Abstract

Objective

To assess the prevalence and causes of visual impairment (VI) among a rural population aged 40 years and older in the state of Telangana in India.

Design

Population-based cross-sectional study.

Setting

Districts of Adilabad and Mahbubnagar in south Indian state of Telangana, India.

Participants

A sample of 6150 people was selected using cluster random sampling methodology. A team comprising a trained vision technician and a field worker visited the households and conducted the eye examination. Presenting, pinhole and aided visual acuity were assessed. Anterior segment was examined using a torchlight. Lens was examined using distant direct ophthalmoscopy in a semidark room. In all, 5881 (95.6%) participants were examined from 123 study clusters. Among those examined, 2723 (46.3%) were men, 4824 (82%) had no education, 2974 (50.6%) were from Adilabad district and 1694 (28.8%) of them were using spectacles at the time of eye examination.

Primary outcome measure

VI was defined as presenting visual acuity <6/18 in the better eye and it included moderate VI (<6/18 to 6/60) and blindness (<6/60).

Results

The age-adjusted and gender-adjusted prevalence of VI was 15.0% (95% CI 14.1% to 15.9%). On applying binary logistic regression analysis, VI was associated with older age groups. The odds of having VI were higher among women (OR 1.2; 95% CI 1.0 to 1.4). Having any education (OR 0.4; 95% CI 0.3 to 0.6) and current use of glasses (OR 0.19; 95% CI 0.1 to 0.2) were protective. VI was also higher in Mahbubnagar (OR 1.0 to 1.5) district. Cataract (54.7%) was the leading cause of VI followed by uncorrected refractive errors (38.6%).

Conclusions

VI continues to remain a challenge in rural Telangana. As over 90% of the VI is avoidable, massive eye care programmes are required to address the burden of VI in Telangana.

Keywords: PRIMARY CARE, EPIDEMIOLOGY

Strengths and limitations of this study.

A population-based study design that achieved a good response rate.

Covered two large districts of Telangana in India.

Provided insights into prevalence and causes of visual impairment that can be used for programme planning.

It was a rapid assessment survey hence posterior segment may have been underestimated.

India has a large burden of blindness and moderate and severe visual impairment (VI). It was estimated that over 8.3 million people are blind in India.1 Of the total population with moderate and severe VI worldwide, 31% of them are estimated to be in India.1 Similar to other regions, a declining trend in the prevalence of VI is reported in India.2 3 Most of the global data are derived from regional population-based surveys that were carried out in recent years, mostly using rapid assessment methods.1

The WHO's recent report on ‘Universal Eye Health: A global action plan 2014–2019’ highlights the need for regional surveys to generate evidence on the magnitude and causes of VI.4 It also recommends that the member states target 25% reduction in the prevalence of VI from 2010 baseline.4 This underscores the importance of periodic regional surveys as a mechanism to understand both the burden and the trends in the prevalence of VI over time and to plan strategies to address it.5

The state of Telangana was separated from Andhra Pradesh as the new 29th state of India in 2014. This newly formed state comprises 10 districts and has a population of 35.2 million people as per the 2011 census.6 The combined population of the two districts of Adilabad and Mahbubnagar was 6.8 million.6 Mahbubnagar is the largest district in the state and is closer to the capital Hyderabad. It has the highest proportion of rural population (85%) compared with other districts including Adilabad (72%). The overall proportion of rural population in Telangana is 69%. The literacy rate in the rural population in Mahbubnagar district (52%) is lower compared with Adilabad district (55.7%), both of which are lower than the state average.6

Like other districts in the state, healthcare facilities in general, and eye care facilities in particular are confined to large towns.7 A few non-governmental organisations provide eye care services through ‘outreach’ screening camps in Mahbubnagar district and the government run hospital at Adilabad also provides eye care including cataract surgeries. L V Prasad Eye Institute (LVPEI), a major eye care service provider based in Hyderabad has established a rural network of eye care centres in both these districts.8 In Adilabad, two secondary eye care centres (the first in 1996 and the second in 2005), followed by 19 primary eye care centres (vision centres) were established. In Mahbubnagar, a secondary centre was established in 1998 followed by the establishment of 10 primary eye care centres. In both the districts, the LVPEI rural eye care network is one of the largest eye care service providers.9

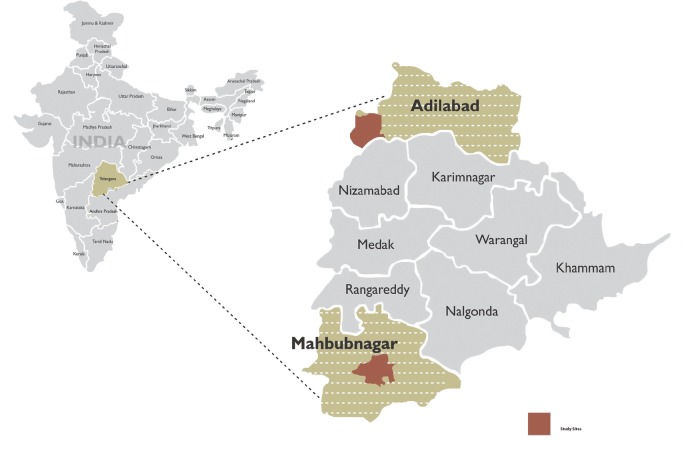

We undertook a population-based study using the Rapid Assessment of Visual Impairment (RAVI) methodology among the population aged 40 years and older in the two districts of Telangana—Adilabad and Mahbubnagar (figure 1) to assess the prevalence, causes and risk factors for VI in these districts. These two districts were also sites for population-based studies in the past. We also plan to repeat the survey in the same districts every 5–10 years to assess the trends in the prevalence of VI over time.

Figure 1.

Map showing the study areas in Adilabad and Mahbubnagar districts in the state of Telangana.

Methods

This study adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. Verbal informed consent was obtained from each participant after explaining the study procedures and before starting the eye examination.10 Permission was obtained from the head of the each village before starting the data collection. At the household level, the study procedures were explained to each individual, and oral consent was obtained in the presence of fellow family members and another individual who did not belong to the same family, or was a neighbour. Data collection for the project was carried out from February to April 2014 in Adilabad, and October to December 2014 in Mahbubnagar district.

Definitions

The Indian definitions for categories of VI were used.11 According to this blindness is defined as presenting VA worse than 6/60 in the better eye. Moderate VI (MVI) was defined as presenting VA worse than 6/18 to 6/60 in the better eye. VI is used as generic term which includes both blindness and MVI. We used the same case definitions for the causes of VI as reported in our previous studies.10 12 In short, cataract was defined as the presence of white opacity in the pupillary area on torchlight examination and/or presence of dark shadow on distance direct ophthalmoscopy in dim light causing a VI. Refractive error is defined as presence of presenting VA worse than 6/18 and improving to 6/18 or better with a pinhole. Posterior segment disease is considered as the cause of VI in cases where there was no media opacity and visual acuity (VA) did not improve with a pinhole. The causes of VI were first recorded for each eye separately and then mapped to the person. Where there was more than one cause, the condition that could be most easily corrected or treatable was considered as the cause for VI.

Sampling method

The RAVI methodology was used in this study.10 12 The sample size was calculated based on an estimated prevalence of blindness of 6%, with 20% precision, 95% CIs and a design effect of 1.5 for cluster size of 50.10 The minimum sample size needed, including an inflation of 20% to account for non-response, was 2800 participants in each district.

In total, 123 study clusters within a distance of 60 km from the two secondary centres of LVPEI in Mudhol (subdistrict) in Adilabad district and Thoodukurthy (Nagarkurnool subdistrict) in Mahbubnagar district were selected using the cluster random sampling method.10 In the first stage, study clusters were randomly selected based on population proportionate to size. In the second stage, in each of the randomly selected clusters, compact segment sampling method was used to select the households. In each cluster 50 participants aged 40 years and older were enumerated and also those available were examined by trained teams of vision technicians. The visits to the clusters were made during the time when the most of the people were likely to be available, as in early mornings and evenings. At least two attempts were made for those who were not available at first visit. The participants who were not available after multiple visits were marked as ‘non-available’ participants and were not substituted.

Eye examination

In total, three study teams, each comprising one trained vision technician and a community eye health worker, participated in the data collection. All three teams underwent rigorous training in the study procedures. A reliability study was set-up before the data collection where 40 participants were examined by the gold standard optometrist and the three vision technicians. A minimum agreement of 0.7 κ was achieved for distance and near vision testing and lens examination. After the training, the teams visited the selected households and conducted eye examinations. The detailed examination procedure is described in our previous publication.10

In short, the eye examination included demographic and ocular history, VA (unaided, pinhole and aided, if applicable) for distance and near, anterior segment examination and distant direct ophthalmoscopy. All the participants who had VI were referred to the nearest secondary centre for management and services.

VA was assessed at a distance of 6 m using a standard Snellen chart with tumbling E optotypes under ambient lighting conditions, usually in shaded outdoors. Unaided VA was recorded first, if VA was <6/12, VA assessment was repeated with a pinhole. Aided VA was recorded, if a participant reported using spectacles. The right eye was assessed first. After VA assessment, anterior segment was examined using oblique illumination with a torch light. Distant direct ophthalmoscopy was performed from a distance of 1 m under semidark conditions (indoors) to assess the media opacities such as corneal scars covering the pupil, cataract and posterior capsular opacification, if cases operated for cataract.

Data analysis

Data were initially collected on RAVI data collection forms and entered into a database created in Microsoft Access. Regular consistency checks were performed. Data analysis was performed using Stata Statistical software V.12, Chicago, Illinois, USA (StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 12. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP., 2011). Student's t-test was used to compare means and χ2 test was used to compare proportions. The prevalence estimates are presented with 95% CIs. The prevalence estimates were adjusted to the age and gender population distribution of rural Andhra Pradesh as per 2011 census.6 Indirect method of adjustment was used. The demographic associations of VI with age, gender, education, area of residence were assessed using binary logistic regression analysis. The model fit was assessed using Hosmer-Lemeshow test for goodness-of-fit.

Results

Sample characteristics

In all, 5881/6150 (95.6%) participants were examined from 123 study clusters in Adilabad and Mahbubnagar districts. Among those examined, 2723 (46.3%) were men, 4824 (82%) had no education, 2974 (50.6%) were from Adilabad district and 1694 (28.8%) of them were using spectacles at the time of eye examination. Among those not examined, 108 (40.1%) were men, 142 (52.8%) were women and data were not available for 19 (0.3%) participants. The mean age of those examined in Mahbubnagar was higher compared with those at Adilabad (53.7 vs 51.9 years; p<0.01). In Adilabad district, 47.9% of those examined were in 40–49 years age group compared with 42.9% in Mahbubnagar. Except for those in the 50–59 years age group, the proportion of participants in other age groups varied significantly in both the districts. Participation of men and women was similar in both the districts (p=0.272); however, a higher proportion of those examined were educated in Mahbubnagar district (23.6%) compared with Adilabad district (12.4; p<0.01; table 1).

Table 1.

Personal and demographic characteristics of the participants stratified by districts

| Adilabad district | Mahbubnagar district | Total | p Value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age group (years) | ||||

| 40–49 | 1424 (47.9) | 1247 (42.9) | 2671 (45.4) | <0.01 |

| 50–59 | 796 (26.8) | 732 (25.2) | 1528 (26.0) | 0.166 |

| 60–69 | 526 (17.7) | 605 (20.8) | 1131 (19.2) | <0.01 |

| 70 and above | 228 (7.7) | 323 (11.1) | 551 (9.4) | <0.01 |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 1356 (45.6) | 1367 (47.0) | 2723 (46.3) | 0.272 |

| Female | 1618 (54.4) | 1540 (53.0) | 3158 (53.7) | |

| Education level | ||||

| No education | 2604 (87.6) | 2220 (76.4) | 4824 (82.0) | <0.01 |

| Any education | 370 (12.4) | 687 (23.6) | 1057 (18.0) | |

| Total | 2974 (100.0) | 2907 (100.0) | 5881 (100.0) | |

*Significance test comparing the proportions in Adilabad and Mahbubnagar districts.

Visual impairment

Overall, VI was present in 741 individuals. The age-adjusted and gender-adjusted prevalence of VI was 15.0% (95% CI 14.1% to 15.9%). The prevalence of VI was 16.2% (95% CI 14.9% to 17.6%) in Mahbubnagar compared with 13.7% (95% CI 12.5% to 15.0%) in Adilabad district. Both MVI and blindness were higher in Mahbubnagar district compared with Adilabad but the difference was not statistically significant (table 2). Based on WHO definition, the prevalence of blindness defined as presenting VA worse than 3/60 in the better eye was 1.7% (95% CI 1.4% to 2.1%).

Table 2.

Age-adjusted and gender-adjusted prevalence of VI in Adilabad and Mahbubnagar districts in Indian state of Telangana

| MVI | Blindness | All VI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prevalence (95% CI) | Prevalence (95% CI) | Prevalence (95% CI) | |

| People ≥40 years | |||

| Adilabad | 10.4 (9.3 to 11.5) | 3.3 (2.7 to 4.0) | 13.7 (12.5 to 15.0) |

| Mahbubnagar | 12.1 (10.9 to 13.3) | 4.1 (3.5 to 5.0) | 16.2 (14.9 to 17.6) |

| Both areas combined | 11.3 (10.5 to 12.1) | 3.7 (3.2 to 4.2) | 15.0 (14.1 to 15.9) |

| People ≥50 years | |||

| Adilabad | 16.6 (14.8 to 18.5) | 5.3 (4.2 to 6.5) | 21.9 (19.8 to 24.0) |

| Mahbubnagar | 18.6 (16.8 to 20.5) | 6.5 (5.4 to 7.8) | 25.1 (23.0 to 27.3) |

| Both areas combined | 17.2 (16.4 to 19.1) | 5.8 (5.0 to 6.7) | 23.5 (22.1 to 25.0) |

MVI, moderate visual impairment; VI, visual impairment.

Among the subsample of those aged 50 years and older, the age-adjusted and gender-adjusted prevalence of VI was 23.5% (95% CI 22.1% to 25.0%). It was 25.1% (95% CI 23.0% to 27.3%) in Mahbubnagar compared with 21.9% (95% CI 19.8% to 24.0%) in Adilabad district. Similar to those aged 40 years and older, both MVI and blindness were higher in Mahbubnagar compared with Adilabad; however, this was not statistically significant (table 2).

On applying binary logistic regression analysis, VI increased with increasing age. Compared with those aged 40–49 years, the odds of VI increased to 8.3 (95% CI 5.7 to 11.9) in the 50–59 years age group, 32.3 (95% CI 22.7 to 46.0) in the 60–69 years age group and 96.4 (95% CI 66.0 to 140.6) in those aged 70 years and older. The odds of having VI was higher among women (OR 1.2; 95% CI 1.0 to 1.4) compared with men though it was of borderline significance. Having any education (OR 0.4; 95% CI 0.3 to 0.6) and current use of glasses (OR 0.19; 95% CI 0.1 to 0.2) were protective. VI was also higher in Mahbubnagar (OR 1.0 to 1.5) compared with Adilabad district (table 3).

Table 3.

Effect of sociodemographic variables on prevalence of VI using binary logistic regression analysis

| Adjusted OR | 95% CI | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age group (years) | |||

| 40–49 | 1.0 | ||

| 50–59 | 8.3 | 5.8 to 12.0 | <0.01 |

| 60–69 | 32.3 | 22.7 to 46.0 | <0.01 |

| 70 and above | 96.4 | 66.1 to 140.6 | <0.01 |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 1.0 | ||

| Female | 1.2 | 1.0 to 1.4 | 0.06 |

| Education | |||

| No education | 1.0 | ||

| Any education | 0.4 | 0.3 to 0.6 | <0.01 |

| Spectacles use for distance | |||

| No | 1.0 | ||

| Yes | 0.2 | 0.1 to 0.2 | <0.01 |

| Area | |||

| Adilabad district | 1.0 | ||

| Mahbubnagar district | 1.2 | 1.0 to 1.5 | 0.02 |

VI, visual impairment.

Table 4 shows the causes of VI stratified by districts. Overall, cataract (54.7%) was the leading cause of VI followed by uncorrected refractive errors (38.6%). The causes of VI differed significantly in both the districts. The VI caused due to cataract was 59.2% in Adilabad district compared with 51.4% in Mahbubnagar (p=0.04). Similarly, VI due to refractive errors was 32.7% in Adilabad against 42.8% in Mahbubnagar (p=0.01). Other causes of VI were similar in both the regions.

Table 4.

Causes of VI stratified by district

| Adilabad (n=309) | Mahbubnagar (n=432) | Both areas combined (n=741) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Per cent | Per cent | Per cent | p Values | |

| Cataract | 59.2 | 51.4 | 54.7 | 0.04 |

| Refractive error | 32.7 | 42.8 | 38.6 | 0.01 |

| Posterior segment disorders | 5.2 | 3.2 | 4.0 | 0.19 |

| Corneal opacity | 1.9 | 0.9 | 1.3 | 0.23 |

| Cataract surgical complications | 0.3 | 1.2 | 0.8 | 0.21 |

| Phthisis or absent globe | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.74 |

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

VI, visual impairment.

Discussion

We reported the prevalence and causes of VI from two large districts in the newly formed state of Telangana in India. Telangana has witnessed few population-based studies in the last decade and half, some of which were conducted using rapid assessment survey methods. The prevalence of MVI and blindness across various rapid assessment studies carried out in the state of Telangana are shown in table 5.

Table 5.

Prevalence of VI in various rapid assessment studies in Telangana

| Study/area | Year | Sample size | Moderate VI (%) | Blindness (%) | All VI (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RACSS, Adilabad2 | 2007 | 2160 | 13.6 | 8.0 | 21.6 |

| RAVI (Warangal)10 | 2011–2012 | 1357 | 12.5 | 9.7 | 22.2 |

| RAVI (Khammam)10 | 2011–2012 | 1191 | 17.1 | 9.2 | 26.3 |

| Present study—Adilabad | 2014 | 1550 | 16.6 | 5.3 | 21.9 |

| Present study—Mahbubnagar | 2014 | 1660 | 18.6 | 6.5 | 25.1 |

RACSS, Rapid Assessment of Cataract Surgical Services; RAVI, Rapid Assessment of Visual Impairment; VI, visual impairment.

The overall prevalence of VI found in the present study were comparable with the earlier studies in Warangal and Khammam districts; however, the proportion of MVI and blindness, which by definition sum up to the given VI, differed.10 In the present study, the prevalence of MVI and blindness were 11.3% and 3.7%, respectively, whereas the corresponding prevalence of MVI and blindness in the previous study was 8.5% and 5.1%, respectively.10 While the prevalence of MVI was higher, the prevalence of blindness was lower.

These differences in the contribution of MVI and blindness towards VI can be attributed to differences in demographic profiles, availability and accessibility of services across the districts. We also found differences in the prevalence of VI in Adilabad and Mahbubnagar districts, again suggesting a difference in availability and uptake of services. Other sociodemographic factors may also be influencing this. For example, high levels of migration were found in Mahbubnagar compared with Adilabad district.13 Also the proportion of rural population is higher in Mahbubnagar compared with Adilabad district. A higher prevalence of MVI and lower prevalence of blindness may also reflect an early trend where people with more severe levels of VI (blindness) are using the services more than that in the past. This trend may also be attributed to the availability of good quality services in the form of secondary centres and vision centres in the vicinity as these are the largest service providers in the region.6

The nationwide survey conducted in 2008 in India that found the prevalence of blindness and moderate VI as 8% and 16.8%, respectively.3 Another study from two districts in Telangana found 9.5% blindness and 14.7% moderate VI.10 Both those studies included only those who were aged 50 years and older. In the same age group (≥50 years), we found blindness and moderate VI at 5.8% and 17.2%, respectively. There seem to be a large variation in the prevalence of VI across the country and also within the districts in the state of Telangana as noted in the preceding discussion.10

It is well known that the prevalence of VI is higher in the older age groups and we had similar findings in our study.14 The association between gender and VI varied across studies in India. In our study, the association between gender and VI were of borderline significance. Earlier studies found a significantly higher proportion of VI among women.3 14 15 Another recent study from the same state reported a similar prevalence of VI among both the genders.10 The varied association can be attributed to issues related to access and uptake of services among women in the state of Telangana. There is some evidence for this from other studies where usage of eye care services is reported. The studies on barriers have shown a decline in the proportion of people who reported accessibility as a barrier for the uptake of eye care services in Andhra Pradesh.16 Studies have also reported a higher prevalence of spectacles among rural women compared with men, suggestive of higher uptake of services.17

In many community settings, literacy can be considered as a surrogate measure for the socioeconomic status of an individual. We found that those who were educated had lower odds of having VI. It is possible that those who were educated had better awareness, affordability and access to eye care services compared with their uneducated counterparts.16 This can also partly be attributed to higher visual demands among those who were educated. It also may be due to varying levels of perception of ‘felt need’ among those with and without any education. We found that those who were using spectacles at the time of examination were less likely to have VI which was an expected finding.

A majority of the VI in Telangana is avoidable. Cataract and refractive errors continue to remain the leading causes of VI in the region though there are regional variations in the proportion of VI caused due to these two conditions.10 Together, cataract and refractive errors contribute to over 90% of the total VI. From the planning of eye care services perspective, 9 out of every 10 people with VI may benefit from either cataract surgery and/or spectacles in rural Telangana, both of which can be addressed through primary and secondary eye care. If these two levels of care are integrated and provide services of high quality, most of blindness and VI can be eliminated in rural Telangana. A recent report by the World Bank has identified cataract surgery as one of the essential surgeries which is cost-effective and feasible for implementation with a significant impact on an individual.18

Among the various rapid assessment study methods used, Rapid Assessment of Avoidable Blindness (RAAB) is most commonly used method. However, RAAB examination mandates an ophthalmologist to conducted fundus examination with a direct ophthalmoscope in cases of VI, availability of an ophthalmologist in the field can be hurdle in certain situations. Moreover, RAAB provides very limited information on spectacle use, spectacle provider and spectacle coverage which are important indicators for primary eye care models such as vision centres. We used the RAVI methodology as it can provide vital indicators on primary eye care programmes; it is faster and less expensive than RAAB. The sampling methodology in RAAB and RAVI are similar.

A large randomly selected representative sample and a high response rate are the strengths of this study which provides decent external validity to the findings of this study. Extrapolating the data from this study to the 6.8 million people in the two districts of Mahbubnagar and Adilabad, there could be at least 300 000 people with VI among those aged 40 years and older, of whom 270 000 can be helped either by providing cataract surgery or spectacles. Massive efforts are required to address this huge burden of avoidable VI.

The study protocol and the definitions used to assign causes in this study have a tendency to overestimate the prevalence of cataract and refractive errors and underestimate the prevalence of posterior segment diseases such as glaucoma and diabetic retinopathy. This holds true for all rapid assessment methods. Though the causes of VI may be prone for misclassification of causes due to the use of these definitions, the prevalence of VI in itself may not be influenced by this methodology. Despite this limitation, the data from this study can be used for planning eye care services in the region. The low cost of the surveys and the use of local resources make such studies repeatable at regular intervals to access the changing trends in burden of VI over time.

In conclusion, VI continues to remain a challenge in Adilabad and Mahbubnagar districts in the newly formed state of Telangana, most of which can be addressed by cataract surgery and spectacles. A multipronged approach that can provide quality eye care in rural Telangana and also remain affordable and accessible is needed to comprehensively address this challenge of VI in the state of Telangana.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the volunteers for their participation in the study. The authors acknowledge the assistance of Rajesh Challa (vision technician) in data collection, and thank D Sandeep Rao and Devichander Chowdry for their logistic support for the study. Professor Jill Keeffe is acknowledged for her scientific inputs on the earlier versions of the manuscript. The authors also thank Dr Sreedevi Yadavalli for her language inputs on earlier versions of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Contributors: SM conceived the idea, designed and conducted the study, analysed the data and wrote the manuscript. EK assisted in data collection and supervised the field activities. RCK and GNR reviewed the earlier version of the manuscripts and provide the intellectual inputs.

Funding: This work was supported by Hyderabad Eye Research Foundation, India and Christoffel Blindenmission (CBM), Germany.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Hyderabad Eye Research Foundation, L V Prasad Eye Institute, Hyderabad, India, approved the study protocol.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Stevens GA, White RA, Flaxman SR et al. Global prevalence of vision impairment and blindness: magnitude and temporal trends, 1990–2010. Ophthalmology 2013;120:2377–84. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.05.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khanna RC, Marmamula S, Krishnaiah S et al. Changing trends in the prevalence of blindness and visual impairment in a rural district of India: systematic observations over a decade. Indian J Ophthalmol 2012;60:492–7. 10.4103/0301-4738.100560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Neena J, Rachel J, Praveen V et al. Rapid assessment of avoidable blindness in India. PLoS ONE 2008;3:e2867 10.1371/journal.pone.0002867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.WHO. Universal eye health: a global action plan 2014–2019. 2013:28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dandona L. Blindness control in India: beyond anachronism. Lancet 2000;356(Suppl):s25 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)92011-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Census. Registrar General and Census Commissioner, Census of India 2011. New Delhi: Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thomas R, Paul P, Rao GN et al. Present status of eye care in India. Surv Ophthalmol 2005;50:85–101. 10.1016/j.survophthal.2004.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rao GN, Khanna RC, Athota SM et al. Integrated model of primary and secondary eye care for underserved rural areas: the L V Prasad Eye Institute experience. Indian J Ophthalmol 2012;60:396–400. 10.4103/0301-4738.100533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rao GN. The Barrie Jones Lecture-Eye care for the neglected population: challenges and solutions. Eye (Lond) 2015;29:30–45. 10.1038/eye.2014.239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marmamula S, Narsaiah S, Shekhar K et al. Visual impairment in the South Indian State of Andhra Pradesh: Andhra Pradesh—Rapid Assessment of Visual Impairment (AP-RAVI) Project. PLoS ONE 2013;8:e70120 10.1371/journal.pone.0070120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bhaduri G. National Programme for Control of Blindness—a review. Indian J Public Health 1997;41:25–30, 32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marmamula S, Madala SR, Rao GN. Rapid assessment of visual impairment (RAVI) in marine fishing communities in South India—study protocol and main findings. BMC Ophthalmol 2011;11:26 10.1186/1471-2415-11-26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khanna RC, Murthy GV, Giridhar P et al. Cataract, visual impairment and long-term mortality in a rural cohort in India: the Andhra Pradesh Eye Disease Study. PLoS ONE 2013;8:e78002 10.1371/journal.pone.0078002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dandona L, Dandona R, Srinivas M et al. Blindness in the Indian state of Andhra Pradesh. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2001;42:908–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dandona R, Dandona L, Srinivas M et al. Moderate visual impairment in India: the Andhra Pradesh Eye Disease Study. Br J Ophthalmol 2002;86:373–7. 10.1136/bjo.86.4.373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marmamula S, Khanna RC, Shekhar K et al. A population-based cross-sectional study of barriers to uptake of eye care services in South India: the Rapid Assessment of Visual Impairment (RAVI) project. BMJ Open 2014;4:e005125 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marmamula S, Khanna RC, Narsaiah S et al. Prevalence of spectacles use in Andhra Pradesh, India: rapid assessment of visual impairment project. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol 2014;42:227–34 . 10.1111/ceo.12160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Debas HT, Donkor P, Gawande A et al. Essential surgery. Disease control priorities. 3rd edn Washington DC: World Bank, 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]