Abstract

Background

WHO advocates 2-hour oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) for detecting diabetes mellitus (DM). OGTT is the most sensitive method to detect DM in patients with coronary artery disease (CAD). Considered time consuming, the use of OGTT is unsatisfactory. A 1-hour plasma glucose (1hPG) test has not been evaluated as an alternative in patients with CAD.

Objectives

To create an algorithm based on glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c), fasting plasma glucose (FPG) and 1hPG limiting the need of a 2-hour plasma glucose (2hPG) in patients with CAD.

Methods

951 patients with CAD without DM underwent OGTT. A 2hPG≥11.1 mmol/L was the reference for undiagnosed DM. The yield of HbA1c, FPG and 1hPG was compared with that of 2hPG.

Results

Mean FPG was 6.2±0.9 mmol/L, and mean HbA1c 5.8±0.4%. Based on 2hPG≥11.1 mmol/L 122 patients (13%) had DM. There was no value for the combination of HbA1c and FPG to rule out or in DM (HbA1c≥6.5%; FPG≥7.0 mmol/L). In receiver operating characteristic analysis a 1hPG≥12 mmol/L balanced sensitivity and specificity for detecting DM (both=82%; positive and negative predictive values 40% and 97%). A combination of FPG<6.5 mmol/L and 1hPG<11 mmol/L excluded 99% of DM. A combination of FPG>8.0 mmol/L and 1hPG>15 mmol/L identified 100% of patients with DM.

Conclusions

Based on its satisfactory accuracy to detect DM an algorithm is proposed for screening for DM in patients with CAD decreasing the need for a 2-hour OGTT by 71%.

Keywords: Oral Glucose Tolerance Test, HbA1c, Fasting Plasma Glucose, Screening, Diabetes

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This algorithm limits the use of a full oral glucose tolerance test with maintained accuracy.

It is based on standardised examinations of a large European population with coronary artery disease.

Blood glucose was analysed with a quality controlled equipment and glycated haemoglobin in a central laboratory.

Great efforts were made to find suited populations for external validation without success, but several studies evaluated 1-hour plasma glucose in other cohorts with encouraging results.

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus (DM) has a considerable negative impact on the prognosis of patients with coronary artery disease (CAD), and its presence should alert a clinician that intensive, multifactorial treatment should be initiated to counteract this high risk.1 A meticulous use of evidence-based treatment is, due to the high cardiovascular event rate rewarding, with a substantially lower number needed to treat to avoid future cardiovascular events than in patients with CAD only.2–4 Accordingly, it is important to identify DM and even other forms of dysglycaemia such as impaired glucose tolerance in patients with CAD.1 5 6 Such patients have a high prevalence of dysglycaemic conditions. It is a concern that the presence of dysglycaemia often remains undetected without proper testing as shown more than a decade ago, but still a problem as demonstrated by the recent EUROpean Action on Secondary and Primary prevention of coronary heart disease In order to Reduce Events (EUROASPIRE IV) survey.7–9

Current international guidelines endorse the use of three methods to identify DM: fasting plasma glucose (FPG), 2-hour postload plasma glucose (2hPG) from an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) and glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c).1 10–14 A report from EUROASPIRE IV demonstrated that OGTT was the most sensitive test when screening for DM in patients with CAD while FPG in combination with HbA1c left about a fifth of patients with DM unidentified.9 A disadvantage with an OGTT is that it is time consuming in comparison with the single blood test needed for a FPG or HbA1c. Owing to this attempts to construct algorithms to limit the use of OGTT have been made. An algorithm combining FPG and HbA1c limited the use of OGTT in people with impaired fasting glucose (IFG),15 and Gholap et al16 presented an algorithm based on HbA1c in patients with acute coronary syndromes. Both these studies based their cut point on ‘pragmatic’ grounds due to limited availability of actual data.16 A 1-hour plasma glucose (1hPG) test has been suggested as a time-saving option, still retaining reasonably good accuracy in detecting type 2 DM when screening high-risk individuals in a general population.17 18 An elevated 1hPG is associated with an enhanced risk of future DM19 and cardiovascular disease.20 To the best of our knowledge, no study has evaluated the possibility to use 1hPG as a marker for DM in patients with CAD.

The aim of the present study was to investigate an algorithm based on a combination of HbA1c, FPG and 1hPG in order to limit the use of a 2hPG test without losing the accuracy of detecting DM in patients with CAD.

Research design and methods

Study population

Details of EUROASPIRE IV, conducted in 24 European countries from May 2012 to April 2013, have been presented elsewhere.9 This description relates to details of special interest for the present study. The study population comprises 951 patients (18–80 years) with stable CAD and free from diabetes in whom FPG, HbA1c, 1hPG and 2hPG were determined.

Methods

Methods for recording and definitions of educational level, current smoking, central obesity and blood pressure have been described elsewhere.9

A standard OGTT was performed in the morning after ≥10 hours fasting. Plasma glucose was analysed locally with a point-of-care technique (Glucose 201+, HemoCue, Ängelholm, Sweden). Values obtained with the HemoCue instrument were in 69% patients within 5%, in 91% patients within 10% and always within 14.3% of the ID Gas Chromatography - Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) method.21 The values were converted from whole venous blood to plasma applying the formula by Carstensen et al:22 plasma glucose=0.558+0.119×whole blood glucose, as used by the Euro Heart Survey on Diabetes and the Heart.23

HbA1c was measured at the central laboratory (Disease Risk Unit, National Institute for Health and Welfare, Helsinki, Finland) with an immunoturbidimetric International Federation Clinical Chemists (IFCC) aligned method (Abbot Architect analyser; Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, Illinois, USA) in fasting venous whole blood sampled in an EDTA tube.

Reference method

A 2hPG value ≥11.1 mmol/L (200 mg/dL) was used as the reference for newly detected DM. The diagnostic yield of HbA1c, FPG and 1hPG, alone or in combination, were compared with the outcome of the 2hPG. DM was considered present if HbA1c was ≥6.5% (52 mmol/L) or FPG≥7.0 mmol/mol (126 mg/dL) according to the international recommendations.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics (means, standard deviation (SD) and proportions) were used to present information on patient characteristics. The diagnostic performance of 1hPG as a marker of diabetes was studied by constructing the empirical receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. Each point on this curve represents a sensitivity/specificity pair corresponding to a particular 1hPG threshold. The area under the ROC curve (AUC) was calculated as a measure of how well 1hPG distinguishes between patients with, and without diabetes. The optimal threshold 1hPG was obtained according to the maximum Youden's J statistic (=sensitivity+specificity−1), a measure to find an optimal balance between sensitivity and specificity of a diagnostic test.

All statistical analyses were undertaken using SAS statistical software release V.9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA).24

Written, informed consent was obtained from each participant.

Patient involvement

This study was designed since patients with CAD frequently have glucose perturbations that although prognostically important but frequently left unrecognised. An often claimed reason is that the use of an OGTT is considered time consuming and thereby not convenient. A simple screening tool may result in improved willingness to screen and thereby be to the benefit of many patients. EUROASPIRE IV offered ideal possibilities to perform the investigations needed. Although the protocol was not developed with patients or lay people involved all participants were carefully informed of the purpose with the glucose tolerance testing. Patients with newly detected glucose perturbations were informed and asked to discuss this finding with their ordinary physician. The results of this investigation will be communicated via different channels including those suited for patients and lay people and hopefully also influence future management guidelines.

Results

Clinical and laboratory characteristics of the 951 participants are presented in table 1. Their mean age was 63.4 (SD=10·1) years and 25% were women. The mean FPG was 6.2±0·9 mmol/L (112±16 mg/dL), and the mean HbA1c was 5.8±0·4% (40 mmol/mol). A total of 122/951 (13%) patients had a 2hPG value ≥11.1 mmol/L (≥200 mg/dL) thereby fulfilling the definition of DM used in the present analyses.

Table 1.

Basic characteristics of 951 patients with CAD without diabetes in whom FPG, 1hPG and 2hPG was available

| Variable | Patient number 951 |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | |

| Mean (SD) | 63.4 (10.1) |

| <50 | 11 (102) |

| 50–59 | 25 (238) |

| 60–69 | 35 (334) |

| >70 | 29 (277) |

| Sex | |

| Women | 25 (241) |

| Men | 75 (710) |

| Low educational level | 10 (94; n=944) |

| Current smoking | 14 (131) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | |

| <25 | 19 (179) |

| ≥25 and <30 | 46 (437) |

| ≥30 | 35 (334) |

| Central obesity | 59 (546; n=930) |

| Blood pressure (SBP/DBP≥140/90 mm Hg) | 33 (311) |

| Plasma glucose (mmol/L) | |

| ≥7 | 15 (142) |

| Fasting (mean±SD) | 6.2±0.87 |

| 1 hour postload | 10.3±2.92 |

| 2 hours postload | 8.0±2.77 |

| HbA1c (%) | |

| ≥6.5 (≥48 mmol/mol) | 7 (61; n=918) |

| Mean (%±SD) | 5.8±0.44 |

| Pharmacological treatment | |

| ASA/antiplatelets | 94 (892) |

| β-blockers | 82 (778) |

| ACE-inhibitors | 60 (564) |

| AT-II receptor antagonists | 14 (136) |

| Diuretics | 24 (230) |

| Statins | 87 (818) |

| Low physical activity (IPAQ) | 64 (591; n=918) |

Values are per cent (n) if not otherwise stated. N within brackets=number of observations in case of incomplete information.

1hPG, 1-hour plasma glucose; 2hPG, 2-hour plasma glucose; ASA, acetylsalicylic acid or Aspirin; AT, Angiotensin II; BMI, body mass index; CAD, coronary artery disease; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; FPG, fasting plasma glucose; HbA1c, glycated haemoglobin; IPAQ, International Physical Activity Scale; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

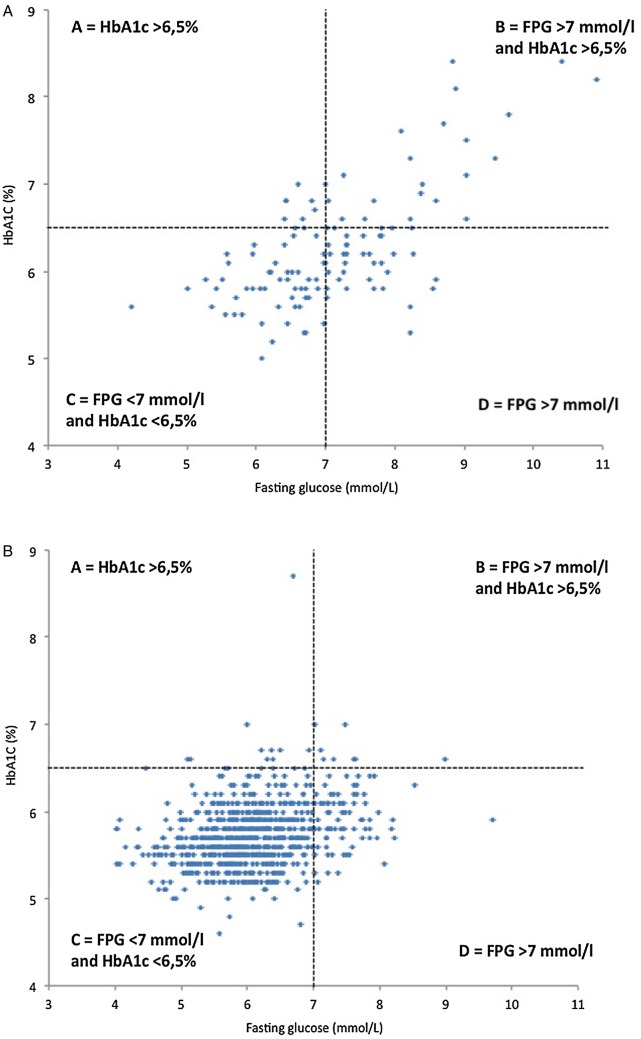

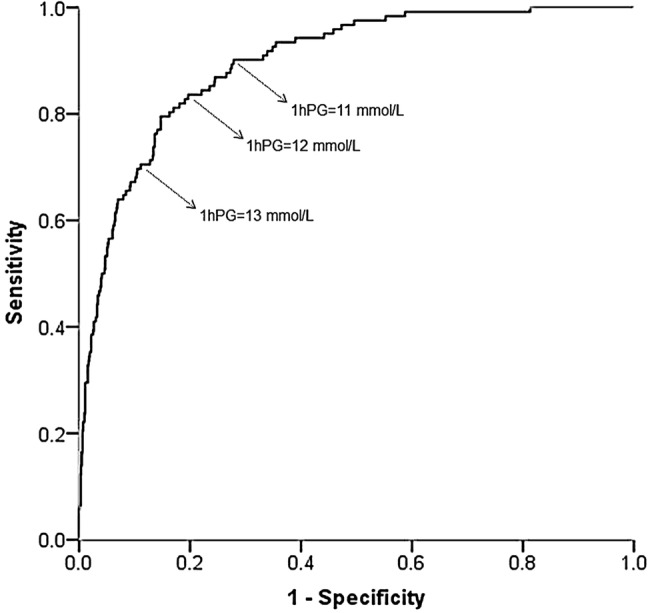

There was no clinically useful value for the combination of HbA1c and FPG to rule out or in diabetes outside the established diagnostic criteria of HbA1c≥6.5% (52 mmol/mol) or FPG≥7.0 mmol/L (126 mg/dL; figure 1). In the ROC analysis evaluating 1hPG for the diagnosis of DM (2hPG value ≥11.1 mmol/L), a 1hPG of ≥12 mmol/L was identified as the optimal balance between the sensitivity and specificity with an AUC (95% CI) of 0.90 (0.87 to 0.92). The sensitivity and specificity were both 82%, and the positive and negative predictive values were 40% and 97%, respectively (figure 2).

Figure 1.

Panel A—Patients with diabetes (2hPG≥11.1 mmol/L) who fulfil the criteria for diabetes according to (A) HbA1c≥6.5% (48 mmol/mol); (B) FPG≥7.0 mmol/L and HbA1c≥6.5%; (C) FPG<7.0 mmol/L and HbA1c<6.5%; (D) FPG≥7.0 mmol/L. Panel B—Patients free from diabetes (2hPG≤11.1 mmol/L) that have diabetes according to (A) HbA1c≥6.5%; (B) FPG≥7.0 mmol/L and HbA1c≥6.5%; (C) no test; (D) FPG≥7.0 mmol/L. Dotted lines delineate: horizontal an HbA1c level ≥6.5%; vertical a FPG≥7.0 mmol/L. 2hPG, 2-hour plasma glucose; FPG, fasting plasma glucose; HbA1c, glycated haemoglobin.

Figure 2.

In a ROC analysis evaluating 1hPG for diagnosing diabetes (defined by 2hPG value ≥11.1 mmol/L), 12 mmol/L was identified as the optimal balance between sensitivity and specificity with an AUC (95% CI) of 0.90 (0.87 to 0.92). The sensitivity and specificity were both 82%, while the positive and negative predictive values were 40% and 97%, respectively. 1hPG, 1-hour plasma glucose; 2hPG, 2-hour plasma glucose; AUC, area under the ROC curve; ROC, receiver operating characteristic.

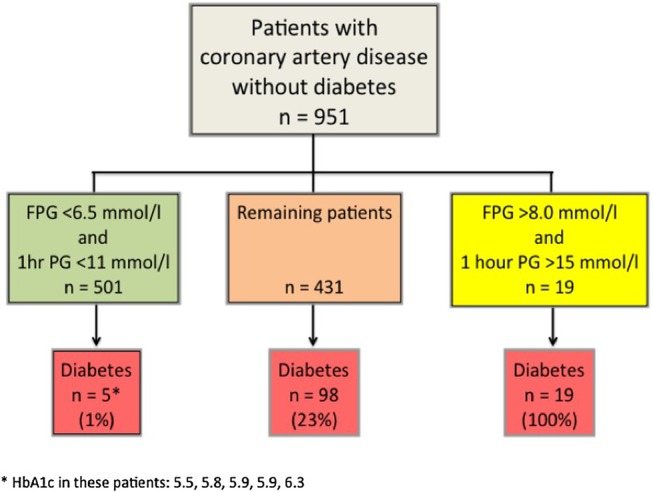

When FPG<6.5 mmol/L and 1hPG<11 mmol/L was used in combination it was possible to correctly exclude 99% of patients without DM. When FPG>8.0 mmol/L was combined with 1hPG>15 mmol/L 100% of the patients with DM were correctly identified (figure 3).

Figure 3.

The combination of FPG<6.5 mmol/L and 1hPG<11.0 mmol/L correctly excluded diabetes in 99% of patients in this category. 1hPG, 1-hour plasma glucose; FPG, fasting plasma glucose; HbA1c, glycated haemoglobin.

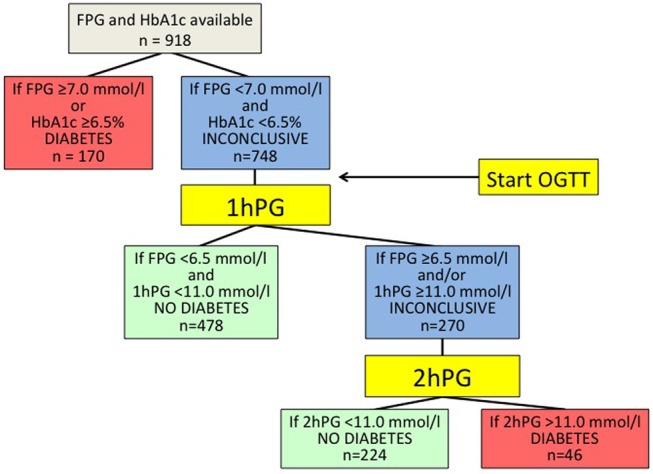

Based on these results a clinical algorithm for the identification of DM in patients with CAD is proposed that significantly limits the use of 2hPG without losing the sensitivity and specificity provided by postchallenge glucose assessment (figure 4).

Figure 4.

Proposed clinical algorithm for assessing glucometabolic status (see text for further explanation). 1hPG, 1-hour plasma glucose; 2hPG, 2-hour plasma glucose; FPG, fasting plasma glucose; HbA1c, glycated haemoglobin.

Discussion

The current practice to screen for DM by means of HbA1c and FPG in combination does not exclude DM although it may verify its presence in patients with CAD. The combined use of HbA1c, FPG and 1hPG following a standard 75 g oral glucose load did turn out as a clinically useful screening tool by means of which it was almost completely possible to exclude the presence of DM determined by 2hPG. Therefore, it is proposed that this time-saving algorithm should be applied to either detect or exclude DM with appropriate clinical accuracy in patients with CAD.

DM is a serious condition that can cause serious microvascular complications in addition to macrovascular disease if not managed well.1 The presence of DM requires effective control of risk factors such as blood pressure, blood lipids and hyperglycaemia and should therefore alert the responsible clinician to take stringent actions to reach guideline targets in risk factor management.2–4

A combination of different tests has been proposed to identify individuals with diabetes, or at high risk of developing diabetes, at a population level.17 25 These studies did not include a population of patients with verified CAD. The recent report from EUROASPIRE IV demonstrated that screening coronary patients with HbA1c, and FPG alone left one in five patients with undetected DM.9 Yet, this combination alone has been advocated as sufficient for diagnosing DM in patients with CAD.26 27 In contrast, the American Diabetes Association (ADA) in their 2016 recommendations for classification and diagnosis of DM do not prioritise HbA1c as the sole diagnostic tool and recommends an OGTT. ADA states that even if HbA1c has several advantages compared with the FPG and OGTT, these advantages may be offset by its ‘lower sensitivity at the designated cut point, greater cost and limited availability of testing in certain regions’ and, in addition that ‘numerous studies have confirmed that, compared with FPG cut points and HbA1c, the 2hPG value diagnoses more people with diabetes’.28

The combination of HbA1c and FPG did correctly identify 83% of the patients with previously undiagnosed DM in EUROASPIRE IV.9 Considering the practicality of this combination, it was applied as a first step in the presently proposed clinical algorithm for detecting DM in patients with CAD (figure 4). The use of the 1hPG in the algorithm made it possible to exclude DM with a high specificity. It halved the total time for the OGTT for about two-thirds of the patients. If the combination of FPG, HbA1c and 1hPG is inconclusive, the recommendation is to measure a 2hPG, which will identify the remaining cases of DM. Applying the proposed algorithm means that 19% of patients with CAD will only need investigation with FPG, and HbA1c, 81% will need a 1hPG, and only 29% will require a 2hPG saving time and resources. The use of the suggested algorithm requires immediate access to the glucose values by means of a point-of-care device with high accuracy such as the HemoCue.21 In screening for undiagnosed DM, the use of validated point-of-care glucose analysers are useful, since it is possible to decide after each step whether there is a need for further glucose testing. In addition, it is possible to institute proper clinical management of patients with CAD diagnosed with DM in order to reduce the risk of microvascular and macrovascular disease. It could also be potentially used in patients with cerebrovascular and peripheral artery disease who have a similar prevalence of diabetes as in the present CAD population.29

This algorithm also identifies patients with IFG but, apart from the minority of patients requiring a 2hPG, does not detect impaired glucose tolerance. It was indeed impossible to define a 1hPG that identified such individuals. Patients with impaired glucose tolerance are more likely to develop cardiovascular events than those with IFG, and the equivalent prognostic information derived by means of HbA1c is limited.30 31 In addition, HbA1c between 39 and 47 mmol/mol (5.7–6.4%) is less sensitive than IFG or impaired glucose tolerance to detect individuals with β-cell dysfunction, and insulin resistance.32

Strengths and limitations

A main strength of EUROASPIRE IV is that data are based on interviews and standardised examinations rather than data from medical records in a large cross-sectional European population of well-characterised individuals with CAD. All four tests FPG, 1hPG, 2hPG and HbA1c were collected at the same time. Standardised central training was given to the staff performing the blood sampling, and glucose measurements. All centres used the HemoCue 201+ equipment for glucose determination with appropriate quality control. HbA1c was determined in a central laboratory. The use of OGTT as the gold standard for diagnosing DM has been criticised besides from being time consuming also for reproducibility.33 In the current population it does, however, provide accurate information during a time period of at least 1 year.34

An important limitation is that the algorithm has not yet been validated in another population with CAD. On the other hand, several other studies evaluated the usefulness of 1hPG as a diagnostic tool of diabetes or predictor of future development of diabetes in other populations with encouraging results.17–20 Efforts were indeed made to find a suited population for external validation, that is, of patients with CAD and FPG, 1hPG, 2hPG and HbA1c available, but no such population could be identified. The algorithm will, however, be tested in the coming EUROASPIRE V survey planned to start during 2016. For logistical reasons, FPG, 2hPG and HbA1c were only measured once. According to present recommendations, one positive test is not sufficient to firmly establish the diagnosis of DM, which should be based on at least two separate measurements. The present algorithm based on one blood test could be further refined with a second independent blood test. This study was performed on a European population and needs to be studied in other ethnic groups before it can be accepted as generally applicable

Conclusion

A time-saving and resource-saving algorithm for screening for DM in a population of patients with CAD is proposed. It will decrease the need for a full 2-hour long OGTT to 29% of the population with satisfactory clinical accuracy. From a clinical perspective, the application of the new algorithm will leave about 1% of patients with DM undetected but this is considerably better than the much larger proportion left undetected without an OGTT.

Footnotes

Contributors: VG, LR and DDB were involved in study concept and design. All authors were involved in acquisition, analysis, interpretation of data and approval for submission, and critical revision of the manuscript. VG, LR, JT and OS were involved in drafting of the manuscript. DDB was involved in statistical analysis.

Funding: EUROASPIRE IV survey was carried out under the auspices of the EURObservational Research Programme of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). This part of the EUROASPIRE IV survey did also receive support from the Swedish Heart-Lung Foundation. The survey was supported through unrestricted research grants to the ESC from Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, GlaxoSmithKline, F Hoffman-La Roche, and Merck Sharp & Dohme. The equipment for glucose measurement was provided free of charge by the HemoCue Company, Ängelholm, Sweden.

Competing interests: VG reports grants from the Swedish Heart-Lung Foundation and a lecture honorarium from MSD Sweden and Astra Zeneca Sweden. KK reports grants from European Society of Cardiology and travel grants from Hoffman La Roche and Boehringer Ingelheim outside the submitted work. JT reports grants and fees from AstraZeneca, grants and fees from Bayer Pharma, grants from Boehringer Ingelheim, fees from Eli Lilly, fees from Impeto Medical, grants and fees from Merck Serono, grants and fees from MSD, fees from Novo Nordisk, grants and fees from Novartis, grants and fees from Sanofi-Aventis, grants from Servier and Orion pharma outside the submitted work. DW reports grants from AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb/Emea Sarl, GlaxoSmithKline, F Hoffman-La Roche, and Merck, Sharp & Dohme and fees from AstraZeneca, Merck Sharp and Dohme, Kowa Pharmaceuticals, Menarini, Zentiva, fees from Merck Sharp and Dohme outside the submitted work. LR reports grants from the Swedish Heart-Lung Foundation and the European Society of Cardiology; fees Boehringer-Ingelheim, Merck and Sanofi-Aventis, grants from Bayer outside the submitted work.

Ethics approval: The study complies with the Declaration of Helsinki, and local ethics committees of all participating centres approved EUROASPIRE IV.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Authors/Task Force M, Rydén L, Grant PJ et al. ESC guidelines on diabetes, pre-diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases developed in collaboration with the EASD: the Task Force on diabetes, pre-diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and developed in collaboration with the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Eur Heart J 2013;34:3035–87. 10.1093/eurheartj/eht108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anselmino M, Malmberg K, Ohrvik J et al. Euro Heart Survey I. Evidence-based medication and revascularization: powerful tools in the management of patients with diabetes and coronary artery disease: a report from the Euro Heart Survey on diabetes and the heart. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil 2008;15:216–23. 10.1097/HJR.0b013e3282f335d0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gaede P, Vedel P, Larsen N et al. Multifactorial intervention and cardiovascular disease in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2003;348:383–93. 10.1056/NEJMoa021778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eeg-Olofsson K, Zethelius B, Gudbjornsdottir S et al. Considerably decreased risk of cardiovascular disease with combined reductions in HbA1c, blood pressure and blood lipids in type 2 diabetes: report from the Swedish National Diabetes Register. Diab Vasc Dis Res 2016;13:268–77. 10.1177/1479164116637311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ritsinger V, Tanoglidi E, Malmberg K et al. Sustained prognostic implications of newly detected glucose abnormalities in patients with acute myocardial infarction: long-term follow-up of the Glucose Tolerance in Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction cohort. Diab Vasc Dis Res 2015;12:23–32. 10.1177/1479164114551746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.George A, Bhatia RT, Buchanan GL et al. Impaired glucose tolerance or newly diagnosed diabetes mellitus diagnosed during admission adversely affects prognosis after myocardial infarction: an observational study. PLoS ONE 2015;10:e0142045 10.1371/journal.pone.0142045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bartnik M, Rydén L, Ferrari R et al. The prevalence of abnormal glucose regulation in patients with coronary artery disease across Europe. The Euro Heart Survey on diabetes and the heart. Eur Heart J 2004;25:1880–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Norhammar A, Tenerz A, Nilsson G et al. Glucose metabolism in patients with acute myocardial infarction and no previous diagnosis of diabetes mellitus: a prospective study. Lancet 2002;359:2140–4. 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09089-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gyberg V, De Bacquer D, Kotseva K et al. Screening for dysglycaemia in patients with coronary artery disease as reflected by fasting glucose, oral glucose tolerance test, and HbA1c: a report from EUROASPIRE IV—a survey from the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J 2015;36:1171–7. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.American Diabetes Association. Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes care 2010;33(Suppl 1):S62–9. 10.2337/dc10-S062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Health Organisation (WHO) Consultation. Definition and diagnosis of diabetes and intermidiate hyperglycemia. http://www.who.int/diabetes/publications/Definition%20and%20diagnosis%20of%20diabetes_new.pdf 2006.

- 12.Gillett MJ. International Expert Committee report on the role of the A1C assay in the diagnosis of diabetes. Diabetes care 2009;32:1327–34. Clin Biochem Rev 2009;30:197–200. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Health Organization (WHO), Abbreviated report of a WHO consultation. Use of glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) in the diagnosis if diabetes mellitus. 2011. Diabetes Care 2010;33:1–25. http://www.who.int/diabetes/publications/diagnosis_diabetes2011/en/index.html 8. Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.American Diabetes A. (2) Classification and diagnosis of diabetes. Diabetes care 2015;38:S8–16. 10.2337/dc15-S005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Manley SE, Sikaris KA, Lu ZX et al. Validation of an algorithm combining haemoglobin A(1c) and fasting plasma glucose for diagnosis of diabetes mellitus in UK and Australian populations. Diabet Med 2009;26:115–21. 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2008.02652.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gholap N, Davies MJ, Mostafa SA et al. A simple strategy for screening for glucose intolerance, using glycated haemoglobin, in individuals admitted with acute coronary syndrome. Diabet Med 2012;29:838–43. 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2012.03643.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alyass A, Almgren P, Akerlund M et al. Modelling of OGTT curve identifies 1 h plasma glucose level as a strong predictor of incident type 2 diabetes: results from two prospective cohorts. Diabetologia 2015;58:87–97. 10.1007/s00125-014-3390-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abdul-Ghani MA, Lyssenko V, Tuomi T et al. The shape of plasma glucose concentration curve during OGTT predicts future risk of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2010;26:280–6. 10.1002/dmrr.1084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fiorentino TV, Marini MA, Andreozzi F et al. One-hour postload hyperglycemia is a stronger predictor of type 2 diabetes than impaired fasting glucose. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2015;100:3744–51. 10.1210/jc.2015-2573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tanaka K, Kanazawa I, Yamaguchi T et al. One-hour post-load hyperglycemia by 75g oral glucose tolerance test as a novel risk factor of atherosclerosis. Endocr J 2014;61:329–34. 10.1507/endocrj.EJ13-0370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hannestad U, Lundblad A. Accurate and precise isotope dilution mass spectrometry method for determining glucose in whole blood. Clin Chem 1997;43:794–800. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carstensen B, Lindström J, Sundvall J et al. Measurement of blood glucose: comparison between different types of specimens. Ann Clin Biochem 2008;45:140–8. 10.1258/acb.2007.006212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anselmino M, Bartnik M, Malmberg K et al. Management of coronary artery disease in patients with and without diabetes mellitus. Acute management reasonable but secondary prevention unacceptably poor: a report from the Euro Heart Survey on Diabetes and the Heart. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil 2007;14:28–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kotseva K, Wood D, De Bacquer D et al. EUROASPIRE IV: a European Society of Cardiology survey on the lifestyle, risk factor and therapeutic management of coronary patients from 24 European countries. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2016;23:636–48. 10.1177/2047487315569401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Phillips LS, Ziemer DC, Kolm P et al. Glucose challenge test screening for prediabetes and undiagnosed diabetes. Diabetologia 2009;52:1798–807. 10.1007/s00125-009-1407-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.NICE-guidelines. Hyperglycaemia in acute coronary syndromes 2011. http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg130/resources/guidance-hyperglycaemia-in-acute-coronary-syndromes-pdf VIsited: 20150510.

- 27.Sattar N, Preiss D. Screening for diabetes in patients with cardiovascular disease: HbA1c trumps oral glucose tolerance testing. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2016;4:560–2. 10.1016/S2213-8587(16)00085-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.American Diabetes A. 2. Classification and diagnosis of diabetes. Diabetes care 2016;39(Suppl 1):S13–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johansen OE, Birkeland KI, Brustad E et al. Undiagnosed dysglycaemia and inflammation in cardiovascular disease. Eur J Clin Invest 2006;36:544–51. 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2006.01679.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sourij H, Saely CH, Schmid F et al. Post-challenge hyperglycaemia is strongly associated with future macrovascular events and total mortality in angiographied coronary patients. Eur Heart J 2010;31:1583–90. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Preiss D, Welsh P, Murray HM et al. Fasting plasma glucose in non-diabetic participants and the risk for incident cardiovascular events, diabetes, and mortality: results from WOSCOPS 15-year follow-up. Eur Heart J 2010;31:1230–6. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lorenzo C, Wagenknecht LE, Hanley AJ et al. A1C between 5.7 and 6.4% as a marker for identifying pre-diabetes, insulin sensitivity and secretion, and cardiovascular risk factors: the Insulin Resistance Atherosclerosis Study (IRAS). Diabetes care 2010;33:2104–9. 10.2337/dc10-0679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sattar N, Preiss D. HbA1c in type 2 diabetes diagnostic criteria: addressing the right questions to move the field forwards. Diabetologia 2012;55:1564–7. 10.1007/s00125-012-2510-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wallander M, Malmberg K, Norhammar A et al. Oral glucose tolerance test: a reliable tool for early detection of glucose abnormalities in patients with acute myocardial infarction in clinical practice: a report on repeated oral glucose tolerance tests from the GAMI study. Diabetes care 2008;31:36–8. 10.2337/dc07-1552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]