Abstract

Recent work on triazabutadienes has shown that they possess the ability to release aryl diazonium ions under exceptionally mild acidic conditions. There are instances that require that this release be prevented or minimized. Accordingly, a base-labile protection strategy for the triazabutadiene is presented allowing for enhanced synthetic and practical utility of the triazabutadiene. Herein the effects of steric and electronic factors in the rate of removal are discussed. Finally, the triazabutadiene protection is shown to be compatible with the traditional acid-labile protection strategy used in solid phase peptide synthesis.

Keywords: protecting group, aryl diazonium ion, rate of hydrolysis, acid / base chemistry

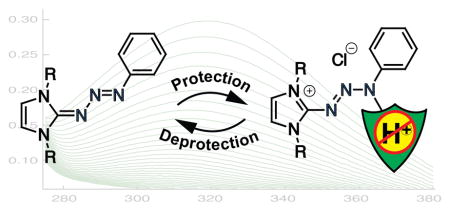

Graphical Abstract

Triazabutadienes can be used as masked tyrosine-selective aryl diazonium ions. We report a base-labile protecting group for triazabutadienes to prevent the acid-dependent release of aryl diazonium ions. The pH-dependent deprotection rate constants are reported with electronic and steric perturbations to the system, enabling widespread utility of triazabutadienes in chemical biology.

Chemical reactions that proceed with predictable outcomes in aqueous media are of interest to the field of bioconjugation. Selectivity is both essential and challenging as sample complexity increases. The selective reactivity of aryl diazonium ions with protein side chains has been known for over 100 years,[1] but yet their utility remains untapped relative to the thiol and amine-selective counterparts.[2] A likely culprit for the dearth of literature is the fleeting nature of the aryl diazonium ion. Expulsion of nitrogen gas to produce an aryl cation occurs rapidly compared with the timescales involved with manipulation and purification of proteins.[3] We recently reported a protecting group for aryl diazonium ions, called triazabutadienes, that can be liberated under physiological pH.[4] The mild release of the aryl diazonium was highly encouraging, but the reaction suffered from a non-zero release rate at pH 7.4. While we found that the reaction could be accelerated with light,[5] we have thus far been unsuccessful in attempts to tune the triazabutadiene electronically or with steric bulk to maintain fast cleavage at pH 5–6, but stability at pH 7.[6] Herein we report a strategy to protect, or shield, triazabutadienes to prevent aryl diazonium release under acidic conditions.

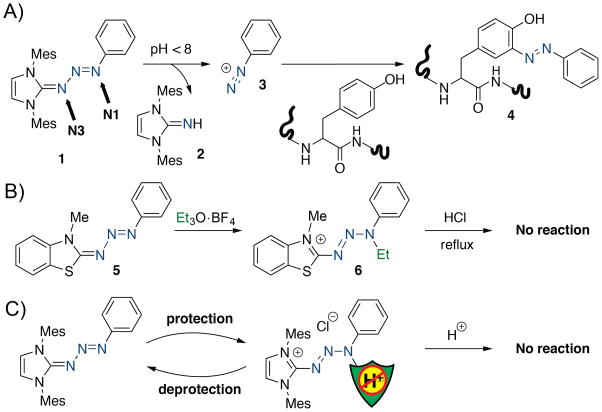

Triazabutadienes (1,[7] Scheme 1a) are an interesting functional group insofar as they possess two competing basic nitrogen atoms. The N1 nitrogen atom, closer to the aryl ring, is more basic, but protonation at N1 does not provide a productive reaction pathway to break apart the triazabutadienes.[8] Protonation at the less basic N3 nitrogen atom of 1 rapidly provides guanidine 2 and benzene diazonium ion (3), which can go on to form azobenzene adducts with tyrosine (4). Protonation, or alkylation, at N1 prevents a second protonation event occurring at N3. Fanghänel, who established much of the fundamental reactivity of triazabutadienes, noted that triazabutadiene 5 could be alkylated at N1 with ethyl Meerwein’s reagent to provide a salt (6) that was recalcitrant to acidic reaction, even refluxing hydrochloric acid (Scheme 1b).[9] While promising toward our goal of acid protection, this modification looks to be irreversible; we require reversibility (Scheme 1c). We hypothesized that installation of a carbonyl would provide protection against acids and would be removable under conditions of basic hydrolysis. It was not clear at the outset if these compounds would be possible to synthesize, or stable under physiological conditions.

Scheme 1.

a) Triazabutadienes (such as 1) protonate at N3 and react to produce imidazole imines (2) and liberate aryl diazonium ions (3). These aryl diazonium ions can go on to react with tyrosine side chains to form azobenzene products (4). b) Previous work by Fanghänel showed that 5 can be alkylated to provide 6, which is stable to acid. c) We report herein a reversible protecting group for triazabutadienes that prevents aryl diazonium release. Me = methyl, Et = ethyl, Mes = 2,4,6-trimethylbenzenyl.

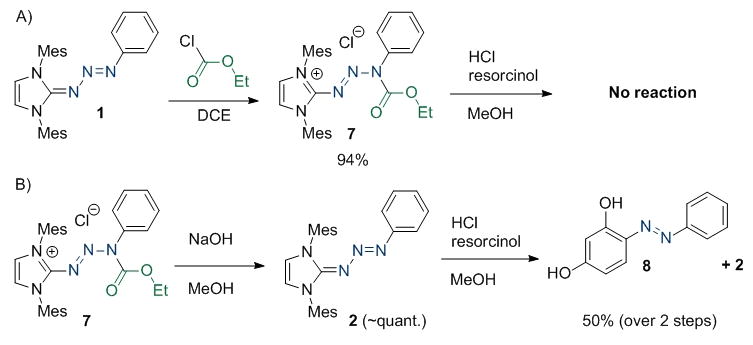

In the event, triazabutadiene 1 was treated with ethyl chloroformate to provide protected triazabutadiene 7 (Scheme 2a). The salt was stable at ambient temperature[10] and could be readily synthesized and characterized. Upon dissolution in methanolic hydrochloric acid we observed that the compound was indeed stable for prolonged times. Treatment with sodium hydroxide cleanly provided the starting triazabutadiene, 1 (Scheme 2b). When the solution was subsequently acidified, 1 went on to release a benzenediazonium salt that was trapped in situ by resorcinol to provide Sudan Orange G (8). The high degree of stability of triazabutadienes to basic conditions makes them especially well suited to these deprotection conditions. Well aware that methanol and water are not comparable, we focused the remainder of our studies on the hydrolytic stability in buffered aqueous solutions.

Scheme 2.

a) Synthesis and reactivity of protected triazabutadiene 7. b) The protection can be hydrolysed from 7 under basic conditions to return acid sensitive 1 (where aryl diazonium 3 is trapped as 8).

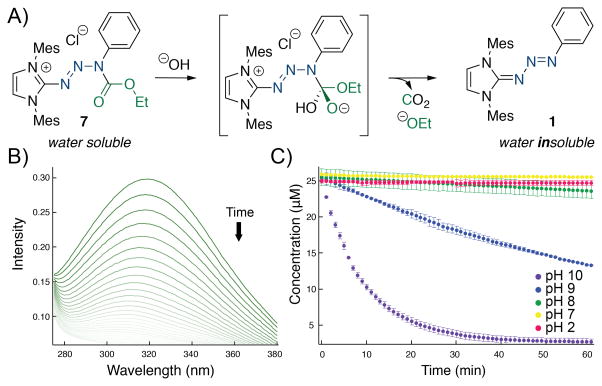

We theorize that the reaction to deprotect 7 follows a BAC2 pathway (Figure 1a). Protected triazabutadiene 7 was mildly soluble in water; sufficiently soluble to determine the reaction kinetics using UV/Vis (Figure 1b, see Supporting information FIgure S1). While 7 is soluble, the resulting triazabutadiene, 1, is almost completely insoluble. This difference in solubility made following the progress of the deprotection reactions straightforward for 7. The reactions were initially followed at constant pH using buffers. Looking at pH 9 and 10, they appeared to follow simple second order kinetics with respect to concentration of hydroxide (Figure 1c). Compound 7 was shown to be highly stable at pH 7, and even at pH 8 the extrapolated half-life is on the order of a day. As was true with acidic methanol experiment (Scheme 2a) there was no degradation observed at pH 2. To test the rate under pseudo first order conditions, reactions were run from pH 10.0 to 10.8 and the rate was found to be 13.5 ± 1.5 M−1s−1.[11] Concerned about possible redox reactivity with thiols, 7 was incubated with 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol in pH 7 buffer. No thiol-dependent reactivity was observed over the course of the 2-hour experiment.

Figure 1.

a) Proposed BAC2 mechanism of deprotection of 7 to provide 1. b) The disappearance of 7 is monitored by UV/vis to provide kinetics curves c). Compound 7 is deprotected in a pH dependant manner.

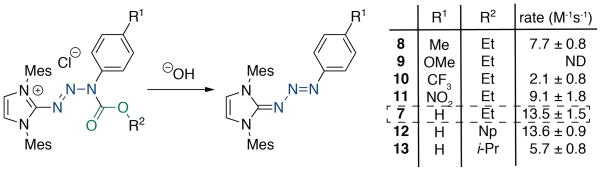

To better understand the influences of the reactivity of this new protecting group, we synthesized several protected triazabutadienes that had varying electronic properties on the aryl ring (Figure 2). All of the protected triazabutadienes have similar λmax values (~320 nm) that have a hypsochromic shift from the fully conjugated triazabutadiene precursors. This similarity of λmax is in stark contrast to the non-protected triazabutadienes that can vary dramatically in their UV/Vis spectra. Armed with this spectral data we hypothesized, incorrectly, that the conjugation in the system had been perturbed enough that the changes in aryl ring electronics were not going to affect the rate of deprotection. In the event, the inductively electron donating p-methyl substituent, 8, slowed the rate of deprotection moderately (Figure 2). This can be rationalized by a model whereby the carbonyl is stabilized by being more electron-rich and thusly less prone to nucleophilic attack. The strongly resonance donating p-methoxy substituted compound, 9, further slowed the rate of hydrolysis, so much so that the rate could not be accurately determined due to the error of the analytical technique. Interestingly, both of the electron-withdrawing compounds that we analyzed, p-trifluoromethyl 10 and p-nitro 11, slowed the hydrolysis as well. We observed an inverted trend of resonance and inductive effects on the rates with the withdrawing groups. Inductively withdrawing p-trifluoromethyl 10 slowed hydrolysis considerably compared with the strongly resonance withdrawing p-nitro substituted 11. The root cause of this stabilization is not understood at this time, but as a protecting strategy we were relieved that modifications on the ring appear to stabilize regardless of their nature.

Figure 2.

Rates of basic hydrolysis of several protected triazabutadienes showed that aryl substitutions (R1) slow the rate of hydrolysis, as does steric hindrance adjacent to the reactive carbonyl. Np = neopentyl, i-Pr = i-propyl.

Owing to our proposed mechanism for hydrolysis wherein a nucleophile must approach the carbonyl π* we expected there to be a rate-dependence on the size of alkyl group appended to the carbamate. This effect was expected to be somewhat tempered by the additional oxygen atom that moves any steric perturbation further away. In the event we observed only a small change in rate moving from ethyl 7, to neopentyl 12 and i-propyl 13, but from a protecting group strategy perspective these differences in rate are relatively small (Figure 2). We were unable to synthesize the protected traizabutadiene from t-butyl chloroformate, presumably due to it being overly hindered.

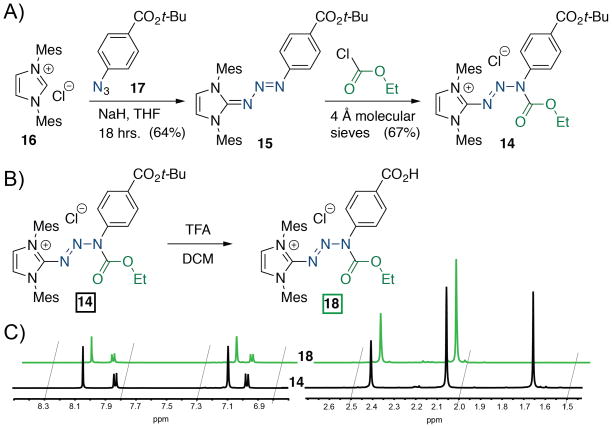

In addition to rendering the triazabutadiene moiety more compatible with protein bioconjugation strategies, the acid-stability makes the triazabutadiene compatible with most traditional Boc-strategies of solid-phase peptide synthesis.[12] To challenge this assertion we synthesized protected triazabutadiene 14 bearing a t-butyl ester (Figure 3a). The precursor, triazabutadiene 15, was synthesized from the reaction of an in situ generated N-heterocyclic carbene from deprotonating 16 and aryl azide 17. Protection with ethyl chloroformate proceeded as before to provide 14. The acid-labile t-butyl ester was removed using trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) in dichloromethane to garner 18 (Figure 3b & c). Under the same reaction conditions the non-protected triazabutadiene readily releases an aryl diazonium ion. This advance will allow us, and others, to synthesize peptides that contain a latent aryl diazonium ion that could be used in experiments ranging from receptor-target identification to appending chemical cargos via azobenzene linkages.

Figure 3.

a) Triazabutadiene 14, containing a t-butyl ester was synthesized in 2 steps from azide 17. b) The acid-labile ester, 14, was hydrolysed to 18 under strongly acidic conditions. c) Crude NMR (in methanol-d4) of the reaction from 14 to 18 shows the efficiency of this reaction.

We have presented a new protecting group strategy for triazabutadienes, a functionality that can in turn be viewed as protecting groups for aryl diazonium ions. These protected triazabutadiene compounds are operationally easy to synthesize and should find general utility amongst those seeking to expand the power of masked aryl diazonium species. This work removes one of the few remaining liabilities that we have observed concerning the chemical reactivity of the triazabutadiene scaffold and we look forward to the new avenues that this chemistry affords chemists broadly speaking.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Katrina Miranda and Elisa Tomat for use of their instruments. This work was supported in part by a NSF-CAREER award to JCJ (CHE-1552568). LEG received support from IMSD/NIH fellowship (R25 GM062584) & NIH Training Grant (T32 GM008804). We also thank the NSF for a departmental instrumentation grant for the NMR facility (CHE-0840336).

Footnotes

Supporting information for this article is given via a link at the end of the document.

References

- 1.a) Pauly H. Hoppe-Seyler’s Z Physiol Chem. 1915;94:284–290. [Google Scholar]; b) Higgins HG, Fraser D. Aust J Chem. 1952;5:736–753. [Google Scholar]; c) Tracey BM, Shuker DEG. Chem Res Toxicol. 1997;10:1378–1386. doi: 10.1021/tx970117+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Schlick TL, Ding Z, Kovacs EW, Francis MB. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:3718–3723. doi: 10.1021/ja046239n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Jones MW, Mantovani G, Blindauer CA, Ryan SM, Wang X, Brayden DJ, Haddleton DM. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:7406–7413. doi: 10.1021/ja211855q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stephanopoulos N, Francis MB. Nat Chem Biol. 2011;7:876–884. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.a) Patai S. The Chemistry of Diazonium and Diazo Groups. 1978. [Google Scholar]; b) Hegarty AF. In: The Chemistry of Diazonium and Diazo Groups. Patai S, editor. Vol. 2. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; New York, NY: 1978. pp. 511–591. [Google Scholar]

- 4.a) Kimani FW, Jewett JC. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2015;54:4051–4054. doi: 10.1002/anie.201411277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Patil S, Bugarin A. Eur J Org Chem. 2016:860–870. [Google Scholar]

- 5.He J, Kimani FW, Jewett JC. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:9764–9767. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b04367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.In fact, to the best of our knowledge that type of reactivity is unprecedented for small molecules.

- 7.Tennyson AG, Moorhead EJ, Madison BL, Er JAV, Lynch VM, Bielawski CW. Eur J Org Chem. 2010:6277–6282. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fanghänel E, Hohlfeld J. J Prakt Chem. 1981;323:253–261. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fanghänel E, Poleschner H, Radeglia R, Hänsel R. J Prakt Chem. 1977;319:813–826. [Google Scholar]

- 10.After 3 months at room temperature NMR analysis of the sample a 1:1 mixture of the protected and deprotected forms.

- 11.When ionic strength was changed by the addition of sodium chloride there was no/minimal effect on the rate at pH 10.2.

- 12.Nucleophilic bases, such as piperidine, were found to remove the protection.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.