Abstract

Objective

To assess the usage patterns of epidural injections for chronic spinal pain in the fee-for-service (FFS) Medicare population from 2000 to 2014 in the USA.

Design

A retrospective cohort.

Methods

The descriptive analysis of the administrative database from Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Physician/Supplier Procedure Summary (PSPS) master data from 2000 to 2014 was performed. The guidance from Strengthening the Reporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) was applied. Analysis included multiple variables based on the procedures, specialties and geography.

Results

Overall epidural injections increased 99% per 100 000 Medicare beneficiaries with an annual increase of 5% from 2000 to 2014. Lumbar interlaminar and caudal epidural injections constituted 36.2% of all epidural injections, with an overall decrease of 2% and an annual decrease of 0.2% per 100 000 Medicare beneficiaries. However, lumbosacral transforaminal epidural injections increased 609% with an annual increase of 15% from 2000 to 2014 per 100 000 Medicare population.

Conclusions

Usage of epidural injections increased from 2000 to 2014, with a decline thereafter. However, an escalating growth has been seen for lumbosacral transforaminal epidural injections despite numerous reports of complications and regulations to curb the usage of transforaminal epidural injections.

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This assessment of usage patterns of epidural injections has been conducted to describe the characteristics of all types of epidural injections in managing chronic spinal pain in the fee-for-service (FFS) Medicare population in the USA from 2000 to 2014.

The strengths of this assessment include use of 100% FFS Medicare population including those above and below 65 years of age.

One of the limitations is that the study is restricted to only the Medicare population and patients with Medicare Advantage plans have not been included which constitute between 20% and 30% of the population.

Additionally, while these results can be generalised to a great extent, caution must be exercised since in other population groups the usage might be materially different.

Introduction

The reports of neurological complications from epidural injections have taken centre stage in the USA1–7 and in other parts of the world over the years.8 Even though the basis for such alarm and subsequent regulatory atmosphere has been criticised,4–7 the explosive increase of numerous modalities to manage spinal pain including epidural injections and the economic impact have provided ammunition for such an atmosphere.9–18 Reports from the US Burden of Disease Collaborators19 and from other parts of the world20 21 have shown spinal pain occupying three of the five top categories of disability. In addition, the prevalence of chronic impairing low back pain has increased in one report 162% from 1992 to 2006, increasing from 3.9% to 10.2%.22 Further, multiple assessments also have shown the chronicity of spinal pain long after its onset.23 24 The evidence of increasing burden of disease and disability across the globe coupled with increasing numbers of treatments have created an unacceptable situation with economic, social and healthcare impact. Further complicating this circumstance is the widely debated issues of efficacy of these interventions.24–40

The statistics show that epidural injections, including percutaneous adhesiolysis procedures, are the most commonly performed procedures in managing spinal pain among interventional techniques, varying from 58.6% in 2000 to 45.2% in 2014 of all interventional techniques.15 The usage of epidural procedures, excluding percutaneous adhesiolysis, showed an overall increase of 165% or 96% per 100 000 fee-for-service (FFS) Medicare beneficiaries with an annual increase of 7.2% or 4.9% from 2000 to 201415 showing a slight decrease compared to 2000 to 2013, from a rate of 105.6% to an annual increase of 5.7%. Interlaminar epidural injections have increased at a slower pace. Among the epidural injections, continuous epidural injections with catheterisation and neurolytic epidural procedures have not been used in managing chronic spinal pain. Manchikanti et al,11–14 in assessing Medicare FFS population in the USA from 2000 to 2013, showed an increase of 119% for cervical and thoracic interlaminar epidural injections and 11% for lumbosacral interlaminar and caudal epidural injections per 100 000 Medicare population with an annual increase of 6.2% or 0.8%, respectively. Contrasting these milder increases, they determined an explosive increase of 577% for lumbosacral transforaminal epidural injections and an 84% increase of cervical and thoracic transforaminal epidural injections per 100 000 Medicare population with an annual increase of 15.8% and 4.8%, respectively, during the same period.11 12 14 Thus, the use of epidural injections has risen dramatically, despite discordant opinions of their effectiveness and their association with rare, but catastrophic complications.24–44

This study is undertaken with an aim of assessing the usage patterns and patterns of use of epidural injections in Medicare FFS population in the USA with the analysis of data from 2000 to 2014.

Methods

Approval by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) was not sought for this assessment as all analysis encompassed public use files (PUF) or non-identifiable data, which is non-attributable and non-confidential, available through the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) database.45 The study was performed using Strengthening the Reporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidance.46

Study design

The study was designed to assess usage patterns of epidural injections, excluding continuous epidurals and neurolytic procedures, which constitute a small proportion used for chronic management, in the FFS Medicare population in the USA from 2000 to 2014.

Setting

National database of specialty usage data files from CMS, USA, FFS Medicare.45

Participants

Participants included the FFS Medicare recipients from 2000 to 2014.

For analysis, the current procedure codes for epidural injections were used. The CPT codes used included epidural codes CPT 62310, 62311 and transforaminal epidural codes CPT 64479, 64480, 64483 and 64484. These codes were identified for years 2000 to 2014. Subsequently, usage data were assessed based on the place of service, either the facility which included ambulatory surgery centres and hospital outpatient departments (HOPDs), or a non-facility setting—the office. The data are calculated for overall services for each technique, and the rate of services for 100 000 Medicare beneficiaries, and also based on the specialty.

Variables

Multiple characteristics are assessed in this evaluation of the Medicare population and increase in the Medicare population from 2000 to 2014, usage of epidural procedures in the cervical, thoracic, lumbar and sacral spine. Additional characteristics assessed included various specialty designations and the settings in which the procedures were performed.

The description of various specialties was as follows: multiple specialties representing interventional pain physicians including interventional pain management −09, pain medicine −72, anaesthesiology −05, physical medicine and rehabilitation −25, neurology −13, psychiatry −26 were described as interventional pain management. Surgical specialties included orthopaedic surgery −20, general surgery −17 and neurosurgery −14. Radiologic specialties included diagnostic radiology −30 and −94 interventional radiology. All other physicians were grouped into a separate group (general physicians), and all other non-physician providers were considered as other providers.

Data sources

The data were obtained from the CMS physician supplier procedure summary master data from 2000 through 2014.45 These data provide all FFS Medicare participants below the age of 65 and above the age of 65 receiving epidural procedures.

Measures

Allowed services were calculated from services submitted minus services denied and services with zero payments.

Allowed services were assessed for each procedure, and rates were calculated based on Medicare beneficiaries for the corresponding year and are reported as procedures per 100 000 Medicare beneficiaries.

Bias

The study was conducted with the internal resources of the primary author's practice without any external funding, either from industry or elsewhere. The data were purchased from CMS by the American Society of Interventional Pain Physicians (ASIPP). CMS's 100% data set consists of usage by CPT code with modifier usage (as an additional procedure or bilateral procedure), specialty codes, place of service, Medicare carrier number, total services and charges submitted, allowed and denied, and amount paid.

Study size

The study size is large with inclusion of all patients under Medicare FFS undergoing epidural procedures for spinal pain from 2000 to 2014.

Data compilation

The data were compiled using Microsoft Access 2003 and Microsoft Excel 2003 (Microsoft, Redmond, Washington, USA).

Results

Participants

Participants included the FFS Medicare recipients from 2000 to 2014.

Descriptive data

Table 1 illustrates the characteristics of Medicare beneficiaries as well as the epidural injections provided to them. Medicare beneficiaries increased 35% from 2000 to 2014 compared to an increase of 99% in the rate (per 100 000 Medicare beneficiaries) of epidural injections with an annual increase of 5% compared to a 2.2% annual increase in the number of Medicare beneficiaries which is 2.6 times the increase of the population rate.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Medicare beneficiaries and epidural procedures excluding percutaneous adhesiolysis, continuous epidurals and neurolytic epidurals.

| US population |

Medicare beneficiaries |

Epidural services* |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≥65 years (,000) |

|||||||||||

| Total population (,000) | Number | Per cent | Number (,000) | Per cent to US population | ≥65 years (,000) (%) | <65 years (,000) % | Services* | Per cent of change from previous year | Per 100 000 Medicare FFS enrollees | Per cent of change from previous year | |

| Y2000 | 282 172 | 35 077 | 12.4 | 39 632 | 14.0 | 34 262 (86.5%) | 5370 (13.5%) | 839 474 (80%) | NA | 2118 | – |

| Y2001 | 285 040 | 35 332 | 12.4 | 40 045 | 14.0 | 34 478 (86.1%) | 5567 (13.9%) | 989 034 (78%) | 17.8 | 2470 | 16.6 |

| Y2002 | 288 369 | 35 605 | 12.3 | 40 503 | 14.0 | 34 698 (85.7%) | 5805 (14.3%) | 1 172 248 (74%) | 18.5 | 2894 | 17.2 |

| Y2003 | 290 211 | 35 952 | 12.4 | 41 126 | 14.2 | 35 050 (85.2%) | 6078 (14.8%) | 1 342 829 (71%) | 14.6 | 3265 | 12.8 |

| Y2004 | 292 892 | 36 302 | 12.4 | 41 729 | 14.2 | 35 328 (84.7%) | 6402 (15.3%) | 1 611 887 (65%) | 20.0 | 3863 | 18.3 |

| Y2005 | 295 561 | 36 752 | 12.4 | 42 496 | 14.4 | 35 777 (84.2%) | 6723 (15.8%) | 1 747 771 (65%) | 8.4 | 4113 | 6.5 |

| Y2006 | 299 395 | 37 264 | 12.4 | 43 339 | 14.5 | 36 317 (83.8%) | 7022 (16.2%) | 1 844 182 (63%) | 5.5 | 4255 | 3.5 |

| Y2007 | 301 290 | 37 942 | 12.6 | 44 263 | 14.7 | 36 966 (83.5%) | 7297 (16.5%) | 1 915 227 (62%) | 3.9 | 4327 | 1.7 |

| Y2008 | 304 056 | 38 870 | 12.8 | 45 412 | 14.9 | 37 896 (83.4%) | 7516 (16.6%) | 2 017 132 (61%) | 5.3 | 4442 | 2.7 |

| Y2009 | 307 006 | 39 570 | 12.9 | 45 801 | 14.9 | 38 177 (83.4%) | 7624 (16.6%) | 2 112 511 (59%) | 4.7 | 4612 | 3.8 |

| Y2010 | 308 746 | 40 268 | 13.0 | 46 914 | 15.2 | 38 991 (83.1%) | 7923 (16.9%) | 2 205 307 (57%) | 4.4 | 4701 | 1.9 |

| Y2011 | 311 583 | 41 370 | 13.3 | 48 300 | 15.5 | 40 000 (82.8%) | 8300 (17.2%) | 2 289 213 (58%) | 3.8 | 4740 | 0.8 |

| Y2012 | 313 874 | 43 144 | 13.8 | 50 300 | 16.0 | 41 900 (83.3%) | 8500 (16.9%) | 2 304 993 (58%) | 0.7 | 4582 | −3.3 |

| Y2013 | 316 129 | 44 704 | 14.1 | 51 900 | 16.4 | 43 100 (83.0%) | 8800 (17.0%) | 2 259 887 (58%) | −2.0 | 4354 | −5.0 |

| Y2014 | 318 892 | 46 179 | 14.5 | 53 500 | 16.8 | 44 600 (83.4%) | 8900 (16.5%) | 2 255 668 (57%) | −0.2 | 4216 | −3.2 |

| Per cent change from 2000 to 2014 | 13.0 | 31.7 | 16.8 | 35.0 | 19.8 | 30.2 | 65.7 | 168.7 | – | 99.0 | |

| Geometric average change %) | 0.9 | 2.0 | 2.2 | 1.9 | 3.7 | 7.3 | – | 5.0 | |||

*Epidural services=62310—cervical/thoracic interlaminar epidural injections; 62311—lumbar/sacral interlaminar epidural injections; 64479—cervical/thoracic transforaminal epidural injections; 64480—cervical/thoracic transforaminal epidural injections add-on; 64483—lumbar/sacral transforaminal epidural injections; 64484—lumbar/sacral transforaminal epidural injections add-on.

Usage characteristics

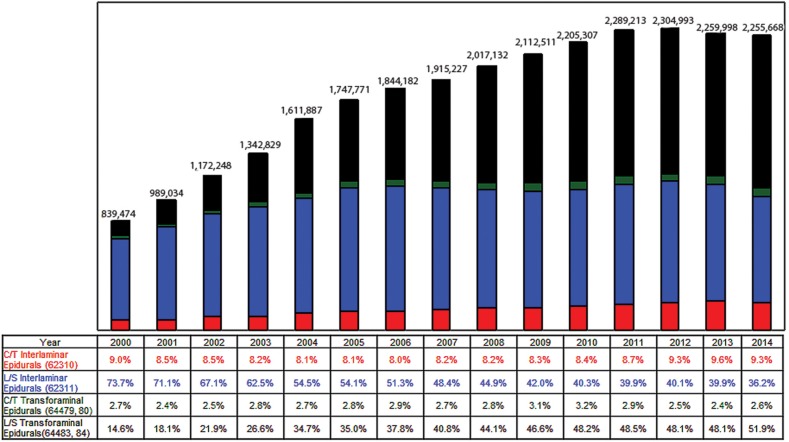

Table 2 and figure 1 illustrate the usage characteristics of epidural injections in the Medicare population from 2000 to 2014. Overall epidural injections increased 99% per 100 000 Medicare beneficiaries with an annual increase of 5%. However, lumbosacral interlaminar and caudal epidural injections (CPT 62311) decreased 2% per 100 000 Medicare beneficiaries with a 0.2% annual decrease compared to an increase of 104% per 100 000 beneficiaries and a 5.2% annual increase for cervical/thoracic interlaminar epidural injections (CPT 62310). In contrast, lumbosacral transforaminal epidural injections (CPT 64483 and 64484) increased 609% per 100 000 population with an annual increase of 15% and cervical/thoracic transforaminal epidural injections (CPT 64479 and 64480) increased 93% with an annual increase of 4.8%. Thus, all the decrease in usage of interlaminar epidural injections were compensated by increases of transforaminal epidural injections in the lumbar spine. In addition, cervical and thoracic transforaminal epidural injections have been decreasing from 2011 to 2013 but have shown an increase in 2014. Using the number of patient episodes providing the services, lumbar/sacral interlaminar or caudal epidural injections (CPT 62311) decreased at a rate of −2% from 2000 to 2014, whereas the rate of usage in 2014 was 815 858 services with 1525 per 100 000 Medicare FFS population with a decrease of 12.2% from the previous year and the decreases observed from 2006 through 2014. In addition, the number of patient episodes with transforaminal epidural injections (CPT 64483) were slightly less with 763 793 services with 1428 per 100 000 Medicare population, with an increase of 15% from 2000 to 2014, with decreases observed in 2 years with 4.0% decrease in 2012 and 5.1% in 2013 with an increase of 4.7% in 2014. In 2000, 1560 patients per 100 000 Medicare population received lumbar and caudal epidural injections, whereas 214 received lumbar transforaminal epidural injections. These numbers decreased for interlaminar epidural injections from 1560 to 1525, whereas lumbar transforaminal epidural injections increased from 214 to 1428 per 100 000 Medicare population.

Table 2.

Utilisations of epidural injections in the fee-for-service Medicare population from 2000 to 2014

| Cervical/thoracic interlaminar epidurals (CPT 62310) |

Lumbar interlaminar and caudal epidurals (CPT 62311) |

Cervical/thoracic transforaminal epidurals |

Lumbar/sacral transforaminal epidurals |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Services | Rate | Per cent of change from previous year | Services | Rate | Per cent of change from previous year | CPT 64479 |

CPT 64480 |

Total | Rate | Per cent of change from previous year | CPT 64483 |

CPT 64484 |

Total | Per cent of change from previous year | ||

| Services | Services | Services | Services | Services | Services | Rate | ||||||||||

| 2000 | 75 741 | 191 | – | 618 362 | 1560 | – | 13 454 | 9434 | 22 888 | 58 | – | 85 006 | 37 477 | 122 483 | 309 | – |

| 2001 | 84 385 | 211 | 10.3 | 702 713 | 1755 | 12.5 | 14 732 | 8537 | 23 269 | 58 | 0.6 | 125 534 | 53 133 | 178 667 | 446 | 44.4 |

| 2002 | 99 117 | 245 | 16.1 | 786 919 | 1943 | 10.7 | 18 583 | 10 835 | 29 418 | 73 | 25.0 | 177 679 | 79 115 | 256 794 | 634 | 42.1 |

| 2003 | 109 783 | 267 | 9.1 | 838 858 | 2040 | 5.0 | 21 882 | 15 769 | 37 651 | 92 | 26.0 | 242 491 | 114 046 | 356 537 | 867 | 36.7 |

| 2004 | 130 649 | 313 | 17.3 | 878 174 | 2104 | 3.2 | 25 182 | 18 094 | 43 276 | 104 | 13.3 | 363 744 | 196 044 | 559 788 | 1341 | 54.7 |

| 2005 | 141 652 | 333 | 6.5 | 945 350 | 2225 | 5.7 | 27 844 | 20 525 | 48 369 | 114 | 9.8 | 395 508 | 216 892 | 612 400 | 1441 | 7.4 |

| 2006 | 146 748 | 339 | 1.6 | 946 961 | 2185 | −1.8 | 29 822 | 23 073 | 52 895 | 122 | 7.2 | 452 125 | 245 453 | 697 578 | 1610 | 11.7 |

| 2007 | 156 415 | 353 | 4.4 | 926 029 | 2092 | −4.3 | 29 938 | 22 266 | 52 204 | 118 | −3.4 | 506 274 | 274 305 | 780 579 | 1764 | 9.6 |

| 2008 | 165 636 | 365 | 3.2 | 905 419 | 1994 | −4.7 | 32 286 | 24 003 | 56 289 | 124 | 5.1 | 572 340 | 317 448 | 889 788 | 1959 | 11.1 |

| 2009 | 175 503 | 383 | 5.1 | 888 166 | 1939 | −2.7 | 37 012 | 27 487 | 64 499 | 141 | 13.6 | 632 658 | 351 685 | 984 343 | 2149 | 9.7 |

| 2010 | 184 750 | 394 | 2.8 | 888 421 | 1894 | −2.3 | 40 003 | 29 888 | 69 891 | 149 | 5.8 | 679 117 | 383 128 | 1 062 245 | 2264 | 5.4 |

| 2011 | 200 134 | 414 | 5.2 | 914 324 | 1893 | 0.0 | 38 970 | 26 628 | 65 598 | 136 | −8.8 | 710 638 | 398 519 | 1 109 157 | 2296 | 1.4 |

| 2012 | 213 390 | 424 | 2.4 | 925 179 | 1839 | −2.8 | 35 945 | 21 293 | 57 238 | 114 | −16.2 | 718 437 | 390 749 | 1 109 186 | 2205 | −4.0 |

| 2013 | 217 393 | 419 | −1.3 | 901 468 | 1737 | −5.6 | 34 699 | 20 409 | 55 108 | 106 | −6.7 | 700 820 | 385 098 | 1 085 918 | 2092 | −5.1 |

| 2014 | 208 741 | 390 | −6.9 | 815 858 | 1525 | −12.2 | 37 944 | 21 587 | 59 531 | 111 | 4.8 | 763 793 | 407 745 | 1 171 538 | 2190 | 4.7 |

| Per cent of change from 2000 to 2014 | ||||||||||||||||

| Change | 176 | 104 | – | 32 | −2 | – | 182 | 129 | 160 | 93 | – | 799 | 988 | 856 | 609 | – |

| Geometric average annual change (%) | ||||||||||||||||

| Geometric average | 7.5 | 5.2 | – | 2.0 | −0.2 | – | 7.7 | 6.1 | 7.1 | 4.8 | – | 17.0 | 18.6 | 17.5 | 15.0 | – |

Rate—per 100 000 Medicare beneficiaries.

Figure 1.

Frequency of usage of epidural injections by procedures from 2000 to 2014, in Medicare recipients.

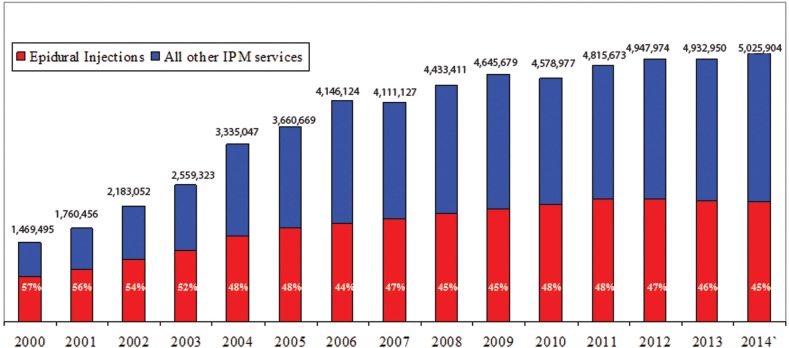

As shown in figure 2, the proportion of epidural injections of all interventional techniques performed reduced 57% to 45% from 2000 to 2014.

Figure 2.

Frequency of usage of epidural injections and all other interventional pain management procedures from 2000 to 2014, in Medicare recipients.

Specialty characteristics

Online supplementary appendices 1 and 2 illustrate the usage of epidural injections by various specialties. In the group of interventional pain management, including anaesthesiology, interventional pain management, pain medicine, physical medicine and rehabilitation, neurology and psychiatry, the rate of increase was 113% per 100 000 Medicare beneficiaries with an overall increase of 99% from 2000 to 2014. However, among these groups, physical medicine and rehabilitation showed an overall increase of 672% and 472% per 100 000 Medicare beneficiaries. Radiology, consisting of interventional radiology and diagnostic radiology, also showed an increasing rate of 167% per 100 000 Medicare beneficiaries from 2000 to 2014. Surgical specialties, including neurosurgery, orthopaedic surgery and general surgery, showed an increase of 58% from 2000 to 2014.

bmjopen-2016-013042supp_appendices.pdf (1.1MB, pdf)

Site of service characteristics

Epidural injections are provided in multiple settings including HOPDs, ambulatory surgical centres (ASCs) and in physician's offices (in-office). There has been a significant shift over the years in epidural injections based on the location of the procedure's performance. In 2002, HOPD services constituted 54.3%, with ASCs providing 19.9% of the service, and in-office providing 25.8%. By 2014, the HOPD share decreased to 29.4%, the ASC share increased to 27.7% and the in-office share dramatically increased to 42.9% as shown in online supplementary appendices 3 and 4.

Main results

Epidural injections increased 99% per 100 000 Medicare beneficiaries with an annual increase of 5% in FFS Medicare beneficiaries from 2000 to 2014. Lumbar interlaminar and caudal epidural injections constituted 36.2% of all epidural injections, with an overall decrease of 2% and an annual decrease of 0.2% per 100 000 Medicare beneficiaries.

Lumbosacral transforaminal epidural injections increased 609% with an annual increase of 15% from 2000 to 2014 per 100 000 Medicare population. However, the ratio of lumbosacral transforaminal epidural injections increased from 14.6% of all epidural injection in 2000 to 51.9% in 2014, thus, exceeding interlaminar epidural injections.

Site-of-service usage patterns showed a decrease in HOPDs associated with a dramatic increase in in-office procedures.

Discussion

Usage of epidural injections for chronic spinal pain in the FFS Medicare population in the USA increased dramatically from 2000 to 2014. The increase for epidural injections has been shown to be 99% per 100 000 Medicare beneficiaries with an annual increase of 5%, compared to the increase of Medicare beneficiaries per 100 000 population of 35% with an annual increase of 2.2% during the same period. The increases were predominantly noted for lumbar transforaminal epidural injections with a 609% increase per 100 000 Medicare population from 2000 to 2014 with an annual increase of 15.0%. The increases were modest with 93% for cervical and thoracic transforaminal epidural injections and 104% for cervical and thoracic interlaminar epidural injections per 100 000 Medicare population. Usage of cervical/thoracic interlaminar epidural injections decreased by 6.9%, from 217 393 to 208 741, from 2013 to 2014 and for lumbar/sacral interlaminar epidural injections 9% from 901 468 to 815 858, whereas there was an 8% increase in cervical/thoracic transforaminal epidural injections from 55 108 to 59 531 and an 8% increase in lumbar/sacral transforaminal epidural injections from 1 085 918 to 1 171 538. Dramatic increases were noted for lumbosacral transforaminal epidural injections from a baseline rate of 309 in 2000 to 2190 in 2014 for per 100 000 Medicare population, an increase of 609% or an annual rate of 15%. In contrast, interlaminar epidural injections in the lumbar spine, which also include caudal epidural injections, have decreased 2% with an annual decrease of 0.2% from 1560 in 2000 per 100 000 Medicare population to 1525 in 2014. Consequently, only interlaminar epidural injections correlated with overall Medicare beneficiary growth, which has been shown to be 35% and growth of Medicare beneficiaries above age 65 years vs below 65 years with 30.2% vs 65.7%. There was also change in site of service usage patterns with a decrease in HOPD use and a dramatic increase in in-office services. ASC share increased from 19.9% in 2002 to 27.7% in 2014 and in-office services dramatically increased from 25.8% in 2002 to 42.9% in 2014 (see online supplementary appendices 3 and 4), whereas HOPD share decreased from 54.3% to 29.4%.

As shown in online supplementary appendices 2 and 3, specialty characteristics showed that an overwhelming majority of the procedures (89.5%) were performed by pain management specialists, which essentially remained stable over the years. Surgery was a distant second specialty with 4.5% and radiology followed with 3.8% usage. Surgical specialties performed fewer procedures when compared to 2000, whereas radiologists performed more procedures. General physicians and other providers including Certified Registered Nurse Anesthetists, nurse practitioners and Physician Assistants also provided a lesser number of epidural injections than in 2000.

The results demonstrated in this evaluation were similar to other recently performed evaluations.11–15 However, these results are noteworthy compared to some of the previous studies, which focused on different aspects rather than assessment of growth and usage.47–49 Friedly et al47 48 and Abbott et al49 indicate that injection therapies were provided with lack of evidence for managing chronic low back pain. Abbott et al49 also included analysis of a publication from the Office of Inspector General in 201050 with multiple recommendations to curb the growth of lumbosacral transforaminal epidurals that showed a lack of significant effect or, at most, mild influence. Another paradoxical development is that transforaminal epidural injections have exceeded the total number of lumbar interlaminar and caudal epidural injections starting in 2009, which essentially reversed a long-standing trend of a high proportion of interlaminar and caudal epidural injections compared to transforaminal epidural injections, despite multiple reports of complications and resultant warnings.1–5 11–15

Some of the limitations for our assessment include lack of inclusion of patients participating in Medicare Advantage Plans, which could lead to exclusion of ∼20–30% of the population. Further, there is also potential for coding errors and elimination of procedures which are not commonly used for spinal pain, such as continuous epidural injections and neurolytic procedures, may underestimate the number of procedures performed. However, the advantages of this study include that we have used the full Medicare data instead of an extrapolation and also all Medicare FFS population instead of using only those 65 years or older.

The increasing prevalence, disability, healthcare costs and human toll of spinal pain, the increasing usage of all modalities, specifically epidural injections—the subject of this assessment—continue to incite controversy and provide the basis of the claims that epidural injections are overused, leading to inappropriate use, abuse and fraud without evidence of efficacy, medical necessity and indications.12 24–26 37 38 The supporters of various modalities continue to profess cautious use with demonstration of effectiveness and cost utility, claim that spinal pain continues to increase, along with its understanding, which continues to evolve over the years.24–36 39 40 51 Thus, epidural injections in managing chronic spinal pain are justified with moderate evidence available in support of these injections in appropriately conducted randomised trials and systematic reviews.12 24–26 37 38 51 However, others have provided contradictory evidence with lack of effectiveness demonstrated in high-profile assessments.25 26 37 These reports have been extensively critiqued.24 27–32 52–56 In addition to substantial differences between proponents and opponents with the majority of the government-sponsored studies in the USA showing lack of effectiveness of epidural injections in managing low back and lower extremity pain, Lewis et al39 40 in two separate manuscripts funded by the National Health Services (NHS) and health technology assessment programme have presented positive results for epidural injections. In a systematic review and economic model of the clinical and cost-effectiveness of management strategies for sciatica performed for the health technology assessment,39 results were positive for demonstrating the effectiveness of epidural corticosteroid injections. They40 also showed, in a systematic review and network meta-analysis of comparative clinical effectiveness of management strategies for sciatica with review of 122 relevant studies and 21 treatment strategies, statistically significant improvement with epidural injections. In addition, network meta-analysis40 also showed superiority of epidural injections to traction, percutaneous discectomy and exercise therapy.

Overall, this assessment shows a continued increase of usage from 2000 to 2011, with subsequent decreasing patterns of usage of epidural injections. However, large-scale and seemingly inappropriate increases in usage are related to lumbar transforaminal epidural injections, whereas there was a net decrease of lumbar interlaminar and caudal epidural injections. Even though epidural injections have constituted smaller increases when compared to other modalities, with continued controversy and the increase of 609% in lumbosacral transforaminal epidural injections from 2000 to 2014, and associated major complications related to transforaminal epidural injections, caution must be exercised in performing these procedures, specifically transforaminal epidural injections. Thus, it is essential not only to develop appropriate evidence, but also to synthesise the evidence using up-to-date randomised controlled trials and proper methodology without confluence of bias. With such analysis of the data, there is no superiority for transforaminal epidural injections compared to interlaminar epidural injections in the lumbar or cervical spine.24 27 29 30 32 57 58

Conclusions

The use of epidural injections escalated from 2000 to 2011 with a small decline since then. However, dramatic increases were shown in usage patterns of lumbar transforaminal epidural injections despite rare complications, warnings and measures reducing the overall impact.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Tom Prigge, MA, and Laurie Swick, BS, for manuscript review; and Tonie M. Hatton and Diane E. Neihoff, transcriptionists, for their assistance in the preparation of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Competing interests: LM has provided limited consulting services to Semnur Pharmaceuticals, Incorporated, which is developing non-particulate steroids. JAH is a consultant for Medtronic.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Rathmell JP, Benzon HT, Dreyfuss P et al. . Safeguards to prevent neurologic complications after epidural steroid injections: consensus opinions from a multidisciplinary working group and national organizations. Anesthesiology 2015;122:974–84. 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.US Food and Drug Administration. Drug Safety Communications. FDA Drug Safety Communication: FDA requires label changes to warn of rare but serious neurologic problems after epidural corticosteroid injections for pain. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/DrugSafety/UCM394286.pdf (accessed 22 Mar 2016).

- 3.Food and Drug Administration. Anesthetic and Analgesic Drug Products Advisory Committee Meeting. November 24–25, 2014. Epidural steroid injections (ESI) and the risk of serious neurologic adverse reactions. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/AdvisoryCommittees/CommitteesMeetingMaterials/Drugs/AnestheticAndAnalgesicDrugProductsAdvisoryCommittee/UCM422692.pdf (accessed 22 Mar 2016).

- 4.Manchikanti L, Candido KD, Singh V et al. . Epidural steroid warning controversy still dogging FDA. Pain Physician 2014;17:E451–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Manchikanti L, Falco FJE, Benyamin RM et al. . Epidural steroid injections safety recommendations by the Multi-Society Pain Workgroup (MPW): more regulations without evidence or clarification. Pain Physician 2014;17:E575–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Manchikanti L, Hirsch JA. Neurological complications associated with epidural steroid injections. Curr Pain Headache Rep 2015;19:482 10.1007/s11916-015-0482-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Manchikanti L, Falco FJE. Safeguards to prevent neurologic complications after epidural steroid injections: analysis of evidence and lack of applicability of controversial policies. Pain Physician 2015;18:E129–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bogduk N, Brazenor G, Christophidis N et al. . Epidural use of steroids in the management of back pain. Report of working party on epidural use of steroids in the management of back pain Canberra, Commonwealth of Australia: National Health and Medical Research Council, 1994:1–76. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rajaee SS, Bae HW, Kanim LE et al. . Spinal fusion in the United States: analysis of trends from 1998 to 2008. Spine 2012;37:67–76. 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31820cccfb [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dart RC, Surratt HL, Cicero TJ et al. . Trends in opioid analgesic abuse and mortality in the United States. N Engl J Med 2015;372:241–8. 10.1056/NEJMsa1406143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Manchikanti L, Pampati V, Falco FJE et al. . Assessment of the growth of epidural injections in the Medicare population from 2000 to 2011. Pain Physician 2013;16:E349–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Manchikanti L, Helm S II, Singh V et al. . Accountable interventional pain management: a collaboration among practitioners, patients, payers, and government. Pain Physician 2013;16:E635–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Manchikanti L, Pampati V, Falco FJE et al. . Growth of spinal interventional pain management techniques: analysis of utilization trends and Medicare expenditures 2000 to 2008. Spine 2013;38:157–68. 10.1097/BRS.0b013e318267f463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Manchikanti L, Pampati V, Falco FJE et al. . An updated assessment of utilization of interventional pain management techniques in Medicare population: 2000–2013. Pain Physician 2015;18:E115–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Manchikanti L, Pampati V, Hirsch JA. Utilization of interventional techniques in managing chronic pain in Medicare population from 2000 to 2014: an analysis of patterns of utilization. Pain Physician 2016;19:E531–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Atluri S, Sudarshan G, Manchikanti L. Assessment of the trends in medical use and misuse of opioid analgesics from 2004 to 2011. Pain Physician 2014;17:E119–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gaskin DJ, Richard P. The economic costs of pain in the United States. J Pain 2012;13:715–24. 10.1016/j.jpain.2012.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martin BI, Turner JA, Mirza SK et al. . Trends in health care expenditures, utilization, and health status among US adults with spine problems, 1997–2006. Spine 2009;34:2077–84. 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181b1fad1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murray CJ, Atkinson C, Bhalla K et al. , US Burden of Disease Collaborators. The state of US health, 1999–2010: burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors. JAMA 2013;310:591–608. 10.1001/jama.2013.13805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hoy D, March L, Brooks P et al. . The global burden of low back pain: estimates from the Global Burden of Disease 2010 study. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:968–74. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoy D, March L, Woolf A et al. . The global burden of neck pain: estimates from the global burden of disease 2010 study. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:1309–15. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Freburger JK, Holmes GM, Agans RP et al. . The rising prevalence of chronic low back pain. Arch Intern Med 2009;169:251–8. 10.1001/archinternmed.2008.543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Manchikanti L, Singh V, Falco FJE et al. . Epidemiology of low back pain in adults. Neuromodulation 2014;17(Suppl 2):3–10. 10.1111/ner.12018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Manchikanti L, Abdi S, Atluri S et al. . An update of comprehensive evidence-based guidelines for interventional techniques in chronic spinal pain. Part II: Guidance and recommendations. Pain Physician 2013;16:S49–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chou R, Hashimoto R, Friedly J et al. . Pain Management Injection Therapies for Low Back Pain. Technology Assessment Report ESIB0813 (prepared by the Pacific Northwest Evidence-based Practice Center under Contract No. HHSA 290–2012-00014-I) Rockville: (MD: ): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 20 March 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pinto RZ, Maher CG, Ferreira ML et al. . Epidural corticosteroid injections in the management of sciatica: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 2012;157:865–77. 10.7326/0003-4819-157-12-201212180-00564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Manchikanti L, Benyamin RM, Falco FJ et al. . Do epidural injections provide short- and long-term relief for lumbar disc herniation? A systematic review. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2015;473:1940–56. 10.1007/s11999-014-3490-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Manchikanti L, Nampiaparampil DE, Candido KD et al. . Do cervical epidural injections provide long-term relief in neck and upper extremity pain? A systematic review. Pain Physician 2015;18:39–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Manchikanti L, Nampiaparampil DE, Manchikanti KN et al. . Comparison of the efficacy of saline, local anesthetics, and steroids in epidural and facet joint injections for the management of spinal pain: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Surg Neurol Int 2015;6:S194–235. 10.4103/2152-7806.156598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Manchikanti L, Kaye AD, Manchikanti KN et al. . Efficacy of epidural injections in the treatment of lumbar central spinal stenosis: a systematic review. Anesth Pain Med 2015;5:e23139 10.5812/aapm.23139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Manchikanti L, Staats PS, Nampiaparampil DE et al. . What is the role of epidural injections in the treatment of lumbar discogenic pain: a systematic review of comparative analysis with fusion. Korean J Pain 2015;28:75–87. 10.3344/kjp.2015.28.2.75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Manchikanti L, Knezevic NN, Boswell MV et al. . Epidural injections for lumbar radiculopathy and spinal stenosis: a comparative systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain Physician 2016;19:E365–410. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu K, Liu P, Liu R et al. . Steroid for epidural injection in spinal stenosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Drug Des Devel Ther 2015;9:707–16. 10.2147/DDDT.S78070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bicket MC, Gupta A, Brown CH et al. . Epidural injections for spinal pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis evaluating the “control” injections in randomized controlled trials. Anesthesiology 2013;119:907–31. 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31829c2ddd [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee J, Gupta S, Price C et al. , British Pain Society. Low back and radicular pain: a pathway for care developed by the British Pain Society. Br J Anaesth 2013;111:112–20. 10.1093/bja/aet172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Macvicar J, King W, Landers MH et al. . The effectiveness of lumbar transforaminal injection of steroids: a comprehensive review with systematic analysis of the published data. Pain Med 2013;14:14–28. 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2012.01508.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Staal JB, de Bie RA, de Vet HC et al. . Injection therapy for subacute and chronic low back pain: an updated Cochrane review. Spine 2009;34:49–59. 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181909558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chou R, Hashimoto R, Friedly J et al. . Epidural corticosteroid injections for radiculopathy and spinal stenosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 2015;163:373–81. 10.7326/M15-0934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lewis RA, Williams N, Matar HE et al. . The clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of management strategies for sciatica: systematic review and economic model. Health Technol Assess 2011;15:1–578. 10.3310/hta15390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lewis RA, Williams NH, Sutton AJ et al. . Comparative clinical effectiveness of management strategies for sciatica: systematic review and network meta-analyses. Spine J 2015;15:1461–77. 10.1016/j.spinee.2013.08.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Racoosin JA, Seymour SM, Cascio L et al. . Serious neurologic events after epidural glucocorticoid injection—the FDA's risk assessment. N Engl J Med 2015;373:2299–301. 10.1056/NEJMp1511754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kainer MA, Reagan DR, Nguyen DB et al. , Tennessee Fungal Meningitis Investigation Team. Fungal infections associated with contaminated methylprednisolone in Tennessee. N Engl J Med 2012;367:2194–203. 10.1056/NEJMoa1212972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Manchikanti L, Malla Y, Wargo BW et al. . A prospective evaluation of complications of 10,000 fluoroscopically directed epidural injections. Pain Physician 2012;15:131–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Atluri S, Glaser SE, Shah RV et al. . Needle position analysis in cases of paralysis from transforaminal epidurals: Consider alternative approaches to traditional technique. Pain Physician 2013;16:321–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Specialty utilization data files from Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. http://www.cms.hhs.gov/ (accessed 22 Mar 2016).

- 46.Vandenbroucke JP, Von Elm E, Altman DG et al. , Iniciativa STROBE. Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE): Explanation and elaboration. Gac Sanit 2009;23:158 10.1016/j.gaceta.2008.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Friedly J, Chan L, Deyo R. Increases in lumbosacral injections in the Medicare population: 1994 to 2001. Spine 2007;32:1754–60. 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3180b9f96e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Friedly J, Chan L, Deyo R. Geographic variation in epidural steroid injection use in Medicare patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2008;90:1730–7. 10.2106/JBJS.G.00858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Abbott ZI, Nair KV, Allen RR et al. . Utilization characteristics of spinal interventions. Spine J 2012;12:35–43. 10.1016/j.spinee.2011.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.US Department of Health and Human Services. Office of Inspector General (OIG). Inappropriate Medicare Payments for Transforaminal Epidural Injection Services (OEI-05-09-00030). August 2010. http://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-05-09-00030.pdf (accessed 22 Mar 2016). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 51.Manchikanti L, Falco FJE, Pampati V et al. . Cost utility analysis of caudal epidural injections in the treatment of lumbar disc herniation, axial or discogenic low back pain, central spinal stenosis, and post lumbar surgery syndrome. Pain Physician 2013;16:E129–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Manchikanti L, Benyamin RM, Falco FJE et al. . Guidelines warfare over interventional techniques: is there a lack of discourse or straw man? Pain Physician 2012;15:E1–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Manchikanti L, Kaye AD, Hirsch JA. Comment RE: Chou R, Hashimoto R, Friedly J, et al. RE: Epidural corticosteroid injections for radiculopathy and spinal stenosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 2015;163:373–81. Ann Intern Med 2016;164:633 10.7326/L15-0566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Manchikanti L, Boswell MV. Appropriate design and methodologic quality assessment, clinically relevant outcomes are essential to determine the role of epidural corticosteroid injections. Commentary RE: Chou R, Hashimoto R, Friedly J, et al. Epidural corticosteroid injections for radiculopathy and spinal stenosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 2015;163:373–81. Evid Based Med; 17 February 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Eden J, Levit L, Berg A et al., eds Committee on Standards for Systematic Reviews of Comparative Effectiveness Research; Institute of Medicine. Finding what works in health care. Standards for systematic reviews. Washington: (DC: ): The National Academies Press, 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cappola AR, FitzGerald GA. Confluence, not conflict of interest: name change necessary. JAMA 2015;314:1791–2. 10.1001/jama.2015.12020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chang Chien GC, Knezevic NN, McCormick Z et al. . Transforaminal versus interlaminar approaches to epidural steroid injections: a systematic review of comparative studies for lumbosacral radicular pain. Pain Physician 2014;17:E509–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Manchikanti L, Singh V, Pampati V et al. . Comparison of the efficacy of caudal, interlaminar, and transforaminal epidural injections in managing lumbar disc herniation: Is one method superior to the other? Korean J Pain 2015;28:11–21. 10.3344/kjp.2015.28.1.11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-013042supp_appendices.pdf (1.1MB, pdf)