Abstract

Background/Objectives

To establish the rate of new and continuation benzodiazepine use among older adults seen by non-psychiatrist physicians, as well as identify patient subpopulations at risk for new and continuation benzodiazepine use.

Design, Setting, Participants

Cross-sectional analysis of the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (2007–2010) of all visits by adults to office-based non-psychiatrist physicians (n=98,818), then limited to those at which a benzodiazepine was prescribed (new or continuation).

Measurements

Percentage of benzodiazepine visits among all outpatient encounters by patient age and corresponding annual visit rate per 1,000 population. Analysis was then limited to adults ≥65; demographic, clinical, and visits characteristics were used to compare visits of benzodiazepine users with non-users and continuation users with new users.

Results

The proportion of benzodiazepine visits ranged from 3.2% (95% confidence interval [CI] 2.7–3.7%) among those 18–34 up to 6.6% (CI 5.8–7.6%) among adults ≥80 and the proportion of continuation visits increased with age, rising to 90.2% (CI 86.2–93.1%) among those ≥80. The population-based visit rate ranged from 61.7 (CI 50.7–72.7) per 1,000 persons among the youngest adults to 463.7 (CI 385.4–542.0) among those ≥80. Only 16.0% (CI 13.5–18.8%) of continuation users had any mental health diagnosis. Among all benzodiazepine users, less than 1% (CI .4–1.8%) were provided or referred to psychotherapy, while 10.0% (CI 7. 2–13.3%) were also prescribed an opioid.

Conclusion

In the US, few older adult benzodiazepine users receive a clinical mental health diagnosis and almost none are provided or referred to psychotherapy. Prescribing to older adults continues despite decades of evidence documenting safety concerns, effective alternative treatments, and effective methods for tapering even chronic users.

Keywords: benzodiazepine, psychotropic, insomnia, anxiety

INTRODUCTION

Benzodiazepine use in the United States is common and increases with age. In a recent analysis, 8.7% of US adults aged 65–80 years were prescribed benzodiazepines over the course of one year.1 Benzodiazepines are most commonly used for anxiety and insomnia, even though psychotherapy and alternative medications are recommended preferentially.2–4 Use is a particular concern among older adults, given associations of benzodiazepines with a variety of adverse outcomes including falls5, fractures6, motor vehicle accidents7, impaired cognition8,9, and increased risk of dementia.10 Due to the accumulation of health and safety concerns in older adults, the American Geriatrics Society (AGS) Beers Criteria include a “strong” recommendation to avoid any type of benzodiazepine for the treatment of insomnia or agitation, allowing that use may be appropriate only for a few select indications, including severe generalized anxiety disorder unresponsive to other therapies.11 As part of the Choosing Wisely Campaign, the AGS identified use of benzodiazepines in older adults as one of ten things physicians and patients should question.12

A recent analysis of national benzodiazepine prescribing highlighted a rate of long-term use (≥120 days of medication dispensed during the year) that increased with age, growing to nearly one-third of use among those 65–80 years. This high rate—among older adults at particular risk of harm—reflects the challenges perceived by patients and providers around discontinuing long-term benzodiazepines.13,14 In addition to considering whether use is short- or long-term, interventions to reduce benzodiazepine use in older adults may need to be tailored around factors such as indication for the prescription and patient engagement in psychotherapy. Prior studies based on patient self-report of relatively small regional samples have suggested that insomnia15 and anxiety16 are the primary reasons for a benzodiazepine prescription, though the research varied in the most commonly cited diagnosis. The extent to which benzodiazepine users engage in psychotherapy is critical, as psychotherapy has been shown effective in facilitating benzodiazepine taper17, especially in older patients whose indication for use was insomnia.18,19

Prior work on prevalence of benzodiazepine use in the U.S. is based on data collected over 20 years ago,20–22 while the recent national prescription analysis had limited encounter-level clinical information.1 To our knowledge, there are no previous studies of benzodiazepine use that include information about psychotherapy. This article uses data from the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS), which is a representative survey of visits to all office-based physicians in the U.S. We focus on non-psychiatric physicians, who provide the vast majority of benzodiazepine prescriptions to adults, including nearly 95% of those to older adults.1 We describe the proportion and population-based rate of visits where a benzodiazepine is prescribed among adult outpatient visits, stratified by age group. In order to identify clinical subpopulations at risk for benzodiazepine therapy and for whom to focus discontinuation initiatives, we examine demographic, clinical, and visit characteristics associated with benzodiazepine use. Finally, we examine how continuation benzodiazepine users differ from new users, in order to focus efforts that limit conversion to long-term use.

METHODS

Sample

These analyses use NAMCS (administered by the National Center for Health Statistics [NCHS; Hyattsville, MD]) years 2007–2010. NAMCS is a national probability sample survey of office-based physicians designed to “provide objective, reliable information about the provision and use of ambulatory medical care services in the United States.”23 Physicians are sampled from the American Medical Association and American Osteopathic Association master files. The specialties of anesthesiology, pathology, and radiology are excluded from the survey, as are encounters such as house calls or those to institutional settings (e.g., nursing homes).

Each physician is randomly assigned to a one-week reporting period, with data collected from a systematic random sample of visits during that week. Data for selected visits is recorded by the physician or office staff on a standardized form and includes patient age, sex, and race/ethnicity. The overall physician response rate over the four years ranged from 58.3% to 62.1% and yielded a total of 125,029 patient encounters. Adjusting for key survey design elements allows analyses to represent total annual visits to US office-based physicians.24

Benzodiazepines and Other Medications

Survey data includes up to 8 medications that are prescribed, ordered, supplied, administered, or continued during each visit. Patient visits were considered a “benzodiazepine visit” if the medication list included any of the following: alprazolam, chlordiazepoxide, clonazepam, clorazepate, diazepam, estazolam, flurazepam, halazepam, lorazepam, midazolam, oxazepam, prazepam, quazepam, temazepam, or triazolam. Each visit was classified into whether the benzodiazepine was newly-prescribed at that visit or continued (i.e., previously prescribed), as well as whether they included other commonly prescribed psychoactive medications, including antidepressants, antipsychotics, and opioids (Appendix, eTable 1). We also calculated the total number of continued medications at the visit (excluding benzodiazepines).

Diagnosis and Reason for Visit

Up to three visit diagnoses are recorded (using the International Classification of Disease, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-9-CM]) along with up to three things the patient describes as their most important reason for the visit, which are coded by survey field staff using a classification system developed by NCHS.25 We identified encounters for anxiety, insomnia, depression, substance use disorders, dementia, and any mental health diagnosis or reason for visit (eTable 2).

Beyond the ≤3 specific visit-related diagnoses, NAMCS collects data on several chronic conditions at all visits, which we include to more fully capture medical comorbidity: asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cerebrovascular or ischemic heart disease, hypertension or hyperlipidemia, congestive heart failure, obesity, osteoporosis, and tobacco use.

Provider and Visit Characteristics

NAMCS classifies providers into fifteen specialty groups. Analysis was limited to non-psychiatric providers, grouped as: family medicine, internal medicine, other medical specialty. Other visit-related information used for analysis included: 1) whether the visit was a return visit; 2) how many times the patient had been seen in previous 12 months; 3) whether the visit was to address a chronic problem; 4) whether a return visit was scheduled; 5) whether psychotherapy or other mental health counseling was provided or ordered; 6) whether stress management health education was provided or ordered; and 7) visit duration (minutes of face-to-face contact).

Statistical Methods

We limited the sample to visits to non-psychiatrist physicians by patients ≥18 across the 2007–2010 interval (n=98,818), stratified by age (18–34, 35–49, 50–64, 65–79, ≥80), and then generated national benzodiazepine visit estimates and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI). Analyses were adjusted using survey design elements provided by NCHS for visit weight, clustering within physician practice, and stratification to allow national inferences.24 Survey years were combined as recommended by NCHS to produce more reliable annual visit rate estimates.26 We estimated the proportion these benzodiazepine visits represented of all office-based physicians’ visits, and the proportion of visits that were new versus continuation treatment. Using denominators (i.e., non-institutionalized population for each age group) obtained from US Census estimates27, we generated annual visit rates per 1,000 population.

We then limited analysis to adults ≥65 (n=32,544) and used logistic regression to test the association of individual characteristics with benzodiazepine therapy. We compared any benzodiazepine prescribing (dependent variable: 0=nonuser, 1=user) and type of prescribing (dependent variable: 0=new, 1=continuation). We used multivariable logistic regression to adjust for anxiety and insomnia, the key clinical indications for which benzodiazepines are prescribed.

Patients may have multiple conditions addressed during a visit, but NAMCS only collects information on up to three diagnoses and three patient-reported visit reasons. We conducted a sensitivity analysis of the association between diagnoses and visit types by limiting analysis to visits with ≤2 diagnoses or patient-reported reasons for visit (eTable 3 & 4). Analyses were conducted in Stata 13.1 (College Station, TX) using two-sided tests with α = .05.

RESULTS

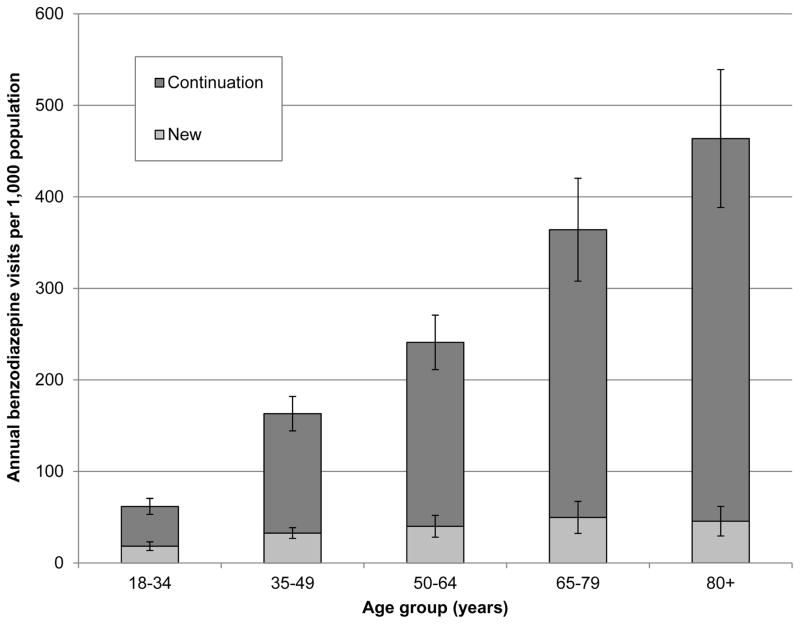

Benzodiazepines were prescribed at 5.6% (CI 5.2–6.0%) of adult outpatient physician visits, representing approximately 20.4 (CI 17.0–23.9) million visits annually. The percentage of visits at which new benzodiazepines were prescribed decreased with age, while continuation benzodiazepine use accounted for an increasingly large proportion (Table 1). The per-population benzodiazepine visit rate was lowest for young adults (61.7 [CI 50.7–72.7] per 1,000 persons) and increased markedly with age to 463.7 (CI 385.4–542.0) among the oldest adults (Figure 1). The rate of new benzodiazepine visits was relatively constant across age groups; the increase in the overall benzodiazepine visit rate among older adults was largely due to the increasing rate of continuation visits.

Table 1.

Benzodiazepine visits among all adults to office-based non-psychiatric physicians in the U.S. from 2007–2010 (n=98,818)

| Age (y)

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18–34 | 35–49 | 50–64 | 65––79 | 80+ | F | p | |

| Overall number of visits, n | 17,156 | 21,447 | 27,671 | 22,895 | 9649 | ||

| Benzodiazepine visits, n | 547 | 1,271 | 1,639 | 1,194 | 554 | ||

| Benzodiazepine visits, %a | 3.2 | 6.2 | 6.2 | 5.6 | 6.6 | 23.8 | <.001 |

| 95% CI | 2.7––3.7 | 5.7–6.8 | 5.6–6.9 | 4.9–6.3 | 5.8–7.6 | ||

| Continuation visits, %b | 70.3 | 80.0 | 83.4 | 86.3 | 90.2 | 9.3 | <.001 |

| 95% CI | 64.0–75.9 | 76.9–82.8 | 78.6–87.2 | 81.7–90.0 | 86.2–93.1 | ||

| New visits, % | 29.8 | 20.0 | 16.6 | 13.7 | 9.8 | ||

| 95% CI | 24.1–36.1 | 17.3–23.1 | 12.8–21.4 | 10.1–18.3 | 6.9–13.9 | ||

weighted percentage of overall visits

weighted percentage of all benzodiazepine visits (e.g., among encounters at which a benzodiazepine was prescribed among those 18–34, 70.3% were continuation prescriptions).

New and continuation percentages within age groups may not add to 100% due to rounding.

Figure 1.

Annual population-based visit rates by age group for new and continuation benzodiazepine use among patients of non-psychiatrist physicians in the U.S. from 2007–2010 (n=5,205).

Benzodiazepine users were more likely to be older and female compared to non-users (Table 2). Benzodiazepine users had higher rates of mental health diagnoses or reasons for visit, though overall, relatively few visits had such diagnoses (Table 3). Just 8.2% (CI 6.4–10.5%) of benzodiazepine users had anxiety as a diagnosis or visit reason; 3.5% (CI 2.5–4.9%) reported insomnia. In the sensitivity analysis limited to visits with ≤2 diagnoses or visit reasons, similar associations between diagnosis and benzodiazepine use were observed (eTable 3).

Table 2.

Association of demographic characteristics with any and continuation benzodiazepine use among older adult patients of non-psychiatrist physicians in the U.S. from 2007–2010 (n=32,544 and n=1,748)

| Adjusteda

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic Characteristic | Visits with benzodiazepines (n=1,748) | Visits without benzodiazepines (n=30,796) | p | ORb | 95% CI |

| Age | |||||

| 65–74 years, %c (ref) | 45.3 | 50.0 | n/a | 1.00 | n/a |

| 75–84 years | 38.5 | 37.0 | .05 | 1.16 | 1.01–1.33 |

| 85+ years | 16.2 | 13.0 | .006 | 1.40 | 1.12–1.77 |

| Sex | |||||

| Male (ref) | 31.7 | 43.7 | n/a | 1.00 | n/a |

| Female | 68.3 | 56.3 | <0.001 | 1.61 | 1.38–1.88 |

| Ethnicity | |||||

| Non-Hispanic white (ref) | 82.5 | 79.8 | n/a | 1.0 | n/a |

| Non-Hispanic black | 7.1 | 8.1 | .29 | .87 | .67–1.13 |

| Hispanic | 8.3 | 8.9 | .96 | .99 | .76–1.30 |

| Other | 2.1 | 4.0 | .005 | .52 | .33–.82 |

| Adjusteda

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic Characteristic | Continuation benzodiazepines (n=1,559) | New benzodiazepines (n=189) | p | ORd | 95% CI |

| Age | |||||

| 65–74 years, % (ref) | 44.8 | 49.0 | n/a | 1.00 | n/a |

| 75–84 years | 38.0 | 41.6 | .99 | .95 | .62–1.45 |

| 85+ years | 17.2 | 9.3 | .09 | 1.96 | .82–4.67 |

| Sex | |||||

| Male (ref) | 31.2 | 35.2 | n/a | 1.00 | n/a |

| Female | 68.8 | 64.8 | .55 | 1.21 | .66–2.22 |

| Ethnicity | |||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 83.6 | 75.3 | n/a | 1.00 | n/a |

| Non-Hispanic black | 6.2 | 13.6 | .009 | .38 | .18–.78 |

| Hispanic | 8.4 | 7.4 | .96 | 1.14 | .45–2.90 |

| Other | 1.9 | 3.7 | .11 | .39 | .15–1.06 |

Adjusted for diagnosis or reason for visit of anxiety and insomnia.

OR: odds ratio reflecting the odds associated with benzodiazepine use.

Percentage of visit with a given characteristic, unless noted otherwise.

Reflects the odds associated with continuation benzodiazepine use.

Table 3.

Association of clinical and visit characteristics with benzodiazepine use among older adult patients of non-psychiatrist physicians in the U.S. from 2007–2010 (n=32,544)

| Adjusteda

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical Characteristic | Visits with benzodiazepines (n=1,748) | Visits without benzodiazepines (n=30,796) | p | ORb | 95% CI |

| Diagnoses/visit complaint | |||||

| Anxiety, %c | 8.2 | .8 | <.001 | 10.74 | 7.69–15.00 |

| Insomnia | 3.5 | .7 | <.001 | 4.22 | 2.82–6.30 |

| Depression | 5.2 | 1.3 | <.001 | 3.09 | 2.12–4.52 |

| Dementia | .5 | .5 | .77 | 1.11 | .46–2.67 |

| Substance use disorder | .5 | .2 | .11 | 1.68 | .66–4.29 |

| Any mental health diagnosis | 19.0 | 4.8 | <.001 | 2.77 | 2.17–3.54 |

| Medical conditions | |||||

| Asthma/COPD | 18.2 | 11.7 | <.001 | 1.71 | 1.38–2.11 |

| CVA/CAD | 16.7 | 13.6 | .005 | 1.28 | 1.09–1.52 |

| HTN/HL | 67.5 | 58.2 | <.001 | 1.50 | 1.26–1.78 |

| CHF | 5.7 | 5.0 | .27 | 1.17 | .92–1.49 |

| Obesity | 5.4 | 5.9 | .54 | .94 | .69–1.29 |

| Osteoporosis | 9.8 | 6.3 | <.001 | 1.56 | 1.26–1.93 |

| Tobacco-user | 8.8 | 5.7 | <.001 | 1.57 | 1.22–2.02 |

| Other psychotropic medication | |||||

| Antidepressant | 26.9 | 7.8 | <.001 | 3.93 | 3.40–4.55 |

| Antipsychotic | 2.6 | .8 | <.001 | 3.41 | 2.16–5.39 |

| Opioid | 10.0 | 2.9 | <.001 | 3.71 | 2.63–5.24 |

| Mean total continued medications (SEMd) | 4.6 (.1) | 3.6 (.1) | <.001 | 1.1 | 1.1–1.16 |

| Visit Characteristic | |||||

|

| |||||

| Psychotherapy | .9 | .3 | .009 | 1.68 | .74–3.82 |

| Stress management | 3.6 | 1.2 | <.001 | 2.04 | 1.28–3.27 |

| Provider | |||||

| Family practice (ref) | 24.5 | 18.0 | n/a | 1.00 | n/a |

| Internal Medicine | 30.6 | 21.8 | .75 | 1.05 | .84–1.31 |

| Other medical specialty | 44.9 | 60.2 | <.001 | .63 | .51–.77 |

| Return visit with provider (ref: new patient) | 91.8 | 90.1 | .28 | 1.12 | .84–1.50 |

| Visit for a chronic condition (ref: no) | 56.0 | 52.7 | .09 | 1.13 | .97–1.32 |

| Visit disposition: scheduled follow-up (ref: no) | 78.1 | 77.2 | .56 | 1.05 | .89–1.25 |

| Mean number of visits in past 12 months (SEM) | 5.2 (.2) | 4.3 (.1) | <.001 | 1.03 | 1.02–1.04 |

| Mean time with physician, min (SEM) | 20.9 (.8) | 19.9 (.3) | .08 | 1.00 | 1.00–1.01 |

Adjusted for diagnosis or reason for visit of anxiety and insomnia.

OR: odds ratio, reflecting the odds associated with benzodiazepine use.

Percentage of visit with a given characteristic, unless noted otherwise.

SEM: standard error of the mean.

Over one-quarter (CI 24.6–29.3%) of visits by patients prescribed benzodiazepines included antidepressants; 10.0% (CI 7.4–13.3%) included an opioid. An extremely small proportion of benzodiazepine visits included psychotherapy or stress management health education: just .8% (CI .4–1.8%) and 3.6% (CI 2.2–5.9%), respectively.

Benzodiazepine visits were by patients who appeared to be more medically ill, with higher proportions of chronic conditions, more visits within the past 12 months, and receipt of more prescription medications.

Comparing continuation and new benzodiazepine visits, there was no association by age or gender (Table 2). However, the odds of continuation use at a visit for a non-Hispanic black patient were significantly lower than for a non-Hispanic white patient, as the proportion of new benzodiazepine use by non-Hispanic black patients was higher relative to continuation use. Visits by continuation and new users were largely similar across clinical and visit characteristics, but visits by continuation benzodiazepine users were far less likely to have any mental health diagnosis, anxiety, or insomnia (Table 4). When comparisons between new and continuation visits were limited to visits with ≤2 diagnoses or reasons (eTable 4), the overall difference and statistical significance was little changed from results in the full sample.

Table 4.

Association of clinical and visit characteristics with continuation versus new benzodiazepine use among older adult patients of non-psychiatrist physicians in the U.S. from 2007–2010 (n=1,748)

| Adjusteda

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical Characteristic | Continuation benzodiazepines (n=1,559) | New benzodiazepines (n=189) | p | ORb | 95% CI |

| Diagnoses/visit complaint | |||||

| Anxiety, %c | 6.4 | 21.3 | <.001 | .29 | .16–.50 |

| Insomnia | 2.3 | 11.6 | <.001 | .22 | .08–.65 |

| Depression | 5.0 | 6.4 | .54 | .95 | .37–2.47 |

| Dementia | .6 | .2 | .11 | 2.90 | .58–14.54 |

| Substance use disorder | .4 | 1.1 | .35 | .43 | .03–6.55 |

| Any mental health diagnosis | 16.0 | 40.3 | <.001 | .48 | .26–.89 |

| Medical conditions | |||||

| Asthma/COPD | 19.2 | 10.6d | .05 | 1.80 | .87–3.74 |

| CVA/CAD | 17.3 | 12.2 | .20 | 1.30 | .68–2.48 |

| HTN/HL | 67.2 | 69.9 | .54 | .85 | .54–1.32 |

| CHF | 5.9 | 4.3 | .62 | 1.22 | .37–4.02 |

| Obesity | 5.4 | 5.4 | .99 | .89 | .48–1.65 |

| Osteoporosis | 9.5 | 11.8 | .40 | .76 | .43–1.35 |

| Tobacco-user | 8.7 | 9.3 | .85 | .87 | .43–1.75 |

| Other psychotropic medication | |||||

| Antidepressant | 28.4 | 16.4 | .007 | 2.05 | 1.22–3.46 |

| Antipsychotic | 2.8 | 1.2 | .41 | 1.94 | .26–14.67 |

| Opioid | 8.7 | 19.3 | .10 | .31 | .10–.96 |

| >1 benzodiazepine | 3.8 | 7.9d | .03 | .46 | .22–.94 |

| Mean total continued medications (SEMd) | 4.9 (.1) | 2.2 (.3) | <.001 | 1.6 | 1.41–1.84 |

| Visit Characteristic | |||||

|

| |||||

| Psychotherapy | .9 | 1.0 | .90 | 1.66 | .23–12.03 |

| Stress management | 2.8 | 9.0 | .002 | .50 | .19–1.34 |

| Provider | |||||

| Family practice (ref) | 23.6 | 30.4 | n/a | 1.00 | n/a |

| Internal Medicine | 31.0 | 27.8d | .17 | 1.38 | .78–2.46 |

| Other medical specialty | 45.4 | 41.7 | .31 | 1.08 | .56–2.11 |

| Return visit with provider (ref: new patient) | 92.2 | 85.4 | .24 | 2.56 | .79–8.29 |

| Visit for a chronic condition (ref: no) | 56.8 | 50.3 | .22 | 1.42 | .92–2.19 |

| Visit disposition: scheduled follow-up (ref: no) | 79.1 | 71.3 | .10 | 1.53 | .87–2.70 |

| Mean number of visits in past 12 months (SEM) | 5.3 (.2) | 4.4 (.4) | .13 | 1.04 | .99–1.10 |

| Mean time with physician, min (SEM) | 20.6 (.9) | 22.7 (1.4) | .30 | .99 | .98–1.00 |

Adjusted for diagnosis or reason for visit of anxiety and insomnia.

OR: odds ratio, reflecting the odds associated with continuation benzodiazepine use.

Percentage of visit with a given characteristic, unless noted otherwise.

SEM: standard error of the mean.

Relative to patients at a new benzodiazepine visit, patients at a continuation visit were more likely to receive an antidepressant, equally (un)likely to receive or be referred to psychotherapy, and less likely to receive stress management health education.

Continuation users were on a larger number of other medications, but had a similar level of medical comorbidity compared to new users with the exception of asthma or COPD, which was more common among continuation visits. There were no statistically significant differences between the new and continuation groups by provider type or other visit characteristics.

DISCUSSION

Our analyses demonstrate that the population-based rate of new benzodiazepine use in US office-based medical practice is generally consistent across adult age groups. Despite evidence of the harms associated with benzodiazepine use in older adults, efficacy of alternative pharmaco- and psychotherapies2–4,28, and professional guidelines advising against benzodiazepines,11,12 initiation continues unabated and continuation prescriptions account for a growing proportion of use with older age.

Prior work has suggested that benzodiazepine use in older adults is primarily for anxiety or insomnia.15,16,22 Our findings confirm that anxiety or insomnia are the most common diagnoses or reasons reported for a benzodiazepine visit, at 21.3% and 11.6% of new benzodiazepine visits, respectively. However, there was no mental health related diagnosis or patient reason for visit reported in over 80% of all benzodiazepine visits and in nearly 60% of visits where a new benzodiazepine was started. It may be that some benzodiazepines are started for brief stress or adjustment reactions, which clinicians are not recording as a diagnosis. In a previous analysis of community-dwelling patients newly started on an anxiolytic, the most common reason reported after anxiety or insomnia was “stressful life event, adjustment, [or] grief.”16 However, if the patient reported a visit reason such as “stress” or “tension”, this should have been captured in the survey data (eTable 2, code 1100.0). Another possibility is that older adults may not report anxiety, but rather a variety of somatic symptoms.29 Providers may conceptualize and treat such symptoms as anxiety, but do not label them as such. The continuation benzodiazepine user appears to be taking “benzodiazepine[s] for less specific indications” than well-defined psychiatric disorders, as noted by Simon et al. in 1996.22

What is perhaps most notable—and has not previously been reported to our knowledge—is the extremely small proportion of patients that received or were referred to psychotherapy. Cognitive behavioral therapy28,30, short-term psychodynamic therapy31, and other psychosocial treatments29 are all effective for anxiety disorders, while cognitive behavioral therapy is effective for insomnia.4 Despite the efficacy of psychotherapy to treat the most common conditions for which benzodiazepines are prescribed, less than 1 percent of both overall and new benzodiazepine visits included provision of or referral to psychotherapy. Non-psychiatrist physicians may benefit from additional education about the effectiveness of evidence-based psychotherapies and, perhaps more importantly, improved access for their patients to such treatments. NAMCS may underestimate the provision of psychotherapy, since patients may be engaged in psychotherapy with another provider or psychotherapy may have been previously discussed and or attempted.

In addition, non-physician providers provide a significant amount of psychotherapy, which NAMCS does not capture. However, adults over 65 have the lowest rates of psychotherapy use of any age group, and the NAMCS-based rate is similar to a previous analysis of psychotherapy using the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey.32 In addition to psychotherapy as an alternative to benzodiazepines, selective-serotonin reuptake inhibitors are considered first-line pharmacotherapy for anxiety disorders.33,34 Among all benzodiazepine visits, just a quarter of patients were on an antidepressant. The low proportion of patients receiving psychotherapy and the relatively low proportion of those on antidepressants suggest that older adults are not receiving treatments that are both more appropriate and safer.

Nearly 10% of those prescribed a benzodiazepine were also prescribed an opioid, while co-prescription of antipsychotics occurred in 3% of older adults. Co-prescribing of such CNS-active medications is associated with cognitive decline,35 while use singly5,6,36 or in combination11 is associated with an increased risk of falls and fractures. An added concern is the combined role in pharmaceutical overdose deaths. Individually, opioids and benzodiazepines are involved in over 75% of pharmaceutical overdose deaths.37 Among opioid-related deaths, which are the leading type of pharmaceutical death, benzodiazepines are the most commonly co-prescribed medication, involved in 30% of deaths. While combination use of these agents may be appropriate in select patient populations, use should be considered only after fully discussing potential risks, benefits, and alternatives with patients.

Comparing new to continuation benzodiazepine users on other clinical characteristics, there are relatively few differences. A larger proportion of continuation users have asthma or COPD, which is consistent with the high prevalence of anxiety disorders among patients with chronic respiratory problems,38 though it is also possible that respiratory symptoms may be misattributed to anxiety, leading to benzodiazepine treatment. Nonetheless, use of benzodiazepines in patients with COPD is concerning given the association with increased mortality.39

Likewise, there are relatively few visit characteristics that distinguish between benzodiazepine users and nonusers or new and continuation users. Visits with benzodiazepine users were slightly longer than those with non-users, and new visits were slightly longer than continuation visits, but neither comparison was statistically significant or clinically meaningful. There was no difference by visit disposition, nor by whether the patient was established with the practice. Those on a benzodiazepine had more visits in the prior 12 months than nonusers, which is consistent with their higher overall medical comorbidity, but there was no difference between new and continuation benzodiazepine users.

Our work has several limitations. First, patient-level clinical assessments of current symptoms and function are not available. Second, visit diagnoses are limited to three, so in patients with more active problems, there may be information bias that differentially affects the various benzodiazepine groups. However, when limiting analysis to encounters with no more than two diagnoses or visit reasons, the associations between diagnoses and benzodiazepine use were virtually unchanged. Third, NAMCS does not account for whether a prescribed medication is taken regularly versus as needed, so it is possible that the extent of use is overestimated. However, as only 8 medications are recorded, benzodiazepine use may also be underestimated. Fourth, as NAMCS is a survey of office-based practice, it does not include physicians practicing in other settings. While physician non-response might introduce bias into the results, the survey weights designed by NAMCS account for this to produced unbiased national estimates.24 Finally, while the analysis was limited to non-psychiatrist physicians, it is possible that some of the continuation benzodiazepines were initially prescribed by psychiatrists. However, as nearly 95% of new benzodiazepines prescribed to older adults are by non-psychiatrists1, the psychiatrist-initiated group likely accounts for an extremely small subset.

These nationally-representative analyses largely confirm and update analyses utilizing data from over 20 years ago by demonstrating that: benzodiazepine initiation continues into late life; continuation use increases with age; and they are prescribed for purposes other than clearly defined mental disorders.22,40 How do we explain continued use of a potentially harmful intervention, in the face of extensive evidence that alternatives are both effective and more safe? Cook et al. 13,14, working with older adults that were chronic benzodiazepine users, suggest patients doubted that “[any]thing other than the benzodiazepine” would help and generally rejected the idea of psychological interventions. The majority of physicians “believed that attempting withdrawal would be time-consuming and likely futile.” These attitudes are frustrating given the growing evidence that older patients, even those with chronic use, can successfully decrease and be tapered off benzodiazepines using interventions including cognitive behavioral therapies and direct-to-consumer educational techniques.17–19,41 As attitudes about mental health disorders and treatment change, it may be that older adults will become more willing to consider psychotherapeutic treatment options, though this will not be helpful if patients have no access to specialty mental health services.42

While patients may be reluctant to stop long-term benzodiazepine use, a physician’s fundamental responsibility is to the safety of his or her patient. The majority of use appears to be in the absence of a clearly-defined mental disorder, with limited use of alternative and safer treatments such as antidepressants or psychotherapy. While clicking “reorder” may limit short-term patient (and provider) distress, critical concerns exist over the appropriateness and safety of most long-term benzodiazepine use in older adults in the United States. New strategies are needed to encourage patients and providers to discontinue potentially inappropriate benzodiazepine therapy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding Source: This work was supported by the Beeson Career Development Award Program (NIA K08AG048321, AFAR, The John A. Hartford Foundation, and The Atlantic Philanthropies).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: Dr. Olfson is principal investigator of a grant to Columbia University from Sunovion Pharmaceuticals. Otherwise, the authors have no conflicts to disclose.

Author Contributions: DTM acquired and analyzed the data and prepared the first draft of this manuscript. All authors edited the manuscript, helped interpret the results, and guided additional study questions.

Sponsor’s Role: none.

References

- 1.Olfson M, King M, Schoenbaum M. Benzodiazepine Use in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(2):136–142. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.1763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baldwin D, Woods R, Lawson R, Taylor D. Efficacy of drug treatments for generalised anxiety disorder: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2011;342:d1199. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith MT, Perlis ML, Park A, et al. Comparative meta-analysis of pharmacotherapy and behavior therapy for persistent insomnia. Am J Psychiatry. 2014;159(1):5–11. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu JQ, Appleman ER, Salazar RD, Ong JC. Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia comorbid with psychiatric and medical conditions: A meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2015 doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.3006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Woolcott JC, Richardson KJ, Wiens MO, et al. Meta-analysis of the impact of 9 medication classes on falls in elderly persons. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(21):1952–1960. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang PS, Bohn RL, Glynn RJ, Mogun H, Avorn J. Hazardous benzodiazepine regimens in the elderly: effects of half-life, dosage, and duration on risk of hip fracture. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158(6):892–898. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.6.892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dassanayake T, Michie P, Carter G, Jones A. Effects of benzodiazepines, antidepressants and opioids on driving. Drug Saf. 2011;34(2):125–156. doi: 10.2165/11539050-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tannenbaum C, Paquette A, Hilmer S, Holroyd-Leduc J, Carnahan R. A systematic review of amnestic and non-amnestic mild cognitive impairment induced by anticholinergic, antihistamine, GABAergic and opioid drugs. Drugs Aging. 2012;29(8):639–658. doi: 10.1007/BF03262280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paterniti S, Dufouil C, Alpérovitch A. Long-term benzodiazepine use and cognitive decline in the elderly: the Epidemiology of Vascular Aging Study. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2002;22(3):285–293. doi: 10.1097/00004714-200206000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Billioti de Gage S, Moride Y, Ducruet T, et al. Benzodiazepine use and risk of Alzheimer's disease: case-control study. BMJ. 2014;349:g5205. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g5205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.American Geriatrics Society. Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2015 updated Beers Criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015 doi: 10.1111/jgs.13702. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.American Geriatrics Society. Choosing Wisely Website. [Accessed July 13, 2015];Ten things physicians and patients should question. http://www.choosingwisely.org/societies/american-geriatrics-society/

- 13.Cook JM, Biyanova T, Masci C, Coyne JC. Older patient perspectives on long-term anxiolytic benzodiazepine use and discontinuation: a qualitative study. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(8):1094–1100. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0205-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cook JM, Marshall R, Masci C, Coyne JC. Physicians’ perspectives on prescribing benzodiazepines for older adults: a qualitative study. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(3):303–307. doi: 10.1007/s11606-006-0021-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Simon GE, Ludman EJ. Outcome of new benzodiazepine prescriptions to older adults in primary care. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2006;28(5):374–378. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2006.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maust DT, Mavandadi S, Eakin A, et al. Telephone-based behavioral health assessment for older adults starting a new psychiatric medication. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011;19(10):851–858. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e318202c1dc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gould RL, Coulson MC, Patel N, Highton-Williamson E, Howard RJ. Interventions for reducing benzodiazepine use in older people: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Br J Psychiatry. 2014;204:98–107. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.113.126003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baillargeon L, Landreville P, Verreault R, Beauchemin J-P, Grégoire J-P, Morin CM. Discontinuation of benzodiazepines among older insomniac adults treated with cognitive-behavioural therapy combined with gradual tapering: a randomized trial. Can Med Assoc J. 2003;169(10):1015–1020. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morin C, Bastien C, Guay B, Radouco-Thomas M, Leblanc J, Vallières A. Insomnia and chronic use of benzodiazepines: A randomized clinical trial of supervised tapering, cognitive-behavior therapy, and a combined approach to facilitate benzodiazepine discontinuation. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:332–342. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.2.332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gray SL, Eggen AE, Blough D, Buchner D, LaCroix AZ. Benzodiazepine Use in Older Adults Enrolled in a Health Maintenance Organization. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2003;11(5):568–576. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gleason PP, Schulz R, Smith NL, et al. Correlates and prevalence of benzodiazepine use in community-dwelling elderly. J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13(4):243–250. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1998.00074.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Simon GE, Vonkorff M, Barlow W, Pabiniak C, Wagner E. Predictors of chronic benzodiazepine use in a health maintenance organization sample. J Clin Epidemiol. 1996;49(9):1067–1073. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(96)00139-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. About the Ambulatory Health Care Surveys: National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/ahcd/about_ahcd.htm.

- 24.National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2010 NAMCS Micro-data file documentation. ftp://ftp.cdc.gov/pub/Health_Statistics/NCHS/Dataset_Documentation/NAMCS/doc2010.

- 25.Schneider D, Appleton L, McLemore T. Vital and health statistics. National Center for Health Statistics, Public Health Service; Hyattsville, MD: 1979. A reason for visit classification for ambulatory care, United States. Series 2, No. 78. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/series/sr_02/sr02_078.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hsiao C-J National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Understanding and using NAMCS and NHAMCS data: data tools and basic programming techniques. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/ppt/nchs2010/03_Hsiao.pdf.

- 27.United States Census Bureau, US Department of Commerce. Population estimates: population and housing unit estimates. http://www.census.gov/popest/index.html.

- 28.Gould RL, Coulson MC, Howard RJ. Efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety disorders in older people: A meta-analysis and meta-regression of randomized controlled trials. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(2):218–229. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03824.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wetherell JL, Lenze EJ, Stanley MA. Evidence-based treatment of geriatric anxiety disorders. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2005;28(4):871–896. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2005.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Covin R, Ouimet AJ, Seeds PM, Dozois DJ. A meta-analysis of CBT for pathological worry among clients with GAD. J Anxiety Disord. 2008;22(1):108–116. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2007.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leichsenring F, Salzer S, Jaeger U, et al. Short-term psychodynamic psychotherapy and cognitive-behavioral therapy in generalized anxiety disorder: a randomized, controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166(8):875–881. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09030441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Olfson M, Marcus SC, Druss B, Pincus HA. National Trends in the Use of Outpatient Psychotherapy. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(11):1914–1920. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.11.1914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with panic disorder. American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: 2010. http://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/panicdisorder.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bandelow B, Zohar J, Hollander E, et al. World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of anxiety, obsessive-compulsive and post-traumatic stress disorders–first revision. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2008;9(4):248–312. doi: 10.1080/15622970802465807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wright RM, Roumani YF, Boudreau R, et al. Effect of central nervous system medication use on decline in cognition in community-dwelling older adults: findings from the Health, Aging and Body Composition Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(2):243–250. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02127.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miller M, Stürmer T, Azrael D, Levin R, Solomon DH. Opioid Analgesics and the Risk of Fractures in Older Adults with Arthritis. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(3):430–438. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03318.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jones CM, Mack KA, Paulozzi LJ. Pharmaceutical overdose deaths, United States, 2010. JAMA. 2013;309(7):657–659. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kunik ME, Roundy K, Veazey C, et al. Surprisingly high prevalence of anxiety and depression in chronic breathing disorders. Chest. 2005;127(4):1205–1211. doi: 10.1378/chest.127.4.1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ekström MP, Bornefalk-Hermansson A, Abernethy AP, Currow DC. Safety of benzodiazepines and opioids in very severe respiratory disease: national prospective study. BMJ. 2014;348:g445. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Egan M, Moride Y, Wolfson C, Monette J. Long-term continuous use of benzodiazepines by older adults in Quebec: prevalence, incidence and risk factors. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48(7):811–816. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb04758.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tannenbaum C, Martin P, Tamblyn R, Benedetti A, Ahmed S. Reduction of Inappropriate Benzodiazepine Prescriptions Among Older Adults Through Direct Patient Education. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(6):890–898. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bishop TF, Press MJ, Keyhani S, Pincus HA. Acceptance of insurance by psychiatrists and the implications for access to mental health care. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(2):176–181. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.2862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.