Abstract

Background/Objectives

Pain is universal, undertreated, and impedes recovery in hip fracture. This study compared outcomes for regional nerve blocks to standard analgesics following hip fracture.

Design

Multi-site randomized controlled trial from 4/2009-3/2013.

Setting

3 New York hospitals.

Participants

161 hip fracture patients.

Intervention

79 patients were randomized to receive an ultrasound-guided single injection femoral nerve block administered by emergency physicians at emergency department admission followed by placement of a continuous fascia iliaca block by anesthesiologists within 24 hours. 82 control patients received conventional analgesics.

Measurements

Pain (0-10 scale), distance walked on post-operative day (POD) 3, Walking ability at 6 weeks following discharge, opioid side effects.

Results

Pain scores 2 hours following emergency department presentation favored the intervention group compared to controls (3.5 versus 5.3 respectively, P=.002). Pain scores on POD 3 were significantly better for the intervention as compared to the control group for pain at rest (2.9 versus 3.8, p=.005), with transfers out of bed (4.7 versus 5.9, p=.005), and with walking (4.1 versus 4.8, p=.002). Intervention patients walked significantly further than controls in 2 minutes on POD 3 (170.6 feet (95% CI 109.3, 232) versus 100.0 feet (95% CI 65.1, 134.9) respectively. P=.041). At 6 weeks, intervention patients reported better walking and stair climbing ability (mean FIM locomotion scores of 10.3 (95% CI 9.6, 11.0) versus 9.1 (95% CI 8.2, 10.0), P=0.045. Intervention patients reported significantly fewer opioid side effects (3% versus 12.4%, P=.028) and required 33-40% fewer parenteral morphine sulfate equivalents.

Conclusion

Femoral nerve blocks performed by emergency physicians followed by continuous fascia iliaca blocks placed by anesthesiologists are feasible and result in superior outcomes.

Keywords: pain, hip fracture, functional recovery

INTRODUCTION

Over 250,000 adults over age 65 are hospitalized with hip fracture in the U.S. annually and this number is expected to increase to 289,000 by 2030.1,2 For the 80% of patients who survive to six months post fracture, 60% will have recovered their pre-fracture walking ability and only 50% will have recovered their pre-fracture ability to perform their activities of daily living.3 Despite its perception as a surgical problem, almost all hip fracture patients are treated by geriatricians/internists/family physicians, emergency physicians, anesthesiologists, physiatrists and surgeons.4 In a single care episode, they receive treatment in emergency departments (EDs), operating rooms, surgical and medicine services, and have rehabilitation services in acute and sub-acute centers, nursing homes, or their own homes following discharge.4

Given the impact of hip fracture on function - after one year, only 54% of surviving patients are able to walk unaided3 – interventions to improve post-operative recovery are needed. Pain is universally present and a major impediment to recovery in hip fracture.5 Observational studies have shown that hip fracture pain has been associated with an increased risk of post-operative complications5-7 and has been shown to lead to prolonged bed rest, delayed ambulation, missed or shortened physical therapy sessions, and impaired function post-operatively and as long as six months following surgery.5 Whereas opioids are an effective treatment for pain, opioids are problematic in older adults due to their side effect profile.8,9

Due to their potential to reduce opioid side effects, regional anesthetic techniques are attractive alternatives in older adults with fracture pain. Two recent systematic reviews have highlighted the benefits of perioperative nerve blocks compared to standard care (oral and parenteral analgesics) in reducing hip fracture pain, and the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons recently issued a strong recommendation to employ these techniques in the management of this disease.10,11 Nevertheless, the integration of these techniques into routine care has been problematic. A comprehensive review on the management of pain in hip fracture noted that although “nerve blockade is within the repertoire of most practicing anesthesiologists, many clinicians do not perform it routinely because they believe the additional time, effort, and supervision required may outweigh the benefits.”11 It is also unclear as to the effect of blockades on ambulation or rehabilitation, outcomes beyond the peri-operative period, and systemic opioid use.

Ideally, effective pain management for hip fracture should begin at presentation to the ED and be seamlessly integrated into routine medical and surgical care. We have previously reported results which demonstrated that femoral nerve blocks administered under ultrasound guidance can be taught to and administered safely by emergency physicians (EP)12 and that a mobile peripheral nerve block service can be seamlessly integrated into routine pre-operative hip fracture care.13 Here, we report the main outcomes of our randomized controlled trial that compared a pain management program comprised of a single injection femoral nerve block (FNB) administered by EPs followed by placement of a continuous fascia iliaca block (cFIB) by anesthesiologists 24 hours later to conventional analgesic treatment (opioids and acetaminophen administered at treating physician discretion) at 3 New York hospitals. Outcomes included ED pain, pain and function post-operatively and 6 weeks following discharge, as well as opioid requirements and side effect incidence.

METHODS

Study Design

We conducted a randomized controlled trial to compare peripheral nerve blocks versus conventional analgesic therapy in hip fracture patients aged 60 years and older presenting to 3 New York EDs on outcomes of pain, functional recovery, and analgesic side effects. The study hospitals included a 1,171 bed quaternary care academic medical center (Mount Sinai) and an 856 bed academic teaching hospital (Beth Israel), both located in Manhattan, and a 711 bed teaching hospital in Brooklyn (Maimonides Medical Center). Maimonides was added as a third site mid-way through the study (10/11) due to declining hip fracture admissions at Beth Israel. Following training sessions for EPs at the 3 study sites in the utility and performance of FNBs (described elsewhere12), eligible and consenting hip fracture patients presenting to study hospitals were randomized to receive FNB (intervention) or standard therapy (control) in the ED. Intervention patients subsequently had a cFIB placed by an anesthesiologist within 24 hours after the initial single injection FNB, either on the orthopedic ward or in the operating room at the time of surgery – whichever occurred sooner. This mobile peripheral nerve block service has been previously described.13 Control patients received conventional standing and “as needed” parenteral or oral analgesics (opioids and acetaminophen) as determined by the treating physicians. Evidence and expert guidance available at the time of the study did not yet support the use of nerve blocks over conventional analgesics and standard practice in the study institutions did not include regional nerve blocks for hip fracture analgesia.

Subjects were interviewed daily about pain and opioid related side effects, had physical performance testing conducted on post-operative day (POD) 3, and were interviewed by telephone 6 weeks after discharge to assess walking ability. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the 3 participating hospitals.

Patients

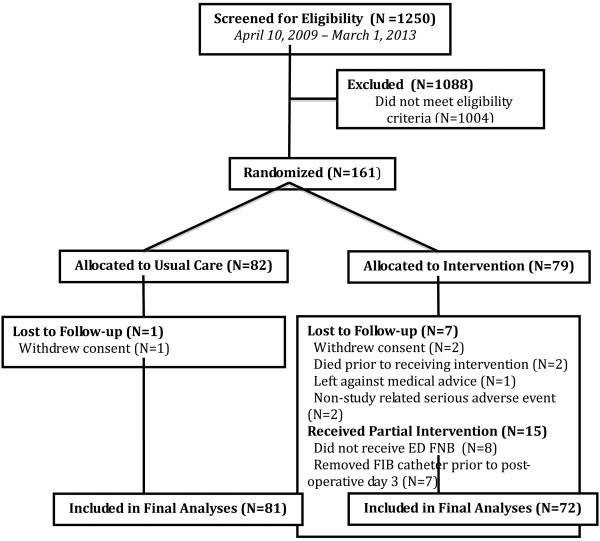

All admissions to the 3 EDs were prospectively screened daily from 08:00 to 20:00, Sundays to Fridays, 4/2009 through 3/2013 by trained clinical interviewers. The screening window was based on admission data that suggested that 80% of hip fracture patients would be captured during this time period. Patients were eligible for inclusion if they were aged 60 years or older with a radiographically confirmed hip fracture (femoral neck, intertrochanteric, or peri-capsular). Exclusion criteria are detailed in Figure 1. All patients gave written consent.

Figure 1. CONSORT Diagram.

Figure 1 details enrollment statistics and intervention protocols. Patients were eligible for inclusion if they were aged 60 years or older with a radiographically confirmed hip fracture (femoral neck, intertrochanteric, or peri-capsular). We excluded patients: with multiple trauma, cancer-related fractures, bilateral hip fractures, or previous fracture or surgery at the currently fractured site; transferred from another hospital; presenting greater than 48 hours after fracture; with a history of substance abuse as evidenced by an affirmative response to either of the first two items on the Drug Abuse Screening Test14 or documentation of a history of substance abuse in the medical record; who were delirious as determined by the Confusion Assessment Method (CAM);15 who did not speak English, Spanish, or Russian; with a history of an allergy or adverse reaction to bupivacaine/ropivicaine; with an allergy to opioid analgesics; with a bleeding diatheses, unable to self-report their pain, or with moderate cognitive impairment as documented by a score of 3 or less on the Callahan six item screener.16 Details regarding the 1004 excluded patients are as follows: Advanced dementia - 390, ruled out for hip fracture - 86, presented after study hours - 102, under age 60 - 168, language barrier - 72, pathologic fracture - 68, over 48 hours at home before presenting to ED - 45, decision for non-operative management - 29, bilateral fracture - 17, substance abuse - 15, transferred from another hospital - 12. Following enrollment, subjects were randomized to FNB or conventional care using a stratified blocked randomization list with stratification by site. The block size for the randomization was randomly chosen for each block as either 2, 4 or 6 patients.33.

Randomization and Masking

Subjects were randomized to FNB or standard care (control) using a computer generated stratified blocked randomization list with stratification by site. The block size for the randomization was randomly chosen for each block as two, four or six patients. After determining eligibility and obtaining informed consent at ED admission, the interviewers (CIs) conducted an initial brief pain interview. After conducting the initial interview, CIs informed the treating physician that the patient was enrolled in the trial, left the ED and contacted the project manager to inform her of a study enrollment in the ED and the identity of the treating physician. The project manager determined randomization status by opening a sealed envelope, and while remaining blinded to the patient’s identity, contacted the treating EP to let them know if their enrolled patient was to receive a FNB or standard analgesic care. Intervention patients were also able to receive as needed opioids at the discretion of treating physicians. CIs remained blinded to patients’ randomization status throughout the trial, as did the investigators.

Procedures

In July of each study year (October of 2011 at Maimonides initially), all incoming EP residents at each site were trained in ultrasound-guided FNB.12 Additionally, a core group of teaching attending EPs were trained at each site to ensure appropriate oversight. The single shot FNB consisted of 20 mL of 0.5% bupivacaine and was performed under ultrasound guidance. Within twenty-four hours after the FNB or at the time of surgery, whichever was sooner, an anesthesiologist inserted a cFIB infusion catheter under ultrasound guidance. A bolus of 15 mL of 0.2% ropivacaine was injected followed by a continuous infusion of 0.2% ropivacaine at 5 mL/hour. Catheters were removed after POD 3.

Control patients received oral and intravenous analgesic therapy at the discretion of the treating physician. Sham saline injections and catheter infusions were considered but rejected as pilot data demonstrated that both EPs and anesthesiologists would not perform sham injections as they believed them to be “unethical”. Sham catheters taped to the skin were initially employed as a blinding technique for the cFIB but were subsequently discarded early in the course of the study as they failed to blind clinical nursing staff.

Immediately after obtaining informed consent at ED admission, CIs queried eligible patients about their pain. Enrolled patients were asked to rate their pain on a 0-10 numeric rating scale (NRS) with 0 being no pain and 10 the worst pain imaginable. Subjects were also queried as to their current pain level (0-10 NRS) and pain relief (worse pain than prior pain, no relief, slight relief, moderate relief, a lot of relief, complete relief) 1 and 2 hours following enrollment.

Patients were interviewed by CI’s on a daily basis (Sunday-Friday). Patients were asked to rate their pain at rest, with transfer out of bed, and with walking past a bedside chair on 0-10 NRSs. CIs performed daily assessments of opioid side effects14 and delirium using the Confusion Assessment Method supplemented by chart review.7 If a patient was not able to be interviewed on a particular day (e.g., Saturdays or because they were unavailable and off the floor), we asked these patients on the following day to rate their present pain level and their pain on the prior missed day. On POD 3, patients cleared for weight bearing performed a 2-minute walk under supervision of a physical therapist and the distance ambulated was recorded. Patient characteristics were obtained from interviews and medical record review. Comorbid conditions were measured using the Charlson comorbidity index.15 Functional status before fracture was measured using the motor subscales of the Functional Independence Measure (FIM),16 depression using the 15-item Geriatric Depression Scale,17 and overall health-related quality of life according to self-report using excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor. CIs interviewed patients by telephone 6-weeks after discharge about their functional status.

Outcomes

Main outcome measures included pain at 1 and 2 hours following ED admission, pain at rest, with transfers out of bed, and with walking on POD 3 and distance walked in 2 minutes on POD 3. Secondary outcomes included opioid requirements (morphine sulfate equivalents) and opioid related side-effects (1 or more days of severe nausea, sedation, or mental cloudiness), number of physical therapy sessions missed or shortened, and FIM locomotion scores (ability to walk and climb stairs) 6 weeks after discharge.

Statistical Analyses

Our initial sample size projections targeted a total sample size of 396 subjects to provide 80% power to detect a 0·5-point difference in ED and post-operative pain scores using a two-sided α of ·05 employing standard deviations and means from our prior publications. Midway through our planned patient enrollment it became apparent that the rate of hip fractures had declined substantially at one of our study hospitals and the study’s Data Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB) recommended adding two additional study sites pending the results of a pre-planned interim analysis. The interim analysis, however, revealed a markedly greater effect size of the intervention on pain scores and function than hypothesized. As a result of these analyses, the DSMB advised a reduction in the targeted sample size to 150 patients, and recommended adding only one additional site – Maimonides Medical Center. Differences between study groups in baseline characteristics and clinical outcomes were assessed with two-sided Fisher’s exact tests, chi-square tests for categorical variables, and independent-samples Student’s t-tests for continuous variables. All analyses were intention to treat and performed using STATA version 13.1.18 In order to reduce the possibility of an inflated Type 1 error due to multiple comparisons, p-values were adjusted (q) using the Benjamini–Hochberg False Discovery Rate (FDR) procedure (Q = 0.05). 19,20 Multivariable analyses (not presented) controlling for age, pre-fracture functional status, pre-fracture pain levels, type of fracture/repair, and pre-existing comorbidity revealed similar results.

This project was supported by a grant (R01AG030141) from the National Institute on Aging (NIA) and an NIA appointed DSMB oversaw the trial. The trial is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov, Identifier: NCT00749489.

RESULTS

Study enrollment details and patient characteristics are in Figure 1 (CONSORT diagram) and Table 1 respectively. Analyzable data were available for 81 control (98% of enrolled subjects) and 72 intervention patients (91% of enrolled subjects) at hospital discharge and 57 (70%) control and 51 (71%) intervention patients at 6 weeks following discharge. Eight intervention patients (11%) were transferred to the operating room before they could receive an ED FNB. Seven intervention patients (no overlap) had their cFIB catheter removed prior to POD 3 (2 at patient request, 3 became dislodged, and nursing staff insisted that 2 be removed because patients developed delirium that staff attributed to the catheters). There were no significant differences in baseline patient characteristics between the two groups and between patients who completed the study and those lost to follow-up.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of the Intention-To-Treat Population

| Control (N=81) |

Intervention (N=72) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Baseline characteristics | ||

| Mean age (in years) | 81.7 (60-97) | 83.4 (62-98) |

| Women (%) | 57 (70.4) | 54 (75) |

| Living at home (%) | 72 (89) | 66 (92) |

| Race White (%) Black (%) Other (%) |

75 (93) 2 (2) 4 (5) |

63 (88) 6 (8) 3 (4) |

| Hispanic (%) | 78 (96) | 66 (92) |

| Mean Charlson Co-Morbidity Score (range) | 1.5 (0-9) | 1.4 (0-8) |

| Mean Geriatric Depresssion Scale score (range) | 4.3 (0-14) | 4.5 (0-15) |

| Self rated health (range) | 3.0 (1-5) | 2.9 (1-5) |

| Mean FIM locomotion score at admission (range) | 12.0 (3-14) | 12.5 (4-14) |

| Insurance Medicare only (%) Medicaid only (%) Medicare/Medicaid only (%) Commercial Insurance (%) Uninsured |

66 (81) 2 (2) 3 (4) 9 (11) 1 (1) |

64 (89) 1 (1) 2 (3) 5 (7) 0 (0) |

| Study site Hospital A Hospital B Hospital C |

15 (19) 34 (42) 32 (40) |

13 (18) 30 (42) 29 (40) |

| Average pain in week prior to fracture (range) | 1.8 (0-10) | 2.0 (0-10) |

| Pain with walking in week prior to fracture (range) | 1.7 (0-10) | 1.9 (0-10) |

| Taking analgesics prior to fracture (%) | 27 (33) | 23 (32) |

| Perioperative characteristics | ||

| Mean time to surgery in days (range) | 1.4 (0-7) | 1.5 (0-4) |

| Fracture type/Surgical Repair Femoral neck fracture/hemiarthroplasty (%) Femoral neck fracture/internal fixation (%) Intertrochanteric fracture (%) |

20 (25) 9 (11) 51 64) |

25 (35) 8 (11) 38 (53) |

| Regional anesthesia (%) | 51 (63) | 44 (61) |

| Discharge characteristics | ||

| Discharge site Home Acute rehabilitation Sub-acute rehabilitation Nursing home Died |

9 (11) 59 (73) 9 (11) 2 (2) 2 (2) |

6 (8.3) 58 (81) 5 (7.0) 2 (3) 1 (1) |

| Mean Hospital length of stay in days (range) | 6.2 (2-32) | 6.4 (0-42) |

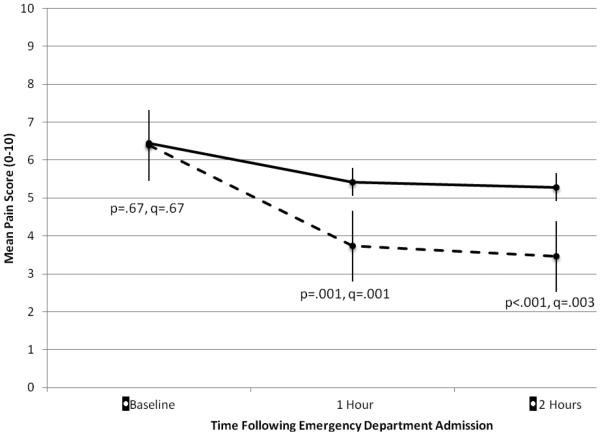

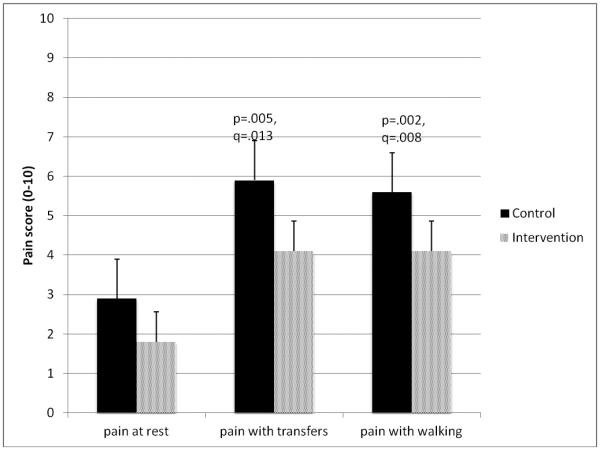

There were no significant differences in baseline pain at ED admission. Compared to controls, intervention patients had significantly less pain both at 1 hour (3.7 (95% CI 3.0, 4.5) versus 5.3 (95% CI 4.7, 6.1), p=.001, q=.001) and 2 hours following ED admission (3.5 (95% CI 2.8, 4.3) versus 5.3 (95% CI 4.6, 6.0), p<.001, q=.003 (Figure 2) Pain scores on POD 3 also favored the intervention (Figure 3). Compared to control patients, patients in the intervention arm had significantly less pain at rest (1.8 (95% CI .9,1.9) versus 2.9 (95% CI 2.3, 3.6), p=.005, q=.013), with transfers (4.7 (95% CI 4.1, 5.3) versus 5.9 (95% CI 5.2, 6.6), p=.005, q=.013), and with walking (4.1 (95% CI 3.5, 4.8) versus 5.6 (95% CI 4.8, 6.4), p=.002, q=.008)

Figure 2. Emergency Department Pain.

Mean pain scores with standard errors for pain at ED admission (baseline) and subsequently at 1 and 2 hours following ED admission for control patients (solid lines) and intervention patients (dashed lines). Pain was rated on numeric rating scales from 0-10.

Figure 3. Post-Operative Pain Outcomes.

Mean pain scores for pain at rest, pain with transfers out of bed, and pain with walking with standard error bars for control patients (shaded) and intervention patients (hashed) for post-operative days 3. Pain was rated on numeric rating scales from 0-10.

Function was improved in the intervention patients as compared to controls. Intervention patients walked over 70 feet farther in 2 minutes on POD 3 as compared to controls: 170.6 feet (95% CI 109.3, 232.0) compared to 100.0 feet (95% CI 65.1, 134.9), p=.041, q=.048. Compared to controls, intervention patients were significantly more likely to report that they were walking beyond a bedside chair by POD 3 (82% versus 64% respectively, odds ratio 2.49, 95% CI 1.17, 5.29, p=.018, q=.039), and were significantly less likely to have a physical therapy session missed or shortened (12.5% versus 27.2% of controls (odds ratio=.38, 95% CI .16, .89, p=.027, q=.048). At 6 weeks, intervention patients reported better walking and stair climbing ability (mean FIM locomotion scores of 10.3 (95% CI 9.6, 11.0) versus 9.1 (95% CI 8.2, 10.0) for controls, p=0.045, q=.049).

Intervention patients required 33% fewer parenteral morphine sulfate equivalents than controls in the ED (0.8 mg/hour (95% CI .64, 1.05) versus 1.2 mg/hour (95% CI 0.94, 1.40) respectively, p=.035, q=.048). Post-operatively for the first 3 days, control patients received an average of 3.5 mg/day (95% CI 2.46, 4.48) of parenteral morphine sulfate equivalents as compared to 2.1 mg/day (95% CI, 1.16, 2.95) for intervention patients (P=0.04, q=.048). The number of patients reporting a severe opioid-related side effect (one or more days of severe nausea, sedation, or unclear thinking) was significantly lower in the intervention group versus control (3.0% versus 12.4%, OR=0.20, 95% CI .04, .96, p=.044, q=.048). There were no episodes of bleeding, falls, or catheter related infections in the intervention group and delirium rates were similar in both groups (17.1% in the control and 15.9% in the intervention, p=0.83).

CONCLUSIONS

Our results suggest that an interdisciplinary, regional anesthesia-based nerve block program for acute hip fracture patients involving early single shot FNBs performed by EPs followed by cFIBs performed by anesthesiologists is feasible and provides superior analgesic and functional outcomes when compared to conventional oral and parenteral analgesic therapy. Patients randomized to the intervention reported lower pain scores following ED admission, and this improvement persisted through POD 3. Intervention patients were also observed to have enhanced walking ability post-operatively and at 6 weeks after hospital discharge and had lower opioid requirements.

Whereas untreated pain has been shown to be associated with increased suffering and other adverse outcomes in hip fracture,7,21 its treatment remains problematic.11,22 Scheduled opioid therapy, although shown to be effective in improving pain and other outcomes,14 is difficult to manage and associated with challenging side effects in older adults. Peripheral nerve blocks performed by anesthesiologists have been shown to result in improved pain management as compared to standard analgesic therapy (acetaminophen/opioids).11 Despite recent guidelines recommending their use,10 regional nerve blocks have yet to become the standard of care in the management of hip fracture pain – largely because of logistical difficulties in getting anesthesiologists to the ED and because of beliefs that the additional time and effort outweigh the block’s benefits.

This study adds to the existing literature described above in several important ways and presents novel findings. First, it replicates the results of prior single site and single operator studies that have demonstrated enhanced analgesia associated with regional nerve blocks as compared to oral and parenteral analgesic therapies.10,11 As importantly, this is the first multicenter trial to our knowledge that demonstrates that regional nerve blocks can result in improved ambulation following hip fracture as compared to traditional analgesic treatments.10 Indeed the difference in the FIM locomotion scale represents the difference of being able to walk 150 feet as compared to less than 50 feet without human assistance. In real-life terms, this may represent the difference between being confined at home versus having the ability to ambulate for reasonable distances outside the home.

Second, we have shown that our interdisciplinary analgesic program of a single FNB placed immediately upon fracture diagnosis in the ED followed by a cFIB results in significantly improved pain control, lower rates of opioid-related side effects, and lower opioid requirements as compared to conventional analgesic therapy within one hour of presentation through POD 3. Our study builds upon prior research by extending the period of analgesia compared to studies that have only employed single blocks (either in the ED or immediately prior to surgery)23-27 and by providing analgesia immediately after presentation to the ED as compared to studies that employed continuous blocks at the time of surgery.28 Third, we have extended the work of Fletcher et al23 by demonstrating that emergency physicians can be trained effectively in ultrasound-guided FNB12 and that this procedure can be performed safely and efficaciously in 3 diverse EDs thus ensuring immediate and effective relief for hip fracture-related pain. Finally, we have demonstrated that placement of cFIB can be easily integrated into pre-operative hip fracture care by anesthesiologists using a mobile block service.13 In both settings – the ED and perioperative medical/surgical floors, blocks are well tolerated by patients, and do not appear to interfere with surgical repair, post-operative recovery, physical therapy, post-operative ambulation, nor are they associated with increased rates of complications.

There are several limitations to this study. Patients did not receive sham nerve blocks and it is possible that some of our observed results may have resulted from a placebo effect. Sham blocks were considered but rejected due to ethical concerns of subjecting patients to unnecessary pain and because our EP clinical partners refused to administer sham injections. Our control group consisted of patients receiving “usual pain care” and consistent with studies,5,14,29 pain management practice at all study sites was not reflective of expert guideline recommendations in terms of opioid dosing, use of regularly scheduled analgesics, and management of opioid side effects. Whereas one could argue that the provision of guideline appropriate opioid therapy might mitigate the differences in outcomes observed in our trial, two decades of research and quality improvement programs have failed to ensure that patients in pain receive adequate opioid therapy.30 Although the cFIB were well tolerated, 10% of intervention patients either requested that the catheter be discontinued or had the catheter become dislodged and elected not to have it reinserted. Enrollment in our study was limited to a specific population of hip fracture patients and as such, our results may not generalize to the hip fracture population as a whole. For example, we only enrolled patients who were able to self-report their pain and we do not have data on patients with advanced dementia. Given known disparities in treatment of pain in dementia patients,31 they may benefit even more from these procedures than our study subjects. Other groups excluded included those on anticoagulants or platelet inhibitors and those who did not speak English, Spanish, or Russian. We were also not able to evaluate the maintenance of FNB skill among EPs over a period longer than 1 year. Nevertheless, ultrasound-guided procedures (vascular access, paracentesis, lumbar puncture, and other regional blocks) have become well integrated into EM practice, and are now considered fundamental components of emergency medicine.32 Finally, 29% of our sample could not be contacted at 6 weeks and it is possible that the improvements in function that we observed in the intervention group might not have persisted at this time frame had the full sample been available for analyses. Prior studies, albeit observational and non-randomized clinical trials, have shown similar improvements in post-discharge function associated with better pain management.5,14

In summary, this randomized controlled trial of regional nerve blocks and catheters to control hip fracture pain beginning at ED admission revealed important and novel findings. It is the largest and most rigorously designed study to date of the use of regional nerve blocks in this disease in older adults and provides the first randomized controlled trial data showing that reducing peri-operative pain improves functional outcomes. Our research, combined with prior smaller single site studies, supports the integration of regional nerve blocks into the routine care for hip fracture patients commencing with their presentation to the ED.

Acknowledgments

Funding Source: This project was supported by a grant (R01AG030141) from the National Institute on Aging. Dr. Morrison was supported by a Mid-Career Investigator Award in Patient Oriented Research (AGK24AG022345) and by Older Adult Independence Center Grant (5P30AG028741) from the National Institute on Aging. Dr. Hwang was supported by a Mentored Patient-Oriented Research Career Development Award (K23AG031218) from the National Institute on Aging.

Grant: This project was supported by a grant (R01AG030141) from the National Institute on Aging. Dr. Morrison was supported by a Mid-Career Investigator Award in Patient Oriented Research (AGK24AG022345) and by Older Adult Independence Center Grant (5P30AG028741) from the National Institute on Aging. Dr. Hwang was supported by a Mentored Patient-Oriented Research Career Development Award (K23AG031218) from the National Institute on Aging.

Footnotes

Trial registration: ClinicalTrials.gov, Identifier: NCT00749489. Available at: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00749489?term=hip+fracture&state1=NA%3AUS%3ANY&rank=1

Conflict of Interest: The editor in chief has reviewed the conflict of interest checklist provided by the authors and has determined that the authors have no financial or any other kind of personal conflicts with this paper. Dr. Silverstein died prior to the study’s completion. At the time of his death, he reported on conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions: R. Sean Morrison and Knox H. Todd:– co-principle investigators 1) conceived the work, oversaw the performance of the study, performed and oversaw the analyses, interpreted the data; and drafted the article; 3) participated in revising it critically for important intellectual content and wrote the submitted manuscript draft; 3) gave final approval of the version submitted; and 4) agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Eitan Dickman assisted in 1) performance of the study, analysis of results, and interpretation of data; 2) participated in revising the draft critically for important intellectual content; 3) gave final approval of the version submitted; and 4) agrees to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Ula Hwang, Meg A. Rosenblatt assisted in 1) the conception of the work, assisted in the performance of the study, analysis of results, and interpretation of data; 2) participated in revising the draft critically for important intellectual content; 3) gave final approval of the version submitted; and 4) agrees to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Saadia Akhtar, Jennifer Huang, Christina L. Jeng, Bret P. Nelson, Reuben J. Strayer, Toni M. Torrillo, Taja Ferguson assisted in 1) performance of the study and interpretation of data; 2) participated in revising the draft critically for important intellectual content; 3) gave final approval of the version submitted; and 4) agrees to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Jeffrey H. Silverstein assisted in 1) conception of the work, assisted in performance of the study and interpretation of data; 2) participated in revising the draft critically for important intellectual content; 3) gave final approval of the version submitted; and 4) agrees to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Sponsor’s Role: The funder of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report. The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

REFERENCES

- 1.Stevens JA, Rudd RA. The impact of decreasing U.S. hip fracture rates on future hip fracture estimates. Osteoporos Int. 2013;24:2725–2728. doi: 10.1007/s00198-013-2375-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Hospital Discharge Survey (NHDS) Hospital discharges by first- and any-listed diagnosis: U.S., 1990-2010 (Source: NHDS) Available at: http://205.207.175.93/hdi/ReportFolders/ReportFolders.aspx?IF_ActivePath=P,18External Accessed May 10, 2015.

- 3.Magaziner J, Simonsick E, Kashner M, et al. Predictors of functional recovery one year following hospital discharge for hip fracture: A prospective study. J Gerontol. 1990;45:M101–M107. doi: 10.1093/geronj/45.3.m101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hannan EL, Magaziner J, Wang JJ, et al. Mortality and locomotion 6 months after hospitalization for hip fracture: Risk factors and risk-adjusted hospital outcomes. JAMA. 2001;285:2736–2742. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.21.2736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morrison RS, Magaziner J, McLaughlin MA, et al. The impact of post-operative pain on outcomes following hip fracture. Pain. 2003;103:303–311. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(02)00458-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheville A, Chen A, Oster G, et al. A randomized trial of controlled-release oxycodone during inpatient rehabilitation following unilateral total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83-A:572–576. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200104000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morrison RS, Magaziner J, Gilbert M, et al. Relationship between pain and opioid analgesics on the development of delirium following hip fracture. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2003;58:76–81. doi: 10.1093/gerona/58.1.m76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pasero CL, McCaffery M. Reluctance to order opioids in elders. Am J Nurs. 1997;97:20–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Strassels SA, Chen C, Carr DB. Postoperative analgesia: Economics, resource use, and patient satisfaction in an urban teaching hospital. Anesth Analg. 2002;94:130–137. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200201000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Management of Hip Fractures in the Elderly. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons; Rosemount: 2014. Strong evidence supports regional analgesia to improve preoperative pain control in patients with hip fracture; pp. 45–65. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abou-Setta AM, Beaupre LA, Rashiq S, et al. Comparative effectiveness of pain management interventions for hip fracture: A systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:234–245. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-4-201108160-00346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Akhtar S, Hwang U, Dickman E, et al. A brief educational intervention is effective in teaching the femoral nerve block procedure to first-year emergency medicine residents. J Emerg Med. 2013;45:726–730. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2013.04.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jeng CL, Torrillo TM, Anderson MR, et al. Development of a mobile ultrasound-guided peripheral nerve block and catheter service. J Ultrasound Med. 2011;30:1139–1144. doi: 10.7863/jum.2011.30.8.1139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morrison RS, Flanagan S, Fischberg D, et al. A novel interdisciplinary analgesic program reduces pain and improves function in older adults after orthopedic surgery. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57:1–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02063.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: Development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hamilton B, Langhlin J, Laughlin JA, et al. Interrater agreement of the seven-level functional independence measure (FIM) Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1991;72:790. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sheikh JI, Yesavage JA. Geriatric Depresion Scale (GDS): Recent evidence and development of a shorter version. Clin Gerontol. 1986;5:165–173. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stata Corporation . Stata (Version 13.1). College Station. Stata Corporation; Texas: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate - a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J Roy Stat Soc B Met. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thissen D, Steinberg L, Kuang D. Quick and easy implementation of the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure for controlling the false positive rate in multiple comparisons. J Educ Behav Stat. 2002;27:77–83. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Herrick C, Steger-May K, Sinacore DR, et al. Persistent pain in frail older adults after hip fracture repair. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:2062–2068. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52566.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hwang U, Richardson LD, Sonuyi TO, et al. The effect of emergency department crowding on the management of pain in older adults with hip fracture. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:270–275. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00587.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fletcher AK, Rigby AS, Heyes FL. Three-in-one femoral nerve block as analgesia for fractured neck of femur in the emergency department: A randomized controlled trial. Ann Emerg Med. 2003;41:227–233. doi: 10.1067/mem.2003.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Foss NB, Kristensen BB, Bundgaard M, et al. Fascia iliaca compartment blockade for acute pain control in hip fracture patients: A randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Anesthesiology. 2007;106:773–778. doi: 10.1097/01.anes.0000264764.56544.d2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haddad FS, Williams RL. Femoral nerve block in extracapsular femoral neck fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1995;77:922–923. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Godoy Monzon D, Vazquez J, Jauregui JR, et al. Pain treatment in post-traumatic hip fracture in the elderly: Regional block vs systemic non-steroidal analgesics. Int J Emerg Med. 2010;3:321–325. doi: 10.1007/s12245-010-0234-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mouzopoulos G, Vasiliadis G, Lasanianos N, et al. Fascia iliaca block prophylaxis for hip fracture patients at risk for delirium: A randomized placebo-controlled study. J Orthop Traumatol. 2009;10:127–133. doi: 10.1007/s10195-009-0062-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yun MJ, Kim YH, Han MK, et al. Analgesia before a spinal block for femoral neck fracture: Fascia iliaca compartment block. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2009;53:1282–1287. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2009.02052.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morrison RS, Meier DE, Fischberg D, et al. Improving the management of pain in hospitalized adults. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1033–1039. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.9.1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Corell AJ, Vlassakov KV, Kissin I. No evidence of real progress in treatment of acute pain, 1993–2012: Scientometric analysis. J Pain Res. 2014;7:199–2010. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S60842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morrison RS, Siu AL. A comparison of pain and its treatment in advanced dementia and cognitively intact patients with hip fracture. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2000;19:240–248. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(00)00113-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.American College of Emergency Medicine Emergency Ultrasound Guidelines. Policy Statement. 2008 Available at: http://www.acep.org/workarea/DownloadAsset.aspx?id=32878 Accessed June 2, 2015.