Abstract

WRKY transcription factors play important roles in plant development and stress responses. Here, global expression patterns of pepper CaWRKYs in various tissues as well as response to environmental stresses and plant hormones were systematically analyzed, with an emphasis on fruit ripening. The results showed that most CaWRKYs were expressed in at least two of the tissues tested. Group I, a subfamily of the entire CaWRKY gene family, had a higher expression level in vegetative tissues, whereas groups IIa and III showed relatively lower expression levels. Comparative analysis showed that the constitutively highly expressed WRKY genes were conserved in tomato and pepper, suggesting potential functional similarities. Among the identified 61 CaWRKYs, almost 60% were expressed during pepper fruit maturation, and the group I genes were in higher proportion during the ripening process, indicating an as-yet unknown function of group I in the fruit maturation process. Further analysis suggested that many CaWRKYs expressed during fruit ripening were also regulated by abiotic stresses or plant hormones, indicating that these CaWRKYs play roles in the stress-related signaling pathways during fruit ripening. This study provides new insights to the current research on CaWRKY and contributes to our knowledge about the global regulatory network in pepper fruit ripening.

Complex and concerted biological processes such as plant growth and development are regulated by various internal and external environmental signals. Transcription factors play an important part in these signaling pathways1,2. As one of the largest transcription factor families in higher plants, WRKY have been shown to be involved in a multitude of biological processes, including stress response and physiological progress. The common feature of WRKY proteins is the highly conserved N-terminal WRKY domain, which includes an almost conservative peptide (WRKYGQK) and a zinc-finger structure (Cx4–5Cx22–23HxH or Cx7Cx23HxC)3. The WRKY domain consists of a four-stranded β-sheet and a zinc-binding pocket. It is now known to be the critical structure for DNA binding4, which helps to activate or repress the transcription of downstream target regions and regulates the relevant physiological processes.

Since its first identification in sweet potato5,6, WRKY has been characterized in various plant species and shown to be involved in many biological processes, including biotic and abiotic stress responses7,8,9 and plant–pathogen interactions9,10. In tomato, the effector-triggered immunity against Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato strain DC3000 (PstDC3000) depends on the expression of SlPR1 and SlPR1a1 induced by SlWRKY3911. SlWRKY12 positively regulates resistance to Botrytis cinerea8. In pepper, CaWRKY40 was proved to be involved in the modulation of both high temperature tolerance and Ralstonia solanacearum resistance, and this regulation seems to depend on the transcriptional activation of CaWRKY069, which is a classical feedback regulation mode of WRKY proteins. In addition, WRKY proteins also play an important role in plant growth and development, such as plant hormone signaling7,12, secondary signal metabolism13,14, trichome and seed development15,16, germination17 and leaf senescence18,19.

As a highly conserved protein family reflected by both conservative WRKY-domain and specific W-box (TTGACC/T) recognition, the diverse regulating function of WRKY is partly due to its interaction with other proteins that forms a complex signal transduction pathway20. In Arabidopsis, AtWRKY25 and AtWRKY33 interact with AtMKS1 (substrate of AtMPK4) to form a complex, which is subsequently involved in the plant defense response21,22. Known to regulate endosperm growth and seed size, AtIKU1 also interacts with AtWRKY1023. Recent studies showed that a newly identified VQ-motif protein family is one of the most important WRKY interacting proteins, some WRKY and VQ proteins sometimes work together to regulate biological processes20. At present, the majority of identified WRKYs are from model plants, such as Arabidopsis and rice24,25.

Klee and Giovannoni26 classified fleshy fruits into two physiological types—climacteric (tomato and banana) and non-climacteric (pepper and strawberry). Thus, pepper and tomato present suitable models for highlighting the different types of fruit ripening processes. In the past, little focus was placed on the fruit maturing process of pepper, a non-climacteric fruit, as compared to the climacteric fruit tomato. As a critical stage for pepper yield and quality (size, weight, color, nutrient), fruit ripening can also be affected by many internal and external factors such as hormone signals and biotic or abiotic stresses11,27,28. Transcription factors are also important for fruit ripening29,30. Recently, different types of transcription factors, including WRKY, MYB, and AP2/EREBP, have been induced during the ripening of pepper fruits31. Several CaWRKYs have also been reported to be involved in stress responses in pepper9,10,32. However, there are a very few studies on the potential roles of CaWRKY proteins in fruit maturation. The recent elucidation of the whole pepper genome sequence33,34 (http://peppersequence.genomics.cn/;http://pgd.pepper.snu.ac.kr) will be an asset in deciphering expression patterns and potential functions of all CaWRKY transcription factors during the process of pepper fruit maturation.

Although a comprehensive study of CaWRKYs in pepper was recently performed35, little focus was placed on comprehensive expression profiles of the entire WRKY gene family in tissues and their response to abiotic stresses. The global analysis of the CaWRKY gene expression pattern will facilitate the functional studies of pepper CaWRKYs. We identified 61 CaWRKYs and analyzed the expression profiles of all the members in various tissues using RNA-seq and quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR), with emphasis on fruit maturation. Furthermore, comprehensive analysis of the expression patterns of the whole CaWRKY gene family under different stress conditions (high salinity, drought, and heat) and in the presence of phytohormones (salicylic acid [SA], jasmonic acid [JA], abscisic acid [ABA] and brassinolide [BR]) revealed the critical and complex regulating roles of CaWRKYs in pepper fruit maturation at the transcriptional level.

Results

Classification and expression profile analysis of pepper CaWRKY genes

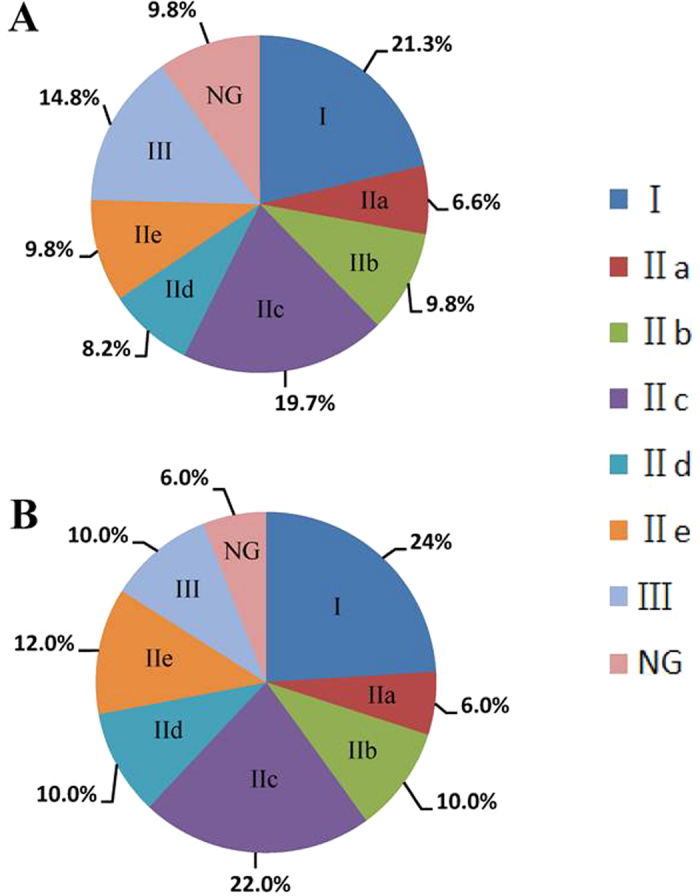

A total of 61 potential CaWRKYs were identified in the pepper genome (Supplemental Table S1). Based on the number and structure of WRKY domains, 55 of the CaWRKY proteins were classified into three main groups: group I, group II (IIa, IIb, IIc, IId, and IIe), and group III (Supplemental Figure S1; Supplemental Table S2). Two of the CaWRKYs (CaWRKY01 and CaWRKY12) were excluded from phylogenetic analysis as their WRKY domains were incomplete (Supplemental Table S3). The remaining four CaWRKYs (CaWRKY17, CaWRKY19, CaWRKY46, and CaWRKY52) showed evolutionary uniqueness (Supplemental Figure S1) and were not assigned to any group. Thus, all these genes were defined as None-group (NG) in the study. As shown in Fig. 1A, the group II (including IIa, IIb, IIc, IId, and IIe) members had a higher proportion of proteins (54.1%) than did the other groups (I, III and NG). Of the five subgroups within group II, group IIc had the highest proportion of proteins (19.7%), whereas group IIa had the lowest (6.6%).

Figure 1. Subfamily constitution of pepper CaWRKYs.

(A) Group constitution of the identified pepper CaWRKYs. (B) CaWRKY genes expressed in the investigated plant tissues. A signal intensity level of over 5.0 is considered to be expressed in the given tissue. 50 of the 61 CaWRKYs are expressed in at least one tested tissue. Percentages of CaWRKY groups are demonstrated in the figure.

Using the RNA-seq data of different pepper tissues (root, stem, leaf, bud, flower, and fruit) published previously33, we found that 50 CaWRKY genes were expressed in at least one tissue (reads per kilobase exon model per million mapped reads [RPKM] ≥5.0 was defined as expressed) (Supplemental Table S4). The highest expression level (RPKM = 487.77) was detected for CaWRKY28 in leaf. As shown in Fig. 1B, the group II members comprised up to 60% and the group I members 24% of all the 50 expressed CaWRKYs. Comparative analysis found that the percentage of WRKYs expressed in group I and group II was higher than that in the remaining two groups (Fig. 1A,B), indicating their higher activity. Among the remaining non-expressed CaWRKY genes, 7 out of 11 were derived from group III (CaWRKY05, CaWRKY29, CaWRKY32 and CaWRKY49) and NG (CaWRKY17, CaWRKY19 and CaWRKY46) (Supplemental Tables S2 and S4). Meanwhile, all members of group IId and group IIe CaWRKYs were expressed in at least one of the tissues examined (Supplemental Tables S2 and S4).

CaWRKY gene expression in different tissues

To compare in detail the CaWRKY expression in different tissues, the RNA-seq data of the 61 CaWRKY genes were selected for further analysis33. CaWRKY genes with RPKM value ≥5.0 were defined as expressed genes in the specific tissue. The genes expressed only in one tissue were considered to be specifically expressed CaWRKYs, and those with the highest expression in specific tissue were regarded as preferentially expressed. According to Table 1, the number of both expressed and preferentially expressed CaWRKYs in vegetative tissue (root, stem, and leaf) was higher than that in reproductive tissue (bud, flower, and fruit). Only one or two specifically expressed CaWRKY genes were identified in each tested tissue. As shown in Fig. 2A and supplemental Table S4, the expression of some CaWRKY genes was tissue specific, such as that of CaWRKY09 (RPKM = 11.21) and CaWRKY26 (RPKM = 20.26) that were only expressed in the root, CaWRKY04 (RPKM = 20.71) that was expressed in the stem, CaWRKY40 (RPKM = 8.82) and CaWRKY56 (RPKM = 17.18) that were expressed in the leaf, CaWRKY01 (RPKM = 31.42) that was expressed in the fully ripened fruit, and CaWRKY25 (RPKM = 480.15) that was expressed in floral parts. However, most CaWRKYs were expressed in two or more tissues. Furthermore, compared to reproductive organs (flower and fruit), the number of preferentially expressed CaWRKYs was higher in vegetative parts.

Table 1. The number of expressed, preferentially expressed, and specifically expressed CaWRKY genes in different tissues.

| Type | Root | Stem | Leaf | Bud | Flower | Fruit-Dev5 | Fruit-Dev6 | Fruit-Dev7 | Fruit-Dev8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Expressed CaWRKYs | 40 | 37 | 40 | 23 | 34 | 20 | 21 | 21 | 23 |

| Preferentially expressed CaWRKYs | 15 | 7 | 17 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Specifically expressed CaWRKYs | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

Figure 2.

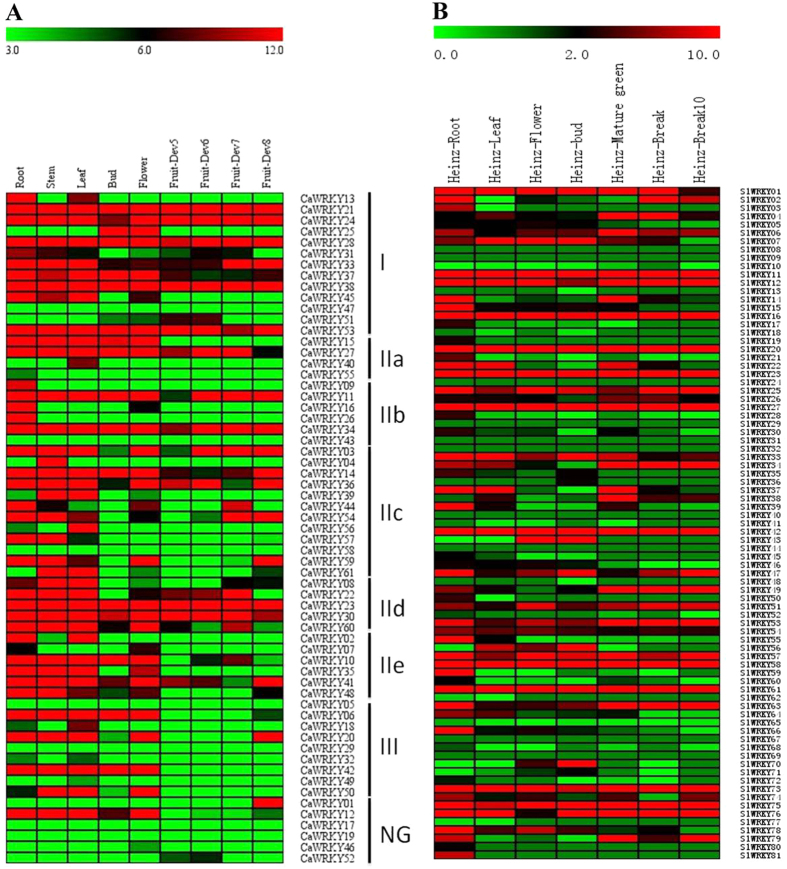

Cluster analysis of tissue-specific expression profiles of pepper (A) and tomato (B) WRKY genes. WRKY gene expression was obtained from the RNA-seq data. WRKY genes and various tissues are represented as rows and columns. Green, black, and red elements indicate low, regular, and high signal intensity, respectively. Cluster analysis was performed based on expression profiles of 61 CaWRKYs (A) and 81 SlWRKYs (B) in various tissues (root, stem, leaf, flower, and fruit). CaWRKYs that belong to the same group are clustered together for a more intuitive analysis.

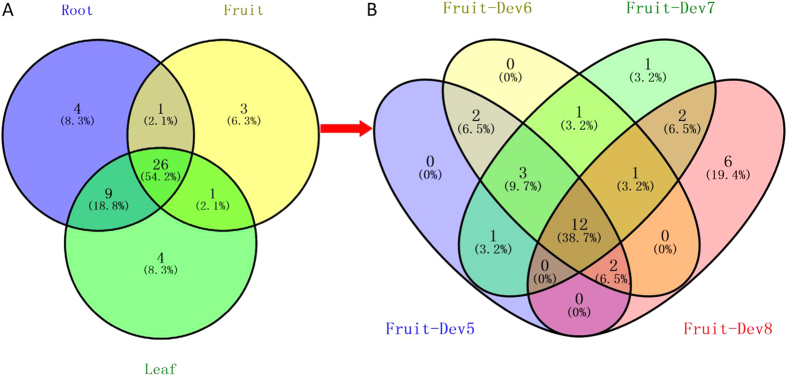

Based on the CaWRKY expression profiles in various tissues (root, leaf, fruit) and different stages of fruit development (Fig. 3), we found that more than half (54.2%) of CaWRKYs were simultaneously expressed in the root, leaf, and fruit. Moreover, root and leaf possess many common CaWRKYs (Fig. 3A). Further analysis suggested that nearly 40% of CaWRKYs were always expressed during the process of fruit ripening (Dev5 to Dev8), and 19.4% of CaWRKYs seem to be expressed only at the late stage of fruit maturation (Dev8) (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3. Number of expressed CaWRKYs in different tissues.

The interaction of vegetative tissues (roots and leaves) and reproductive tissue (fruits) (A) and the number of expressed CaWRKYs in different fruit developmental stages (Dev5, Dev6, Dev7, Dev8) (B).

Further analysis of the expression profiles in various tissues revealed that, although group I members possess only 24% of the detected expressed CaWRKYs (Fig. 1), the percentage of group I members in reproductive tissues (bud, flower and fruit) and especially in fruits at the early mature stages, was significantly higher (~42%) (Table 2), suggesting the potentially important role of group I CaWRKYs during fruit ripening. The subgroup IId presented a similar situation (Table 2). In contrast, although group III contained 10.0% of all expressed CaWRKYs, the members of this group were barely detected in fruits. The expression profiles of other groups and subgroups varied among different tissues. For example, the proportion of expressed CaWRKYs from subgroups IIa and IIb were well distributed in all the tissues tested, and group IIc had the lowest percentage in the bud (Table 2).

Table 2. Subfamily constitution of expressed CaWRKY genes in different tissues of pepper plants.

| Type | Root | % | Stem | % | Leaf | % | Bud | % | Flower | % | Fruit | Total | % | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dev5 | % | Dev6 | % | Dev7 | % | Dev8 | % | |||||||||||||

| I | 10 | 25.6 | 9 | 24.3 | 10 | 24.4 | 8 | 33.3 | 9 | 26.5 | 9 | 45.0 | 9 | 42.9 | 8 | 38.1 | 7 | 29.2 | 12 | 23.5 |

| IIa | 2 | 5.1 | 2 | 5.5 | 3 | 7.3 | 2 | 8.3 | 2 | 5.9 | 1 | 5.0 | 1 | 4.8 | 1 | 4.8 | 1 | 4.2 | 3 | 5.9 |

| IIb | 5 | 12.8 | 2 | 5.4 | 2 | 4.9 | 2 | 8.3 | 3 | 8.8 | 2 | 10.0 | 2 | 9.5 | 2 | 9.5 | 2 | 8.3 | 5 | 9.8 |

| IIc | 7 | 17.9 | 10 | 27.0 | 9 | 22.0 | 2 | 8.3 | 6 | 17.6 | 2 | 10.0 | 3 | 14.3 | 4 | 19.5 | 6 | 25.0 | 11 | 21.6 |

| IId | 5 | 12.8 | 5 | 13.5 | 5 | 12.2 | 3 | 12.5 | 4 | 11.8 | 4 | 20.0 | 3 | 14.3 | 5 | 23.8 | 3 | 12.5 | 5 | 9.8 |

| IIe | 5 | 12.8 | 4 | 10.8 | 5 | 12.2 | 4 | 16.7 | 5 | 14.7 | 1 | 5.0 | 2 | 9.5 | 1 | 4.8 | 2 | 8.3 | 6 | 11.8 |

| III | 4 | 10.3 | 4 | 10.8 | 6 | 14.6 | 2 | 8.3 | 4 | 11.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 8.3 | 6 | 11.8 |

| NG | 1 | 2.6 | 1 | 2.7 | 1 | 2.4 | 1 | 4.2 | 1 | 2.9 | 1 | 5.0 | 1 | 4.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 4.2 | 3 | 5.9 |

| Total | 39 | 100 | 37 | 100 | 41 | 100 | 24 | 100 | 34 | 100 | 20 | 100 | 21 | 100 | 21 | 100 | 24 | 100 | 54 | 100 |

NG: None-group, genes that were not assigned to any group; Dev 5: Mature green, the full size green fruit (5–6 cm); Dev6: Breaker, fruit turning red; Dev7: Breaker plus 3days; Dev8: Breaker plus 5 days.

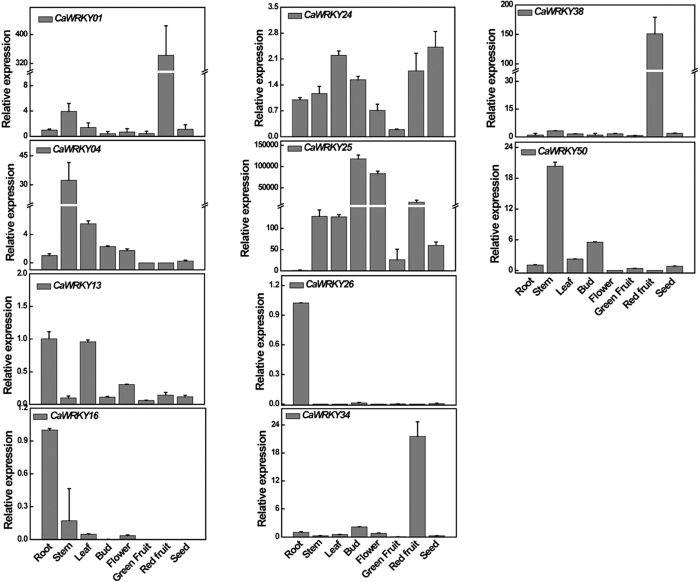

In order to confirm the reliability of RNA-seq data, qPCR was used to test and verify the expression of CaWRKY genes in nine specific tissues (root, stem, leaf, bud, flower, green fruit, red fruit, and seed) of the pepper commercial F1 hybrid Zhejiao-3. Ten CaWRKY genes with tissue-specific expression patterns were selected for comparison. The results obtained were consistent with the RNA-seq data (Figs 2 and 4), proving the reliability of the RNA-seq data33 (http://peppersequence.genomics.cn).

Figure 4. Expression of 12 CaWRKY genes in various tissues.

The expression levels of these CaWRKYs in various tissues (root, stem, leaf, bud, flower, green fruit, red fruit, and seed) were tested using qPCR and the results showed high consistence with the RNA-seq data.

Conserved constitutive highly expressed CaWRKYs in pepper and tomato

Of all the expressed CaWRKYs, 16 were highly expressed and found abundantly in each tissue. These were identified (Supplemental Table S4) as group I (5), group II (10) and NG (1) and defined as conserved, constitutively highly expressed CaWRKYs (Table 3). The expression levels of these CaWRKY genes in most tested tissues were significantly higher than the basic RPKM value (5.0), some of which reaching up to 500 (CaWRKY28 in leaf, RPKM = 487.77). With the average expression level of 185.97 among all the tested tissues, CaWRKY28, a member of group I, had the highest expression in almost every tissue (Supplemental Table S4).

Table 3. Constitutively highly expressed CaWRKYs in pepper, tomato, and potato.

| Name | Locus no. | Type | Name | Locus no. | Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CaWRKY28 | Capana06g001506 | I | SlWRKY11 | solyc07g066220.2.1 | I |

| CaWRKY53 | Capana11g001882 | I | SlWRKY12 | solyc06g066370.2.1 | I |

| CaWRKY38 | Capana07g002454 | I | SlWRKY01 | solyc12g014610.1.1 | I |

| CaWRKY21 | Capana03g003085 | I | SlWRKY61 | solyc07g065260.2.1 | I |

| CaWRKY24 | Capana04g001820 | I | SlWRKY27 | solyc03g104810.2.1 | I |

| CaWRKY27 | Capana06g001110 | IIa | SlWRKY47 | solyc05g012770.2.1 | I |

| CaWRKY11 | Capana02g002230 | IIb | SlWRKY75 | solyc12g006170.1.1 | I |

| CaWRKY34 | Capana07g001387 | IIb | SlWRKY06 | solyc07g047960.2.1 | I |

| CaWRKY03 | Capana01g002803 | IIc | SlWRKY51 | solyc07g005650.2.1 | I |

| CaWRKY36 | Capana07g001968 | IIc | SlWRKY73 | solyc06g068460.2.1 | IIa |

| CaWRKY23 | Capana04g000568 | IId | SlWRKY25 | solyc07g051840.2.1 | IIb |

| CaWRKY60 | Capana00g003083 | IId | SlWRKY74 | solyc02g080890.2.1 | IIb |

| CaWRKY30 | Capana06g003072 | IId | SlWRKY33 | solyc02g093050.2.1 | IIc |

| CaWRKY41 | Capana08g001012 | IIe | SlWRKY20 | solyc02g088340.2.1 | IIc |

| CaWRKY10 | Capana02g001642 | IIe | SlWRKY63 | solyc01g079260.2.1 | IIc |

| CaWRKY12 | Capana02g003053 | NG | SlWRKY53 | solyc05g012500.2.1 | IIc |

| SlWRKY42 | solyc08g006320.2.1 | IId | |||

| SlWRKY58 | solyc04g078550.2.1 | IId | |||

| SlWRKY78 | solyc07g055280.2.1 | IId | |||

| SlWRKY57 | solyc06g008610.2.1 | IId | |||

| SlWRKY15 | solyc09g066010.1.1 | IId | |||

| SlWRKY07 | solyc01g079360.2.1 | IId | |||

| SlWRKY16 | solyc01g095630.2.1 | III | |||

| SlWRKY76 | solyc03g095770.2.1 | III | |||

| SlWRKY23 | solyc09g015770.2.1 | III | |||

| SlWRKY54 | solyc05g050330.2.1 | III |

NG: None-group, genes that were not assigned to any group.

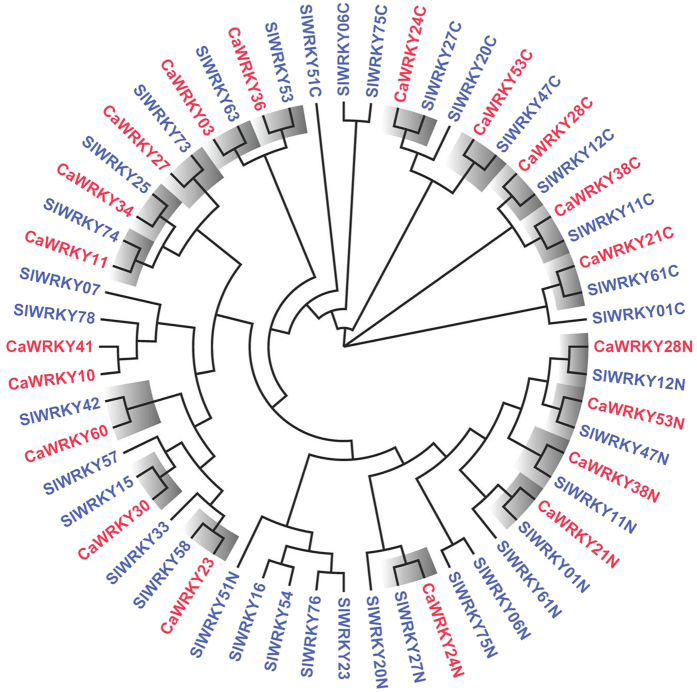

Additionally, 26 out of 81 constitutively highly expressed tomato WRKYs (SlWRKYs) from various tissues (root, leaf, bud, flower and fruit) were identified (Fig. 2B; Table 3; Supplemental Table S4). Phylogenetic analyses of 16 and 26 SlWRKYs constitutively highly expressed in pepper and tomato, respectively, revealed 14 pairs of orthologous genes (Fig. 5), implying their potential functional conservation. The results showed that, in addition to the resemblance in group constitution between pepper and tomato (Table 3), some SlWRKY members were also evolutionarily conservative with genes of pepper. For example, pepper CaWRKY28 and tomato SlWRKY12 were both constitutively highly expressed in various tissues as orthologous proteins. The similar phenomenon was also observed in many other conserved highly expressed WRKY pairs (Fig. 5; Table 3), indicating that the basic expression pattern of WRKY transcription factors might have been formed before the differentiation of Solanaceae plants and that they performed conservative and basic functions in plant growth and development.

Figure 5. Phylogenetic analysis of constitutively highly expressed WRKYs in tomato and pepper.

The orthologous genes between tomato and pepper are highlighted in gray.

Preferentially and specifically expressed CaWRKY genes during pepper fruit ripening

According to the expression standard (RPKM ≥5.0), 31 CaWRKY genes were expressed during fruit maturation and the highest expression level (RPKM = 200.28) was detected for CaWRKY28 in the late maturation stage of the fruit (Dev8: 5th day after breaker). Among the 31 CaWRKY genes, four of them were preferentially expressed at Dev6 (breaker), Dev7 (3rd day after breaker) and Dev8, while only one of the specifically expressed CaWRKY was detected in the late maturation stage of the fruit (Dev8) (Table 1; Supplemental Table S4). The five preferentially or specifically expressed CaWRKYs belong to group I (CaWRKY24 in Fruit-Dev7, RPKM = 58.45; CaWRKY51 in Fruit-Dev6, RPKM = 7.82), group IIb (CaWRKY11 in Fruit-Dev8, RPKM = 171.69), and NG (CaWRKY01 in Fruit-Dev8, RPKM = 31.42; CaWRKY52 in Fruit-Dev6, RPKM = 5.57) (Table 1; Supplemental TableS4). The analysis of the average expression level of CaWRKYs suggested that the 31 CaWRKYs expressed in fruit are globally induced during the fruit ripening process. The average expression level of group IIb was dramatically increased from 7.24 (Dev5: mature green stage) to 101.70 (Dev8) (Supplemental Table S5). Unlike the other groups, which demonstrated sustained increase in expression during the ripening process, the expression levels of group IIa and group IId attained the highest levels at Dev7 and showed a sudden decrease at Dev8 (Supplemental Table S5).

CaWRKYs expressed during pepper fruit maturation are regulated by different types of stresses

The expression of CaWRKY genes in pepper fruit under abiotic stress conditions (high temperature, high salinity, and drought) was analyzed using qPCR. Stress-induced genes were identified (change fold ≤0.5 as down-regulated or change fold ≥1.5 as up-regulated). The results showed that of all CaWRKY genes expressed in fruit, 26 and 27 genes were regulated by high temperature and high salinity, respectively, whereas only 14 responded to drought stress (Supplemental Tables S6 and S7). All of the 22 CaWRKYs expressed in premature fruits (Dev5 and Dev6), with the exception of CaWRKY31 and CaWRKY60, were regulated by at least one of the tested stress treatments. Meanwhile, all the 30 CaWRKYs expressed during the late-maturity period (Dev7 and Dev8), except for CaWRKY31 and CaWRKY60, were regulated by at least one type of stress (Supplemental Tables S6 and S7). As shown in Supplemental Table S6, a much greater number of genes were regulated by high temperature and high salinity than by drought, and most of them were up-regulated. However, when exposed to drought, most CaWRKYs seem to be down-regulated (Supplemental Table S6). The high consistency of the regulatory pattern of CaWRKY genes under heat and high salinity indicated a close relationship between the two pathways and the function of CaWRKYs in the signaling pathway.

The stress-regulated CaWRKY genes demonstrated diverse expression patterns at different maturing stages of pepper fruit. Some stress-induced CaWRKYs were constitutively expressed throughout the ripening period, whereas others exhibited different expression patterns during pre-maturation and full maturation stages (Supplemental Table S4). In the late maturity stage, not only were more CaWRKYs detected in fruit, but also the expression levels of the corresponding genes increased (Supplemental Table S4), which means that heat-, drought-, and salinity-regulated CaWRKY genes preferentially participated in the process at the late maturity stage. The involvement of many heat-, high salinity-, and drought-regulated CaWRKYs during fruit maturation indicates an important role of these genes in the response of fruit to abiotic stresses.

CaWRKY expression under hormone treatment

Many CaWRKYs have been reported to take part in biological processes regulated by plant hormones7,12. In our study, the qPCR analysis showed that most CaWRKYs expressed in fruit could be regulated by the four hormones tested, namely SA, JA, ABA, and BR (Supplemental Tables S7 and S8). Of all these CaWRKY genes, the expression of 24, 25, 24 and 18 genes was significantly changed (induced or repressed) under SA, JA, ABA and BR treatment, respectively (Supplemental Table S8). The number of up-regulated CaWRKYs was significantly higher than that of down-regulated genes under SA, ABA, and BR treatments, whereas the number of JA-induced and repressed genes remained almost the same (Supplemental Tables S7 and S8). Furthermore, compared to the other plant hormones, CaWRKYs expressed in fruits seemed to be less sensitive to BR. Overall, the expression of CaWRKY genes in different stages of fruit maturity demonstrated divergent response profiles under each of the four hormone applications.

The role of ABA in various biological processes, including fruit ripening, seed dormancy and environmental stress responses, has been widely reported28,36,37. However, to better understand the roles of CaWRKYs in the ABA-dependent fruit ripening and stress responses, we further analyzed the CaWRKY expression profiles under ABA treatment. The results showed that most of the 31 CaWRKYs expressed in fruit were significantly regulated by ABA; 17 were up-regulated and 6 were down-regulated (Supplemental Table S8).

As ABA takes part in various stress responses including those to high salinity, drought, and extreme temperatures37, the expression patterns of all the CaWRKYs expressed in fruits under ABA were compared under the three abiotic stress (high salinity, drought, and heat) treatments. Almost all ABA-induced CaWRKY genes were regulated by at least one of the stresses applied (Supplemental Table S9). These ABA- and stress-regulated CaWRKY genes demonstrated a similar trend, especially under ABA, high-salinity, and heat treatments. Most of them were induced, suggesting a common and positive or sometimes redundant role in the ABA and environmental stress signaling pathways.

Discussion

The WRKY transcription factors, a large protein superfamily, is found abundantly in plants, with hundreds of WRKYs identified up to now24,25,38. The number of WRKY genes in plants range from one in green algae to 75 WRKYs in Arabidopsis3,39. Furthermore, most of these proteins are reported to be involved in defense and resistance processes40,41,42. Recently, the genome of the tomato plant, a representative of the Solanaceae, has been found to encode at least 81 SlWRKYs38. In our study, 61 CaWRKYs were identified using bioinformatics in pepper. It is well known that tomato and pepper, which represent a typical climacteric and non-climacteric fruit, respectively, have emerged as models for fruit ripening. Our study showed that about 36% of CaWRKYs and 35% of SlWRKYs were expressed in pepper and tomato fruits, respectively (Fig. 2), indicating the potentially critical role of WRKYs in plant growth and development, especially in the regulation of fruit ripening in the two species.

In the present study, 16 CaWRKYs were constitutively highly expressed in almost every tissue tested, suggesting their importance and fundamental functions in pepper plant development (Table 3; Fig. 2). At least 25 SlWRKYs were also found to be constitutively highly expressed in most tomato tissues. The subfamily constitution of these CaWRKYs and SlWRKYs were found to be very similar (Table 3). Moreover, 13 pairs of orthologous WRKY were identified (Fig. 5), further indicating the potentially conserved role of these WRKYs in plant development in Solanaceae plants.

Additionally, the work on SlWRKY genes by Huang et al.38 and qPCR results of pepper CaWRKY under biotic and abiotic stress conditions (Supplemental Table S7) indicate that the expression of several pairs of constitutively expressed orthologous WRKYs is highly consistent. For example, CaWRKY36 and SlWRKY53 are both significantly induced by high salinity and B. cinerea infection, CaWRKY11 and SlWRKY74 are up-regulated under drought condition. The highly similar stress response pattern of these orthologous CaWRKY and SlWRKY strongly suggests that the potential roles of WRKY transcription factors in plants are conserved and already formed before the differentiation of tomato and pepper as separate species in the family of Solanaceae.

Fruit ripening is a complex biological process and comprises a series of morphological, physiological, and biochemical processes that encompass pigmentation, nutrition, and metabolism of other flavor substances31,43,44. Numerous transcription factors have been reported to take part in the regulation of fruit ripening. For instance, a MADS-box transcription factor gene (LeMADS-RIN) defined as a master regulator of ripening, was found to affect all known ripening pathways29,45. In addition, transcription factors, such as bHLH, NAC, bZIP, and WRKY, also function during tomato or pepper fruit ripening31,46. In pepper, more than half of the CaWRKY genes were expressed at different stages of ripening. Among them, six highly expressed CaWRKYs that belonged to either group I (4) or group IId (2) were detected at the early maturation stages (Dev5 and Dev6). In the late stages of pepper maturation (Dev7 and Dev8), not only was the average expression level higher compared to that in the pre-maturity stage (Supplemental Table S5), but also the CaWRKY constitution of groups was more diverse. The diverse constitution of CaWRKYs at this stage reflected the more complicated biological processes at work in this stage of fruit ripening. The significant transcript level changes of numerous CaWRKY genes in our study led us to believe that, similar to other maturation-regulating transcription factors identified in tomato (SlNAC1, RIN, and ERF)44,47,48, CaWRKY also plays an important role in the fruit ripening regulatory network.

Early evolutionary origin of the group I WRKYs is supported by the fact that all WRKYs identified in lower plants belong to this group49,50. We found that group I comprised nearly 25% of the total identified CaWRKYs. Of these, only two CaWRKY members have been functionally identified in disease resistance process (CaWRKY13/Ca02g003339 and CaWRKY45/Ca09g001251)51,52. Although current studies attribute group I CaWRKYs to disease resistance, our results suggest that group I CaWRKYs play a more important and fundamental role than other groups in reproductive development, especially in ripening of pepper fruit. Group I proteins composed around 24% of all expressed CaWRKYs in the five tissues analyzed (root, stem, leaf, bud, flower, and fruit). Interesting, nearly 30% of the expressed CaWRKYs during fruit ripening and two of the four CaWRKYs (CaWRKY24 and CaWRKY51) preferentially expressed in fruits belonged to group I. Moreover, the average expression level of group I CaWRKY genes was also higher in pepper fruit tissues, and transcription abundance increased along with the ripening process (Supplemental Table S5). In contrast, the remaining group III CaWRKYs were absent during maturation, revealed by their very low expression level in ripening fruits (Table 2; Supplemental Table S5). These results suggest the possible major role of group I CaWRKYs in pepper fruit development, especially in the fruit maturation process.

As a complex and genetically programmed process characterized by changes in the color, texture, flavor, and aroma30, fruit maturation is affected by various internal and environmental factors, including different hormones like ethylene (ET), auxin (IAA), and ABA28,31,44 and stress conditions such as salinity, high temperature, or cold27,48. For example, IAA is known to retard tomato ripening by regulating ET and ABA28. The down-regulation of auxin-responsive transcription factor gene (ARF) during pepper maturation also indicates the negative role of auxin31. Moreover, salinity positively affects the contents of antioxidant compounds at different ripening stages of pepper fruits27.

In our study, most CaWRKYs expressed in the fruit are regulated by high salinity, drought, or heat and exhibit a similar trend, especially when induced by both high salinity and heat acting together (Supplemental Tables S6 and S7). This phenomenon supported the argument that some abiotic stresses share common gene regulating responses and signal transduction pathways53. Among the three abiotic stresses applied, the effect of both high salinity and heat was more significant as compared to drought on CaWRKY genes expressed in fruits, indicating that the fruit ripening process might be more sensitive to salinity and high temperature.

As a stress responsive plant hormone, ABA can effectively increase the pigmentation and accelerate ripening of sweet cherry fruits54. We found that some CaWRKYs simultaneously regulated by abiotic stresses and ABA followed the same pattern, suggesting that these CaWRKY genes were regulated by stress-induced ABA in fruit. However, some other CaWRKYs demonstrated a different stress-regulated pattern as compared to ABA application. For example, ABA-induced CaWRKY12 and CaWRKY37 were both repressed under high temperature, and the expression of drought-repressed CaWRKY06 increased after ABA treatment (Supplemental Table S7). Comprehensive analysis of CaWRKY expression pattern under ABA treatment revealed that ABA is not only involved in many stress responses, but also reminds us of the complexity of the pepper fruit ripening process, which involves a myriad of CaWRKY transcription factors, interconnected with plant hormones and stress responding pathways.

Materials and Methods

Identification of CaWRKY encoding genes

The amino acid sequences of Capsicum annuum L. ‘Zunla-1’ were downloaded from the pepper genome database (PGD, http://peppersequence.genomics.cn)33 and used to construct a local database using the software Bioedit 7.0 (www.softpedia.com/get/Science-CAD/BioEdit.shtml). A Blastp search was performed using the amino acid sequences of the WRKY transcription factors from tomato and potato38,55. Additionally, the hidden Markov model (HMM) profile of the WRKY domain (Pfam: PF03106) from Pfam 27.0 database (http://pfam.xfam.org/) was used to identify candidate WRKY sequences. The e-value used was 1e−5. After excluding the redundant sequences, the remaining sequences were determined by Pfam 27.0.

Expression analysis of pepper and tomato WRKYs in various tissues

Two Illumina RNA-seq datasets downloaded from the PGD and Tomato Functional Genome Database (TFGD, http://ted.bti.cornell.edu/) were used to analyze the expression patterns of WRKY genes in the root, stem, leaf, bud, flower, and fruit tissues of pepper and in the root, leaf, bud, flower, and fruit tissues of tomato, respectively. Fragments per kilobase of exon model per million mapped (FPKM) values were log2-transformed and heat maps with hierarchical clustering were exhibited using the software Mev 4.9.056.

Phylogenetic analysis of WRKYs

Amino acid sequences of all WRKYs from pepper and tomato were detected using SMART (http://smart.emblheidelberg.de/). Conserved WRKY domains from WRKY transcription factors in pepper and tomato were aligned using ClustalX version 1.83 with default settings (http://www.clustal.org/). A phylogenetic tree was constructed using the software MEGA 5.0557 based on conserved WRKY domains. In the phylogenetic tree, relative branch support was assessed using bootstraps (1000 replicates). Branch lengths were calculated by pairwise comparison of the genetic distances, and missing data were treated by pairwise deletions of gaps.

Plant materials and stress and hormone treatments

Seeds of the pepper cultivar Zhejiao-3 were germinated in plastic pots with a 3:1 (v/v) mixture of peat and vermiculite and grown in a growth room (25 °C/22 °C, 12 h light/12 h dark). The roots, stems, leaves, buds, and flowers were harvested from 8-week-old pepper plants. The 4-week-old seedlings were sprayed with 10 mM salicylic acid (SA), 100 μM jasmonic acid (JA), 50 μM abscisic acid (ABA), and 10 μM brassinolide (BR) solutions, and leaves were collected 12 h later. For abiotic stress treatments, 4-week-old seedlings were exposed to high salt by culturing them in 150 mM NaCl solution for 12 h, exposed to drought by withholding water for 9 d, or to heat by elevating the temperature to 42 °C for 3 h, and leaves were collected at the end of each treatment. All materials were frozen in liquid nitrogen and used for the following expression analyses.

RNA isolation, cDNA synthesis, and quantitative RT-PCR analysis

Total RNA from all samples was isolated using TRIZOL reagent and single-stranded cDNA was synthesized following the manufacturer’s procedure (TIANGEN, Beijing, China). Gene-specific primer pairs were designed using GeneScript real-time PCR primer design (www.genescript.com; Supplemental Table S10) and further verified for their specificity by observing a single amplicon during electrophoresis. qPCR reactions were carried out using the following program: 10 min at 94 °C, 30 cycles of 45 s at 94 °C, 45 s at 55 °C, and 1 min at 72 °C, followed by an extension of 7 min at 72 °C. The ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme genes (UBI1-F:AAGGAAATGTGTGTCTCAAC; UBI1-R: TCCAAATGCCAAACTTCTAG) were used as a reference. Relative gene expression was calculated in accordance with the methods described by Livak and Schmittgen58.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Cheng, Y. et al. Putative WRKYs associated with regulation of fruit ripening revealed by detailed expression analysis of the WRKY gene family in pepper. Sci. Rep. 6, 39000; doi: 10.1038/srep39000 (2016).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (LQ15C150002), National Natural Science Foundation of China (31501749, 31301774, 31272156), Young Talent Cultivation Project of Zhejiang Academy of Agricultural Sciences (2015R23R08E07, 2015R23R08E09), State Key Laboratory Breeding Base for Zhejiang Sustainable Pest and Disease Control (No. 2010DS700124-KF1517), Public Agricultural Technology Research in Zhejiang (2016C32101, 2015C32049), and Technological System of Ordinary Vegetable Industry (CARS-25-G-16).

Footnotes

Author Contributions Y.C. and H.J.W. performed and analyzed most of the experiments in this study, with assistance from J.H.Y., K.F., M.Y.R., Q.J.Y., R.Q.W., Z.M.L. and W.P.D. for critical intellectual input in the design of this study and preparation of the manuscript, and with assistance from G.Z.Z., Z.P.Y. and Y.J.Y. for financial support. H.J.W. and Y.C. designed this study and wrote the manuscript. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

References

- Chen W. et al. Expression profile matrix of Arabidopsis transcription factor genes suggests their putative functions in response to environmental stresses. Plant Cell 14, 559–574 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh K. B., Foley R. C. & Oñate-Sánchez L. Transcription factors in plant defense and stress responses. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 5, 430–436 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rushton P. J. et al. WRKY transcription factors. Trends Plant Sci. 15, 247–258 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamasaki K. et al. Solution structure of an Arabidopsis WRKY DNA binding domain. Plant Cell 17, 944–956 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishiguro S. & Nakamura K. Characterization of a cDNA-encoding a novel DNA-binding protein, Spf1, that recognizes Sp8 sequences in the 5′ upstream regions of genes-coding for sporamin and β-amylase from sweet-potato. Mol. Gen. Genet. 244, 563–571 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rushton P. J. et al. Interaction of elicitor-induced DNA-binding proteins with elicitor response elements in the promoters of parsley PR1 genes. EMBO J. 15, 5690–5700 (1996). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H. et al. Roles of Arabidopsis WRKY18, WRKY40 and WRKY60 transcription factors in plant responses to abscisic acid and abiotic stress. BMC Plant Biol. 10, 1 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B. et al. Tomato WRKY transcriptional factor SlDRW1 is required for disease resistance against Botrytis cinerea and tolerance to oxidative stress. Plant Sci. 227, 145–156 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai H. Y. et al. CaWRKY6 transcriptionally activates CaWRKY40, regulates Ralstonia solanacearum resistance, and confers high-temperature and high-humidity tolerance in pepper. J. Exp. Bot. 66, 3163–3174 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dang F. F. et al. Overexpression of CaWRKY27, a subgroup lle WRKY transcription factor of Capsicum annuum, positively regulates tobacco resistance to Ralstonia solanacearum infection. Physiol. Plant. 150, 397–411(2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X. C. et al. Over-expression of SlWRKY39 leads to enhanced resistance to multiple stress factors in tomato. J. Plant Biol. 58, 52–60 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Shang Y. et al. The Mg-chelatase H subunit of Arabidopsis antagonizes a group of WRKY transcription repressors to relieve ABA-responsive genes of inhibition. Plant Cell 22, 1909–1935 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H. et al. Mutation of WRKY transcription factors initiates pith secondary wall formation and increases stem biomass in dicotyledonous plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 107, 22338–22343 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suttipanta N. et al. The transcription factor CrWRKY1 positively regulates the terpenoid indole alkaloid biosynthesis in Catharanthus roseus. Plant Physiol. 157, 2081–2093 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson C. S., Kolevski B. & Smyth D. R. TRANSPARENT TESTA GLA-BRA2, a trichome and seed coat development gene of Arabidopsis, encodes a WRKY transcription factor. Plant Cell 14, 1359–1375 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo M. et al. MINISEED3 (MINI3), a WRKY family gene, and HAIKU2 (IKU2), a leucine-rich repeat (LRR) KINASE gene, are regulators of seed size in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 102, 17531–17536 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang W. & Yu D. Arabidopsis WRKY2 transcription factor mediates seed germination and postgermination arrest of development by abscisic acid. BMC Plant Biol. 9, 96 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robatzek S. & Somssich I. E. Targets of AtWRKY6 regulation during plant senescence and pathogen defense. Genes Dev. 16, 1139–1149 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao Y. et al. Targets of the WRKY53 transcription factor and its role during leaf senescence in Arabidopsis. Plant Mol. Biol. 55, 853–867 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y. et al. Structural and functional analysis of VQ motif-containing proteins in Arabidopsis as interacting proteins of WRKY transcription factors. Plant Physiol. 159, 810–825 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreasson E. et al. The MAP kinase substrate MKS1 is a regulator of plant defense responses. EMBO J. 24, 2579–2589 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu J. L. et al. Arabidopsis MAP kinase 4 regulates gene expression through transcription factor release in the nucleus. EMBO J. 27, 2214–2221 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang A. et al. The VQ motif protein IKU1 regulates endosperm growth and seed size in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 63, 670–679 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong J., Chen C. & Chen Z. Expression profiles of the Arabidopsis WRKY gene superfamily during plant defense response. Plant Mol. Biol. 51, 21–37 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross C. A., Liu Y. & Shen Q. X. J. The WRKY gene family in rice (Oryza sativa), J. Integr. Plant Biol. 49, 827–842 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Klee H. J. & Giovannoni J. J. Genetics and control of tomato fruit ripening and quality attributes. Annu. Rev. Genet. 45, 41–59 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro J. et al. Changes in the contents of antioxidant compounds in pepper fruits at different ripening stages, as affected by salinity. Food Chem. 96, 66–73 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- Su L. et al. Carotenoid accumulation during tomato fruit ripening is modulated by the auxin-ethylene balance. BMC Plant Biol. 15, 1 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vrebalov J. et al. A MADS-box gene necessary for fruit ripening at the tomato ripening-inhibitor (rin) locus. Science 296, 343–346 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giovannoni J. Genetic regulation of fruit development and ripening. Plant Cell 16, S170–S180 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S. et al. Non-climacteric fruit ripening in pepper: increased transcription of EIL-like genes normally regulated by ethylene. Funct. Integr. Genomics 10, 135–146 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huh S. U. et al. Capsicum annuum WRKY transcription factor d (CaWRKYd) regulates hypersensitive response and defense response upon Tobacco mosaic virus infection. Plant Sci. 197, 50–58 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin C. et al. Whole-genome sequencing of cultivated and wild peppers provides insights into Capsicum domestication and specialization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 111, 5135–5140 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S. et al. Genome sequence of the hot pepper provides insights into the evolution of pungency in Capsicum species, Nat. Genet. 46, 270–278 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diao W. P. et al. Genome-Wide Identification and Expression Analysis of WRKY Gene Family in Capsicum annuum L. Front. Plant Sci. 7, 211 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Toh S. et al. High temperature-induced abscisic acid biosynthesis and its role in the inhibition of gibberellin action in Arabidopsis seeds. Plant Physiol. 146, 1368–1385 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasilewska A. et al. An update on abscisic acid signaling in plants and more. Mol. Plant 1, 198–217 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang S. X. et al. Genome-wide analysis of WRKY transcription factors in Solanum lycopersicum. Mol. Genet. Genomics 287, 495–513 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangelsen E. et al. Phylogenetic and comparative gene expression analysis of barley (Hordeum vulgare) WRKY transcription factor family reveals putatively retained functions between monocots and dicots. BMC Genomics 9, 1 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J. S. et al. Defense-related transcription factors WRKY70 and WRKY54 modulate osmotic stress tolerance by regulating stomatal aperture in Arabidopsis. New Phytol. 200, 457–472 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tripathi P., Rabara R. C. & Rushton P. J. A systems biology perspective on the role of WRKY transcription factors in drought responses in plants. Planta 239, 255–266 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding Z. J. et al. Transcription factor WRKY46 regulates osmotic stress responses and stomatal movement independently in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 79, 13–27 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa F. et al. Use of homologous andheterologous gene expression profiling tools to characterize transcriptiondynamics during apple fruit maturation and ripening. BMC Plant Biol. 10, 1 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma N. et al. Overexpression of tomato SlNAC1 transcription factor alters fruit pigmentation and softening. BMC Plant Biol. 14, 1 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martel C. et al. The tomato MADS-boxtranscription factor RIPENING INHIBITOR interacts with promotersinvolved in numerous ripening processes in a COLORLESS NONRIPENING dependent manner. Plant Physiol. 157, 1568–1579 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujisawa M. et al. A large-scale identification of direct targets of the tomato MADS box transcription factor RIPENING INHIBITOR reveals the regulation of fruit ripening. Plant Cell 25, 371–386 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung M. Y. et al. A tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) APETALA2/ERF gene, SlAP2a, is a negative regulator of fruit ripening. Plant J. 64, 936–947 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin G. et al. Unraveling the regulatory network of the MADS box transcription factor RIN in fruit ripening. Plant J. 70, 243–255 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu K. L. et al. The WRKY family of transcription factors in rice and Arabidopsis and their origins. DNA Res. 12, 9–26 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y. J. & Wang L. J. The WRKY transcription factor superfamily: its origin in eukaryotes and expansion in plants. BMC Evol. Biol. 5, 1–12 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park C. J. et al. A hot pepper gene encoding WRKY transcription factor is induced during hypersensitive response to Tobacco mosaic virus and Xanthomonas campestris. Planta 223, 168–179 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y. et al. CaWRKY58, encoding a group I WRKY transcription factor of Capsicum annuum, negatively regulates resistance to Ralstonia solanacearum infection. Mol. Plant Pathol. 14, 131–144 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma S. & Bohnert H. J. Integration of Arabidopsis thaliana stress-related transcript profiles, promoter structures, and cell specific expression. Genome Biol. 8, R49 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren J. et al. Role of abscisic acid and ethylene in sweet cherry fruit maturation: molecular aspects. N. Z. J. Crop Hortic. Sci. 39, 1–14 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Huang S. X. & Liu Y. S. The bioinformatics analysis of WRKY transcription factors in potato, Chinese Journal of Appling Environmental Biology, 19, 205–214 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Saeed A. I. et al. TM4: a free, open-source system for microarray data management and analysis. Biotechniques 34, 374–378 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K. et al. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol. Biol. Evol. 28, 2731–2739 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak K. J. & Schmittgen T. D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-delta delta C(T))method. Methods 25, 402–408 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.