Abstract

A 23-year-old asymptomatic woman was referred to our hospital for further examination of a systolic ejection murmur with fixed splitting of the second heart sound auscultated at the third left sternal border. Initial echocardiography could not detect the cause. Subsequently performed low-dose computed tomography, however, ruled out the possibility of any congenital heart diseases, but revealed a markedly shortened anteroposterior diameter of the chest, which led us to a diagnosis of straight back syndrome. A vertically oriented “pancake” appearance of the heart, straight vertebral column, and compression of the right ventricular outflow tract were clearly demonstrated on the reconstructed images.

Keywords: straight back syndrome, right ventricular outflow tract, dual-source computed tomography, atrial septal defect

Introduction

Straight back syndrome has been reported to be a “pseudo-heart disease” that can mimic congenital abnormalities, especially atrial septal defect (ASD) (1). However, three-dimensional anatomical recognition of this rare disease entity appears to be insufficient. In this case report, we demonstrate the detailed anatomical background of straight back syndrome with a series of images obtained from low-dose dual-source computed tomography (DSCT).

Case Report

A 23-year-old asymptomatic woman was referred to our hospital for a detailed examination of a systolic ejection murmur with fixed splitting of the second heart sound auscultated at the third left sternal border. Electrocardiography showed right axis deviation and an incomplete right bundle branch block. According to these findings, the patient was suspected of having left-to-right shunt disease, including ASD. Contrary to expectations, transthoracic echocardiography did not indicate ASD, but instead only showed the presence of trivial mitral valve regurgitation due to anterior mitral valve prolapse.

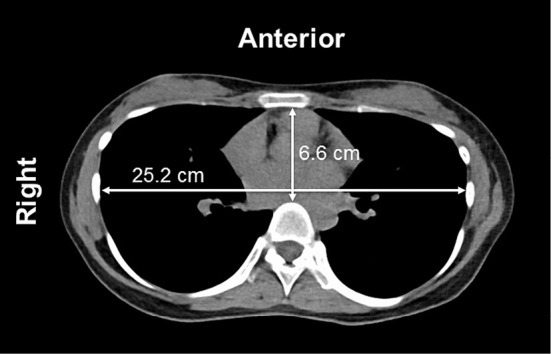

Transesophageal echocardiography performed at our institution also ruled out the existence of ASD. Because the four pulmonary veins could not be adequately visualized, she underwent low-dose electrocardiogram-gated contrast-enhanced cardiac computed tomography (CT) using commercially available third-generation DSCT (SOMATOM Force, Siemens Healthcare, Forchheim, Germany) for further differential diagnosis, including partial anomalous pulmonary venous return, unroofed coronary sinus, subvalvular pulmonary stenosis, and double-chambered right ventricle. A low-dose protocol (acquisition mode, high-pitch dual spiral scan; tube voltage, 70 kVp; rotation time, 250 ms; effective radiation dose, around 1 mSv) was performed with a contrast agent volume of only 20 mL. The DSCT findings ruled out the possibility of any congenital heart diseases, whereas the axial images clearly showed a markedly shortened anteroposterior diameter of the chest (Fig. 1), which led us to a diagnosis of straight back syndrome. A vertically oriented “pancake” appearance (a compressed heart that appears to be enlarged in frontal images) of the heart (1) located in the so-called Valentine position (the heart positioned on its apex) (2) (Fig. 2A), straight vertebral column (Fig. 2B), and compression of the entire right ventricular outflow tract (RVOT) (Figure 3, 4) were clearly demonstrated on the reconstructed images. The anteroposterior diameter of the RVOT measured using DSCT was 11.6 mm in systole. All image reconstructions were performed using a commercially available workstation (Ziostation ver. 2.1.7.1.; Ziosoft Inc., Tokyo, Japan). An accelerated flow in the compressed RVOT was confirmed with subsequently re-examined transthoracic echocardiography. The anteroposterior diameter of the RVOT measured with echocardiography was 9.2 mm in systole. Compression of the RVOT and the accelerated flow were compatible findings as the cause of her systolic ejection murmur with fixed splitting of the second heart sound.

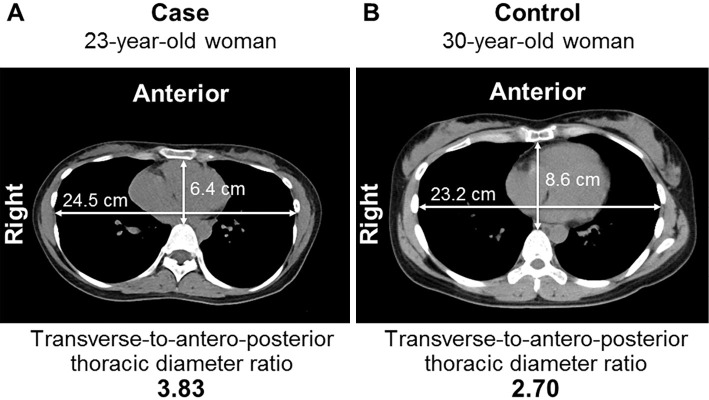

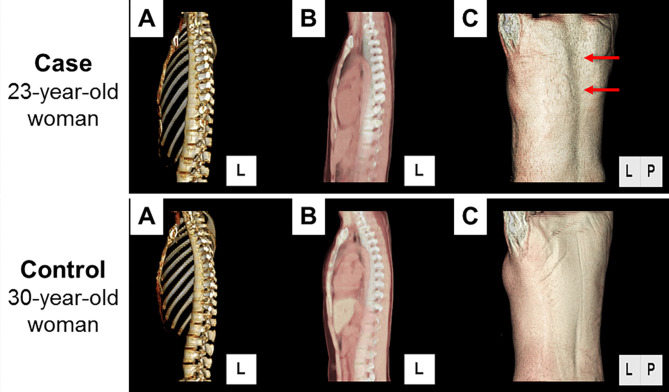

Figure 1.

Plain axial image of the thoracic cage. Axial image showing thoracic cage compression observed as a shortening of the anteroposterior diameter of the chest. The ratio of transverse-to-anteroposterior diameter is 3.82.

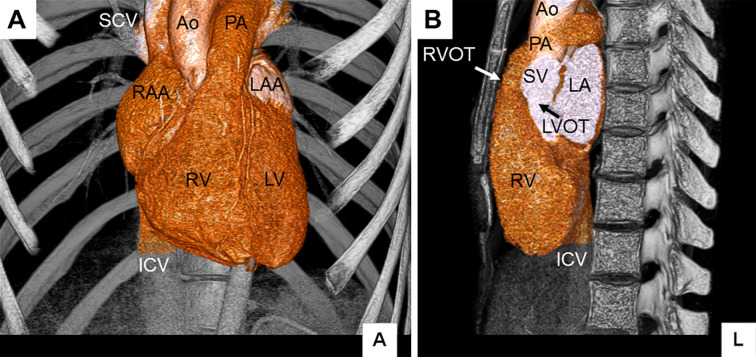

Figure 2.

Volume-rendered images of the thoracic cage. A vertically oriented “pancake” appearance of the heart (A) and a straight vertebral column (B) are shown. Ao: ascending aorta, ICV: inferior caval vein, LA: left atrium, LAA: left atrial appendage, LV: left ventricle, LVOT: left ventricular outflow tract, PA: pulmonary artery, RAA: right atrial appendage, RV: right ventricle, RVOT: right ventricular outflow tract, SCV: superior caval vein, SV: sinus of Valsalva

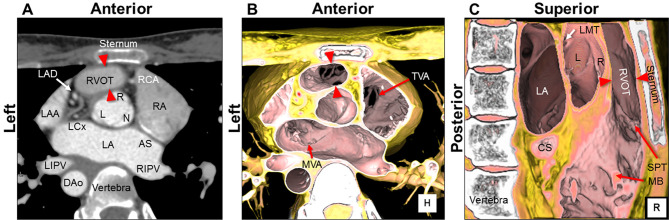

Figure 3.

Compression of the right ventricular outflow tract: Virtual dissection images. Compression of the entire right ventricular outflow tract (RVOT) between the aortic root and sternum are shown in the multiplanar reconstruction image (A) and volume-rendered image viewed from the cranial (B) and right (C) directions. The sectional plane of panel A is on the same level as that of panel B. The anteroposterior diameter (red arrowheads) of the RVOT is 11.6 mm in systole. AS: atrial septum, CS: coronary sinus, DAo: descending aorta, L: left coronary aortic sinus, LA: left atrium, LAA: left atrial appendage, LAD: left anterior descending artery, LCx: left circumflex artery, LIPV: left inferior pulmonary vein, LMT: left main trunk, MB: moderator band, MVA: mitral valvular attachment, N: non-adjacent aortic sinus, R: right coronary aortic sinus, RA: right atrium, RCA: right coronary artery, RIPV: right inferior pulmonary vein, SPT: septoparietal trabecula, TVA: tricuspid valvular attachment

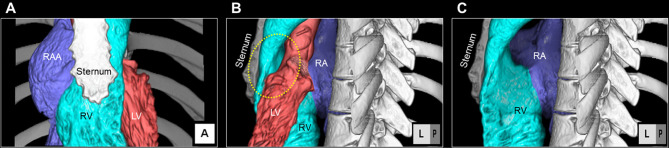

Figure 4.

Compression of the right ventricular outflow tract: Dye-cast images. The relationship between the sternum and right ventricular outflow tract is shown in the frontal image (A). Viewed from the left posterior oblique 120°, the three-dimensional aspect of the entirely compressed right ventricular outflow tract (yellow dotted circle) between the sternum and aortic root is observed (B). The ascending aorta, aortic root, and left ventricle are removed from panel B (C). Note the aortic “imprint” on the posterior right ventricular outflow tract. LV: left ventricle, RA: right atrium, RAA: right atrial appendage, RV: right ventricle

Discussion

Straight back syndrome has been reported to be a “pseudo-heart disease” that can mimic congenital abnormalities, especially ASD (1,3). It typically occurs in young, thin persons with a reduced anteroposterior diameter of the chest because of a straight thoracic vertebral column caused by the absence of normal thoracic kyphosis. Exaggerated splitting of the second heart sound and an incomplete right bundle branch block are common associated findings with ASD (1,3). Although the systolic ejection murmur, often heard at the left sternal border, originates due to RVOT compression, this murmur lacks the typical Rivero-Carvallo sign. Rather, this murmur decreases on deep inspiration and increases on deep expiration (3), because deep inspiration enlarges the thoracic cage and releases compression of the RVOT. Systolic clicks are occasionally audible because of complicated mitral valve prolapse.

Datey et al. reported that the average transverse-to-anteroposterior thoracic diameter ratio of patients with straight back syndrome is 3.80, which is compatible with the present case (Figure 1, 5), whereas that of the normal group is 2.17 (4).

Figure 5.

Comparison of axial images of the present case with those of the control case. Axial images at the level of the ninth thoracic vertebra showing a more flattened chest in the present case (A) than that in the control case (B).

The difference in the anteroposterior diameter of the RVOT measured using DSCT and echocardiography could be explained by the differences in the respiratory phase of image data acquisition; the DSCT scan was obtained on deep inspiration in systole, whereas the echocardiographic image was obtained on deep expiration and measured in systole. Figure 5, 6 show a comparison of the present case with a control case of a 30-year-old woman.

Figure 6.

Comparison of volume-rendered images of the present case with those of the control case. Volume-rendered thoracic images revealing a straight thoracic vertebra due to the absence of normal thoracic kyphosis (A), narrowed thoracic cages (A, B), a compressed heart (B), and a vertical median recess (red arrows) at the back between the scapulae (C).

Within the pericardial space, the posterior surface of the heart is firmly fixed by the vessels and pericardial reflections (5). Therefore, compared with the posterior part, the anterior to apical part of the heart is relatively easy to rotate. A considerable proportion of patients with pectus excavatum present with right atrial and ventricular compression due to narrowing of the anteroposterior diameter of the chest (6). However, compression of the RVOT with a systolic ejection murmur and accentuated splitting of the second heart sound appears to be less common than straight back syndrome. The frequently observed leftward cardiac displacement in pectus excavatum (7) can explain why the RVOT can escape from squeezing. Although it remains a speculation, in pectus excavatum, the negatively bulged anterior chest wall may allow the heart to be displaced, often toward the left side (7). On the other hand, the relatively flat anterior chest wall in straight back syndrome may completely prevent the displacement of the heart, as observed in the present case. Regardless, in both anatomical situations, whether the RVOT can escape from considerable compression is relevant.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first three-dimensional image of straight back syndrome reconstructed using low-dose DSCT. As demonstrated, low-dose DSCT with minimal contrast volume could comprehensively visualize the detailed anatomical background of this rare disease entity. The reconstructed images help identify the morphology of the heart and thorax in straight back syndrome and reinforce the importance of upper body inspection (including the superior dorsal region), careful auscultation, and lateral chest radiography in young patients who present with clinical findings suggesting ASD.

The authors state that they have no Conflict of Interest (COI).

Acknowledgement

The authors thank the following radiological technologists for their support in image acquisition and processing: Tomoki Maebayashi, Erina Suehiro, Wakiko Tani, Toshinori Sekitani, Kiyosumi Kagawa, Noriyuki Negi, Tohru Murakami, and Hideaki Kawamitsu.

References

- 1.Deleon AC Jr, Perloff JK, Twigg H, Majd M. The straight back syndrome: clinical cardiovascular manifestations. Circulation 32: 193-203, 1965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson RH, Razavi R, Taylor AM. Cardiac anatomy revisited. J Anat 205: 159-177, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Esser SM, Monroe MH, Littmann L. Straight back syndrome. Eur Heart J 30: 1752, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Datey KK, Deshmukh MM, Engineer SD, Dalvi CP. Straight back syndrome. Br Heart J 26: 614-619, 1964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lachman N, Syed FF, Habib A, et al. Correlative anatomy for the electrophysiologist, Part I: the pericardial space, oblique sinus, transverse sinus. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 21: 1421-1426, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kelly RE., Jr Pectus excavatum: historical background, clinical picture, preoperative evaluation and criteria for operation. Semin Pediatr Surg 17: 181-193, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oezcan S, Attenhofer Jost CH, Pfyffer M, et al. Pectus excavatum: echocardiography and cardiac MRI reveal frequent pericardial effusion and right-sided heart anomalies. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 13: 673-679, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]