Abstract

Purpose

Temporary and reversible downregulation of metabolism may improve the survival of tissues exposed to non-physiological conditions during transport, in vitro culture, and cryopreservation. The objectives of the study were to (1) optimize the concentration and duration of carbonyl cyanide 4-(trifluoromethoxy)phenylhydrazone (FCCP—a mitochondrial uncoupling agent) exposures for biopsies of domestic cat ovarian tissue and (2) examine the effects of FCCP pre-exposures on follicle integrity after tissue culture and/or cryopreservation.

Methods

Biopsies of cat ovarian tissue were first treated with various concentrations of FCCP (0, 10, 40, or 200 nM) for 10 or 120 min to determine the most suitable pre-exposure conditions. Based on these results, tissues were pre-exposed to 200 nM FCCP for 120 min for the subsequent studies on culture and cryopreservation. In all experiments and for each treatment group, tissue activity and integrity were measured by mitochondrial membrane potential (relative optical density of rhodamine 123 fluorescence), follicular viability (calcein assay), follicular morphology (histology), granulosa cell proliferation (Ki-67 immunostaining), and follicular density.

Results

Ovarian tissues incubated with 200 nM FCCP for 120 min led to the lowest mitochondrial activity (1.17 ± 0.09; P < 0.05) compared to control group (0 nM; 1.30 ± 0.12) while maintaining a constant percentage of viable follicles (75.3 ± 7.8 %) similar to the control group (71.8 ± 11.7 %; P > 0.05). After 2 days of in vitro culture, percentage of viable follicles (78.8 ± 8.9 %) in similar pre-exposure conditions was higher (P < 0.05) than in the absence of FCCP (61.2 ± 12.0 %) with percentages of morphologically normal follicles (57.6 ± 17.3 %) not different from the fresh tissue (70.2 ± 7.1 %; P > 0.05). Interestingly, percentages of cellular proliferation and follicular density were unaltered by the FCCP exposures. Based on the indicators mentioned above, the FCCP-treated tissue fragments did not have a better follicle integrity after freezing and thawing.

Conclusions

Pre-exposure to 200 nM FCCP during 120 min protects and enhances the follicle integrity in cat ovarian tissue during short-term in vitro culture. However, FCCP does not appear to exert a beneficial or detrimental effect during ovarian tissue cryopreservation.

Keywords: Carbonyl cyanide 4-(trifluoromethoxy)phenylhydrazone (FCCP), Domestic cat, Ovarian tissue, In vitro culture, Mitochondrial membrane potential, Follicular viability

Introduction

Ovarian tissue cryopreservation is a critical approach to ensure the fertility preservation in animal models as well as in human patients undergoing chemotherapy or radiotherapy for cancer treatment [1, 2]. These options also are particularly interesting in endangered species conservation to bank ovarian tissue containing an abundant amount of preantral and primordial follicles for individuals undergoing surgical ovarian removal or dying unexpectedly [2–4]. In this type of studies, the domestic cat represents an excellent biomedical model for non-domestic cats and human [3, 5, 6]. In association with the freezing techniques, culture of the ovarian tissue in vitro is a fundamental approach to reanimate the tissue and grow more oocytes to an advanced stage [5, 7, 8]. However, there may be several hours between the ovarian tissue collection and the cryopreservation process itself which compromises (through ischemia and oxidative stress) the viability and developmental competence of the germ cells within the gonads [3, 9, 10]. During this critical period, cellular respiration in mitochondria is still occurring despite the ischemic environment [10–12]. Thus, reversibly reducing the metabolic activity of the cells (by using a metabolic disrupting agent) is an interesting option for protecting and prolonging the tissue integrity. In addition, some studies have demonstrated that the cell survival can be increased during and after cryopreservation in mouse, rat, and human cells by using metabolic quiescence agent [13–15]. Mitochondrion is a key organelle of the cell essential for the survival and proliferation of cells due to the role in electron transport chain in aerobic cellular respiration. Carbonyl cyanide 4-(trifluoromethoxy)phenylhydrazone (FCCP), is a commonly used proton ionophore as a mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation inhibitor. It is an uncoupling agent disturbing the process of ATP synthesis by transporting hydrogen ions through a mitochondrial membrane [14]. For instance, incubation with low dosage of FCCP to modify the mitochondrial membrane potential prior to a stress has already been shown to be beneficial on human neuronal cell viability [15]. However, no reports on that strategy are available on the domestic cat ovarian tissue. Our recent cryopreservation studies on that type of biomaterials used classical indicators of tissue integrity and demonstrated that, despite encouraging results, a lot remained to be understood and improved [16]. The objective of the present study therefore was to investigate the effects of FCCP pre-exposure on follicle integrity after tissue culture and on follicle integrity after short-term culture followed by cryopreservation.

Materials and methods

Chemicals

All chemicals and reagents were purchased from Sigma Chemical Company (St. Louis, MO, USA), unless otherwise stated.

Collection of ovarian tissue

Ovaries were obtained from domestic cats (8 weeks to 2 years old) after routine ovariohysterectomy at local veterinary clinics and transported in phosphate-buffered solution at 4 °C to the laboratory within 12 h of excision. Ovarian cortical fragments were removed from the outermost part of the ovaries by using surgical blades and curved scissors [16]. Large antral follicles (diameter > 1 mm) and luteal tissue areas were excluded. Cortical tissues were cut into small fragments in the area of 1 × 1 mm2 and approximately 200 μm thickness in a holding medium consisting of Eagle’s MEM supplemented with 2 mM L-glutamine, 10 μg/mL insulin, 5.5 μg/mL transferrin, 5.0 μg/mL sodium selenite, 0.3 % (w/v) bovine serum albumin (BSA), 10 mM HEPES, 100 μg/mL penicillin G sodium, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin sulfate.

Ovarian tissue culture

Ovarian tissue culture was performed as previously reported [17]. Briefly, ovarian cortical fragments were transferred into 4-well cell culture plates (Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark) containing a cube hexahedron of 1.5 % agarose gel (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) sized approximately 7 × 7 × 7 mm3 soaked in a culture medium incubated at 38.5 °C in 5 % CO2 in humidified air. The culture medium was Eagle’s MEM supplemented with 5.5 μg/mL insulin, 5.5 μg/mL transferrin, 6.7 ng/mL selenium, 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 μg/mL penicillin G sodium, 100 μg/mL streptomycin sulfate, 0.05 mM ascorbic acid, 10 ng/mL porcine FSH (Folltropin-V, Bioniche Animal Health, Belleville, Canada), and 0.1 % (w/v) polyvinyl alcohol. Half of the volume of culture media was changed every 48 h until the day of examination.

Cryopreservation of the ovarian tissue with slow freezing method and thawing

Cryopreservation was performed according to previous reports [10, 16, 18]. Ovarian cortical fragments were transferred from holding medium to cryopreservation medium contained with L-15 medium supplemented with 1.5 M DMSO (Fluka Chemie GmbH, Buchs, Spain) and 0.1 M sucrose for 5 min at 4 °C. After exposure to the cryopreservation medium, tissue fragments were transferred into precooled cryovials (1.6-mL cryogenic vial; Corning, NY, USA) and remained at 4 °C for a further 10 min. Then, the cryovials were moved to a passive cooling container (CoolCell; BioCision, Larkspur, CA, USA) to achieve the −1 °C/min cooling rate and placed in an −80 °C freezer. After 24 h, the cryovials were taken out of the freezer and immersed directly in liquid nitrogen.

Thawing was performed by immersing the vials in a 37 °C water bath for 3 min. The thawed fragments were then rapidly placed into a first thawing medium containing L-15 medium with 0.75 M DMSO and 0.25 M sucrose at room temperature for 10 min and transferred to a second thawing medium containing L-15 with 0.25 M sucrose for 10 min.

Follicular viability assessment

The viability of tissue follicles was assessed by using calcein acetoxymethyl ester (CAM; Invitrogen, Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA)/ethidium homodimer-1 (EthD-1; Invitrogen) [18]. The staining was performed by transferring ovarian cortical fragments into a mixture of 2 μM CAM and 5 μM EthD-1 in the holding medium for 15 min in the dark. Stained follicles were examined under a fluorescence microscope (BX41; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) at ×400 magnification. Preantral follicle with the oocyte and granulosa cells stained green by calcein was considered viable follicle, and follicle that has red staining of EthD-1 in the oocyte or granulosa cells was considered non-viable follicle. For each ovarian biopsy, ten random high-power fields were observed and pooled percentage of viable follicles was recorded.

Histological analysis and classification

Ovarian tissue fragments were fixed in 4 % paraformaldehyde and transferred to 70 % ethanol after 24 h. Tissue fragments were dehydrated in a graded series of ethanol solutions and embedded in a paraffin block. Each cortical piece was serially dissected into 4 μM sections and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Tissues were examined and photographed under a microscope (BX41, Olympus) and microscope camera (SPOT RT3, Diagnostic Instruments, Inc., Sterling Heights, MI, USA). Follicles containing oocytes with a visible nucleus were observed and counted.

Classification of follicle morphology was performed according to a previous study [17]. Preantral follicles within the tissue with structural intact oocyte and granulosa cells were classified as normal. Abnormal follicles contained pyknotic, fragmented, or shrunken nucleus in the oocyte and/or the granulosa cells. The percentage of morphologically normal follicles was determined as the number of normal follicles divided by total follicles within the whole sections.

Follicle density was determined by the number of preantral follicles per area of 1 mm2 of ovarian tissue section under the microscope imaging program (SPOT 4.0, Diagnostic Instruments, Inc., Sterling Heights, MI).

Mitochondrial membrane potential assessment

Mitochondrial membrane potential was assessed according to previous studies [19–21]. In brief, the tissue fragments were incubated with holding medium supplemented with 10 μg/mL rhodamine 123 (Invitrogen), a cell-permeable cationic dye that preferentially enters mitochondria based on a highly negative mitochondrial membrane potential. As a result, this phenomenon reflected the mitochondrial activity within the cell. Tissue fragments were stained at 37 °C for 15 min and then washed out with holding medium. Tissues then were examined and photographed under a fluorescence microscope (BX41, Olympus) and microscope camera (SPOT RT3, Diagnostic Instruments Inc.) at ×200 magnification with the exposure of excitation signal of 485 nm and collected the emission signal at 520 nm. Parameters of the microscope camera settings were unchanged throughout the experiments. The intensity of rhodamine 123 staining was determined by using image analysis software (ImageJ; National Institute of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA). Regions of interest for each fragment were drawn according to the area of the tissue fragment to measure the fluorescence intensity. The intensity of the fluorescence signal was expressed as relative optical density (ROD) of tissue rhodamine 123 fluorescence emission and the background of the media with rhodamine 123, calculated by using the formula of ROD = ODspecimen / ODbackground = log (GLblank / GLspecimen) / log (GLblank / GLbackground), where GL is the mean gray level for the stained area (specimen) and background area and blank is the gray level measured after the slide was removed. All GLs were obtained by using dark background mode for fluorescence images. Parameters involved in fluorescence intensity, such as gain signal and pinhole size, were constant for all measurements performed. The tissue with high intensity of rhodamine 123 indicated the high mitochondrial membrane potential in the stained cells [22].

Proliferation assessment

The protocol of granulosa cell proliferation by using Ki-67 immunostaining was adapted from a previous study [23]. After histological tissue preparation, sections were treated for antigen retrieval in an autoclave machine (121 °C, 1.2 kg/cm2) for 30 min in citrate buffer (pH = 6.0). Endogenous peroxidase activity was inhibited by incubating the tissue slides with 3 % (v/v) hydrogen peroxide in methanol for 10 min, then treated with normal horse serum for 30 min at room temperature. Tissue slides were incubated with monoclonal mouse anti-human Ki-67 antigen clone MIB-1 (DAKO, Glostrup, Denmark) in a humidified chamber at room temperature for 180 min. Afterwards, the slides were treated with anti-mouse made in horse secondary antibody at room temperature for 30 min. Detection was performed by using avidin-biotin complex (Vector, Vector Laboratories Inc., Burlingame, CA, USA) by incubating the tissue for 60 min at room temperature, followed by incubation with ImmPACT DAB (Vector) for 2 min at room temperature. Sections then were counterstained with Mayer’s hematoxylin. PBS was used instead of Ki-67 antibody in negative controls. Preantral follicle with positive brown staining of DAB in at least one granulosa cell nucleus was classified as a proliferating follicle.

Experimental design

Short-term effect of FCCP exposure on cat ovarian tissue

For each of the 12 replicates, pooled ovarian tissue fragments were obtained from two ovaries. Six tissue fragments were allocated to each experimental group. Tissue fragments were incubated in the culture medium supplemented with FCCP in the concentrations of 10, 40, and 200 nM in 4-well plates incubated at 38.5 °C in 5 % CO2 in humidified air. All groups were tested for viability and potential membrane after 10 and 120 min of incubation. The groups incubated with culture medium without FCCP were used as controls.

Long-term effect of FCCP pre-exposure after ovarian tissue culture up to 7 days

Two ovaries were pooled in each replicate and processed for ovarian cortex isolation. The experiment was performed for 12 replicates. For each experimental group, ten cortical fragments were pre-exposed with FCCP (concentration and time according to the first experiment) before in vitro cultured. The ovarian tissue fragments were allocated to the experimental groups of various concentrations of FCCP (0, 10, 40, or 200 nM) for 2 or 7 days. When reaching the endpoint, the ovarian fragments were examined for follicular viability, mitochondrial membrane potential, histological analysis, and proliferation marker immunostaining. The groups pre-exposed with culture medium without FCCP were used as controls.

Cryopreservation of domestic cat ovarian tissue after pre-exposure with FCCP

This final experiment was performed for 16 replicates. Twenty ovarian cortical fragments were allocated in each experimental group. The fragments were pre-exposed in the optimal conditions defined in the second experiment. At the end of culture, all tissues were washed out with the holding medium for 15 min before cryopreservation. The tissues were stored in liquid nitrogen. The thawed ovarian fragments were assessed for follicular viability, mitochondrial activity, histological analysis, and proliferation marker. The cryopreservation control group was the group of fresh tissues that have undergone freeze-thawing right after ovarian cortical fragment extraction, and the culture control is the group that was cultured for 2 days without FCCP pre-exposure before cryopreservation.

Statistical analysis

The percentage of follicular viability, the percentage of morphologically normal follicles, the follicular density, the percentage of the positive Ki-67 marker, and the mitochondrial membrane potential data were expressed as mean ± SD. Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was performed to evaluate the normal distribution of each dataset. The normal distribution data were evaluated by using general linear mixed models, and the data that did not pass the normal distribution test were evaluated by Kruskal-Wallis analysis of variance. Dependent variables included the percentage of follicular viability, percentage of morphologically normal follicles, follicle density, percentage of the positive Ki-67 marker, and mitochondrial membrane potential. The effect of treatments (concentrations and incubation durations of FCCP, concentrations and culture durations of FCCP, and FCCP culture duration prior to cryopreservation) was included in the statistical models as fixed effects. The animal identities and tissue number nested within the animal ID were included in the models as random effects. Significant differences were considered when P < 0.05.

Results

Immediate effect of FCCP incubation on mitochondrial membrane potential of the ovarian tissue and on follicle viability

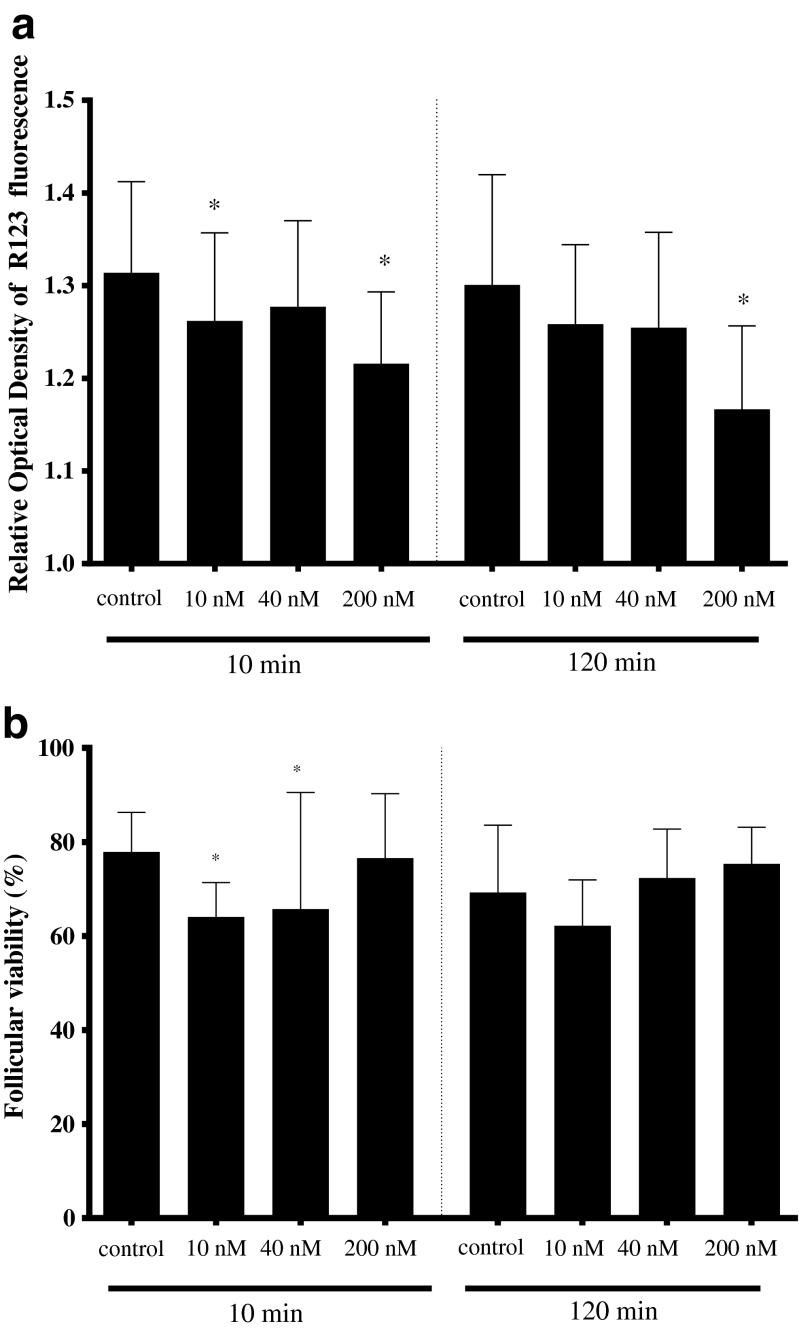

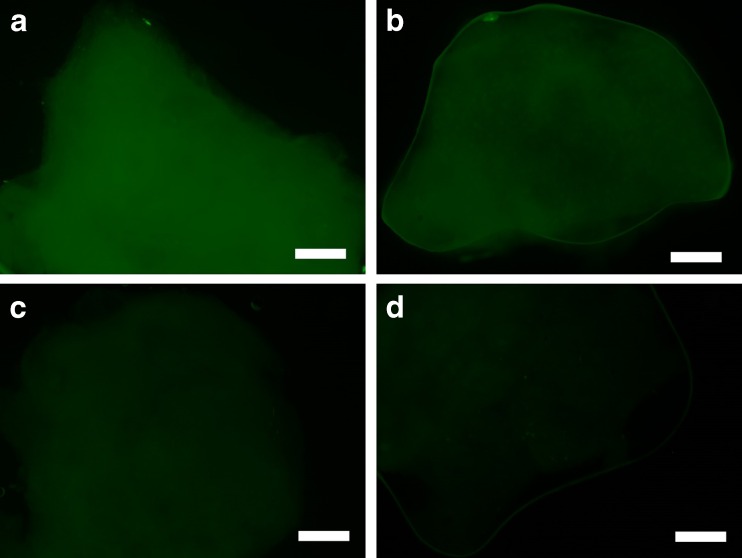

The intensity of rhodamine 123 fluorescence was lower (P < 0.05) after 10-min incubation with 10 and 200 nM (1.26 ± 0.9 and 1.21 ± 0.08, respectively) than the control group (0 nM; 1.34 ± 0.11, Fig. 1a), whereas it was unchanged (P > 0.05) with 40 nM (1.28 ± 0.09; Fig. 1a). The percentage of viable follicle after 10-min incubation with 10 nM FCCP group was lower (64.0 ± 7.3 %; P < 0.05) than the control group (77.9 ± 8.4 %; Fig. 1b). However, the percentage of viable follicle was not different (P > 0.05) after 10-min exposure to 40 and 200 nM (65.7 ± 24.8 and 76.6 ± 13.7, respectively; Fig. 1b). After 120 min of incubation, the intensity of the rhodamine 123 fluorescence was lower with 200 nM (1.17 ± 0.09; P < 0.05) than in the control group (1.30 ± 0.12; Figs. 1a and 2d). Interestingly, percentages of viable follicles were not modified by any of the 120-min exposures (62.2 ± 9.8, 74.1 ± 8.7, 75.3 ± 7.8, and 71.8 ± 11.7 in 10, 40, 200 nM, and control, respectively, Fig. 1b). Based on those results, the 120-min exposure was selected for further explorations.

Fig. 1.

Impact of incubation with 0 (control), 10, 40, or 200 nM FCCP for 10 or 120 min on a the mitochondrial activities (measured by relative optical density of rhodamine 123 fluorescence) in the cat ovarian tissue and b percentage of viable follicles. Asterisks above the bar indicate a significant difference with the control group within the same incubation duration (P < 0.05). Values are expressed as mean ± SD

Fig. 2.

Fluorescence of rhodamine 123 in ovarian tissues after 120-min incubation in a 0 nM (control), b 10 nM, c 40 nM, or d 200 nM FCCP. Bar = 100 μm

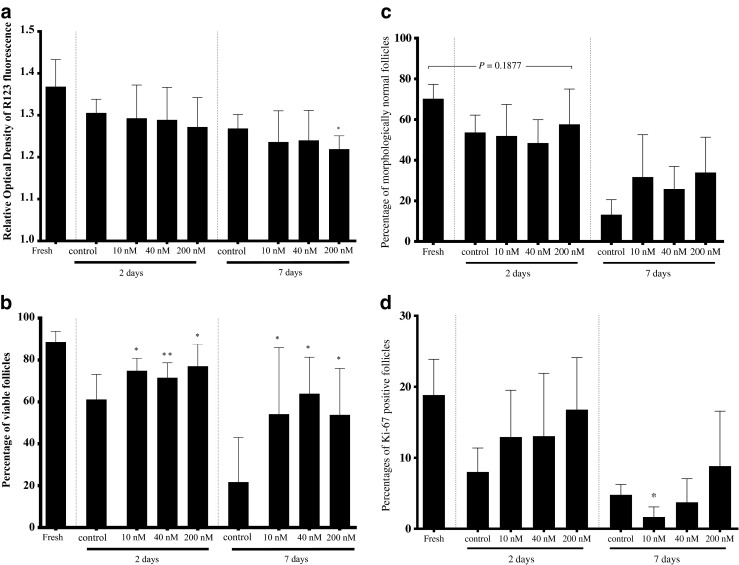

Reversible and beneficial effects of FCCP exposure on subsequent follicle integrity during in vitro culture of ovarian tissue

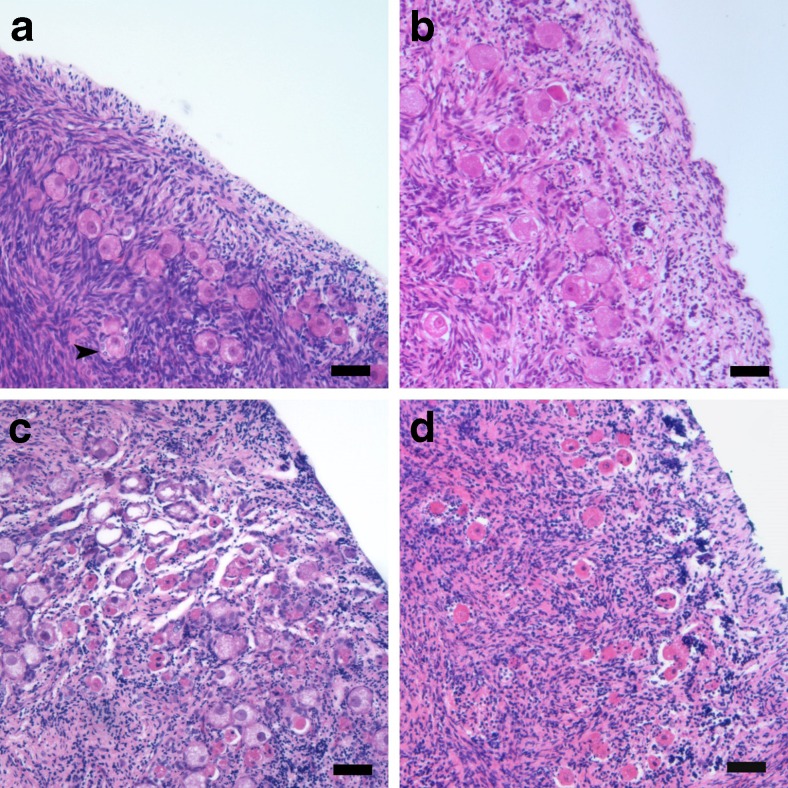

The fresh tissue tended to have a higher rhodamine 123 fluorescence intensity (1.37 ± 0.06) than the other groups (P < 0.1; Fig. 3a). Same observation was made for the percentages of viable follicles in the fresh tissue (Fig. 3b). After 120-min FCCP pre-exposures with various concentrations and 2 days of culture, the intensity of the rhodamine 123 fluorescence remained constant (1.29 ± 0.08, 1.29 ± 0.07, and 1.27 ± 0.07 for 10, 40, and 200 nM, respectively) and not different (P > 0.05) from the control group (0 nM; 1.31 ± 0.01; Fig. 3a). Percentages of viable follicles with 10, 40, and 200 nM FCCP were higher (74.9 ± 6.0, 71.6 ± 7.1, and 78.8 ± 8.9, respectively; P < 0.05; Fig. 3b) than the control group (0 nM; 61.2 ± 12.0). For the percentages of morphologically normal follicles, tissues cultured with 200 nM FCCP were able to maintain morphologically normal follicles for 2 days (57.6 ± 17.3; P > 0.05) even compared with fresh tissues (70.2 ± 7.1; Figs. 3c and 4b). However, the tissues treated with 10 nM FCCP, 40 nM, and the control (0 nM) tended to have lower percentages of normal follicles (53.6 ± 8.5, 51.9 ± 15.5, and 48.4 ± 11.5, respectively) than the fresh group (P < 0.1). Percentages of proliferating follicles in all 2-day FCCP-treated groups (ranging from 13.0 to 16.8 %; P > 0.05) were not different from the fresh tissue (18.8 ± 5.0 %; Fig. 3d). Interestingly, the 2-day control tissues (0 nM) had percentages of proliferating follicles (8.0 ± 3.4 %; P < 0.05) than the fresh group but not lower than other 2-day treatment groups (P > 0.05). Regarding follicular density, tissues exposed to any FCCP concentration for 120 min were not different (ranging from 19.1 to 23.5 follicles per mm2) from the fresh group (27.9 ± 10.0; P > 0.05). When comparing the follicular density in each follicular stage, primordial follicles were the majority of the follicles within the fresh (85.1 ± 14.2 %) and 2-day cultured tissues (ranging from 66.4 to 74.6 %; P > 0.05).

Fig. 3.

Impact of 120-min pre-exposure to 0 (control), 10, 40, or 200 nM FCCP on a mitochondrial activity (relative optical density of rhodamine 123 fluorescence), b percentages of viable follicles, c percentages of morphologically normal follicles, and d percentages of Ki-67-positive follicles in cat ovarian tissues after 2 or 7 days of in vitro culture. Asterisks above bars indicate a significant difference with the control group within the same incubation duration (P < 0.05). Values are expressed as mean ± SD

Fig. 4.

Histological sections of cat ovarian cortex a from fresh tissue, b after 2 days of culture, c after 7 days of culture, and d after pre-exposure to 200 nM of FCCP for 120 min and 7 days of culture. Representative primary follicle is identified with an arrowhead. Bar = 50 μm

After 120-min FCCP pre-exposures and 7 days of culture, the intensities of the rhodamine 123 fluorescence of the tissue with 10 and 40 nM FCCP were not different (1.24 ± 0.07 and 1.25 ± 0.06, respectively; P > 0.05) from the control group (0 nM; 1.27 ± 0.03; Fig. 3a). With 200 nM FCCP, however, tissues had lower rhodamine 123 fluorescence intensity (1.22 ± 0.03; P < 0.05) than the control group (Fig. 3a). Percentages of viable follicles in all FCCP-treated tissues were higher (54.2 ± 31.8, 63.9 ± 17.4, and 53.8 ± 22.1 % with 10, 40, and 200 nM FCCP, respectively; P < 0.05) than the control group (0 nM; 21.7 ± 21.3 %; Fig. 3b). Percentages of morphologically normal follicles were not different after 7 days of culture (Fig. 3c) even if tissues treated with FCCP tended to contain higher percentages (34.7 ± 20.8, 25.8 ± 11.1, and 33.92 ± 17.3 in 10, 40, and 200 nM FCCP groups, respectively; P < 0.1) than the control group (0 nM; 13.2 ± 7.4, Figs. 3c and 4c, d).

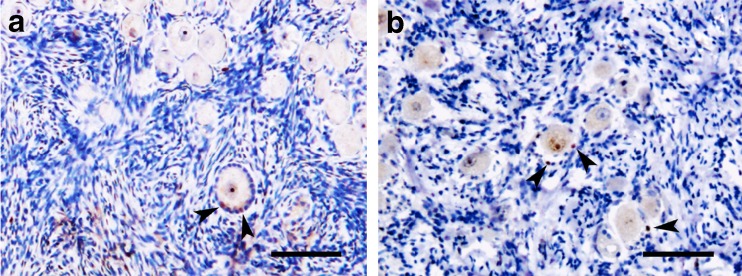

All tissues had the same level of follicular proliferation except the group of 10 nM FCCP that had a lower percentage of proliferation follicles (1.7 ± 1.4 %; P < 0.05) than the control group (0 nM; 4.8 ± 1.5 %; Fig. 3d). Notably, tissues exposed to 200 nM FCCP were the only group in this culture condition that had the same level of proliferation (8.8 ± 7.7 %) as the fresh group (P > 0.05; Figs. 3d and 5a, b). The only tissue that had the same level of follicular density as the fresh group was the group of 200 nM (14.8 ± 10.1 follicles per mm2; P > 0.05). Percentages of primordial follicle were lower (ranging from 33.9 to 44.3 %; P < 0.05) than the percentages of primary follicle (ranging from 53.0 to 57.1 %) regardless of the FCCP concentration.

Fig. 5.

Immunostaining of proliferation marker (Ki-67) in cat ovarian cortex a from fresh tissue and b after pre-exposure to 200 nM of FCCP for 120 min and 7 days of culture. Brown staining in the granulosa cells of the growing follicle is identified by arrowheads. Bar = 100 μm

Effect of incubation with 200 nM FCCP on the survival of ovarian tissue during cryopreservation

According to the previous experiments, pre-exposure to 200 nM FCCP for 120 min and 2 days of culture were the most suitable conditions for the maintenance of tissue and follicle integrity. Cryopreservation of ovarian tissue without pre-exposure to FCCP decreased the intensity of rhodamine 123 fluorescence (P < 0.05; Table 1). FCCP pre-exposure and culture for 2 days did not improve the overall mitochondrial activity of the ovarian tissue after cryopreservation (P > 0.05; Table 1). The percentage of viable follicles within the tissues pre-exposed with 200 nM FCCP and cultured for 2 days before cryopreservation was lower (P < 0.05) than the group without FCCP and cryopreserved control (Table 1) but remained at the relatively high level (>60 %). Percentages of proliferating follicles were decreased in all treatment groups compared to the fresh control (P < 0.05), but no detrimental effect of FCCP exposure was noted (Table 1). Similarly, percentages of morphologically normal follicles were lower than the fresh and cryopreserved tissues (P < 0.05) regardless of the FCCP exposure (Table 1). Preantral follicular density was unaltered in FCCP-treated group (P > 0.05) when compared to cryopreserved controls, 2-day culture control, or fresh tissues (Table 1). Primary follicle density from ovarian tissues that were pre-exposed to 200 nM FCCP was not different (P > 0.05) from the cryopreserved control and 2-day culture control groups but was lower (P < 0.05) than in the fresh group (Table 1).

Table 1.

Mitochondrial activity (relative optical density of rhodamine 123 staining), follicular viability, cellular proliferation, follicle morphology, and follicular density in cat ovarian tissues (fresh, cryopreserved, or pre-exposed to 200 nM FCCP for 120 min followed by 2 days of culture and cryopreservation)

| Fresh | Cryopreserved control | Cryopreserved after FCCP pre-exposure and 2 days of culture | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 nM | 200 nM | |||

| Mitochondrial activity (relative optical density) | 1.32 ± 0.03a | 1.22 ± 0.04b | 1.26 ± 0.04b | 1.23 ± 0.07b |

| Viable follicles (%) | 81.8 ± 7.5a | 73.9 ± 10.2b | 69.3 ± 12.5b | 60.6 ± 12.5c |

| Proliferating follicles (%) | 25.0 ± 9.2a | 7.9 ± 5.9b | 11.0 ± 5.4b | 6.4 ± 3.1b |

| Morphologically normal follicle (%) | 78.8 ± 9.6a | 63.8 ± 12.4a | 44.8 ± 10.9b | 42.4 ± 10.5b |

| Preantral follicle density (follicle number/mm2) | 44.2 ± 18.1 | 23.1 ± 13.1 | 27.2 ± 15.8 | 26.4 ± 11.8 |

| Primordial follicle | 32.6 ± 20.2 | 20.4 ± 17.3 | 23.7 ± 21.2 | 21.7 ± 13.0 |

| Primary follicle | 10.8 ± 8.9a | 1.6 ± 1.1b | 2.1 ± 2.4b | 3.6 ± 1.0b |

| Secondary follicle | 0.7 ± 0.7 | 1.2 ± 2.3 | 1.4 ± 1.6 | 1.2 ± 1.8 |

Within the same row, data with the different superscripts (a,b,c) are significantly different (P < 0.05). Values are expressed as mean ± SD

Discussion

After identifying an optimal FCCP exposure for cat ovarian tissue (200 nM for 120 min), our data demonstrated that FCCP pre-exposure followed by 2 days of culture protected and enhanced the follicle integrity. Even though this pre-exposure did not exert a beneficial effect during cryopreservation, it was clearly shown that it was not detrimental to the ovarian tissue.

Regulation of the metabolic activity of the cells or tissues has been widely examined to minimize the effects of external stress stimuli [15, 24, 25]. These studies explored the downregulation of the cellular metabolism by regulating ATP synthesis that occurs in the mitochondria via the oxidative phosphorylation. However, excessive reactive oxygen species generated concomitantly through that process also deteriorate cell structures and cause DNA damages. Oxidative stress also generally happen at the time of ovarian excision, during transportation, culture, or even the cryopreservation procedure [26, 27]. Mild mitochondrial uncoupling has also been studied in vivo to increase the longevity of individuals. Specifically, 2,4-dinitrophenol—a proton ionophore—was able to lower serological glucose, triglyceride, and insulin levels in serum and decrease reactive oxygen species levels and tissue DNA oxidation [28]. Here, we examined the mitigation of freezing stress on the ovarian tissue and the enclosed follicles that are critical for fertility preservation strategies [29–31]. Knowing that slow freezing procedures have resulted in most of the reports of live birth in human ovarian tissue cryopreservation followed by grafting [2, 32, 33], we investigated the cryopreservation method by using a protocol previously published [16].

In the first part of this study, we investigated the concentration and duration of the FCCP in pre-exposure in the ovarian tissue fragments by assessing the changes in mitochondrial membrane potential and follicular viability. Our observations confirmed that FCCP can depolarize the mitochondrial membrane potential within minutes [15, 20]. Importantly, transient depolarization (or “mild uncoupling”) of the mitochondrial membrane potential then can linger on for 30 min [15] or up to 72 h [19]. This phenomenon was shown to protect cells against toxicity [15]. However, higher concentrations of FCCP (1 μM or fivefold of the maximum concentration used in present study) can cause an irreversible depolarization of the mitochondrial membrane potential and result in the cell death after 24 h [34]. Follicular viability assessment showed that lower percentages of viability were obtained with 10 nM FCCP after 10-min incubation compared to 200 nM. This is consistent with reports showing that too low concentrations of FCCP can cause a detrimental hyperpolarization of the mitochondrial membrane [20]. Conversely, 100 nM FCCP for 30 min does not induce cellular damage [15]. All FCCP-treated tissues showed no difference in viability after longer incubations, but the viability in the 120-min control group (0 nM) had lower viability percentage than the 10-min control group. This clearly demonstrated that FCCP over the 120-min exposure had the potential to maintain the viability of the follicles within the ovarian tissue.

In the second set of experiments, in vitro culture of ovarian tissue was performed in order to better understand the effect of the FCCP pre-exposure in the cat ovarian tissues. The most significant result was a protective effect on preantral follicular viability at levels that were comparable to previous studies of multi-day culture in similar conditions [35]. After 2-day culture (except in the presence of 200 nM FCCP), percentages of morphologically normal follicles were lower within the tissue. This was not consistent with the observations of high and constant follicle viability, but the discrepancy (or overestimation of viable follicles) is frequently reported [17, 35]. Nevertheless, FCCP could not entirely protect the morphology of the tissues during in vitro culture. Even though apoptosis has been previously reported by our group after tissue culture [16], other studies have shown that FCCP exposures do not impact that natural phenomenon [36, 37].

Exposure to 200 nM FCCP had a protective effect on follicular density after 7 days of culture. This observation is similar to previous study of ovine ovarian tissue that found normal primordial follicle density after 6 days of culture [38]. Usually, a short period of 2 days is not enough to assess changes in the follicular density of follicular growth [38, 39]. However, the growth of follicles during the 7-day culture that we observed was in accordance with previous studies [40].

Percentages of proliferating follicles after FCCP exposures seemed to be lower than the fresh control. This can be explained by the fact that FCCP depolymerizes microtubules through the disruption of the mitochondrial proton gradient (increasing the intracellular pH) and decreasing the stability of microtubules as well as disrupting the centriole orientation during the cell division [41, 42].

In the last set of experiments, the pre-exposure to 200 nM FCCP for 120 min followed by 2 days of culture was chosen as a possible treatment before cryopreservation. The mitochondrial activity of the ovarian tissue was decreased after cryopreservation which is in agreement with previous studies on reproductive cells [43–45].

Follicular viability also was decreased after thawing which is similar to our previous study on cat ovarian tissue cryopreservation by using the same protocol [16]. Percentages of proliferating follicles were decreased in all cryopreserved tissues as well. This might be due to the impairment of the microtubule described in in vitro cultured or cryopreserved tissues in previous studies [46]. However, a former study reported better follicular proliferation after cryopreservation [47]. But, mild mitochondrial uncoupling has been shown to be detrimental to the cell proliferation [36, 48] which was consistent with the tissue pre-exposed to FCCP in the present study (only 6.4 proliferative preantral follicles per 1 mm2 tissue). Interestingly, the density of preantral follicles in cryopreserved tissues (cryopreserved control, 2-day culture control, and FCCP treatment group) was not different from the fresh group. This was actually better than in other studies showing the lower follicular density after cryopreservation [49, 50]. However, the high variations reported in each treatment group of our study are difficult to minimize as they are likely due to the different follicular pool in each individual [51].

This is the first study reporting the use and benefit of FCCP pre-exposure to the cat ovarian tissue. FCCP does not appear to exert a beneficial effect during cryopreservation, but further investigations are required to better understand and eventually take advantage of the absence of detrimental effect. Tissue pre-exposure to FCCP therefore was encouranging, but next studies may involve the addition of insulin, anti-apoptotic drugs, or superoxide dismutase supplementation to enhance the beneficial effect [38, 52, 53]. It would also be worth of exploring the AMPK pathway that plays a critical role in the mild uncoupling process of the mitochondria, ATP production, and reactive oxygen species production [15, 20]. Lastly, the technique of mild mitochondrial uncoupling also is successful in vivo to decrease reactive oxygen species levels and DNA oxidation. Thus, it might be interesting to treat animals or humans before collecting the ovarian tissue for fertility preservation [28].

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Asst. Prof. Dr. Sayamon Srisuwatanasagul for histologic technical assistance, Dr. Paweena Thuwanut for histologic interpretation advice and Assoc. Prof. Dr. Padet Tummaruk for helping with statistical analysis.

Compliance with ethical standards

Funding

Financial support for this work was provided by the Royal Golden Jubilee Ph.D. Program (PHD/0199/2552), the 90th Anniversary of Chulalongkorn University Fund (Ratchadaphiseksomphot Endowment Fund), and Research Unit of Obstetrics and Reproduction in Animals, Chulalongkorn University.

Footnotes

Capsule Uncoupling the oxidative phosphorylation of the domestic cat ovarian tissue with carbonyl cyanide 4-(trifluoromethoxy)phenylhydrazone (FCCP) is beneficial to the viability and morphology of follicles during ovarian tissue culture. However, tissue pre-exposure to FCCP does not have a protective or detrimental effect during cryopreservation.

References

- 1.Silber SJ. Ovary cryopreservation and transplantation for fertility preservation. Mol Hum Reprod. 2012;18:59–67. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gar082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Donnez J, Dolmans MM, Pellicer A, Diaz-Garcia C, Sanchez Serrano M, Schmidt KT, et al. Restoration of ovarian activity and pregnancy after transplantation of cryopreserved ovarian tissue: a review of 60 cases of reimplantation. Fertil Steril. 2013;99:1503–13. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wiedemann C, Hribal R, Ringleb J, Bertelsen MF, Rasmusen K, Andersen CY, et al. Preservation of primordial follicles from lions by slow freezing and xenotransplantation of ovarian cortex into an immunodeficient mouse. Reprod Domest Anim. 2012;47(Suppl 6):300–4. doi: 10.1111/rda.12081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jewgenow K, Paris MC. Preservation of female germ cells from ovaries of cat species. Theriogenology. 2006;66:93–100. doi: 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2006.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Songsasen N, Comizzoli P, Nagashima J, Fujihara M, Wildt DE. The domestic dog and cat as models for understanding the regulation of ovarian follicle development in vitro. Reprod Domestic Anim = Zuchthygiene. 2012;47:13–8. doi: 10.1111/rda.12067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Comizzoli P, Songsasen N, Wildt DE. Protecting and extending fertility for females of wild and endangered mammals. Cancer Treat Res. 2010;156:87–100. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-6518-9_7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wiedemann C, Zahmel J, Jewgenow K. Short-term culture of ovarian cortex pieces to assess the cryopreservation outcome in wild felids for genome conservation. BMC Vet Res. 2013;9:37. doi: 10.1186/1746-6148-9-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Higuchi CM, Maeda Y, Horiuchi T, Yamazaki Y. A simplified method for three-dimensional (3-D) ovarian tissue culture yielding oocytes competent to produce full-term offspring in mice. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0143114. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0143114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thuwanut P, Chatdarong K. Cryopreservation of cat testicular tissues: effects of storage temperature, freezing protocols and cryoprotective agents. Reprod Domest Anim. 2012;47:777–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0531.2011.01967.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cleary M, Snow M, Paris M, Shaw J, Cox SL, Jenkin G. Cryopreservation of mouse ovarian tissue following prolonged exposure to an Ischemic environment. Cryobiology. 2001;42:121–33. doi: 10.1006/cryo.2001.2315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Evecen M, Cirit U, Demir K, Karaman E, Hamzaoglu AI, Bakirer G. Developmental competence of domestic cat oocytes from ovaries stored at various durations at 4 degrees C temperature. Anim Reprod Sci. 2009;116:169–72. doi: 10.1016/j.anireprosci.2009.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li C, Jackson RM. Reactive species mechanisms of cellular hypoxia-reoxygenation injury. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2002;282:C227–41. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00112.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Menze MA, Chakraborty N, Clavenna M, Banerjee M, Liu XH, Toner M, et al. Metabolic preconditioning of cells with AICAR-riboside: improved cryopreservation and cell-type specific impacts on energetics and proliferation. Cryobiology. 2010;61:79–88. doi: 10.1016/j.cryobiol.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brennan JP, Southworth R, Medina RA, Davidson SM, Duchen MR, Shattock MJ. Mitochondrial uncoupling, with low concentration FCCP, induces ROS-dependent cardioprotection independent of KATP channel activation. Cardiovasc Res. 2006;72:313–21. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weisová P, Anilkumar U, Ryan C, Concannon CG, Prehn JHM, Ward MW. ‘Mild mitochondrial uncoupling’ induced protection against neuronal excitotoxicity requires AMPK activity. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1817;2012:744–53. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2012.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tanpradit N, Comizzoli P, Srisuwatanasagul S, Chatdarong K. Positive impact of sucrose supplementation during slow freezing of cat ovarian tissues on cellular viability, follicle morphology, and DNA integrity. Theriogenology. 2015;83:1553–61. doi: 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2015.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fujihara M, Comizzoli P, Keefer CL, Wildt DE, Songsasen N. Epidermal growth factor (EGF) sustains in vitro primordial follicle viability by enhancing stromal cell proliferation via MAPK and PI3K pathways in the prepubertal, but not adult, cat ovary. Biol Reprod. 2014;90:86. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.113.115089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martinez-Madrid B, Dolmans MM, Van Langendonckt A, Defrere S, Donnez J. Freeze-thawing intact human ovary with its vascular pedicle with a passive cooling device. Fertil Steril. 2004;82:1390–4. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2004.06.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Han YH, Kim SH, Kim SZ, Park WH. Carbonyl cyanide p-(trifluoromethoxy) phenylhydrazone (FCCP) as an O2(*-) generator induces apoptosis via the depletion of intracellular GSH contents in Calu-6 cells. Lung Cancer. 2009;63:201–9. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2008.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Perry SW, Norman JP, Barbieri J, Brown EB, Gelbard HA. Mitochondrial membrane potential probes and the proton gradient: a practical usage guide. Biotechniques. 2011;50:98–115. doi: 10.2144/000113610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cottet-Rousselle C, Ronot X, Leverve X, Mayol JF. Cytometric assessment of mitochondria using fluorescent probes. Cytometry A. 2011;79:405–25. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.21061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gan Z, Audi SH, Bongard RD, Gauthier KM, Merker MP. Quantifying mitochondrial and plasma membrane potentials in intact pulmonary arterial endothelial cells based on extracellular disposition of rhodamine dyes. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2011;300:L762–72. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00334.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kenngott RA, Vermehren M, Ebach K, Sinowatz F. The role of ovarian surface epithelium in folliculogenesis during fetal development of the bovine ovary: a histological and immunohistochemical study. Sex Dev. 2013;7:180–95. doi: 10.1159/000348881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Quarrie R, Lee DS, Reyes L, Erdahl W, Pfeiffer DR, Zweier JL, et al. Mitochondrial uncoupling does not decrease reactive oxygen species production after ischemia-reperfusion. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2014;307:H996–1004. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00189.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kenwood BM, Weaver JL, Bajwa A, Poon IK, Byrne FL, Murrow BA, et al. Identification of a novel mitochondrial uncoupler that does not depolarize the plasma membrane. Mol Metab. 2014;3:114–23. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2013.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Otala M, Erkkila K, Tuuri T, Sjoberg J, Suomalainen L, Suikkari AM, et al. Cell death and its suppression in human ovarian tissue culture. Mol Hum Reprod. 2002;8:228–36. doi: 10.1093/molehr/8.3.228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fabbri R, Sapone A, Paolini M, Vivarelli F, Franchi P, Lucarini M, et al. Effects of N-acetylcysteine on human ovarian tissue preservation undergoing cryopreservation procedure. Histol Histopathol. 2015;30:725–35. doi: 10.14670/HH-30.725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.da Silva Caldeira CC, Cerqueira FM, Barbosa LF, Medeiros MH, Kowaltowski AJ. Mild mitochondrial uncoupling in mice affects energy metabolism, redox balance and longevity. Aging Cell. 2008;7:552–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2008.00407.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Imbert R, Moffa F, Tsepelidis S, Simon P, Delbaere A, Devreker F, et al. Safety and usefulness of cryopreservation of ovarian tissue to preserve fertility: a 12-year retrospective analysis. Hum Reprod. 2014;29:1931–40. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deu158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meirow D, Roness H, Kristensen SG, Andersen CY. Optimizing outcomes from ovarian tissue cryopreservation and transplantation; activation versus preservation. Hum Reprod. 2015;30:2453–6. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dev210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang X, Catt S, Pangestu M, Temple-Smith P. Successful in vitro culture of pre-antral follicles derived from vitrified murine ovarian tissue: oocyte maturation, fertilization, and live births. Reproduction. 2011;141:183–91. doi: 10.1530/REP-10-0383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kawamura K, Cheng Y, Suzuki N, Deguchi M, Sato Y, Takae S, et al. Hippo signaling disruption and Akt stimulation of ovarian follicles for infertility treatment. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:17474–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1312830110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Suzuki N, Yoshioka N, Takae S, Sugishita Y, Tamura M, Hashimoto S, et al. Successful fertility preservation following ovarian tissue vitrification in patients with primary ovarian insufficiency. Hum Reprod. 2015;30:608–15. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deu353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brennan JP, Berry RG, Baghai M, Duchen MR, Shattock MJ. FCCP is cardioprotective at concentrations that cause mitochondrial oxidation without detectable depolarisation. Cardiovasc Res. 2006;72:322–30. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fujihara M, Comizzoli P, Wildt DE, Songsasen N. Cat and dog primordial follicles enclosed in ovarian cortex sustain viability after in vitro culture on agarose gel in a protein-free medium. Reprod Domest Anim. 2012;47(Suppl 6):102–8. doi: 10.1111/rda.12022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mlejnek P, Dolezel P. Loss of mitochondrial transmembrane potential and glutathione depletion are not sufficient to account for induction of apoptosis by carbonyl cyanide 4-(trifluoromethoxy)phenylhydrazone in human leukemia K562 cells. Chem Biol Interact. 2015;239:100–10. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2015.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Han YH, Park WH. Intracellular glutathione levels are involved in carbonyl cyanide p-(trifluoromethoxy) phenylhydrazone-induced apoptosis in As4.1 juxtaglomerular cells. Int J Mol Med. 2011;27:575–81. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2011.604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Henry L, Fransolet M, Labied S, Blacher S, Masereel MC, Foidart JM, et al. Supplementation of transport and freezing media with anti-apoptotic drugs improves ovarian cortex survival. J Ovarian Res. 2016;9:4. doi: 10.1186/s13048-016-0216-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sanfilippo S, Canis M, Romero S, Sion B, Dechelotte P, Pouly JL, et al. Quality and functionality of human ovarian tissue after cryopreservation using an original slow freezing procedure. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2013;30:25–34. doi: 10.1007/s10815-012-9917-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Khosravi F, Reid RL, Moini A, Abolhassani F, Valojerdi MR, Kan FWK. In vitro development of human primordial follicles to preantral stage after vitrification. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2013;30:1397–406. doi: 10.1007/s10815-013-0105-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Maro B, Marty MC, Bornens M. In vivo and in vitro effects of the mitochondrial uncoupler FCCP on microtubules. EMBO J. 1982;1:1347–52. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1982.tb01321.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Alieva IB, Vorobjev IA. Centrosome behavior under the action of a mitochondrial uncoupler and the effect of disruption of cytoskeleton elements on the uncoupler-induced alterations. J Struct Biol. 1994;113:217–24. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1994.1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yeste M, Estrada E, Rocha LG, Marin H, Rodriguez-Gil JE, Miro J. Cryotolerance of stallion spermatozoa is related to ROS production and mitochondrial membrane potential rather than to the integrity of sperm nucleus. Andrology. 2015;3:395–407. doi: 10.1111/andr.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jones A, Van Blerkom J, Davis P, Toledo AA. Cryopreservation of metaphase II human oocytes effects mitochondrial membrane potential: implications for developmental competence. Hum Reprod. 2004;19:1861–6. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lei T, Guo N, Tan MH, Li YF. Effect of mouse oocyte vitrification on mitochondrial membrane potential and distribution. J Huazhong Univ Sci Technol Med Sci. 2014;34:99–102. doi: 10.1007/s11596-014-1238-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kim SS, Kang HG, Kim NH, Lee HC, Lee HH. Assessment of the integrity of human oocytes retrieved from cryopreserved ovarian tissue after xenotransplantation. Hum Reprod. 2005;20:2502–8. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dei099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Isachenko V, Isachenko E, Mallmann P, Rahimi G. Increasing follicular and stromal cell proliferation in cryopreserved human ovarian tissue after long-term precooling prior to freezing: in vitro versus chorioallantoic membrane (CAM) xenotransplantation. Cell Transplant. 2013;22:2053–61. doi: 10.3727/096368912X658827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Guimaraes EL, Best J, Dolle L, Najimi M, Sokal E, van Grunsven LA. Mitochondrial uncouplers inhibit hepatic stellate cell activation. BMC Gastroenterol. 2012;12:68. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-12-68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Milenkovic M, Diaz-Garcia C, Wallin A, Brannstrom M. Viability and function of the cryopreserved whole rat ovary: comparison between slow-freezing and vitrification. Fertil Steril. 2012;97:1176–82. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.01.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Luyckx V, Scalercio S, Jadoul P, Amorim CA, Soares M, Donnez J, et al. Evaluation of cryopreserved ovarian tissue from prepubertal patients after long-term xenografting and exogenous stimulation. Fertil Steril. 2013;100:1350–7. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.07.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jewgenow K, Göritz F. The recovery of preantral follicles from ovaries of domestic cats and their characterisation before and after culture. Anim Reprod Sci. 1995;39:285–97. doi: 10.1016/0378-4320(95)01397-I. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Aguiar FL, Lunardi FO, Lima LF, Rocha RM, Bruno JB, Magalhaes-Padilha DM, et al. Insulin improves in vitro survival of equine preantral follicles enclosed in ovarian tissue and reduces reactive oxygen species production after culture. Theriogenology. 2016;85:1063–9. doi: 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2015.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kim EJ, Lee HJ, Lee J, Youm HW, Lee JR, Suh CS, et al. The beneficial effects of polyethylene glycol-superoxide dismutase on ovarian tissue culture and transplantation. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2015;32:1561–9. doi: 10.1007/s10815-015-0537-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]