Abstract

Objectives

Cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy (CAN) and abnormal circadian blood pressure (BP) rhythm are independent cardiovascular risk factors in patients with diabetes and associations between CAN, non-dipping of nocturnal BP and coronary artery disease have been demonstrated. We aimed to test if bedtime dosing (BD) versus morning dosing (MD) of the ACE inhibitor enalapril would affect the 24-hour BP profile in patients with type 1 diabetes (T1D), CAN and non-dipping.

Setting

Secondary healthcare unit in Copenhagen, Denmark.

Participants

24 normoalbuminuric patients with T1D with CAN and non-dipping were included, consisting of mixed gender and Caucasian origin. Mean±SD age, glycosylated haemoglobin and diabetes duration were 60±7 years, 7.9±0.7% (62±7 mmol/mol) and 36±11 years.

Interventions

In this randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind cross-over study, the patients were treated for 12 weeks with either MD (20 mg enalapril in the morning and placebo at bedtime) or BD (placebo in the morning and 20 mg enalapril at bedtime), followed by 12 weeks of switched treatment regimen.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Primary outcome was altered dipping of nocturnal BP. Secondary outcomes included a measurable effect on other cardiovascular risk factors than BP, including left ventricular function (LVF).

Results

Systolic BP dipping increased 2.4% (0.03–4.9%; p=0.048) with BD compared to MD of enalapril. There was no increase in mean arterial pressure dipping (2.2% (−0.1% to 4.5%; p=0.07)). No difference was found on measures of LVF (p≥0.15). No adverse events were registered during the study.

Conclusions

We demonstrated that patients with T1D with CAN and non-dipping can be treated with an ACE inhibitor at night as BD as opposed to MD increased BP dipping, thereby diminishing the abnormal BP profile. The potentially beneficial effect on long-term cardiovascular risk remains to be determined.

Trial registration number

EudraCT2012-002136-90; Post-results.

Strengths and limitations of this study.

First randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind cross-over study investigating bedtime versus morning dosing of antihypertensive medication in type 1 diabetes.

Identical appearance of tablets for placebo and enalapril secured double blinding of patients and investigators.

Immediate validation of blood pressure measurements ensured complete data sets.

Confounders were minimised due to selection of patients and cross-over design.

Owing to the limited number of patients and short duration of the study, it was difficult to demonstrate possible effects on secondary end points.

Introduction

The normal circadian blood pressure (BP) variation comprises a night-time decline in BP and heart rate (HR), a phenomenon referred to as ‘dipping’. Dipping is caused by the increased vagal tone during the night,1 and cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy (CAN) affecting the vagal nerve function may entail a smaller reduction in HR and thereby a smaller decline in BP during the night.2

Associations between CAN and non-dipping have been described in a number of studies3–5 and CAN is encumbered with considerable increased morbidity and mortality6 7 in patients with type 1 diabetes. In a recent study, we demonstrated associations between CAN and decreased circadian variability in BP, increased pulse pressure (PP) and diastolic dysfunction,8 all of which are assumed to be pathophysiological intermediates between hypertension and heart failure.9

Whereas no pharmacological treatment is available for CAN, the 24-hour BP profile may be ameliorated by nocturnal administration of antihypertensive drugs. Indeed, Hermida et al10 demonstrated reduced cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in a large open-labelled study when antihypertensive medication was prescribed at bedtime instead of in the morning in type 2 diabetes.

By analogy, bedtime administration of antihypertensive medication might restore the 24-hour BP profile and reduce morbidity and mortality in patients with diabetes with CAN.

Accordingly, in a randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind cross-over study, we tested the hypothesis that bedtime dosing (BD) of enalapril restores the 24-hour BP profile in type 1 diabetes with CAN and non-dipping. Enalapril is a first-line choice for treatment of hypertension in type 1 diabetes and the recommended standard dose is 20 mg once daily. The maximal antihypertensive effect of the drug is seen after 4–6 hours with a diminishing but still present effect after 24 hours. Thus, theoretically, the drug should be ideal for re-establishing the normal diurnal BP variation if given at bedtime.

Our primary end point was the 24-hour BP profile with specific focus on night-time BP and dipping status. Secondary end points included measurable effect on other cardiovascular risk factors than BP, including left ventricular mass (LVM).

Methods

Materials

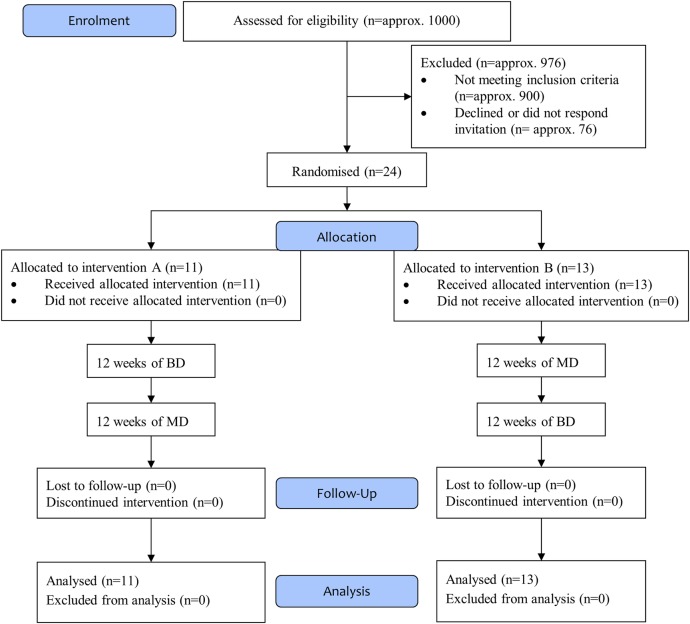

Patients were recruited between October 2012 and July 2014 from the outpatient clinic at Steno Diabetes Center or the Diabetes Unit, Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen University Hospital, Denmark. Inclusion criteria were type 1 diabetes according to the WHO/American Diabetes Association (ADA) criteria,11 age between 18 and 75 years, diabetes duration >10 years, glycosylated haemoglobin (HbA1c) below 10% (86 mmol/mol), normal urinary albumin excretion rate (<30 mg/24 hours), ECG without signs of ventricular hypertrophy, ischaemic heart disease or conduction defects, and no clinical signs or history of cardiovascular disease. Patients had to have presence of CAN defined as two or more abnormal cardiovascular autonomic function tests (see below), and reduced diurnal variation in BP defined as reduced dipping of BP of <10% during the night. Exclusion criteria were type 2 diabetes, serum creatinine >120 µmol/L, renal artery stenosis or other known kidney disease, previous myocardial infarction, coronary revascularisation, transient ischaemic attack or stroke, known side effects to or contraindications for treatment with ACE inhibitors, known or suspected abuse of alcohol or narcotics, or known cancer diagnoses. From the combined cohort of the two clinics, ∼1000 patients with type 1 diabetes were screened for autonomic neuropathy. Approximately 900 did not meet the inclusion criteria. Of the remaining ∼100 patients, 24 were included (figure 1).

Figure 1.

CONSORT flow diagram. (A) Twelve weeks of enalapril at bedtime and placebo in the morning (BD) followed by 12 weeks of placebo at bedtime and enalapril in the morning (MD). (B) Twelve weeks of MD followed by 12 weeks of BD. BD, bedtime dosing; MD, morning dosing.

The study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki II, approved by the Danish Scientific Ethical Committee (protocol number H-4-2012-061), and registered with trial registration number EudraCT 2012-002136-90. The study was carried out under the surveillance and guidance of the Good Clinical Practice (GCP) Unit at Copenhagen University Hospital in compliance with ICH-GCP guidelines. All patients gave written informed consent to the study.

Trial design: This study was an investigator-initiated, prospective, randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blinded, two-way cross-over study of 24 weeks duration investigating the effect of enalapril 20 mg given at bedtime or in the morning on diurnal BP. A detailed description of the study design has previously been published.12

In short, patients were randomised to take enalapril 20 mg in the morning and placebo at bedtime (morning dosing, MD) or as BD (placebo in the morning and 20 mg enalapril at bedtime) for 12 weeks. The effects of enalapril on BP were not expected to last longer than 24–48 hours. Subsequently, without a washout period, patients were switched to the reverse dosing time for another 12 weeks. If patients did not receive enalapril at inclusion, they entered a 4-week run-in period during which they received a lower dose (10 mg) of ACE inhibition, ensuring tolerability, and were then randomised and entered the study. Patients already treated with ACE inhibitors or angiotensin II receptor blockers were discontinued from this treatment when the study medication was begun. Other medication was continued during the study period. During the intervention period, all participants attended seven planned visits: randomisation (week 0), weeks 6, 11, 12, 18, 23 and 24.

At weeks 0, 11 and 23, blood samples were collected and trial medication was dispensed.

At weeks 6, 11, 18 and 23, 24-hour ambulatory BP measurements (ABPM) were performed.

At the end of the two study periods, weeks 12 and 24, cardiac multidetector (MDCT) was performed.

Compliance was checked by collection of used packages at the visits during the study, adverse events were assessed and glycaemic control was evaluated.

Randomisation and blinding: The patients were randomised in blocks to start with either MD or BD of enalapril (see figure 1). The pharmacy at Rigshospitalet manufactured the tablets for placebo and 20 mg of enalapril, with identical appearances. The tablets were put in containers and two containers were handed out to the patients, one for MD and the other for evening dosing, each containing either placebo or 20 mg enalapril. The pharmacy at Rigshospitalet was in charge of randomisation; hence, both patients and investigators were blinded to the treatment.

CAN tests: The testing was performed throughout the day and patients were not instructed to be fasting or avoiding caffeine. CAN was defined as two or more abnormal autonomic function tests: HR variability (HRV) during deep breathing, Valsalva ratio, lying-to-standing test and BP response to standing.13

For determination of HRV, the patients were asked to breathe deeply at a rate of 6 breaths/min while being monitored on a (50 mm/s) 12-lead ECG. The maximum and minimum HR during each breathing cycle was measured, and the mean difference of six cycles was calculated. Abnormal values were defined as below 10 bpm.13

The lying-to-standing HR ratio was determined after at least 5 min rest in the supine position and the maximal-to-minimal HR ratio was calculated from the R-R interval measured after the 30th beat after standing up, to the R-R interval measured after the 15th beat after standing up. A ratio ≤1 was classified as abnormal.13

The Valsalva test consisted of forced exhalation into a mouthpiece with a pressure of 40 mm Hg for 15 s, and the ratio of the maximum to the minimum R-R interval during the test was calculated. The test was performed three times, and the mean value of the ratios was used. Abnormal values were ratios ≤1.10.13

Orthostatic hypotension was defined as a decrease in systolic BP (SBP) of 30 mm Hg when changing from the supine to the upright position.13

Ambulatory 24-hour BP recording:14 Measurements were performed on the non-dominant arm with a properly calibrated Blood Pressure Monitor System 90217 from Space Laboratories (Washington DC). All the monitors were calibrated according to the manufacturer's guidelines before the start of the study and then once per year by the manufacturer. Furthermore, each patient was assigned to a single BP monitor to further assure that there would be no difference in measurements in the patients because of the hardware. The SBP, diastolic BP (DBP) and HR were measured automatically every 20 min during daytime (between 7:01 and 23:00) and once every hour during night-time (between 23:01 and 7:00) for 24 consecutive hours. BP measurements were validated within 2 days after completion and measurements were not considered valid if >30% of the measurements were missing, or if a minimum of 20 measurements during daytime and 7 measurements during night-time were not obtained.14 In these cases, the 24-hour measurements were repeated immediately to ensure a sufficient number of measurements. Analyses of SBP, DBP, mean arterial pressure (MAP) and PP were performed with the dedicated software (Spacelabs Healthcare ABP 90217 report management system V.3.0.0.9). Degree of night-time BP dipping was calculated as the average daytime to night-time reduction ((daytime BP−night-time BP)/daytime BP) in SBP, DBP and MAP, expressed in percentages. Furthermore, all the raw data were extracted from the software for further analysis, making it possible to generate 24-hour BP profiles.

Laboratory measurements: Blood for laboratory measurements was collected from the antecubital vein without stasis. HbA1c was measured using a chromatographic technique (Tosoh, Tokyo, Japan). Plasma N-terminal-pro brain natriuretic peptide (Pro-BNP) was measured with a sandwich electrochemiluminescence immunoassay (Roche, Hvidovre, Denmark). S-creatinine, s-potassium, s-sodium, total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, triglycerides, troponin T (TNT) and high-sensitive C reactive protein (hsCRP) were measured with standardised clinical chemistry methods.

Multidetector CT

Examinations were performed using a 320-detector CT (Aquillon One, Toshiba Medical Systems, Japan) and analysed on dedicated software (Vitrea V.6.6, Vital Images, USA). The patients were asked not to consume caffeine starting from the evening before the scan to ensure the lowest possible HR. At the time of the scan, BP, HR and ECG measurements were obtained. Patients with HR>60 bpm were given the selective β-blocker metoprolol dosed according to weight, HR and BP. The maximum allowed radiation was 3.5 mSv.

Intravenous contrast media (Visipaque 70–110 mL) according to body weight was infused with a flow rate of 5 mL/s followed by a saline chaser (30–50 mL). Image acquisition was initiated automatically at a density threshold of 180 Hounsfield Units in the descending aorta. Detector collimation was 320×0.5 mm and 100 kV tube voltage. Images were acquired during the diastolic phase and reconstructed with appropriate filtering and slice thickness.

Image analysis

Left ventricle volume (LVV) and LVM were analysed as previously described.15 LV myocardial perfusion (LVP) at rest was estimated by the LV myocardial attenuation density ratio (MyoAD ratio) and the transmural perfusion ratio as previously described.16

Statistics

Setting power to 80%, a test level of 5% and an SD of 5 mm Hg on BP measurements, a sample size of 24 patients was estimated to be sufficient to detect a difference of 4 mm Hg between the two treatment modalities.

The results are expressed as means and SD or SEM as appropriate when values are normally distributed and as medians and IQR when the values are not normally distributed. Paired Student’s t-tests were used when the values were non-skewed; otherwise, Wilcoxon's tests for paired differences were used. A two-tailed value of p<0.05 was considered statistically significant. There were no missing data.

Since two 24-hour ABPM were obtained during each treatment period, a mean of the BP values in each treatment period was used. BP, LVV and LVM analyses were performed using SAS V.9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina), while LVP analyses were performed using R V.3.2.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Patient characteristics

Baseline clinical characteristics of the 24 patients included in the study are shown in table 1. Mean age was 60±7 (SD) years, 10 males (42%), diabetes duration of 36±11 years (SD) and HbA1c of 7.9±0.7% (62±7 (SD) mmol/mol). The majority of patients (N=17; 71%) were prescribed antihypertensive treatment prior to inclusion, most often ACE inhibition.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| N=24 | |

|---|---|

| Age, years | 59.7±6.8 |

| Male gender | 10 (42) |

| Diabetes duration, years | 36.1±11.4 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 24.5±4.0 |

| HbA1c, % (mmol/mol) | 7.9±0.7 (62.3±7.4) |

| Creatinine, µmol/L | 65.9±13.0 |

| Total cholesterol, mmol/L | 4.6±0.8 |

| LDL cholesterol, mmol/L | 2.4±0.7 |

| HDL cholesterol, mmol/L | 1.8±0.6 |

| Number of antihypertensive agents per patients prior to inclusion | |

| 0 | 7 (29.2) |

| 1 | 8 (33.3) |

| 2 | 2 (8.3) |

| 3 | 5 (20.8) |

| 4 | 1 (4.2) |

| 5 | 1 (4.2) |

| Types of antihypertensive agents prior to inclusion, N (%) | |

| ACE inhibitor | 14 (58.3) |

| Angiotensin II receptor antagonist | 3 (12.5) |

| Thiazide | 9 (37.5) |

| β-blocker | 5 (20.8) |

| Calcium antagonist | 4 (16.7) |

| Spironolactone | 1 (4.2) |

Data are mean±SD, or numbers (percentages) as appropriate.

One patient had missing values in all blood tests.

BMI, body mass index; HbA1c, glycosylated haemoglobin; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; HDL, high-density lipoprotein.

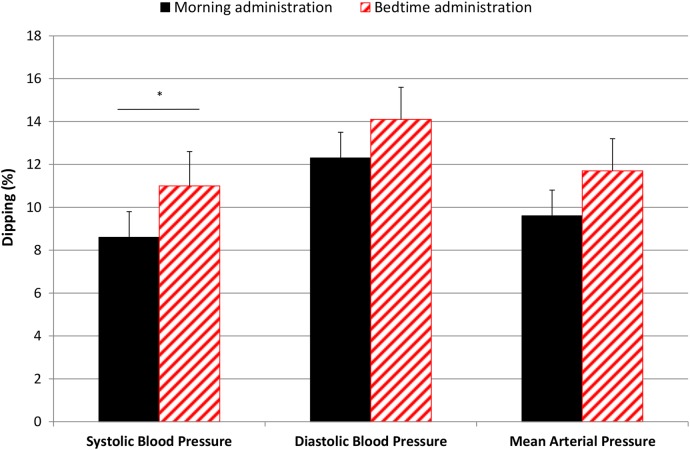

Twenty-four-hour ABPM: Results of the BP measurements are shown in table 2. Figure 2 illustrates the dipping from table 2. BD resulted in a significant increase in SBP dipping per cent (2.4 (0.03 to 4.9); p=0.048), but not significantly in MAP dipping (2.2 (−0.1 to 4.5); p=0.07), compared with MD. Accordingly, night-time SBP was reduced by 2.1 (−5.0 to 0.7) mm Hg (p=0.14) and MAP was reduced by 1.7 (−3.6 to 0.2) mm Hg (p=0.07). No significant differences were observed in daytime SBP, DBP, MAP, HR or PP during MD or BD, although an insignificant, numerical change of 1 mm Hg in SBP is noticed. There was no carry-over effect between the two treatment periods.

Table 2.

Twenty-four-hour ambulatory blood pressure

| Blood pressure (mm Hg) | MD of enalapril | BD of enalapril | Mean difference (95% CL) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Daytime SBP | 132.6±2.7 | 133.8±2.3 | 1.2 (−2.8 to 5.2) | 0.56 |

| Daytime DBP | 72.8±1.5 | 73.1±1.5 | 0.4 (−1.3 to 2.1) | 0.64 |

| Daytime MAP | 93.7±1.6 | 94.1±1.4 | 0.5 (−2.2 to 3.1) | 0.74 |

| Night-time SBP | 121.1±2.6 | 119.1±2.7 | −2.1 (−5.0 to 0.7) | 0.14 |

| Night-time DBP | 63.7±1.3 | 62.7±1.2 | −1.0 (−2.7 to 0.7) | 0.23 |

| Night-time MAP | 84.7±1.5 | 83.0±1.5 | −1.7 (−3.6 to 0.2) | 0.07 |

| Daytime PP | 59.9±1.8 | 60.8±1.8 | 0.9 (−1.5 to 3.4) | 0.46 |

| Night-time PP | 57.4±1.9 | 56.4±2.0 | −1.0 (−2.7 to 0.7) | 0.25 |

| Daytime HR | 72.0±1.6 | 73.0±1.6 | 0.9 (−0.4 to 2.1) | 0.15 |

| Night-time HR | 66.3±1.3 | 65.5±1.4 | −0.8 (2.5 to 0.9) | 0.34 |

| Dipping (%) | ||||

| SBP dipping | 8.6±1.2 | 11.0±1.6 | 2.4 (0.03 to 4.9) | 0.048a |

| DBP dipping | 12.3±1.2 | 13.9±1.5 | 1.7 (−0.7 to 4.1) | 0.17 |

| MAP dipping | 9.5±1.2 | 11.7±1.5 | 2.2 (−0.1 to 4.5) | 0.07 |

Daytime is defined as 7:01 to 23:00 and night-time as 23:01 to 7:00.

Data are mean±SEM.

SBP, DBP, MAP and PP are measured in mm Hg. Dipping is in per cent.

ap Value <0.05.

BD, bedtime dosing; CL, confidence limits; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; HR, heart rate; MAP, mean arterial pressure; MD, morning dosing; PP, pulse pressure; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

Figure 2.

Dipping (%) in blood pressure by time of enalapril administration. Black bars=morning administration, red-striped bars=bedtime administration, *p<0.05, bars illustrate means, error lines illustrate SEs.

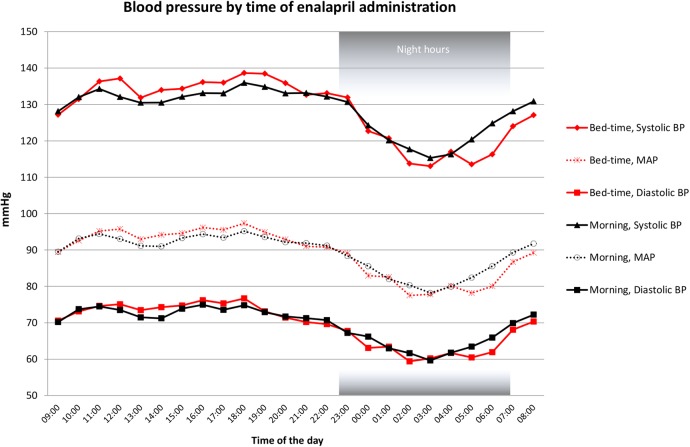

A 24-hour BP profile of mean SBP, DBP and MAP during BD and MD is shown in figure 3. As visualised, SBP and partially MAP differed between the two treatment modalities particularly between 4:00 and 8:00.

Figure 3.

Blood pressure by time of enalapril administration. Red lines=bedtime administration, black lines=morning administration. Black squares=diastolic BP at morning administration, red squares=diastolic BP at bedtime administration, transparent circle=MAP at morning administration, transparent cross=MAP at bedtime administration, rotated square=systolic BP at bedtime administration, triangle=systolic BP at morning administration. BP, blood pressure; MAP, mean arterial pressure.

LVV, LVM and LVP

Three of the 24 patients declined to undergo MDCT. We found no significant differences in LVV (p=0.15) or LVM (p=0.15) in the 21 patients studied after both treatment regimens. Neither LVP nor segmental perfusion differed between BD and MD (p>0.05 for all segments, data not shown).

Cardiac biomarkers: There were no significant differences in Pro-BNP, TNT or hsCRP, or other laboratory parameters between the two treatment regimens (p>0.05 for all parameters).

No adverse events were registered during the study.

Discussion

A statement of the principal findings: In this double-blinded, placebo-controlled, randomised cross-over study in patients with type 1 diabetes, CAN and non-dipping, we found BD of enalapril to be well tolerated without adverse effects. Our results demonstrate that it is possible to pharmacologically modify the altered diurnal BP rhythm seen in these patients.

We demonstrated an effect on BP in the late night and early morning hours, as well as increased SBP dipping when enalapril was administered at night, as suggested from the pharmacological profile of the drug. A relation between morning surge of BP and increased cardiovascular events has previously been demonstrated.17 In our study, we found no morning surge during the two treatment regimens. SBP and DBP were lower in the prewake hours as well as in the first awake hours during BD, but the morning rise in BP was similar during the two treatment regimens. Thus, from a safety point of view, our data support clinical application of BD antihypertensive treatment.

Strengths and weaknesses of the study: The primary strength of our study is the randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind cross-over design. The use of tablets with identical appearances for placebo and enalapril secured the double blinding of patients and investigators, and enabled us to monitor adherence to the treatment. Moreover, the validation of BP measurements within 2 days after completion of measurements ensured complete data sets. Thus, we interpret our results as proof of concept of positive effects on abnormal diurnal BP profile.

The weaknesses of this study are the amount of patients and length of the study. Enough patients were included for primary analysis. However, subgroup analysis was not possible due to limitations in small sample sizes when dividing our patients into smaller groups. We have previously demonstrated an association between CAN, reduced diurnal variation in BP and a non-significant increase of LVM in patients with type 1 diabetes.8 We were, however, not able to show effects on LVM or myocardial perfusion by diminishing nocturnal BP. The most likely explanation is the short duration of the study. It should be noted that the patients were not instructed to be fasting or avoid caffeine during CAN testing, although in theory it could influence the testing for CAN.

Strengths and weaknesses in relation to other studies: Most other similar studies are non-blinded with the risk of bias and only examine type 2 diabetes.10 18 This is the first study measuring dipping and BD in type 1 diabetes.

Previous studies have shown similar results on BP in type 2 diabetes.18 Qui and colleagues found that BD dosing of captopril restored the diurnal BP rhythm in a cohort of hypertensive patients with non-dipping (4 weeks intervention period, 9% diabetes).19 Thus, the effects of BD of antihypertensive medication on night-time BP have been consistent across various study populations. However, other studies find a larger effect on BP parameters. This could be due to differences in study design, as this study only changed one drug to BD. Hence, some patients were still taking other antihypertensive medication in the morning.

The meaning of the study: Autonomic neuropathy in patients with diabetes is characterised by absence of the normally occurring spontaneous fluctuations in a number of physiological parameters. Indeed, unopposed sympathetic activity at night, due to lack of vagal tone, is considered a risk factor for cardiac disease. However, CAN and diabetic nephropathy often develop in parallel, and it has been difficult to identify the relative contribution of CAN on the increased mortality and morbidity in type 1 diabetes. Therefore, we selected a subgroup of patients with type 1 diabetes and autonomic neuropathy, but without diabetic nephropathy and cardiovascular disease. Our aim was to minimise confounding by focusing on the effect of nocturnal antihypertensive treatment in patients with CAN and diminished diurnal variation in BP as their only complication to diabetes. We find that BD of enalapril can restore dipping in long-term patients with type 1 diabetes with CAN and non-dipping.

Unanswered questions and future research: The ADA20 recommends prescribing one or more antihypertensive medication at bedtime in patients with diabetes and hypertension.10 Our study suggests that it is appropriate in type 1 diabetes with CAN and non-dipping.

For future research in type 1 diabetes and non-dipping, it seems relevant to also include patients with type 1 diabetes with diabetic nephropathy in long-term studies; it is most likely that it would increase the number of patients qualified for inclusion and will make it possible to generalise future findings to also include patients with nephropathy. Furthermore, determining whether BD in type 1 diabetes has favourable long-term effects in reducing cardiovascular risk requires longer studies investigating surrogate cardiovascular disease markers or even hard end points.

Footnotes

Contributors: HØH contributed substantially to the conception and design of the study, acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data, drafted the manuscript and has approved the final version of the manuscript. TJ contributed substantially to the conception and design of the study, acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data, drafted and revised the manuscript and has approved the final version of the manuscript. UMM and PES contributed substantially to the conception and design of the study, analysis and interpretation of data, revised the manuscript and has approved the final version of the manuscript. KFK and LK contributed substantially to the conception and design of the study, interpretation of data, revised the manuscript and has approved the final version of the manuscript. KLH contributed to the design of the study, acquisition and interpretation of data, revised the manuscript and has approved the final version of the manuscript. HC contributed to the design of the study, acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data, revised the manuscript and has approved the final version of the manuscript. ST contributed to the conception and design of the study, acquisition and analysis of data, revised the manuscript and has approved the final version of the manuscript. JH contributed substantially to the conception and design of the study, analysis and interpretation of data, revised the manuscript and has approved the final version of the manuscript. HØH is the guarantor of this study; he had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication. Previous publication: Part of the data has been presented at the American Diabetes Association, 75th Annual Scientific Session 5–9th of June 2015 and at the European Association for the Study of Diabetes, 51st Annual Meeting, September 14–18 2015.

Funding: This study was supported by a grant from the Arvid Nilssons Foundation and AP Moeller Foundation.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Danish Scientific Ethical Committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Taskiran M, Rasmussen V, Rasmussen B et al. . Left ventricular dysfunction in normotensive Type 1 diabetic patients: the impact of autonomic neuropathy. Diabet Med 2004;21:524–30. 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2004.01145.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vinik AI, Ziegler D. Diabetic cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy. Circulation 2007;115:387–97. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.634949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spallone V, Maiello MR, Cicconetti E et al. . Factors determining the 24-h blood pressure profile in normotensive patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes. J Hum Hypertens 2001;15:239–46. 10.1038/sj.jhh.1001170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cardoso CRL, Leite NC, Freitas L et al. . Pattern of 24-hour ambulatory blood pressure monitoring in type 2 diabetic patients with cardiovascular dysautonomy. Hypertens Res 2008;31:865–72. 10.1291/hypres.31.865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spallone V, Bernardi L, Ricordi L et al. . Relationship between the circadian rhythms of blood pressure and sympathovagal balance in diabetic autonomic neuropathy. Diabetes 1993;42:1745–52. 10.2337/diabetes.42.12.1745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sturrock NDC, George E, Pound N et al. . Non-dipping circadian blood pressure and renal impairment are associated with increased mortality in diabetes mellitus. Diabet Med 2000;17:360–4. 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2000.00284.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boggia J, Li Y, Thijs L et al. . Prognostic accuracy of day versus night ambulatory blood pressure: a cohort study. Lancet 2007;370:1219–29. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61538-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mogensen UM, Jensen T, Køber L et al. . Cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy and subclinical cardiovascular disease in normoalbuminuric type 1 diabetic patients. Diabetes 2012;61:1822–30. 10.2337/db11-1235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Solomon SD, Janardhanan R, Verma A et al. . Effect of angiotensin receptor blockade and antihypertensive drugs on diastolic function in patients with hypertension and diastolic dysfunction: a randomised trial. Lancet 2007;369:2079–87. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60980-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hermida RC, Ayala DE, Mojón A et al. . Influence of time of day of blood pressure-lowering treatment on cardiovascular risk in hypertensive patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2011;34:1270–6. 10.2337/dc11-0297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes—2012. Diabetes Care 2012;35(Suppl 1):S11–63. 10.2337/dc12-s011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hjortkaer HØ, Jensen T, Kofoed KF et al. . Nocturnal antihypertensive treatment in patients with type 1 diabetes with autonomic neuropathy and non-dipping of blood pressure during night time: protocol for a randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind, two-way crossover study. BMJ Open 2014;4:e006142 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tesfaye S, Boulton AJM, Dyck PJ et al. . Diabetic neuropathies: update on definitions, diagnostic criteria, estimation of severity, and treatments. Diabetes Care 2010;33:2285–93. 10.2337/dc10-1303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mancia G, Fagard R, Narkiewicz K et al. . 2013 ESH/ESC guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: the Task Force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 2013;34:2159–219. 10.1093/eurheartj/eht151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fuchs A, Kühl JT, Lønborg J et al. . Automated assessment of heart chamber volumes and function in patients with previous myocardial infarction using multidetector computed tomography. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr 2012;6:325–34. 10.1016/j.jcct.2012.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Byrne C, Jensen T, Hjortkjær HØ et al. . Myocardial perfusion at rest in patients with diabetes mellitus type 1 compared with healthy controls assessed with multi detector computed tomography. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2015;107:15–22. 10.1016/j.diabres.2014.10.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li Y, Thijs L, Hansen TW et al. . Prognostic value of the morning blood pressure surge in 5645 subjects from 8 populations. Hypertension 2010;55:1040–8. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.137273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rossen NB, Knudsen ST, Fleischer J et al. . Targeting nocturnal hypertension in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Hypertension 2014;64:1080–7. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.03958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kontopoulos AG, Athyros VG, Didangelos TP et al. . Effect of chronic quinapril administration on heart rate variability in patients with diabetic autonomic neuropathy. Diabetes Care 1997;20:355–61. 10.2337/diacare.20.3.355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes—2013. Diabetes Care 2013;36(Suppl 1):S11–66. 10.2337/dc13-S011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]