Abstract

Background: The Dutch Public Health Status and Forecasts report (PHSF Report) integrates research data and identifies future trends affecting public health in the Netherlands. To investigate how PHSF contributions to health policy can be enhanced, we analysed the development process whereby the PHSF Report for 2010 was produced (PHSF-2010). Method: To collect data, a case study approach was used along the lines of Contribution Mapping including analysis of documents from the PHSF-2010 process and interviews with actors involved. All interviews were recorded and transcribed ad verbatim and coded using an inductive code list. Results: The PHSF-2010 process included activities aimed at alignment between researchers and policy-makers, such as informal meetings. However, we identified three issues that are easily overlooked in knowledge development, but provide suggestions for enhancing contributions: awareness of divergent; continuously changing actor scenarios; vertical alignment within organizations involved and careful timing of draft products to create early adopters. Conclusion: To enhance the contributions made by an established public health report, such as the PHSF Report, it is insufficient to raise the awareness of potential users. The knowledge product must be geared to policy-makers’ needs and must be introduced into the scenarios of actors who may be less familiar. The demand for knowledge product adaptations has to be considered. This requires continuous alignment efforts in all directions: horizontal and vertical, external and internal. The findings of this study may be useful to researchers who aim to enhance the contributions of their knowledge products to health policy.

Introduction

Public health status and forecasts report

The Dutch National Institute for Public Health and the Environment (Rijksinstituut voor Volksgezondheid en Milieu, RIVM) has published a Public Health Status and Forecasts Report (PHSF Report) every four years since 1993, most recently in 2014.1 The PHSF Report integrates research data on public health and identifies future trends in public health in the Netherlands.

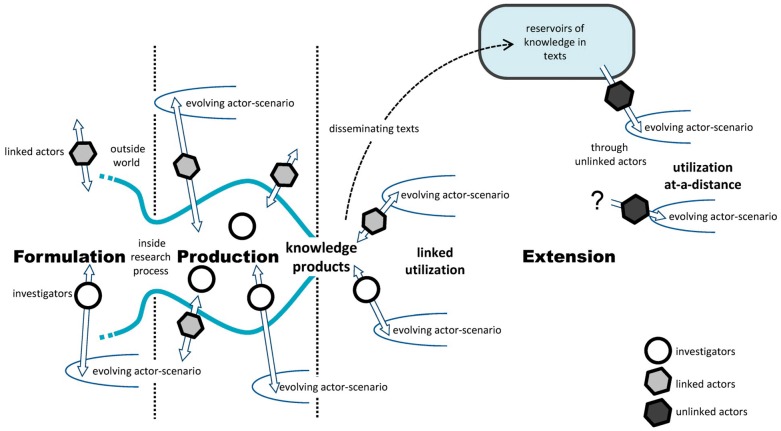

Since the first edition, both the format and the focus of the PHSF report have changed repeatedly, reflecting developments in public health. An important moment in PHSF history was the establishment of its official status in the policy cycle by the Dutch Public Health Act (Wet Publieke gezondheid) in 2002. The PHSF Report provides the policy themes for the next step in this cycle: the publication of the ‘National Health Memorandum’ by the Public Health department on behalf of the Minister of Health2 (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Public Health Policy Cycle in The Netherlands. The PHSF Report provides the policy themes for the National Health Memorandum of the Minister of Health by law. Local PHSF reports are the basis for health memoranda of the municipalities and are developed by Community Health Services in a comparable process as the national PHSF

Another interesting development is the translation of the national PHSF Report into local PHSF Reports by Community Health Services since 2006, in line with the decentralization of healthcare to municipality level in the Netherlands.3

Despite its established use for the National Health Memorandum, improvement of PHSF contributions to health policy-making is still an issue. It remains challenging to use the report as effectively as possible. Both RIVM and the Ministry of Health (MoH), Welfare and Sport want the PHSF Reports to serve as a knowledge base for policy-makers; not only for policy-makers of the PH department acting as the principal, but also for policy-makers of other MoH departments. For this study, we formulated the following research question: What improvements need to be made to the PHSF process in order to enhance PHSF contributions to national health policy in the broad sense?

Theoretical background

Science-policy relations have been described in a variety of theoretical models. Traditional ‘positivist’ models of knowledge utilization emphasize the importance of bridging the gap between the policy-making and research domains. Weiss’ typology of knowledge use in health policy contributed to awareness of the possible functions of knowledge products in policy-making; as a source of data, ideas or arguments.4 An important notion is that knowledge uptake is not as rational as is often assumed. In practice, policy-making is incremental in nature and is a highly complicated process involving many actors and levels of government. Theories on the complex policy process can help scientists who want to contribute to policy-making to understand the role of knowledge in that process.5–8 To address this complexity, interaction models for knowledge use have been developed that take into account the policy-makers’ needs and that focus on the interaction between researchers and policy-makers, as reflected in the model developed by De Goede, e.g.9 The ‘constructivist’ perspective goes a step further by considering knowledge as a social construct produced in a co-creation process.10, 11

PHSF process

The PHSF Report has been described as an example of a successful ‘boundary object’ developed through co-creation and connecting the science and health policy domains, while RIVM has been characterised as a ‘boundary organization’ in Guston’s terminology.11,12 A range of actors participate in the PHSF process, including RIVM scientists, policy-makers and scientists working in academia. RIVM scientists repeatedly interact with policy-makers in the PHSF Policy Advisory Group (PAG) during the development process. Increasing attention was devoted to alignment with stakeholders in successive PHSF processes. In her analysis of the PHSF Report as a boundary object, Van Egmond has pointed out the role of the PAG as a ‘backstage area’ where negotiations about the boundaries between science and policy-making take place.13 According to Goffman’s concept of ‘backstage work’ vs. ‘front stage presentation’, these informal negotiations enable the creation of an aligned knowledge product that is acceptable to both the commissioning client and the research organization and that can be officially presented to the outside world on ‘the front stage’.14

Study approach

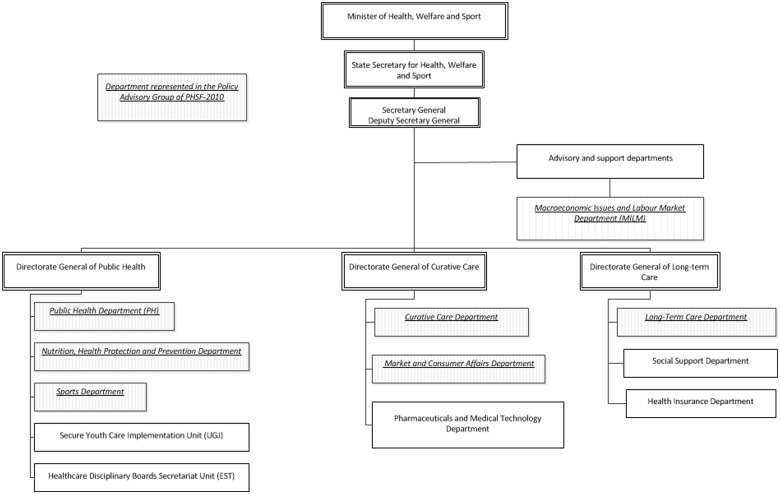

To complement the already existing insights, we intended to develop practical recommendations for researchers to improve the contributions made by the PHSF Report. De Leeuw has observed that ‘current perspectives (both Knowledge Translation and the Actor-Network Theory) do not reflect appropriately on actions that can be taken at the nexus between research, policy and practice in order to facilitate more integration’.15 Kok and Schuit16 have developed the Contribution Mapping (CM) approach for analyzing ‘how’ knowledge is converted into action. Kok and Schuit took the complexity of knowledge production into account and conceptualized knowledge utilization as so-called ‘contributions to action’. A contribution is made when knowledge is included in the ‘actor scenario’, representing the actor’s view of the future. Specific actions—so-called ‘alignment efforts’—can be undertaken to align with the relevant actor scenarios and to enhance the contributions of knowledge. To facilitate the analysis of alignment efforts, CM uses a three-phase model of knowledge production: a formulation phase to define the research question and approach, a production phase to conduct research, and an extension phase to disseminate the research results16 (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Three-Phase Model by Kok and Schuit.16 In the three-phase process model, investigators and linked actors interact during the research process. During the process, contributions to health policy can already be realized. The process narrows when the research approach is decided on. In the production phase, the process narrows again as knowledge products are realized. In the extension phase, the knowledge is disseminated.16 Published before in reference.16

By using the CM approach to analyse the PHSF-2010 process, we expected to gain detailed insights for the identification of areas that specifically require alignment efforts.

Methods

To collect data on the PHSF-2010 process, we used a case study approach that included analysis of documents related to the PHSF-2010 process and in-depth semi-structured interviews with involved key actors at both RIVM and MoH who were able to survey the process at different organizational levels.17 Two RIVM researchers conducted the interviews with RIVM experts and managers involved in the PHSF-2010 process in 2011 (n = 10). An independent researcher (not working at RIVM) conducted the interviews with policy-makers and managers at the MoH in 2013 (n = 10). All interviews were conducted using a list of topics based on the theoretical framework (Supplementary Materials), and were recorded and transcribed ad verbatim. We coded the interviews in the Atlas ti 7.1.3 software package using a deductive code list that was based on the theoretical framework and inductively supplemented based on extensive and iterative analysis of the interviews. In an open coding session, three researchers discussed the coding of two interviews until consensus was reached. We identified areas for alignment efforts using a constant comparative analysis method.18

We operationalized the CM concepts as follows:

‘Actor scenario’: actor’s view of health policy future and/or his/her professional future

‘Alignment efforts’: opportunities for actions taken by RIVM scientists, policy-makers and managers of both RIVM and MoH to align the PHSF-2010 Report with the needs of the MoH

Knowledge’: the integration of research data on public health for the purpose of the PHSF-2010 Report, the PHSF-2010 Reports (knowledge products), and the exchange of knowledge through interaction between actors

‘Contribution (to action)’: any indication that PHSF knowledge was included in an actor scenario

‘Formulation phase’: period for defining the PHSF-2010 scope (2006–7)

‘Production phase’: period between agreement on the PHSF-2010 scope and the publication of the PHSF-2010 reports (2008–10)

‘Extension phase’: period after publication in 2010, evaluated until 2013

Results

Alignment in the formulation phase

In the Formulation Phase, RIVM aligned with the policy-makers of the Public Health department about the course to take and agreed to develop a main report and four thematic reports, all to be delivered in 2010.

Until 2006, the PHSF Report was mainly used by the PH department. Both RIVM and PH policy-makers expected that co-financing by other departments would be favourable for involving them more directly in the PHSF process and strengthening PHSF contributions in the broader health policy domain. For the first time, the Macroeconomic Issues and Labour Market Department (MILM) provided a budget that was used to develop a thematic report on the societal benefits of healthcare.19

Alignment in the production phase

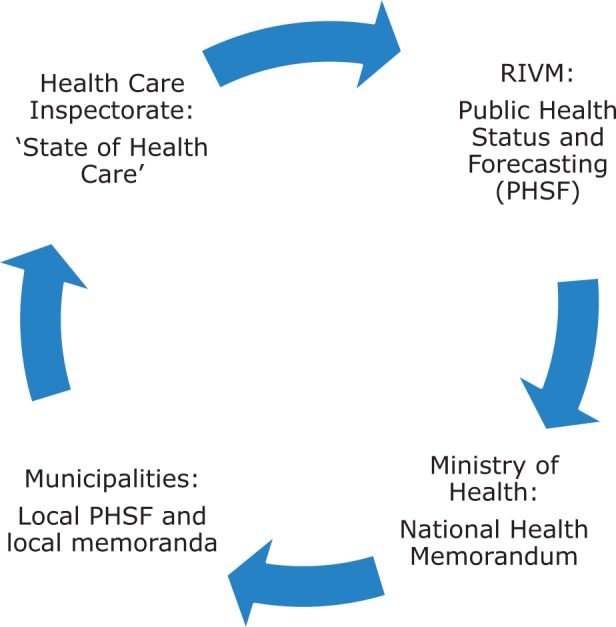

Once the Production Phase started, the PAG was formed with senior policy-makers of the relevant MoH departments (figure 3)

Figure 3.

Organization Chart of the MoH, Welfare and Sport in the Netherlands. The departments indicated in italic underlined characters were represented in the PAG of the PHSF-2010 process.

The RIVM project managers regularly consulted the PAG and experienced that different departments had varying views and needs. The PH director, who also served as the PAG chair, challenged RIVM to describe implications for health policy. His opinion was that facts need interpretation to contribute to policy-making: ‘If RIVM only publishes reports that provide facts, but do not reflect upon the implications, the policy impact of the document will be zero and it will be ignored. So it needs to provide a trigger … that is the art of balancing, you should not cross the line, but you have to provide a trigger and ensure that the message is not lost.’ However, MILM policy-makers appeared not to be in favour of near-to-policy statements by RIVM and as new co-financier, they interfered in discussions about the content of the PHSF-2010 Report. For example, the interpretation of socio-economic health inequalities (SEHIs), a highly political issue, appeared to be controversial. As one policy-maker mentioned: ‘I argued over that issue (the draft text on SEHIs) with X (RIVM researcher) by phone, since I believed that the text contained too many political opinions.’

Due to time constraints, the thematic reports were completed at the last minute just before the strict deadlines. The PAG members had hardly any time to read the drafts, hindering discussion on the content. According to a PAG member, this resulted in a missed opportunity for alignment: ‘We finally received the thematic reports, which contained hundreds of pages, at the last minute. In the first place, this gave us the feeling that we could not make any changes or recommendations, since the process was already completed and the reports were already finished. In the second place, this also influenced the impact of the thematic reports later on (….). If the PAG members, the ‘early adopters’, discuss the reports, then it will sink in properly and that will lead to further dissemination.’ Timely delivery of knowledge products is a well-known factor for successful contributions. Although the PHSF-2010 Report was completed in time, we found that timely draft versions are also important to take full advantage of backstage opportunities in order to create support and enhance contributions.

RIVM professionals recognized that familiarity with the MoH organization is important for successful alignment. As one researcher said: ‘I think you need to know how things work at the Ministry of Health. You need to know what they are dealing with. You need to understand their issues, without fully identifying with them.’ One respondent left RIVM and joined the Ministry of Health and found out that he did not know the Ministry as well as he thought he did: ‘When I worked at RIVM, I thought I knew how things worked (at the Ministry). However, when I myself was employed by the Ministry for four-and-a-half years, I discovered that in fact I knew very little about it. (….) I had never realized that before, because at RIVM I was one of the few people who maintained very close contacts with the Ministry. People thought I knew what went on there.’ This finding underlines the need for continuous attention to evolving actor-scenarios and policy-makers’ needs.

Another important finding was that effective alignment requires consistent alignment efforts at every hierarchic level, as well as conscious vertical alignment within the involved organizations. Since the PHSF is the formal starting point for the National Health Memorandum, alignment at all hierarchical levels between RIVM and MoH should be a matter of course. However, coordination was lacking due to limited internal alignment. The RIVM project managers acted independently in line with the RIVM matrix structure, while senior management remained distant.

Alignment in the extension phase

The ‘front stage’ presentation of the PHSF Report to the Minister took place at an event where the Health Care Inspectorate’s ‘Staat van de Gezondheidszorg 2010’ Report (State of Health Care-2010) was also presented. Immediately afterwards, senior RIVM management misrepresented the PHSF-2010 message to the press by confusing it with the Inspectorate’s message. This was caused by insufficient familiarity with the PHSF-2010 content as a result of lacking vertical alignment. Articles appeared in the press claiming that the report had recommended ‘strong government measures to promote a healthy lifestyle’, and had concluded that ‘many preventive health campaigns are ineffective’. These messages conflicted with the intended optimistic PHSF-2010 messages as aligned with the MoH. The media reports caused inconvenience for MoH policy-makers and they experienced difficulties in obtaining funding for preventive campaigns for some time. One policy-maker complained: ‘There was no attention paid to the PHSF messages and for about six months to a year, we had to repair the situation with Parliament.’

After publication, the focus at the MoH quickly shifted from the PHSF Report to the issues of the day. Alignment during the production phase is regarded as important for early knowledge transfer and the creation of ‘early adopters’. However, many of the key actors (coincidentally) changed in the PHSF-2010 extension phase. This included several PAG representatives, the PHSF project managers and senior managers (both at RIVM and MoH). Their successors were less involved in the PHSF-2010 process or not involved at all, which illustrates the ongoing need for alignment efforts in the extension phase although hardly any budget was available for these activities. As one policy-maker put it: ‘RIVM should work together with the PAG and should carefully examine how best to promote the PHSF Report both within and outside the MoH after the report’s presentation. We should remind people where and how to find the report, and how it might be valuable to them.’

Contributions to policy-making

The PHSF-2010 Report made a key contribution to the National Health Memorandum published in 2011,2 and both PH policy-makers and RIVM project managers were very pleased with this. As one project leader put it: ‘I am pleased with the contribution to the Memorandum. Of course, there are always points for improvement. However, the basic PHSF-2010 issues and ideas were included.’

The PHSF-2010 contributions to other health policy domains were less self-evident than RIVM expected. Some PAG members indicated that they personally appreciated the PHSF-2010 Report for the overall picture it provided of the public health situation, but that their department needed information the PHSF-2010 Report did not offer, such as more specific figures and facts. One policy-maker said: ‘They (RIVM) have all sorts of products and are very supply-oriented. It’s as if they want to draw attention to their allegedly amazing products without really knowing who they are talking to. To put it frankly, they imply that you would be stupid not to use their data and products. However, in my view, you have to approach it the other way round. I don’t have to use those products at all. I just need access to the right information, and their task is to help me in whatever way possible.’ Researchers must realize that actors have their own actor scenarios which may have implications for the process, the concept, and the format of the knowledge to be produced. This again underlines the importance of thorough familiarity with the target group, which requires a combination of horizontal and vertical alignment efforts.

Discussion

Study limitations

Because the interviews were conducted in retrospect, recollection bias may have played a role. However, we noted that the interview structure and the Three-Phase Model facilitated recollection. Furthermore, documents, such as minutes of PAG meetings and the PHSF-2010 evaluation report were used for triangulation purposes in combination with the interviews. The number of interviewees and the representation of all hierarchical levels amongst respondents were sufficient to gain a good overview of the research process.

Reflections on the CM approach

We used CM to analyze how alignment influenced the PHSF Report’s contributions to health policy-making. The analysis required a lot of time, making it unfeasible for routine evaluation of research projects. However, we gained useful insights that are generally applicable, both in our own organization and in other comparable knowledge institutes. We secured our findings for the RIVM organization by designing a tool to support researchers in reflecting on the research process, taking into account the important areas for alignment efforts. A research article on this tool is currently being prepared.

Conclusions

The analysis of the PHSF-2010 process using the CM approach produced several recommendations for improving the contributions of the PHSF Report to health policy-making. The PHSF-2010 process included intensive alignment efforts, such as interaction in PAG meetings. However, we noticed three issues that need careful and specific alignment efforts:

Actors and their own needs: organizational environment

To be able to decide what needs to be done to enhance contributions, researchers must explore the actor scenarios of key actors. Since individuals can have a major impact and actors change all the time, the analysis has to be updated on a regular basis to make sure new scenarios are included.

Involvement of all hierarchical levels: vertical alignment

To steer the process in the right direction and to create the support needed, monitoring of adequate vertical alignment is essential. We already noticed this issue in two other case studies and it is clearly an ongoing challenge to manage vertical alignment for large, hierarchical organizations like RIVM and MoH.20,21

Creation of early adopters: timing of draft products

Policy-makers need sufficient opportunities to comment on draft knowledge products to enable them to become ‘early adopters’. This requires thorough process management and researchers should consider spending part of their research budget for this purpose.

Regular actor scenario analyses, ongoing vertical alignment and timely draft products are issues not exclusively related to the PHSF-2010 process, but also generally applicable to the process of many other reports for policy support; also at other governance levels and even in other countries. The general lesson to be learned from this study is that it is not enough to raise awareness of a well established knowledge product in order to enhance its contributions to policy-making. This requires also regular exploration of the actor scenarios of (sometimes less familiar) actors, and consideration of necessary knowledge product adaptations. And in turn, this process will require alignment efforts in all directions: horizontal and vertical, external and internal.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at EURPUB online.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Peter Schouten, MSc for his contribution to our project during his internship for his master degree in Management, Policy Analysis and Entrepreneurship in Health and Life Sciences at RIVM in 2011. We also thank Jolanda Keijsers, PhD for her input in the project team Improving Knowledge Utilization. We wish to thank all interviewees from the Ministry of Health and RIVM for their kind cooperation.

Funding

This work was supported by the Strategic Research Programme 2011-2014 of the National Institute for Public Health and the Environment in The Netherlands (project number S/270206).

Conflicts of interest: None declared.

Key points

It is not enough to raise awareness of a well established knowledge product in order to enhance its contributions to policy-making.

The Dutch PHSF Report requires specific alignment efforts on three issues to enhance its contributions.

The issues in question are: actor scenarios, vertical alignment and timely delivery of draft reports.

Alignment on these issues will also be useful for other health reports.

References

- 1.Hoeymans N, Van Loon AJM, Van den Berg M, et al. Een gezonder Nederland, kernboodschappen van de Volksgezondheid Toekomst Verkenning 2014. (Towards a healthier Netherlands. Key findings of the PHSF-2014) 2014.

- 2.Ministry of Public Health Welfare and Sport. Landelijke Nota Gezondheidsbeleid “Gezondheid Nabij” (National Health Memorandum “Health Nearby”). The Hague, The Netherlands 2011.

- 3.De Goede J, Steenkamer B, Treurniet H, et al. Public health knowledge utilisation by policy actors: an evaluation study in Midden-Holland, the Netherlands. Evid. Policy 2011;7:7–24. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weiss C. Policy research: data, ideas or arguments? In: Wagner P, Weiss CH, Wittrock B, Wollman H. editors. Social Sciences and Modern States. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kingdon J. Agendas, Alternatives, and Public Policies, 2nd edn New York: Longman, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sabatier P. Theories of the Policy Process, 2nd edn Boulder, Colorado, USA: Westview Press, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sabatier PA. An advocacy coalition framework of policy change and the role of policy-oriented learning therein. Policy Sci 1988;21:129–68. [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Leeuw E, Clavier C, Breton E. Health policy-why research it and how: health political science. Health Res Policy Syst 2014;12:55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Goede J, Putters K, van der Grinten T, van Oers HA. Knowledge in process? Exploring barriers between epidemiological research and local health policy development. Health Res Policy Syst 2010;8:26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wehrens R. Beyond two communities -from research utilization and knowledge translation to co-production? Public Health 2014;128:545–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bekker M, van Egmond S, Wehrens R, et al. Linking research and policy in Dutch healthcare: infrastructure, innovations and impacts. Evid Policy 2010;6:237–53. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guston DH. Boundary organizations in environmental policy and science: an introduction. Sci Technol Hum Values 2001;26:399–408. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van Egmond S, Bekker M, Bal R, van der Grinten T. Connecting evidence and policy: bringing researchers and policy makers together for effective evidence-based health policy in the Netherlands: a case study. Evid Policy 2011;7:25–39. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goffman E. The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. London: Penguin, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Leeuw E, McNess A, Crisp B, Stagnitti K. Theoretical reflections on the nexus between research, policy and practice. Crit Public Health 2008;18:5–20. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kok MO, Schuit AJ. Contribution mapping: a method for mapping the contribution of research to enhance its impact. Health Res Policy Syst 2012;10:21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yin RK. Case Study Research Design and Methods, 4th revised edition. Thousands Oaks: California, SAGE Publications Inc, 2008. ISBN: 9781412960991. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pope C, Ziebland S, Mays N. Analysing qualitative data. Br Med J 2000;320:114–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Post NAM, Zwakhals SLN, Polder JJ. Maatschappelijke baten. Deelrapport van de VTV 2010 Van gezond naar beter (Social Benefits. Thematic Report of PHSF-2010 'Towards better health'). RIVM Report. Bilthoven, The Netherlands, 2010.

- 20.Hegger I, Janssen S, Keijsers J, et al. Analyzing the contributions of a government-commissioned research project: a case study. Health Res Policy Syst 2014;12:8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hegger I, Marks LK, Janssen SW, et al. Enhancing the contribution of research to health care policy-making: a case study of the Dutch Health Care Performance Report. J Health Serv Res Policy 2016;21:29–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.