Abstract

Background

Chronic psychological distress appears to have increased in recent years, mainly among the working population. The data available indicate that mental and behavioral disorders, including burnout syndrome, represent not only a personal problem for those afflicted, but also a serious public health issue. This study aimed at evaluating the effects of an outpatient burnout prevention program in a mono-center health resort setting.

Methods

Adults experiencing an above-average level of stress and thus being at an increased risk of burnout were randomized either to the intervention group (IG) or the waiting control group (WG). The 3-week program included stress management intervention, relaxation, physical exercise and moor applications. The primary outcome was change in perceived stress (PSQ) at 6 months post-intervention. Secondary outcomes included burnout symptoms, well-being, health status, psychological symptoms, back pain, and number of sick days. Participants were examined at baseline, post-intervention (3 weeks) and after 1, 3 and 6 months.

Results

Data from 88 adults (IG=43; WG=45) were available for (per protocol) analysis (mean age: 50.85; 76.1% female). Participants in the IG experienced significant immediate improvement in all outcome measures, which declined somewhat during the first three months post-intervention and then remained stable for at least another three months. Those in the WG did not experience substantial change across time. For the 109 randomized persons, results for PSQ were confirmed in an intention-to-treat analysis with missing values replaced by last observation carried forward (between-group ANCOVA for PSQ-Score at 6 months, parameter estimator for the group: –20.57; 95% CI: [-26.09; -15.04]). Large effect sizes (Cohen‘s d for PSQ: 1.09–1.72) indicate the superiority of the intervention.

Conclusions

The program proved to be effective in reducing perceived stress, emotional exhaustion and other targets. Future research should examine the long-term impact of the program and the effect of occasional refresher training.

Chronic psychological distress appears to have increased in recent years, mainly among the working population (1). The statistics of statutory pension insurance providers and health insurance providers show a rapid increase in mental health problems, such as fatigue, burnout and depression (2, 3). There is currently no general, internationally agreed definition of burnout (4, 5). According to most conceptions however, burnout is a long-term stress reaction characterized by persistent emotional exhaustion as a core symptom, cynicism/depersonalization and reduced personal accomplishment (4, 6).

Burnout is usually referred to in occupational contexts and has been described in numerous professions or groups of individuals (7– 9). Burnout is known to be associated with considerable subjective suffering and a number of physical and mental health problems (10, 11), sleep disorders (12), reduced productivity and motivation (13) and an increased risk of sick leave (14).

Due to the lack of clearly defined diagnostic and classification criteria, burnout syndrome is statistically difficult to quantify. Its actual prevalence is unknown, with cases being most likely contained within the statistics on mental and behavioural disorders (ICD-10 F00–F99) (15, 16). The numbers of incapacity-for-work cases, the number of lost work days and the number of cases of early retirement due to mental disorders in Germany have increased considerably in recent years (2). Between 2008 and 2013, the number of days off work due to mental disorders increased from 41 million (9% of total work days lost) to 79 million days (13.9%) (17, 18). The proportion of mental and behavioral disorders (ICD-10 F00–F99) leading to early retirements amounted to 24.2% in the year 2000 and had increased to 43.1% by 2014 (3).

These data indicate that mental and behavioral disorders, including the burnout syndrome, represent not just a personal problem for the individual patient, but also a serious public health issue. Given the high human and financial costs, it is important to identify chronic stress in its early stages and to prevent fully developed burnout, even if the extent of its contribution to the burden of mental illness in Germany remains unclear.

Over the past years, numerous efforts have been made to develop effective interventions aimed at reducing occupational stress and preventing burnout (7, 19– 21).

Chronic stress and burnout seem to be inseparable. There is no conceptual limitation where stress management ends and burnout prevention begins. The main focus of burnout prevention should, therefore, be on the optimization of stress-management skills (22).

As far as we know, our study is the first attempt to develop a preventive program for people at risk of burnout by combining traditional, outpatient health-resort treatments (HRT) with stress-management interventions (SMI).

Health-resort medicine (23) comprises treatment with local natural remedies, such as medical mineral waters or peloids combined as required with physical therapy interventions, exercise and relaxation therapies, among others. Outpatient preventive and rehabilitation treatments in German health resorts are approved and covered by the statutory health insurance. The length of stay at a resort is typically three weeks.

The objective of our study was to develop, implement and evaluate a 3-week program combining SMI with HRT and aiming at reducing the participants’ currently perceived stress, activating subjective resources, initiating initiating recovery processes for both body and mind and providing strategies for dealing with stressors in everyday life. We designed and conducted a prospective, randomized controlled trial (RCT) with a 6-month follow-up to study the effectiveness of the program.

Methods

Details on inclusion and exclusion criteria, intervention, sample-size estimation, and missing data handling are provided in the eBox.

The study was designed as a two-arm RCT with follow-up measurements pre- and post-intervention (T0, T1) and at 1-, 3-, and 6-months post-intervention, respectively (T2–T4).

The study population was defined as individuals with an above-average level of stress who were at increased risk for developing a burnout syndrome. Interested persons, recruited through printed and electronic advertisements, were invited to complete two screening questionnaires:

Eligible persons were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to either the intervention (IG) or waiting control group (WG) using permuted blocks of ten. The IG participated in a 3-week prevention program including SMI, relaxation techniques, physical exercise, and moor baths. The WG served as an untreated comparison for six months, before taking part in the same program.

Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was perceived stress (PSQ) at T4. The following standardized instruments were used to measure

burnout symptoms—MBI-GS-D,

well-being—World Health Organization 5-item Well-Being Index (WHO-5) (28),

health status—EuroQol (EQ-5D-5L) general health index (29) and

psychic symptoms—ICD-10-Symptom-Rating (ISR) (30).

The frequency and intensity of back pain (T0–T4) and the number of sick days during the previous six months (T0+T4) were recorded.

Data analysis

Sample size estimation revealed a minimum of 90 participants, allowing for drop outs.

Data analysis was performed for all participants who completed both the baseline assessment and at least one follow-up (per protocol (PP) analysis). For the primary outcome, in addition, an intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis was conducted. Effects were judged significant at p<0.05 (two-sided).

Baseline measurements and demographics were compared between groups using the independent samples t-test for metric and Pearson’s chi-square test for categorical variables. Changes in primary and secondary outcomes after the intervention and within the 6-month follow-up were compared between groups using t-tests or Mann-Whitney U-Tests and ANCOVA (with adjustment for baseline values). Standardized effect sizes (Cohen’s d) were calculated as the difference between two means divided by the pooled standard deviation.

Results

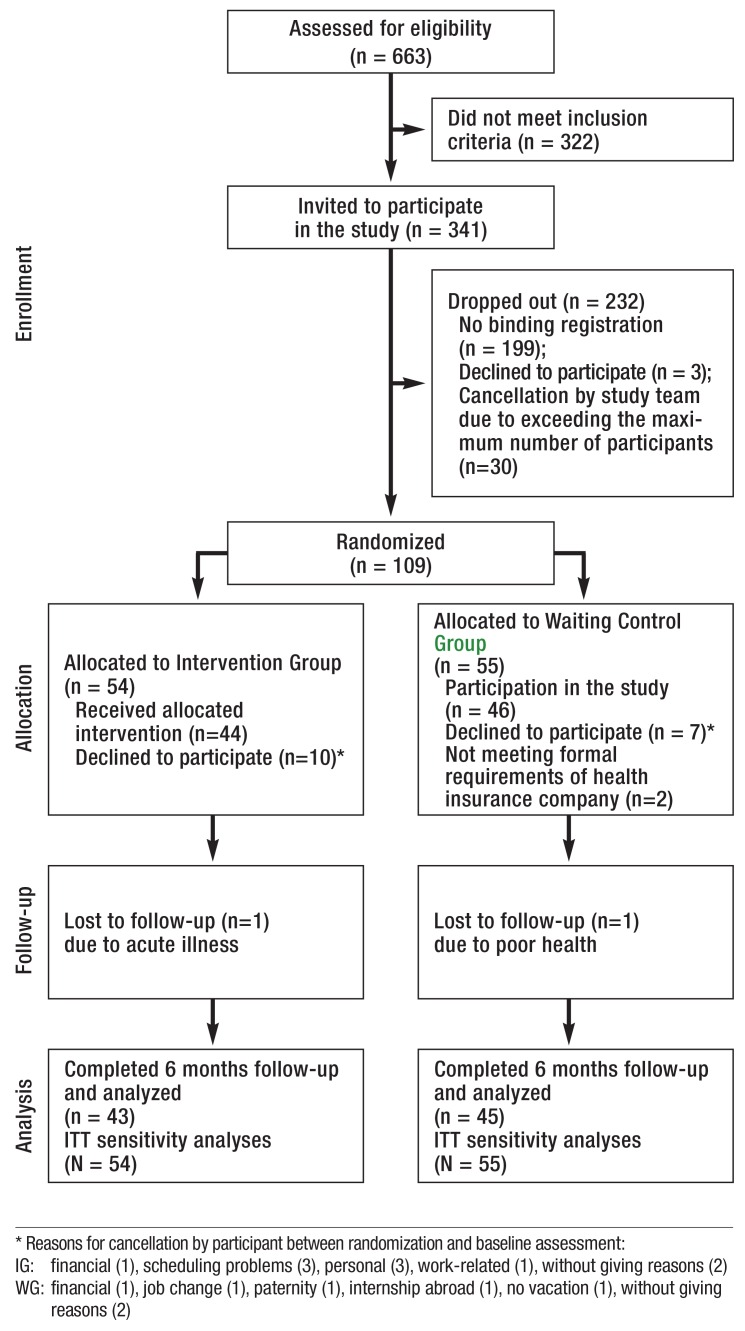

Figure 1 shows the flow of included and excluded participants throughout the study. The response rate for follow-up was 100%. Demographics and clinical variables of the final groups of participants are presented in Table 1. There were no statistically significant differences between groups at baseline in terms of demographics and outcome variables considered.

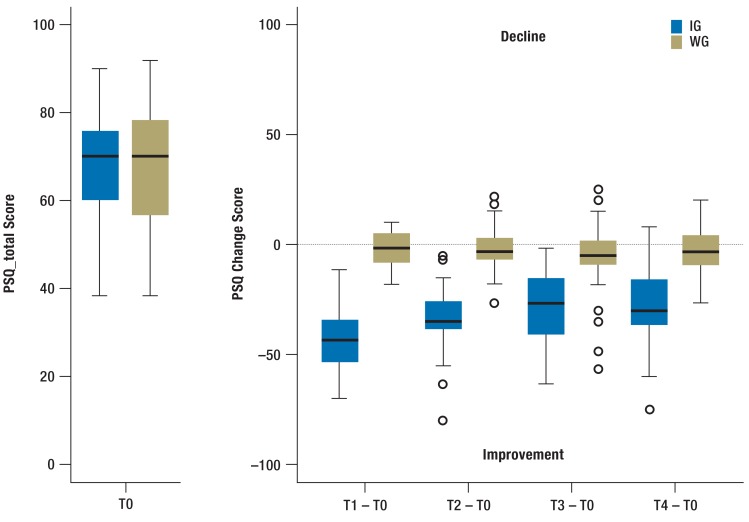

FIGURE.

Perceived stress at baseline and change score over time – IG (N=43) versus WG (N=45)

IG, intervention group; WG, waiting control group; PSQ, perceived stress questionnaire

Table 1. Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics.

|

Intervention group (n = 43) |

Waiting control group (n = 45) |

Total (n = 88) |

|

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 50.0 (7.5) | 51.6 (6.3) | 50.85 (6.9) |

| Female, n (%) | 33 (76.7%) | 34 (75.6%) | 67 (76.1%) |

|

Age groups, n (%) <50 years 50 – 59 years ≥ 60 years |

17 (39.5%) 24 (55.8%) 2 (4.7%) |

14 (31.1%) 28 (62.2%) 3 (6.7%) |

31 (35.2%) 52 (59.1%) 5 (5.7%) |

|

Marital status, n (%) married/cohabiting separated/divorced/widowed single |

28 (65.1%) 10 (23.3%) 5 (11.6%) |

28 (62.2%) 11 (24.5%) 6 (13.3%) |

56 (63.6%) 21 (23.9%) 11 (12.5%) |

|

Employment status, n (%) full-time work part-time work self-employed more than one employer other |

20 (46.5%) 9 (20.9%) 7 (16.3%) 2 (4.7%) 5 (11.6%) |

30 (66.6%) 8 (17.8%) 3 (6.7%) 4 (8.9%) 0 (0.0%) |

50 (56.8%) 17 (19.3%) 10 (11.4%) 6 (6.8%) 5 (5.7%) |

|

Highest educational level, n (%) general secondary school certificate intermediate secondary school certificate qualification for university/universities of applied sciences entrance university degree/universities of applied sciences degree |

2 (4.6%) 19 (44.2%) 7 (16.3%) 15 (34.9%) |

5 (11.0%) 16 (35.6%) 8 (17.8%) 16 (35.6%) |

7 (8.0%) 35 (39.8%) 15 (17.0%) 31 (35.2%) |

| No sick days (last 6 months), n (%) | 8 (18.6%) | 15 (33.3%) | 23 (26.1%) |

|

Number of sick days (last 6 months), mean (SD), median |

13.4 (21.4). 6.5 | 8.0 (14.7). 4 | 10.6 (18.3). 5 |

|

MBI-GS-D, mean (SD) Emotional exhaustion Cynism Professional efficacy |

4.5 (0.7) 3.5 (0.8) 3.7 (0.6) |

4.4 (0.6) 3.6 (1.1) 3.6 (0.7) |

4.4 (0.6) 3.5 (1.0) 3.7 (0.6) |

|

PSQ, mean (SD) Worries Tension Joy Demands Total |

54.4 (18.7) 77.8 (15.9) 31.0 (18.5) 73.8 (17.1) 68.8 (12.8) |

55.3 (20.5) 75.0 (15.6) 29.9 (17.7) 71.7 (18.3) 68.0 (14.0) |

54.8 (19.5) 76.4 (15.7) 30.5 (18.0) 72.7 (17.6) 68.4 (13.4) |

|

WHO-5, mean (SD) Total |

31.3 (16.1) | 30.1 (14.4) | 30.7 (15.2) |

|

EQ-5D, n (%) Mobility, no problems Self-care, no problems Usual activities, no problems Pain/discomfort, no problems Anxiety/depression, no problems |

29 (67.4%) 40 (93.0%) 19 (44.2%) 2 (4.7%) 10 (23.3%) |

29 (64.4%) 45 (100%) 16 (35.6%) 0 (0%) 10 (22.2%) |

58 (65.9%) 85 (96.6%) 35 (39.8%) 2 (2.3%) 20 (22.7%) |

|

EQ-5D, mean (SD) Health status |

59.2 (17.7) | 62.9 (14.8) | 61.1 (16.3) |

|

Back pain frequency, n (%) none/now and then periodically/often/very often or permanently |

11 (25.6%) 32 (74.4%) |

13 (28.9%) 32 (71.1%) |

24 (27.3%) 64 (72.7%) |

| Back pain severity, mean (SD) | 5.4 (2.4) | 5.6 (1.9) | 5.5 (2.2) |

|

ISR, mean (SD) Depressive disorders Anxiety disorders Obsessive-compulsive disorders Somatoform disorders Eating disorders Additional items Total |

1.7 (0.7) 1.4 (1.1) 1.1 (1.0) 0.9 (0.9) 0.7 (0.8) 0.9 (0.5) 1.1 (0.5) |

1.7 (0.7) 1.1 (0.8) 1.0 (0.8) 0.7 (0.7) 1.1 (1.1) 0.9 (0.4) 1.1 (0.4) |

1.7 (0.7) 1.2 (0.9) 1.0 (0.9) 0.8 (0.8) 0.9 (1.0) 0.9 (0.5) 1.1 (0.5) |

MBI-GS-D: Maslach Burnout Inventory–General Survey; PSQ: Perceived Stress Questionnaire; WHO-5: World Health Organization 5-item Well-Being Index;

EQ-5D: EuroQol (EQ-5D); ISR: ICD-10-Symptom-Rating

The mean age was 50.9 years (±6.9). Most participants were female (76.1%), married or cohabiting (63.6%), and highly educated. Almost all participants were in paid employment (94.3%). They represented a wide range of occupations, including e.g. healthcare professionals, administrative employees, and commercial staff. With one exception, all participants were insured by the statutory health insurance Barmer GEK. The mean number of sick days during the previous six months was 10.6 (±18.3) per participant. 26.1% had no sick days during that period. The average PSQ_total at baseline was 68.4 (±13.4), which was considerably higher than in healthy adults with a mean of 33 (27). Participants had a mean MBI-EE of 4.4 (±0.6). Among the psychological symptoms, the highest values were found in the depression (M 1.7 ± 0.7) and the anxiety (M 1.2 ± 0.9) scales. Both values can be interpreted as symptoms of low-to-medium levels of strain.

Change in PSQ_total and secondary outcomes

Results regarding the changes over time in PSQ_total and secondary outcomes compared between groups are presented in Table 2 and Figure 2. While there were no significant differences in means found across the groups at baseline, the mean change scores (changes compared to baseline) differed significantly between them at all post-intervention time points. The participants in the IG showed significant improvements compared to the controls. ANCOVA revealed significant effect between groups (PSQ_total at T4 in PP-analysis: –25.43; 95%CI [-31.09; -19.77]), confirmed by ITT-analysis (-20.57; 95%CI [-26.09; -15.04]). Large effect sizes, even in ITT-analysis (Cohen‘s d for PSQ_total 1.09–1.72), indicate the superiority of the intervention group compared to the waiting control group.

Table 2. Changes in outcomes from baseline to 1, 3, and 6-month follow-up post-intervention among study completers (PP-analysis, N=88) and ITT-analysis for the primary outcome PSQ_total considering all randomized persons (participants N=90 and non-participants N=19) with missing value imputation using the “Last Observation Carried Forward” method.

| Intervention Group | Waiting Control Group | |||||||||

| Change from baseline | Change from baseline | Change from baseline – Difference between groups | Effect size | Between-group ANCOVA*1 | ||||||

| N | Mean | SD | N | Mean | SD | Mean [95%CI] | Pooled SD | Cohen’s d | Parameter estimate for group [95%CI] | |

| PSQ_total (PP) | ||||||||||

| at 1 month | 43 | –33.45 | 14.21 | 45 | –1.85 | 9.46 | –31.60 [–37.07; –24.61]*2 | 12.02 | –2.63 | –31.37 [–36.20; –26.54]*4 |

| at 3 months | 43 | –27.13 | 15.70 | 44 | –5.64 | 15.49 | –21.49 [–28.25; –13.50]*2 | 15.59 | –1.38 | –21.27 [–27.65; –14.89]*4 |

| at 6 months | 43 | –28.33 | 16.50 | 44 | –2.84 | 10.77 | –25.49 [–32.13; –18.46]*2 | 13.90 | –1.83 | –25.43 [–31.09; –19.77]*4 |

| PSQ_total (ITT) | ||||||||||

| at 1 month | 54 | –26.64 | 18.57 | 55 | –1.73 | 8.67 | –24.91 [–31.42; –18.45]*2 | 14.45 | –1.72 | –24.92 [–30.27; –19.56]*4 |

| at 3 months | 54 | –21.60 | 17.81 | 55 | –3.94 | 14.51 | –17.66 [–24.60; –10.78]*2 | 16.23 | –1.09 | –17.67 [–23.67; –11.68]*4 |

| at 6 months | 54 | –22.56 | 18.67 | 55 | –2.00 | 10.00 | –20.56 [–27.20; –13.97]*2 | 14.94 | –1.38 | –20.57 [–26.09; –15.04]*4 |

| WHO-5 (PP) | ||||||||||

| at 1 month | 43 | 32.65 | 16.28 | 45 | 3.47 | 15.27 | 29.18 [22.76; 38.04]*2 | 15.77 | 1.85 | 29.60 [23.23; 35.96]*4 |

| at 3 months | 43 | 24.09 | 18.75 | 44 | 5.18 | 14.78 | 18.91 [11.29; 28.51]*2 | 16.86 | 1.12 | 19.15 [12.09; 26.21]*4 |

| at 6 months | 43 | 23.44 | 20.80 | 44 | 2.18 | 15.42 | 21.26 [14.95; 31.54]*2 | 18.28 | 1.16 | 22.07 [14.67; 29.48]*4 |

| MBI_EE (PP) | ||||||||||

| at 1 month | 42 | –1.08 | 0.79 | 45 | 0 | 0.55 | –1.08 [–1.30; –0.71]*2 | 0.68 | –1.59 | –1.05 [–1.31; –0.79]*4 |

| at 3 months | 42 | –1.06 | 0.72 | 44 | 0.07 | 0.56 | –1.13 [–1.38; –0.70]*2 | 0.64 | –1.77 | –1.11 [–1.38; –0.84]*4 |

| at 6 months | 41 | –1.03 | 0.95 | 45 | 0.08 | 0.54 | –1.11 [–1.44; –0.68]*2 | 0.76 | –1.46 | –1.10 [–1.42; –0.78]*4 |

| EQ5D_Health state (PP) | ||||||||||

| at 1 month | 42 | 21.12 | 15.86 | 45 | 2.18 | 17.35 | 18.94 [9.39; 21.27]*2 | 16.65 | 1.14 | 16.55 [10.95; 22.15]*4 |

| at 3 months | 42 | 17.07 | 19.31 | 45 | 1.64 | 17.35 | 15.43 [4.90; 17.85]*3 | 18.32 | 0.84 | 12.85 [6.60; 19.09]*5 |

| at 6 months | 42 | 19.71 | 16.93 | 43 | 3.67 | 16.97 | 16.04 [5.29; 18.43]*3 | 16.95 | 0.95 | 13.74 [7.69; 19.79]*4 |

*1 Between-group ANCOVA adjusted for baseline values (in the case of non-participants values from eligibility testing were used)

*2 p-value for t-test comparison of means between groups <0.0001;

*3 p-value for t-test comparison of means between groups <0.001

*4 p-value for between-group ANCOVA <0.0001;

*5 p-value for between-group ANCOVA <0.001

eFIGURE 1.

Participants flow

At baseline, 96.6% of participants reported having had back pain during the previous two weeks. The mean pain intensity was 5.5 (± 2.2). Compared to the WG, the participants in the IG showed significant decreases in both the frequency and intensity of back pain post-intervention and during follow-up (table 3).

Table 3. Back pain frequency and intensity from baseline to 1, 3, and 6-month follow-up post-intervention among study completers (PP analysis, N=88).

| Baseline | 1-month follow up | 3-month follow up | 6-month follow up | |||||||||

| IG | WG | p-value | IG | WG | p-value | IG | WG | p-value | IG | WG | p-value | |

| Back pain frequency, n (%) | ||||||||||||

| none | 2 (4.7) |

1 (2.2) |

9 (20.9) |

2 (4.6) |

7 (16.7) |

4 (8.9) |

6 (14.0) |

0 (0.0) |

||||

| from time to time | 9 (20.9) |

12 (26.7) |

27 (62.8) |

15 (34.1) |

21 (50.0) |

17 (37.8) |

23 (53.5) |

19 (42.2) |

||||

| periodically | 11 (25.6) |

16 (35.6) |

4 (9.3) |

13 (29.6) |

10 (23.8) |

6 (13.3) |

6 (14.0) |

9 (20.0) |

||||

| often | 8 (18.6) |

7 (15.6) |

0 (0.0) |

9 (20.5) |

3 (7.1) |

9 (20.0) |

4 (9.3) |

7 (15.6) |

||||

| very often/ permanently |

13 (30.2) |

9 (20.0) |

3 (7.0) |

5 (11.4) |

1 (2.4) |

9 (20.0) |

4 (9.3) |

10 (22.2) |

||||

|

Back pain frequency (median) |

periodically | periodically | 0.3277*1 | from time to time |

periodically | < 0.0001*1 | from time to time |

periodically | 0.0089*1 | from time to time |

periodically | 0.0042*1 |

|

Back pain intensity, mean (SD) |

5.40 (2.43) |

5.58 (1.92) |

0.9863*2 | 2.98 (2.21) |

5.21 (2.38) |

< 0.0001*2 | 3.49 (2.20) |

5.38 (2.66) |

0.0009*2 | 3.88 (2.45) |

5.14 (2.28) |

0.0253*2 |

Frequency data are presented as number (%) of participants who reported the respective back pain frequency (each based on the past 2 weeks).

*1 p-value of the Mann-Whitney-U-test for back pain frequency; *2 p-value of the t-test for back pain intensity; PP, per protocol; SD, standard deviation

Both groups had fewer sick days during the 6-month follow-up (median IG=1, WG=2) compared to the 6-month period prior to the start of the study (median IG=5, WG=4). There was no statistically significant difference between the two groups. No adverse events were reported.

Discussion

The multimodal prevention program aimed at reducing currently perceived stress, but also at providing strategies for dealing with stressors in everyday life and, thus, enabling participants to help themselves in the long run.

Participants were 76% female, on average 51 years old, and most had a higher education. This corresponds to the results of population-based Scandinavian studies, where higher levels of burnout and exhaustion were associated with female sex (31), being older (>50) (8, 31) and having either a higher education or no education (8).

Participants of the IG experienced significant immediate improvement in perceived stress and secondary outcomes, which declined somewhat during the first three months post-intervention and then lasted for at least another three months, while the WG did not change substantially across time. Change over time in the IG yielded large effect sizes, suggesting significant improvement in psychological functioning post-intervention and over the course of the follow-up. The results of an ITT-analysis for PSQ_total are consistent with the primary PP-analysis.

Many studies have recently been conducted on the effectiveness of interventions that aim at reducing occupational stress and/or preventing burnout (7, 19– 21).

Our study has a lot in common with these studies: the study population was mainly female and consisted of individuals from a wide range of occupations with increased stress levels and/or at risk of burnout; a secondary preventive approach was generally applied; burnout, stress and mental health were target outcomes; and cognitive behavioral intervention (CBI) was a key intervention. In contrast, differences exist in both the nature and scope of the interventions and in their duration.

Most burnout–prevention studies investigated the effects of person-directed interventions involving measures such as CBI, communication training, relaxation and others. In 75% of these person-directed studies, burnout decreased significantly (20). Even research on the effects of occupational stress-management interventions included CBI, which was the second-most-common intervention (56%) after relaxation and meditation techniques (69%). Often both forms of therapy were combined. CBIs were found to consistently produce larger effects than other types or combinations of interventions (21). Physical exercise as a stress-reducing measure was rarely investigated.

The majority of these studies included intervention periods of several weeks or months. It can be assumed that most of the treatment sessions were held intermittently at the place of residence or work. This differs greatly from our 3-week treatment at a health resort, which not only offered a comprehensive multimodal program, but also a spatial distance from home and work, which gave participants the opportunity to get away from the stressors of daily life.

One previous study examined the effectiveness of health resort treatments on work-related burnout (32). The treatment offered in this research project was not primarily designed as burnout prevention. Participants were at the Austrian health resort because of musculoskeletal complaints, but also showed symptoms of burnout. They received the usual individualized spa treatment. A specific SMI was not carried out. Considerable improvement in burnout-related complaints was achieved and lasted up to three months. However, the lack of a control group greatly limits the validity of these results.

The improvements seen in our study are altogether comparable to previous research. The results in Table 2 reveal large effect sizes for perceived stress, well-being, emotional exhaustion, and general health during the 6-month follow-up. Richardson and Rothstein show in their meta-analysis of 36 studies evaluating the effectiveness of SMIs that CBIs are the only interventions with similarly large effect sizes. In contrast, multimodal interventions comprising cognitive-behavioral or relaxation components or both yielded significant, albeit small, effect sizes. Interestingly, they found that the more components were added to a CBI, the less effective it became (21). This is contrary to our findings, in which a multimodal intervention including SMI, relaxation, physical exercise and moor applications was highly effective in reducing perceived stress and burnout symptoms in the short-to-medium term.

It can be assumed that the 3-week absence from home and work also contributed to the observed changes. Previous research has found that respite from work and the daily workload has small, but positive, effects on health and well-being and can reduce perceived stress and experienced burnout. The recovery effects, however, are of short duration. Both, perceived stress and burnout symptoms, decrease during vacation and increase after returning home (33, 34).

Our present study could not answer the question of whether the program is more or less effective for particular subgroups (e.g., differentiation according to age group, sex, educational background, etc.). Longitudinal data analyses based on the whole data set will be conducted to examine this partial aspect.

The question of which specific interventional measures are essential for efficiently reducing stress and burnout was not investigated in the scope of this study. In previous studies, stress-reducing or anti-depressive effects were demonstrated for most therapeutic measures applied in our prevention program (35– 39). However, previous research on burnout prevention suggests that SMIs could play a crucial role (20).

Limitations to this study comprise the potential bias of self-report and the lack of additional parameters known to potentially influence perceived stress and burnout symptoms (e.g., personality traits, social support). The use of a voluntary sample may include only the most motivated people, and therefore limits the generalizability. The WG design is controversial because of the potential overestimation of treatment effects. Nevertheless, it is a common and sensible approach in the evaluation of SMIs (21) providing advantages in ethical (guarantees treatment) and methodological (controls for time, regression to mean, and expectancy of improvement) terms (40). As a final point, the possibility cannot be excluded that results may be biased due to the lack of blinding, which is not feasible in a trial with WG design.

Strengths of the study include the use of well-validated assessment tools, the conscientiousness of the participants, the impressive response rate and completeness of data, as well as the low drop-out rate.

As noted above, our study participants were selected based on their level of perceived stress and the extent of burnout symptoms. It is uncertain whether the results of this study can be generalized to all populations at risk of burnout. For our study population, however, we could clearly show the feasibility of this health-resort-based program, its positive effects on perceived stress and other health-related outcomes and its high general acceptance.

Supplementary Material

eMETHODS

Study population

Participants were recruited through printed and electronic advertisements (study website, flyers, local newspapers and the membership magazine of the cooperating health insurance company Barmer GEK) in the period from mid-December 2013 to the end of February 2014. Interested persons were invited to complete two screening questionnaires, the MBI–General Survey (MBI-GS-D) (24, 25), and the Perceived Stress Questionnaire (PSQ) (26, 27). The study population was defined as individuals with an above-average level of stress who were at increased risk for developing a burnout syndrome.

Eligibility Criteria

Inclusion criteria were:

Exclusion criteria were acute or chronic health disorders that represent a contraindication to the administration of full moor baths (e.g., reduced cardiovascular capacity, skin diseases). Those who failed to meet these selection criteria due to increased values on the MBI-EE were advised to contact their general practitioner for clarification.

Intervention Program

The IG took part in a 3-week prevention program including four key therapeutic elements:

(1) SMI on burnout prevention (10x2h, in groups of 8–12 participants),

(2) relaxation techniques: Hatha-Yoga (5x1h), Qigong (5x1h), mindfulness training (10x20min) and progressive muscle relaxation (6x1h),

(3) Physical exercise: Back school (7x1h) and endurance sports activities (7x1h) and

(4) Moor applications (7 x full moor baths (42°C, 20 minutes) followed by a resting period and massage (20 minutes each).

A moor bath is prepared using moor mud (peat pulp) consisting of organic matter, minerals and water. It is widely used therapeutically as part of balneotherapy in European health resorts (especially in Germany, Austria, Poland, and the Czech Republic). Moor mud applications in the form of packs and baths are used to treat a multitude of complaints, mainly in musculoskeletal disorders.

A stress-reducing or anti-depressive effect has previously been demonstrated for most of the therapeutic procedures (35– 39) used in our intervention program. The program was carried out in the Bavarian health resort of Bad Aibling in March/April 2014 (two 3-week periods, each with two parallel groups of up to 12 participants). Participants in the WG had to wait for six months before they were allowed to take part in the same program in October/November 2014.

The SMI is based on the group-therapy program for burnout developed for inpatients of the Psychosomatic Clinic in Windach, Germany. The program has been shortened and modified for prevention purposes. Mainly following a psychoeducational approach combined with exercises in mindfulness-based therapy, the seminar essentially covers the following topics: explaining what the burnout process and syndrome are, including the role of stress in the development of the symptomatology; giving a basic understanding of the neurobiology and neuroendocrinology of stress processes; introducing psychological stress models (e1) to provide participants with knowledge about the possible health effects of excessive stress and how to assess their own risk; group discussions where participants are encouraged to share their personal experiences, discuss professional and psychosocial stressors leading to burnout and reflect on possibilities of prevention by changing occupational conditions; explaining that the burnout-syndrome is not only a problem of professional stress, but influenced by a variety of personality traits (e2– e4); and reflecting on and changing attitudes and behavior that could help prevent stress-related disorders. Participants were encouraged to define personal goals and values, to become aware of possible conflicts of interests with employers or society and to discuss resulting consequences. Basic stress-management tools, like task management, setting limits in everyday professional life and delegating tasks, as well as self-care, sleep hygiene, regeneration, leisure and enjoyment complete the program.

The SMI was performed by two psychologists experienced in the treatment of burnout. All exercise and relaxation courses were carried out by experienced therapists. The moor applications were given in two local rehabilitation clinics and one spa treatment center.

Legal Background

The formal and legal framework for the prevention program is an outpatient prevention measure in accordance with § 23.2 SGB V (Volume V of the German Social Insurance Code). This implies that participants

Costs of medical and therapeutic services are covered by the statutory health insurance.

Sample-size estimation

Sample-size estimation was based on the primary outcome perceived stress (PSQ_total) at T4. Presuming an effect size of 0.35, a power of 0.8 and a significance level of 0.05 resulted in an estimated sample size of n=82 for the total group when using analysis of covariance (ANCOVA). A total sample of 90 participants had to be recruited for an estimated drop-out rate of 10%.

Missing data handling

Individual missing items in the standardized questionnaires (see Outcomes and Measures in the Methodssection) were replaced, where appropriate, in compliance with the instructions of the questionnaires’ developers.

In line with the ITT principle, an analysis concerning the primary outcome PSQ_total was conducted, taking into consideration all randomized persons. For this analysis, missing PSQ data were replaced using the Last Observation Carried Forward (LOCF) method (e5). For non-participants (left the study between randomization and baseline assessment because they could not comply with the time schedule; no baseline data available) PSQ values from eligibility testing during the recruitment phase were used as baseline data.

Statistics software

Statistical analyses were performed using the R version 2.15.2 and SPSS 23.0.

age 18–70 years,

risk of burnout or incipient burnout syndrome (Emotional Exhaustion Scale [MBI-EE] of the MBI-GS-D 3.6–5.2),

above-average level of perceived stress (PSQ_total ≥ 50, which corresponds to the mean plus one standard deviation in healthy adults (27)),

adequate fitness and a general health status enabling participation in the program and toleration of moor baths and

being insured with the Barmer GEK or a self-paying patient.

have to follow the usual formalities for applying for an outpatient prevention measure at a health resort;

must not have received an outpatient prevention measure at a health resort in the past three years;

have to pay for their accommodation, meals, and travel expenses themselves (for residence costs the statutory health insurance granted a subsidy of 8 EUR per day);

usually have to take vacation for the duration of the measure, unless otherwise agreed on with their employer.

Key Messages.

The 3-week preventive program combining classical elements of health-resort medicine with stress-management interventions has the potential to reduce perceived stress, emotional exhaustion and other target parameters in adults presenting with an above-average level of stress and increased risk of burnout.

Significant improvements were maintained over a period of at least 6 months post-intervention.

There is a great demand for this kind of intervention aiming at reducing perceived stress and providing strategies for dealing with stressors in everyday life.

People afflicted are willing to invest time (three weeks of vacation) and money (travel, accommodation, meals) to participate in this program.

Future research should examine the long-term impact (>6 months) of the program and the effect of occasional refresher training.

Acknowledgments

We wish to offer our sincere thanks to all our study participants for their commitment and patience, which made the success of our study possible. A tribute also needs to be paid for the valuable support in conducting the study on site provided by our colleagues Gisela Immich and Michaela Kirschneck.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München, Germany (study no. 547–13). Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Registration

German Clinical Trials Register: DRKS00009625

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The study was funded by the Bavarian State Ministry of Health and Care (Grant No. K1–04–00014–2012-EA_BayGA). Applicants in this scheme, in this case the health resort administration of Bad Aibling (AibKur), have to provide a financial contribution of 30% of eligible expenditure. The costs of medical and therapeutic services were covered by Barmer GEK.

The funding agencies had no influence on the planning and course of the study or on the evaluation and publication of its findings.

The Chair of Public Health and Health Services Research, LMU has received study support (third-party funding for the research project).

All authors declare that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- 1.Lohmann-Haislah A. Stressreport Deutschland 2012 - Psychische Anforderungen, Ressourcen und Befinden Dortmund/Berlin/Dresden. Bundesanstalt für Arbeitsschutz und Arbeitsmedizin. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bundespsychotherapeutenkammer. BPtK-Studie zur Arbeitsunfähigkeit - Psychische Erkrankungen und Burnout. www.bptk.de/uploads/ media/20120606_AU-Studie-2012.pdf (last accessed on 28 June 2016) [Google Scholar]

- 3.DRV-Bund. Deutsche Rentenversicherung Bund. Berlin; 2015. Rentenversicherung in Zeitreihen - DRV-Schriften Band 22. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bianchi R, Schonfeld IS, Laurent E. Burnout-depression overlap: a review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2015;36C:28–41. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2015.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaschka WP, Korczak D, Broich K. Burnout: a fashionable diagnosis. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2011;108:781–787. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2011.0781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schaufeli WB, Leiter MP, Maslach C. Burnout: 35 years of research and practice. Career Dev Int. 2009;14:204–220. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Awa WL, Plaumann M, Walter U. Burnout prevention: a review of intervention programs. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;78:184–190. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ahola K, Honkonen T, Isometsa E, et al. Burnout in the general population Results from the Finnish Health 2000 Study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2006;41:11–17. doi: 10.1007/s00127-005-0011-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scheuch K, Haufe E, Seibt R. Teachers’ health. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2015;112:347–356. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2015.0347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Honkonen T, Ahola K, Pertovaara M, et al. The association between burnout and physical illness in the general population—results from the Finnish Health 2000 Study. J Psychosom Res. 2006;61:59–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2005.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peterson U, Demerouti E, Bergstrom G, et al. Burnout and physical and mental health among Swedish healthcare workers. J Adv Nurs. 2008;62:84–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04580.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ekstedt M, Soderstrom M, Akerstedt T, et al. Disturbed sleep and fatigue in occupational burnout. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2006;32:121–131. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Taris TW. Is there a relationship between burnout and objective performance? A critical review of 16 studies. Work Stress. 2006;20:316–334. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ahola K, Kivimaki M, Honkonen T, et al. Occupational burnout and medically certified sickness absence: a population-based study of Finnish employees. J Psychosom Res. 2008;64:185–193. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bianchi R, Schonfeld IS, Laurent E. Burnout: Absence of binding diagnostic criteria hampers prevalence estimates. Int J Nurs Stud. 2015;52:789–790. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2014.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Korczak D, Wastian M, Schneider M. Schriftenreihe Health Technology Assessment, Band 120 Deutsches Institut für Medizinische Dokumentation und Information (DIMDI) Köln; 2012. Therapie des Burnout-Syndroms. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bundesministeriums für Arbeit und Soziales (BMAS)/Bundesanstalt für Arbeitsschutz und Arbeitsmedizin (BAuA) Sicherheit und Gesundheit bei der Arbeit 2011. www.baua.de/suga (last accessed on 26 June 2016) [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bundesanstalt für Arbeitsschutz und Arbeitsmedizin (BAuA) Volkswirtschaftliche Kosten durch Arbeitsunfähigkeit 2013. www.baua.de/de/Informationen-fuer-die-Praxis/Statistiken/Arbeitsunfaehigkeit/Kosten.html (last accessed on 26 June 2016) [Google Scholar]

- 19.van der Klink JJL, Blonk RWB, Schene AH, et al. The benefits of interventions for work-related stress. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:270–276. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.2.270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Walter U, Plaumann M, Krugmann C. Burnout Interventions Burnout for experts—prevention in the context of living and working. In: Bährer-Kohler S, editor. Springer Science+Business Media. New York; 2013. pp. 223–246. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Richardson KM, Rothstein HR. Effects of occupational stress management intervention programs: a meta-analysis. J Occup Health Psych. 2008;13:69–93. doi: 10.1037/1076-8998.13.1.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hillert A. [How is burnout treated? Treatment approaches between wellness, job-related prevention of stress, psychotherapy, and social criticism] Bundesgesundheitsbla. 2012;55:190–196. doi: 10.1007/s00103-011-1411-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gutenbrunner C, Bender T, Cantista P, et al. A proposal for a worldwide definition of health resort medicine, balneology, medical hydrology and climatology. Int J Biometeorol. 2010;54:495–507. doi: 10.1007/s00484-010-0321-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Büssing A, Glaser J. Technische Universität, Lehrstuhl für Psychologie. München; 1998. Managerial Stress und Burnout, a Collaborative International Study (CISMS), Die deutsche Untersuchung. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schaufeli WB, Leiter MP, Maslach C, Jackson SE. Maslach Burnout Inventory—General Survey (MBI-GS) Maslach burnout inventory manual (3rd edition) In: Maslach C, Jackson SE, Leiter MP, editors. Consulting Psychologists Press. Palo Alto; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fliege H, Rose M, Arck P, et al. Validierung des “Perceived Stress Questionnaire“ (PSQ) an einer deutschen Stichprobe. Diagnostica. 2001;47:142–152. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fliege H, Rose M, Arck P, et al. The Perceived Stress Questionnaire (PSQ) reconsidered: Validation and reference values from different clinical and healthy adult samples. Psychosom Med. 2005;67:78–88. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000151491.80178.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bech P. Measuring the dimension of psychological general well-being by the WHO-5. Quality of Life Newsletter. 2004;32:15–16. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Herdman M, Gudex C, Lloyd A, et al. Development and preliminary testing of the new five-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L) Qual Life Res. 2011;20:1727–1736. doi: 10.1007/s11136-011-9903-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tritt K, von Heymann F, Zaudig M, et al. [Development of the „ICD-10-Symptom-Rating“(ISR) questionnaire] Z Psychosom Med Psychother. 2008;54:409–418. doi: 10.13109/zptm.2008.54.4.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lindblom KM, Linton SJ, Fedeli C, et al. Burnout in the working population: relations to psychosocial work factors. Int J Behav Med. 2006;13:51–59. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm1301_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Blasche G, Leibetseder V, Marktl W. Association of spa therapy with improvement of psychological symptoms of occupational burnout: a pilot study. Forsch Komplementmed. 2010;17:132–136. doi: 10.1159/000315301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Westman M, Eden D. Effects of a respite from work on burnout: vacation relief and fade-out. J Appl Psychol. 1997;82:516–527. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.82.4.516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.de Bloom J, Kompier M, Geurts S, et al. Do we recover from vacation? Meta-analysis of vacation effects on health and well-being. J Occup Health. 2009;51:13–25. doi: 10.1539/joh.k8004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li AW, Goldsmith CAW. The effects of yoga on anxiety and stress. Altern Med Rev. 2012;17:21–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang CW, Chan CHY, Ho RTH, et al. Managing stress and anxiety through qigong exercise in healthy adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2014;14 doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-14-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Koole S. The psychology of emotion regulation: An integrative review. Cognition Emotion. 2009;23:4–41. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rethorst CD, Wipfli BM, Landers DM. The antidepressive effects of exercise A meta-analysis of randomized trials. Sports Med. 2009;39:491–511. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200939060-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Borys C, Nodop S, Tutzschke R, et al. [Evaluation of the German new back school Pain-related and psychological characteristics] Schmerz. 2013;27:588–596. doi: 10.1007/s00482-013-1370-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hart T, Fann JR, Novack TA. The dilemma of the control condition in experience-based cognitive and behavioural treatment research. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2008;18:1–21. doi: 10.1080/09602010601082359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E1.Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Springer; New York: 1984. Stress, appraisal, and coping. [Google Scholar]

- E2.Ilse L, Berberich G, Konermann J, Piesbergen C, Zaudig M. Persönlichkeitsfacetten im DSM-5: Klinische Relevanz bei stressassoziierten Erkrankungen. Persönlichkeitsstörungen. 2014;18:59–66. [Google Scholar]

- E3.Berberich G, Zaudig M, Hagel E, et al. Klinische Prävalenz von Persönlichkeitsstörungen und akzentuierten Persönlichkeitszügen bei stationären Burnout-Patienten. Persönlichkeitsstörungen. 2012;16:85–95. [Google Scholar]

- E4.Zaudig M, Berberich G, Konermann J. Persönlichkeit und Burn-out - eine Übersicht. Persönlichkeitsstörungen. 2012;16:75–84. [Google Scholar]

- E5.Engels JM, Diehr P. Imputation of missing longitudinal data: a comparison of methods. J Clin Epidemiol. 2003;56:968–976. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(03)00170-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMETHODS

Study population

Participants were recruited through printed and electronic advertisements (study website, flyers, local newspapers and the membership magazine of the cooperating health insurance company Barmer GEK) in the period from mid-December 2013 to the end of February 2014. Interested persons were invited to complete two screening questionnaires, the MBI–General Survey (MBI-GS-D) (24, 25), and the Perceived Stress Questionnaire (PSQ) (26, 27). The study population was defined as individuals with an above-average level of stress who were at increased risk for developing a burnout syndrome.

Eligibility Criteria

Inclusion criteria were:

Exclusion criteria were acute or chronic health disorders that represent a contraindication to the administration of full moor baths (e.g., reduced cardiovascular capacity, skin diseases). Those who failed to meet these selection criteria due to increased values on the MBI-EE were advised to contact their general practitioner for clarification.

Intervention Program

The IG took part in a 3-week prevention program including four key therapeutic elements:

(1) SMI on burnout prevention (10x2h, in groups of 8–12 participants),

(2) relaxation techniques: Hatha-Yoga (5x1h), Qigong (5x1h), mindfulness training (10x20min) and progressive muscle relaxation (6x1h),

(3) Physical exercise: Back school (7x1h) and endurance sports activities (7x1h) and

(4) Moor applications (7 x full moor baths (42°C, 20 minutes) followed by a resting period and massage (20 minutes each).

A moor bath is prepared using moor mud (peat pulp) consisting of organic matter, minerals and water. It is widely used therapeutically as part of balneotherapy in European health resorts (especially in Germany, Austria, Poland, and the Czech Republic). Moor mud applications in the form of packs and baths are used to treat a multitude of complaints, mainly in musculoskeletal disorders.

A stress-reducing or anti-depressive effect has previously been demonstrated for most of the therapeutic procedures (35– 39) used in our intervention program. The program was carried out in the Bavarian health resort of Bad Aibling in March/April 2014 (two 3-week periods, each with two parallel groups of up to 12 participants). Participants in the WG had to wait for six months before they were allowed to take part in the same program in October/November 2014.

The SMI is based on the group-therapy program for burnout developed for inpatients of the Psychosomatic Clinic in Windach, Germany. The program has been shortened and modified for prevention purposes. Mainly following a psychoeducational approach combined with exercises in mindfulness-based therapy, the seminar essentially covers the following topics: explaining what the burnout process and syndrome are, including the role of stress in the development of the symptomatology; giving a basic understanding of the neurobiology and neuroendocrinology of stress processes; introducing psychological stress models (e1) to provide participants with knowledge about the possible health effects of excessive stress and how to assess their own risk; group discussions where participants are encouraged to share their personal experiences, discuss professional and psychosocial stressors leading to burnout and reflect on possibilities of prevention by changing occupational conditions; explaining that the burnout-syndrome is not only a problem of professional stress, but influenced by a variety of personality traits (e2– e4); and reflecting on and changing attitudes and behavior that could help prevent stress-related disorders. Participants were encouraged to define personal goals and values, to become aware of possible conflicts of interests with employers or society and to discuss resulting consequences. Basic stress-management tools, like task management, setting limits in everyday professional life and delegating tasks, as well as self-care, sleep hygiene, regeneration, leisure and enjoyment complete the program.

The SMI was performed by two psychologists experienced in the treatment of burnout. All exercise and relaxation courses were carried out by experienced therapists. The moor applications were given in two local rehabilitation clinics and one spa treatment center.

Legal Background

The formal and legal framework for the prevention program is an outpatient prevention measure in accordance with § 23.2 SGB V (Volume V of the German Social Insurance Code). This implies that participants

Costs of medical and therapeutic services are covered by the statutory health insurance.

Sample-size estimation

Sample-size estimation was based on the primary outcome perceived stress (PSQ_total) at T4. Presuming an effect size of 0.35, a power of 0.8 and a significance level of 0.05 resulted in an estimated sample size of n=82 for the total group when using analysis of covariance (ANCOVA). A total sample of 90 participants had to be recruited for an estimated drop-out rate of 10%.

Missing data handling

Individual missing items in the standardized questionnaires (see Outcomes and Measures in the Methodssection) were replaced, where appropriate, in compliance with the instructions of the questionnaires’ developers.

In line with the ITT principle, an analysis concerning the primary outcome PSQ_total was conducted, taking into consideration all randomized persons. For this analysis, missing PSQ data were replaced using the Last Observation Carried Forward (LOCF) method (e5). For non-participants (left the study between randomization and baseline assessment because they could not comply with the time schedule; no baseline data available) PSQ values from eligibility testing during the recruitment phase were used as baseline data.

Statistics software

Statistical analyses were performed using the R version 2.15.2 and SPSS 23.0.

age 18–70 years,

risk of burnout or incipient burnout syndrome (Emotional Exhaustion Scale [MBI-EE] of the MBI-GS-D 3.6–5.2),

above-average level of perceived stress (PSQ_total ≥ 50, which corresponds to the mean plus one standard deviation in healthy adults (27)),

adequate fitness and a general health status enabling participation in the program and toleration of moor baths and

being insured with the Barmer GEK or a self-paying patient.

have to follow the usual formalities for applying for an outpatient prevention measure at a health resort;

must not have received an outpatient prevention measure at a health resort in the past three years;

have to pay for their accommodation, meals, and travel expenses themselves (for residence costs the statutory health insurance granted a subsidy of 8 EUR per day);

usually have to take vacation for the duration of the measure, unless otherwise agreed on with their employer.