Abstract

We investigated the potential of collagen–genipin sols as biomaterials for treating artificial ulcers following endoscopic submucosal dissection. Collagen sol viscosity increased with condensation, allowing retention on tilted ulcers before gelation and resulting in collagen gel deposition on whole ulcers. The 1.44% collagen sols containing genipin as a crosslinker retained sol fluidity at 23°C for >20 min, facilitating endoscopic use. Collagen sols formed gel depositions on artificial ulcers in response to body temperature, and high temperature responsiveness of gelation because of increased neutral phosphate buffer concentration allowed for thick gel deposition on tilted ulcers. Finally, histological observations showed infiltration of gels into submucosal layers. Taken together, the present data show that genipin-induced crosslinking significantly improves the mechanical properties of collagen gels even at low genipin concentrations of 0.2–1 mM, warranting the use of in situ gelling collagen–genipin sols for endoscopic treatments of gastrointestinal ulcers.

Keywords: collagen, genipin, in-situ gel, fibril formation, ulcer dressing

Introduction

Endoscopy is widely used as a minimally invasive therapy for various diseases of the digestive tract. Endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) and endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) with high-frequency current can be used to remove early gastric cancers of the digestive tract without laparotomy.1–3 Accordingly, these techniques decrease the risk of cancer and reduce the number of patient indications for surgical removal of the digestive tract, thereby increasing healthy life expectancy.

Procedural accidents and complications remain considerable disadvantages of EMR/ESD and include gastric bleeding and perforation by deep ulcers that penetrate the gastrointestinal wall, which are inevitably induced artificially on the digestive tract.4 Treatments for procedural accidents are generally symptomatic and include coagulation of bleeding vessels using hemostatic forceps and immediate closure of acute perforations using endoclips.5 Artificial ulcers are the major cause of complications of endoscopic therapy and occasionally cause gastrointestinal strictures that require treatment with endoscopic balloon dilatation and stent placement,6,7 which also carry risks of acute perforation.8 Hence, because intractable ulcers can progress to delayed perforations,9 prophylactic treatments for procedural accidents and complications are urgently required.

Tissue-engineered cell sheets have been proposed for prophylactic treatments of intractable cancers.10,11 In these studies, tissue-engineered autologous oral mucosal epithelial cell sheets were endoscopically transplanted to esophageal ulcer after ESD, and the formation of esophageal strictures was prevented. Although this therapy was safe and effective, cell sheets could not be introduced into ulcers using “through-the-scope (TTS)” techniques. In addition to the requirement of special devices and techniques to apply these fragile cell sheets to ulcer surfaces, autologous cell cultivation is not suitable for emergency applications.

In contrast with gastrointestinal applications, injectable gels (in situ gelling solutions) are widely considered for plastic surgery. In these applications, dermal wounds are covered with biodegradable injectable gels, such as alginate gels12 and chitosan gels,13 which act as a dressing on the wounds and scaffolds for wound repair. In light of the performance of biodegradable injectable gels as scaffolds for skin wound repair, we investigated the use of gels as biomaterials for prophylactic treatments of artificial ulcers and other procedural accidents and complications of endoscopic therapy. Accordingly, we speculated that gels covering the surface of ulcers could cap the bleeding sites, acting as hemostatic agents that close perforations. The ensuring improvements in repair of artificial ulcers may decrease the incidence of perforation and stricture.

In our previous study, 0.5% collagen sols containing genipin (≤2 mM) maintained fluidity at room temperature for >30 min, caused rapid gelation with increasing temperature from 25°C to 37°C, and then rendered solid gels with genipin-induced crosslinking.14 Hence, in the present study, we investigated the potential of collagen sols as biomaterials for endoscopic treatments of artificial ulcers. The present observations indicate that condensed collagen sols render gel depositions even on tilted ulcers and that collagen gels penetrate into submucosal layers. Taken together, the present observations of collagen condensation, acceleration of temperature-responsive gelation, and subsequent genipin-induced crosslinking warrant further studies of collagen sols as potential in situ gelling materials for TTS application to artificial ulcers.

Materials and methods

Materials

Pepsin-digested collagen from porcine skin in dilute HCl (pH 3; 1% solution of mainly type I collagen; Nipponham Foods Ltd, Osaka, Japan), genipin (Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Ltd., Osaka, Japan), phosphate-buffered saline tablets (Sigma-Aldrich Co., St Louis, MO, USA), disodium hydrogen phosphate (Na2HPO4; Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Ltd.), sodium dihydrogen phosphate (NaH2PO4; Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Ltd.), sodium chloride (NaCl; Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Ltd.), 4% paraformaldehyde solution (Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Ltd.), sucrose (Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Ltd.), 4% carboxymethylcellulose (CMC) sodium salt (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany), ethanol (Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Ltd.), Mayer’s hematoxylin solution, 0.5% eosin Y ethanol solution (Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Ltd.), and raw porcine stomach (Tokyo Shibaura Zouki Co., Tokyo, Japan) were purchased.

Preparation of collagen sols

Various concentrations of collagen solution, genipin solution, and phosphate buffer were prepared in advance. Subsequently, 1% collagen solution in dilute HCl (pH 3) was concentrated to 2.4% in a rotary evaporator at 29°C without denaturing the collagen, and 2 or 6 g aliquots were then placed in 15 mL biological tubes. Genipin was dissolved in ultra-pure water. Standard neutral phosphate buffer (NPB; pH: 7; 1 × NPB) contained 50 mM Na2HPO4/NaH2PO4 and 140 mM NaCl. Concentrated NPB solutions containing (n × NPB; 1 < n ≤ 10) were prepared and stored at room temperature. Collagen and genipin solutions were stored at 4°C.

Various collagen sols were prepared by mixing collagen solutions with genipin solution and/or n × NPB solutions. Genipin and n × NPB solutions were added to collagen solution (2 g or 6 g) and were vigorously shaken in 15 mL biological tubes. Tubes were then centrifuged at 3,200 rpm for 1.5 min to remove air bubbles, and various collagen sols were obtained. The final concentrations of collagen, genipin, and NPB were 0.5%–1.8%, 0–6 mM, and 1.0–2.0 (n of n × NPB), respectively.

Collagen gel preparations for genipin-induced crosslinking tests (described later in Genipin-induced crosslinking section) were modified as follows. Aliquots (3 mL) of 5 mM genipin solution in 5 × NPB were placed in 15 mL biological tubes in a water bath at 23°C or 37°C for certain times. Various genipin solutions were then added to 1% collagen solutions (3 g) in 15 mL biological tubes, and collagen sols were prepared using the procedure described earlier.

Rheological tests of collagen sols

Viscosity

Viscosities of collagen sols were measured in the rotation mode using a rheometer equipped with a Peltier temperature controller (HAAKE MARS III; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Collagen sol aliquots of ~3 mL volume were poured onto the bottom plate of a double-cone sensor DC60/1Ti (diameter of 60 mm, cone angle of 1°), and rotation at a shear rate of 1 s−1 was initiated at 23°C. Viscosity (Pa·s) was calculated according to shear stresses (Pa) and shear rates (s−1).

Temperature-responsive gelation

Temperature-responsive gelation of collagen sols was evaluated using dynamic viscoelastic tests in the oscillation mode under controlled deformation (frequency, 1 Hz; shear deformation, 0.005) with a double-cone sensor, according to previously described methods15 with minor modifications. Briefly, temperature was maintained at 23°C for 5 min, was increased from 23°C to 37°C over 30 s to trigger gelation, and was then maintained at 37°C to promote gelation. Changes in storage (G′) and loss modulus (G″) were registered throughout the test. Gel points were determined according to the time course intersection of G′ and G″,16 and gelation time (tg37) was defined as the time to reach the gel point after the set temperature reached 37°C.

Retention of fluidity

Retention of fluidity of collagen sols at constant temperatures (23°C or 30°C) was evaluated using dynamic viscoelastic tests in the oscillation mode under controlled stress (frequency, 1 Hz; shear stress, 0.01–1 Pa) according to a previously described method15 with minor modifications. Briefly, shear stresses were determined in advance using stress sweep tests to provide a linear viscoelastic regimen, and retention of fluidity of collagen sols was determined according to gelation times (tg23 or tg30), which were defined as the time to reach the gel point at a constant temperature of 23°C or 30°C.

Genipin-induced crosslinking

Genipin-induced crosslinking activities were evaluated using modified temperature-responsive gelation tests and were assessed according to simultaneous gelation times at 23°C and gelation rates at 37°C. Collagen sols were prepared from pre-warmed genipin solutions, and the oscillation mode under controlled stress (frequency, 1 Hz; shear stress, 0.1 Pa; temperature, 23°C) was initiated and maintained until the sample reached gel point (G′ = G″). Following temperature increase to 37°C in 30 s, the oscillation mode was initiated under controlled deformation (frequency, 1 Hz; shear deformation, 0.005; temperature, 37°C) and was maintained to promote gelation. Changes in G′ and G″ were recorded throughout tests.

Delivery load tests of collagen sols through a catheter

Delivery loads of collagen sols through a catheter were measured using a bonding tester (Dage 4000plus; Nordson DAGE, Aylesbury, UK). Collagen sols (5 mL) in 1 × NPB without genipin were introduced into disposable 5 mL syringes (Termo Co., Tokyo, Japan), which were then connected to disposable 1600 mm long catheters (Fine Jet S2816, for Φ 2.8 mm channel; Top Co., Tokyo, Japan) with cutoff tips. Syringes were placed on the bonding tester with a load cell (50 kgf) for shear tests. The plunger of the syringe was pushed at a crosshead speed of 1 mm·s−1, and load–deformation curves were generated. The load at the plateau region in the load–deformation curve was defined as the delivery load.

Analyses of genipin structures

Genipin structures were analyzed using 13C nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy. Genipin solutions (20 mM) in pure water and 5 × NPB were prepared, mixed, and warmed in a water bath at 37°C for 6 h, and aliquots were freeze-dried after filtration through 0.45 μm filters. Aliquots of genipin solution in pure water were freeze-dried immediately after preparation. Freeze-dried samples were dissolved in D2O and loaded into NMR tubes (diameter, 4 mm). Subsequent 13C NMR measurements were performed using a JNM-ECA600 spectrometer (JEOL Resonance Inc., Tokyo, Japan) at the 13C frequency of 150 MHz. All 13C spectra were obtained in the 1H decoupling mode.

Genipin solutions in pure water and warmed solutions in 5 × NPB were diluted with pure water to achieve a genipin concentration of 0.05 mM. Subsequently, absorbance of diluted solutions at 200–300 nm was determined using a spectrophotometer (UV-3100S; Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan).

Mechanical tests of collagen gels

Mechanical properties of collagen gels were evaluated using penetration tests with a mechanical tester (TA.XT plus; Stable Micro Systems, Godalming, UK) according to previously described methods15 with slight modifications. Briefly, aliquots (3 g/well) of collagen sols were poured into six-well biological plates (well diameter, 35 mm) and were placed on the surface of a water bath at 37°C. After 30 min of warming, the plates were sealed with a paraffin film to avoid drying of gels, were moved to an incubator, and were incubated for 24 h at 37°C to complete gelation. After completion of gelation, centers of the gels (n=5) were probed with a cylindrical stainless probe (5 mm in diameter) at a crosshead speed of 0.2 mm·s−1, and stress–strain curves were generated to test penetration. The sensitivity of the mechanical tester was set at 10 Pa. The elastic modulus was calculated from the slope of the stress–strain curve in its linear region (strain from 0.005 to 0.04), in which consolidation of the gels by the biological plates did not affect mechanical data.

Ex vivo gelation tests of collagen gels on artificial ulcers

The application of collagen sols to ESD-induced artificial gastrointestinal ulcers was simulated using ex vivo tests in excised porcine stomachs. Test pieces (60 × 60 mm) were cut from porcine stomachs, and submucosal injections of saline (2 mL) were performed using a 23 G syringe needle. After rising on saline cushions, mucosal layers were resected using a surgical knife to create square artificial ulcers of 30 × 30 mm. Specimens with artificial ulcers were then placed on aluminum plates at an angle of 60° and were then incubated in a digital egg incubator (Rcom Max 20; Autoelex Co., Kyungsangnam-Do, Korea) at 37°C in 70% humidity. Surface temperatures of the specimens were measured using a Horiba infrared thermometer (IT-545; Horiba, Kyoto, Japan). After reaching a surface temperature of 37°C, collagen sols (3 mL) were applied to artificial ulcers and were incubated for 2 h to complete gelation.

Gel adhesion and thickness on ulcer surfaces were evaluated using histological observations. In these analyses, specimens were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, were substituted with 20% sucrose, and were then embedded in 4% CMC. Subsequently, specimens were frozen in a UT-2000F cooling unit (Tokyo Rikakikai Co., Ltd, Tokyo, Japan) at −100°C for 5 min. Sections (20 μm) were then cut using a cryomicrotome (CM3050S; Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany) and were air-dried and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Sections were then washed with a series of increasingly concentrated (70%–99.5%) ethanol solutions, were mounted with Eukitt (ORSAtec GmbH, Bobingen, Germany), and were observed using a BX53 microscope (Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan).

Statistics

Data from penetration tests and thicknesses of gel depositions were expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Differences were identified using one-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey’s tests, and p<0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

Delivery of collagen sols through a catheter

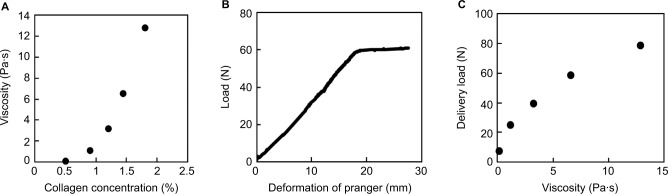

The relationship between viscosity and collagen concentrations of collagen sols (Figure 1A) was determined for collagen sols dissolved in 1 × NPB in the absence of genipin. A 0.5% collagen sol characterized in our previous study14 had a viscosity of 0.12 Pa (shear rate of 1 s−1). Moreover, viscosity increased with collagen concentrations, reaching 12.8 Pa·s at 1.8%. Viscosity curves with stepwise increases in shear rates (1–100 s−1) showed a typical non-Newtonian regime (data not shown). Specifically, the viscosity of the 1.8% collagen sol decreased from 12.8 Pa·s to 0.93 Pa·s with increased shear rates from 1 s−1 to 100 s−1.

Figure 1.

Viscosity and deliverability of collagen sols.

Notes: (A) Collagen sol viscosity as a function of collagen concentrations. Collagen sols were dissolved in standard NPB (1 × NPB) without genipin, and viscosity was determined at a shear rate of 1 s−1. (B) A typical load–deformation curve of 1.44% collagen sols through a catheter. Collagen sols were added to 5 mL disposable syringes and were delivered through a catheter (length, 1,600 mm; diameter, 2.8 mm). (C) Delivery loads of collagen sols as a function of sol viscosity in 1 × NPB without genipin.

Abbreviations: NPB, neutral phosphate buffer.

Delivery load tests were performed to assess deliverability of viscous collagen sols through a catheter. Figure 1B shows a typical load–deformation curve of the 1.44% collagen sols in 1 × NPB in the absence of genipin. This curve comprised a monotonous increase in load and a subsequent plateau region at a constant deformation rate. The monotonous increase in load reflected the filling process of the catheter with collagen sol, and the load at the plateau region was that required for delivery of collagen sol from the tip of the catheter. The delivery load increased with viscosity (Figure 1C). In these experiments, the upper limit of collagen concentration for manually extruding collagen sol was 1.44% (viscosity, 6.6 Pa·s; delivery load, 59 N). When the viscosity reached 12.8 Pa·s (delivery load of 79 N), the syringe containing 1.8% collagen sol was difficult to push through the catheter by hand. Thus, subsequent experiments were performed using 0.5%–1.44% collagen sols.

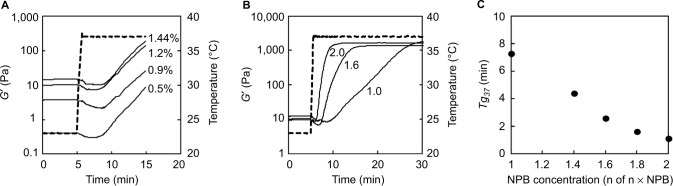

Temperature responsiveness of collagen sol gelation

Temperature-responsive gelation was investigated using 0.5%–1.44% collagen sols in 1 × NPB in the absence of genipin (Figure 2A). After reaching 37°C, G′ decreased and then sharply increased with collagen fibril formation. Although the viscosity of sols and G′ of gels increased with collagen concentration, tg37 differed little (5.0–7.2 min) among collagen sols. However, in contrast to the effects of collagen concentrations, the temperature responsiveness of gelation was increased with increasing NPB concentrations (Figure 2B) and tg37 decreased with increases in NPB concentrations (Figure 2C). Specifically, at an NPB concentration (n of n × NPB) of 2, tg37 was only 1.1 min.

Figure 2.

Temperature responsiveness of collagen sol gelation in the absence of genipin.

Notes: (A) Gelation curves of 0.5%–1.44% collagen sols in 1 × NPB. Numbers in the figure indicate collagen concentrations. Broken lines indicate rheometer set temperatures. (B) Gelation curves of 1.44% collagen sols in n × NPB. Numbers in the figure indicate NPB concentrations (n of n × NPB). Broken lines indicate rheometer set temperatures. (C) Gelation times (tg37) of 1.44% collagen sols in n × NPB in the absence of genipin as a function of NPB concentrations. Gelation times were measured after the temperature reached 37°C.

Abbreviations: NPB, neutral phosphate buffer; min, minutes.

Effects of genipin on temperature responsiveness of collagen sol gelation

Temperature responsiveness of gelation was increased in 1.44% collagen sols in 2 × NPB. Thus, these sols were used to investigate the effects of genipin on temperature responsiveness of collagen sol gelation. In the absence of genipin, G′ rapidly increased immediately after the set temperature reached 37°C and then plateaued within 10 min (Figure 3A). The presence of 0–6 mM genipin had little effect on tg37 (Figure 3B). However, G′ increased continuously in the presence of 6 mM genipin (Figure 3A). Moreover, buildup rates of G′ increased in a genipin concentration-dependent manner (Figure 3C). During temperature-responsive collagen fibril formation under conditions of increased NPB concentrations, genipin-induced crosslinking occurred when collagen fibril formation was almost saturated.

Figure 3.

Temperature responsiveness of collagen sol gelation in the presence of genipin.

Notes: (A) Gelation curves (solid lines) of 1.44% collagen sols in 2 × NPB. Numbers in the figure indicate genipin concentrations, and broken lines indicate rheometer set temperatures. (B) Gelation times of 1.44% collagen sols in 2 × NPB as a function of genipin concentrations. Gelation times were measured after the temperature reached 37°C. (C) Magnified gelation curves (solid lines) of 1.44% collagen sols in 2 × NPB. Numbers in the figure indicate genipin concentrations.

Abbreviation: NPB, neutral phosphate buffer; min, minutes.

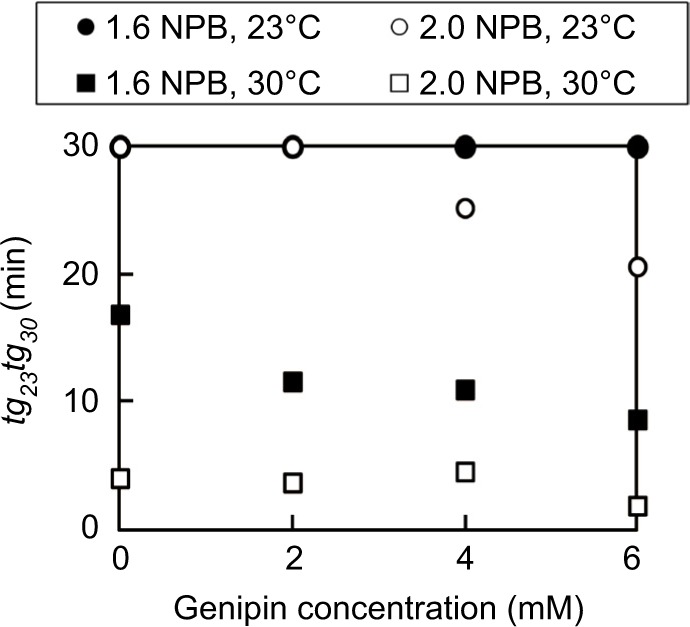

Effects of NPB and genipin on retention of collagen sol fluidity

To determine whether deliverability of sols deteriorated with increasing NPB and genipin concentrations, retention of collagen sol fluidity was evaluated according to tg23 and tg30 (Figure 4). In these experiments, 1.44% collagen sols in 1.6 × NPB containing 0–6 mM of genipin had tg23 of >30 min. However, the increase in NPB concentration from 1.6 to 2 (n of n × NPB) led to a tendency for decreased tg23 with increasing genipin concentrations, reaching 20.6 min at a genipin concentration of 6 mM. At the higher set temperature of 30°C, retention of collagen sol fluidity also deteriorated, and collagen sols in 1.6 × NPB had tg30 of 8.7–16.8 min, which further decreased (1.9–4.1 min) with increasing NPB concentrations from 1.6 to 2 (n of n × NPB). Finally, decreases in genipin concentrations tended to decrease tg30, similar to tg23.

Figure 4.

Effects of temperature and NPB concentrations on gelation times of 1.44% collagen sols.

Abbreviation: NPB, neutral phosphate buffer.

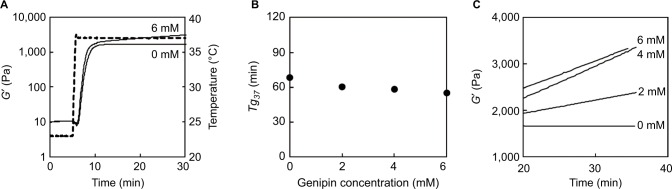

Effects of warming on genipin structure and genipin-induced crosslinking

To investigate changes in genipin structures in collagen sols at 37°C, 5 mM genipin solutions in 5 × NPB were incubated at 37°C in the absence of collagen. Subsequently, formerly transparent and colorless genipin solutions became yellowish and then yellowish brown with time (≤17 h). Moreover, similar color changes in genipin solutions were observed over a few days at 23°C.

In subsequent studies, structural changes in genipin at 37°C were evaluated using 13C NMR and were compared with those of genipin in pure water at room temperature (Figure 5A and B). Several differences in peak intensities and chemical shifts were observed between control and warmed genipin solutions, and a new peak of 180 ppm was observed in the carbonyl carbon region in warmed genipin. Moreover, the peak intensity of C1 (95.9 ppm) in warmed genipin was much lower than that in the control. Finally, peaks of C9 (46.6 ppm) and C6 (35.4 ppm) shifted or disappeared, whereas numerous minor peaks appeared in chemical shifts of 40–60 ppm after warming.

Figure 5.

Effects of warming on genipin structure and genipin-induced crosslinking activities.

Notes: (A) 13C NMR spectra of genipin in pure water. (B) 13C NMR spectra of genipin in 5 × NPB at 37°C for 6 h. (C) UV spectra of genipin in pure water (solid line) and in 5 × NPB at 37°C for 6 h (broken line). (D) Effects of warming times on genipin-induced crosslinking activities at 23°C. Genipin solution (5 mM) in 5 × NPB was incubated at 37°C for 0–17 h and was then mixed with 1% collagen solution to prepare collagen sols. Gelation times at 23°C were determined using rheological tests. (E) Gelation curves of collagen sols at 37°C after reaching gel points (G′ = G″) at 23°C. Numbers in the figure indicate warming times of genipin solutions.

Abbreviations: NMR, nuclear magnetic resonance; NPB, neutral phosphate buffer; UV, ultraviolet; min, minutes.

Spectrophotometric measurements of NMR samples showed clear absorbance at 240 nm (Figure 5C) and a shift to 245 nm in warmed genipin. Moreover, ultraviolet (UV) spectra of warmed genipin solutions had shoulders at wavelengths of 260–300 nm.

Retention of fluidity and temperature responsiveness of gelation were evaluated using rheological tests of 0.5% collagen sols in 2.5 × NPB, which were prepared from control and warmed genipin solutions. In these experiments, tg23 for collagen sols decreased with warming times of genipin solutions (Figure 5D). Moreover, increases in temperature from 23°C to 37°C immediately after sols reached gel points increased gelation, as reflected by increases in G′ (Figure 5E). In addition, rates of increase in G′ were greater with longer genipin incubation times.

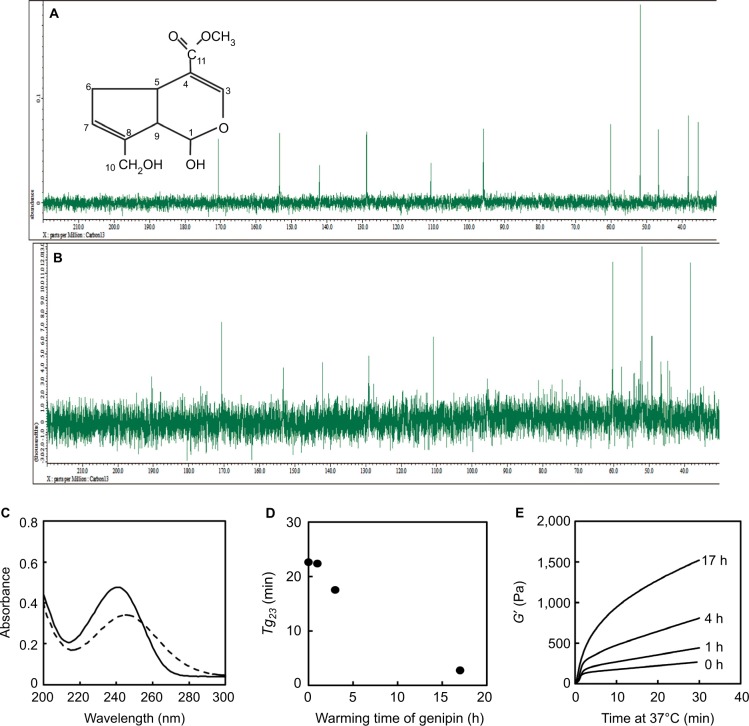

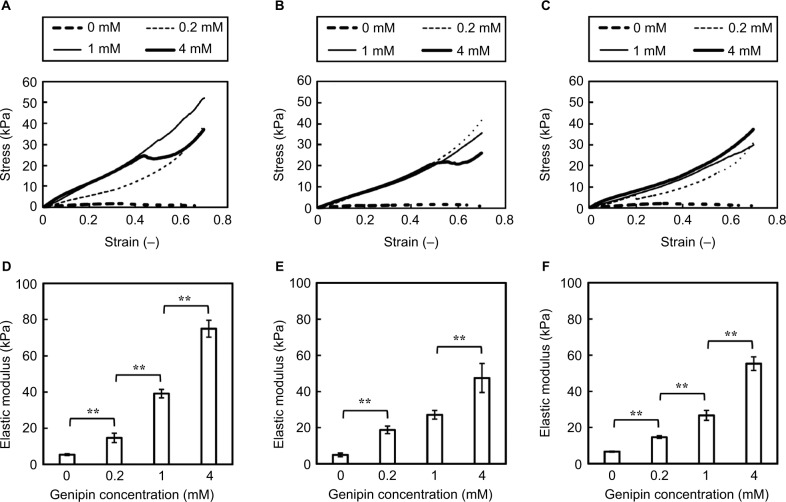

Effects of NPB and genipin on mechanical properties of collagen gels

The effects of NPB and genipin on the mechanical properties of matured collagen gels were investigated using penetration tests of collagen gels. Subsequently, stress–strain curves of gels in 1 × NPB showed enhanced gel strength in the presence of genipin (Figure 6A). Moreover, the overall slopes of stress–strain curves increased with increasing genipin concentrations from 0 mM to 1 mM. However, increases in slope strain of <0.4 plateaued at 4 mM genipin, and gels containing 4 mM genipin showed sudden decreases and then increases in stress during penetration. At NPB concentrations of 1.6 and 2 (n of n × NPB), stress–strain curves of gels were similar at genipin concentrations of 0.2–4 mM, and gels containing 1.6 × NPB and 4 mM genipin or 2 × NPB and 0.2 mM genipin similarly showed sudden decreases and subsequent increases in stress (Figure 6B and C). In contrast, elastic moduli of collagen gels were clearly dependent on genipin concentrations, with minor effects of NPB concentrations (Figure 6D–F). Finally, elastic moduli of collagen gels containing 4 mM genipin were 8.2–13.8 times higher than those containing no genipin, with 2.2–3.8 times greater elastic moduli in the presence of only 0.2 mM genipin.

Figure 6.

Mechanical properties of collagen gels in penetration tests.

Notes: Representative stress–strain curves of 1.44% collagen gels in 1 × NPB (A), 1.6 × NPB (B), and 2 × NPB (C) after incubation at 37°C for 24 h. Numbers in the figure indicate genipin concentrations in sols. Elastic moduli of 1.44% collagen gels in 1 × NPB (D), 1.6 × NPB (E), and 2 × NPB (F) after incubation at 37°C for 24 h. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n=4). Horizontal bars indicate significant differences between samples (**p<0.01).

Abbreviations: NPB, neutral phosphate buffer; SD, standard deviation.

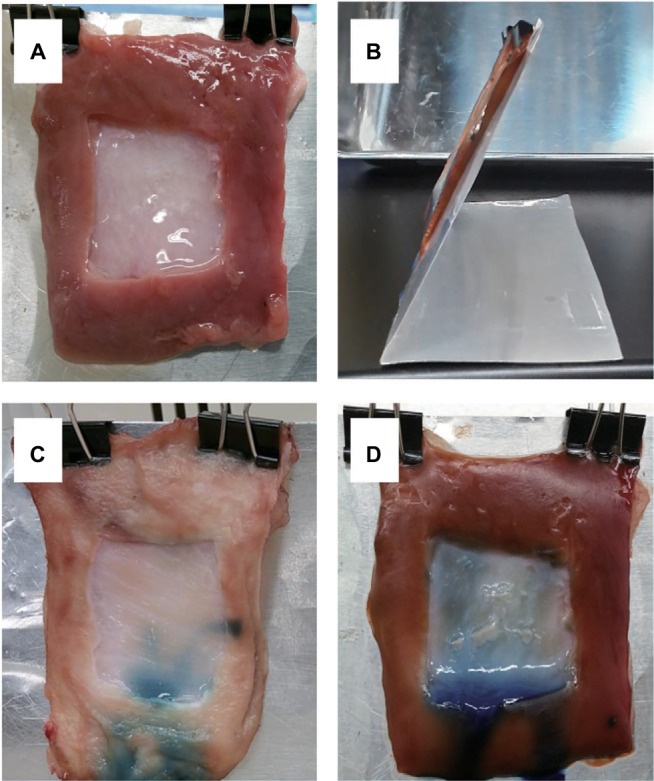

Deposition of collagen gels on artificial ulcers

The gross appearances of ex vivo gelation tests in artificial porcine stomach ulcers are shown in Figure 7. Initially, formation of gel deposition was confirmed using 0.5% collagen sol in 1 × NPB on an artificial stomach ulcer in a horizontal position. However, collagen sols succumbed to gravity prior to gelation when placed on stomach specimens at 60° (Figure 7A and B), resulting in no deposition in the upper and middle regions of the artificial ulcer (Figure 7C), and the residual gel was observed in the bottom pit created by the mucosal layer and the artificial ulcer. In contrast, the 1.44% collagen sols in 2 × NPB formed a gel on the whole ulcer (Figure 7D), as indicated by the bluish color induced by genipin–collagen reactions.

Figure 7.

Ex vivo gelation tests of collagen gels in artificial porcine stomach ulcers.

Notes: (A) Artificial ulcers (30 × 30 mm) were induced in excised stomach tissues and were elongated vertically by gravity. (B) A stomach specimen on an aluminum plate tilted at 60°. (C) Artificial ulcer with 0.5% collagen sol in 1 × NPB containing 4 mM genipin. (D) Artificial ulcer with 1.44% collagen sols in 1.6 × NPB containing 4 mM genipin. Artificial ulcers were elongated by gravity. Stomach specimens (C and D) were stored at 37°C for 2 h after application of collagen sol.

Abbreviation: NPB, neutral phosphate buffer.

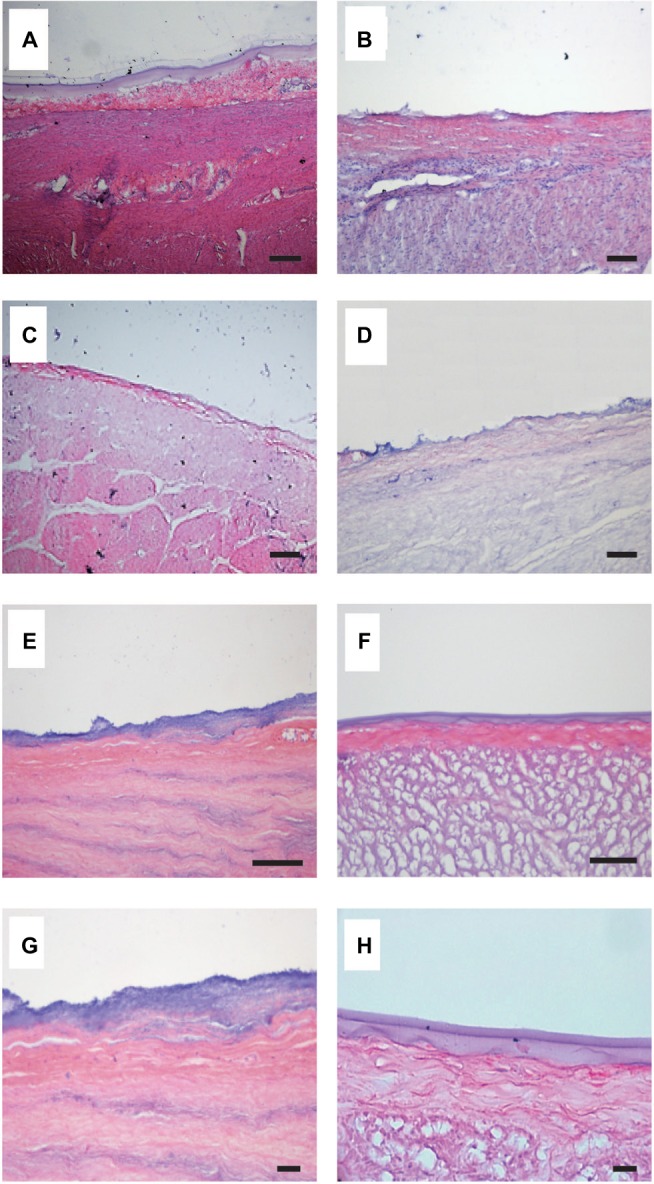

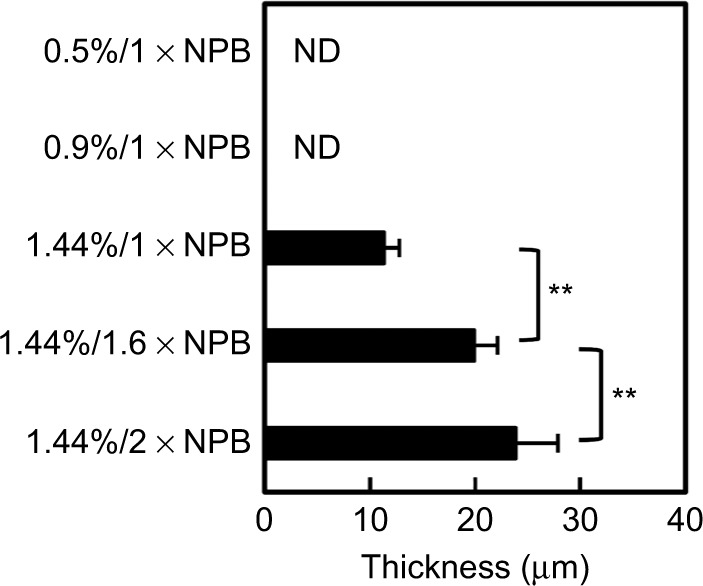

In histological analyses of collagen gel deposition on artificial ulcers (Figure 8A), H&E-stained histological sections of artificial ulcers after application of 0.5% collagen sol in 1 × NPB in the horizontal position showed clear collagen gel deposition on ulcer surfaces. In contrast, no deposition of 0.5% and 0.9% collagen gels was observed after application to stomach specimens tilted at 60° (Figure 8B and C). However, 1.44% collagen sols in 1 × NPB formed a thin gel layer on tilted ulcers (Figure 8D). Increases in NPB concentrations from 1 to 1.6 and 2 (n of n × NPB) at a collagen concentration of 1.44% resulted in thicker collagen gel depositions (Figure 8E and F). In subsequent histological determinations, collagen gel deposits showed increasing thickness with increasing collagen concentrations (Figure 9).

Figure 8.

H&E-stained histological sections of artificial ulcers with collagen sols.

Notes: Stomach specimens were placed horizontally (A) or were tilted at 60° (B–F). (A and B) 0.5% collagen sol in 1 × NPB. (C) 0.9% collagen sol in 1 × NPB. (D) 1.44% collagen sols in 1 × NPB. (E) 1.44% collagen sols in 1.6 × NPB. (F) 1.44% collagen sols in 2 × NPB. Bars indicate 100 µm. (G) Magnification of (E). (H) Magnification of (F). Bars indicate 50 µm.

Abbreviations: H&E, hematoxylin and eosin; NPB, neutral phosphate buffer.

Figure 9.

Thickness of collagen gel coverage on artificial porcine stomach ulcers.

Notes: Thickness (mean ± SD; n=10) was determined from H&E-stained histological sections of artificial ulcers with collagen sols. Numbers on the vertical axis indicate collagen/NPB concentration ratios. ND indicates no gel deposition on artificial ulcers surfaces. Vertical bars indicate significant differences between samples (**p<0.01).

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; H&E, hematoxylin and eosin; NPB, neutral phosphate buffer.

Finally, interfaces between thick collagen gel deposits and submucosal layers were evaluated in magnified images (Figure 8E and F), and infiltration of the bluish collagen gel into submucosal layer was observed with a characteristic undulating structure in the presence of NPB at 1.6 (Figure 8G). In contrast, collagen gels and submucosal layers (Figure 8F) were clearly distinguishable in the presence of NPB at 2 (Figure 8H).

Discussion

Applications of previous in situ gelling materials to EMR/ESD-derived artificial ulcers are hampered by poor TTS deliverability and/or failure of deposition on ulcer sites. Accordingly, several in situ gelling materials have been used to form weak physical gels as “lifting gels”,17 which create submucosal fluid cushions that facilitate EMR/ESD. However, these materials contain no crosslinkers for polymer–tissue and polymer–polymer connections, and therefore, they fail to form stabilized gel deposits on ulcers. Some tissue adhesives18 are also classified as in situ gelling materials and are prepared immediately before surgery by mixing polymer solution with crosslinking agent prior to injection through a syringe. Cross-linking agents then rapidly introduce polymer–tissue19 and polymer–polymer crosslinking20 and facilitate wound closure. However, rapid gelation without temperature responsiveness hampers TTS delivery. Thus, to overcome the two major technical obstacles for application of in situ gelling sols, the physiochemical properties of collagen–genipin sols were improved in a two-step gelation process involving collagen fibril formation and subsequent genipin-induced crosslinking.15

To this end, we initially increased the viscosity of collagen sols through condensation of collagen (Figure 1A), allowing retention of collagen sols on tilted ulcers before gelation and subsequent deposition of collagen gels on whole ulcers (Figure 7). In contrast to skin ulcers that are treated with plastic surgery, horizontal positions of gastrointestinal ulcers cannot be maintained during surgery, warranting the development of in situ gelling solutions that remain on tilted ulcers until gelation. However, increased viscosity hampered TTS deliverability (Figure 1C), and load–deformation curves (Figure 1B) suggested that delivery loads increase with the length of the catheter. Thus, the present 1.44% collagen sols, which had a viscosity of 6.6 Pa·s (at a shear rate of 1 s−1), were employed to simultaneously achieve higher viscosity and TTS deliverability.

Duration of sol fluidity is a critical property for TTS delivery. Accordingly, endoscopic use of an in situ gelling sol for the treatment of gastrointestinal ulcers is performed by preparing the sol, inserting the catheter into the endoscope channel, introducing the sol into the catheter, finely adjusting the endoscopic view, and positioning for delivery of the sol. The present 1.44% collagen sols containing genipin as a crosslinker retained sol fluidity at 23°C for >20 min (Figure 4), indicating appropriate properties for catheter delivery as an in situ gelling sol for the treatment of gastrointestinal ulcers.

Because delivered collagen sols are required to form gels immediately on contact with ulcers, we investigated gel formation of the 1.44% collagen sols on artificial ulcers at 37°C (Figure 8D–F). In these experiments, temperature responsiveness of gelation played a crucial role in gel deposition and increased with higher NPB concentrations (Figure 2B and C), allowing for thick gel deposition on tilted ulcers (Figure 9). In vivo, stomach generally has pH around 1.5–3.5, where collagen molecules lose the ability to form fibrils. When the 1.44% collagen sols are introduced into stomach in a living body, the high viscosity, rapid gelation, and subsequent stabilization by genipin-induced crosslinking would not allow for acidification of interior fluid prior to the gelation. These properties would also prevent the infiltration of pepsin. We are investigating gelation and biostability of the collagen sols and gels on stomach ulcers in vivo.

However, the use of concentrated NPB (2 × NPB) shortened gelation times at temperatures >23°C, potentially undermining TTS deliverability (Figure 4). Moreover, the endoscope and catheter may be warmed in the gastrointestinal tract during endoscopic observation and surgery and some time may be required between application and gelation of sols to allow for infiltration into submucosal layers (Figure 8G and H).

In the present study, genipin-induced crosslinking significantly improved the mechanical properties of collagen gels (Figures 3A and C and 6), indicating that deposition on ulcers may vary with genipin concentrations. Accordingly, the improved mechanical properties ensured stabilization of gels on ulcers, allowing for anchoring and infiltration of macro-fibers into submucosal layers. Moreover, increases in mechanical strength (eg, stresses at a strain of 0.3) were saturated at genipin concentrations of only 0.2–1 mM (Figure 6A–C), and animal cells remained viable in direct contact with genipin molecules at these concentrations in previous studies.21,22 Moreover, in the present gels, genipin molecules are incorporated into the in situ gel, thus minimizing the contact between genipin molecules and cells in the surrounding tissues. In general, the increase in the mechanical properties of collagenous materials by crosslinking reflects resistance to enzymatic degradation. It is expected that resistance to pepsin of the collagen gel could be improved and regulated by genipin concentrations.

As was previously reported for 0.5% collagen sol in 1 × NPB,14 genipin-induced crosslinking occurred gradually after plateauing of collagen fibril formation and was accelerated by increased NPB concentrations at this time point (Figure 3). In addition, genipin-induced crosslinking is temperature responsive, and gelation tests with pre-warmed genipin solutions showed enhanced crosslinking activity of genipin after incubation in NPB at 37°C (Figure 5D and E), possibly reflecting structural changes in genipin. In agreement, changes in the 13C NMR and UV spectra were analogous to those observed with genipin treated in a strong base,23 where ring-opening polymerization of genipin was proposed.24 Hence, similar polymerization of genipin likely occurs during gelation of collagen sols, providing a two-step gelation process involving collagen fibril formation and genipin-induced crosslinking of collagen.

Conclusion

We conclude that in situ gelling collagen–genipin sols have potential applications in the treatment of gastrointestinal ulcers. These sols were deliverable using TTS techniques and formed rigid gel depositions on tilted ulcers in response to body temperature. The present rheological, mechanical, and ex vivo data warrant future in vivo studies to demonstrate the efficacy of collagen–genipin sols in the treatment of gastrointestinal ulcers.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by a grant program “Adaptable and Seamless Technology Transfer Program through target driven R&D (A-STEP), Exploratory Research, Japan Science and Technology Agency”.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Ono H, Kondo H, Gotoda T, et al. Endoscopic mucosal resection for treatment of early gastric cancer. Gut. 2001;48(2):225–229. doi: 10.1136/gut.48.2.225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fujishiro M. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for stomach neoplasms. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12(32):5108–5112. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i32.5108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yamamoto H, Kita H. Endoscopic therapy of early gastric cancer. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;19(6):909–926. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2005.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim HS, Moon SJ, Youn HY, Lee MK, Lee JS. Management of the complications of endoscopic submucosal dissection. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17(31):3575–3579. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i31.3575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oda I, Suzuki H, Nonaka S, Yoshinaga S. Complications of gastric endoscopic submucosal dissection. Dig Endosc. 2013;25(1):71–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1443-1661.2012.01376.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matsuyama T, Aiko S, Yoshizumi Y, Sugiura Y, Maehara T. A case of esophageal stricture after corrosive esophagitis successfully treated by frequent endoscopic balloon dilation. Esophagus. 2004;1(4):193–197. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ronald VR, Goh L-K. Esophageal perforation: continuing challenge to treatment. Gastrointest Interv. 2013;2:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Qadeer AM, Dumot AJ, Vargo JJ, Lopez RA, Rice WT. Endoscopic clips for closing esophageal perforations: case report and pooled analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66(3):605–611. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2007.03.1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takizawa K, Oda I, Gotoda T, et al. Routine coagulation of visible vessels may prevent delayed bleeding after endoscopic submucosal dissection – an analysis of risk factors. Endoscopy. 2008;40(3):179–183. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-995530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ohki T, Yamamoto M, Ota M, Okano T, Yamamoto M. Application of cell sheet technology for esophageal endoscopic submucosal dissection. Tech Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;13(1):105–109. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kanai N, Yamato M, Ohki T, Yamamoto M, Okano T. Fabricated autologous epidermal cell sheets for the prevention of esophageal stricture after circumferential ESD in a porcine model. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;76(4):873–881. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2012.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim OH, Park KJ, Kim HJ, et al. Development of polyvinyl alcohol–sodium alginate gel-matrix-based wound dressing system containing nitrofurazone. Int J Pharm. 2008;359:79–86. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2008.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miguel PS, Ribeiroa PM, Brancala H, Coutinho P, Correia JI. Thermoresponsive chitosan–agarose hydrogel for skin regeneration. Carbohydr Polym. 2014;111:366–373. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2014.04.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yunoki S, Ohyabu Y, Hatayama H. Temperature-responsive gelation of type I collagen as solutions involving fibril formation and genipin cross-linking a potential injectable hydrogel. Int J Biomater. 2013;2013:14. doi: 10.1155/2013/620765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yunoki S, Hatayama H, Ebisawa M, Kondo E, Yasuda K. A novel fabrication method to create a thick collagen bundle composed of uniaxially aligned fibrils: an essential technology for the development of artificial tendon/ligament matrices. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2015;103A(9):3054–3065. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.35440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chambon F, Winter HH. Stopping of crosslinking reaction in a PDMS polymer at the gel point. Polym Bull. 1985;13:499–503. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yamamoto H, Yube T, Isoda N, et al. A novel method of endoscopic mucosal resection using sodium hyaluronate. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;50(2):251–256. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(99)70234-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Manabe T, Okino H, Tanaka M, Matsuda T. In situ-formed, tissue-adhesive co-gel composed of styrenated gelatin and styrenated antibody: potential use for local anti-cytokine antibody therapy on surgically resected tissues. Biomaterials. 2004;25(27):5867–5873. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kakinoki S, Taguchi T. Antitumor effect of an injectable in-situ forming drug delivery system composed of a novel tissue adhesive containing doxorubicin hydrochloride. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2007;67(3):676–681. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2007.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Straccia CM, Romano I, Oliva A, Santagata G, Laurienzo P. Crosslinker effects on functional properties of alginate/N-succinyl-chitosan based hydrogels. Carbohydr Polym. 2014;108:321–330. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2014.02.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mi L-F, Tan C-Y, Liang F-H, Sung W-H. In vivo biocompatibility and degradability of a novel injectable-chitosan-based implant. Biomaterials. 2002;23(1):181–191. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(01)00094-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen C-S, Wu C-Y, Mi L-F, Lin H-Y, Yu C-L, Sung W-H. A novel pH-sensitive hydrogel composed of N,O-carboxymethyl chitosan and alginate cross-linked by genipin for protein drug delivery. J Control Release. 2004;96(2):285–300. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2004.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mi L-F, Shyu S-S, Peng K-C. Characterization of ring-opening polymerization of genipin and pH-dependent cross-linking reactions between chitosan and genipin. J Polym Sci A. 2005;43:1985–2000. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mu C, Zhang K, Lin W, Li D. Ring-opening polymerization of genipin and its long-range crosslinking effect on collagen hydrogel. J Biomed Mater Res. 2013;101(2):385–393. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.34338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]