Abstract

Background:

Recent meta-analyses of the efficacy of probiotics for preventing diarrhea associated with Clostridium difficile have concluded there is a large effect favouring probiotics. We reexamined this evidence, which contradicts the results of a more recent large randomized controlled trial that found no benefit of Lactobacillus probiotics for preventing C. difficile-associated diarrhea.

Methods:

We performed a systematic review of the efficacy of treatment with Lactobacillus probiotics for preventing nosocomial C. difficile-associated diarrhea in adults and carried out a meta-analysis using a Bayesian hierarchical model. We used credibility analysis and meta-regression to characterize the heterogeneity between studies.

Results:

Ten studies met our inclusion criteria. The pooled risk ratio was highly statistically significant, at 0.25 (95% credible interval 0.08-0.47). However, the 95% prediction interval for the risk ratio in a future study, 0.02-1.34, was wider than the credible interval, owing to heterogeneity between studies. Furthermore, a credibility analysis showed that the strength of the evidence was weaker than the observed number of cases of C. difficile-associated diarrhea across studies would suggest. Meta-regression suggested that the beneficial effect of probiotics was more likely to be reported in studies with an increased risk of C. difficile-associated diarrhea in the control group, although this association was not statistically significant.

Interpretation:

Accounting for between-study heterogeneity showed that there is considerable uncertainty regarding the apparently large efficacy estimate associated with Lactobacillus probiotic treatment in preventing C. difficile-associated diarrhea. Most studies to date have been carried out in populations with a low risk of C. difficile-associated diarrhea, such that the evidence is inconclusive and inadequate to support a policy concerning routine use of probiotics in to prevent this condition.

Diarrhea associated with Clostridium difficile results in significant morbidity in inpatients.1,2 Its manifestations range from debilitating diarrhea to toxic megacolon requiring surgical intervention to death.3 Nosocomial diarrhea due to C. difficile is strongly associated with antibiotic therapy,4 with the mechanism of risk believed to be antibiotic-related disruption of the intestinal flora. At the institutional level, prevention is by infection-control measures. At the patient level, there has been great interest in reestablishing normal biota via fecal transfer in recurrent C. difficile infection5 and especially by prophylactic administration of purified microbial preparations ("probiotics"), given their low cost and easy availability. Consistently, meta-analyses have estimated a protective effect of probiotics of various strains against nosocomial C. difficile-associated diarrhea,6-9 on the basis of a clinically heterogeneous group of small to medium-sized studies of generally low to moderate quality. However, a recent large, well-run study failed to show a statistically significant preventive effect of a mixture of Lactobacillus acidophilus and bifidobacteria on C. difficile-associated diarrhea in older inpatients.10

Such discrepancies between the results of early meta-analyses and subsequent large randomized trials (RCTs) have previously been noted11 and have been attributed to publication bias in the form of selected publication of small RCTs reporting optimistic results. In the case of meta-analyses of probiotics for preventing C. difficile-associated diarrhea, we believe that an additional problem is that standard statistical methods may have underestimated the statistical heterogeneity between the published studies and exaggerated the precision in the pooled effect size. Meta-analyses published to date6-9 have used the traditional DerSimonian-Laird random-effects model for meta-analysis,12 which is known to underestimate heterogeneity.13

Our objective was to conduct a systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs of the efficacy of treatment with Lactobacillus spp. probiotics for preventing diarrhea due to C. difficile in adult patients, while examining the issue of between-study heterogeneity more thoroughly by applying a Bayesian hierarchical meta-analysis model.

Methods

To ensure proper reporting of this systematic review and meta-analysis, we completed the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) checklist14 (available at www.cmajopen.ca/content/4/4/E706/suppl/DC1).

Literature search

The search covered PubMed, Embase, the Cochrane Library, CINAHL and ClinicalTrials.gov. Search terms included "probiotic*" (where the asterisk indicates a wild card), "Lactobacill*" and terms specific for the organisms themselves, combined with "antibiotic associated diarrhea," "Clostridium" or "difficile" (Appendix 1, available at www.cmajopen.ca/content/4/4/E706/suppl/DC1). The search was last updated on Dec. 20, 2015. In addition, we closely reviewed the included and excluded papers from published systematic reviews and meta-analyses for inclusion. We summarized the results using a PRISMA flow diagram.14

Inclusion criteria

To be included in the meta-analysis, a study had to have been published in a peer-reviewed journal and described as a double-blind RCT recruiting predominately or exclusively adult in-patients who were receiving antibiotics of any kind and for any indication, and who were not described as having active diarrhea. By double-blinding we meant blinding of patients and study personnel responsible for measuring outcomes. This reduced the risk of ascertainment bias of cases of C. difficile-associated diarrhea in studies with incomplete testing and enabled us to use a "missing at random" assumption to adjust for missing data (see Statistical analysis section). The active treatment had to contain Lactobacillus species at any dosage. We included studies using different dosages and formulations of Lactobacillus probiotics. We excluded yeast studies to reduce the heterogeneity of interventions as well as studies in children and those involving community-acquired C. difficile-associated diarrhea because these represented different populations. C. difficile-associated diarrhea had to be defined as diarrhea in a patient with a positive result of culture or toxin assay for C. difficile, and the paper had to report sufficient information about numbers tested to allow for adjustment for incomplete testing for C. difficile.

Data abstraction and risk of bias assessment

Three of the authors (A.S., X.X. and L.S.) carried out the literature searches, review of study quality and data extraction. From each study we extracted the number of patients randomly assigned to the intervention and placebo groups, the numbers of patients who had antibiotic-associated diarrhea in each group, the number who were tested for C. difficile and the number who were classified as having C. difficile-associated diarrhea. In addition, we extracted descriptive information (study location, inclusion criteria, probiotic strain and dosage, method of testing for C. difficile and source of funding) and patient demographic characteristics and covariates (mean age, proportion by sex, and proportion receiving each group or class of antibiotics). We assessed the risk of major biases described by the Cochrane Collaboration (selection, treatment, attrition and detection) as "no," "yes" or "unclear" (which included instances where we had insufficient information to assess risk of bias). We then classified studies as A (no major sources of bias), B (1 possible source of bias) or C (≥ 2 possible sources of bias). Detailed scoring is given in Appendix 1.

Statistical analysis

Our primary outcome of interest was nosocomial C. difficile-associated diarrhea. We analyzed the data for all patients randomly allocated to a study group in each study, assuming first that patients who had no recorded antibiotic-associated diarrhea were negative for this condition and second that missing information on the results of testing for C. difficile in patients with antibiotic-associated diarrhea was missing at random. The latter assumption was based on the expectation that, since we selected double-blinded studies, the group to which a patient was randomly allocated could not influence the decision to test for C. difficile-associated diarrhea. For each study we estimated the risk of diarrhea due to C. difficile in the probiotics and placebo groups and the risk ratio (RR) comparing them. In cases in which the study design included 2 probiotics groups (low and high dosage), we combined probiotic users into a single group.

There was considerable heterogeneity in the risk of C. difficile-associated diarrhea in the placebo group of the studies selected. To examine the relation between this risk and the reported effect size, we used a L'Abbé plot. The L'Abbé plot is a plot of the observed risk of C. difficile-associated diarrhea in the probiotics group versus the observed risk of this condition in the control group. Deviation from the diagonal line would suggest that there is an association between the risk of C. difficile-associated diarrhea in the control group and the reported RR. To investigate the presence of publication bias, we used a funnel plot to assess the relation between the log RR and its standard error reported in the individual studies.

Bayesian meta-analysis

We used an exact Bayesian random-effects meta-analysis model to pool RRs across studies while accounting for the heterogeneity within and between studies.15 The Bayesian approach is an alternative to the classical (frequentist) approach for statistical inference. A Bayesian analysis requires specification of a prior distribution for each of the unknown parameters in the model, namely the pooled RR and the between-study standard deviation in the case of our meta-analysis model. The prior distribution reflects any information we have about the parameter from a source external to the observed data. In our primary analyses we wished to ensure that the influence of external information on our conclusions was negligible. Hence we used vague or noninformative prior distributions (see Appendix 1 for details of prior distributions we used). Figure 1 gives a general description of the role of prior information in a Bayesian analysis.

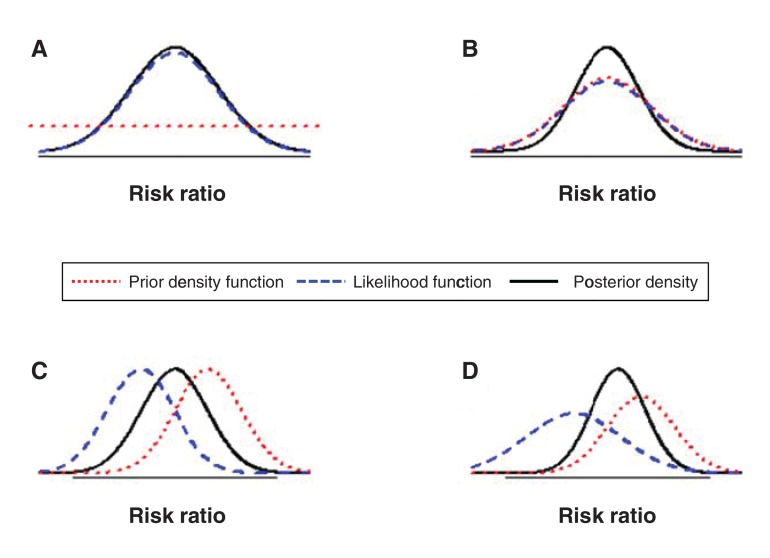

Figure 1.

Role of the prior distribution in a Bayesian analysis. A Bayesian analysis combines the information on the unknown parameters (e.g., the pooled risk ratio) from the prior distribution and from the observed data in accordance with Bayes' theorem. The result is expressed as the posterior distribution of the unknown parameters. The prototypical figures above illustrate how the posterior distribution is influenced by both the prior distribution and information from the observed data. Each figure presents the prior density function, the likelihood function (or the information from the observed data) and the posterior density. When a function is concentrated over a narrow area it is more informative. The more spread out a function, the less informative it is. In Figure A, a vague prior distribution is used. The flat red line indicates that the prior distribution is highly spread out, placing equal weight on all possible values. The posterior distribution (black line) is determined almost entirely by the observed data (blue line). Therefore, the prior distribution has little or no influence over the final results. In the remaining figures, the prior distribution is more informative and has an influence on the final results. In Figure B, both prior distribution and likelihood are in perfect agreement, resulting in a posterior distribution that is more informative than either of them. In Figure C, the prior distribution and the likelihood are equally informative, resulting in the posterior distribution's being between them. In Figure D, the prior distribution is more informative than the likelihood, resulting in a posterior distribution that is located closer to the prior distribution.

The meta-analysis provides estimates of the pooled RR and between-study standard deviation and their respective 95% credible intervals (CrIs). The 95% CrI is the Bayesian equivalent of the frequentist 95% confidence interval. It can be interpreted as an interval that includes the unknown measure with 95% probability. In addition, the Bayesian meta-analysis also provides a predicted RR. Whereas the pooled RR represents the average across studies, the predicted RR represents the RR in a future study. If the between-study standard deviation is high, we would expect the prediction interval (around the predicted RR) to be much wider than the CrI for the pooled RR. We also estimated the I2 statistic, a measure of consistency, together with its CrI using the approach described by Higgins and Thompson.16

As the Bayesian analysis provides the entire posterior distribution for each unknown measure (Figure 1), it is possible to estimate the probability that the unknown measure lies below a certain cut-off. We estimated the posterior probability that the predicted RR lies below 1.

Credibility analysis

We carried out a Bayesian credibility analysis as an additional approach to characterize the extent of uncertainty about the pooled result.17,18 This analysis makes use of the prior distribution feature in a Bayesian analysis to gauge the credibility of the information in the observed data. It can be applied when the pooled RR from the meta-analysis is significantly different from 1 when using a vague prior distribution. Credibility analysis asks "How skeptical do we have to be to not believe this statistically significant result?" or, more specifically, "What skeptical prior distribution would render the pooled RR nonsignificant?"

The result of the credibility analysis is the "critical" skeptical prior distribution, which can convert the pooled RR from significant to nonsignificant (i.e., such that the posterior CrI of the pooled RR includes 1). It is a symmetric distribution centred at the RR of 1. When the results of individual studies are consistent and precise, the critical skeptical prior distribution would need to be highly concentrated around 1 to induce a change in conclusions (high degree of skepticism). When the results from individual studies are inconsistent and imprecise, the critical skeptical prior distribution would be more spread out around 1 (low to moderate degree of skepticism). If an unreasonably high degree of skepticism is needed to alter our conclusions, it would suggest that the data are consistent or credible. If a reasonably skeptical prior distribution is adequate, it would suggest that the data are inconsistent and not credible.

Classical (frequentist) meta-analysis

For comparison with standard meta-analytical techniques, we also used the widely applied approximate meta-analysis method described by DerSimonian and Laird,12 which has been used in previous meta-analyses of the same research question. We also implemented 1 other frequentist method (the Sidik-Jonkman method), which has been described with the goal of improving estimation of between-study heterogeneity compared with the DerSimonian-Laird method.13 From each of these analyses we extracted the pooled RR, between-study standard deviation, p value of the Q-statistic (a test for heterogeneity) and I2 statistic.

Here as well we adjusted the results in studies with incomplete testing. To do this we assumed that the rate of positive results of testing for C. difficile-associated diarrhea among patients who were not tested was the same as the observed proportion among those who were tested, separately within probiotics and placebo groups. For studies that had 0 cells in the cross-tabulation between probiotics and C. difficile-associated diarrhea, we added 0.5 to all cells to avoid problems due to zero proportions.

Examining sources of heterogeneity

We examined possible sources of between-study heterogeneity using Bayesian meta-regression models,18 relating the pooled RR to different covariates 1 at a time. We considered the covariate study quality (no major sources of bias identified [A] v. at least 1 source of bias identified [B or C]), population prevalence of C. difficile-associated diarrhea (as estimated by the adjusted proportion of patients with this condition in the placebo group, either as a continuous variable or dichotomized at the median value < 6% v. ≥ 6%), composition of the probiotic (preparations containing only Lactobacillus spp. v. mixed preparations), dosage of probiotic (dichotomized at the median value of < 50 v. ≥ 50 million colony-forming units as well as treating dosage as a continuous variable) and whether studies received industry funding (any support v. none). The absolute risk difference statistic may be considered easier to interpret than the relative risk when evaluating the impact of variable risk of diarrhea due to C. difficile across studies. Therefore, for this variable alone, we also estimated the pooled absolute risk difference after stratifying studies by the risk of C. difficile-associated diarrhea in the placebo group (< 6% v. ≥ 6%). The Bayesian approach allows estimation of the probability of an association, i.e., the probability that the meta-regression coefficient is greater than 0. Probabilities close to 0 or 1 are indicative of an association. The Bayesian approach also addresses problems that have been previously identified with meta-regression models adjusting for the control group risk.19

Sensitivity analysis

We conducted several sensitivity analyses to study the robustness of our Bayesian analysis. First, we varied the prior distribution over the standard deviation of the between-study heterogeneity, as this is known to influence the results of the meta-analysis.18 Second, we conducted a meta-analysis including the results of the 2 studies that did not report information on testing to see whether they were systematically different from those in our primary analysis, assuming, as the authors did, that untested patients were negative for diarrhea due to C. difficile. We performed a sensitivity analysis that excluded the study by Gao and colleagues,20 reasoning that their results were not generalizable to other settings owing to the extremely high risk of C. difficile-associated diarrhea reported in the placebo group. We also performed a sensitivity analysis limiting inclusion to the 5 studies that used a stricter definition of diarrhea (≥ 3 liquid stools in 24 hours).

Software

We carried out Bayesian analyses using WinBUGS version 1.4.3 for Windows.21 We implemented the frequentist analysis using the R statistical software version 3.0.1 and the R package metafor version 2.22 We obtained descriptive statistics and graphs using the R 3.0.1 or SAS 9.3 statistical software packages. Programs and data used for the primary analyses are given in Appendix 1.

Quality of evidence

We used the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation) guidelines23 to transparently summarize our rating regarding the quality of the evidence on the efficacy of Lactobacillus probiotics for prevention of C. difficile-associated diarrhea.

Results

Literature search

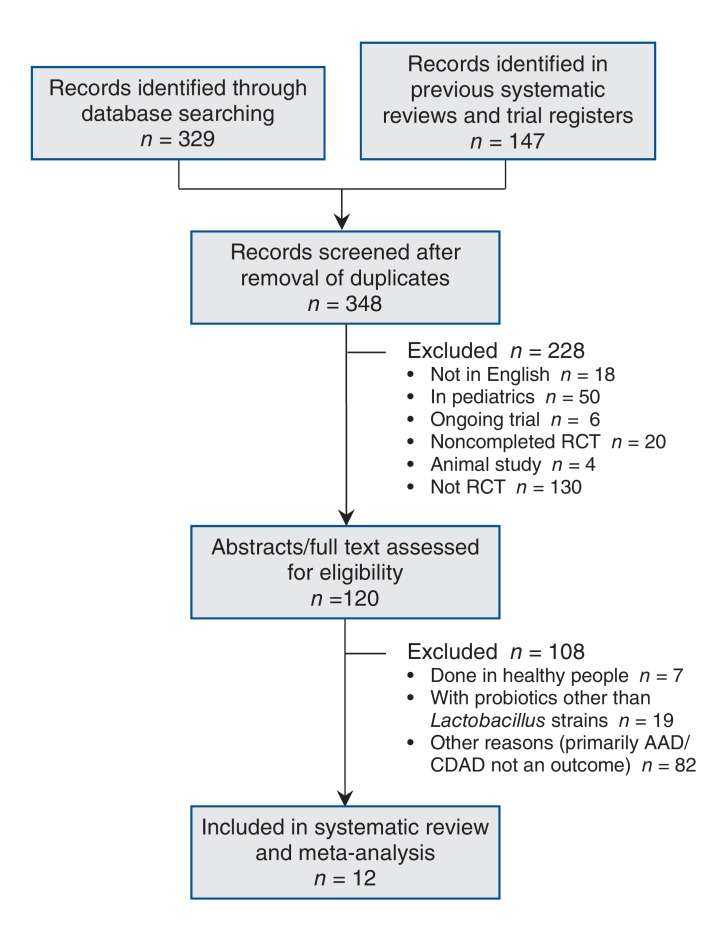

Our search identified 10 trials that qualified for inclusion10,20,24-31 (Figure 2, Table 1). In addition, 2 trials were included only in a sensitivity analysis of unadjusted data because we could not obtain information on the number tested for C. difficile-associated diarrhea.32,33 In total, we excluded 108 RCTs (Figure 2). Of these, 1 was excluded because the separation of cases that were positive for C. difficile toxin between the probiotics and placebo groups was unclear,34 a second trial was excluded because the patients had active diarrhea at enrolment,35 and a third trial was excluded because it was not blinded.36 Two other trials were excluded because they were published in abstract form only.37,38

Figure 2.

Flow chart showing study selection. AAD = antibiotic-associated diarrhea, CDAD = Clostridium-difficile-associated diarrhea, RCT = randomized controlled trial.

Table 1: Summary of design and risk of bias in randomized controlled trials of probiotics in the prevention of diarrhea associated with Clostridium difficile.

| Author, year | Definition of diarrhea | Method for detecting C. difficile | Sample size | Probiotic dosage,CFUs × 109* | Treatment duration | Length of follow-up | Risk of bias† | Industry funded‡ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ouwehand et al.,24 2014 | ≥ 3 stools Bristol scale 7 | GDH and toxin A EIA; toxin B by cell culture | Pro-2 168 Pro-1 168 Pla 167 |

LA, LPl, B (capsule; L pro-1 4.7, pro-2 17) | Duration of antibiotic treatment + 7 d | 4 wk (post antibiotic treatment) | A | Yes |

| Allen et al.,10 2013 | ≥ 3 stools Bristol scale 5-7, or looser than normal by patient report, in 24 h | In-house tissue culture assay + EIA for toxins or ELFA for toxins or GDH and toxin A EIA | Pro 1493 Pla 1488 |

LA, B (capsule; all 60) | 21 d | 8 wk total for AAD/ 12 wk for CDAD | A | No |

| Selinger et al.,25 2013 | ≥ 3 stools Bristol scale 6-7 | ELFA for toxins or GDH and toxin A EIA | Pro 112 Pla 117 |

LA, LPl, LPa, LD, B, ST (powder; all 450) | Duration of antibiotic treatment + 7 d | 4 wk (post pro/pla treatment) | B | Yes |

| Gao et al.,20 2010 | ≥ 3 liquid stools in 24 h | Triage panel (not specified) and toxin B by cell culture | Pro-2 86 Pro-1:85 Pla 84 |

LA, LC (capsule; pro-1 L 50, pro-2 L 100) | Duration of antibiotic treatment + 5 d | 21 d | A | Yes |

| Sampalis et al.,26 2010 | ≥ 1 episodes unformed or liquid stool in 24 h | Toxin A and B (not specified) | Pro 216 Pla 221 |

LA, LC (milk; L 50) | Duration of antibiotic treatment + 5 d | 21 d | C | Yes |

| Safdar et al.,27 2008§ | Watery or liquid stools for ≥ 2 consecutive days | Toxin (not specified) | Pro 23 Pla 17 |

LA (capsule; L 20) | Pro 22.8 (9.4) d, pla 24.5 (4.8) d | NR | B | No |

| Beausoleil et al.,28 2007 | ≥ 3 liquid stools in 24 h | Cytotoxin assay (not specified) | Pro 44 Pla 45 |

LA and LC (milk; L 50) | Duration of antibiotic treatment | 21 d | C | Yes |

| Hickson et al.,29 2007 | ≥ 2 liquid stools daily in excess of normal for ≥ 2 d | Toxin (not specified) | Pro 69 Pla 66 |

LC, LB, ST (yogourt; L 0.1, 0.01, O 0.1) | Duration of antibiotic treatment + 7 d | 28 d | A | No |

| Plummer et al.,30 2004¶ | NA | Latex agglutination or EIA for toxins | Pro 69 Pla 69 |

LA, B (capsule, total 20) | 20 d | NR | C | Yes |

| Heimburger et al.,31 1994 | > 200 g stool in 24 h | Culture and titres | Pro 16 Pla 18 |

LA, LB (granules, dosage not given) | ≥ 5 d | 5 d | C | No |

Note: AAD = antibiotic-associated diarrhea, B = Bifidobacterium, CDAD = Clostridium-difficile-associated diarrhea, CFUs = colony-forming units, EIA = enzyme immunoassay, ELFA = enzyme-linked fluorescent assay, GDH = glutamate dehydrogenase, L = Lactobacillus spp., LA = L. acidophilus, LB = L. bulgaricus, LC = L. casei, LD = L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus, LPa = L. paracasei, LPl = L. plantarum, NA = not available, NR = not reported, Pla = placebo, Pro = probiotics, ST = Streptococcus thermophilus.

*Dosage is given in colony-forming units unless specified otherwise. Where 2 figures are given, the first represents the total dosage of Lactobacillus species (L), and the second the dosage of other species (O).

†A = no major sources of bias, B = 1 possible source of bias, C = ≥ 2 possible sources of bias.

‡Included direct study sponsorship. We did not consider supply of investigational material without conditions or support for activities not associated with the study as support from the manufacturer.

§Treatment duration is given as mean and standard deviation. Although follow-up was mentioned as part of the study design, the precise duration was not reported.

¶Follow-up was post discharge, but no details were given as to treatment duration post intervention or post discharge.

Included trials ranged in size from 34 to 2981 patients and were conducted in Canada, the United States, the United Kingdom and China. The studies were published between 1994 and 2014. Patients received Lactobacillus spp. as single preparations or in combination, in dosages ranging from < 20 to 450 billion colony-forming units (the latter figure was a total dosage of a mixed preparation), given as yoghourt, capsules or powder. A variety of definitions of diarrhea were used, allowing for 1 to 3 liquid stools over 1 to 3 days, with or without application of a formal scale. Details of the studies' design, including definition of diarrhea, probiotic and dosage, assay for C. difficile, length of treatment and length of follow-up, are summarized in Table 1. In 6 of the 10 studies, there was a concern for risk of bias on the dimensions we considered (Table 1, Appendix 1).

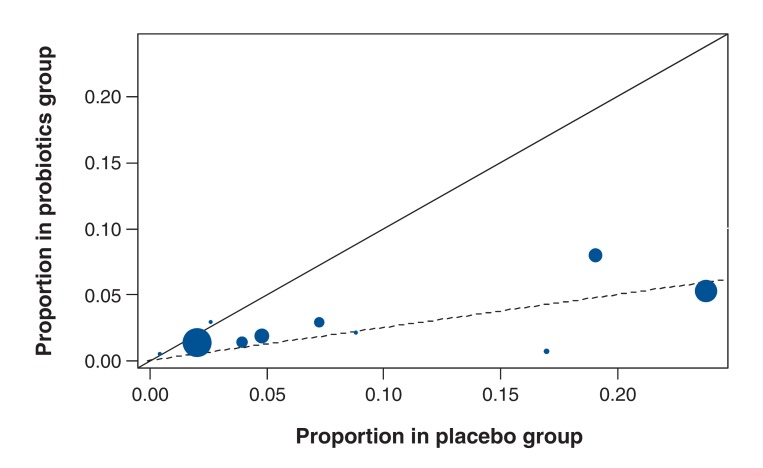

Risk of C. difficile-associated diarrhea

After adjustment for incomplete testing for C. difficile in 5 studies, the proportion of patients with C. difficile-associated diarrhea in the probiotics group ranged from 0%-8%, and in the placebo group from 0%-24% (Table 2, Figure 3). In 2 studies, no cases of C. difficile-associated diarrhea were identified. In total, the condition was detected in 45/2554 patients in the probiotics group and 90/2287 patients in the placebo group. The deviation of the L'Abbé plot from the diagonal (Figure 3) suggests that studies that reported a greater risk of C. difficile-associated diarrhea in the placebo group also reported a greater benefit of probiotics.

Table 2. Estimated risk of antibiotic-associated diarrhea, proportion of patients tested for diarrhea associated with Clostridium difficile and adjusted risk of C. difficile-associated diarrhea in the probiotic and placebo groups*.

| Author, year | Risk of AAD, no. of patients/ total no. of patients (%) | CDAD testing, no. of patients/total no. (%) with AAD | Risk of CDAD among those tested† (%) | Adjusted risk of CDAD, %‡ | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Probiotic | Placebo | Probiotic | Placebo | Probiotic | Placebo | Probiotic | Placebo | |

| Ouwehand et al.,24 2014 | 33/168 (19.6) 21/168 (12.5) |

41/167 (24.6) | 33/33 (100) 21/21 (100) |

41/41 (100) | 3/33 (9.1) 3/21 (14.3) |

8/41 (19.5) | 1.8 | 4.8 |

| Allen et al.,10 2013 | 159/1493 (10.6) | 153/1488 (10.3) | 93/159 (58.5) | 88/153 (57.5) | 12/93 (12.9) | 17/88 (19.3) | 1.4 | 2.0 |

| Selinger et al.,25 2013 | 5/117 (4.3) | 10/112 (8.9) | 5/5 (100) | 4/10 (40.0) | 0/5 (0) | 0/4 (0) | 0 | 0 |

| Gao et al.,20 2010 | 13/86 (15.1) 24/85 (28.2) |

37/84 (44.0) | 13/13 (100) 24/24 (100) |

37/37 (100) | 1/13 (7.7) 8/24 (33.3) |

20/37 (54.1) | 5.3 | 23.8 |

| Sampalis et al.,26 2010 | 47/216 (21.8) | 65/221 (29.4) | 16/47 (34.0) | 30/65 (46.2) | 1/16 (6.2) | 4/30 (13.3) | 1.4 | 3.9 |

| Safdar et al.,27 2008 | 4/23 (17.4) | 6/17 (35.3) | 3/4 (75.0) | 4/6 (66.7) | 0/3 (0) | 1/4 (25.0) | 0 | 8.8 |

| Beausoleil et al.,28 2007 | 7/44 (15.9) | 16/45 (35.6) | 2/7 (28.6) | 13/16 (81.2) | 1/2 (50.0) | 7/13 (53.8) | 8.0 | 19.1 |

| Hickson et al.,29 2007 | 7/69 (10.1) | 19/66 (28.8) | 7/7 (100) | 19/19 (100) | 0/56 (0) | 9/53 (17.0) | 0 | 13.6 |

| Plummer et al.,30 2004 | 15/69 (21.7) | 15/69 (21.7) | 15/15 (100) | 15/15 (100) | 2/15 (13.3) | 5/15 (33.3) | 2.9 | 7.2 |

| Heimburger et al.,31 1994 | 5/16 (31.2) | 2/18 (11.1) | 5/5 (100) | 2/2 (100) | 0/5 (0) | 0/2 (0) | 0 | 0 |

Note: AAD = antibiotic-associated diarrhea, CDAD = Clostridium-difficile-associated diarrhea.

*Some studies had 2 probiotic groups.

†The denominator is the number of patients with AAD who were tested for CDAD. Values are before adjustment for missing data.

‡Obtained by multiplying the risk of AAD by the risk of CDAD among those tested, under the assumption that the missing test results were missing at random.

Figure 3.

L'Abbé plot showing the proportion of patients in the probiotics and placebo groups with Clostridium-difficile-associated diarrhea. The area of the circles is proportional to the precision of the outcomes. The solid (diagonal) line has a slope of 1. The dashed line, which has a slope equal to the pooled risk ratio from the Bayesian analysis, indicates that the observed studies deviate from the solid line.

Exploration of publication bias

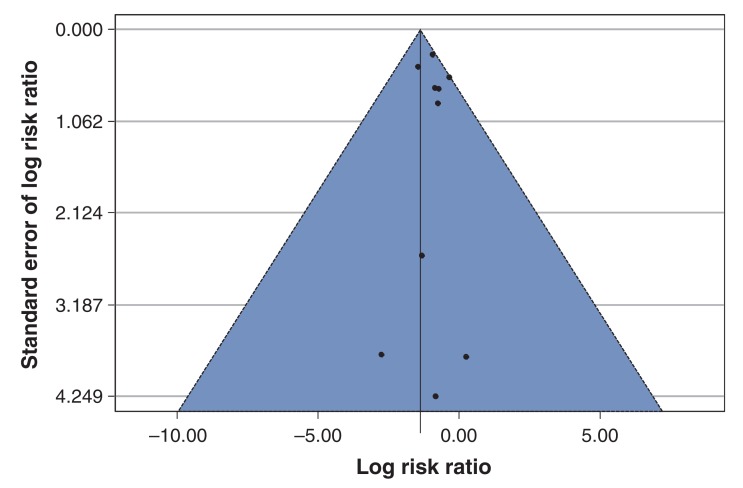

The funnel plot (Figure 4) did not clearly show asymmetry in the scatter of points across studies. However, this interpretation is limited by the small number of studies and the presence of heterogeneity between the studies.39

Figure 4.

Funnel plot of studies included in meta-analysis of Lactobacillus treatment in prevention of Clostridium-difficile-associated diarrhea. The solid line in the centre is at the pooled log risk ratio from the Bayesian meta-analysis with the vague prior distribution. The two dashed lines on either side demarcate a 95% pseudo confidence region.

Bayesian meta-analysis

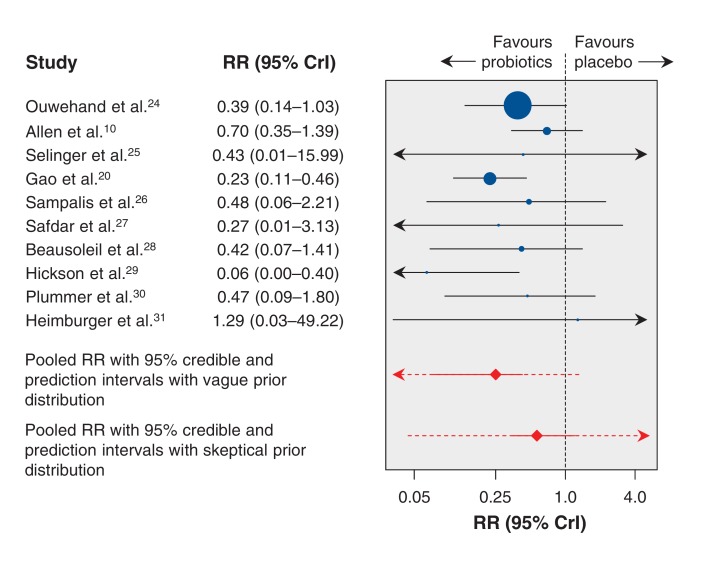

A forest plot summarizing the results of the Bayesian hierarchical meta-analysis is presented in Figure 5. The RRs of probiotic versus placebo for individual studies ranged from 0.06 to 1.29, with only 2 studies reporting a statistically significant RR.20,29

Figure 5.

Forest plot summarizing results of Bayesian hierarchical meta-analysis. The plot shows the pooled risk ratio (red diamond) and 95% credible interval (solid red line) and 95% prediction interval (dotted red line) estimated by means of a Bayesian meta-analysis with a vague prior distribution, and the pooled risk ratio and 95% credible and prediction intervals from a Bayesian meta-analysis with a critical skeptical prior distribution. Values less than 1.0 favour Lactobacillus probiotics. CrI = credible interval, RR = risk ratio.

The median pooled RR was estimated to be 0.25 (95% CrI 0.08-0.47), indicating a statistically significant association on average between Lactobacillus probiotic treatment and a lower risk of C. difficile-associated diarrhea, with a 75% risk reduction relative to placebo (Table 3). The between-study standard deviation on the log RR scale was 0.64 (95% CrI 0.06-1.75), which was relatively high, indicating considerable statistical heterogeneity between studies (Table 3).

Table 3: Comparison of results from Bayesian and frequentist random-effects meta-analysis models.

| Measure | Bayesian meta-analysis | Frequentist meta-analysis | |

|---|---|---|---|

| DerSimonian-Laird approach | Sidik-Jonkman approach | ||

| Overall measure of treatment effect: pooled risk ratio (95% interval)* | 0.25 (0.08-0.47) | 0.42 (0.29-0.59) | 0.37 (0.21-0.65) |

| Measures of between-study heterogeneity | |||

| Between-study variance (log risk ratio scale) (95% interval)* | 0.64 (0.06-1.75) | 0.02 (SE 0.19) | 0.27 (SE 0.26) |

| Q-test p value | - | 0.4029 | 0.4029 |

| 95% prediction interval for risk ratio | 0.02-1.34 | 0.24-0.69† | 0.09-1.45† |

| P (predicted risk ratio < 1) | 0.96 | - | - |

| I2 statistic (95% interval), %* | 67.4 (1.6-96.7) | 4 (0-64) | 41.26 (0-77) |

Note: SE = standard error.

*95% credible interval for the Bayesian meta-analysis, 95% confidence interval for the frequentist meta-analyses.

†Calculated by means of the methods described by Higgins and colleagues.45

The prediction interval for the RR in a future study was 0.02-1.34. This is much wider than the 95% CrI for the pooled RR owing to the high between-study heterogeneity. Nonetheless, we found that the probability that the predicted RR was less than 1 was 0.96. This means that, despite the apparently wide prediction interval, the evidence in the data suggests that there is a probability of 0.96 that the true RR in a future study will lie below 1.

The I2 statistic was 67.4% (95% CrI 1.6%-96.7%), once again reflecting a high degree of inconsistency between studies (Table 3).

Credibility analysis

The critical skeptical prior distribution over the pooled RR was centred at 1, and its 95% CrI ranged from 0.6 to 1.8. This means a skeptic with a prior opinion that the true RR is most likely to range anywhere from 0.6 to 1.8 would remain unconvinced by the results of our meta-analysis despite the apparently large, statistically significant effect of Lactobacillus probiotics.

When we used this skeptical prior distribution, the pooled RR was 0.57 (95% CrI 0.34-1.15) (Figure 5). The prediction interval was 0.04-14.67, and the probability that the predicted RR was less than 1 decreased to 0.73.

We considered the range of the critical skeptical prior distribution to be quite spread out and reflective of a reasonable degree of skepticism, as it is unusual for a pharmaceutical intervention to be associated with an RR outside of the range of 0.6-1.8. Thus, the credibility analysis suggests that the evidence in favour of probiotics was not very robust and the final conclusion could be altered by use of a moderately informative prior distribution.

The information in the critical skeptical prior distribution can also be expressed as being equivalent to information from a balanced, null RCT with 30 events observed in each arm.18 In other words, although the total number of cases of C. difficile-associated diarrhea was 135 in the studies included in the meta-analysis, the combined information across the studies was relatively weak and could be displaced by information from a trial with only 60 observed cases of C. difficile-associated diarrhea.

Comparison of Bayesian and frequentist meta-analyses

All 3 models reached the conclusion that there is a statistically significant reduction in risk of C. difficile-associated diarrhea associated with Lactobacillus probiotic treatment (Table 3). However, the DerSimonian-Laird method led to the conclusion that there is no between-study heterogeneity. This is reflected in the low values of both the between-study standard deviation and the I2 statistic, and a prediction interval that is also highly statistically significant. The Sidik-Jonkman method resulted in a larger estimate for between-study variance and correspondingly wide prediction interval and a high value of the I2 statistic, reflecting the heterogeneity between studies.

Exploration of sources of between-study heterogeneity

There was no conclusive evidence of an association between the pooled RR and any of the covariates we examined, with the 95% CrIs for the regression coefficient including 0 in all cases (Table 4). Nonetheless, the probability of an association with the risk of C. difficile-associated diarrhea in the placebo group was high.

Table 4: Results of meta-regression models.

| Potential source of heterogeneity | Subgroup;* no. of studies | RR (95% CrI) in subgroups | Meta-regression coefficient (95% CrI) |

p value (meta-regression coefficient > 0)† |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study quality | B or C: 6 A: 4 |

0.17 (0.03 to 0.64) 0.27 (0.07 to 0.71) |

0.4 (-1.3 to 2.4) | 0.70 |

| Type of probiotic | Mixture: 5 Lactobacillus only: 5 |

0.31 (0.07 to 0.68) 0.17 (0.04 to 0.57) |

-0.56 (-2.1 to 1.3) | 0.26 |

| Probiotic dosage,‡ dichotomous§ | < 50 × 109 CFUs: 3 ≥ 50 × 109 CFUs: 6 |

0.18 (0.03 to 0.67) 0.27 (0.07 to 0.68) |

0.4 (-1.5 to 2.3) | 0.68 |

| Support from manufacturer | No: 4 Yes: 6 |

0.21 (0.02 to 0.67) 0.26 (0.07 to 0.65) |

0.16 (-1.3 to 2.9) | 0.60 |

| Proportion of cases of CDAD in placebo group, dichotomous¶ | < 6%: 5 ≥ 6%: 5 |

0.46 (0.12 to 1.05) 0.17 (0.05 to 0.41) |

-1.0 (-2.4 to 0.5) | 0.08 |

| Proportion of cases of CDAD in placebo group, continuous | - | - | -3.2 (-11.5 to 7.6) | 0.21 |

| Probiotic dosage,‡ continuous** | - | - | 0.06 (-0.02 to 0.06) | 0.81 |

Note: CDAD = Clostridium-difficile-associated diarrhea, CFU = colony-forming unit, CrI = credible interval, RR = risk ratio.

*Subgroup listed first was the control group for the comparison, e.g., P (RR in studies of quality A > studies of quality B or C) = 0.7

†p values (regression coefficient > 0) close to 0 or 1 indicate a strong association between the risk ratio and the covariate.

‡For studies that used a mixture of different types of Lactobacillus probiotics, we estimated the average dosage assuming all types of probiotics were in equal proportions.

§Missing for 1 study (Heimburger and colleagues31).

¶Used to represent population risk (in inpatients given antibiotics) for development of C. difficile-associated diarrhea.

**One outlying study (Selinger and colleagues25) was omitted because the extremely high dosage reported resulted in model convergence problems.

The pooled RR was 0.17 and was statistically significant in the studies in which the observed risk of C. difficile-associated diarrhea was 6% or greater. In comparison, the pooled RR was 0.46, with a wide CrI including 1, for the studies with an observed risk of C. difficile-associated diarrhea of less than 6%. When we repeated the meta-analysis with the risk difference as the effect size of interest, the pooled risk difference was much larger, at -0.16 (95% CrI -0.68 to 0.04), for the studies in which the observed risk of C. difficile-associated diarrhea was 6% or greater, compared with -0.02 (95% CrI -0.21 to 0.01) for those with an observed risk of less than 6%.

Sensitivity analyses

The pooled RR from the Bayesian meta-analysis was robust to changes in the prior distribution for the between-study variance (Appendix 1, Supplementary Table 1). The width of the prediction interval increased but did not affect our inferences. Similarly, other sensitivity analyses also showed that the pooled RR estimate was robust. There was no impact on our inferences of excluding the study by Gao and colleagues,20 in which the risk of C. difficile-associated diarrhea was high in the placebo group, limiting the analysis to the 5 studies that used a stricter definition of diarrhea or inclusion of the 2 studies that did not have complete results on testing.

Quality of evidence

The rating of the quality of evidence in accordance with the GRADE guidelines for RCTs is summarized in Table 5. We rated concerns about inconsistency and imprecision as "very serious" and concerns about risk of bias and indirectness as "serious." The remaining domains were rated as Unclear. We considered that the overall quality of evidence regarding the association between Lactobacillus probiotic treatment and risk of C. difficile-associated diarrhea was "very low."

Table 5: GRADE (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation)23 rating of confidence in the evidence of the 10 RCTs with 4841 participants.

| Summary of findings for primary outcome (CDAD) | Rating* | Overall quality | Comments | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median RR (95% CrI)(prediction interval) | Absolute risk | ||||

| Median (range) risk for CDAD in placebo group across studies | Expected risk for CDAD in probiotics group (95% CrI) (prediction interval) | ||||

| 0.25 (0.08 to 0.47) (0.02 to 1.34) |

6 per 100 patients (0 to 24) |

1.5 per 100 patients (0.5 to 3) (0.1 to 8.0) |

Very low | Apparently strong beneficial effect, with median RR = 0.25, but surrounded by wide prediction interval owing to heterogeneity of effect between studies | |

| Quality assessment domain | |||||

| Risk of bias | +++ | 6 studies had B or C rating (see Appendix 1) | |||

| Inconsistency | ++ | Wide range of risk for CDAD in placebo group. Wide prediction interval and wide interval around I2 statistic. Small number of cases of CDAD overall reduces credibility of results. | |||

| Indirectness | +++ | Although Lactobacillus probiotics were used in all studies, there was variation in strain and dosage used. Varying definitions of outcome across studies. | |||

| Imprecision | ++ | Small sample in several studies as CDAD was typically the secondary outcome. Few cases of CDAD in most studies. | |||

| Publication bias | Unclear | 6 studies were industry funded. The funnel plot (Figure 4), although based on few studies, suggested no asymmetry in scatter of points. | |||

| Large effect | Unclear | Although pooled estimate suggests a large effect, there remained much uncertainty in individual study estimates as reflected by wide prediction interval and credibility analysis results | |||

| Dose response | Not enough evidence | Most studies did not consider dose response | |||

| Residual confounding | Not an issue for RCTs | ||||

Note: CDAD = Clostridium-difficile-associated diarrhea, CrI = credible interval, RCT = randomized controlled trial, RR = risk ratio, SE = standard error.

*The overall quality is determined by downgrading, from a rating of "high" (4 plus signs), for any concerns in each of the first 5 domains as follows: 0 (no concerns), -1 (serious concerns) or -2 (very serious concerns), or upgrading in the case of the remaining 3 domains.

Interpretation

Our meta-analysis suggests that, on average, probiotics containing Lactobacillus spp. have a preventive effect on C. difficile-associated diarrhea, with a pooled relative risk reduction of 75%. However, the wide CrI around the predicted benefit in a future study includes an RR of 1 and reflects the presence of heterogeneity in the RRs across individual studies. Our conclusion is further supported by a Bayesian credibility analysis that suggests that the statistically significant results of the meta-analysis could be altered by use of a moderately informative skeptical prior distribution.

The observed heterogeneity could not be explained conclusively by study-level characteristics such as risk of bias, background risk of C. difficile-associated diarrhea as measured by frequency in the placebo arm, higher versus lower dosage of probiotics or financial support from industry, owing in part to the small number of studies we identified. However, there appears to be evidence suggesting that in order to observe a beneficial effect on diarrhea due to C. difficile in a single study, a high background risk of the condition is needed. This leads us to conclude that it is premature to suggest that there is a beneficial effect of Lactobacillus probiotics in all settings.

The magnitude of the pooled RR is consistent with reports from other meta-analyses of various probiotics7,8 using the standard DerSimonian-Laird method, although the earlier analyses concluded there was no between-study heterogeneity. When the number of studies is small, the DerSimonian-Laird estimate of the between-study variance is more likely to be close to 0, incorrectly leading to the conclusion that there is no between-study heterogeneity.13 When this happens, even if a user intended to fit a DerSimonian-Laird random-effects model, a fixed-effects model is obtained instead. This was the case in our meta-analysis. If the earlier meta-analyses had used a method that adjusted for between-study heterogeneity, there may have been no discrepancy between their conclusions and those of Allen and colleagues.10

As we have shown, the Bayesian approach is valuable as it improves the estimation of between-study heterogeneity compared with the DerSimonian-Laird method. Furthermore, it uses an exact approach, which is preferable when dealing with studies with small numbers of events.

The recent large RCT by Allen and colleagues10 was planned during an outbreak, and the success of other preventive measures resulted in a lower incidence of C. difficile-associated diarrhea than expected and a loss of power. Another trial was stopped early, having reached its coprimary outcome for antibiotic-associated diarrhea before any cases of C. difficile-associated diarrhea were identified.25 Thus, we see that a challenge in conducting such RCTs is to attain a sufficient number of cases of diarrhea due to C. difficile to allow estimation of the effect of probiotics.

For several decades there has been an interest in taking advantage of Bayesian statistical methods for medical research,13,40-43 particularly as software to support it is now available.15,44 As we have shown, advantages include the ability to make probabilistic statements (e.g., to estimate p [RR < 1]), to take into account the uncertainty in multiple parameters simultaneously and to consider the impact of prior information via a credibility analysis. The Bayesian approach is increasingly being used for meta-analysis as if offers improved estimation of between-study heterogeneity.

The importance of using appropriate methods for random-effects meta-analysis has been widely acknowledged45,46 and needs to be recognized by authors of checklists such as PRISMA and GRADE, who are in a position to influence good research practices for systematic reviews. As our analysis shows, the choice of statistical method could change the conclusions drawn and policies made based on the same body of evidence.

Limitations

Our strict inclusion criteria limited the number of studies included. The meta-regression for important covariates was therefore relatively insensitive on account of the small number of studies in each group. The total number of cases of C. difficile-associated diarrhea was small, with the largest number contributed by a study from China,20 which also had the highest rate of C. difficile-associated diarrhea in the placebo arm (24%, compared with 19% in a study conducted during an outbreak in Quebec hospitals28). Omitting that study, however, did not affect the effect estimate.

Other potential contributors to underdetection of cases were the insensitivity of the test used to identify C. difficile-associated diarrhea47 in earlier studies and insufficiently long follow-up in some studies, given that trials that followed patients after discharge identified additional cases.28,29 Neither of these factors is expected to contribute to a differential misclassification and thereby introduce bias. We assumed that missing tests had the same probability of having a positive result as available tests, although, if testing depended on severity of diarrhea, we may have overestimated the number of tests with a positive result. Nevertheless, our adjustment produced only slight changes to the RRs.

We chose to strictly limit our inclusion criteria to studies of Lactobacillus probiotic treatment in adults, as the exact mechanism by which probiotics act is unknown.10 Accordingly, our results are not generalizable to yeast probiotics or to pediatric populations. In addition, although unpublished abstracts37,38 were included in earlier meta-analyses,7,8 we chose not to include them, as it was impossible to verify their risk of bias. Furthermore, the long interval that had elapsed since publication of some abstracts raised concerns of bias.

Although the studies included in the meta-analysis met our inclusion criteria, they were clinically heterogeneous in factors relating to background risk of C. difficile-associated diarrhea, species and dosage of probiotic and treatment duration. As is common with studies involving complementary medicines, there was wide variation in dosage and formulation. We selected only studies in which the probiotic was a pure Lactobacillus preparation or a mixture of Lactobacillus and other species but did not restrict the dosage, on the assumption that a minimum dosage was required for colonization of the colon and that this minimum dosage was achieved in all studies. We were unable to adjust for variation in length of treatment or follow-up in our analyses as these were not measured in a uniform manner across studies.

Conclusion

Statistical heterogeneity as well as clinical heterogeneity reduces our confidence in the evidence favouring treatment with probiotics containing Lactobacillus spp. for reducing the risk of C. difficile infection in patients receiving antibiotics. Future research will need to take account of the changing epidemiologic features of C. difficile infection, with reduced incidence in hospital settings where active prevention measures have been taken. Studies in high-risk settings that can yield a large number of cases of C. difficile-associated diarrhea are needed to provide conclusive results.

Supplemental information

For reviewer comments and the original submission of this manuscript, please see www.cmajopen.ca/content/4/4/E706/suppl/DC1

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Gilca R, Hubert B, Fortin E, et al. Epidemiological patterns and hospital characteristics associated with increased incidence of Clostridium difficile infection in Quebec, Canada, 1998-2006. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2010;31:939–47. doi: 10.1086/655463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Loo VG, Poirier L, Miller MA, et al. A predominantly clonal multi-institutional outbreak of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea with high morbidity and mortality. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2442–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barbut F, Petit JC. Epidemiology of Clostridium difficile-associated infections. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2001;7:405–10. doi: 10.1046/j.1198-743x.2001.00289.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown KA, Khanafer N, Daneman N, et al. Meta-analysis of antibiotics and the risk of community-associated Clostridium difficile infection. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57:2326–32. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02176-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Nood E, Vrieze A, Nieuwdorp M, et al. Duodenal infusion of donor feces for recurrent Clostridium difficile. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:407–15. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1205037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goldenberg JZ, Ma SS, Saxton JD, et al. Probiotics for the prevention of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea in adults and children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;5):CD006095. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006095.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnson S, Maziade PJ, McFarland LV, et al. Is primary prevention of Clostridium difficile infection possible with specific probiotics? Int J Infect Dis. 2012;16:e786–92. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2012.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnston BC, Ma SS, Goldenberg JZ, et al. Probiotics for the prevention of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157:878–88. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-157-12-201212180-00563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lau CS, Chamberlain RS. Probiotics are effective at preventing Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Gen Med. 2016;9:27–37. doi: 10.2147/IJGM.S98280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Allen SJ, Wareham K, Wang D, et al. Lactobacilli and bifidobacteria in the prevention of antibiotic-associated diarrhoea and Clostridium difficile diarrhoea in older inpatients (PLACIDE): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial. Lancet. 2013;382:1249–57. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61218-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Higgins JP, Spiegelhalter DJ. Being sceptical about meta-analyses: a Bayesian perspective on magnesium trials in myocardial infarction. Int J Epidemiol. 2002;31:96–104. doi: 10.1093/ije/31.1.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Version 5.1.0. Oxford (UK): Cochrane Collaboration; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cornell JE, Mulrow CD, Localio R, et al. Random-effects meta-analysis of inconsistent effects: a time for change. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160:267–70. doi: 10.7326/M13-2886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:264–9. W64. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Warn DE, Thompson SG, Spiegelhalter DJ. Bayesian random effects meta-analysis of trials with binary outcomes: methods for the absolute risk difference and relative risk scales. Stat Med. 2002;21:1601–23. doi: 10.1002/sim.1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21:1539–58. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matthews RAJ. Methods for assessing the credibility of clinical trial outcomes. Drug Inf J. 2001;35:1469–78. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spiegelhalter DJ, Abrams KR, Myles JP. Bayesian approaches to clinical trials and health-care evaluation. New York: John Wiley and Sons; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arends LR, Hoes AW, Lubsen J, et al. Baseline risk as predictor of treatment benefit: three clinical meta-re-analyses. Stat Med. 2000;19:3497–518. doi: 10.1002/1097-0258(20001230)19:24<3497::aid-sim830>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gao XW, Mubasher M, Fang CY, et al. Dose-response efficacy of a proprietary probiotic formula of Lactobacillus acidophilus CL1285 and Lactobacillus casei LBC80R for antibiotic-associated diarrhea and Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea prophylaxis in adult patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:1636–41. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lunn DJ, Thomas A, Best N, et al. WinBUGS - a Bayesian modelling framework: concepts, structure, and extensibility. Stat Comput. 2000;10:325–37. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Viechtbauer W. Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor package. J Stat Softw. 2010;36:1–48. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Balshem H, Helfand M, Schunemann HJ, et al. GRADE guidelines: 3. Rating the quality of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64:401–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ouwehand AC, DongLian C, Weijian X, et al. Probiotics reduce symptoms of antibiotic use in a hospital setting: a randomized dose response study. Vaccine. 2014;32:458–63. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.11.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Selinger CP, Bell A, Cairns A, et al. Probiotic VSL#3 prevents antibiotic-associated diarrhoea in a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. J Hosp Infect. 2013;84:159–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2013.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sampalis J, Psaradellis E, Rampakakis E. Efficacy of BIO K+ CL1285 in the reduction of antibiotic-associated diarrhea - a placebo controlled double-blind randomized, multi-center study. . Arch Med Sci. 2010;6:56–64. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2010.13508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Safdar N, Barigala R, Said A, et al. Feasibility and tolerability of probiotics for prevention of antibiotic-associated diarrhoea in hospitalized US military veterans. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2008;33:663–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2710.2008.00980.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beausoleil M, Fortier N, Guenette S, et al. Effect of a fermented milk combining Lactobacillus acidophilus Cl1285 and Lactobacillus casei in the prevention of antibiotic-associated diarrhea: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Can J Gastroenterol. 2007;21:732–6. doi: 10.1155/2007/720205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hickson M, D'Souza AL, Muthu N, et al. Use of probiotic Lactobacillus preparation to prevent diarrhoea associated with antibiotics: randomised double blind placebo controlled trial. BMJ. 2007;335:80. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39231.599815.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Plummer S, Weaver MA, Harris JC, et al. Clostridium difficile pilot study: effects of probiotic supplementation on the incidence of C. difficile diarrhoea. Int Microbiol. 2004;7:59–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Heimburger DC, Sockwell DG, Geels WJ. Diarrhea with enteral feeding: prospective reappraisal of putative causes. Nutrition. 1994;10:392–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thomas MR, Litin SC, Osmon DR, et al. Lack of effect of Lactobacillus GG on antibiotic-associated diarrhea: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Mayo Clin Proc. 2001;76:883–9. doi: 10.4065/76.9.883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wenus C, Goll R, Loken EB, et al. Prevention of antibiotic-associated diarrhoea by a fermented probiotic milk drink. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2008;62:299–301. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lönnermark E, Friman V, Lappas G, et al. Intake of Lactobacillus plantarum reduces certain gastrointestinal symptoms during treatment with antibiotics. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;44:106–12. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3181b2683f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wullt M, Hagslatt ML, Odenholt I. Lactobacillus plantarum 299v for the treatment of recurrent Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhoea: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Scand J Infect Dis. 2003;35:365–7. doi: 10.1080/00365540310010985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wong S, Jamous A, O'Driscoll J, et al. A Lactobacillus casei Shirota probiotic drink reduces antibiotic-associated diarrhoea in patients with spinal cord injuries: a randomised controlled trial. Br J Nutr. 2014;111:672–8. doi: 10.1017/S0007114513002973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rafiq R, Pandey D, Osman SM, et al. Prevention of Clostridium difficile (C. difficile) diarrhea with probiotic in hospitalized patients treated with antibiotics [abstract]. Gastroenterology. 2007;132(Suppl 2):A187. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Eastmond J, Miller M, Florencio S, et al. Results of 2 prospective randomized studies of Lactobacillus GG to prevent C. difficile infection in hospitalized adults receiving antibiotics [abstract K-4200]. In: Abstracts of the 48th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, 2008 Oct. 25-28. Washington (DC): American Society of Microbiology; 2008:578-9. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ioannidis JP, Trikalinos TA. The appropriateness of asymmetry tests for publication bias in meta-analyses: a large survey. CMAJ. 2007;176:1091–6. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.060410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Goodman SN. Toward evidence-based medical statistics. 2: The Bayes factor. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130:1005–13. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-130-12-199906150-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brophy JM. Multicenter trials, guidelines, and uncertainties: Do we know as much as we think we do? Int J Cardiol. 2015;187:600–3. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brophy JM, Joseph L. Placing trials in context using Bayesian analysis. GUSTO revisited by Reverend Bayes. JAMA. 1995;273:871–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Spiegelhalter DJ, Myles JP, Jones DR, et al. Bayesian methods in health technology assessment: a review. Health Technol Assess. 2000;4:1–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dias S, Welton NJ, Sutton AJ, et al. Evidence synthesis for decision making 1: introduction. Med Decis Making. 2013;33:597–606. doi: 10.1177/0272989X13487604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Spiegelhalter DJ. A re-evaluation of random-effects meta-analysis. J R Stat Soc Ser A Stat Soc. 2009;172:137–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-985X.2008.00552.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cornell JE, Mulrow CD, Localio R, et al. Random-effects meta-analysis of inconsistent effects: a time for change. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160:267–70. doi: 10.7326/M13-2886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brecher SM, Novak-Weekley SM, Nagy E. Laboratory diagnosis of Clostridium difficile infections: there is light at the end of the colon. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;57:1175–81. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.