Abstract

Background:

British Columbia undertook a colorectal cancer screening pilot program in 3 communities. Our objective was to assess the performance of 2-specimen fecal immunochemical testing in the detection of colorectal neoplasms in this population-based screening program.

Methods:

A prospective cohort of asymptomatic, average-risk people aged 50 to 74 years completed 2 quantitative fecal immunochemical tests every 2 years, with follow-up colonoscopy if the result of either test was positive. Participant demographics, fecal immunochemical test results, colonoscopy quality indicators and pathology results were recorded. Non-screen-detected colorectal cancer that developed in program participants was identified through review of data from the BC Cancer Registry.

Results:

A total of 16 234 people completed a first round of fecal immunochemical testing, with a positivity rate of 8.6%; 5378 (86.0% of eligible participants) completed a second round before the end of the pilot program, with a positivity rate of 6.7%. Of the 1756 who had a positive test result, 1555 (88.6%) underwent colonoscopy. The detection rate of colorectal cancer was 3.5 per 1000 participants. The positive predictive value of the fecal immunochemical test was 4.9% (95% confidence interval [CI] 3.8%-6.0%) for colorectal cancer, 35.0% (95% CI 32.5%-37.2%) for high-risk polyps and 62.0% (95% CI 59.6%-64.4%) for all neoplasms. The number needed to screen was 283 to detect 1 cancer, 40 to detect 1 high-risk polyp and 22 to detect any neoplasm.

Interpretation:

Screening every 2 years with a 2-specimen fecal immunochemical test surpassed the current benchmark for colorectal cancer detection in population-based screening. This study has implications for other jurisdictions planning colorectal cancer screening programs.

Colorectal cancer is the second most commonly diagnosed type of cancer among Canadian men and the third among Canadian women.1 It is also the second most common cause of death from cancer among men and the third among women in Canada.1 Randomized controlled trials have shown that screening with the guaiac fecal occult blood test can decrease colorectal cancer incidence2 and mortality.3 Analyses have shown that screening of average-risk individuals for colorectal cancer is cost-effective at conventional levels of third-party payers' willingness to pay.4 The Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care has recommended that screening be offered to people 50-74 years of age using a fecal occult blood test every 2 years, preferably through an organized screening program.5

The fecal immunochemical test is an immunologic test consisting of monoclonal or polyclonal antibodies directed against human globin. It is more sensitive and specific than the guaiac fecal occult blood test, and participation rates are higher for the fecal immunochemical test than for the guaiac fecal occult blood test,6 flexible sigmoidoscopy7 or colonoscopy.8 The fecal immunochemical test is the primary screening test for 7 of the Canadian provincial colorectal cancer screening programs: British Columbia (which started in 2013), Alberta (2013), Saskatchewan (2009), Nova Scotia (2009), Prince Edward Island (2011), New Brunswick (2015) and Newfoundland and Labrador (2011). It will also be used in the colorectal cancer screening program to be launched in Quebec.

From January 2009 to April 2013, the BC Cancer Agency oversaw a pilot program, called Colon Check, in 3 communities in which people were offered colorectal cancer screening with a quantitative 2-specimen fecal immunochemical test every 2 years. Our objective was to evaluate the performance of this test in the detection of colorectal cancer and precancerous polyps in this population-based screening program.

Methods

Setting

Three BC communities participated in the Colon Check pilot program: Penticton from January 2009, Powell River from October 2009 and parts of downtown Vancouver from April 2010. The last date of screening through the program was Mar. 31, 2013. These communities were chosen because they represented a mix of rural and urban centres and because of their willingness to participate.

Participants

People were eligible for the pilot program if they were aged 50-74 years, were not experiencing symptoms of colorectal cancer, and resided in one of the communities in the program or their primary care provider worked in one of those locations. People were excluded from the program if they were experiencing rectal bleeding, had a personal history of colorectal cancer, had a personal history of inflammatory bowel disease or had undergone a colonoscopy or sigmoidoscopy within the last 5 years.

The BC Ministry of Health supplied BC Cancer Agency staff with mailing address and date of birth information for citizens of the province from the BC Medical Services Plan database. Potential participants were recruited by personalized mailed invitations using this information, by family doctors and through local publicity. Interested people called the BC Cancer Agency to register for the program, and agency staff enrolled them after confirming their eligibility. People with one or more first-degree relatives with colorectal cancer were identified at the time of registration and their results will be reported separately.9

Design

The primary screening test was a semi-automated fecal immunochemical test (OC-Auto Micro 80; Polymedco Inc.). Participants received 2 fecal immunochemical test kits in the mail and were instructed to take 1 sample from a bowel movement for the first kit and then 1 sample from the next bowel movement for the second kit. Once they had completed the kits, participants returned them to a local laboratory for transport to the Provincial Health Services Central Processing and Receiving Laboratory in Vancouver for analysis.

If both samples were normal, the participant was recalled by Colon Check in 2 years. If both samples were unsatisfactory (because of leakage of the liquid buffer within the specimen container, for instance), the participant was asked to repeat the fecal immunochemical test. Participants for whom 1 sample was unsatisfactory and the other sample was normal were also asked to repeat the test. The screening result was considered abnormal if the amount of hemoglobin in either sample was at least 100 ng/mL buffer (20 μg/g feces). This cut-off was recommended by the test manufacturer. If the result was abnormal, the participant was assessed by a trained nurse navigator and was scheduled for colonoscopy, which is the recommended follow-up examination for a positive fecal immunochemical test result.10

In the precolonoscopy assessment, the nurse navigator evaluated the patient for medical fitness, provided patient education and relayed bowel preparation instructions. Colonoscopy was performed by community colonoscopists, including gastroenterologists, general surgeons and an internal medicine specialist with additional training in colonoscopy. All colonoscopists participated in colonoscopy quality initiatives that were part of the Colon Check program. A standard reporting form was used to collect data on colonoscopy quality indicators, polyp morphology and mode of polypectomy. Tissue specimens were assessed by BC Cancer Agency pathologists, and results were reported in a standardized format.

High-risk precancerous polyps were defined as those polyps requiring a repeat colonoscopy in 3 years, according to published guidelines11 available during the Colon Check pilot program: tubular adenomas 10 mm or greater in size, tubulovillous or villous adenomas, adenomas with high-grade dysplasia, sessile serrated adenomas, traditional serrated adenomas, and multiple (≥ 3) tubular adenomas less than 10 mm in size. Low-risk precancerous polyps were defined as those requiring a repeat colonoscopy in 5 years: 1 or 2 tubular adenomas less than 10 mm in size. For participants with more than 1 neoplasm identified at colonoscopy, the pathology results were classified by the most serious lesion. Non-screen-detected colorectal cancer was defined as cancer diagnosed in the time interval between the date of the participant's last screening test and the date they were due for their next screening test plus 6 months.

The colonoscopy and pathology results were communicated to the participant's family physician, the colonoscopist, the nurse navigator and Colon Check. The nurse navigator conducted a telephone interview with the participant 2 to 4 weeks after the colonoscopy to assess for delayed adverse events and to inform him or her of the pathology results and the date when the participant should next undergo fecal immunochemical testing or colonoscopy. Participants in whom a neoplastic lesion was detected at colonoscopy were recalled for colonoscopy in 5 years for low-risk polyps and 3 years for high-risk polyps. If colorectal cancer or inflammatory bowel disease was identified at colonoscopy, the participant was discharged from Colon Check for ongoing management by their colonoscopist. Participants with a positive fecal immunochemical test result and a negative colonoscopy result were recalled for fecal immunochemical testing in 2 years. All adverse events were reviewed by Colon Check's quality management committee and classified as serious or not serious and as probably related, possibly related or unlikely to be related to the colonoscopy. A serious adverse event was defined as one resulting in a repeat colonoscopy, surgery, hospital admission or death.

The primary outcomes of the study were the detection rate of colorectal neoplasms with the fecal immunochemical test and the positive predictive value (PPV) of this test for colorectal neoplasms. Secondary outcomes were the stage distribution of screen-detected and non-screen-detected colorectal cancers in Colon Check participants and of colorectal cancers in the general BC population.

Data sources

Data on participant demographics, fecal immunochemical test results, colonoscopy results, pathology results and adverse events were collected prospectively from participants, colonoscopists and pathologists and entered into a central database at the BC Cancer Agency. There is mandatory reporting of all cancers diagnosed in BC to the BC Cancer Registry; the registry was reviewed on June 9, 2015, to determine whether Colon Check participants had developed non-screen-detected colorectal cancer.

Statistical analysis

We calculated the PPV for colorectal cancer as the number of participants with an abnormal fecal immunochemical test result who underwent colonoscopy and who had the highest risk pathology finding (i.e., the number of participants with an abnormal fecal immunochemical test result who were subsequently diagnosed with colorectal cancer by colonoscopy) divided by the total number of participants with an abnormal fecal immunochemical test result who underwent colonoscopy.

Ethics approval

We obtained approval from the BC Cancer Agency Research Ethics Board to publish Colon Check data in this report.

Results

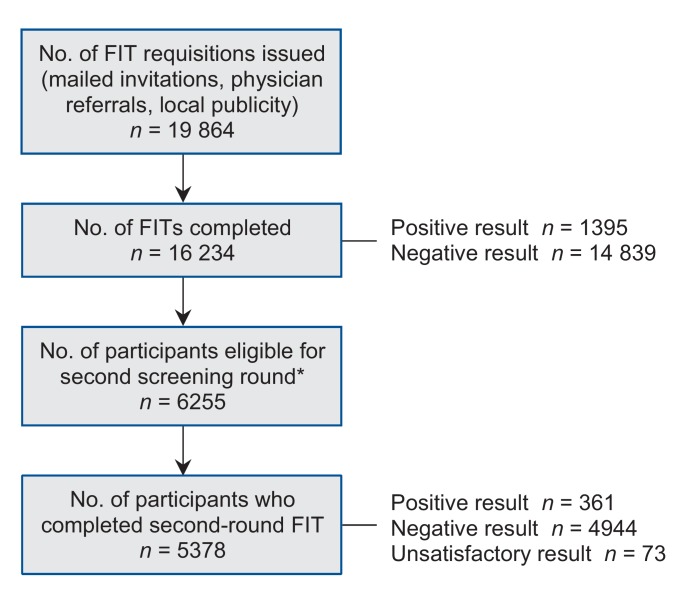

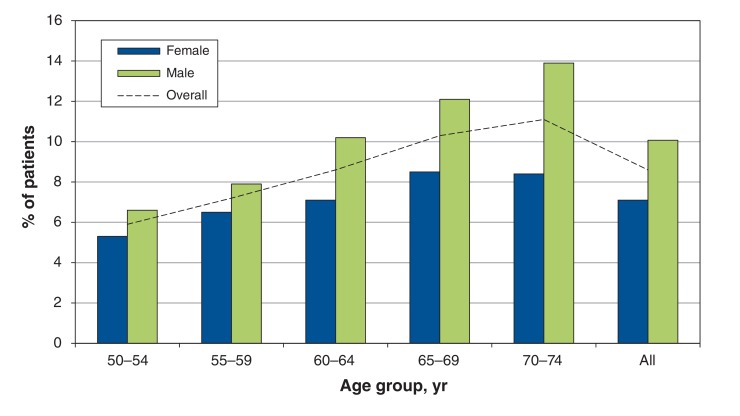

A total of 16 234 people successfully completed a first round of screening with the fecal immunochemical test (Figure 1). The test was deemed unsatisfactory for analysis in 1.3% of participants, primarily because of leakage of the liquid buffer within the specimen container for both samples. The mean age of the screening participants was 62 years (standard deviation 7 yr), and 50.5% were women. Participant characteristics are shown in Table 1. The fecal immunochemical test result was positive in 1395 participants (8.6%). The positivity rate increased with increasing age and was higher among men than among women (Figure 2). Of the 6255 participants who underwent a first round of screening before Apr. 1, 2011, and were eligible to complete a second round of screening before the end of the Colon Check pilot program, 5378 (86.0%) completed the second round. The positivity rate for the second round of screening was 6.7% (n = 361).

Figure 1.

Participation in Colon Check. FIT = fecal immunochemical test. *Participants were eligible for a second screening round if 2 years had passed since their first round of screening and they were less than 75 years of age.

Table 1: Baseline characteristics of Colon Check participants.

| Characteristic | Penticton (start date January 2009) | Powell River(start date October 2009) | Downtown Vancouver (start date April 2010) | Other* | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. (%) of participants | 6732 (41.5) | 3026 (18.6) | 4266 (26.3) | 2210 (13.6) | 16 234 |

| Age, yr, mean ± SD | 61.8 ± 6.8 | 61.1 ± 6.6 | 63.5 ± 6.0 | 60 ± 6.6 | 62.0 ± 6.6 |

| Sex, % | |||||

| Male | 45.2 | 47.7 | 54.9 | 54.3 | 49.5 |

| Female | 54.8 | 52.3 | 45.1 | 45.7 | 50.5 |

Note: SD = standard deviation.

*Participants who lived outside the participating communities but were referred by a primary care physician working in one of those communities.

Figure 2.

Distribution of positivity rates for fecal immunochemical test, by age and sex.

Of the 1756 participants with a positive fecal immunochemical test result for either the first or second round of screening, 1555 (88.6%) underwent 1 or more colonoscopies (1597 colonoscopies were performed in total). The overall cecal intubation rate was 95.9% (95% confidence interval [CI] 95.0%-96.9%), and the overall adequacy of bowel preparation was 97.4% (95% CI 96.6%-98.1%). Of the 1597 colonoscopies performed, 16 (1.0%) resulted in a serious adverse event probably or possibly related to the procedure. There were 3 (0.2%) colon perforations (1 immediate and 2 delayed) and 6 (0.4%) post-polypectomy hemorrhages. There were no deaths in the 30 days after colonoscopy.

At least 1 specimen was submitted to pathology for 1156 (72.4%) of the colonoscopies; 2855 specimens were submitted in total. There were 2040 colorectal neoplasms detected in the 1555 participants who underwent colonoscopy, including 76 colorectal adenocarcinomas. The PPV of the fecal immunochemical test for colorectal cancer, high-risk precancerous polyps, low-risk precancerous polyps and any neoplasm was 4.9% (95% CI 3.8%-6.0%), 35.0% (95% CI 32.5%-37.2%), 22.2% (95% CI 20.1%-24.3%), and 62.0% (95% CI 59.6%-64.4%).

The pathology results are shown in Table 2. For participants with more than 1 neoplasm removed, only the most serious lesion was included. The number needed to screen with the fecal immunochemical test was 283 to detect 1 colorectal cancer (in other words, the detection rate was 3.5 per 1000 participants). The number needed to screen with this test was 40 to detect 1 high-risk polyp and 22 to detect any neoplasm. The number needed to colonoscope was 21 to detect 1 colorectal cancer, 3 to detect 1 high-risk polyp and 2 to detect any neoplastic lesion among people with a positive fecal immunochemical test result.

Table 2: Pathology results for the 1555 participants who underwent colonoscopy after a positive fecal immunochemical test result.

| Pathology result* | No. of cases | Positive predictive value, % (95% CI) | Detection rate per 1000 screened |

|---|---|---|---|

| Colorectal cancer | 76 | 4.9 (3.8-6.0) | 3.5 |

| Precancerous polyp† | 888 | 57.0 (54.7-59.6) | 41.2 |

| High-risk polyp | 543 | 35.0 (32.5-37.2) | 25.2 |

| Low-risk polyp | 345 | 22.2 (20.1-24.3) | 16.0 |

| Any neoplasm | 964 | 62.0 (59.6-64.4) | 44.8 |

Note: CI = confidence interval.

*Pathology results were classified by the most serious lesion identified in each participant.

†This row contains the combined results for high-risk and low-risk precancerous polyps. High-risk precancerous polyps were defined according to published guidelines10 as tubular adenomas ≥ 10 mm in size, tubulovillous or villous adenomas, adenomas with high-grade dysplasia, sessile serrated adenomas, traditional serrated adenomas, and multiple (≥ 3) tubular adenomas less than 10 mm in size. Low-risk precancerous polyps were defined as 1 or 2 tubular adenomas less than 10 mm in size.

The median time from the date of the last screening episode (fecal immunochemical test or colonoscopy) to the follow-up date was 47 (range 23-76) months. Nine non-screen-detected colorectal cancers were identified in Colon Check participants, for a detection rate of 0.55 per 1000 screened. One patient had cancer diagnosed at the site of a previous polypectomy of a high-risk polyp 2 months before a scheduled colonoscopy for surveillance. The remaining 8 participants had had negative fecal immunochemical test results within the 30 months preceding their cancer diagnosis. The median fecal immunochemical test value of the 18 fecal immunochemical tests performed in the 9 participants with non-screen-detected cancer was 8.5 (range 0-71) ng/mL buffer. Two patients had stage I cancer, 2 had stage II, 3 had stage III and 2 had stage IV, classified using the TMN cancer staging system.

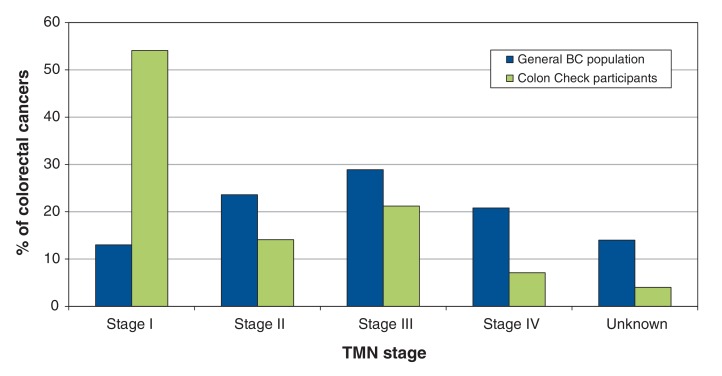

Figure 3 shows the stage distribution of the screen-detected and non-screen-detected colorectal cancers in Colon Check participants and of colorectal cancers in the general BC population. During the period when the Colon Check pilot program was in operation, 36.1% of the colorectal cancers diagnosed in the general BC population were stage I or II, as compared with 68% of those diagnosed in Colon Check participants.

Figure 3.

: Distribution of colorectal cancers diagnosed in Colon Check participants and in the general BC population, classified by the TMN cancer staging system.

Interpretation

We assessed the performance of a 2-specimen quantitative fecal immunochemical test with a cut-off of 100 ng/mL in the detection of colorectal neoplasms. The detection rate for colorectal cancer surpassed the national benchmark of 2 per 1000 screened established through expert consensus by the Canadian Partnership Against Cancer, and the PPV of the fecal immunochemical test for the detection of precancerous polyps was 7% higher than the Partnership's benchmark.12

There was a difference in the distribution of colorectal cancer stages between the general BC population and Colon Check participants. The high rate of localized colorectal cancer among cases identified through the Colon Check program is in keeping with data from other Canadian provincial screening programs13 and should translate into a future decrease in colorectal cancer mortality now that a full screening program has been implemented in BC. According to the results of the 2012 Canadian Community Health Survey, an estimated 45.0% of British Columbians were up to date with colorectal cancer screening.14

Results from 5 of the Canadian provincial colorectal cancer screening programs (including preliminary Colon Check data) showed an adenoma detection rate of 16.9 per 1000 screened and a colorectal cancer detection rate of 1.8 per 1000 screened.13 That these rates were lower than those for the Colon Check program can be explained by the fact that certain provinces use different fecal tests, some of which have a lower sensitivity. The Tuscan screening program in Italy reported a detection rate of 4.5 colorectal cancers per 1000 screened with a fecal immunochemical test.15

In the Colon Check program, the manufacturer's recommended cut-off of 100 ng/mL buffer was used for the fecal immunochemical test; however, a jurisdiction may choose a different cut-off for positivity, which will alter the sensitivity of the test. For instance, the screening program in France uses 2 specimens per screening round with the same brand of fecal immunochemical test as Colon Check but sets a higher cut-off of 150 ng/mL buffer.16 As expected, the positivity rate in the French program (4%) was lower than that in Colon Check and the PPV for colorectal cancer was higher (6.2%). The numbers needed to screen and to colonoscope to detect 1 colorectal cancer were also higher in the French program (450 and 16, respectively). The rate at which non-screen-detected colorectal cancers were discovered in Colon Check participants was similar to the rate in the Tuscan screening program (0.54 per 1000 screened).15

Another positive outcome observed in Colon Check was the low proportion of unsatisfactory fecal immunochemical tests. The high rate of participant compliance with follow-up colonoscopy after a positive fecal immunochemical test result compares favourably with that of other programs. We attribute this finding in part to the patient navigation incorporated into Colon Check. We did not perform an economic analysis; however, the goal of patient navigation was to replace a physician consultation and thereby to save the associated physician fee. The provision of additional colonoscopy resources specifically for Colon Check participants meant that the participants could avoid the usual colonoscopy wait times; we believe this contributed to the high rate of follow-up colonoscopy.

Limitations

We were unable to accurately determine the rate of participation in Colon Check because people who lived outside of the target communities were eligible to participate if their primary care provider practised within one of the communities. Although these communities collectively demonstrate diversity in age, sex, ethnicity and socioeconomic status and thus we believe the Colon Check results should be generalizable to the BC population as a whole, we did not formally assess demographics. In addition, because people with a negative fecal immunochemical test result did not undergo colonoscopy, we were unable to determine the test's true-negative and false-negative rates.

Conclusion

Programmatic colorectal cancer screening of average-risk British Columbians with fecal immunochemical testing every 2 years resulted in a colorectal cancer detection rate of about 1 in 300, with a favourable shift in colorectal cancer stage compared with colorectal cancers diagnosed in the general BC population. The participants of Colon Check will continue to be eligible for colorectal cancer screening in the BC Colon Screening Program, which was launched across the province on Nov. 15, 2013. Long-term monitoring is ongoing to assess the effect of population-based screening on colorectal cancer incidence and mortality in BC.

Supplemental information

For reviewer comments and the original submission of this manuscript, please see www.cmajopen.ca/content/4/4/E668/suppl/DC1

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Advisory Committee on Cancer Statistics. Canadian cancer statistics 2015. Toronto: Canadian Cancer Society; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mandel JS, Church TR, Bond JH, et al. The effect of fecal occult-blood screening on the incidence of colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1603–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200011303432203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hewitson P, Glasziou P, Watson E, et al. Cochrane systematic review of colorectal cancer screening using the fecal occult blood test (hemoccult): an update. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:1541–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.01875.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Telford JJ, Levy AR, Sambrook JC, et al. The cost-effectiveness of screening for colorectal cancer. CMAJ. 2010;182:1307–13. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care. Recommendations on screening for colorectal cancer in primary care. CMAJ. 2016;188:340–8. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.151125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Rossum LG, van Rijn AF, Laheij RJ, et al. Random comparison of guaiac and immunochemical fecal occult blood tests for colorectal cancer in a screening population. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:82–90. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.03.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hol L, van Leerdam ME, van Ballegooijen M, et al. Screening for colorectal cancer: randomised trial comparing guaiac-based and immunochemical faecal occult blood testing and flexible sigmoidoscopy. Gut. 2010;59:62–8. doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.177089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Quintero E, Castells A, Bujanda L, et al. Colonoscopy versus fecal immunochemical testing in colorectal-cancer screening. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:697–706. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1108895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moosavi S, Gentile L, Gondara L, et al. Su1038 performance of fecal immunochemical test (FIT) in patients with a family history of colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:S452. doi: 10.1093/jcag/gwz027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Winawer S, Fletcher R, Rex D, et al. Colorectal cancer screening and surveillance: clinical guidelines and rationale. Update based on new evidence. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:544–60. doi: 10.1053/gast.2003.50044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lieberman DA, Rex DK, Winawer SJ, et al. Guidelines for colonoscopy surveillance after screening and polypectomy: a consensus update by the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:844–57. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Quality determinants and indicators for measuring colorectal cancer screening program performance in Canada. Toronto: Canadian Partnership Against Cancer; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Major D, Bryant H, Delaney M, et al. Colorectal cancer screening in Canada: results from the first round of screening for five provincial programs. Curr Oncol. 2013;20:252–7. doi: 10.3747/co.20.1646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.The 2016 cancer system performance report. Toronto: Canadian Partnership Against Cancer; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zappa M, Castiglione G, Paci E, et al. Measuring interval cancers in population-based screening using different assays of fecal occult blood testing: the district of Florence experience. Int J Cancer. 2001;92:151–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Raginel T, Puvinel J, Ferrand O, et al. A population-based comparison of immunochemical fecal occult blood tests for colorectal cancer screening. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:918–25. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.01.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.