Abstract

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is an important pathogen in opportunistic infections in humans. The increased incidence of antimicrobial-resistant P. aeruginosa isolates has highlighted the need for novel and more potent therapies against this microorganism. Annona glabra is known for presenting different compounds with diverse biological activities, such as anti-tumor and immunomodulatory activities. Although other species of the family display antimicrobial actions, this has not yet been reported for A. glabra. Here, we investigated the antimicrobial activity of the ethyl acetate fraction (EAF) obtained from the leaf hydroalcoholic extract of A. glabra. EAF was bactericidal against different strains of P. aeruginosa. EAF also presented with a time- and concentration-dependent effect on P. aeruginosa viability. Testing of different EAF sub-fractions showed that the sub-fraction 32-33 (SF32-33) was the most effective against P. aeruginosa. Analysis of the chemical constituents of SF32-33 demonstrated a high content of flavonoids. Incubation of this active sub-fraction with P. aeruginosa ATCC 27983 triggered an endothermic reaction, which was accompanied by an increased electric charge, suggesting a high binding of SF32-33 compounds to bacterial cell walls. Collectively, our results suggest that A. glabra-derived compounds, especially flavonoids, may be useful for treating infections caused by P. aeruginosa.

Keywords: Annona glabra Pseudomonas aeruginosa, antimicrobial activity, flavonoids

Introduction

Infection by Pseudomonas aeruginosa, a Gram-negative bacterium known to cause a variety of opportunistic infections in humans, can result in pneumonia, sepsis, meningitis, and urinary tract infections, as well as skin and soft-tissue infections (Wroblewska, 2006). The increasing prevalence of P. aeruginosa isolates that are resistant to almost all antimicrobials has raised concern among public health authorities in recent decades and highlights the importance of developing novel antimicrobial drugs active against this pathogen (Porras-Gomez et al., 2012). The development of resistance in P. aeruginosa is considered multifactorial, with mutations in several genes that encode efflux pumps, porins, penicillin-binding proteins, and chromosomal β-lactamases (Poole, 2011; Morita et al., 2014). All of these genes are involved in the resistance to distinct antibiotic classes, including penicillins, carbapenems, aminoglycosides, and fluoroquinolones (Ozer et al., 2009).

Natural compounds have been extensively studied as potential sources of antimicrobial compounds. Indeed, different natural compounds were suggested as antimicrobials against P. aeruginosa (Hayashi et al., 2014; Yang et al., 2015; Undabarrena et al., 2016); with some of them acting as efflux pump inhibitors in P. aeruginosa, thus contributing to reversal of resistance in these strains (Morita et al., 2016).

Annona glabra Linn is a tropical fruit tree native to Florida (United States of America), the Caribbean, and Central and South Americas. It has a wide distribution in Brazil, mainly in mangrove areas (Núñez-Elisea et al., 1999). Annona glabra is a potential source of compounds for cancer therapy, where an alcoholic seed extract has shown anticancer activity (Cochrane et al., 2008). In addition, a preliminary screening also demonstrated substantial antimicrobial activities for the hexane extract of A. glabra stem bark (Padmaja et al., 1995).

Antimicrobial activity was recently reported in other Annona species. The hexane and chloroform fractions obtained from Annona vepretorum leaves display antimicrobial activity against Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Staphylococcus aureus (Almeida et al., 2014). Additionally, Rinaldi and collaborators showed that the methanol, dichloromethane, and ethyl acetate fractions (EAFs) obtained from Annona hypoglauca stems inhibited the growth of Staphylococcus aureus and Enterococcus faecalis (Rinaldi et al., 2016).

Different compounds may confer antimicrobial properties for plants, with flavonoids being one of the major compounds to which these effects have been attributed. To date, compounds, such as annoglabayin and methyl-16 alpha-hydro-19-al-ent-kauran-17-oate (kaurane diterpenoids; Chen et al., 2004; Zhang et al., 2004) and squamosamides (Bao et al., 2015), have been identified and isolated from A. glabra fruits. However, little is known regarding the flavonoid content in this plant or their ability to function as antimicrobials.

Herein, we evaluated the antibacterial effects of the hydroalcoholic extract from A. glabra leaves against standard and clinical isolates of P. aeruginosa and characterized the antibacterial effects of the EAF. Additionally, the interactions between a flavonoid-rich sub-fraction (SF) of EAF (SF32-33) and P. aeruginosa was investigated by characterization of changes in the zeta potential (ZP) and enthalpy.

Materials and Methods

Plant

The stems, leaves, and fruits of Annona glabra Linn (Arecaceae) were collected at “Central do Maranhão,” Maranhão, Brazil (2°16′20.2′′ S, 44° 57′14.2′′ W). A voucher specimen (N° 01077) was deposited in the herbarium Ático Seabra of the Federal University of Maranhão, São Luís, Brazil.

Preparation of Extracts from Leaves

Collected leaves were washed in running water for up to 5 min before being dried at room temperature. The dried leaves were triturated using a blender (Siemsen, model LI-1.5, São Paulo, Brazil) for 20 min to obtain a fine powder, and 300 g were extracted twice with 1000 ml ethyl alcohol (99.5%; Sigma–Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) at room temperature, with a 5 days period between extractions. The mixture was filtered through cellulose filter paper (Whatman No. 4, GE Healthcare UK, Amersham, UK) and evaporated to dryness under reduced pressure using a rotary evaporator (Eyela N-1200BV-W, Tokyo, Japan) at 40°C. The residual solvent was removed in a vacuum centrifuge at 40°C to yield crude ethanol extracts of leaves.

Preparation of the EAF from the Leaf Hydroalcoholic Extract of A. glabra

The EAF was obtained from the leaf hydroalcoholic extract of A. glabra as previously described (de Siqueira et al., 2014). For this, six grams of the ethanol extract were suspended in MeOH:H2O (4:1) using an ultrasonic bath (Elmasonic® E 30H Elma, Sigen, Germany) and extracted successively by solvent-solvent partitioning. For concentration and mass determination, 10 ml of EAF was dried in a Speedvac system (Speed Vac Concentrator Sc110, Savant, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) at 50°C for 60 h. For in vitro assays, EAF and SF stock solutions were prepared in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; Sigma–Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) at 50 mg/ml.

Procedure for Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC)

Ethyl acetate fraction SFs were obtained by GPC. For this, 3.15 g/ml of EAF was injected into GPC glass columns (Büchi column n° 17980), packaged with Sephadex LH-20 TM gel (GE Healthcare, USA), and eluted in 2 ml of 99% methanol (P.A., Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). For the mobile phase, the eluate was pumped at a flow rate of 480 ml/h, for 4 h and two hundred fractions were then collected (20 ml/tube).

Thin Layer Chromatography (TLC) Analysis

Ethyl acetate fraction SFs were characterized by TLC analysis on pre-coated commercial silica gel plates G-60/F254 (0.25 mm, Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). Briefly, TLC plates were eluted using solvent mixtures in different proportions: (i) ethyl acetate:methanol:water (EtOAc:MeOH:H2O/80:11:5 v/v) for polar compounds or (ii) dichloromethane:methanol (DCM:MeOH/95:5 v/v) for non-polar compounds. High content flavonoid blottings were visualized under UV light at 360 nm after spraying the plates with a mixture (1:1) of an ethanol solution containing vanillin 1% w/v and sulfuric acid at 10% (v/v) or 2-aminoethyl diphenylborinate/polyethylene glycol 4000 (NP/PEG) solution in ethanol at 2% (w/v; de Siqueira et al., 2014). Sub-fractions with similar blotting profiles were pooled and analyzed in microbiological assays [Minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC) and Minimum bactericidal concentrations (MBC)].

Liquid Chromatography-High Resolution Mass Spectrometry (LC-HRMS) Analysis

The LC-HRMS (MSMS) analysis of the flavonoid-rich SF SF32-33 was performed on a Nexera UHPLC system (Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan) hyphenated to a maXis ETD high resolution ESI-QTOF (ElectroSpray Ionization – Quadrupole Time of Flight) mass spectrometer (Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany) and controlled by the Compass 1.5 software package (Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany), according to a previously described method (de Siqueira et al., 2014). For analysis, SF32-33 (10 μg/ml) was dissolved in ACN:H2O (1:1 v/v) and injected into a Shimadzu Shim-Pack XR-ODS-III column (C18, 2.2 μm, 80 Å, 2.0 mm × 200 mm) at a flow rate of 200 μL/min. SF32-33 was then sequentially eluted with mixtures of water containing 0.1% formic acid (Solution A), followed by acetonitrile solution containing 0.1% formic acid (Solution B). For the application of Solution B, 10% was applied over a 10-min period, followed by a linear gradient (10–100%) for 40 min, and finally 100% for 5 min. Ion-source parameters were set to 500 V for end plate offset, 4500 V for capillary voltage, 2.0 bar nebulizer pressure, and 8.0 l/min dry gas flow at 200°C. Data-dependent precursor fragmentation was performed at collision energies of 30 eV. Ion cooler settings were optimized for an average sensitivity of 40–1000 m/z range using a solution of 10 mM sodium formate in 2-propanol/0.2% formic acid (1:1, v/v) as the calibration solution. Mass calibration was achieved by initial ion-source infusion of 20 μl calibration solution and post-acquisition recalibration of the raw data. Compound identification was performed by chromatographic peak dissection, with subsequent formula determination according to exact mass and isotope pattern (MS1) and database comparison of compound fragment spectra (MS2), as well as the comparison of compound fragment spectra and co-elution with standard compounds (Sigma–Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). Sources of reference ESI fragmentation pattern spectra consisted of an in-house database of commercial or isolated and identified compounds, as well as the public spectra database MassBank (Horai et al., 2010).

Antimicrobial Activity Assays

Antibacterial activity assays were evaluated using the following microorganisms: P. aeruginosa ATCC 27983 (kindly donated by the Instituto Nacional de Controle de Qualidade em Saúde – da Função Instituto Osvaldo Cruz, INCQS–FIOCRUZ, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil) and 10 multi-resistant P. aeruginosa clinical strains from the culture collection of the laboratory (Table 1, first column). Minimum inhibitory concentrations were determined using the broth microdilution method, as described in CLSI M07-A10 (CLSI, 2015), with minor modifications. For this, different concentrations of EAF or SF32-33 (0.05–1024 μg/ml) were incubated with 100 μl of Mueller–Hinton broth (MHB, Difco, Detroit, MI, USA) in 96-well plates. Vehicle (1% DMSO)-treated wells were used as negative controls. Then, a bacterial inoculum (5 × 105 CFU/mL) was added into the wells. Sterility controls were included for each assay, and tests were performed on three occasions in triplicate. Ciprofloxacin-treated wells (Sigma–Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) were used as positive controls (0.05–1024 μg/ml). The microdilution plates were incubated under aerobic conditions at 35°C for 24 h. The MIC was defined as the lowest concentration of EAF or SF32-33 that completely inhibited the visible growth of microorganisms.

Table 1.

Antimicrobial activity of the leaf hydroalcoholic extract and the ethyl acetate fraction (EAF) of Annona glabra on Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains.

| Bacterial strains | Concentration (μg/ml) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Hydroalcoholic extract |

EAF |

|||

| MIC | MBC | MIC | MBC | |

| ATCC 27853 | 1024 | 2048 | 8 | 16 |

| P1C | 1024 | 2048 | 8 | 16 |

| P2C | 1024 | 2048 | 8 | 16 |

| P5C | 1024 | 2048 | 8 | 16 |

| P18C | 1024 | 2048 | 8 | 16 |

| P27C | 1024 | 2048 | 8 | 16 |

| P32C | 1024 | 2048 | 4 | 4 |

| P110c | 1024 | 2048 | 8 | 16 |

| P113C | 1024 | 2048 | 8 | 16 |

| P146C | 1024 | 1024 | 4 | 8 |

| P165C | 1024 | 2048 | 8 | 16 |

Minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC) and minimum bactericidal concentrations (MBC) were calculated and expressed in μg/ml. Assays were performed in duplicate on three different experiments.

Minimum bactericidal concentrations were evaluated soon after determining the MIC. For this, 100 μl of culture medium was removed from each well with no visible growth and transferred to Mueller–Hinton agar plates. Plates were then incubated at 35°C for 24 h. The MBC was considered as the lowest concentration that either totally prevented growth or resulted in a ≥99.9% decrease in the initial inoculum (i.e., a 3 log10 reduction in CFU/ml) upon subculture. Bacteriostatic action was defined as a ratio of MBC to MIC that is >4. Otherwise, a lower MBC to MIC ratio was defined as bactericidal action (Pankey and Sabath, 2004). All tests were performed in triplicate.

Time-Kill Assays

The time-dependent effects of SF32-33 on P. aeruginosa viability were evaluated by measuring the reduction in the numbers of CFU per milliliter for 3–24 h. Briefly, SF32-33 (2.0–64 μg/ml) was added to each well and incubated with 104 CFU/ml of P. aeruginosa ATCC 27983 for 3–24 h at 35°C. A 100-μl aliquot of bacterial inoculum was removed from the microtiter plates containing SF32-33 at different intervals until 24 h, and were serially diluted in sterile saline, before plating onto MacConkey agar (BBLTM MacConkey Agar, BD, Sparks, MD, USA) plates for colony count determinations. The plates were incubated at 35°C for 24 h prior to colony counting. The results were expressed as the percentage of P. aeruginosa in relation to the negative control wells (vehicle-treated) for each time analyzed. The data represent the mean values of three independent experiments in duplicate assays. Vehicle-treated wells were used as controls.

Effect of Flavonoids on Zeta Potential of Bacterial Cell Surfaces

To evaluate whether the SF32-33 interacts with the P. aeruginosa cell walls, P. aeruginosa ATCC 27983 was grown in Tryptic Soy Broth (BactoTM Tryptic Soy Broth, TSB, BD, Sparks, MD, USA) for 18 h at 35°C, as previously described (Soon et al., 2011). Cells were then washed three times with sterile phosphate buffered saline (PBS, pH = 7.2) and centrifuged at 5,000 ×g for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatant was discarded, and the cells were resuspended in 10 ml of KCl solution (10 mM) and vortexed for 1 min.

The ZP was measured to determine the ability of SF32-33 to modify the electrical charge of the P. aeruginosa cell walls. ZP measurements were conducted at 25°C using a 64-channel Zetasizer Nano ZS system (Malvern) at 633 nm (red Leisure) and Malvern Laser Doppler Velocimetry patterns coupled with M3-PALS (Phase Analysis Light Scattering). Briefly, 3 ml of a P. aeruginosa cell suspension containing 1 × 108 CFU/ml was incubated with 10 μl of a SF32-33 stock solution of 23 μg/ml into a 25 ml glass container. Then, 1 ml of the mixture was transferred into a plastic cuvette (Cell-Folded Capillary DTS1060; Malvern). Titration (0–1.5 μg/ml) was performed 20 times by manual injection of 10 μl of the mixture. For each titration, the solution was transferred to the same cuvette, and the liquid charge was recorded in millivolts (mV), which was considered as the ZP. Each titration was repeated 10 times, and the results were expressed as the average of ten repetitions for each titration.

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry Assays

Isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) assays were performed to determine the thermodynamic parameters of interaction between the SF32-33 and P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853 cells in suspension. The experiments were performed in duplicate using a VP-ITC microcalorimeter at 25°C (MicroCal Company, Northampton, MA, USA). The titration consisted of 50 5-μL successive automated injections (at intervals of 300 s each) of an SF32-33 stock solution (23 μg/ml) into a cuvette containing 1.5 ml of P. aeruginosa suspension (1 × 108 CFU/ml). The SF32-33 concentrations ranged from 0 to 3.28 μg/ml. Corrections of concentrations, as well as the integration of the heat flow peaks involved in specific enthalpies of interaction (ΔinjH° in kcal/μg of SF32-33), were made using MicroCal Origin 7.0 software for ITC (Microcal, Northampton, MA, USA). Injections of SF32-33 into a cuvette charged with 1.5 ml of solvent only were used as the control in order to determine possible release of energy during titration. All solutions were prepared in 0.9% saline in Milli-Q purified water (pH = 7.0). The results were expressed as the difference of enthalpy between the solvent and SF32-33 itself (ΔinjH°).

Statistical Analysis

The data obtained in the time-kill and cytotoxicity assays were analyzed with GraphPad Prism (version 5.0; GraphPad Software, Inc. San Diego, CA, USA) using the Mann–Whitney non-parametric tests with a confidence interval of 95%. Differences between treated and control groups were considered significant for any p-value < 0.05.

Results

Characterization of the Antimicrobial Effects of the Leaf Hydroalcoholic Extract and EAF of A. glabra

Qualitative analysis of the hydroalcoholic extract of A. glabra showed a high content of flavonoids. A similar profile was found for the EAF when it was analyzed by TLC, especially for the SF32-33 fraction. Evaluation of the antimicrobial effects of A. glabra showed a MIC of 1024 μg/ml for the hydroalcoholic extract when tested against the P. aeruginosa clinical isolates and ATCC 27853 (Table 1). An MBC of 2048 μg/ml was observed for all the tested bacteria, except for one of the clinical isolates (P146c) in which the MBC was 1024 μg/ml (Table 1). EAF was highly effective against P. aeruginosa, presenting an MIC of 4–8 μg/ml and an MBC of 8–16 μg/ml (Table 1). MIC evaluation for different SFs showed that SF32-33 (4 μg/ml) was the most effective against P. aeruginosa, followed by SF18-19, which presented an MIC of 64 μg/ml (Table 2). All the other SFs tested exhibited MICs ranging from 256 to 512 μg/ml (Table 2). LC-HRMS analysis confirmed that SF32-33 is a flavonoid-rich SF containing (-) epicatechin, fisetin, quercetin, rutin, hyperosid, isoquercitrin, quercitrin, kaempferol 7-neohesperidoside, nicotiflorine, and naringenin (Table 3). Ciprofloxacin, a commercially available antimicrobial, exhibited an MIC and MBC of 32 and 64 μg/ml, respectively, for the multi-resistant clinical strain of P. aeruginosa P2C. Therefore, both SF32-33 and ciprofloxacin were able to significantly reduce P. aeruginosa growth, with reductions of 5.92 and 5.87 log CFU/ml, respectively.

Table 2.

Antimicrobial activity of different ethyl acetate fraction (EAF) sub-fractions (SF) of A. glabra on P. aeruginosa strains.

| Sub-fractions | Concentration (μg/ml) |

|

|---|---|---|

| ATCC 27853 | P2C | |

| SF 1-15 | 512 | 512 |

| SF 16-17 | 512 | 512 |

| SF 18-19 | 64 | 64 |

| SF 20-22 | 512 | 512 |

| SF 23-24 | 512 | 512 |

| SF 25-26 | 512 | 512 |

| SF 27-28 | 512 | 512 |

| SF 29-31 | 512 | 512 |

| SF 32-33 | 4 | 4 |

| SF 34-36 | 512 | 512 |

| SF 37-40 | 256 | 256 |

| SF R | 512 | 512 |

Minimum inhibitory concentrations were calculated and expressed in μg/ml. Assays were performed in duplicate on three different experiments.

Table 3.

Liquid chromatography-high resolution mass spectrometry (LC-HRMS) analysis of SF32-33.

| Compound | Rt/min | m/z [M+H]+ | Formula | Fragment ions (abundance) | Identification method | Fit score (purity) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (-) Epicatechin | 9.4 | 291.0867 | C15 H14O6 | 291.0867 (100)291.1497 (2.5) | Standard/in-house DB | 990 |

| Rutin | 14.7 | 305.0661, 611.1612 | C15 H12O7 C27H31O16 | 153.0183 (100) 185.0605 (37.8) 201.0571 (19.9) | Standard/in-house DB | 999 |

| Hyperoside | 14.9 | 465.1037 | C21 H20 O12 | 303.0502 (100)303.1152 (2.3)303.4847 (1.8) | Standard/in-house DB | 999 |

| Quercetin | 15.7 | 303.0503, 435.0929 | C15H10O7 C20H18O11 | 303.0501 (100)303.1152 (2.7)303.4851 (1.9) | Standard/in-house DB | 990 |

| Fisetin | 16.3 | 287.0554 | C15H10O6 | 287.0547 (100) 288.0580 (13.1)289.0602 (2.1) | Standard/in-house DB | 928 |

| Quercitrin | 17.0 | 303.0502,449.108 | C15H10O7C21 H20O11 | 303.0500 (100) 304.0533 (15.8)305.0558 (2.6) 449.1082 (12.8) | Standard/in-house DB | 931 |

| Kaempferol-7-neohesperidoside nicotiflorine | 19.0 | 595.1460 | C27H30O15 | 595.1460 (100) 596.1505 (63.3) 597.1533 (22.4) 625.1564 (25.3) | Standard/in-house DB | 820 |

| Naringenin | 19.9 | 773.1933, 273.0762 | C15H12O5 | 773.1933 (100)773.2955 (2.8) 774.1968 (37.6)153.0184 (100)154.0218 (6.3) | Standard/in-house DB | 990 |

Time-Kill Assays

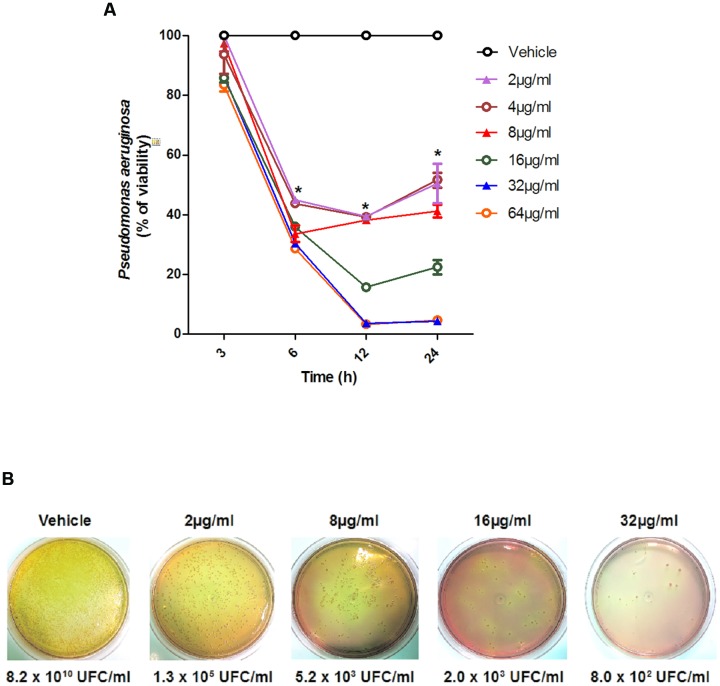

To evaluate whether the effect of SF32-33 on P. aeruginosa was time- and/or dose-dependent, we performed a time-kill assay. Figure 1 shows that SF32-33 presented a dose- and time-dependent effect on P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853 where growth inhibition was maximal at 24 h post-incubation (96% inhibition; p < 0.005).

FIGURE 1.

Time-dependent effect of SF32-33 on Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 27853 survival. (A) Percentage of P. aeruginosa viability in relation to the negative control wells (vehicle-treated) at different time points (3–24 h). (B) Representative panels of P. aeruginosa growth in CFU/ml following incubation with SF32-33 for 12 h. Assays were performed three times in duplicate. The limit of detection in the assay was of 103 CFU/ml. ∗p < 0.05; differs from the vehicle-control.

Effect of SF32-33 toward the Zeta Potential of P. aeruginosa

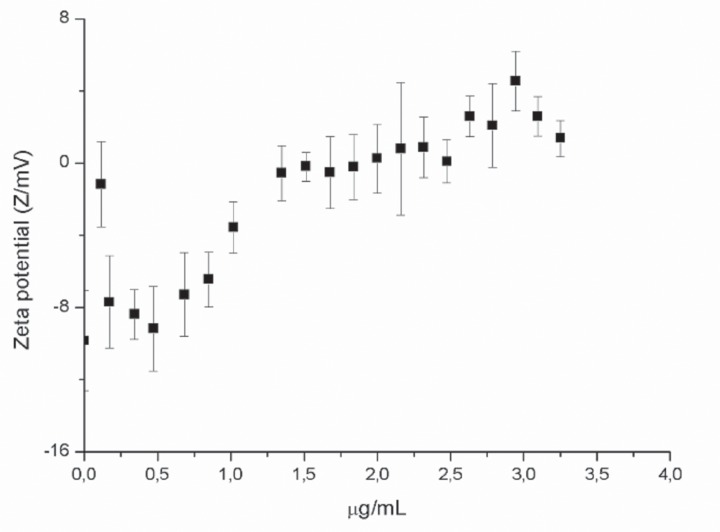

Zeta potential measurements were performed in order to investigate the ability of SF32-33 to interact with the cell wall surface of P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853. The results showed that by incubating P. aeruginosa with cumulative concentrations of SF32-33 (up to 1.5 μg/ml), there was a shift in the ZP from a negative to positive charge (-8.21 to +2.95 mV; Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Effect of flavonoids on the zeta potential (ZP) of P. aeruginosa ATCC 27983. ZP was measured in 10 mM KCl expressed in mV as a function of SF32-33 concentration. Each point represents an average of 10 repetitions for each titration.

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry Assays

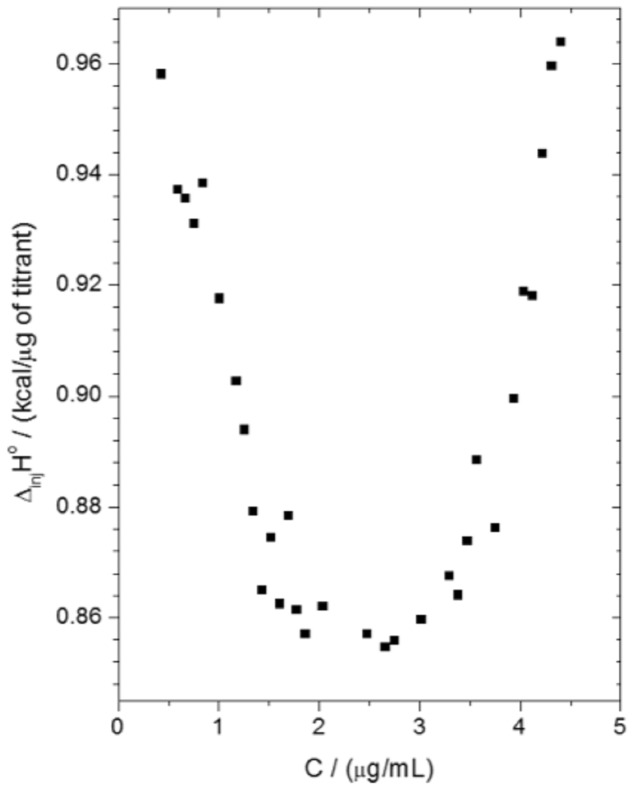

Isothermal titration calorimetry assays were performed in order to analyze the thermal profile of the interaction between SF32-33 and P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853. The data depicted in Figure 3 demonstrate that the incubation of cumulative concentrations of SF32-33 (0–3.28 μg/ml) with P. aeruginosa resulted in an endothermic reaction, as indicated by the graph of molar enthalpy of titrant – ΔinjH° (in kcal/μg of titrant), against distinct concentrations of SF32-33 in μg/ml. Furthermore, the observed parabolic profile obtained suggests that the interaction between SF32-33 and P. aeruginosa may occur through different mechanisms.

FIGURE 3.

Isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) result of the interaction thermodynamics between SF32-33 and P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853. The titration consisted of 50 5-μL successive automated injections (at intervals of 300 s each) of SF32-33 stock solution (23 μg/ml) into a cuvette containing 1.5 ml of P. aeruginosa suspension (1 × 108 CFU/ml). The results are expressed as the difference of enthalpy between the solvent and SF32-33 itself (ΔinjH° in kcal/μg).

Discussion

Although antimicrobial activities were previously reported for other Annona species, little is known on A. glabra ability to inhibit bacterial growth and/or viabilty. To the best of our knowledge we present the first evidence on that the EAF obtained from the leaf hydroalcoholic extract of A. glabra presents a potent antimicrobial activity against P. aeruginosa. We found that this activity is especially related to SF32-33, a flavonoid-rich SF of EAF. The antimicrobial actions of SF32-33 are due to its ability to interact with the bacterial cell wall surface, resulting in an endothermic reaction. These results suggest the existence of a strong binding event between SF32-33 and P. aeruginosa.

Analysis of the MIC and MBC of the hydroalcoholic extract, EAF, and SF32-33 demonstrated that the hydroalcoholic extract was not as effective as the EAF and SF32-33 in inhibiting bacterial growth and survival. By comparison, SF32-33 was the most effective against P. aeruginosa, presenting the lowest MIC and MBC. The effect of SF32-33 on P. aeruginosa viability was further investigated in a time-kill assay. SF32-33 had a dose- and time-dependent effect on P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853. Indeed, these effects were observed as soon as 6 h post-incubation of SF32-33 and lasted for 24 h. Although antibacterial activity has been attributed to fractions obtained from other plants of the Annona genus (A. vepretorum and A. hypoglauca), their MIC and MBC were much higher (≤100 mg/ml; Almeida et al., 2014; Rinaldi et al., 2016) in comparison to those observed for the EAF of A. glabra in our study (≤16 μg/ml).

The TLC and LC-HRMS results indicated that SF32-33 is rich in flavonoids. Whilst the other fractions of the extract (methanol, hexane, and dichloromethane) displayed low content of flavonoids (data not shown), partitioning of the extract with ethyl acetate allowed a greater enrichment in flavonoids. The antibacterial effects of flavonoids have been widely reported in the literature. Indeed, these effects have been attributed to their chemical structure, considering the number and positions of methoxyl and hydroxyl groups in the core C3 (Wu et al., 2013), which confer an intrinsic electrical charge and high hydrophobicity to these compounds. These characteristics favor increased membrane fluidity in the bacterial cell (Tsuchiya and Iinuma, 2000; Wu et al., 2013). In a recent study using a structure-activity relationship model, flavonoids were shown to affect Escherichia coli viability by damaging its outer membrane (Fang et al., 2016). Considering the high hydrophobicity of both flavonoids and the P. aeruginosa cell wall, it is possible that SF32-33 has an effect on P. aeruginosa viability and growth due to a strong hydrophobic interaction.

By performing an LC-HRMS analysis, it was possible to identify different flavonoids in the SF32-33, including (-)-epicatechin, fisetin, quercetin, rutin (quercetin glycoside), hyperosid, isoquercitrin, quercitrin, kaempferol 7-neohesperidoside, nicotiflorine, and naringenin. To our knowledge, we present the first evidence of the compounds found in the EAF of A. glabra. Many of them have already been shown to present antimicrobial actions against different bacteria, but little is known of their ability to inhibit P. aeruginosa growth/viability.

The structure of (-) epicatechin is composed of two aromatic rings linked by an oxygen heterocycle with a 4-hydroxyl group (Fraga and Oteiza, 2011). Epicatechins are flavan-3-ols, a subfamily of flavonoid polyphenolic compounds that are abundant in grape seeds and peels, green tea, nuts, and berries. Epicatechins, such as (-)-epicatechin gallate, inhibit the expression of virulence genes associated with secretion of proteins in Staphylococcus aureus (Shah et al., 2008). To the best of our knowledge, few reports have characterized epicatechins isolated from the leaves of plants of the Annonaceae family, and even fewer reports have been published on their antibacterial actions (Lage et al., 2014). Fisetin (3,3′,4′,7-tetrahydroxyflavone), another biologically active flavonoid, was also identified in SF32-33. Although this compound does not present antimicrobial properties, it has been suggested as a possible anti-virulence approach. Indeed, fisetin inhibits the action of listeriolysin O, a hemolytic toxin produced by Listeria monocytogenes whose main function is to facilitate bacterial replication and evasion from the host immune system (Wang et al., 2015). Another compound identified in SF32-33 is quercetin (3,3′,4′,5,7-pentahydroxyflavone). Reports have shown a potential use for this compound when combined with either epigallocatechin-3-gallate c, against drug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Dey et al., 2015), or oxacillin, causing damage in the cell walls of multi-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (Amin et al., 2015). It is possible that all the compounds identified herein act synergistically, contributing to the antimicrobial effects of SF32-33.

We next assessed the ability of SF32-33 to interact with the cell wall of P. aeruginosa. We found that incubation of SF32-33 with P. aeruginosa caused a shift in the ZP from a negative to positive charge. We suggest that this interaction is mediated by the flavonoids present in the SF32-33. In fact, flavonoids have been reported to interact with E. coli cell wall proteins, changing their structure, and this has been associated with an increase in ZP (Wu et al., 2013). We additionally performed ITC assays and found that the incubation of SF32-33 with P. aeruginosa promotes an endothermic reaction. We suggest that this entropic reaction is a result of the hydrophobic interactions between flavonoids in the SF32-33 and the bacterial cell wall surface, leading to a high extension of desolvation of ions and water molecules. These data taken together suggest that the interactions between SF32-33 and the P. aeruginosa cell wall account for the antibacterial actions of this A. glabra SF.

Collectively, our results show that flavonoids obtained from the EAF of A. glabra are effective against P. aeruginosa due to their ability to interact with the bacterial cell wall, and thus, may represent an alternative treatment for P. aeruginosa infection.

AuthOr Contributions

SG collected the plants, prepared the extracts, performed the experiments, and wrote the manuscript; AM and MB collaborated on antimicrobial assays and data interpretation; GF, ES, ÁS, AD, MD-S, VS, and ES-F performed the chemical characterization, ZP contributed to ITC determination assays and data interpretation; EF contributed to statistical analysis, data interpretation, and critically revised the manuscript; VM-N contributed to the conception of the study, study design and coordination and critically revised the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final version for publication.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nivel Superior (CAPES, Brazil, No. 3325/2013), Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa e Desenvolvimento Científico do Maranhão (FAPEMA, Brazil, No. 3628/13), and Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq, Brazil, No. 482037). SG is an M.Sc. student receiving a grant from FAPEMA. MD-S is a post-doctoral student funded by the Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de Minas Gerais (FAPEMIG).

References

- Almeida J. R. G. S., Araújo C. S., Pessoa C. O., Costa M. P., Pacheco A. G. M. (2014). Antioxidant, cytotoxic and antimicrobial activity of Annona vepretorum Mart. (Annonaceae). Rev. Bras. Frutic. 36 258–264. 10.1590/S0100-29452014000500030 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Amin M. U., Khurram M., Khattak B., Khan J. (2015). Antibiotic additive and synergistic action of rutin, morin and quercetin against methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 15:59 10.1186/s12906-015-0580-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao X. Q., Wu L. Y., Wang X. L., Sun H., Zhang D. (2015). Squamosamide derivative FLZ protected tyrosine hydroxylase function in a chronic MPTP/probenecid mouse model of Parkinson’s disease. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 388 549–556. 10.1007/s00210-015-1094-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C. H., Hsieh T. J., Liu T. Z., Chern C. L., Hsieh P. Y., Chen C. Y. (2004). Annoglabayin, a novel dimeric kaurane diterpenoid, and apoptosis in Hep G2 cells of annomontacin from the fruits of Annona glabra. J. Nat. Prod. 67 1942–1946. 10.1021/np040078j [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CLSI (2015). Methods for Dilution Antimicrobial Susceptibility Tests for Bacteria that Grow Aerobically; Approved Standard. CLSI Document M07-A10. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Cochrane C. B., Nair P. K., Melnick S. J., Resek A. P., Ramachandran C. (2008). Anticancer effects of Annona glabra plant extracts in human leukemia cell lines. Anticancer Res. 28 965–971. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Siqueira E. P., de Souza-Fagundes E. M., Ramos J. P., Kohlhoff M., Nunes Y. R. F., Campos F. F., et al. (2014). In vitro antibacterial action on methicillin-susceptible (MSSA) and methicillin-resistant (MRSA) Staphylococcus aureus and antitumor potential of Mauritia flexuosa L. f. J. Med. Plants Res. 8 1408–1417. [Google Scholar]

- Dey D., Ray R., Hazra B. (2015). Antimicrobial activity of pomegranate fruit constituents against drug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis and beta-lactamase producing Klebsiella pneumoniae. Pharm. Biol. 53 1474–1480. 10.3109/13880209.2014.986687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang Y., Lu Y., Zang X., Wu T., Qi X., Pan S., et al. (2016). 3D-QSAR and docking studies of flavonoids as potent Escherichia coli inhibitors. Sci. Rep. 6:23634 10.1038/srep23634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraga C. G., Oteiza P. I. (2011). Dietary flavonoids: role of (-)-epicatechin and related procyanidins in cell signaling. Free Radic Biol. Med. 51 813–823. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi K., Fukushima A., Hayashi-Nishino M., Nishino K. (2014). Effect of methylglyoxal on multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Front. Microbiol. 5:180 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horai H., Arita M., Kanaya S., Nihei Y., Ikeda T., Suwa K., et al. (2010). MassBank: a public repository for sharing mass spectral data for life sciences. J. Mass Spectrom. 45 703–714. 10.1002/jms.1777 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lage G. A., Medeiros Fda S., Furtado Wde L., Takahashi J. A., de Souza Filho J. D., Pimenta L. P. (2014). The first report on flavonoid isolation from Annona crassiflora Mart. Nat. Prod. Res. 28 808–811. 10.1080/14786419.2014.885518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morita Y., Nakashima K., Nishino K., Kotani K., Tomida J., Inoue M., et al. (2016). Berberine is a novel type efflux inhibitor which attenuates the MexXY-mediated aminoglycoside resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Front. Microbiol. 7:1223 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morita Y., Tomida J., Kawamura Y. (2014). Responses of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to antimicrobials. Front. Microbiol. 4:422 10.3389/fmicb.2013.00422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Núñez-Elisea R., Schaffer B., Fisher J. B., Colls A. M., Crane J. H. (1999). Influence of flooding on net CO2 assimilation, growth and stem anatomy of Annona species. Ann. Bot. 84 771–780. 10.1006/anbo.1999.0977 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ozer B., Tatman-Otkun M., Memis D., Otkun M. (2009). Characteristics of Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from intensive care unit. Open Med. 4 156–163. 10.2478/s11536-008-0090-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Padmaja V., Thankamany V., Hara N., Fujimoto Y., Hisham A. (1995). Biological activities of Annona glabra. J. Ethnopharmacol. 48 21–24. 10.1016/0378-8741(95)01277-K [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pankey G. A., Sabath L. D. (2004). Clinical relevance of bacteriostatic versus bactericidal mechanisms of action in the treatment of Gram-positive bacterial infections. Clin. Infect. Dis. 38 864–870. 10.1086/381972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poole K. (2011). Pseudomonas aeruginosa: resistance to the max. Front. Microbiol. 2:65 10.3389/fmicb.2011.00065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porras-Gomez M., Vega-Baudrit J., Nunez-Corrales S. (2012). Overview of multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa and novel therapeutic approaches. J. Biomat. Nanobiotechnol. 3 519–527. 10.4236/jbnb.2012.324053 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rinaldi M. V. N., Díaz I. E. C., Suffredini I. B., Moreno P. R. H. (2016). Alkaloids and biological activity of beribá (Annona hypoglauca). Rev. Bras. Farmacogn. 10.1016/j.bjp.2016.08.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shah S., Stapleton P. D., Taylor P. W. (2008). The polyphenol (-)-epicatechin gallate disrupts the secretion of virulence-related proteins by Staphylococcus aureus. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 46 181–185. 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2007.02296.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soon R. L., Nation R. L., Cockram S., Moffatt J. H., Harper M., Adler B., et al. (2011). Different surface charge of colistin-susceptible and -resistant Acinetobacter baumannii cells measured with zeta potential as a function of growth phase and colistin treatment. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 66 126–133. 10.1093/jac/dkq422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuchiya H., Iinuma M. (2000). Reduction of membrane fluidity by antibacterial sophoraflavanone G isolated from Sophora exigua. Phytomedicine 7 161–165. 10.1016/S0944-7113(00)80089-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Undabarrena A., Beltrametti F., Claverias F. P., Gonzalez M., Moore E. R., Seeger M., et al. (2016). Exploring the diversity and antimicrobial potential of marine actinobacteria from the comau fjord in northern patagonia. Chile. Front. Microbiol. 7:1135 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Qiu J., Tan W., Zhang Y., Wang H., Zhou X., et al. (2015). Fisetin inhibits Listeria monocytogenes virulence by interfering with the oligomerization of listeriolysin O. J. Infect. Dis. 211 1376–1387. 10.1093/infdis/jiu520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wroblewska M. (2006). Novel therapies of multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Acinetobacter spp. infections: the state of the art. Arch. Immunol. Ther. Exp. (Warsz) 54 113–120. 10.1007/s00005-006-0012-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu T., He M., Zang X., Zhou Y., Qiu T., Pan S., et al. (2013). A structure-activity relationship study of flavonoids as inhibitors of E. coli by membrane interaction effect. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1828 2751–2756. 10.1016/j.bbamem.2013.07.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H., Wang M., Yu J., Wei H. (2015). Antibacterial activity of a novel peptide-modified lysin against Acinetobacter baumannii and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Front. Microbiol. 6:1471 10.3389/fmicb.2015.01471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y. H., Peng H. Y., Xia G. H., Wang M. Y., Han Y. (2004). Anticancer effect of two diterpenoid compounds isolated from Annona glabra Linn. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 25 937–942. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]