Abstract

Mutation breeding is based on the induction of genetic variations; hence knowledge of the frequency and type of induced mutations is of paramount importance for the design and implementation of a mutation breeding program. Although γ ray irradiation has been widely used since the 1960s in the breeding of about 200 economically important plant species, molecular elucidation of its genetic effects has so far been achieved largely by analysis of target genes or genomic regions. In the present study, the whole genomes of six γ-irradiated M2 rice plants were sequenced; a total of 144–188 million high-quality (Q>20) reads were generated for each M2 plant, resulting in genome coverage of >45 times for each plant. Single base substitution (SBS) and short insertion/deletion (Indel) mutations were detected at the average frequency of 7.5×10−6–9.8×10−6 in the six M2 rice plants (SBS being about 4 times more frequent than Indels). Structural and copy number variations, though less frequent than SBS and Indel, were also identified and validated. The mutations were scattered in all genomic regions across 12 rice chromosomes without apparent hotspots. The present study is the first genome-wide single-nucleotide resolution study on the feature and frequency of γ irradiation-induced mutations in a seed propagated crop; the findings are of practical importance for mutation breeding of rice and other crop species.

Keywords: Mutation breeding, γ rays, Mutation spectrum, Genomic variation

1. Introduction

Since the 1960s, γ ray irradiation has been used widely as an efficient tool for mutation induction in about 200 economically important plant species (http://mvd.iaea.org). A great number of mutants have been generated for genetic studies and for breeding of new varieties, which have been grown in areas up to billions of hectares (Ahloowalia et al., 2004). In the last century, numerous studies were carried out at the cytological and phenotypic levels with the aim of assessing the genetic effect of γ irradiation. Since the beginning of this century, molecular genetic tools have been adopted to characterize mutations induced by physical and chemical mutagens, which has revealed features of induced mutations and the estimation of mutation frequency in various plants (Nawaz and Shu, 2014). However, molecular genetic analysis is only suitable for characterizing mutations in selected genes or genomic regions of limited size. New technical platforms are required for revealing the full picture of induced mutations at the whole genome level.

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) technology, because of its high throughput and cost effectiveness, is appropriate for holistically examining genetic variations across the whole genome. For example, NGS-based analysis has been used for examining genetic variations in transgenic rice plants (Kawakatsu et al., 2013; Endo et al., 2015) and for investigating the molecular spectrum of somaclonal variation in regenerated rice (Miyao et al., 2012). Recently, NGS techniques were also used to study the frequency and type of spontaneous (Ossowski et al., 2010) and induced mutations, i.e. fast neutron mutagenesis in Arabidopsis (Belfield et al., 2012), ethyl methanesulfonate in lotus (Mohd-Yusoff et al., 2015), and γ irradiation in poplar (Henry et al., 2015).

Rice is one of the most important staple crops and a plant model for functional genomics studies. Rice mutation breeding has been especially successful, with more than 400 varieties being developed worldwide (http://mvd.iaea.org). Rice mutant varieties, either directly developed by γ irradiation or derived from important mutant varieties, have been grown on tens of millions of hectares (Ahloowalia et al., 2004). To reveal the feature of mutations induced by γ irradiation, Morita et al. (2009) sequenced selected mutant genes and observed small deletion being the most frequent mutation type. Analysis of mutant genes cloned by forward genetics also revealed similar results (Nawaz and Shu, 2014). To date, there is no report on the whole genome analysis of mutants induced by γ rays. We sequenced the genomes of six γ-irradiated M2 rice plants with the aim of finding the frequency, type, and feature of mutations induced by γ rays in a model plant species.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Generation and characterization of mutant populations

In 2010, a single plant of the rice (Oryza sativa L.) cultivar Nipponbare was chosen as the starting material (generation P0) of the present experiment. In 2011, seeds harvested from this plant were grown into a small population, from which seeds (generation P1) were harvested and used for γ ray (137Cs) irradiation at the Irradiation Centre of the Zhejiang Academy of Agricultural Sciences (Hangzhou, China). Three doses (150, 250, and 350 Gy given at a dose rate of about 1 Gy/min) were applied to dried seeds. Subsequent measurement using a ferrous sulfate dosimeter (Pettersson and Hettinger, 1967) revealed the actual absorbed doses as 165, 246, and 389 Gy, respectively.

In 2012, the irradiated seeds (P1M1) were sown after germination on a seedling bed, together with untreated controls; eighty seedlings for each dose were individually transplanted for the development of mutated populations in the experimental farm of Zhejiang University, Zijingang Campus (Hangzhou, China). Seeds (generation P2M2) were harvested from P1M1 plants on a panicle basis (five panicles per plant). To assess the effect of γ irradiation on the fertility, seed set rates were examined for 10 P1M1 plants per dose.

In 2013, P2M2 seedlings were grown on panicle rows in the experimental farm of Zhejiang Zhijiang Seed Co. (Yuhang, Hangzhou, China). Chlorophyll (Chl)-deficient mutants (albino, yellow) were observed 14 d after sowing and the mutation frequency was calculated on a panicle basis, i.e. the percentage of panicle rows with Chl-deficient seedlings. P2M2 populations were raised by transplanting 24 plants per panicle row in paddy fields, together with control plants. At the mature stage, P2M2 plants were inspected visually for morphological and fertility mutations. In each of the three P2M2 populations, two panicle rows were identified, one having a few plants with a mutant phenotype with the others having the wild-type (WT) phenotype, and one with plants that all had the WT phenotype. Then, one plant with a mutant phenotype from each of the panicle rows with mutant plants and one plant from each of the WT panicle rows were chosen and subjected to genotyping using 24 simple sequence repeat (SSR) markers according to Peng et al. (2003). Consequently, the three plants with a mutant phenotype, i.e. 165-MS, 246-MS, and 389-MS, and the three plants with no discernible mutant phenotype, i.e. 165-NP, 246-NP and 389-NP, were chosen for genome sequencing (Table 1).

Table 1.

Phenotypes and absorbed doses of γ rays of six sequenced P2M2 plants

| P2M2 plant | γ ray dose (Gy) | Phenotype |

| 165-MS | 165 | Plant exhibited empty and smaller (about 60% of Nipponbare) grains, and dwarfism (about half plant height of Nipponbare at maturity) |

| 165-NP | 165 | No discernible mutant phenotype |

| 246-MS | 246 | Plant exhibited empty grains while their grain sizes and plant heights were similar to those of Nipponbare |

| 246-NP | 246 | No discernible mutant phenotype |

| 389-MS | 389 | Plant exhibited empty grains and slightly shorter plant height (about 1/4 shorter compared to that of Nipponbare) |

| 389-NP | 389 | No discernible mutant phenotype |

In 2014, P3M3 plants of the three sequenced P2M2 plants without a discernible mutant phenotype, and WT sibling plants of the three sterile/dwarf P2M2 mutant plants, were grown in the experimental farm of the Jiaxing Academy of Agricultural Sciences (Jiaxing, China) and used to investigate mutation inheritance.

2.2. Genome sequencing and bioinformatics analysis

Genomic DNAs were extracted from leaf tissues by a modified CTAB (cetyltrimethylammonium bromide) method (Zheng et al., 2014) and fragmented to about 500 bp by a DNA ultrasonic disruptor (Covaris, Massachusetts, USA) to construct sequencing libraries, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Short paired-end (PE) reads (100 bp) were generated using the Illumina HiSeq2000 sequencing platform by Novogene Bioinformatics Technology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). Raw reads were pre-processed to remove adaptors and low-quality reads (≥50% of their nucleotides with quality value ≤5E). E-corrections were performed with the program “Correction” to further reduce the low-frequency k-mers (Li et al., 2009). Furthermore PE reads with N contents of >10% on one side were also removed. The clean data have been deposited in GenBank (BioProject ID: PRJNA296568).

The clean data were mapped to the Oryza sativa L. cv. Nipponbare reference genome v7.0 (ftp://ftp.ensemblgenomes.org/pub/plants/release-21/fasta/oryza_sativa/dna) using BWA v0.5.9 (Li et al., 2009). Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and short insertions/deletions (Indels) (up to 50 bp) were reported by SAMtools v0.1.18 (Li et al., 2009). The following filters were used to reduce the error rates of SNPs and Indels: a target depth of >15 and a target minimum mapping quality of 20. SNPs and Indel loci having more than four reads different from the remaining reads were defined as heterozygous, otherwise they were homozygous. All mutations were further annotated by ANNOVAR (Annotate Variation) (Wang et al., 2010). The SNPs detected between M2P2 plants and the reference Nipponbare consist of the differences between the reference Nipponbare and the Nipponbare seed in the present study, and for simplicity, SNPs are referred to as the single base substitution (SBS) mutations induced by irradiation hereafter.

Structural variations (SVs), i.e. insertion, deletion, inversion, intra-chromosomal translocation (ITX), and inter-chromosomal translocation (CTX), were reported by BreakDancer v1.1 (Chen et al., 2009), based on PE reads (>4) mapping to the reference genome. Copy number variations (CNVs) were detected by CNVnator, which is based on the statistical analysis of read depth (RD) (Abyzov et al., 2011). For this purpose, the whole genome was first divided into non-overlapping bins of 100 bp and the count of mapped reads within each bin was used as the final RD signal after correction for GC-bias.

2.3. Verification of identified mutations

The presence of mutations revealed by genome sequencing was further examined by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis of the 389-NP and 389-MS plants. For SBSs, a total of 20 exonic mutations were randomly selected; site-specific primers were designed and used to amplify fragments encompassing the mutations (Table S1). PCRs were performed in 50 µl volumes with 100 ng of genomic DNA, 25 µl of 2× master mix (containing 2× PCR buffer, 4 mmol/L MgCl2, 0.4 mmol/L deoxyribonucleoside triphosphates (dNTPs), 50 U/ml of Taq DNA polymerase; TOYOBO Co., Ltd.), and 1 µl each of 10 μ mol/L primers. The following generalized PCR profile was used: 5 min at 94 °C; followed by 35–40 cycles of 30 s at 94 °C, 30 s at 49–58 °C, and 30–90 s at 72 °C; with a final extension at 72 °C for 8 min. The cycle number and annealing temperature were optimized for amplification of the respective fragments. The amplicons were separated on a 1.0% agarose gel and target DNAs were recovered using a DNA gel extraction kit (Axygen Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Hangzhou, China) for Sanger sequencing by Shanghai Ruidi Biological Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Similarly, a total of 40 exonic Indel mutations within non-repetitive sequences (Indels 1–20 and Indels 31–50) and 20 within repetitive sequences (Indels 21–30 and Indels 51–60) were randomly selected for Sanger sequencing (Table S2).

Verification of SVs was performed for three insertions, five deletions, and two inversions, using site-specific primers designed to amplify fragments around the rearranged regions (Table S3). PCRs were performed in 20-µl volumes and the amplicons were separated on 1.0% agarose gels, followed by detection with ethidium bromide (for insertions and deletions) or by Sanger sequencing (for inversions).

Seven CNV mutations were randomly selected, and site-specific primers were designed and used to amplify fragments in the mutated sequence (Table S4). CNV mutations were verified by quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) using SYBR Green GoTaq® qPCR Master Mix Kit (Promega, USA) in a 10-μl volume with 50 ng of genomic DNA in 1× GoTaq® qPCR Master Mix (containing PCR buffer, MgCl2, dNTPs, Taq DNA polymerase), and 0.5 μ mol/L of each primer. The following program was used for all qPCRs: 10 min at 95 °C; and 40 cycles of 10 s at 95 °C, 30 s at 55 °C, and 30 s at 72 °C. Relative gene copy number was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCT method, with the rice actin gene as the internal standard (Lu et al., 2015).

To test whether the mutations identified in P2M2 plants could be transmitted into the M3 generation, five M2 sibling plants of 389-MS were grown into five P3M3 lines and examined for the presence of seven mutations (two SBSs and five Indels; Tables S1 and S2). Genomic DNAs were extracted from 32 plants of each P3M3 line and subjected to high-resolution melting (HRM) curve analysis, according to Tan et al. (2013). In brief, PCRs were performed in a 10-µl volume with 25 ng of DNA, 5 µl of 2× master mix (TOYOBO Co., Ltd.), 0.2 µl each of 10 µmol/L primers, and 1 µl of 10× EvaGreen (Biotium, USA), covered with a drop of mineral oil. HRM analysis was performed on a Lightscanner (Idaho Technology Inc., USA) and data were analyzed using its proprietary software, Call ITTM 2.0. The WT Nipponbare was used as a reference and samples with relative fluorescence differences (ΔF) of >0.05 were considered to be significantly different from Nipponbare (Hofinger et al., 2009).

All PCR primers were designed according to the genome sequence of rice cultivar Nipponbare (http:// www.gramene.org), using Primer Premier 5 software. All PCR primers were synthesized by Shanghai Sangong Biological Engineering Technology & Services Co., Ltd., China.

3. Results

3.1. Selection and sequencing of P2M2 plants

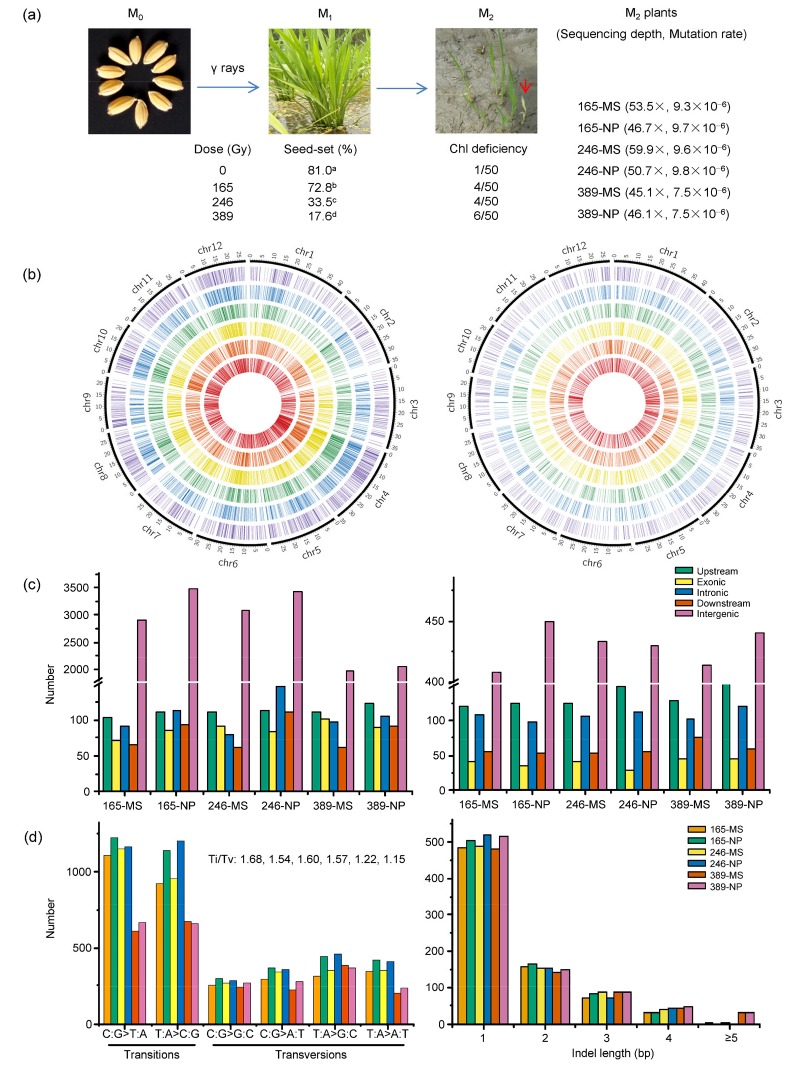

γ irradiation had a significant effect on seedling growth, reproduction of M1P1 plants, and mutagenesis of P2M2 plants. With increasing irradiation dose, the seed-set of P1M1 plants was reduced significantly to as low as 17.6%, and the frequency of Chl-deficient mutations reached 12% in P2M2 on a panicle-row basis (Fig. 1a).

Fig. 1.

γ ray mutagenesis and genome-wide profiling of induced mutations in rice

(a) Treatment of rice seeds with γ rays at three absorbed doses: 165, 246, and 389 Gy. The effects of γ rays on seed-set in P1M1 and chlorophyll (Chl)-deficient mutation rates (the number of panicle rows with Chl-deficient seedlings among the total of 50 panicle rows at each dose) in P2M2 are shown. A red arrow indicates an albino seedling in one of the P2M2 panicle rows at the seedling stage. Six P2M2 plants (165-MS, 165-NP, 246-MS, 246-NP, 389-MS, and 389-NP) were selected for sequencing, with the sequencing depth and mutation rate per site of each plant shown within parentheses. Seed-set rates with different letters indicate significant difference (P<0.05) among P1M1 populations. (b) Distribution of mutations across 12 chromosomes in the genomes of the six P2M2 plants, which, from outside to inside, are 165-MS, 165-NP, 246-MS, 246-NP, 389-MS, and 389-NP, respectively. Each radiating line stands for a mutation position of a single base substitution (SBS) (left) or an insertion/deletion (Indel) (right). (c, d) Molecular spectra of γ ray-induced mutations: (c) frequencies of substitution (left) and Indel (right) mutations located in the different genomic regions of the six P2M2 plants; (d) frequencies of specific types of SBS with the transitions/transversions (Ti/Tv) ratios shown in sequence (left), and frequencies and sizes of Indel mutations identified (right) in the six P2M2 plants

SSR genotyping of the selected six P2M2 plants showed that they all had a genotype identical to that of Nipponbare (Fig. S1); therefore, the possibility that they were off-type plants (mixtures or out-crossed plants) was excluded.

A total of 144–188 million high-quality (Q>20) reads was generated for the six P2M2 plants, i.e. 165-MS, 165-NP, 246-MS, 246-NP, 389-MS, and 389-NP. The sequence reads were mapped to the Nipponbare reference genome, resulting in genome coverage of > 45 times for each plant (Fig. 1a).

3.2. Single base substitution and short Indel mutations

SBSs and short Indels were detected between the genomes of the P2M2 plant and Nipponbare. After removing the mutations common to any two P2M2 plants, which were likely to have resulted from the genome differences between the progenitor Nipponbare at P1 generation used in the present study and the Nipponbare used for reference genome sequencing, a total of 2349 to 3915 SBSs and 752 to 834 Indels were identified in the six plants (Table 2).

Table 2.

Number and nature of single base substitutions (SBSs) and short insertion/deletion (Indel) mutations identified by next-generation sequencing (NGS) and bioinformatics analysis in the six γ ray-mutagenized plants

| P2M2 plant | Total number of SBS and Indel mutations | SBS |

Insertions (In) and deletions (Del) |

||

| SBS number (Hom/Het)1 | Exonic mutation (Syn/Nonsyn)2 | Indel number (Hom/Het)3 | Exonic mutation (frame-/nonframe-shift)4 | ||

| 165-MS | 4009 | 3257 (347/2910) | 71 (26/45) | 752 (649/103) (126/626) | 41 (15/26) |

| 165-NP | 4698 | 3915 (417/3498) | 87 (27/60) | 783 (665/118) (115/668) | 36 (13/23) |

| 246-MS | 4209 | 3437 (324/3113) | 91 (27/64) | 772 (657/115) (108/664) | 41 (16/25) |

| 246-NP | 4692 | 3899 (484/3415) | 84 (25/59) | 793 (690/103) (97/696) | 29 (9/20) |

| 389-MS | 3135 | 2349 (330/2019) | 102 (40/62) | 786 (681/105) (118/668) | 46 (11/35) |

| 389-NP | 3326 | 2492 (356/2136) | 89 (31/58) | 834 (727/107) (100/734) | 45 (16/29) |

Figures in parentheses refer to the numbers of SBS mutations found in homozygous or heterozygous state, respectively;

Figures in parentheses refer to the numbers of SBS mutations in exonic regions that were synonymous or nonsynonymous, respectively;

Indel figures in parentheses are deletion/insertion numbers followed by homozygous/heterozygous mutation numbers;

Frame/nonframe-shift figures in parentheses refer to the numbers of exonic mutations that were of frame-shift or nonframe-shift, respectively

Although the Chl-deficiency mutation rates increased and the seed-set rates decreased with increasing irradiation dose (Fig. 1a), the numbers of SBS mutations per P2M2 plant remained largely similar at 165 and 246 Gy, but were reduced at 389 Gy. Furthermore, the mutation rates in plants without discernible mutated phenotype were all higher than those with sterile mutant phenotypes at the same dose (Fig. 1a; Table 2).

More heterozygous mutations than homozygous ones of both SBS and Indel were observed in the six P2M2 plants (Table 2). Both SBS and Indel mutations scattered across the 12 chromosomes (Table S5), without apparent hotspots (Fig. 1b). They were located in coding, regulatory, or inter-genic regions (Fig. 1c).

All six possible types of substitutions were observed, with the transitions (Ti: C:G>T:A and T:A>C:G) to transversions (Tv: C:G>A:T, C:G>G:C, T:A>G:C, and T:A>A:T) ratios ranging from 1.15 to 1.68 (Fig. 1d). Among Indels, single base deletions and insertions were the most frequent, and short Indels (<4 bp) were more prevalent than long ones (Fig. 1d).

The mutations detected by NGS could include false positives, particularly in repetitive regions; therefore, a random selection of SBS and Indel mutations was subjected to validation by Sanger sequencing. Consequently, an estimated 25% SBSs and 20% Indels are false positives in non-repeated sequences and 55% Indels are false positives in repeated sequences (Tables S1 and S2). Furthermore, to verify whether the detected SBSs and Indels could be inherited, we designed markers for two SBSs and five Indels to genotype P3M3 plants and confirmed that the mutations were all passed to the P3M3 plants (Tables S1 andS2).

3.3. Structural and copy number mutations

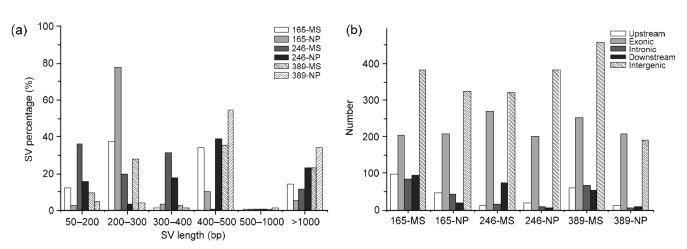

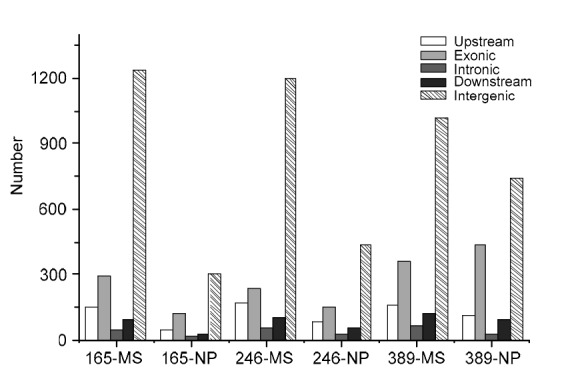

SVs were previously detected in γ ray-mutagenized plants through cytogenetic studies. Using NGS and bioinformatics analysis, we detected 428–906 SVs and 521–1832 CNVs in the six plants (Figs. 2 and 3). However, only about 10% of SVs and about 29% of CNVs were subsequently confirmed by PCR analysis (Tables S3 and S4).

Fig. 2.

Structural variation (SV) mutations induced by γ rays in six P2M2 rice plants

(a) Percentages of SV mutations with different sizes; (b) Frequencies of SV mutations in different genomic regions

Fig. 3.

Frequencies of copy number variation (CNV) mutations in different genomic regions in the six γ ray-mutagenized P2M2 rice plants

3.4. Estimate of mutation frequency

Based on the validation rates, the actual numbers of SBS and Indel mutations would be 1762 to 2936 and 426 to 486, respectively, in the six γ ray-mutagenized P2M2 plants (Table 3). With a rice reference genome size of 373 Mb, the mutational rates would be 4.7×10−6–7.9×10−6 for SBSs and 1.1×10−6–1.3×10−6 for Indels (Table 3).

Table 3.

Estimation of actual numbers and rates of single base substitution (SBS), insertion/deletion (Indel), structural variation (SV), and copy number variation (CNV) mutations in the six P2M2 plants based on the number of mutations identified by next-generation sequencing (NGS) and bioinformatics analysis, and the validation rates

| P2M2 plant | SBS |

Indel |

SV |

CNV |

Total |

||||||

| No. | Rate (×10−6) | No. in non-repetitive sequence | No. in repetitive sequence | Rate (×10−6) | No. | Rate (×10−6) | No. | Rate (×10−6) | No. | Rate (×10−6) | |

| 165-MS | 2443 | 6.64 | 202 | 225 | 1.14 | 87 | 0.23 | 523 | 1.40 | 3480 | 9.32 |

| 165-NP | 2936 | 7.92 | 238 | 218 | 1.22 | 64 | 0.17 | 149 | 0.40 | 3606 | 9.66 |

| 246-MS | 2578 | 7.00 | 203 | 233 | 1.17 | 69 | 0.19 | 505 | 1.35 | 3588 | 9.61 |

| 246-NP | 2924 | 7.83 | 216 | 235 | 1.21 | 62 | 0.17 | 218 | 0.58 | 3654 | 9.79 |

| 389-MS | 1762 | 4.72 | 242 | 217 | 1.23 | 89 | 0.24 | 497 | 1.33 | 2807 | 7.52 |

| 389-NP | 1869 | 5.05 | 253 | 233 | 1.30 | 43 | 0.11 | 408 | 1.09 | 2806 | 7.52 |

4. Discussion

Mutation breeding is based on induction of genetic variations by various mutagens; hence knowledge of the frequency and type of mutations induced is pivotal for the efficient design and implementation of mutation breeding programs. Previous studies on genetic effects of mutagenic treatment are either based on phenotypic data or focused on selected genes or genomic regions (Morita et al., 2009; Yoshihara et al., 2013; Nawaz and Shu, 2014); hence the knowledge generated has been limited in quantity and is incomplete in nature. The present study reveals the mutagenic effect of γ rays in plants at a single-nucleotide resolution.

4.1. Origin of mutations

Although the rice cultivar Nipponbare used in the present study (progenitor Nipponbare, Nip-P) is the same as the reference genome (Nip-R), the genome of the starting plant of Nip-P must have already been different from that of Nip-R because of spontaneous mutations over generations since their divergence. Therefore, the genetic variations identified in the P2M2 plants might have resulted from three sources: (1) the genome differences between Nip-P (P0) and Nip-R; (2) spontaneous mutations from P0 to P1 and from P1M1 to P2M2; and (3) γ ray-induced mutations (from P1 to P1M1) inherited to P2M2.

The difference between Nip-P (P0) and Nip-R could be homozygous or heterozygous at a particular locus; if it was homozygous, all M2 plants would be different from Nip-R at the site, in the form of common mutations among the six P2M2 plants; if it was heterozygous, it would be segregating in the P2M2 populations, but there was a good probability that at least two M2 plants had the same mutation. For spontaneous mutations generated from P0 to P1, the situation would be similar to the heterozygous alleles between Nip-P and Nip-R, whereas spontaneous mutations originating from P1M1 to P2M2 would be unique and different between any P2M2 plants. By contrast, all γ ray-induced mutations should be unique to individual seeds and different between any two P2M2 plants from different panicle rows, because the probability of generating a common mutation, either spontaneously or artificially induced (e.g. by γ rays), in two different individuals is extremely low, considering the random nature and extremely low frequency of such event.

Based on the above analysis, we reasoned that all genetic variations that are common in any two of the six plants either were caused by the difference between Nip-R and Nip-P or resulted from spontaneous mutation from P0 to P1. Hence they were excluded from mutation frequency analysis. Among the mutations unique to each P2M2 plant, γ ray-induced mutations should be the absolute majority, because all known spontaneous mutation rates in the plant are several orders of magnitude lower than the rate of 7.5×10−6 per generation per site, the lowest rate revealed among the six P2M2 plants. The reported spontaneous mutation rates are about 1×10−9 per generation per site in Arabidopsis (Ossowski et al., 2010), from 3.23×10−10 (Ness et al., 2012) to 11.5× 10−10 (Ness et al., 2015) in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, and from (1.67±0.04)×10−10 (Zhu et al., 2014) to 2.00×10−10 mutations per base per generation (Farlow et al., 2015) in yeast. The differences of spontaneous mutation rates between rice and Arabidopsis should not be greater than those between Arabidopsis and Chlamydomonas reinhardtii or between Arabidopsis and yeast, because phylogenetic Arabidopsis is more conserved with rice than with Chlamydomonas reinhardtii or yeast. Therefore the spontaneous mutation rate in rice should be similar to or slightly higher than (due to longer growth duration) that in Arabidopsis, e.g. about 5×10−9 per generation per site.

4.2. Type of γ irradiation-induced mutations

Previous studies on mutant genes showed that γ ray-induced mutations consisted mainly of deletions (Morita et al., 2009; Nawaz and Shu, 2014) or of both deletions and SBSs in M1 seedlings (up to 48.4% of total mutations (Yoshihara et al., 2013)). However, we observed that SBSs were much more abundant than Indels in the present study (Table S2). Our observation is similar to the fast-neutron-induced mutations revealed by NGS, where more SBSs were detected than Indels (Belfield et al., 2012). γ rays are known to damage DNA in two ways, i.e. direct deposit of ionizing energy resulting in DNA double strand breaks (DSBs), and indirect action of reactive oxygen species (e.g. H2O2, ⦁OH,O2 ⦁ −,) generated by ionization-induced water radiolysis (Lee et al., 2009; Lagoda, 2012), which could result in damage at the nucleotide level. Hence it is not unexpected to detect SBS mutations in the P2M2 plants. However, the predominance of SBS mutations over Indels does not necessarily reflect that more single nucleotide damages were produced than DSBs, because a large proportion of Indel mutations could be lethal or could not be passed down into their progeny due to somatic and haplontic competition (Prina et al., 2012).

Henry et al. (2015) failed to detect SBS mutations in the five poplar plants with relatively high sequencing depth (<14.5×). They attributed the non-finding of SBS mutation, which was different from previous reports on this subject, to the differences of materials used. Our analysis of their data also suggested that the non-finding is highly likely to be false negative due to the tremendous amount of heterozygous loci present in every poplar plant, which is estimated to be several orders of magnitude more than the number of mutations induced by γ irradiation. As direct evidence, they reported a 7% Indel mutation frequency in non-irradiated control plants (see Table 1 of Henry et al. (2015)); seemingly such Indels are more likely to be from heterozygous sites rather than mutations generated spontaneously in a single generation.

We observed all six possible types of substitutions; the Ti/Tv ratios (1.15 to 1.68; Fig. 1d) appear to be in the middle between those reported for spontaneous mutations (2.41–2.73 (Ossowski et al., 2010)) and fast-neutron-induced mutations (0.86 (Belfield et al., 2012)) in Arabidopsis plants. The Ti/Tv ratios are slightly lower than those reported for ethylmethane sulfonate (EMS) mutagenesis (1.63–1.83 (Mohd-Yusoff et al., 2015)) and greater than those in regenerated plants of rice (1.1 (Miyao et al., 2012)) and Arabidopsis (0.92 (Jiang et al., 2011)). These differences must be related to the nature of mutagens, but the underlying mechanism awaits further study.

False-positive variants are usually associated with sequencing and alignment errors (Dohm et al., 2008; Nakamura et al., 2011). We have taken several measures to reduce such errors, e.g. a target depth of >15 and a target minimum mapping quality of 20 (for details see Section 2.2). Furthermore, to examine the percentage of mutations truly induced by γ rays, we verified the mutation by Sanger sequencing. The false-positive detection rates of SBSs and Indels are similar to those in previous studies (Park et al., 2014).

4.3. Mutation frequency

Based on the number of mutations revealed by whole genome sequencing of rice plants and the subsequent validation rates of selected mutations, we estimated that γ irradiation of dry seeds resulted in heritable mutations at frequencies of 7.5×10−6 to 9.8×10−6 per generation per site (base pair) (Table 3), with a limited dose effect within the range of doses applied. In fast-neutron-mutagenized Arabidopsis plants, Belfield et al. (2012) estimated the mutation rates for SBS and Indel mutations at 2.6×10−7 and 0.9×10−7, respectively, which are about 10 times less than we observed for γ irradiation in rice. However, the mutation frequencies observed in the present study are similar to those reported in regenerated (5.9×10−7 to 3.3×10−6 SBSs per regeneration (Miyao et al., 2012)) and in EMS-induced rice plants (4.8×10−6 to 5.0×10−6 SBSs (Henry et al., 2014)), and in EMS-mutagenized Lotus japonicus ((6.8±4.9)×10−6 per generation per site (Mohd-Yusoff et al., 2015)).

The underlying mechanism leading to higher mutation rates in plants without discernible mutated phenotypes than those with sterile mutant phenotypes at the same dose (Fig. 1a; Table 2) has yet to be uncovered. It might have resulted from the non-transmission of a greater proportion of deleterious mutations from P1M1 to P2M2 plants, as was reported in the pollen mutagenesis study in Arabidopsis (Naito et al., 2005).

In summary, the present study represents the first whole-genome single nucleotide resolution examination of the inheritable mutations induced by γ rays in a seed-propagated plant. The findings of the present study are of direct importance for the proper and efficient use of γ rays in plant breeding and genetic studies. The similar mutation rates of plants irradiated with different doses of γ rays suggest that a lower dose than that commonly used could be applied. The existence of thousands of induced mutations in each P2M2 plant suggested that selected mutants should be subjected to further breeding by backcrossing to clear the deleterious mutations, and single seed selection, instead of bulk selection, should be applied in mutant line development because background mutations may still be segregating in M3 and advanced generations.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mr. Bin ZHANG (Zhejiang Zhijiang Seed Co., Hangzhou, China) for helping grow and manage the rice materials.

List of electronic supplementary materials

Verification of single base substitution (SBS) mutations in P2M2 and P3M3 plants

Verification of insertion and deletion (Indel) mutations in the P2M2 and P3M3 plants

Verification of structural variation (SV) mutations in P2M2 plants

Verification of copy number variation (CNV) mutations in P2M2 plants

Frequency of single base substitution (SBS) and Indel mutations in individual chromosomes of the six γ rays-mutagenized P2M2 plants (mutation numbers per million base pairs)

Genotyping of the selected six P2M2 plants and Nipponbare with 12 representative SSR markers

N stands for Nipponbare; Lanes 1–6 represent 165-MS, 165-NP, 246-MS, 246-NP, 389-MS and 389-NP plants, respectively

Footnotes

Project supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 11275171), the National Key Technology R & D Program of China (No. 2014BAA03B04), and the Mutation Breeding Project of the Forum for Nuclear Cooperation in Asia (FNCA)

Electronic supplementary materials: The online version of this article (http://dx.doi.org/10.1631/jzus.B1600125) contains supplementary materials, which are available to authorized users

Compliance with ethics guidelines: Shan LI, Yun-chao ZHENG, Hai-rui CUI, Hao-wei FU, Qing-yao SHU, and Jian-zhong HUANG declare that they have no conflict of interest.

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

References

- 1.Abyzov A, Urban AE, Snyder M, et al. CNVnator: an approach to discover, genotype, and characterize typical and atypical CNVs from family and population genome sequencing. Genome Res. 2011;21(6):974–984. doi: 10.1101/gr.114876.110. (Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/gr.114876.110) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahloowalia BS, Maluszynski M, Nichterlein K. Global impact of mutation-derived varieties. Euphytica. 2004;135(2):187–204. (Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/b:euph.0000014914.85465.4f) [Google Scholar]

- 3.Belfield EJ, Gan X, Mithani A, et al. Genome-wide analysis of mutations in mutant lineages selected following fast-neutron irradiation mutagenesis of Arabidopsis thaliana . Genome Res. 2012;22(7):1306–1315. doi: 10.1101/gr.131474.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen K, Wallis JW, McLellan MD, et al. BreakDancer: an algorithm for high-resolution mapping of genomic structural variation. Nat Methods. 2009;6(9):677–681. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1363. (Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.1363) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dohm JC, Lottaz C, Borodina T, et al. Substantial biases in ultra-short read data sets from high-throughput DNA sequencing. Nucl Acids Res. 2008;36(16):e105. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn425. (Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkn425) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Endo M, Kumagai M, Motoyama R, et al. Whole-genome analysis of herbicide-tolerant mutant rice generated by Agrobacterium-mediated gene targeting. Plant Cell Physiol. 2015;56(1):116–125. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcu153. (Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/pcp/pcu153) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Farlow A, Long H, Arnoux S, et al. The spontaneous mutation rate in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe . Genetics. 2015;201(2):737–744. doi: 10.1534/genetics.115.177329. (Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1534/genetics.115.177329) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Henry IM, Nagalakshmi U, Lieberman MC, et al. Efficient genome-wide detection and cataloging of EMS-induced mutations using exome capture and next-generation sequencing. Plant Cell. 2014;26(4):1382–1397. doi: 10.1105/tpc.113.121590. (Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1105/tpc.113.121590) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Henry IM, Zinkgraf MS, Groover AT, et al. A system for dosage-based functional genomics in poplar. Plant Cell. 2015;27(9):2370–2383. doi: 10.1105/tpc.15.00349. (Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1105/tpc.15.00349) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hofinger BJ, Jing HC, Hammond-Kosack KE, et al. High-resolution melting analysis of cDNA-derived PCR amplicons for rapid and cost-effective identification of novel alleles in barley. Theor Appl Genet. 2009;119(5):851–865. doi: 10.1007/s00122-009-1094-2. (Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00122-009-1094-2) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jiang C, Mithani A, Gan X, et al. Regenerant Arabidopsis lineages display a distinct genome-wide spectrum of mutations conferring variant phenotypes. Curr Biol. 2011;21(16):1385–1390. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.07.002. (Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2011.07.002) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kawakatsu T, Kawahara Y, Itoh T, et al. A whole-genome analysis of a transgenic rice seed-based edible vaccine against cedar pollen allergy. DNA Res. 2013;20(6):623–631. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dst036. (Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/dnares/dst036) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lagoda PJL. Effects of radiation on living cells and plants. In: Shu QY, Forster BP, Nakagawa H, editors. Plant Mutation Breeding and Biotechnology. Wallingford: CABI Publishing; 2012. pp. 123–134(comment). (Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1079/9781780640853.0123) [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee MH, Moon YR, Chung BY, et al. Practical use of chemical probes for reactive oxygen species produced in biological systems by γ-irradiation. Radiat Phys Chem. 2009;78(5):323–327 https://dxdoiorg/101016/jradphyschem200903001. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, et al. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(16):2078–2079. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352. (Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lu HP, Edwards M, Wang QZ, et al. Expression of cytochrome P450 CYP81A6 in rice: tissue specificity, protein subcellular localization, and response to herbicide application. J Zhejiang Univ-Sci B (Biomed & Biotechnol) 2015;16(2):113–122. doi: 10.1631/jzus.B1400168. (Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1631/jzus.B1400168) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miyao A, Nakagome M, Ohnuma T, et al. Molecular spectrum of somaclonal variation in regenerated rice revealed by whole-genome sequencing. Plant Cell Physiol. 2012;53(1):256–264. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcr172. (Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/pcp/pcr172) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mohd-Yusoff NF, Ruperao P, Tomoyoshi NE, et al. Scanning the effects of ethyl methanesulfonate on the whole genome of Lotus japonicus using second-generation sequencing analysis. G3. 2015;5(4):559–567. doi: 10.1534/g3.114.014571. (Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1534/g3.114.014571) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morita R, Kusaba M, Iida S, et al. Molecular characterization of mutations induced by gamma irradiation in rice. Genes Genet Syst. 2009;84(5):361–370. doi: 10.1266/ggs.84.361. (Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1266/ggs.84.361) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Naito K, Kusaba M, Shikazono N, et al. Transmissible and nontransmissible mutations induced by irradiating Arabidopsis thaliana pollen with γ-rays and carbon ions. Genetics. 2005;169(2):881–889. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.033654. (Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1534/genetics.104.033654) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nakamura K, Oshima T, Morimoto T, et al. Sequence-specific error profile of Illumina sequencers. Nucl Acids Res. 2011;39(13):e90. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr344. (Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkr344) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nawaz Z, Shu QY. Molecular nature of chemically and physically induced mutants in plants: a review. Plant Genetic Res. 2014;12(S1):S74–S78. (Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/s1479262114000318) [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ness RW, Morgan AD, Colegrave N, et al. Estimate of the spontaneous mutation rate in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii . Genetics. 2012;192(4):1447–1454. doi: 10.1534/genetics.112.145078. (Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1534/genetics.112.145078) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ness RW, Morgan AD, Vasanthakrishnan RB, et al. Extensive de novo mutation rate variation between individuals and across the genome of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii . Genome Res. 2015;25(11):1739–1749. doi: 10.1101/gr.191494.115. (Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/gr.191494.115) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ossowski S, Schneeberger K, Lucas-Lledó JI, et al. The rate and molecular spectrum of spontaneous mutations in Arabidopsis thaliana . Science. 2010;327(5961):92–94. doi: 10.1126/science.1180677. (Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.1180677) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Park MH, Rhee H, Park JH, et al. Comprehensive analysis to improve the validation rate for single nucleotide variants detected by next-generation sequencing. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(1):e86664. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0086664. (Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0086664) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peng ST, Zhuang JY, Yan QC, et al. SSR markers selection and purity detection of major hybrid rice combinations and their parents in China. Chin J Rice Sci. 2003;17(1):1–5. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pettersson C, Hettinger G. Dosimetry of high-energy electron radiation based on the ferrous sulphate dosimeter. Acta Radiol Ther Phys Biol. 1967;6(2):160–176. doi: 10.3109/02841856709138575. (Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/02841856709138575) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Prina AR, Landau AM, Pacheco MG. Chimeras and mutant gene transmission. In: Shu QY, Forster BP, Nakagawa H, editors. Plant Mutation Breeding and Biotechnology. Wallingford: CABI Publishing; 2012. pp. 181–189. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tan YY, Fu HW, Zhao HJ, et al. Functional molecular markers and high-resolution melting curve analysis of low phytic acid mutations for marker-assisted selection in rice. Mol Breeding. 2013;31(3):517–528. (Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11032-012-9809-5) [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang K, Li MY, Hakonarson H. ANNOVAR: functional annotation of genetic variants from high-throughput sequencing data. Nucl Acids Res. 2010;38(16):e164. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq603. (Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkq603) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yoshihara R, Nozawa S, Hase Y, et al. Mutational effects of γ-rays and carbon ion beams on Arabidopsis seedlings. J Radiat Res. 2013;54(6):1050–1056. doi: 10.1093/jrr/rrt074. (Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/jrr/rrt074) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zheng XG, Chen L, Lou QJ, et al. Changes in DNA methylation pattern at two seedling stages in water saving and drought-resistant rice variety after drought stress domestication. Rice Sci. 2014;21(5):262–270. (Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/s1672-6308(13)60194-8) [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhu YO, Siegal ML, Hall DW, et al. Precise estimates of mutation rate and spectrum in yeast. PNAS. 2014;111(22):e2310–e2318. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1323011111. (Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1323011111) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Verification of single base substitution (SBS) mutations in P2M2 and P3M3 plants

Verification of insertion and deletion (Indel) mutations in the P2M2 and P3M3 plants

Verification of structural variation (SV) mutations in P2M2 plants

Verification of copy number variation (CNV) mutations in P2M2 plants

Frequency of single base substitution (SBS) and Indel mutations in individual chromosomes of the six γ rays-mutagenized P2M2 plants (mutation numbers per million base pairs)

Genotyping of the selected six P2M2 plants and Nipponbare with 12 representative SSR markers

N stands for Nipponbare; Lanes 1–6 represent 165-MS, 165-NP, 246-MS, 246-NP, 389-MS and 389-NP plants, respectively