Abstract

This study explores the functionalization of main-chain nematic elastomers with a conductive metallic surface layer using a polydopamine binder. Using a two-stage thiol-acrylate reaction, a programmed monodomain was achieved for thermo-reversible actuation. A copper layer (∼155 nm) was deposited onto polymer samples using electroless deposition while the samples were in their elongated nematic state. Samples underwent 42% contraction when heated above the isotropic transition temperature. During the thermal cycle, buckling of the copper layer was seen in the direction perpendicular to contraction; however, transverse cracking occurred due to the large Poisson effect experienced during actuation. As a result, the electrical conductivity of the layer reduced quickly as a function of thermal cycling. However, samples did not show signs of delamination after 25 thermal cycles. These results demonstrate the ability to explore multi-functional liquid-crystalline composites using relatively facile synthesis, adhesion, and deposition techniques.

Keywords: liquid crystalline elastomers, polydopamine adhesion, electroless deposition, actuation

Graphical abstract

A main-chain nematic liquid-crystalline elastomer (LCE) is functionalized with a conductive copper surface via polydopamine adhesion and electroless deposition. The programmed monodomain LCE exhibits thermomechanical contraction up to 42% causing the copper film to buckle reversibly. The film does not delaminate through 25 thermal cycles. These results demonstrate a facile technique to metallize shape-switching polymers.

1. Introduction

Liquid-crystalline elastomers (LCEs) are active polymers that can exhibit large shape changes in response to a stimulus. For example, LCEs can induce strain-related shape changes up to 400% in response to heat (direct conduction, electroresistive heating, inductive heating)1,2 or light (cis-trans photosensitization).3,4 Unfortunately, LCEs have yet to meaningfully translate into the marketplace, in part due to their limited manufacturability. LCEs typically have complex chemistry, synthesis, and programming conditions, all of which pose significant challenges. Furthermore, the current LCE synthesis methods are not practical for large-scale manufacturing and are only used to produce small-scale samples such as thin films5,6 or fibers.7–9 Recently, a novel technique for fabrication of main-chain LCEs has been developed using a two-stage thiol–acrylate Michael addition and photopolymerization reaction.10,11 This approach allows for a significant increase in the size scale of which LCEs can be produced, more precise control over the polymer structure both before and after programming, and a faster and more repeatable reaction mechanism compared to traditional approaches. This new fabrication technique opens the door to potential device applications not previously considered for LCEs.

Despite their unique actuation behavior, LCEs have not been well-explored as a novel hybrid device. For example, deposition of metallic thin-films on elastomeric substrates is a common approach for fabrication of stretchable electronic devices12–16, yet a shape-switching, metallic-coated elastomer would have tremendous potential to further this technology. Even when compared to shape-memory polymers which recover deformation only once, LCEs show repeated shape-shifting indefinately. This opens the possiblity for self-expanding electronics, or an acutator/sensor applications. However, appropriate deposition techniques often rely on specialized equipment necessary for chemical vapor deposition or sputtering, or multi-step techniques such as lithography, which can be expensive. Furthermore, a robust film is critical for usability, and mechanical fracture and/or delamination is known to depend heavily on film thickness and adhesion to the substrate.17–21

An alternative method to metallize non-conductive materials introduced by Lee et al.22 uses an intermediate, nanometer-thick polydopamine (pDA) coating to act as an ‘adhesive layer’ between the substrate and the metallic film. This process is advantageous because a wide variety of polymer substrates can be used, the adhesive layer can be deposited by a simple dip-coating process, and it is relatively inexpensive. However, despite the high research interest (e.g., see reviews23–25), mechanical characterization of pDA-adhered films has not been the focus. Regarding pDA-adhered copper, only recent works by Schaubroeck, et al.26,27 have explicitly investigated macroscopic mechanical adhesion behavior, using a peel test. Results have been promising under certain conditions, mostly related to the surface roughness of the substrate, however, it remains unclear if pDA-adhered films are mechanically stable for practical applications. The purpose of this study is to investigate the feasibility of using pDA as a nano-adhesive mechanism for binding a copper thin film to a shape-switching LCE system capable of large deformation.

2. Results and Discussion

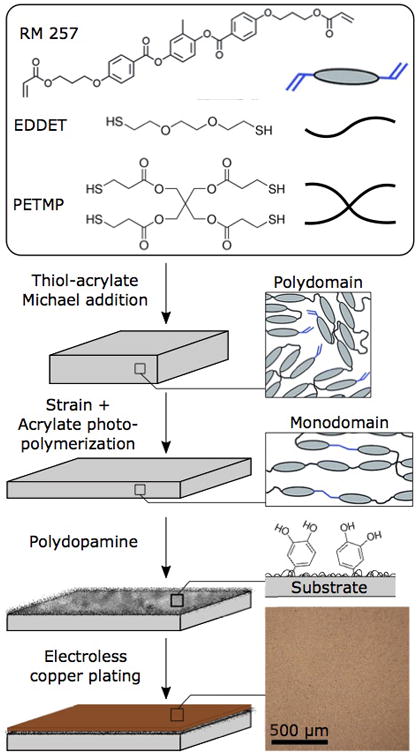

The general methodology for fabrication of the copper-coated LCEs is shown in Figure 1, although detailed information regarding sample fabrication and experimental methodology is provided in the supplemental information. Briefly described, the first step of LCE fabrication is a Michael Addition using a thiol-acrylate ‘click’ reaction. The result is a polydomain elastomer with excess unreacted acrylate groups. The sample is subsequently elongated, aligning the mesogens into a monodomain structure; it is then photo-crosslinked to establish a permanent structure. Consequently, a reversible and repeatable shape change can be induced by heating the LCE through the isotropic phase transition temperature (TI) at 80°C, causing over 40% strain contraction along the director.10,11 Electroless copper deposition is also a two-step process. The elongated LCE is coated with a layer of pDA in an aqueous solution of dopamine, estimated to have a thickness in the nanometer range.22 The pDA-coated specimen is then immediately transferred to an electroless copper plating bath. It is widely accepted that the main reasons for the pDA attachment on a variety of surfaces is the catechol structure along with the ‘crosslink network’ formed via autoxidation22; although it is acknowledged that the precise mechanisms are not fully understood, due in part to the chemically heterogeneous pDA layer. For the LCE, it is expected that the primary bonding method is from the hydrogen-bonding between phenolic hydroxyl groups and hydrogen-bonding acceptors in the thiol-acrylate network. However, covalent bonding with any unreacted thiols in the system is also possible.23 The copper film adheres to the pDA via coordination bonds with the catechol groups. The result is a three tiered structure: copper thin film, adhering pDA nano-layer, and LCE substrate. Experiments performed without the pDA intermediate layer reveal that copper deposits, but readily flakes from the LCE.

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of the LCE fabrication process and subsequent pDA coating and copper plating. The LCE was composed of RM 257 diacrylate, EDDET dithiol, and PETMP tetrathiol monomers with dissolved photo-initiator. The thiol-acrylate stoichiometry was unbalanced such that an excess of acrylate groups remained after a dipropylamine-catalyzed Michael addition reaction which formed a stable polydomain elastomer. The elastomer was uniaxially strained to establish a monodomain and stabilized by photopolymerizing the remaining acrylate groups. LCEs were coated with pDA in an aqueous solution of dopamine and immediately transferred to an electroless copper plating bath. The result was a continuous copper film with minor surface defects.

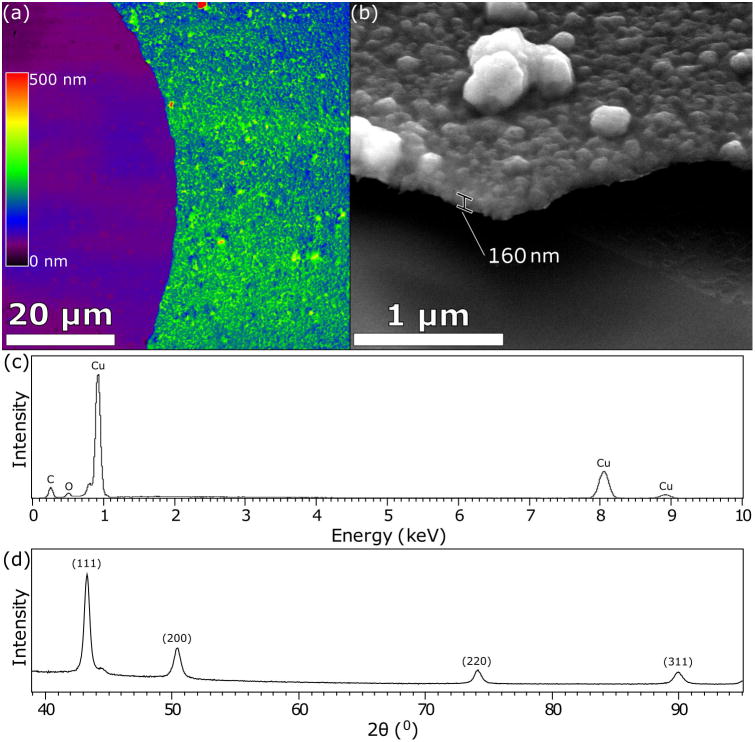

Characterization of the copper films is demonstrated in Figure 2. Figure 2a shows a laser-scanning confocal microscope (LSCM) top-view image of a representative partially coated sample, where only the right-hand side is copper-coated. Due to the inherent roughness of the LCE samples, thickness and roughness measurements proved difficult, and therefore a glass substrate was used instead. It is important to also note that film thickness is a function of the deposition time, here occurring for 8 hrs. Results showed an average film thickness measured to be 150 ± 30 nm (n=3), with an arithmetic mean roughness (Ra) measured to be 80 ± 20 nm (n=3) compared to a substrate roughness less than 10 nm. Film cross-section measurements via scanning electron microscopy (SEM) in Figure 2b reveal similar results, with average film thickness of 160 ± 40 nm (n=3). The X-ray emission spectrum shown in Figure 2c is unique to copper, confirming the elemental make-up of the film. The diffraction pattern obtained by glancing angle x-ray diffraction shown in Figure 2d demonstrates intensity peaks for a variety of crystallographic orientations; this is comparable to a copper powder pattern, demonstrating a polycrystalline film with no obvious preferential growth plane. Taken together, it is concluded that this electroless deposition process results in a continuous, albeit globular copper film. This morphology is characteristic of electroless copper films less than 1 μm thick.28

Figure 2.

(a) LSCM colorized topography data map representing the technique utilized to measure film thickness and surface roughness on glass substrates. Copper film appears on the left with the substrate on the right. (b) SEM image of copper-plated glass substrates fractured prior to imaging to reveal a film cross-section. (c) x-ray emission spectrum of the film generated a set of intense peaks confirming the existence of a copper film. (d) x-ray diffraction pattern obtained by glancing angle diffraction is comparable to a copper powder pattern demonstrating a polycrystalline film with no preferential growth plane.

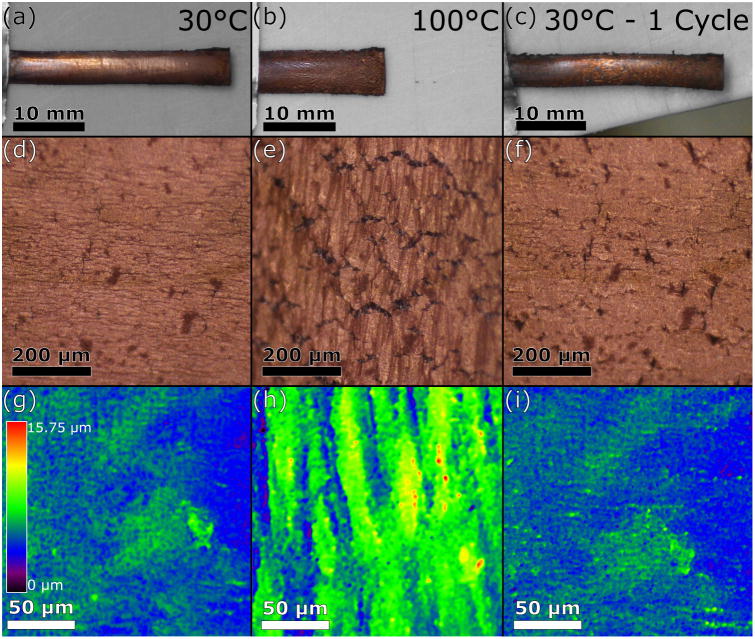

A representative copper-plated LCE thermally cycled through TI is shown in Figure 3. Heating from room temperature through TI caused 42% contraction along the oriented director with accompanying 38% expansion due to Poisson's effect. The substrate fully recovered upon cooling, observed in Figures 3a-c. At low temperature, Figure 3a, the morphology of the as-deposited copper film was representative of the LCE substrate. Upon heating through TI, Figure 3b, the substrate contracted along the director and the adherent film accommodated the large compressive strain. Returning to low temperature (one thermal cycle), the sample assumed its original shape, as shown in Figure 3c.

Figure 3.

Representative copper-plated LCE thermally cycled through TI once. Original samples are displayed in the left column at 30°C. The middle column shows samples at 100°C, having been heated through TI. The right column shows samples after cooling back to 30°C. (a-c) Photographs showing macroscopic sample contraction upon heating and expansion upon cooling. (d-f) High magnification optical images of copper film on LCE substrates obtained by light microscopy. (g-i) Colorized topographical maps of copper film on LCE substrates were obtained by LSCM.

Macroscopic observations indicate the film is stable through thermal cycling, despite the relatively large strains, with no evidence of spalling or delamination. Optical micrographs of copper film on LCE substrates were obtained by light microscopy, shown in Figures 3d-f. In observing the initial, un-cycled state, very few cracks are seen in the image and those that are apparent are perpendicular to the director. As a result of expansion and contraction through the full cycle, cracks begin to form, grow and multiply, and after the first cycle multiple cracks are apparent parallel to the orientation of the director. These cracks are likely the result of the relatively large tensile strain in the transverse direction, just over 35% strain. Crack morphology and spacing is similar to observations for 170 nm copper films well-bonded to a polyimide substrate,21 indicating the pDA forms a relatively strong bond between the LCE and copper film.

Colorized topographical maps of copper film on LCE substrates were obtained by LSCM analysis, shown in Figures 3g-i. Heating the sample initially to 30°C yields a relatively flat surface with variations indicative of the copper film deposited on the LCE substrate and surface profile roughness of 0.71 ± 0.05 μm (n=4). When heated to 100°C the surface becomes much rougher with evidence of buckling of the film perpendicular to the director due to the compression of the LCE with increasing temperature. In the high temperature state, surface profile roughness of 1.15 ± 0.11 μm (n=5) was measured with 12.15 ± 2.35 μm (n=5) average peak-to-valley height and 47.48 ± 10.28 μm (n=6) spacing between peaks. One full thermal cycle of the coated sample produces a similar roughness to the pristine sample, 0.63 ± 0.08 μm (n=4), with discrete areas of the film being more pronounced than the initial state. The recovery of the surface roughness further underlines the buckling of the copper film, as buckling is an elastic deformation mechanism and therefore deformation recovery of the film is expected. Surface buckling is a common observation for thin films on elastomer substrates loaded in compression.15,17

Interestingly, samples were found to be electrically conductive even after one thermal cycle, however, resistance was shown to increase from 123 mΩ/mm2 to 223 mΩ/mm2. Continued thermal cycling resulted in a loss of conductivity. This result is most certainly due to the cracks which formed throughout the film, inhibiting electrical conductivity. Furthermore, resistive heating and deformation recovery of the sample was performed for one cycle, resulting in similar behavior to that shown in Figure 3a-c; although controlled heating was difficult in part due to the thermally insulative nature of the LCE.

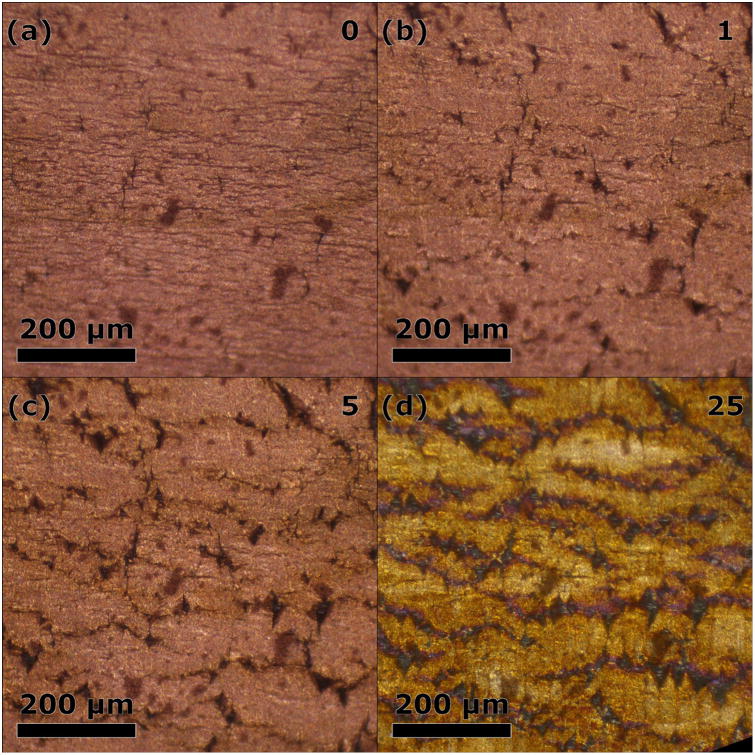

Surface damage over numerous cycles can be seen in the optical microscopy micrographs presented in Figure 4, where a damage progression of the same location is shown for one, five, and 25 cycles. A full cycle transitions the sample from 25°C to 125°C to 25°C at 6°C/min. The slight discoloration after the 25th cycle is attributed to surface oxidation. After the first cycle multiple cracks are apparent parallel to the director; as the cycles continue these cracks propagate, until, by cycle 25 a dense network of cracks is prevalent in the surface. However, even after many cycles, the cracked copper film appears firmly adhered on the LCE substrate.

Figure 4.

Surface damage progression of a copper-plated LCE sample observed by optical microscopy over 25 thermal cycles between 25°C and 125°C at 6°C/min showing (a) few cracks before cycling. Crack propagation and number increases from (b) the first cycle, (c) the fifth cycle, and (d) the 25th cycle. The liquid-crystalline director, oriented left to right, is associated with contraction upon heating.

3. Conclusions

In summary, a facile methodology for creating a robust copper-coated LCE via a pDA adhesive interlayer is presented and observed under thermo-mechanical deformation. The resulting system is a well-adhered copper-film which endures large deformation strains without apparent delamination. Thermal cycling of the LCE reveals micro-cracks throughout the specimen, due primarily to the large tensile loading in the transverse direction, coupled with Poisson's effect during contraction. Multiple thermal cycling results in increased damage progression in the form of an interconnected crack system. Pristine samples are electrically conductive, allowing for resistive heating for thermal activation, but the electrical conductivity decreases quickly from the first cycle due to progressive crack damage. Overall, these experimental results demonstrate the feasibility of electroless copper thin-film deposition on an LCE system capable of high strains. Metal films capable of comparable strains have been demonstrated in the stretchable electronics field, employing geometrical techniques such as film pre-buckling or serpentine interconnects.13 Future work will attempt to harness these techniques in the copper-coated LCE created here, allowing for a robust system that will allow for applications in the future.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

CPF appreciates support from Wyoming NASA EPSCoR (NASA Grant #NNX13AB13A), and from an Institutional Development Award (IDeA) from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Grant #2P20GM103432. CMY thanks NSF-CAREER award (CMMI – 1350436).

Footnotes

Supporting Information is available online from the Wiley Online Library or from the author.

Contributor Information

Carl P. Frick, University of Wyoming, Department of Mechanical Engineering, Laramie, WY, USA

Daniel R. Merkel, University of Wyoming, Department of Mechanical Engineering, Laramie, WY, USA

Christopher M. Laursen, University of Wyoming, Department of Mechanical Engineering, Laramie, WY, USA

Stephan A. Brinckmann, University of Wyoming, Department of Mechanical Engineering, Laramie, WY, USA

Christopher M. Yakacki, University of Colorado Denver, Department of Mechanical Engineering, Denver, CO, USA

References

- 1.Wermter H, Finkelmann H. Liquid crystalline elastomers as artificial muscles. e-Polymers. 2001;13:111–123. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zadoina L, et al. Liquid crystalline magnetic materials. J Mater Chem. 2009;19:8075. [Google Scholar]

- 3.White TJ. Light to work transduction and shape memory in glassy, photoresponsive macromolecular systems: Trends and opportunities. J Polym Sci Part B-Polymer Phys. 2012;50:877–880. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee KM, Koerner H, Vaia RA, Bunning TJ, White TJ. Relationship between the Photomechanical Response and the Thermomechanical Properties of Azobenzene Liquid Crystalline Polymer Networks. Macromolecules. 2010;43:8185–8190. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee KM, Bunning TJ, White TJ. Autonomous, hands-free shape memory in glassy, liquid crystalline polymer networks. Adv Mater. 2012;24:2839–2843. doi: 10.1002/adma.201200374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krause S, Dersch R, Wendorff JH, Finkelmann H. Photocrosslinkable liquid crystal main-chain polymers: Thin films and electrospinning. Macromol Rapid Commun. 2007;28:2062–2068. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ahir SV, Tajbakhsh AR, Terentjev EM. Self-assembled shape-memory fibers of triblock liquid-crystal polymers. Adv Funct Mater. 2006;16:556–560. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang H, et al. Novel liquid-crystalline mesogens and main-chain chiral smectic thiol-ene polymers based on trifluoromethylphenyl moieties. J Mater Chem. 2009;19:7208–7215. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Naciri J, et al. Nematic elastomer fiber actuator. Macromolecules. 2003;36:8499–8505. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saed MO, Torbati AH, Nair DP, Yakacki CM. Synthesis of Programmable Main-chain Liquid-crystalline Elastomers Using a Two-stage Thiol-acrylate Reaction. J Vis Exp. 2016 doi: 10.3791/53546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yakacki CM, et al. Tailorable and programmable liquid-crystalline elastomers using a two-stage thiol–acrylate reaction. RSC Adv. 2015;5:18997–19001. doi: 10.3791/53546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bossuyt F, Vervust T, Vanfleteren J. Stretchable electronics technology for large area applications: Fabrication and mechanical characterization. IEEE Trans Components, Packag Manuf Technol. 2013;3:229–235. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wagner S, Bauer S. Materials for stretchable electronics. MRS Bull. 2012;37:207–213. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rogers JA, Someya T, Huang Y. Materials and Mechanics for Stretchable Electronics. Science (80-) 2010;327:1603–1607. doi: 10.1126/science.1182383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lacour SP, Jones J, Suo Z, Wagner S. Design and performance of thin metal film interconnects for skin-like electronic circuits. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 2004;25:179–181. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Watanabe M, Shirai H, Hirai T. Wrinkled polypyrrole electrode for electroactive polymer actuators. J Appl Phys. 2002;92:4631–4637. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oyewole OK, et al. Micro-wrinkling and delamination-induced buckling of stretchable electronic structures. J Appl Phys. 2015;117:235501. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cordill MJ, Taylor AA. Thickness effect on the fracture and delamination of titanium films. Thin Solid Films. 2015;589:209–214. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Douville NJ, Li Z, Takayama S, Thouless MD. Fracture of metal coated elastomers. Soft Matter. 2011;7:6493–6500. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cordill MJ, Taylor A, Schalko J, Dehm G. Fracture and delamination of chromium thin films on polymer substrates. Metall Mater Trans A Phys Metall Mater Sci. 2010;41:870–875. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xiang Y, Li T, Suo Z, Vlassak JJ. High ductility of a metal film adherent on a polymer substrate. Appl Phys Lett. 2005;87:1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee H, Dellatore SM, Miller WM, Messersmith PB. Mussel-inspired surface chemistry for multifunctional coatings. Science (80-) 2007;318:426–430. doi: 10.1126/science.1147241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang HC, Luo J, Lv Y, Shen P, Xu ZK. Surface engineering of polymer membranes via mussel-inspired chemistry. J Memb Sci. 2015;483:42–59. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Madhurakkat Perikamana SK, et al. Materials from Mussel-Inspired Chemistry for Cell and Tissue Engineering Applications. Biomacromolecules. 2015;16:2541–2555. doi: 10.1021/acs.biomac.5b00852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ye Q, Zhou F, Liu W. Bioinspired catecholic chemistry for surface modification. Chem Soc Rev. 2011;40:4244–58. doi: 10.1039/c1cs15026j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schaubroeck D, et al. Surface Modification of a Photo-Definable Epoxy Resin with Polydopamine to Improve Adhesion with Electroless Deposited Copper. J Adhes Sci Technol. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schaubroeck D, Mader L, Dubruel P, Vanfleteren J. Surface modification of an epoxy resin with polyamines and polydopamine: Adhesion toward electroless deposited copper. Appl Surf Sci. 2015;353:238–244. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Paunovic M. In: Modern Electroplating. Schlesinger M, Paunovic M, editors. John Wiley & Sons; 2011. pp. 433–446. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.