Abstract

Objectives

To determine the prevalence and quality of antipsychotic prescribing for people with intellectual disability (ID).

Design

A clinical audit of prescribing practice in the context of a quality improvement programme. Practice standards for audit were derived from relevant, evidence-based guidelines, including NICE. Data were mainly collected from the clinical records, but to determine the clinical rationale for using antipsychotic medication in individual cases, prescribers could also be directly questioned.

Settings

54 mental health services in the UK, which were predominantly NHS Trusts.

Participants

Information on prescribing was collected for 5654 people with ID.

Results

Almost two-thirds (64%) of the total sample was prescribed antipsychotic medication, of whom almost half (49%) had a schizophrenia spectrum or affective disorder diagnosis, while a further third (36%) exhibited behaviours recognised by NICE as potentially legitimate targets for such treatment such as violence, aggression or self-injury. With respect to screening for potential side effects within the past year, 41% had a documented measure of body weight (range across participating services 18–100%), 32% blood pressure (0–100%) and 37% blood glucose and blood lipids (0–100%).

Conclusions

These data from mental health services across the UK suggest that antipsychotic medications are not widely used outside of licensed and/or evidence-based indications in people with ID. However, screening for side effects in those patients on continuing antipsychotic medication was inconsistent across the participating services and the possibility that a small number of these services failed to meet basic standards of care cannot be excluded.

Keywords: intellectual disability, learning disability, antipsychotic, prescribing practice, quality

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The large sample size suggests that our findings are likely to be generalisable to all patients with intellectual disability (ID) under the care of mental health services in the UK.

Data relating to the clinical rationale for prescribing antipsychotic medication were obtained from clinical records and direct discussions with prescribers; thus, we could assess the quality of prescribing practice in this respect rather than simply the quality of documentation.

The focus of the study was the quality of antipsychotic prescribing practice in this clinical population and not the broader clinical management of challenging behaviour. Thus, we did not collect data relating to the severity of challenging behaviour(s) or whether other therapeutic strategies to manage such behaviour(s) had been tried before antipsychotic medication was prescribed.

Information on physical health checks and side effect monitoring conducted in primary care would have been missed if the details of these assessments were not available in the mental health clinical records. Thus, the extent of such monitoring may be underestimated.

Our findings relate only to those people with ID under the care of mental health services and cannot be extrapolated to those whose care is delivered solely through primary care.

Introduction

When dealing with adversity, people with an intellectual disability (ID) may have less resilience and poorer coping strategies, which may manifest as ‘challenging behaviour’.1 It has been estimated that between a quarter and a third of people with ID across hospital and community samples exhibit such behaviour1–3 and the lifetime prevalence may be as high as 60%.4 Further, the prevalence of psychiatric illness in people with ID is estimated to be 8–15%.4 As the severity of ID increases, it becomes more difficult to diagnose mental illness and determining the aetiology of any behavioural disturbance is a matter for expert clinical judgement. One treatment strategy for managing such behaviour is antipsychotic medication, although the supporting evidence is limited.5–7 In 2012, concerns regarding the overuse of psychotropic medication in people with ID and the harms this may cause were highlighted in a national report prompted by a review of care at Winterbourne View hospital.8 Subsequently, NICE1 recommended that antipsychotic medication should only be considered for managing challenging behaviour in people with learning disability where other interventions have failed or the risk to the person or others is severe, for example, because of violence, aggression or self-injury. In the context of a quality improvement programme (QIP), we report here on the prevalence and quality of prescribing of psychotropic medication for people with ID who are under the care of secondary mental health services in the UK.

Methods

The Prescribing Observatory for Mental Health (POMH-UK) invited all National Health Service (NHS) mental health Trusts and other healthcare organisations in the UK to participate in an audit-based QIP focusing on the prevalence and quality of prescribing of psychotropic medication for people with ID. The methodology of this QIP has been described elsewhere.9 Clinical audits were conducted nationally in 2009, 2011 and 2015. We report here on the 2015 audit in which 54 mental health Trusts opted to participate.

Clinical practice standards for the QIP

Practice standards were initially derived from guidance by Deb et al10 11 and these proved to be consistent with practice recommendations in the NICE guidelines for the management of challenging behaviour in people with a learning disability1 and for the treatment of schizophrenia.12 These practice standards were (1) the indication for treatment with antipsychotic medication should be documented in the clinical records; (2) the continuing need for antipsychotic medication should be reviewed at least once a year; and (3) side effects of antipsychotic medication should be reviewed at least once a year, and this review should include assessment for the presence of extrapyramidal side effects (EPS), and screening for the four aspects of the metabolic syndrome: measures of blood pressure, obesity, glycaemic control and plasma lipids.

QIP sample and data collected

Initially, the QIP focused on prescribing practice in relation to antipsychotic medication as there were evidence-based sources from which standards could be derived. For the most recent of the three QIP clinical audits, in 2015, participating Trusts were asked to include a sample of people with ID, irrespective of whether they were prescribed psychotropic medication or not. The following data were collected on each eligible patient, using a bespoke, standardised data collection tool containing mandatory fields: patient identifier (a code known only to the Trust submitting data), age, gender, ethnicity, clinical severity of ID, care setting, psychiatric diagnoses,13 a diagnosis of epilepsy, details of prescribed psychotropic medication and documented evidence of medication review. With respect to those patients who were prescribed antipsychotic medication, the clinical rationales for such medication were collected along with evidence of side effect monitoring to allow performance against the audit standards to be measured. Audit data were collected from the clinical records except for the clinical reasons for prescribing antipsychotics for individual patients, which were to be obtained by discussion with the doctors/prescribers in the clinical team. Clinicians and clinical audit staff in each Trust collected the audit data; ethical approval is not required for audit-based quality improvement initiatives.

Data analysis

Data were submitted online using Formic software14 and analysed using SPSS (SPSS statistics version V.21. IBM, Chicago, Illinois, USA).

Individual Trust data sets were returned along with any data cleaning queries, thus allowing the accuracy of data entry to be checked.

Descriptive statistics were used to measure performance against the clinical practice standards in the total national audit sample and in each participating Trust. Benchmarking charts were produced to allow participating services to determine their absolute performance against the standards and their relative performance compared with other services. Each participating service received a customised report which provided an analysis of the audit results at national, Trust and within-Trust clinical team level.

A binary logistic regression was performed to examine the clinical factors associated with whether or not antipsychotic medication was prescribed. The analyses were conducted in two stages. First, a series of univariable analyses were performed to examine the associations between being prescribed or not prescribed an antipsychotic and age, gender, ethnicity, clinical care setting, ICD10 mental illness diagnostic categories and having a diagnosis of epilepsy. The second stage jointly examined associations with the outcome in a multivariable analysis. To simplify the final regression model, a backwards selection procedure was performed to retain only the statistically significant variables. This involved omitting non-significant variables, one at a time, until only the significant variables remain.

Results

Fifty-four Trusts submitted data for 5654 patients from 338 clinical teams. The median number of cases submitted per Trust was 147 (range 10–469).

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample and the association between these and being prescribed antipsychotic medication

The demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample are shown in table 1. Data were submitted for 5654 patients: 3628 (64%) were prescribed antipsychotic medication and 2080 (37%) were prescribed antidepressant medication. In the total sample, 24% were prescribed antipsychotic and antidepressant medication. The multivariable analysis suggested that there was an association between being prescribed an antipsychotic and the following variables: being older than 25 years of age, being cared for in a specialist ID inpatient setting and having a diagnosis of a psychotic spectrum disorder (ICD F20–F29), affective disorder (F30–F39), a disorder of psychological development (F80–F89) or epilepsy. The magnitude and direction of these associations are shown in table 2. In the 3628 patients who were prescribed antipsychotic medication, 3163 (87%) had received such medication for more than a year.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the total patient sample (n=5654)

| Key demographic and clinical characteristics | Total national sample, N=5654 |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 3445 (61%) |

| Ethnicity | |

| White/White British | 4590 (81%) |

| Black/Black British | 194 (3%) |

| Asian/Asian British | 273 (5%) |

| Mixed or other | 597 (10%) |

| Age | |

| Mean age in years (SD) | 41.2 (15.3) |

| Age bands (years) | |

| <16 | 44 (1%) |

| 16–25 | 1004 (18%) |

| 26–35 | 1262 (22%) |

| 36–45 | 946 (17%) |

| 46–55 | 1234 (22%) |

| 56–65 | 785 (14%) |

| 66 and over | 379 (7%) |

| Severity of intellectual disability | |

| Mild | 2973 (53%) |

| Moderate | 1531 (27%) |

| Severe | 1150 (20%) |

| Current ICD10 diagnoses* | |

| F00–F09 | 257 (5%) |

| F10–F19 | 138 (2%) |

| F20–F29 | 1005 (18%) |

| F30–F39 | 1332 (24%) |

| F40–F48 | 566 (10%) |

| F50–F59 | 29 (1%) |

| F60–F69 | 355 (6%) |

| F80–F89 | 1592 (28%) |

| F90–F98 | 378 (7%) |

| F99 | 11 (<1%) |

| Documented psychiatric diagnoses | |

| None of the above | 1376 (24%) |

| One of the above | 3061 (54%) |

| Multiple | 1217 (21%) |

| Epilepsy | |

| Diagnosis documented | 1328 (24%) |

| Clinical care setting | |

| ID community team | 4495 (80%) |

| Forensic inpatient | 458 (8%) |

| Specialist ID inpatient | 403 (7%) |

| General adult community team | 209 (4%) |

| Continuing care/rehabilitation | 66 (1%) |

| General adult acute ward | 23 (<1%) |

*ICD10 codes and diagnoses: F00–F09—organic, including symptomatic, mental disorders; F10–F19—Mental and behavioural disorders due to psychoactive substance use; F20–F29—schizophrenia, schizotypal and delusional disorders; F30–F39—mood (affective) disorders; F40–F48—neurotic, stress-related and somatoform disorders; F50–F59—behavioural syndromes associated with physiological disturbances and physical factors; F60–F69—disorders of adult personality and behaviour; F80–F89—disorders of psychological development; F90–F98—behavioural and emotional disorders with onset occurring in childhood and adolescence; F99—unspecified mental disorder.

Table 2.

Multivariable analyses of demographic and clinical variables associated with people with intellectual disability being prescribed antipsychotic medication

| Variable | Group | OR (95% CI) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 14–25 | 1 | <0.001 |

| 26–35 | 1.39 (1.16 to 1.67) | ||

| 36–45 | 1.48 (1.21 to 1.81) | ||

| 46–55 | 1.61 (1.33 to 1.95) | ||

| 56–65 | 1.76 (1.42 to 2.20) | ||

| 66 and older | 2.24 (1.69 to 2.96) | ||

| Clinical care setting | ID outpatient | 1 | 0.001 |

| ID inpatient | 1.7 (1.32 to 2.18) | ||

| General adult | 1.22 (0.87 to 1.71) | ||

| Forensic inpatient | 1.04 (0.83 to 1.31) | ||

| Continuing care inpatient | 1.17 (0.63 to 2.17) | ||

| F00–F19 | No | 1 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 0.36 (0.26 to 0.48) | ||

| F20–F29 | No | 1 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 19.2 (13.5 to 27.5) | ||

| F30–F39 | No | 1 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 1.36 (1.15 to 1.61) | ||

| F40–F48 | No | 1 | 0.05 |

| Yes | 0.81 (0.67 to 1.00) | ||

| F80–89 | No | 1 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 2.00 (1.70 to 2.37) | ||

| Any ICD10 mental illness diagnosis | Yes | 1 | <0.001 |

| No | 0.63 (0.52 to 0.75) | ||

| Epilepsy | No | 1 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 0.71 (0.62 to 0.81) |

Clinical rationale for antipsychotic treatment

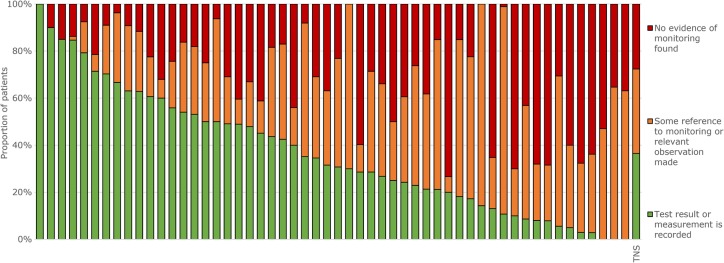

The most common reasons for prescribing the current antipsychotic medication in the total national sample were psychotic disorder (41%), general agitation and anxiety (41%), overt aggression (36%), threatening behaviour (29%), self-harm and self-injurious behaviour (19%) and obsessive behaviour (9%). Figure 1 shows the proportions of patients prescribed and not prescribed an antipsychotic and, in the former group, the proportion who had a diagnosed schizophrenia spectrum or affective disorder, exhibited a target symptom/behaviour for antipsychotic treatment recognised by NICE or neither of these clinical reasons. There were 593 (10%) patients in this latter group, in whom the most common diagnoses were disorders of psychological development (ICD10 F80–F89, which includes autism; 40%), anxiety spectrum disorders (ICD10 F40–F48; 20%) and behavioural and emotional disorders with onset usually occurring in childhood and adolescence (ICD10 F90–F98, which includes ADHD; 9%), and the most common target symptoms/behaviours prompting antipsychotic treatment were agitation (57%), psychotic symptoms (20%) and obsessive behaviours, including rituals (13%).

Figure 1.

Prevalence and nature of antipsychotic prescribing in people with intellectual disability in the total national sample (TNS).

Other medication prescribed

Thirty-seven per cent of the total national sample were prescribed antidepressant medication, 54% of whom had a diagnosis of depression or an anxiety spectrum disorder. Other diagnoses in this group of patients included disorders of psychological development (ICD10 F80–F89: 26%), schizophrenia spectrum disorders (F20–F29: 16%) and personality disorders (F60–F69: 7%).

Forty-four per cent of the sample were prescribed anticonvulsant medication (most commonly valproate, a benzodiazepine or carbamazepine), 48% of whom had a diagnosis of epilepsy. Ten per cent were prescribed anticholinergic medication.

Performance against the practice standards

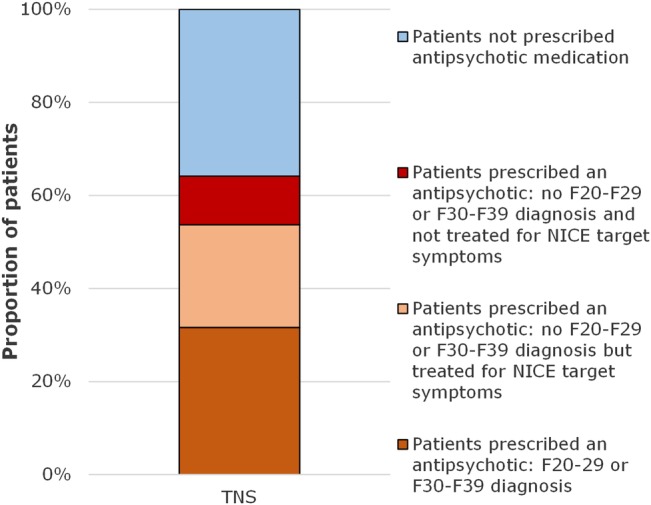

With respect to performance against the audit practice standards, (1) the clinical indication for antipsychotic medication was clear in 3537 (97%) cases; (2) of those patients who had been prescribed antipsychotic treatment for over 12 months (n=3163), 3066 (97%) had a documented medication review in the last year, and of those patients receiving drug treatments other than antipsychotics over the past 12 months (n=1334), 1191 (89%) had a documented medication review in the last year; (3) with respect to those patients who had been prescribed antipsychotic medication for more than 1 year, 1307 (41%) had a documented measure of body weight (the range across participating services was 18–100%), 1019 (32%; range 0–100%) of blood pressure, 1154 (37%; range 0–100%) of blood glucose and 1154 (37%; 0–100%) of blood lipids. In 2535 (80%; range 35–100%) of cases, there was a documented statement about side effects, and in 294 (49%; range 12–100%), there had been an assessment of potential movement disorder induced by antipsychotic medication. As an example, figure 2 shows the variation across services with respect to monitoring of glycaemic control.

Figure 2.

Proportion of people with intellectual disability prescribed antipsychotic medication for more than 1 year with documented evidence in their clinical records of monitoring of glycaemic control in the last year.

Discussion

Prevalence of prescribing of antipsychotic medication and the demographic and clinical characteristics of patients who received such prescriptions

In our sample of people with ID who were in contact with UK mental health services, just under two-thirds (64%) were prescribed antipsychotic medication. This proportion is considerably higher than the primary care prevalence of 28% identified by Sheehan et al15 using data obtained via The Health Improvement Network and the 17% of patient days identified by Glover and Williams16 using primary care data obtained via the Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD). This marked difference from other UK samples may be at least partly a consequence of the greater likelihood of mental illness and/or challenging behaviour in those people with ID who are in contact with mental health services, compared with those in primary care. Indeed, over three-quarters of our sample had at least one diagnosed mental illness, compared with fewer than one in four in the primary care sample of Sheehan et al.15 There is, however, likely to be some overlap between primary and secondary care samples as many people who receive outpatient care from mental health services receive their medication from their general practitioner. The sample identified by Sheehan et al15 may, therefore, have included patients who also received outpatient care from mental health services.

Almost one-fifth of our sample had a diagnosis of a schizophrenia spectrum disorder and, compared with those who did not have such a diagnosis, this subgroup were 19 times more likely to be prescribed antipsychotic medication. We also found that those people with a diagnosis of an affective disorder or a disorder of psychological development, including autism, were more likely to be prescribed an antipsychotic, although the magnitude of the ORs, at 1.36 and 2.0, respectively, was considerably more modest. While such prescribing partly reflects the recognition of psychotic illness as an indication for antipsychotic medication in such a context, it may also reflect that evidence-based guidelines have identified a role for such medication in the management of affective disorders and that published evidence supports its use for the amelioration of some forms of behavioural disturbance in patients with autistic spectrum disorders.17

We also found an association between antipsychotic use and age, with those who were 65 years of age or older being twice as likely to be prescribed an antipsychotic as those who were 25 years of age or younger. This is consistent with the findings of Glover and Williams16 and Sheehan et al.15 The reasons for this association are unclear, but potential explanations include an age-related increase in the prevalence of challenging behaviour and/or suboptimal processes for clinical review of the medication, resulting in prescriptions being continued unnecessarily.15

Most antipsychotic medicines have the potential to lower the seizure threshold18 19 and the lower prevalence of prescribing in patients with epilepsy that we found suggests that secondary care clinicians use these medicines cautiously in this population. Antipsychotic medicines are also associated with increased morbidity and mortality in people with dementia20 and the findings of our logistic regression analyses suggest that clinicians generally avoid antipsychotics in people with ID who also have a diagnosis of dementia. In primary care, the reverse association has been reported.15

Clinical reasons for prescribing antipsychotic medication

The use of antipsychotic medicines to treat schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and depression is supported by NICE guidelines for these conditions.12 21 22 It is also common practice. Investigating psychotropic drug use in a large US sample of adults with ID, Tsiouris et al23 found that half of such medication was prescribed for the treatment of major psychiatric disorders. In addition, the NICE guideline for the management of challenging behaviour in people with a learning disability acknowledges that antipsychotic medication may be indicated where the risk to the person or others from such behaviour is severe, for example, because of violence, aggression or self-injury.1 Applying these recognised clinical indications to our sample, over four-fifths of those prescribed an antipsychotic had one or more of these diagnoses and/or challenging behaviours. Psychotic symptoms (in the absence of a documented diagnosis of psychotic illness) and obsessive behaviours (as part of autistic spectrum disorders) accounted for a third of the remainder. In a small minority of patients, antipsychotic medication was prescribed for the management of agitation. Such use may be appropriate as part of de-escalation strategies in the prevention of violence.24 The clinical rationales for prescribing antipsychotic medication in our audit sample were consistent with the findings of a previous national audit9 and these data do not support the claims that antipsychotic medications are widely used outside of licensed and evidence-based indications in people with ID,8 16 at least in those people who are in contact with mental health services.

Our findings in this patient sample under the care of mental health services contrast with those of Glover and Williams16 who reported that potentially relevant indications for antipsychotic prescriptions were recorded in only two-fifths of cases in primary care. One potential explanation for this difference is that our audit data on the clinical rationale for antipsychotic treatment were obtained on a patient-by-patient basis from prescribing clinicians, augmenting the information extracted directly from clinical records: our aim was to examine clinical practice rather than clinical documentation. Another possible explanation is that our sample of patients were more likely to be systematically assessed and to receive treatment from clinicians who were specialists in the diagnosis and management of mental health and behavioural problems in people with ID.

Quality of prescribing practice related to antipsychotic medication

In almost all patients in our sample, the reasons for prescribing antipsychotic medication were clear and the medication had been clinically reviewed within the last year. This suggests that decisions relating to the initiation of antipsychotic medication were considered and that subsequent review of the impact of this intervention on target symptoms was systematic. These findings are consistent with those of a previous large UK audit.9 However, our findings also suggest that side effect assessment was less than assiduous, with just over a third of those patients who had been prescribed antipsychotics for more than a year having measures for body weight, blood pressure, blood glucose and lipids all documented in the clinical records and fewer than 1 in 10 having a formal assessment of antipsychotic-induced movement disorder (EPS). There was marked variation in the quality of assessment of side effects across participating services and the possibility that a small number of these services failed to meet basic standards of care cannot be excluded.

The proportion of patients assessed for metabolic side effects was relatively low compared with community-based patients with schizophrenia,25 26 perhaps partly due to the additional challenges associated with phlebotomy in people with ID.

Other psychotropic medication prescribed

Over a third of patients in our sample were prescribed antidepressant medication, half of whom had a diagnosis of an affective or anxiety spectrum disorder. These diagnoses are recognised as targets for such treatment. In our sample of patients under the care of mental health services, we found the prevalence of antidepressant use to be double that identified by Glover and Williams16 in a primary care sample, but the proportion of those prescribed an antidepressant who had a relevant comorbid disorder was similar. These findings suggest that antidepressants are commonly used for indications other than mood and anxiety disorders in people with ID, and indeed, a quarter of those patients in our sample who were prescribed antidepressant medication had a diagnosed disorder of psychological development but no mood or anxiety spectrum disorder. People with autism commonly exhibit restrictive repetitive behaviours and interests that are distressing and disruptive to functioning. Clinicians' prescribing practice in this regard may have been influenced by limited published evidence supporting the effectiveness of SSRI antidepressants in ameliorating obsessive–compulsive behaviour, aggression and anxiety in adults with autism.27

We found that anticonvulsant medication, including benzodiazepines, was prescribed for more than two-fifths of patients and that half of this subgroup had a diagnosis of epilepsy. We did not collect detailed data relating to the clinical indications for this group of medicines, but given that most are licensed for a number of different indications, for example, valproate for bipolar disorder and benzodiazepines for anxiety and insomnia, and that mood and anxiety disorders were prevalent in our sample, these are the likely indications in the remainder.

Almost 1 in 10 people in our sample were prescribed anticholinergic medication, which may reflect a perceived increased vulnerability to EPS in people with ID who are prescribed antipsychotic medication. However, anticholinergic medicines have established adverse effects on cognition and it would seem prudent to minimise their use in people with ID.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements are due to the POMH-UK leads in all participating healthcare organisations and the clinicians and clinical audit staff who collected and submitted the audit data. Thanks are also due to the following members of the POMH team: Amy Lawson, Krysia Zalewska.

Footnotes

Contributors: CP, SB and TREB contributed to the conception and design of the data collection form and the acquisition and analysis of data. All five authors contributed to the drafting of the manuscript and critically revising it for important academic content. All five authors approved the final version submitted for publication and agreed to be accountable for the accuracy and/or integrity of the work.

Funding: The work of the Prescribing Observatory for Mental Health (POMH-UK) is funded solely by subscriptions from participating healthcare organisations, the vast majority of which are NHS Trusts.

Competing interests: CP has participated in a neurosciences advisory board in relation to neurodegenerative diseases for Eli Lilly. TREB has acted as a member of scientific advisory boards for Sunovion and Otsuka/Lundbeck in relation to antipsychotic medication.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Challenging behaviour and learning disabilities: prevention and interventions for people with learning disabilities whose behaviour challenges. NICE Guideline 11 (NG11) 2015. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng11 [PubMed]

- 2.Clarke DJ, Kelley S, Thinn K et al. . Psychotropic drugs and mental retardation: disabilities and the prescription of drugs for behaviour and for epilepsy in three residential settings. J Ment Deficiency Res 1990;34:385–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kiernan C, Reeves D, Alborz A. The use of anti-psychotic drugs with adults with learning disabilities and challenging behaviour. J Intellect Disabil Res 1995;39:263–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cooper SA, Smiley E, Morrison J et al. . Mental ill-health in adults with intellectual disabilities: prevalence and associated factors. Br J Psychiatry 2007;190:27–35. 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.022483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brylewski J, Duggan L. Antipsychotic medication for challenging behaviour in people with intellectual disability: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J Intellect Disabil Res 1999;43:360–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tyrer P, Oliver-Africano P, Romeo R et al. . Neuroleptics in the treatment of aggressive challenging behaviour for people with intellectual disabilities: a randomised controlled trial (NACHBID). Health Technol Assess 2009;21:1–54. 10.3310/hta13210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Matson JL, Neal D. Psychotropic medication use for challenging behaviors in persons with intellectual disabilities: an overview. Res Dev Disabil 2009;30:572–86. 10.1016/j.ridd.2008.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Department of Health. Transforming care: a national response to Winterbourne View hospital. Department of Health, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paton C, Flynn A, Shingleton-Smith A et al. . Nature and quality of antipsychotic prescribing practice in UK psychiatry of intellectual disability services. J Intellect Disabil Res 2011;55:665–74. 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2011.01421.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deb S, Clarke D, Unwin G. Using Medication to Manage Behaviour Problems among Adults with a Learning Disability. University of Birmingham, 2006. http://www.ld-medication.bham.ac.uk/ [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deb S, Kwok H, Bertelli M et al. . Guideline Development Group of the WPA Section on Psychiatry of Intellectual Disability. International guide to prescribing psychotropic medication for the management of problem behaviours in adults with intellectual disabilities. World Psychiatry 2009;8:181–6. 10.1002/j.2051-5545.2009.tb00248.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Psychosis and schizophrenia in adults: treatment and management. NICE Guideline (CG178), 2014. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg178 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.ICD-10. World Health Organisation. 2015. http://apps.who.int/classifications/icd10/browse/2015/en#/V

- 14. Formic software. http://www.formic.com/survey-software/

- 15.Sheehan R, Hassiotis A, Walters K et al. . Mental illness, challenging behaviour, and psychotropic drug prescribing in people with intellectual disability: UK population based cohort study. BMJ 2015;351:h4326 10.1136/bmj.h4326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Glover G, Williams R. Prescribing of psychotropic drugs to people with learning disabilities and/or autism by general practitioners in England. Public Health England, 2015. PHE publications gateway number:2015105. http://www.improvinghealthandlives.org.uk/securefiles/160131_1129//Psychotropic%20medication%20and%20people%20with%20learning%20disabilities%20or%20autism.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sawyer A, Lake JK, Lunsky Y et al. . Psychopharmacological treatment of challenging behavior in adults with autism and intellectual disabilities: a systematic review. Res Autism Spectr Disord 2014;8:803–13. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pisani F, Oteri G, Costa C et al. . Effects of psychotropic drugs on seizure threshold. Drug Safety 2002;25:91–110. 10.2165/00002018-200225020-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alper K, Schwartz KA, Kolts RL et al. . Seizure incidence in psychopharmacological clinical trials: an analysis of Food and Drug Administration (FDA) summary basis of approval reports. Biol Psychiatry 2007;62:345–54. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.09.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Banerjee S. The use of antipsychotic medication for people with dementia: time for action. Department of Health, 2009. http://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/pdf/Antipsychotic%20Bannerjee%20Report.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 21.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Bipolar disorder: the assessment and management of bipolar disorder in adults, children and young people in primary and secondary care. NICE Guideline (CG185), 2014. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg185 [Google Scholar]

- 22.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Depression in adults. NICE Guideline (CG90). 2009. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg178 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tsiouris JA, Kim SY, Brown WT et al. . Prevalence of psychotropic drug use in adults with intellectual disability: positive and negative findings from a large scale study. J Autism Dev Disord 2013;43:719–31. 10.1007/s10803-012-1617-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Violence and aggression: short-term management in mental health, health and community settings. NICE Guideline (NG10), 2015. http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng10 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barnes TR, Bhatti SF, Adroer R et al. . Screening for the metabolic side effects of antipsychotic medication: findings of a 6-year quality improvement programme in the UK. BMJ Open 2015;5:e007633 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-007633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Crawford MJ, Jayakumar S, Lemmey SJ et al. . Assessment and treatment of physical health problems among people with schizophrenia: national cross-sectional study. Br J Psychiatry 2014;205:473–7. 10.1192/bjp.bp.113.142521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Williams K, Brignell A, Randall M et al. . Selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors for treating people with autism spectrum disorders. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;(8):CD004677 http://www.cochrane.org/CD004677/BEHAV_selective-serotonin-reuptake-inhibitors-for-treating-people-with-autism-spectrum-disorders [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]