation analysis have been used to study the transmission of bacillary dysentery.23–25 Previous research found that the incidence of bacillary dysentery showed significant correlation with precipitation, relative humidity, pressure and temperature.23 24 Researchers also believed that meteorological indicators could be used to predict incidences of bacillary dysentery.19 25 However, effects of those meteorological endogenous variables on the incidence of bacillary dysentery were not comprehensively analysed as an all-inclusive model, and the impact sizes were not measured in these studies. The limitations of these methods are that some meteorological factors like temperature, sunshine and humidity cannot be clearly quantified. Structural equation modelling (SEM) is a statistical technique for testing and estimating causal relationships using a combination of statistical data and qualitative causal assumptions. SEM has gained much popularity due to its flexibility in experimental design and rigorous approach to model testing. SEM has the advantages of handling multiple dependent variables at one time, analysing indices that cannot be directly measured, etc.26 SEM has recently been applied to studies of infectious diseases.27 28

In this study we used SEM to analyse meteorological factors like temperature, sunshine, airflow and humidity and their impacts on bacillary dysentery incidence and to understand the integrated effect of meteorological factors on the incidence of bacillary dysentery so as to provide valuable suggestions to public health departments when they need to take decisive steps in health awareness and bacillary dysentery prevention.

Materials and methods

Study area

Chaoyang is located in the northwest part of Liaoning province with a population of 3 342 624 in 2000 and 3 399 665 in 2010 (figure 1). The climate is a typical northern temperate continental monsoon climate with four distinctive seasons: spring, March to May; summer, June to August; autumn, September to November; and winter, December to February. Its annual average temperature is about 9.5°C, sunshine time is 2850–2950 hours per year, and the average annual precipitation is limited to 450–580 mm because of its landlocked location. It extends between longitude 118′50″–121′17″ and latitude 40′25″–42′22″, stretching 165 km horizontally and 216 km vertically. The dry cold air from the Mongolian Plateau often descends on the area, forming a semidry and semihumid climate with little precipitation. Drought often occurs in the spring and autumn.

Figure 1.

Location of Chaoyang city. Chaoyang is located in the northwest part of Liaoning province, and the climate is a typical northern temperate continental monsoon climate.

Data collection

The time frame chosen for this study was from 1981 to 2010. We obtained data on monthly incidences of bacillary dysentery through the Center for Disease Control and Prevention of Chaoyang city. Monthly meteorological data were collected from the Bureau of Meteorology in Chaoyang city. First, a logarithmic transformation of bacillary dysentery incidence was performed to normalise the distribution. Second, Pearson's correlation was conducted to explore the relevancy between meteorological variables and the monthly incidence of bacillary dysentery with a lag of 0–3 months. SEM was used to assess the independent effects of meteorological variables on the incidence of bacillary dysentery.

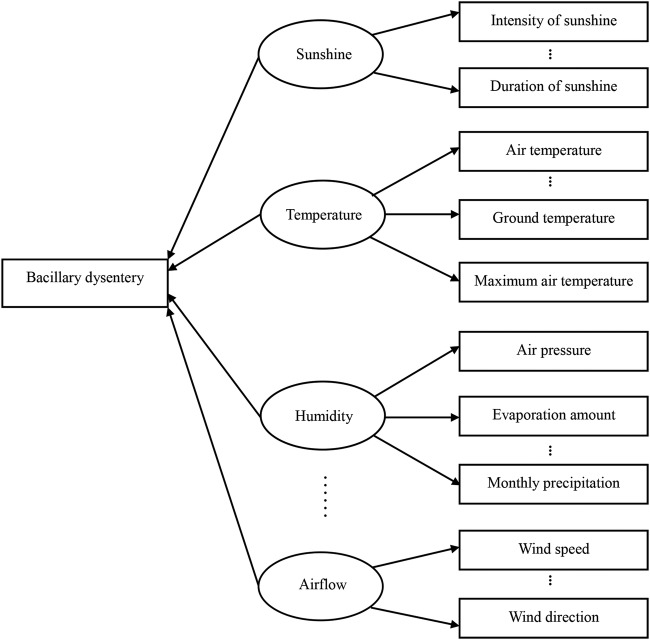

We built the hypothesis model which included four latent meteorological factors: temperature, humidity, sunshine and airflow. The temperature factor included average air temperature, maximum air temperature, minimum air temperature, average ground temperature, maximum ground temperature and minimum ground temperature. The humidity factor included monthly average evaporation amount, absolute humidity, relative humidity, maximum frozen soil depth, air pressure, number of non-precipitation days, maximum precipitation, precipitation, maximum depth of snow cover and maximum number of snow cover days. The sunshine factor included monthly average intensity of sunshine, average percentage of sunshine and average duration of sunshine, and the airflow factor included monthly average wind speed and wind direction.

Given that independency of observed variables should be a vital precondition for the application of SEM, the collinearity diagnostic was carried out. The results showed that some observed variables were not independent of each other. In order to adjust for this, the principal component factor analysis was conducted. Two factors from temperature observed variables were extracted, which were defined as ground temperature and air temperature, respectively. And the exploratory factor analysis identified four latent factors accounting for 72.89% of the total observed variables.

Construction of the SEM

SEM includes both the measurement model and the structural model.29–31 The whole model is based on relationships among observed variables and latent factors. In this study, the latent factors such as temperature and sunshine are listed in circles, while the observed variables are in rectangles. All of the observed variables were fit to the linear analysis. There were six main steps in the establishment of SEM: developing a theoretical model, constructing a path diagram of causal relationships, converting the path diagram into a set of structural equations and specifying a measurement model, fitting the proposed model, evaluating goodness-of-fit criteria, and interpreting and modifying the model.

Statistical analysis

SPSS V.13.0 software was used to predetermine meteorological factors in the study. Factor analysis was carried out to test for structural validity. LISREL V.8.5 was used to construct SEM. LISREL provided different goodness-of-fit measures. Goodness-of-fit in the present study was usually measured on the basis of χ2 test, goodness-of-fit index (GFI), comparative fit index (CFI), standardised root mean square residual (SRMR) and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). The χ2 test had traditionally been used to test the hypothesis of the relationships suggested in the hypothetical model. The rest of the values range between 0.0 and 1.0, with GFI, CFI values closer to 1.0 and RMSEA, SRMR values closer to 0.0 indicating good fit.

Results

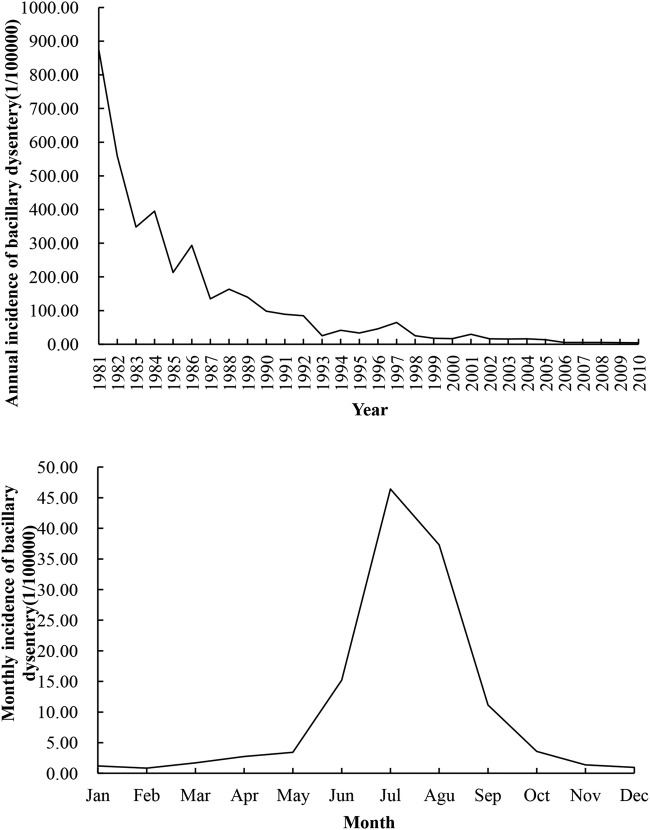

The data of incidences and meteorological factors were collected from 1981 to 2010, which means that for the incidences and each factor there are 360 samples. Annual and monthly incidences of bacillary dysentery from 1981 to 2010 are shown in figure 2. Pearson's correlation analysis showed that temperature, humidity and sunshine factors were related to the monthly bacillary dysentery incidence at the highest level with a lag of 1 month. This result is consistent with other studies on meteorological variables and intestinal infectious diseases that have found an average lagged effect of 1 month.20 The time lag would capture the virus incubation period within the human body and from the onset of the bacillary dysentery to notification to the healthcare system.27

Figure 2.

Annual and monthly incidence of bacillary dysentery (Chaoyang city, China, 1981–2010).

The initial diagram of causal relationships is presented in figure 3. The apostrophe represents the meteorological factors that are not listed here. The circles represent the latent variables, while the rectangles show the observed variables. A certain variable affects others with the direction of the arrow.

Figure 3.

A hypothetical structural equation modelling of meteorological factors and bacillary dysentery. The apostrophe represents the meteorological factors that are not listed here. The circles represent the latent variables, while the rectangles show the observed variables. A certain variable affects others with the direction of the arrow.

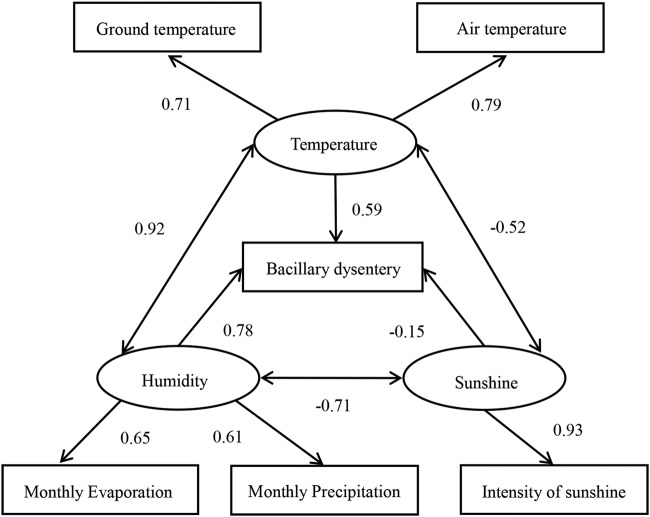

The SEM fitting results showed that RMSEA=0.08, GFI=0.84, CFI=0.88 and SRMR=0.06. The χ2 value was 231.95 (p=0.0) with 15 degrees of freedom. The model produced an acceptable fit to the sample data. The results of SEM confirmed that all relevant meteorological indicators in this study were divided into three latent factors, temperature, humidity and sunshine. Factors like temperature and humidity had positive correlations with incidence of bacillary dysentery, with the factor load of 0.59 and 0.78, respectively. Sunshine had a negative correlation with bacillary dysentery incidence, with a factor load of −0.15 (figure 4). The effects of meteorological factors shown in figure 4 were confirmed by our study on bacillary dysentery. All the results here were completely standardised solutions.

Figure 4.

Structural equation modelling of meteorological factors and bacillary dysentery. Temperature and humidity factors had positive correlations with incidence of bacillary dysentery, with the factor loads of 0.59 and 0.78, respectively. The sunshine factor had a negative correlation with the incidence of bacillary dysentery, with a factor load of −0.15.

For the temperature factor, air temperature was the most influential factor, with item loading between temperature of 0.79. This was followed by ground temperature, with respective item load of 0.71. This suggested that air temperature may be the most effective to predict the impact of temperature on bacillary dysentery. For the humidity factor, monthly average evaporation and precipitation influenced the incidence of bacillary dysentery, with respective item loads of 0.65 and 0.61, which suggested an emphasis on evaporation. Sunshine factor was mainly composed of only one item: intensity of sunshine, the item load of which was 0.93.

Figure 4 shows that meteorological indicators correlated with the incidence of bacillary dysentery. The effect of meteorological variables on bacillary dysentery incidence was calculated by multiplying the load between the observed variable and latent factor and the load between the latent factor and disease incidence. For example, monthly evaporation has a positive effect on the incidence of bacillary dysentery, with load of 0.51, which was calculated by multiplying 0.65 and 0.78. The results of calculation showed that the observed variables with greater effects on bacillary dysentery were monthly average evaporation, precipitation and air temperature, with item effects of 0.51, 0.48 and 0.47, respectively. The factor loads between meteorological variables and bacillary dysentery incidence are shown in table 1.

Table 1.

The factor loads between meteorological variables and bacillary dysentery incidence in Chaoyang city from 1981 to 2010

| Humidity | Monthly evaporation | Monthly precipitation | Temperature | Ground temperature | Air temperature | Sunshine | Sunshine intensity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacillary dysentery incidence | 0.78** | 0.51** | 0.48** | 0.59** | 0.42** | 0.47** | −0.15** | −0.14** |

**p<0.01.

Discussion

Global warming has far-reaching effects on public health and infectious diseases outbreaks.32–37 Recent studies of global warming have forecasted an increase in heat wave patterns, droughts and inclement weather cycles in many regions of the world.33 34 Incremental heat may give rise to increased likelihood of food pathogens and waterborne diseases.35 36 The results of Gilbreath37 showed that the risk of diarrhoea caused by global warming was ∼10% higher in some regions in Africa and Southeast Asia compared with when no climate change occurred. Therefore, public health is particularly vulnerable to climate change, and health policymakers need a variety of approaches in controlling infectious diseases especially in drought-affected regions.

In the present study, we used SEM to evaluate the influence of meteorological factors on the incidence of bacillary dysentery in Chaoyang city, a drought-prone region, China. There have been many studies on the impact of meteorological variables on bacillary dysentery. However, these studies have overlooked the interaction between different meteorological factors and incidences of bacillary dysentery. The results of SEM in this study are based on an all-inclusive model and take into consideration the comprehensive effects of meteorological factors and meteorological indicators on the incidence of bacillary dysentery. The goodness-of-fit statistics mean that SEM was suitable for understanding such relational data in multivariate systems. The final SEM indicated that three meteorological factors: temperature, humidity and sunshine affected the incidence of bacillary dysentery, but factors like humidity and temperature had greater effect and should be paid closer attention in the study area. The observed meteorological variables like monthly average evaporation, precipitation and air temperature had greater impact on the incidence of bacillary dysentery.

In this study, we found a positive correlation between temperature and incidence of bacillary dysentery. This finding is consistent with other studies on bacillary dysentery, as well as studies on other foodborne diseases such as salmonellosis and typhoid.18–20 38 39 Studies in northern cities of China have shown that a 1°C increase in maximum or minimum temperature is associated with an up to 12% increase in cases of bacillary dysentery.19 20 In this study, we examined two specific temperature parameters as well as their quantitative effects on bacillary dysentery. Of these two parameters, air temperature was the most influential factor with item effect of 0.47. Temperature could affect the reproduction of bacteria especially water reservoirs. It could cause food shortage for humans as well as an increased risk of food contamination.38 In addition, increase in heat and temperature can strongly influence the immune system and individual behaviour.40 41

Our results also showed a positive relationship between humidity and bacillary dysentery. This was consistent with some other studies.18–20 39 42 Monthly evaporation and precipitation have major effect on bacillary dysentery, with factor loads of 0.51 and 0.48. A study in two coastal cities in China showed that the monthly incidence of dysentery was positively correlated with rainfall and humidity.18 A study in Taiwan showed that daily precipitation levels were significantly correlated with all eight notifiable infectious diseases, including waterborne and vectorborne infectious diseases.39 Thus, the local meteorological conditions should be seriously considered for public health interventions on reducing future risks of bacillary dysentery. And the 1-month lagged effect also should be taken into account.

Studies in Europe, Australia, the USA and Peru have examined the association between diarrhoeal diseases and climate variation.43 44 The results showed that weather conditions, such as temperature, rainfall and humidity, could result in an increased incidence of foodborne and waterborne diseases. However, the effects of these meteorological variables are not consistent in some published studies, which could be due to local meteorological conditions, population and ecological characteristics in different regions. Drought, excess rainfall and flooding can also contribute to epidemics of waterborne infectious diseases due to poor sanitation resulting from runoff from overwhelmed sewage lines or the contamination of water by livestock.45 Owing to the arid climate in Chaoyang, drought is relatively common. Large amount of evaporation may affect access to safe drinking water, increase contaminant concentration in the water, or increase ways of usage of a particular body of water.15 44 The results of our study suggest that due attention should be paid to the humidity factor and its effects on bacillary dysentery. Further studies should focus on the effect of humidity indicators on bacillary dysentery transmission in drought-prone areas.

In addition to temperature and humidity, we also found a negative correlation between sunshine and bacillary dysentery. The intensity of sunshine had a negative effect on the incidence of bacillary dysentery, with an item effect of −0.14, and plays an exclusive role in the impact of sunshine on bacillary dysentery. This implies that intensity of sunshine should be taken into account in the prediction of bacillary dysentery. Though there are few studies focusing on sunshine and incidences of infectious diseases, our results indicated that sunshine could have possible effects on bacillary dysentery in the study area. Further understanding of sunshine on bacillary dysentery outbreaks may be needed.

This study provides data ranges to inform public health departments prior to bacillary dysentery outbreaks so that effective measures could be taken to mitigate a bacillary dysentery epidemic. Since this study includes multiple meteorological indicators, it can produce a better forecast of high-risk environments for dysentery epidemics than using a single factor alone. In addition, this understanding of meteorological factors' association with bacillary dysentery can contribute to the current health policy assessment and the development of effective bacillary dysentery control strategies.

Our study also had some limitations. First, the study was conducted in only one Chinese city, which may partly limit the representation of this study sample. Further studies in more areas of China will determine whether these findings can be generalised. Second, using cross-sectional data in ecological study limited us to confirm the causal relationship and control the confounding factors. Additionally, GFIs can only reveal the reality that the hypothesised SEM is compatible with collected data, and the possibility of more plausible SEMs cannot be ruled out.

Conclusion

Temperature, sunshine and humidity are factors that have correlations with the incidence of bacillary dysentery. More specifically, monthly average evaporation, precipitation and air temperature have greater effect on the incidence of bacillary dysentery. They should be given greater consideration in bacillary dysentery prevention measures for northern temperate continental monsoon climates, such as that of Chaoyang.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Center for Disease Control and Prevention of Chaoyang city for access to the survey data. We gratefully acknowledge Peng Guan and Desheng Huang for the theoretical discussions as well as practical advice on the analysis of the data.

Footnotes

Contributors: BQ designed and carried out the studies and performed the statistical analysis. YZ participated in the data analysis and drafted the manuscript. YxZ participated in the data collection. ZZ participated in coordination and helped polish the article.

Funding: Supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, No. 81273186 and No. 30700690.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Niyogi SK. Shigellosis. J Microbiol 2005;43:133–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Levine MM. Bacillary dysentery: mechanisms and treatment. Med Clin North Am 1982;66:623–38. 10.1016/S0025-7125(16)31411-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Qu F, Bao C, Chen S et al. . Genotypes and antimicrobial profiles of Shigella sonnei isolates from diarrheal patients circulating in Beijing between 2002 and 2007. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2012;74:166–70. 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2012.06.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang XY, Tao F, Xiao D et al. . Trend and disease burden of bacillary dysentery in China (1991–2000). Bull World Health Organ 2006;84:561–8. 10.2471/BLT.05.023853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang L, Wilson DP. Trends in notifiable infectious diseases in China: implications for Surveillance and Population Health Policy. PLoS ONE 2012;7:e31076 10.1371/journal.pone.0031076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Qiu S, Wang Z, Chen C et al. . Emergence of a novel Shigella flexneri serotype 4s strain that evolved from a serotype X variant in China. J Clin Microbiol 2011;49:1148–50. 10.1128/JCM.01946-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wong MR, Reddy V, Hanson H et al. . Antimicrobial resistance trends of Shigella serotypes in New York City, 2006–2009. Microb Drug Resist 2010;16:155–61. 10.1089/mdr.2009.0130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang Y, Deng T, Yu S et al. . Effect of meteorological variables on the incidence of hand, foot, and mouth disease in children: a time-series analysis in Guangzhou, China. BMC Infect Dis 2013;13:134 10.1186/1471-2334-13-134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bai L, Morton LC, Liu Q. Climate change and mosquito-borne diseases in China: a review. Global Health 2013;9:10 10.1186/1744-8603-9-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Laaksonen S, Pusenius J, Kumpula J et al. . Climate change promotes the emergence of serious disease outbreaks of filarioid nematodes. Ecohealth 2010;7:7–13. 10.1007/s10393-010-0308-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patz JA, Engelberg D, Last J. The effects of changing weather on public health. Annu Rev Public Health 2000;21:271–307. 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.21.1.271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Patz JA, Epstein PR, Burke TA et al. . Global climate change and emerging infectious diseases. JAMA 1996;275:217–23. 10.1001/jama.1996.03530270057032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rakotomanana F, Ratovonjato J, Randremanana RV et al. . Geographical and environmental approaches to urban malaria in Antananarivo (Madagascar). BMC Infect Dis 2010;10:173 10.1186/1471-2334-10-173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lipp EK, Huq A, Colwell RR. Effects of global climate on infectious disease: the cholera model. Clin Microbiol Rev 2002;15:757–70. 10.1128/CMR.15.4.757-770.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sheffield PE, Landrigan PJ. Global climate change and children's health: threats and strategies for prevention. Environ Health Perspect 2011;119:291–8. 10.1289/ehp.1002233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Health and Family Planning Commission of Liaoning Province. Liaoning health statistical yearbook. Beijing: China Statistics Press, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen KC, Lin CH, Qiao QX et al. . The epidemiology of diarrhoeal diseases in southeastern China. J Diarrhoeal Dis Res 1991;9:94–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang Y, Bi P, Hiller JE et al. . Climate variations and bacillary dysentery in northern and southern cities of China. J Infect 2007;55:194–200. 10.1016/j.jinf.2006.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang Y, Bi P, Hiller JE. Weather and the transmission of bacillary dysentery in Jinan, northern China: a time-series analysis. Public Health Rep 2008;123:61–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang D, Guan P, Guo J et al. . Investigating the effects of climate variations on bacillary dysentery incidence in northeast China using ridge regression and hierarchical cluster analysis. BMC Infect Dis 2008;8:130 10.1186/1471-2334-8-130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li DD. Research of the warming and drying of the climate in Chaoyang from 1960 to 2009. J Qiqihar Univ 2013;23:73–5. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ebi KL, Kovats RS, Menne B. An approach for assessing human health vulnerability and public health interventions to adapt to climate change. Environ Health Perspect 2006;114:1930–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ma SL, Tang QL, Liu HW et al. . Correlation analysis for the attack of bacillary dysentery and meteorological factors based on the Chinese medicine theory of Yunqi and the medical-meteorological forecast model. Chin J Integr Med 2013;19:182–6. 10.1007/s11655-012-1239-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yan L, Fang LQ, Huang HG et al. . Landscape elements and Hantaan virus-related hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome, People's Republic of China. Emerg Infect Dis 2007;13:1301–6. 10.3201/eid1309.061481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu RJ, Hu XS, Zheng YF et al. . The correlation analysis between hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome (HFRS) and meteorological factors and forecast of HFRS. Chin J Vector Bio Control 2005;16:118–20. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Levine SZ, Petrides KV, Davis S et al. . The use of structural equation modeling in stuttering research: concepts and directions. Stammer Res 2005;1:344–63. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guan P, Huang D, He M et al. . Investigating the effects of climatic variables and reservoir on the incidence of hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome in Huludao City, China: a 17-year data analysis based on structure equation model. BMC Infect Dis 2009;9:109 10.1186/1471-2334-9-109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Detilleux J, Theron L, Duprez J-N et al. . Structural equation models to estimate risk of infection and tolerance to bovine mastitis. Genet Sel Evol 2013;45:6 10.1186/1297-9686-45-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. 3rd edn New York: Guilford Press, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kelloway EK. Using LISREL for structural equation modeling: a researcher's guide. SAGE Publications, Incorporated, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Byrne BM. Structural equation modeling with LISREL, PRELIS, and SIMPLIS: basic concepts, applications, and programming. Psychology Press, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Diaz JH. The influence of global warming on natural disasters and their public health outcomes. Am J Disaster Med 2007;2:33–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Saniotis A, Bi P. Global warming and Australian public health: reasons to be concerned. Aust Health Rev 2009;33:611–17. 10.1071/AH090611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Patz JA, Campbell-Lendrum D, Holloway T et al. . Impact of regional climate change on human health. Nature 2005;438:310–17. 10.1038/nature04188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McMichael A, Githeko A. Human health. Climate change 2001: impacts, adaptation and vulnerability. Contributions of the Working Group II to the third assessment of the intergovernmental panel on climate change. Edited by: McCarthy JJ, Leary NA, Canziani OF, Dokken DJ, White KS. 2001, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 36.McMichael AJ, Woodruff RE, Whetton P. Human health and climate change in Oceania: a risk assessment. Canberra, Australia: Commonwealth Department of Health and Aging, 2003:116. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gilbreath J. Climate change—global warming kills. Environ Health Perspect 2004;112:A160–A160. 10.1289/ehp.112-a160a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.D'Souza RM, Becker NG, Hall G et al. . Does ambient temperature affect foodborne disease? Epidemiology 2004;15:86–92. 10.1097/01.ede.0000101021.03453.3e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen MJ, Lin CY, Wu YT et al. . Effects of extreme precipitation to the distribution of infectious diseases in Taiwan, 1994–2008. PLoS ONE 2012;7:e34651 10.1371/journal.pone.0034651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chan EYY, Goggins WB, Kim JJ et al. . Help-seeking behavior during elevated temperature in Chinese population. J Urban Health 2011;88:637–50. 10.1007/s11524-011-9599-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Semenza JC, Wilson DJ, Parra J et al. . Public perception and behavior change in relationship to hot weather and air pollution. Environ Res 2008;107:401–11. 10.1016/j.envres.2008.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guan P, Huang D, Guo J et al. . Bacillary dysentery and meteorological factors in Northeastern China: a historical review based on classification and regression trees. Jpn J Infect Dis 2008;61:356–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kovats RS, Edwards SJ, Hajat S et al. . The effect of temperature on food poisoning: a time-series analysis of salmonellosis in ten European countries. Epidemiol Infect 2004;132:443–53. 10.1017/S0950268804001992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tam CC, Rodrigues LC, O'Brien SJ et al. . Temperature dependence of reported Campylobacter infection in England, 1989–1999. Epidemiol Infect 2006;134:119–25. 10.1017/S0950268805004899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shuman EK. Global climate change and infectious diseases. Int J Occup Environ Med 2011;2:11–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]