Abstract

Background:

In Canada, interferon-free, direct-acting antiviral hepatitis C virus (HCV) regimens are costly. This presents challenges for universal drug coverage of the estimated 220 000 people with chronic HCV infection nationwide. The study objective was to appraise criteria for reimbursement of 4 HCV direct-acting antivirals in Canada.

Methods:

We reviewed the reimbursement criteria for simeprevir, sofosbuvir, ledipasvir-sofosbuvir and paritaprevir-ritonavir-ombitasvir plus dasabuvir in the 10 provinces and 3 territories. Data were extracted from April 2015 to June 2016. The primary outcomes extracted from health ministerial websites were: 1) minimum fibrosis stage required, 2) drug and alcohol use restrictions, 3) HIV coinfection restrictions and 4) prescriber type restrictions.

Results:

Overall, 85%-92% of provinces/territories limited access to patients with moderate fibrosis (Meta-Analysis of Histologic Data in Viral Hepatitis stage F2 or greater, or equivalent). There were no drug and alcohol use restrictions; however, several criteria (e.g., active injection drug use) were left to the discretion of the physician. Quebec did not reimburse simeprevir and sofosbuvir for people coinfected with HIV; no restrictions were found in the remaining jurisdictions. Prescriber type was restricted to specialists in up to 42% of provinces/territories.

Interpretation:

This review of criteria of reimbursement of HCV direct-acting antivirals in Canada showed substantial interjurisdictional heterogeneity. The findings could inform health policy and support the development and adoption of a national HCV strategy.

In Canada, an estimated 220 000 people have chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection.1 It is estimated that, by 2035, cirrhosis will develop in nearly one-quarter of Canadians with chronic HCV infection, with total associated health care costs per annum rising from about $161 million in 2013 to about $258 million by 2032.2

Interferon-free, direct-acting antiviral HCV regimens achieve sustained virologic response rates above 90% even in patients with compensated cirrhosis.3-10 Sustained virologic response is associated with lowered risk of liver transplantation, liver-related mortality and all-cause mortality11,12 and improved quality-of-life outcomes.13,14 Shorter therapy duration and fewer adverse events have further reduced patient-level barriers to care.15-18 However, given that the list price for HCV direct-acting antivirals in Canada is about $60 000 for a 12-week course, funding all those chronically infected with HCV presents challenges.

A study of sofosbuvir reimbursement criteria in the United States identified considerable variability across state fee-for-service Medicaid plans.19 Three-quarters of the 42 states with data requested evidence of advanced fibrosis (Meta-Analysis of Histologic Data in Viral Hepatitis stage F3) or cirrhosis (stage F4). Furthermore, most states (88%) had restrictions on drug and alcohol use, with half requiring abstinence before the start of treatment. In one-quarter of the states, populations coinfected with HIV had to be treated with antiretroviral therapy or show suppressed HIV viral loads. Furthermore, one-third of the states limited prescriber type to specialists. These restrictions do not align with published and accepted clinical guidelines.20-22 Additional research into Medicaid-managed care programs, federal and state corrections plans, private plans and other payer sources would provide greater context to therapy access in the US.

In contrast to the multitiered, privately financed health care system in the US, Canada has a publicly funded national health insurance program that provides coverage to each resident. Although Canada's 10 provinces and 3 territories are collectively governed by the Canada Health Act, every jurisdiction administers its own health plan. Since 2010, the pan-Canadian Pharmaceutical Alliance, made up of provincial/territorial health minister representatives, has negotiated drug prices with manufacturers.23 In February 2016, the federal government joined the alliance.23,24 For these reasons, it was hypothesized that Canada would have greater reimbursement consistency by jurisdiction than the US.

The aim of this study was to appraise reimbursement criteria in Canada for simeprevir, sofosbuvir, ledipasvir-sofosbuvir and paritaprevir-ritonavir-ombitasvir plus dasabuvir. We also reviewed the criteria for Aboriginal people and federal prisoners as these populations are disproportionately affected by HCV infection25-28 and receive drug coverage from national plans.

Methods

Data sources

We collected reimbursement criteria for simeprevir (with peginterferon plus ribavirin), sofosbuvir (with peginterferon and/or ribavirin), ledipasvir-sofosbuvir and paritaprevir-ritonavir-ombitasvir plus dasabuvir (with or without ribavirin) for all provinces and territories as well as the national Non-Insured Health Benefits Program and the Correctional Service Canada drug plans (n = 15). Because each provincial/territorial health ministry sets its own reimbursement criteria, information was primarily collected from jurisdiction websites, with national plan information collected from federal websites (Table 1).

Table 1: Provincial/territorial and federal health ministries in Canada.

| Jurisdiction | Health ministry | Website |

|---|---|---|

| Province/territory | ||

| British Columbia | British Columbia Ministry of Health | www.gov.bc.ca/health |

| Alberta | Alberta Health | www.health.alberta.ca |

| Saskatchewan | Saskatchewan Ministry of Health | www.saskatchewan.ca/government/government-structure/ministries/health |

| Manitoba | Manitoba Health | www.gov.mb.ca/health |

| Ontario | Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care | www.health.gov.on.ca |

| Quebec | Quebec Ministry of Health and Social Services | www.msss.gouv.qc.ca |

| New Brunswick | New Brunswick Department of Health | www2.gnb.ca/content/gnb/en/departments/health.html |

| Nova Scotia | Nova Scotia Department of Health and Wellness | http://novascotia.ca/DHW |

| Prince Edward Island | Prince Edward Island Department of Health and Wellness | www.gov.pe.ca/health |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | Newfoundland and Labrador Department of Health and Community Services | www.health.gov.nl.ca/health |

| Yukon Territory | Yukon Health and Social Services | www.hss.gov.yk.ca |

| Northwest Territories | Northwest Territories Health and Social Services | www.hss.gov.nt.ca |

| Nunavut | Nunavut Department of Health | www.gov.nu.ca/health |

| National | ||

| Non-Insured Health Benefits Program* | Health Canada | www.hc-sc.gc.ca |

| Correctional Service Canada formulary† | Correctional Service Canada | www.csc-scc.gc.ca |

*Federally funded public drug benefit program for First Nations people and Inuit.

†Federally funded public drug benefit program for federal prisoners (sentences ≥ 2 yr).

We extracted data including special authorization request forms, drug formularies, amendments to formularies and drug benefit lists from publicly available online reimbursement information. If desired information was not available online, we contacted the ministry directly. Coauthors who were health care practitioners also facilitated access to documentation. When information could not be retrieved or was not available (e.g., the therapy was not reimbursed), data were labelled "NA" (i.e., not available). If a restriction (e.g., drug and alcohol use) was not listed with the criteria, data were labelled as "none listed;" this does not necessarily indicate that no restriction exists but, rather, that a written instruction could not be identified.

We obtained restriction information for First Nations people and Inuit from the Non-Insured Health Benefits Program, which reimburses the cost of medications and medical services not covered under provincial/territorial or private plans for these populations. We obtained restriction criteria for prisoners in federal penitentiaries (sentences ≥ 2 yr) from Correctional Service Canada. (Reimbursement for prisoners with sentences of less than 2 years follows criteria set by the province or territory where the sentence is being served, and we did not review this information.)

Data extraction took place from Apr. 22, 2015, to June 21, 2016. Information was collected by 2 of the authors (A.D.M. and S.S.), who cross-checked each other's data; inconsistencies were resolved through consensus. We organized the data using Microsoft Excel.

Primary outcomes

Primary outcomes were based on a previous study of Medicaid reimbursement in the US19 and included: 1) minimum fibrosis stage required, 2) drug and alcohol use restrictions, 3) HIV coinfection restrictions and 4) prescriber type restrictions. We organized the data into categories so that criteria could be compared across provinces/territories. We categorized fibrosis data as the minimum fibrosis stage required (categories: no restrictions, ≥ F2, ≥ F3 or F4 of the Meta-Analysis of Histologic Data in Viral Hepatitis scoring system or equivalent). Depending on the jurisdiction, fibrosis stage was assessed by means of transient elastography (e.g., FibroScan), aspartate aminotransferase-to-platelet ratio index score, fibrosis-4 index score or liver biopsy. We categorized drug and alcohol use criteria based on restrictions on current/past drug or alcohol use (categories: yes, no). HIV coinfection data were categorized as to whether people coinfected with HIV were eligible for treatment (categories: eligible [those with HIV coinfection had the same criteria as those with HCV infection only], ineligible [HIV coinfection was listed in the exclusion criteria]). Prescriber data were categorized as whether a hepatologist, gastroenterologist or infectious disease specialist prescriber was required or nonspecialist options were permitted (categories: specialist, general practitioner). In cases in which a physician with experience treating patients with HCV infection could prescribe treatment once he or she met designated prescriber status as defined by the jurisdiction, this was categorized as "general practitioner." We also noted treatment eligibility for decompensated cirrhosis (categories: eligible, ineligible, may be considered). We defined decompensated cirrhosis as Child-Pugh score greater than 6 (class B or C).19

Statistical analysis

We used descriptive statistics to show the proportion of provinces/territories that restrict drug coverage by primary outcome. Map images were created with Tableau Software version 9.0.

Results

Provinces/territories

Simeprevir with peginterferon plus ribavirin

Simeprevir was approved for use in HCV genotype 1 infection in combination with peginterferon plus ribavirin. Patients with genotype 1a infection required resistance testing showing absence of NS3 polymorphism Q80K.

Prince Edward Island did not reimburse simeprevir. Eleven (92%) of the 12 other jurisdictions required a fibrosis stage of F2 or greater (Table 2); Quebec did not provide this information (Appendix 1, available at www.cmajopen.ca/content/4/4/E605/suppl/DC1). No drug and alcohol use criteria were listed. In 2 jurisdictions (17%) (Manitoba and Ontario), people coinfected with HIV were eligible for treatment with the same criteria as for HCV monoinfection. This population was ineligible for treatment in Quebec; however, coauthors who were health care practitioners in that province specified that exceptions could be granted via the "patient d'exception" (exception patient) measure, whereby a prescriber provides additional justification for treatment. Five provinces/territories (42%) required specialist prescribing, and 3 jurisdictions (25%) allowed general practitioners to prescribe. Seven jurisdictions (58%) prohibited treatment for patients with decompensated cirrhosis.

Table 2: Key eligibility criteria for reimbursement of simeprevir with peginterferon plus ribavirin for treatment of hepatitis C virus infection, by jurisdiction.

| Jurisdiction | Restriction | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minimum fibrosis stage required | Substance use | HIV coinfection | Prescriber | Decompensated cirrhosis | |

| Province/territory | |||||

| British Columbia | F2 | None listed | None listed | General practitioner | None listed |

| Alberta | F2 | None listed | None listed | None listed | Ineligible |

| Saskatchewan | F2 | None listed | None listed | General practitioner | None listed |

| Manitoba | F2 | None listed | Eligible | Specialist | Ineligible |

| Ontario | F2 | None listed | Eligible | General practitioner | Ineligible |

| Quebec | None listed* | None listed | Ineligible† | None listed | None listed |

| New Brunswick | F2 | None listed | None listed | None listed | Ineligible |

| Nova Scotia | F2 | None listed | None listed | Specialist‡ | Ineligible |

| Prince Edward Island | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | F2 | None listed | None listed | None listed | Ineligible |

| Yukon | F2 | None listed | None listed | Specialist | Ineligible |

| Northwest Territories | F2 | None listed | None listed | Specialist‡ | None listed |

| Nunavut | F2 | None listed | None listed | Specialist‡ | None listed |

| Federal | |||||

| Non-Insured Health Benefits Program | F2 | None listed | None listed | Specialist‡ | None listed |

| Correctional Service Canada | F2§ | None listed¶ | None listed | None listed | None listed |

Note: NA = not available.

*However, coauthors indicated that in practice there were no fibrosis stage restrictions.

†However, exceptions could be granted via the "patient d'exception" (exception patient) measure.

‡None listed in criteria; however, a specialist prescription was required for peginterferon-based treatments.

§Treatment prioritized to patients with stage F3 or F4 fibrosis; treatment for those with stage F0, F1 or F2 fibrosis was reviewed on a case-by-case basis.

¶Directly observed therapy required.

Sofosbuvir with peginterferon and/or ribavirin

Sofosbuvir was approved for use in genotypes 1-3 infections in combination with peginterferon and/or ribavirin. In Quebec, reimbursement for genotype 4 infection was also permitted.

Sofosbuvir was not reimbursed in Prince Edward Island. Eleven provinces/territories (92%) required fibrosis stage F2 or greater (Table 3). Quebec did not list this information (Appendix 2, available at www.cmajopen.ca/content/4/4/E605/suppl/DC1). Coauthors who were health care practitioners in Quebec indicated that there were no known fibrosis stage restrictions. No jurisdiction listed drug and alcohol use restrictions. There were no stated restrictions for HIV-coinfected people in 9 jurisdictions (75%). Those coinfected with HIV were not eligible for treatment in Quebec, although exceptions could be granted through the "patient d'exception" measure. Eight jurisdictions (67%) permitted general practitioners to prescribe, and 3 jurisdictions (25%) required specialist prescribers; Quebec did not list this information. Treatment of decompensated cirrhosis was considered on a case-by-case basis in 8 jurisdictions (67%).

Table 3: Key eligibility criteria for reimbursement of sofosbuvir with peginterferon and/or ribavirin for treatment of hepatitis C virus infection, by jurisdiction.

| Jurisdiction | Restriction | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minimum fibrosis stage required | Substance use | HIV coinfection | Prescriber | Decompensated cirrhosis | |

| Province/territory | |||||

| British Columbia | F2 | None listed* | Eligible | General practitioner | May be considered |

| Alberta | F2 | None listed | Eligible | General practitioner | May be considered |

| Saskatchewan | F2 | None listed† | Eligible | General practitioner | May be considered |

| Manitoba | F2 | None listed | Eligible | Specialist | May be considered |

| Ontario | F2 | None listed | Eligible | General practitioner | May be considered |

| Quebec | None listed‡ | None listed | Ineligible§ | None listed | None listed |

| New Brunswick | F2 | None listed | Eligible | Specialist | May be considered |

| Nova Scotia | ≥ F2 | None listed | Eligible | General practitioner | May be considered¶ |

| Prince Edward Island | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | F2 | None listed | Eligible | General practitioner | None listed |

| Yukon | F2 | None listed | Eligible | Specialist | May be considered |

| Northwest Territories | F2 | None listed | None listed | General practitioner | None listed |

| Nunavut | F2 | None listed | None listed | General practitioner | None listed |

| Federal | |||||

| Non-Insured Health Benefits Program | F2 | None listed | None listed | General practitioner | None listed |

| Correctional Service Canada | F2** | None listed†† | None listed | None listed | None listed |

Note: NA = not available.

*No specific criteria, but exclusion criteria state: "Patients who are at high risk for non-compliance."

†However, prescriber could indicate that directly observed therapy was recommended; also, the patient consented (via signature) to understanding treatment adherence.

‡However, coauthors indicated that in practice there were no fibrosis stage restrictions.

§However, exceptions could be granted via the "patient d'exception" (exception patient) measure.

¶Source: coauthor.

**Treatment prioritized to patients with stage F3 or F4 fibrosis; treatment for those with stage F0, F1 or F2 fibrosis was reviewed on a case-by-case basis.

††Directly observed therapy required.

Ledipasvir-sofosbuvir

Ledipasvir-sofosbuvir was approved for use in HCV genotype 1 infection.

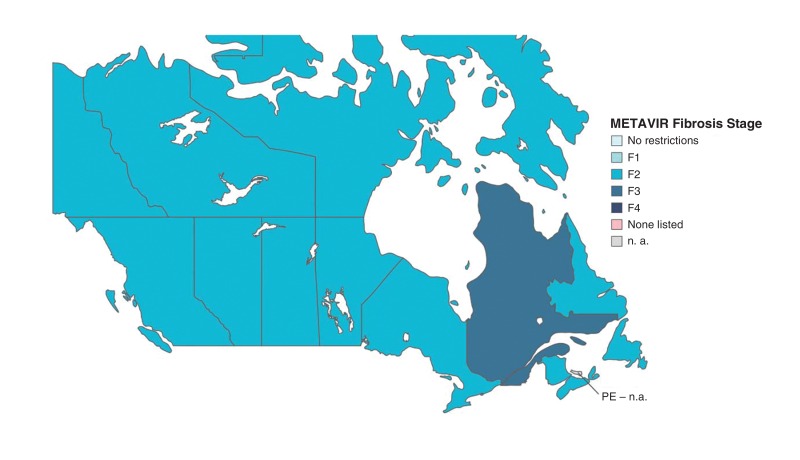

Prince Edward Island did not reimburse this treatment (Figure 1). Eleven provinces/territories (92%) required fibrosis stage F2 of greater (Table 4). In Quebec, fibrosis stage requirements depended on the number of years the treatment had been on the market. In year 1 (July 2015-July 2016), evidence of advanced fibrosis (≥ stage F3) or cirrhosis was required. In years 2-3, patients with moderate (stage F2) or mild (stage F1) fibrosis plus an indicator of poor prognosis such as coinfection with HIV or hepatitis B virus will be required. For years 4-6, all patients will be eligible for treatment regardless of fibrosis stage. There were no drug and alcohol use restrictions. However, in British Columbia, at the prescriber's discretion, "patients who are at high risk for non-compliance" were ineligible, and Saskatchewan provided a directly observed therapy option for prescribers. In all 12 jurisdictions, people coinfected with HIV were eligible for treatment with HCV monoinfection criteria. Nine provinces/territories (75%) allowed general practitioners to prescribe, and 3 jurisdictions (25%) required specialist prescribers. In 8 jurisdictions (67%), patients with decompensated cirrhosis "may be considered" for treatment. Patients with decompensated cirrhosis were eligible for treatment in Quebec.

Figure 1.

Minimum fibrosis stage required for reimbursement of ledipasvir-sofosbuvir for treatment of hepatitis C virus infection in Canadian provinces/territories. METAVIR = Meta-Analysis of Histologic Data in Viral Hepatitis, n. a. = not available.

Table 4: Key eligibility criteria for reimbursement of ledipasvir-sofosbuvir reimbursement for treatment of hepatitis C virus infection, by jurisdiction.

| Jurisdiction | Restriction | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minimum fibrosis stage required | Substance use | HIV coinfection | Prescriber | Decompensated cirrhosis | |

| Province/territory | |||||

| British Columbia | F2 | None listed* | Eligible | General practitioner | May be considered |

| Alberta | F2 | None listed | Eligible | General practitioner | May be considered |

| Saskatchewan | F2 | None listed† | Eligible | General practitioner | May be considered |

| Manitoba | F2 | None listed | Eligible | Specialist | May be considered |

| Ontario | F2 | None listed | Eligible | General practitioner | May be considered |

| Quebec | F3‡ | None listed | Eligible§ | General practitioner | Eligible |

| New Brunswick | F2 | None listed | Eligible | General practitioner | None listed |

| Nova Scotia | F2 | None listed | Eligible | Specialist | May be considered¶ |

| Prince Edward Island | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | F2 | None listed | Eligible | General practitioner | May be considered |

| Yukon | F2 | None listed | Eligible | Specialist | May be considered |

| Northwest Territories | F2 | None listed | Eligible | General practitioner | None listed |

| Nunavut | F2 | None listed | Eligible | General practitioner | None listed |

| Federal | |||||

| Non-Insured Health Benefits Program | F2 | None listed | Eligible | General practitioner | None listed |

| Correctional Service Canada | F2** | None listed†† | Eligible | None listed | None listed |

Note: NA = not available.

*No specific criteria, but exclusion criteria stated: "Patients who are at high risk for non-compliance."

†However, prescriber could indicate that directly observed therapy was recommended; also, the patient consented (via signature) to understanding treatment adherence.

‡In year 1 (2015/16), only those with stage F3 or F4 fibrosis received reimbursement.

§Treated in year 1 if stage F3 or F4 fibrosis.

¶Source: coauthor.

**Treatment prioritized to patients with stage F3 or F4 fibrosis; treatment for those with stage F0, F1 or F2 fibrosis was reviewed on a case-by-case basis.

††Directly observed therapy required.

Paritaprevir-ritonavir-ombitasvir plus dasabuvir (with or without ribavirin)

Paritaprevir-ritonavir-ombitasvir plus dasabuvir (with or without ribavirin) was approved for use in genotypes 1a or 1b subtype infections. Prince Edward Island permitted treatment of genotype 4 infection.

Of the 13 provinces/territories, 11 (85%) required fibrosis stage F2 or greater (Table 5). Fibrosis stage F3 or F4 was required in Quebec in year 1, with increased eligibility in subsequent years (Appendix 3, available at www.cmajopen.ca/content/4/4/E605/suppl/DC1). Prince Edward Island had no fibrosis stage requirements. There were no drug and alcohol use restrictions. At the discretion of the prescriber, Prince Edward Island listed "methadone or equivalent for at least 6 months" and "stable address" in the inclusion criteria and active injection drug use in the exclusion criteria. Eleven jurisdictions (85%) allowed patients coinfected with HIV to receive therapy with HCV monoinfection criteria. Prince Edward Island required those coinfected with HIV to be treated off-island by a specialist. Three jurisdictions (23%) required specialist prescribing, and 8 jurisdictions (62%) permitted prescribing by general practitioners. In 9 jurisdictions (69%), patients with decompensated cirrhosis were ineligible for treatment.

Table 5: Key eligibility criteria for reimbursement of paritaprevir-ritonavir-ombitasvir plus dasabuvir (with or without ribavirin) for treatment of hepatitis C virus infection, by jurisdiction.

| Jurisdiction | Restriction | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minimum fibrosis stage required | Substance use | HIV coinfection | Prescriber | Decompensated cirrhosis | |

| Province/territory | |||||

| British Columbia | F2 | None listed* | Eligible | General practitioner | None listed |

| Alberta | F2 | None listed | Eligible | General practitioner | Ineligible |

| Saskatchewan | F2 | None listed† | Eligible | General practitioner | Ineligible |

| Manitoba | F2 | None listed | Eligible | Specialist | Ineligible |

| Ontario | F2 | None listed | Eligible | General practitioner | Ineligible |

| Quebec | F3‡ | None listed | Eligible§ | General practitioner | Ineligible |

| New Brunswick | F2 | None listed | Eligible | General practitioner | Ineligible |

| Nova Scotia | F2 | None listed | Eligible | Specialist | Ineligible |

| Prince Edward Island | No restrictions | None listed¶ | Eligible** | General practitioner | None listed |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | F2 | None listed | Eligible | General practitioner | Ineligible |

| Yukon | F2 | None listed | Eligible | Specialist | Ineligible |

| Northwest Territories | F2 | None listed | None listed | None listed | None listed |

| Nunavut | F2 | None listed | None listed | None listed | None listed |

| Federal | |||||

| Non-Insured Health Benefits Program | F2 | None listed | None listed | None listed | None listed |

| Correctional Service Canada | F2†† | None listed | None listed | None listed | None listed |

*No specific criteria, but exclusion criteria stated: "Patients who are at high risk for non-compliance."

†However, prescriber could indicate that directly observed therapy was recommended; also, the patient consented (via signature) to understanding treatment adherence.

‡In year 1 (2015/16), only those with stage F3 or F4 fibrosis received reimbursement.

§Treated in year 1 if stage F3 or F4 fibrosis.

¶There were restrictions (e.g., active injection drug use) left to physician's discretion.

**Must be treated by a specialist off-island.

††Treatment prioritized to patients with stage F3 or F4 fibrosis; treatment for those with stage F0, F1 or F2 fibrosis was reviewed on a case-by-case basis.

First Nations people and Inuit and federal prisoners

The Non-Insured Health Benefits Program and Correctional Service Canada criteria required a minimum of stage F2 fibrosis for all treatments (Tables 2-5). Correctional Service Canada criteria stated that directly observed therapy was mandatory, and treatment was prioritized for patients with stage F3 or F4 fibrosis. Non-Insured Health Benefits Program criteria required specialist prescribing for simeprevir. Both national drug plans permitted populations coinfected with HIV to be treated with ledipasvir-sofosbuvir.

Interpretation

We found variability in criteria for reimbursement of HCV direct-acting antivirals by jurisdiction in Canada. Depending on the treatment, 85%-92% of provinces/territories limited reimbursement to patients with fibrosis stage F2 or greater. No alcohol or drug use restrictions were found. Quebec listed HIV coinfection restrictions. Overall, 23%-42% of jurisdictions restricted prescriber type to specialists.

In contrast to Canada, 74% of state fee-for-service Medicaid plans in the US limit reimbursement to patients with evidence of advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis (stage F3 or F4).19 Clinical guidelines state that all patients with chronic HCV infection, irrespective of disease stage, should receive treatment,20-22 including prioritization of treatment for populations at risk of transmitting HCV, e.g., people who inject drugs.22 A review by the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health showed that treating patients across all fibrosis stages is cost-effective.29 Quebec implemented tiered fibrosis staging based on cost-effective analyses, a model that could be followed by other jurisdictions. Furthermore, several US states have removed fibrosis stage restrictions following potential lawsuits from patients.30 Fibrosis stage restrictions should be reviewed in Canada.

Although there were no drug and alcohol use restrictions for HCV direct-acting antiviral therapy in Canada, 50% of US states require drug and/or alcohol abstinence before the start of treatment.19 Considering that treatment of HCV infection for people who inject drugs is safe and effective,31 is cost-effective32,33 and would prevent HCV transmission,34 removal of these restrictions is warranted. HIV coinfection restrictions were mostly nonexistent in Canada, whereas 25% of US states request evidence of antiretroviral therapy or suppressed HIV RNA levels.19 Canada's broader access is more aligned with clinical guidelines.20-22 Up to half of jurisdictions in Canada restricted prescriber type to specialist. Although specialists are better trained to oversee direct-acting antiviral-based therapy in selected circumstances (e.g., decompensated cirrhosis), providing general practitioners with education, training and linkage to HCV specialists could broaden therapy access to regions where specialists are limited (e.g., Prince Edward Island). In Australia, all general practitioners can prescribe HCV therapies in consultation with a specialist (e.g., via email), a practice that could be emulated in Canada.35

Since March 2016, the Australian government has provided universal access to HCV treatments - committing A$1 billion over the next 5 years - with no restrictions based on liver disease stage, recent drug use, HIV coinfection or specialist prescribing.36,37 Although there is a cap on expenditure, there is none on the number of patients treated per year, with 26 000 treated in the first 5 months of listing (12% of 230 000 people with chronic HCV infection).38 The development of a national drug formulary in Canada could allow for greater standardization of treatment reimbursement and perhaps result in greater "buying power" in negotiating prices for new therapies.39

Limitations

There were several study limitations. Retrieving complete online criteria was challenging. Although ministries provided criteria when contacted, greater information transparency is needed. In addition, online criteria may not be up to date; for example, the Non-Insured Health Benefits Program criteria updates lagged behind those of other jurisdictions, which could possibly impede treatment access. Also, criteria may have been updated after the data were extracted. Furthermore, this study cannot address implementation of criteria. Additional research might also highlight greater interjurisdictional heterogeneity, e.g., fibrosis stage cut-off values and methodologies differed by jurisdiction. We were unable to retrieve online private health insurance criteria for comparison. Two US studies investigating fewer than 7 state plans showed that insurance type was associated with initiation of HCV infection treatment and approval of reimbursement claims.40-42 Similar research in Canada would be beneficial.

Implications for practice

This review of criteria for reimbursement of HCV direct-acting antivirals in Canada showed greater reimbursement homogeneity than in the US.19 The purchasing power of the pan-Canadian Pharmaceutical Alliance may partly explain this result, as US states lack an equivalent committee. The alliance process may, however, inadvertently benefit jurisdictions with larger HCV-affected populations (i.e., that purchase more drugs). Prince Edward Island negotiated with a drug manufacturer directly and, as a result, did not offer sofosbuvir and ledipasvir-sofosbuvir.43 The impact of the alliance, especially with the addition of federal plans, will become clearer following further negotiations.44

To achieve World Health Organization HCV elimination targets by 2030,45 increased uptake of HCV therapy, especially by people who inject drugs, is essential to reduce HCV incidence and contribute to viral elimination in Canada. Restrictions such as fibrosis stage are neither cost-effective nor evidence-based. Although a "one-size-fits-all" strategy has drawbacks (e.g., the ability of provinces/territories to respond to HCV burdens will vary), the development and adoption of a national HCV strategy in Canada akin to those in Australia46 and Scotland47,48 could facilitate volume-based discounting, reduce provincial/territorial heterogeneity, direct treatment to at-risk populations and broaden equitable access to enable the elimination of HCV infection in Canada.

Conclusion

This review of criteria for reimbursement of HCV direct-acting antivirals in Canada showed substantial interjurisdictional heterogeneity, with most provinces/territories having restrictions based on liver disease stage, few restrictions based on drug and alcohol use, and allowing prescribing by general practitioners.

Supplemental information

For reviewer comments and the original submission of this manuscript, please see www.cmajopen.ca/content/4/4/E605/suppl/DC1

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Evan Cunningham for his assistance with the maps.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: Jordan Feld has received consulting fees from AbbVie, Abbott, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead Sciences, Merck and Janssen. Marina Klein received research support from Merck, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead Sciences and ViiV Healthcare, consulting fees from ViiV, AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb and Gilead Sciences, and honoraria for lectures from AbbVie and Merck. Jason Grebely is a consultant/advisor for and has received research grants from AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead Sciences, Merck/MSD and Cepheid. Lisa Barrett has received research support from AbbVie and consulting fees from AbbVie, Gilead Sciences, Bristol-Myers Squibb and Merck. Julie Bruneau has received research support from Gilead Sciences and consulting fees from AbbVie, Gilead Sciences and Merck/MSD. Curtis Cooper has received industry support from Abbvie, Gilead Sciences and Merck/MSD. Mel Krajden has received support from Boehringer Ingelheim, Hologic, Merck/MSD, Roche and Siemens. AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead Sciences, Janssen and Merck/MSD had no role in the conception, design, analysis or interpretation of this study and provided no funding in relation to this work.

Funding: The Canadian Network on Hepatitis C (CanHepC) is supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (grant NHC-142832). The study content does not necessarily represent the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and the Public Health Agency of Canada. The Kirby Institute is funded by the Department of Health and Ageing, Australian Government. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent the position of the Australian Government. Alison Marshall holds a University International Postgraduate Award from UNSW Australia and is also supported by the CanHepC Trainee Program. Sahar Saeed holds doctoral training awards from the Fonds de recherche du Québec - Santé and the CanHepC Trainee Program. Curtis Cooper is an Ontario HIV Treatment NetworkResearch Chair. Marina Klein is supported by a Chercheurs nationaux career award from the Fonds de recherche du Québec - Santé and received grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) and the CIHR Canadian HIV Trials Network. Lynn Taylor is supported in part by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) (grant P30AI042853). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIAID or the National Institutes of Health. Jason Grebely was supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council Career Development Fellowship Award (1112352).

References

- 1.Trubnikov M, Yan P, Archibald C. Estimated prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection in Canada, 2011. Can Commun Dis Rep 2014;40-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Myers RP, Krajden M, Bilodeau M, et al. Burden of disease and cost of chronic hepatitis C infection in Canada. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;28:243–50. doi: 10.1155/2014/317623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Afdhal N, Reddy KR, Nelson DR, et al. Ledipasvir and sofosbuvir for previously treated HCV genotype 1 infection. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1483–93. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1316366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Afdhal N, Zeuzem S, Kwo P, et al. ION-1 Investigators. Ledipasvir and sofosbuvir for untreated HCV genotype 1 infection. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1889–98. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1402454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feld JJ, Kowdley KV, Coakley E, et al. Treatment of HCV with ABT-450/r-ombitasvir and dasabuvir with ribavirin. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1594–603. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1315722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lawitz E, Mangia A, Wyles D, et al. Sofosbuvir for previously untreated chronic hepatitis C infection. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1878–87. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1214853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lawitz E, Poordad F, Brainard DM, et al. Sofosbuvir with peginterferon-ribavirin for 12 weeks in previously treated patients with hepatitis C genotype 2 or 3 and cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2015;61:769–75. doi: 10.1002/hep.27567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Poordad F, Hezode C, Trinh R, et al. ABT-450/r-ombitasvir and dasabuvir with ribavirin for hepatitis C with cirrhosis. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1973–82. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1402869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reddy KR, Bourlière M, Sulkowski M, et al. Ledipasvir and sofosbuvir in patients with genotype 1 hepatitis C virus infection and compensated cirrhosis: an integrated safety and efficacy analysis. Hepatology. 2015;62:79–86. doi: 10.1002/hep.27826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zeuzem S, Jacobson IM, Baykal T, et al. Retreatment of HCV with ABT-450/r-ombitasvir and dasabuvir with ribavirin. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1604–14. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1401561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van der Meer AJ, Veldt BJ, Feld JJ, et al. Association between sustained virological response and all-cause mortality among patients with chronic hepatitis C and advanced hepatic fibrosis. JAMA. 2012;308:2584–93. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.144878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Backus LI, Boothroyd DB, Phillips BR, et al. A sustained virologic response reduces risk of all-cause mortality in patients with hepatitis C. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:509–16.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2011.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Younossi ZM, Stepanova M, Marcellin P, et al. Treatment with ledipasvir and sofosbuvir improves patient-reported outcomes: Results from the ION-1, -2, and -3 clinical trials. Hepatology. 2015;61:1798–808. doi: 10.1002/hep.27724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.John-Baptiste AA, Tomlinson G, Hsu PC, et al. Sustained responders have better quality of life and productivity compared with treatment failures long after antiviral therapy for hepatitis C. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:2439–48. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Treloar C, Rance J, Dore GJ, et al. ETHOS Study Group. Barriers and facilitators for assessment and treatment of hepatitis C virus infection in the opioid substitution treatment setting: insights from the ETHOS study. J Viral Hepat. 2014;21:560–7. doi: 10.1111/jvh.12183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Swan D, Long J, Carr O, et al. Barriers to and facilitators of hepatitis C testing, management, and treatment among current and former injecting drug users: a qualitative exploration. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2010;24:753–62. doi: 10.1089/apc.2010.0142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grebely J, Genoway KA, Raffa JD, et al. Barriers associated with the treatment of hepatitis C virus infection among illicit drug users. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;93:141–7. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Doab A, Treloar C, Dore GJ. Knowledge and attitudes about treatment for hepatitis C virus infection and barriers to treatment among current injection drug users in Australia. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40(Suppl 5):S313–20. doi: 10.1086/427446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barua S, Greenwald R, Grebely J, et al. Restrictions for Medicaid reimbursement of sofosbuvir for the treatment of hepatitis C virus infection in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163:215–23. doi: 10.7326/M15-0406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.AASLD/IDSA HCV Guidance Panel. Hepatitis C guidance: AASLD-IDSA recommendations for testing, managing, and treating adults infected with hepatitis C virus. Hepatology. 2015;62:932–54. doi: 10.1002/hep.27950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Myers RP, Shah H, Burak KW, et al. An update on the management of chronic hepatitis C: 2015 Consensus guidelines from the Canadian Association for the Study of the Liver. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;29:19–34. doi: 10.1155/2015/692408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.European Association for Study of Liver. EASL recommendations on treatment of hepatitis C 2015. J Hepatol. 2015;63:199–236. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.The pan-Canadian Pharmaceutical Alliance - February 2016 update. Ottawa: Council of the Federation Secretariat. 2013. [accessed 2015 Dec. 12]. Available www.pmprovincesterritoires.ca/en/initiatives/358-pan-canadian-pharmaceutical-alliance.

- 24.Government of Canada partners with provinces and territories to lower cost of pharmaceuticals [news release]Ottawa: Health Canada. . 2016 Jan. 19. [accessed 2016 July 8]. Available http://news.gc.ca/web/article-en.do?nid=1028339.

- 25.Remis RS. Modelling the incidence and prevalence of hepatitis C infection and sequelae in Canada, 2007: final report. Ottawa: Public Health Agency of Canada. Cat no HP40-39/2009E-PDF. . 2009. [accessed 2015 June 3]. Available www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/sti-its-surv-epi/model/pdf/model07-eng.pdf.

- 26.Uhanova J, Tate RB, Tataryn DJ, et al. The epidemiology of hepatitis C in a Canadian indigenous population. Can J Gastroenterol. 2013;27:336–40. doi: 10.1155/2013/380963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Greenfield SF, Crisafulli MA, Kaufman JS, et al. Implementing substance abuse group therapy clinical trials in real-world settings: challenges and strategies for participant recruitment and therapist training in the Women's Recovery Group Study. Am J Addict. 2014;23:197–204. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2014.12099.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hajarizadeh B, Grebely J, Dore GJ. Epidemiology and natural history of HCV infection. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;10:553–62. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2013.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Drugs for chronic hepatitis C infection: recommendations report - CADTH therapeutic review. Ottawa: Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health. 2015. [accessed 2015 Dec. 15]. Available https://www.cadth.ca/sites/default/files/pdf/TR0008_HepatitisC_RecsReport_e.pdf. [PubMed]

- 30.Graham J. Medicaid, private insurers begin to life curbs on pricey hepatitis C drugs. Kaiser Health News. 2016 July 5. [accessed 2016 July 7]. Available http://khn.org/news/medicaid-private-insurers-begin-to-lift-curbs-on-pricey-hepatitis-c-drugs/

- 31.Aspinall EJ, Corson S, Doyle JS, et al. Treatment of hepatitis C virus infection among people who are actively injecting drugs: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;57(Suppl 2):S80–9. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martin NK, Vickerman P, Miners A, et al. Cost-effectiveness of hepatitis C virus antiviral treatment for injection drug user populations. Hepatology. 2012;55:49–57. doi: 10.1002/hep.24656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Scott N, Iser DM, Thompson AJ, et al. Cost-effectiveness of treating chronic hepatitis C virus with direct-acting antivirals in people who inject drugs in Australia. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;31:872–82. doi: 10.1111/jgh.13223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Martin NK, Vickerman P, Grebely J, et al. Hepatitis C virus treatment for prevention among people who inject drugs: modeling treatment scale-up in the age of direct-acting antivirals. Hepatology. 2013;58:1598–609. doi: 10.1002/hep.26431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hepatitis C medicines fact sheet for consumers - Who can prescribe these new treatments? The Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme, Department of Health, Australian Government. [updated 2016 May 1) (accessed 2016 July 11]. Available www.pbs.gov.au/info/publication/factsheets/hep-c/factsheet-for-patients-and-consumers.

- 36.July 2015 PBAC meeting - positive recommendations. The Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme, Department of Health, Australian Government. [accessed 2016 Jan. 5]. Available www.pbs.gov.au/industry/listing/elements/pbac-meetings/pbac-outcomes/2015-07/web-outcomes-july-2015-positive-recommendations.pdf.

- 37.Gartrell A. Turnball government to spend $1 billion on hepatitis C 'miracle cures' for all. Sydney Morning Herald. 2015 Dec. 20. [accessed 21 Dec. 2015]. Available www.smh.com.au/federal-politics/political-news/turnbull-government-to-spend-1-billion-on-hepatitis-c-miracle-cures-for-all-20151219-glrib0.html.

- 38.Reimbursements for new treatment for chronic hepatitis C during March to July 2016. Monitoring hepatitis C treatment uptake in Australia Newsletters 2016 Sept. issue 5. Sydney: The Kirby Institute for infection and immunity in society, University of New South Wales. [accessed 2016 Oct. 11]. Available http://kirby.unsw.edu.au/research-programs/vhcrp-newsletters.

- 39.Webster P. Consensus mounts for national drug formulary. CMAJ. 2016;188:E180. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.109-5281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lo Re V, Gowda C, Urick PN, et al. Disparities in absolute denial of modern hepatitis C therapy by type of insurance. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:1035–43. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2016.03.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Younossi ZM, Bacon BR, Dieterich DT, et al. Disparate access to treatment regimens in chronic hepatitis C patients: data from the TRIO network. J Viral Hepat. 2016;23:447–54. doi: 10.1111/jvh.12506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Grebely J, Litwin A, Dore GJ. Addressing reimbursement disparities for direct-acting antiviral therapies for hepatitis C virus infection is essential to ensure access for all. J Viral Hepat. 2016;23:664–6. doi: 10.1111/jvh.12550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Prince Edward Island to introduce new lifesaving hepatitis C strategy [press release]. Charlottetown: Department of Health and Wellness, Prince Edward Island Canada. 2015. [accessed 2015 Dec. 11]. Available www.gov.pe.ca/health/index.php3?number=news&dept=&newsnumber=10059&lang=E.

- 44.Milliken D, Venkatesh J, Yu R, et al. Comparison of drug coverage in Canada before and after the establishment of the pan-Canadian Pharmaceutical Alliance. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e008100. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Combating hepatitis B and C to reach elimination by 2030 - advocacy brief. Geneva: World Health Organization. 2016. [accessed 2016 June 24]. Available www.who.int/hepatitis/publications/hep-elimination-by-2030-brief/en/

- 46.Fourth National Hepatitis C Strategy 2014-2017. Department of Health, Australian Government. 2014. [accessed 11 Dec. 2015]. Available www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/ohp-bbvs-hepc.

- 47.Hepatitis C action plan for Scotland - Phase I: September 2006-August 2008. Edinburgh: The Scottish Government. 2006. [accessed 2015 Dec. 11]. Available www.gov.scot/Resource/Doc/148746/0039553.pdf.

- 48.Hepatitis C action plan for Scotland - Phase II: May 2008-March 2011. Edinburgh: The Scottish Government. 2008. [accessed 2015 Dec. 11]. Available www.gov.scot/resource/doc/222750/0059978.pdf.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.