Abstract

About 30% of the world's ice-free land area is occupied by acid soils. In soils with pH below 5, aluminum (Al) releases to the soil solution, and becomes highly toxic for plants. Therefore, breeding of varieties that are resistant to Al is needed. Flax (Linum usitatissimum L.) is grown worldwide for fiber and seed production. Al toxicity in acid soils is a serious problem for flax cultivation. However, very little is known about mechanisms of flax resistance to Al and the genetics of this resistance. In the present work, we sequenced 16 transcriptomes of flax cultivars resistant (Hermes and TMP1919) and sensitive (Lira and Orshanskiy) to Al, which were exposed to control conditions and aluminum treatment for 4, 12, and 24 h. In total, 44.9–63.3 million paired-end 100-nucleotide reads were generated for each sequencing library. Based on the obtained high-throughput sequencing data, genes with differential expression under aluminum exposure were revealed in flax. The majority of the top 50 up-regulated genes were involved in transmembrane transport and transporter activity in both the Al-resistant and Al-sensitive cultivars. However, genes encoding proteins with glutathione transferase and UDP-glycosyltransferase activity were in the top 50 up-regulated genes only in the flax cultivars resistant to aluminum. For qPCR analysis in extended sampling, two UDP-glycosyltransferases (UGTs), and three glutathione S-transferases (GSTs) were selected. The general trend of alterations in the expression of the examined genes was the up-regulation under Al stress, especially after 4 h of Al exposure. Moreover, in the flax cultivars resistant to aluminum, the increase in expression was more pronounced than that in the sensitive cultivars. We speculate that the defense against the Al toxicity via GST antioxidant activity is the probable mechanism of the response of flax plants to aluminum stress. We also suggest that UGTs could be involved in cell wall modification and protection from reactive oxygen species (ROS) in response to Al stress in L. usitatissimum. Thus, GSTs and UGTs, probably, play an important role in the response of flax to Al via detoxification of ROS and cell wall modification.

Keywords: Linum usitatissimum, flax, aluminum stress, acid soil, transcriptome sequencing, gene expression, glutathione S-transferase, UDP-glycosyltransferase

Introduction

About 30% of the world's ice-free land area is occupied by acid soils (Von Uexküll and Mutert, 1995). Soil acidification results from acidic precipitation, deposition of acidifying gasses, or particles from the atmosphere, application of acidifying fertilizers, and mineralization of organic matter (Goulding, 2016). Moreover, anthropogenic pressure can result in further soil acidification (Guo et al., 2010; Lawrence et al., 2013). In soils with pH below 5, aluminum (Al) is solubilized to Al3+ ionic forms, which are released into the soil solution, and become highly toxic for plants by inhibiting the root function and growth (Kinraide, 1991; Zheng, 2010). Lands, which are preferable for plant cultivation, are already in agricultural use. Intensive soil exploitation can result in soil erosion and further decrease in cultivable areas. As human population is increasing rapidly, crop production also needs to keep pace with it (Godfray et al., 2010). Therefore, plant cultivation on unfavorable soils is necessary and breeding of varieties, which are resistant to Al and other stress factors, is needed.

The search for mechanisms involved in the response of plants to Al has revealed different strategies for adaptation, including Al avoidance and Al tolerance. One of the best-characterized mechanisms is organic acid exudation to chelate Al3+ and prevent its entry into the root (Yang et al., 2013). Aluminum tolerance mechanisms include detoxification of its harmful compounds, modification of cell wall properties, transport of Al to shoots, and its storage in innocuous forms, etc. (Grevenstuk and Romano, 2013; Kochian et al., 2015; Sade et al., 2016).

Diverse plant species have different strategies for Al resistance; these have been described for various plants, including wheat (Delhaize et al., 1993; Garcia-Oliveira et al., 2013; Moustaka et al., 2016), barley (Furukawa et al., 2007; Ma et al., 2016), sorghum (Magalhaes et al., 2007; Caniato et al., 2014), rice (Ma et al., 2002; Yokosho et al., 2011; Xia et al., 2013; Arenhart et al., 2014), maize (Piñeros et al., 2002; Maron et al., 2013), Arabidopsis (Liu et al., 2009; Mangeon et al., 2016), snap bean (Miyasaka et al., 1991), buckwheat (Zhu et al., 2015), eucalyptus (Tahara et al., 2014), and hydrangea (Negishi et al., 2013).

Flax (Linum usitatissimum L.) is grown worldwide for fiber and seeds and has attracted the attention of scientists (Muir and Westcott, 2003; Johnson et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2012; Melnikova et al., 2014a,b). L. usitatissimum has 2n = 30 chromosomes, whereas the chromosome number in different species of the genus Linum varies from 2n = 16 to 2n = 84 (Rogers, 1982; Bolsheva et al., 2015). Nuclear DNA content of flax has been evaluated to be 352 Mb by reassociation kinetics analysis and 373 Mb by flow cytometry (Cullis, 1981; Wang et al., 2012). The L. usitatissimum genome has been sequenced using whole-genome shotgun sequencing, and has been predicted to contain 43,384 protein-coding genes (Wang et al., 2012). High-throughput sequencing approaches have also been applied to determine the genetic polymorphism within flax genotypes (Fu and Peterson, 2012; Kumar et al., 2012; Galindo-Gonzalez et al., 2015; Fu et al., 2016). Expression analysis allows scientists to identify genes that are expressed in particular flax tissues (Day et al., 2005; Venglat et al., 2011; Zhang and Deyholos, 2016). Moreover, the responses of flax to drought (Dash et al., 2014), salinity, and alkalinity stresses (Yu et al., 2016), nutrient imbalance (Dmitriev et al., 2016), and Fusarium oxysporum infection (Wojtasik et al., 2015, 2016) have been studied and stress-responsive genes identified.

Al toxicity in acid soils is a serious problem for cultivation and rich harvest of flax (Kishlyan and Rozhmina, 2010). However, very little is known about the mechanisms of resistance of flax to Al and the genetics of resistance. It has been shown that high concentration of boron affects the phenolic metabolism of flax and decreases the Al toxicity (Heidarabadi et al., 2011). In the present work, we sequenced the transcriptomes of Al-resistant and -sensitive flax cultivars grown under control or Al-treated conditions to identify genes involved in Al resistance. We also evaluated the expression of genes that potentially participate in the Al response in extended sampling using qPCR and suggested probable mechanisms for aluminum resistance in L. usitatissimum.

Materials and methods

Plant material

Flax (L. usitatissimum) plants of two cultivars resistant (Hermes and TMP1919) and two sensitive (Lira and Orshanskiy) to aluminum stress were used in this study. The seeds were germinated on filter paper soaked with distilled water at 21°C for 5 days. The seedlings were then transferred to Falcon tubes containing filter paper soaked in 0.5 mM CaCl2 solution at pH 4.5 and adapted for 24 h. Thereafter, to assess the effect of Al, the seedlings were grown for 1 day under different conditions: (1) in the presence of 0.5 mM CaCl2 solution at pH 4.5 for 24 h (N); (2) in the presence of 0.5 mM CaCl2 solution at pH 4.5 for 20 h and then in the presence of 0.5 mM CaCl2 solution containing 500 μM AlCl3 at pH 4.5 for 4 h (Al-4); (3) in the presence of 0.5 mM CaCl2 solution at pH 4.5 for 12 h and then in the presence of 0.5 mM CaCl2 solution containing 500 μM AlCl3 at pH 4.5 for 12 h (Al-12); (4) in the presence of 0.5 mM CaCl2 solution containing 500 μM AlCl3 at pH 4.5 for 24 h (Al-24). Root tips, 8–10 mm in length, were sampled and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen. Plant samples were stored at −70°C. Total RNA was extracted from individual plants using an RNA MiniPrep kit (Zymo Research, USA). In total, 80 RNA samples were obtained: 5 from each of the four cultivars grown under N, Al-4, Al-12, and Al-24 conditions. The RNA quality and concentration were evaluated using Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, USA) and Qubit 2.0 fluorometer (Life Technologies, USA). For further analysis, only high-quality RNA samples with RNA Integrity Number (RIN) not <8.0 were used.

Transcriptome sequencing

The RNA samples from each cultivar grown under the same conditions were pooled in equimolar concentrations and 16 pooled RNA samples from the four cultivars under N, Al-4, Al-12, and Al-24 conditions were used for cDNA library preparation with TruSeq RNA SamplePrep (Illumina, USA). The quality of 16 libraries thus obtained was evaluated using Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies). Eventually, the libraries were sequenced on HiSeq2500 (Illumina) platform.

Transcriptome assembly and differential expression analysis

Illumina reads for each cultivar were trimmed and filtered using Trimmomatic (Bolger et al., 2014) and then transferred for transcriptome assembly to Trinity, which was used with default parameters (Grabherr et al., 2011). The quality of all the four assemblies (Lira, Orshanskiy, Hermes, and TMP1919) was assessed with N50. Contigs <200 nucleotides were excluded from the further analysis. The derived transcript sequences were analyzed for the presence of ORF using TransDecoder (Haas et al., 2013). The transcripts and their predicted proteins were annotated using Trinotate (http://trinotate.github.io/). The transcripts and proteins were aligned to the UniProt database using blastx and blastp, respectively. For each transcript/protein, only the best blast hit was chosen for further analysis. The protein sequences were scanned for the presence of PFAM domains using HMMER (Punta et al., 2012; Finn et al., 2015). Based on these data, a local SQLite database was constructed and transferred to Trinotate. The mapped transcripts and proteins were annotated with Gene Ontology, KEGG, and COG entries.

The reads were mapped to the assembled transcripts and quantified using bowtie2 (Langmead and Salzberg, 2012) and rsem (Li and Dewey, 2011) at both the transcript and gene levels by two methods: (1) for each cultivar, the reads were mapped to the corresponding transcriptome; (2) the reads from all the cultivars were mapped to the Hermes transcriptome. Each method has its own disadvantages, namely: (1) the sets of assembled transcripts may significantly differ between the cultivars; (2) the cultivars may be genetically divergent, and reads can fail to align. The second method led to better results and allowed us to obtain more consensual expression data in groups of sensitive and resistant cultivars. We used bowtie2, because it is more tolerant to mismatches and indels than bowtie.

The derived read count data were analyzed using edgeR (Robinson et al., 2010). Transcripts with CPM (count per million) below 1.5 were filtered out. After normalization with TMM method, we applied approximation of the observed expression levels with two generalized linear models (GLM; values are presented for N, Al-4, Al-12, and Al-24 conditions): [0,1,2,3] and [0,1,1,1]. Approximation with the first model allows the identification of genes whose expression levels gradually change with the exposure time. The second model describes genes that are differentially expressed under any time of Al exposure. GLM [0,1,1,1] allowed us to find alterations that were specific to resistant cultivars. The results obtained with this model were used for choosing differentially expressed transcripts for further qPCR analysis. To assess the alterations of expression for each transcript in case of GLM [0,1,1,1], fold change values were calculated in the pool of resistant and pool of sensitive cultivars as follows:

The gene set enrichment analysis with gene ontology data was performed using Goseq (http://bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/goseq.html). The analysis of the altered KEGG pathways was done with Pathview, a Bioconductor package (Luo and Brouwer, 2013).

qPCR analysis

For qPCR analysis, 80 RNA samples of Hermes, TMP1919, Lira, and Orshanskiy grown under N, Al-4, Al-12, and Al-24 conditions were used. The differentially expressed transcripts were identified using the transcriptome sequencing data. The primers for five of such transcripts (Table 1) were designed using ProbeFinder Software (Roche, Switzerland). PCR was performed using a 7500 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, USA) in 20-μl reaction mix containing 1X PCR mix (GenLab, Russia), 250 nM of dNTPs mix (Fermentas, Lithuania), 300 nM of forward and reverse primers, 2 U of TaqF polymerase (GenLab), 200 nM of short hydrolysis probes from Universal ProbeLibrary (Roche), and cDNA. The following amplification program was used: 95°C for 10 min, 50 cycles of 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 60 s. Three technical replicates were performed. ETIF3H and ETIF3E were chosen as the reference genes for the qPCR data analysis (Huis et al., 2010; Melnikova et al., 2016). All the calculations were performed using the Analysis of Transcription of Genes software (Krasnov et al., 2011). For the evaluation of expression levels, and values were calculated (Melnikova et al., 2015, 2016).

Table 1.

Primers and probes used in the study.

| Primer name | Primer sequence | Probe number from Roche Universal ProbeLibrary |

|---|---|---|

| GST23.2-F | AAACCCATTTCCGAATCCAT | 65 |

| GST23.2-R | TGGCATCAGTGGGTAGGTTT | |

| GST23-F | GAGCATGATGACACACATTGAA | 16 |

| GST23-R | CGCAGGGGAATGATACTCTC | |

| GSTU8-F | GGTGACTAGCTCAATCCCAATG | 31 |

| GSTU8-R | CTGCAAACTTCGTCGGGTAT | |

| UGT71-F | GAGGTGAGAAAGAAGGTAAAGGAAA | 52 |

| UGT71-R | TGACGATCCACCTTCATTCA | |

| UGT74-F | CCTTCCATAACTCCCCTCAAA | 22 |

| UGT74-R | GAAGAATGAAGAAGGGATTGTGA | |

| ETIF3E-F | TTACTGTCGCATCCATCAGC* | 53 |

| ETIF3E-R | GGAGTTGCGGATGAGGTTTA* | |

| ETIF3H-F | CAGCGTGCTTGAAGTAACCA* | 38 |

| ETIF3H-R | AACCTCCCTCAAGCATCTCA* |

– Primer sequences are from Huis et al. (2010).

where Ct is the replicate-averaged threshold cycle, and E is the efficiency of reaction for each pair of the primers.

Mann—Whitney and Kruskal—Wallis rank-sum tests were used for the assessment of statistical significance of the revealed expression alterations. Correlation between high-throughput sequencing (CPM) and qPCR (median()) expression data was evaluated using Spearman's correlation coefficient.

Results

High-throughput sequencing of flax transcriptomes under Al treatment

Sixteen cDNA flax libraries (obtained from the four cultivars under N, Al-4, Al-12, and Al-24 conditions) were sequenced using HiSeq2500. In total, 44.9–63.3 million paired-end 100-nucleotide reads were generated for each library (Sequence Read Archive – SRP089959). The transcriptomes for each cultivar were assembled separately. The assembly statistics are shown in Table 2; all four cultivars demonstrated very similar statistics. About 122–126 thousand transcripts, related to 72–75 thousand “genes,” were derived for each cultivar. The annotation of transcripts was performed for Hermes, Lira, Orshanskiy, and TMP1919 cultivars. About 60% of the transcripts were successfully mapped to UniProt using blastx. For almost 70% of the 125 thousand transcripts, we found long ORFs, 47% of which were mapped to UniProt using blastp. For 46% ORFs, PFAM domains were detected. About 18 thousand transcripts passed the CPM threshold and were used for differential expression analysis.

Table 2.

Transcriptome assembly statistics for the examined flax cultivars.

| Hermes | TMP1919 | Lira | Orshanskiy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genes | 74,985 | 72,285 | 75,121 | 75,028 |

| Transcripts | 123,953 | 124,071 | 122,572 | 126,408 |

| GC-content | 45 | 44 | 45 | 44 |

| N50 | 1861 | 1838 | 1871 | 1857 |

| Median contig length | 765 | 767 | 757 | 761 |

| Average contig length | 1148 | 1142 | 1150 | 1150 |

| Total assembled bases, Mb | 143.5 | 141.7 | 141.0 | 145.2 |

| Transcripts with found ORF | 85,706 | 84,438 | 86,698 | 85,078 |

| Transcripts mapped to UniProt (BLASTx) | 75,222 | 73,921 | 75,526 | 74,936 |

| Transcripts with ORF mapped to UniProt (BLASTp) | 41,321 | 40,712 | 41,408 | 40,631 |

| Transcripts with ORF mapped to PFAM (HMMER) | 39,677 | 39,027 | 39,327 | 39,422 |

| Transcripts annotated with KEGG | 38,989 | 38,558 | 38,843 | 38,931 |

| Transcripts annotated with Gene Ontology (BLAST) | 45,366 | 45,572 | 45,597 | 45,339 |

| Transcripts annotated with Gene Ontology (PFAM) | 24,488 | 25,256 | 24,924 | 24,901 |

Identification of aluminum responsive genes on the basis of flax transcriptome sequencing

For identification of aluminum responsive genes in flax, the expression level of each transcript was estimated for each of the four studied cultivars under N, Al-4, Al-12, and Al-24 conditions, pools of resistant and sensitive cultivars under N, Al-4, Al-12, and Al-24 conditions, and pools of resistant and sensitive cultivars under N and under Al treatment (combined Al-4, Al-12, and Al-24). For further analysis, differential gene expression under Al treatment was evaluated for the pool of resistant (S1 Table) and pool of sensitive (S2 Table) cultivars using GLM [0,1,1,1]. Gene ontology analysis was performed for top 50 up- and down-regulated genes in the resistant and sensitive cultivars. The up-regulated genes were involved in transmembrane transport and transporter activity both in the resistant (S3 Table) and sensitive (S4 Table) cultivars. However, the genes encoding proteins with glutathione transferase and UDP-glycosyltransferase activity were in the top 50 up-regulated genes only in the cultivars resistant to aluminum: the up-regulation of UDP-glycosyltransferases (log2FC varied from 1.0 to 2.4) and glutathione S-transferases (log2FC = 1.1–1.2) was observed under Al stress. UDP-glycosyltransferases are involved in various biological processes, including plant stress response (Li et al., 2015). Glutathione S-transferases are anti-oxidant enzymes, which participate in Al response (Richards et al., 1998; Ezaki et al., 2000). A majority of the top 50 down-regulated genes was involved in photosynthesis and “extracellular region” in cultivars resistant to Al (S5 Table) and in the transport of different compounds in the sensitive cultivars (S6 Table). Peroxidase genes were also in the top 50 genes down-regulated under Al treatment in flax.

We also analyzed the expression of genes encoding aluminum-activated malate transporters (ALMTs), ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters, sensitive to proton rhizotoxicity 1 (STOP1), and aquaporins, which are known to be involved in Al responses in other plant species (Kochian et al., 2015). ALMTs were identified to be involved in Al resistance in bread wheat (Sasaki et al., 2004), sorghum (Magalhaes et al., 2007), Arabidopsis (Hoekenga et al., 2006; Liu et al., 2009), etc. We detected ALMT transcripts in flax and observed a decrease or retention in ALMT gene expression in Al-sensitive cultivars (log2FC varied from −0.78 to 0.06) and no significant alteration in the expression in the Al-resistant cultivars (log2FC varied from −0.28 to 0.05). Thus, we did not observe any increase in expression in flax under Al exposure for aluminum-activated malate transporters, which are involved in one of the most studied mechanisms of plant Al avoidance, i.e., root exudation of organic acid to chelate Al3+. ABC transporters participate in resistance to Al in Arabidopsis (Larsen et al., 2005) and rice (Huang et al., 2012). We observed alterations in the expression of the ABC transporter family members in all the studied cultivars, but these changes were not unidirectional: log2FC varied from −1.01 to 0.96 in the resistant cultivars and from −0.75 to 1.19 in the sensitive cultivars. The ABC transporter B family member 15 was in the top 50 down-regulated genes in the sensitive flax cultivars. We also identified homologs of STOP1 (transcription factor, which is involved in aluminum resistance; Fan et al., 2016) in the flax transcriptome sequencing data, but did not observe alterations in the expression under Al stress. HmPALT and HmVALT are identified in hydrangea as Al-transporting aquaporins (Negishi et al., 2012, 2013). In flax, we observed down-regulation for the most of aquaporin family members.

It is known that exposure of plants to aluminum under acid conditions results in the induction of the aluminum resistance genes and their expression is higher in the resistant genotypes than in the sensitive ones (Liu et al., 2014; Kochian et al., 2015). Therefore, the genes that were up-regulated under Al stress in the resistant flax cultivars were the most prospectively useful for further analysis.

qPCR analysis of gene expression in flax under aluminum stress

For qPCR analysis in extended sampling, five genes with increase in their expression under Al stress were selected. These genes encode the following proteins: probable glutathione transferase GST23 (GST23.2), glutathione transferase GST23, glutathione S-transferase U8 (GSTU8), UDP-glycosyltransferase 71K2 (UGT71), and UDP-glycosyltransferase 74F1 (UGT74) (S7 Table). Five primer pairs were designed, and the expression levels of the selected transcripts (GST23.2, GST23, GSTU8, UGT71, and UGT74) were assessed in 80 RNA samples from individual flax plants of the two resistant (Hermes and TMP1919) and two sensitive (Lira and Orshanskiy) to Al cultivars, which were grown under N, Al-4, Al-12, and Al-24 conditions (five samples for each group).

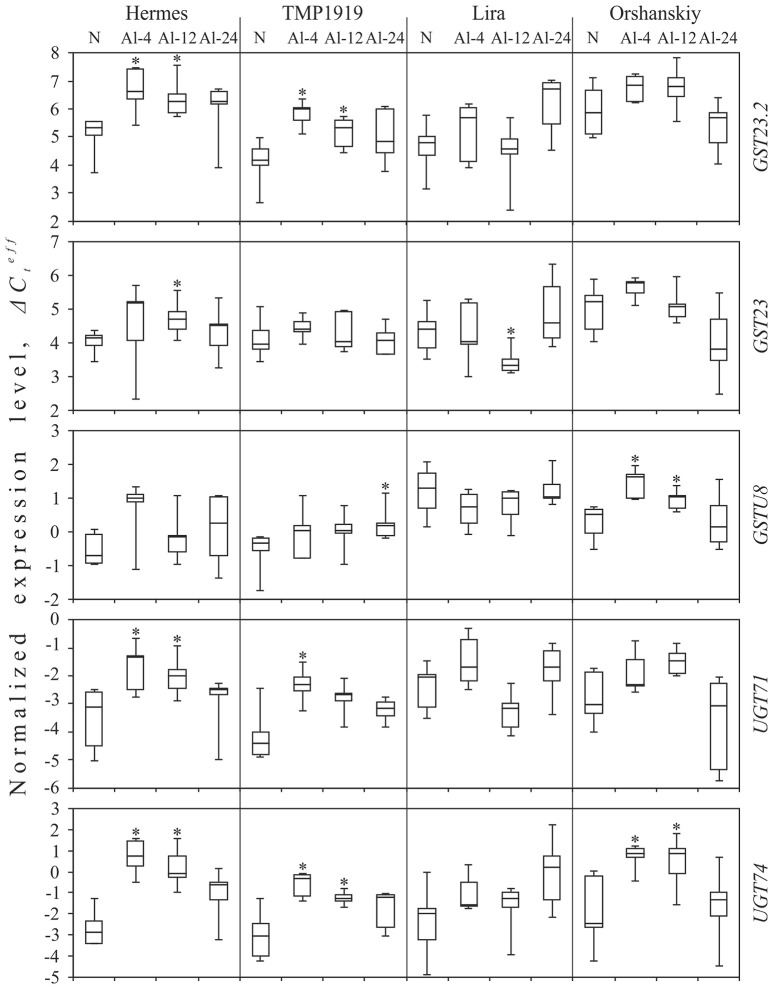

For the GST23.2 transcript (TR43855|c1_g1), a statistically significant increase in expression (p < 0.05) was observed for the resistant cultivars, Hermes, and TMP1919, under Al-4 and Al-12 conditions: for Hermes was 1.3 under Al-4, and 1.0 under Al-12 conditions; for TMP1919 was 1.8 under Al-4 and 1.1 under Al-12 conditions (Figure 1). For the sensitive cultivars, Lira and Orshanskiy, the tendency of alterations in the expression of GST23.2 was similar to that in the resistant ones, but the changes were not statistically significant.

Figure 1.

Expression level () of five genes under Al exposure in the resistant (Hermes and TMP1919) and sensitive (Lira and Orshanskiy) flax cultivars. qPCR data. N, normal conditions (control); Al-4/-12/-24, aluminum exposure during 4/12/24 h. Rectangles correspond to the ranges containing 50% of the values (between the 25th and 75th percentile); the horizontal line inside the rectangle is the median value (the 50th percentiles); the bars are the maximum and minimum values. Statistically significant (p < 0.05) expression changes under treatment conditions (Al-4, Al-12, or Al-24) compared to control conditions (N) are marked with asterisks.

For GST23 transcript (TR53691|c0_g1), we observed an increase in the expression under Al-4 condition for Hermes, TMP1919, and Orshanskiy cultivars, but the changes were not statistically significant. However, under the Al-12 condition, the alterations were statistically significant, but had opposite directions for Hermes ( = 0.6) and Lira ( = −1.1).

For the GSTU8 transcript (TR41172|c0_g1), an increase in expression was observed under Al-4 condition for Hermes, TMP1919, and Orshanskiy cultivars, but it was statistically significant only for Orshanskiy ( = 1.1). Significant up-regulation was also revealed for Orshanskiy under Al-12 ( = 0.5) and for TMP1919 under Al-24 condition ( = 0.5).

UGT71 (TR25219|c0_g1) expression was significantly increased under Al-4 conditions for both the resistant cultivars ( was 1.8 for Hermes and 2.1 for TMP1919) and under Al-12 condition only for Hermes ( = 1.2). At the same time, the increasing trend in UGT71 expression under Al-4 was revealed for all the studied cultivars.

For the UGT74 transcript (TR50184|c0_g1), we observed an up-regulation in the expression under all the three Al treatments for all the studied cultivars. The increase was statistically significant for Hermes, TMP1919, and Orshanskiy cultivars under Al-4 and Al-12 conditions: was 3.6 under Al-4 and 2.8 under Al-12 for Hermes, 2.8 under Al-4 and 1.8 under Al-12 for TMP1919, and 3.3 under Al-4 and Al-12 for Orshanskiy.

Thus, the general trend of alterations in the expression in flax was the up-regulation of UGT and GST coding genes under Al stress, especially after 4 h of Al exposure. Besides, in the flax cultivars resistant to aluminum, the increase in expression was more pronounced than in the sensitive ones.

Discussion

Aluminum toxicity in acid soils results in the decrease in the yield of flax plants. Therefore, the search for sources of L. usitatissimum resistance to Al is essential (Kishlyan and Rozhmina, 2010). However, for breeding of cultivars resistant to aluminum, not only the identification of resistant genotypes, but also an understanding of the genetics of resistance is required. The induction in the expression of aluminum resistance genes under Al exposure was revealed in different plant species (Liu et al., 2014). Besides, the expression of resistance genes under Al treatment was found to be higher in the resistant genotypes than in the sensitive ones (Kochian et al., 2015). Therefore, the genes with increased expression under Al treatment, especially in the resistant cultivars, are the most promising candidates for the resistance genes. For identification of the mechanisms for Al response in flax, we assessed gene expression in the cultivars resistant and sensitive to Al under control and Al treatment conditions using high-throughput sequencing and qPCR analysis. We observed the up-regulation of UDP-glycosyltransferase and glutathione S-transferase genes in flax plants under Al stress based on both high-throughput sequencing and qPCR data. The data obtained by these two methods were highly consistent: Spearman's correlation coefficient was 0.96 for GST23.2, 0.83 for GST23, 0.92 for GSTU8, 0.87 for UGT71, and 0.87 for UGT74. In general, in plants grown under control conditions, the mRNA levels of these genes were slightly higher in the sensitive cultivars than in the resistant ones. However, the extent of increase in expression of UGT and GST coding genes was significantly higher in the flax cultivars resistant to Al. It is worth noting that we observed the response already after 4 h of Al exposure. Thus, flax can be referred to plants that are characterized by rapid response to Al stress.

GSTs are detoxification enzymes, which catalyze the conjugation of glutathione to electrophilic compounds (Labrou et al., 2015). GSTs are involved in the response of plants to stress, including oxidative stress, and can act as glutathione-dependent peroxidases (Marrs, 1996; Dalton et al., 2009; Rahantaniaina et al., 2013). The exposure of plants to Al results in the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and lipid peroxidation (Gutteridge et al., 1985; Richards et al., 1998; Yamamoto et al., 2001; Jones et al., 2006). The participation of GST in the response of plants to aluminum stress was investigated, and an increase in GST expression was observed under Al stress in the resistant and sensitive to Al maize lines (Cançado et al., 2005), Arabidopsis (Richards et al., 1998; Ezaki et al., 2004), blueberry roots (Inostroza-Blancheteau et al., 2011), and pea roots (Panda and Matsumoto, 2010). We observed that the expression of GST gene family was up-regulated in flax plants under Al exposure, especially in the resistant cultivars. Therefore, defense against the Al toxicity via GST antioxidant activity, probably, is the mechanism of the response of flax plants to aluminum stress. However, for other antioxidative enzymes, which are involved in Al response, such as non-glutathione peroxidase and superoxide dismutase (Ezaki et al., 2000; Boscolo et al., 2003; Du et al., 2010), we did not observe any increase in the expression under Al stress on the basis of our high-throughput sequencing data. We suppose that GSTs play a key role in the oxidative stress defense of flax under Al treatment.

We observed that the expression of UDP-glycosyltransferase genes was also increased under Al exposure in the flax plants. UGTs are involved in the biosynthesis of secondary metabolites, hormone homeostasis, and detoxification of xenobiotics (Ross et al., 2001; Bock, 2016; Le Roy et al., 2016) and participate in the plant stress response (Chong et al., 2002; Langlois-Meurinne et al., 2005; Meissner et al., 2008; von Saint Paul et al., 2011; Li et al., 2015). The alterations in the expression of UGTs under Al exposure were observed in rice (Huang et al., 2009), buckwheat (Yokosho et al., 2014), and maize (Mattiello et al., 2014). In flax, UGTs attract special attention because of their participation in the biosynthesis of lignans—phytoestrogens with antimicrobial, antifungal, antiviral, and antioxidant activity—which have therapeutic effects against human diseases (Dixon, 2004; Pan et al., 2009; Barvkar et al., 2012; Ghose et al., 2014; Imran et al., 2015). UGTs catalyze the glucose conjugation of monolignols that is essential for normal cell wall lignification (Lin et al., 2016). Sensitive to Al rhizotoxicity 1 and 2 (STAR1 and STAR2) genes encode domains of the ABC transporter, which transport UDP-glucose that could modify the cell wall and reduce Al-toxicity (Huang et al., 2009). We suggest that UGTs could also be involved in cell wall modification in response to Al stress in flax. Besides, UGTs are implicated in the detoxification of toxins and ROS secondary metabolites (Simon et al., 2014; Krempl et al., 2016). Therefore, the protection of flax plants from ROS via UGTs could be another possible mechanism of L. usitatissimum resistance to aluminum.

Moreover, on the basis of our high-throughput sequencing data, we performed expression analysis for a number of genes, which are known to participate in Al response in different plant species, such as ALMTs, ABC transporters, STOP1, and aquaporins (Liu et al., 2014; Kochian et al., 2015). We did not observe any significant up-regulation of these genes under Al stress in flax. Probably, the enzymes encoded by these genes do not play key roles in flax resistance to Al. In L. usitatissimum, the detoxification of ROS and cell wall modification via GSTs and UGTs could be the key mechanisms for overcoming Al toxicity.

Conclusion

We identified genes with differential expression under Al exposure in flax plants using high-throughput sequencing and qPCR analysis. We observed increase in the expression of glutathione S-transferase and UDP-glycosyltransferase genes under Al stress. Moreover, the up-regulation of these genes was more pronounced in flax cultivars resistant to Al. However, we did not notice any increase in the expression of aluminum-activated malate transporters, which are involved in one of the most studied mechanisms of plant Al avoidance—the root exudation of organic acid to chelate Al3+. We speculate that GSTs and UGTs are involved in the response of flax to Al stress and suggest that the probable mechanisms for the resistance of flax to aluminum are detoxification of ROS and cell wall modification via GSTs and UGTs.

Author contributions

AD, TR, NB, and NM conceived and designed the work; AD, TR, NK, AZ, AFS, AVS, MF, OY, NB, and NM performed the experiments; AD, GK, AZ, OM, AK, and NM analyzed the data; AD, GK, and NM drafted the work. All the authors revised the work critically for important intellectual content, approved the version to be published, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Funding

This work was financially supported by the Russian Science Foundation, grant 16-16-00114.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank All-Russian Research Institute for Flax for the selection and provision of seeds. This work was performed using the equipment of “Genome” center of Engelhardt Institute of Molecular Biology (http://www.eimb.ru/rus/ckp/ccu_genome_c.php).

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fpls.2016.01920/full#supplementary-material

References

- Arenhart R. A., Bai Y., de Oliveira L. F., Neto L. B., Schunemann M., Maraschin Fdos S., et al. (2014). New insights into aluminum tolerance in rice: the ASR5 protein binds the STAR1 promoter and other aluminum-responsive genes. Mol. Plant 7, 709–721. 10.1093/mp/sst160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barvkar V. T., Pardeshi V. C., Kale S. M., Kadoo N. Y., Gupta V. S. (2012). Phylogenomic analysis of UDP glycosyltransferase 1 multigene family in Linum usitatissimum identified genes with varied expression patterns. BMC Genomics 13:175. 10.1186/1471-2164-13-175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bock K. W. (2016). The UDP-glycosyltransferase (UGT) superfamily expressed in humans, insects and plants: animal-plant arms-race and co-evolution. Biochem. Pharmacol. 99, 11–17. 10.1016/j.bcp.2015.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger A. M., Lohse M., Usadel B. (2014). Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30, 2114–2120. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolsheva N. L., Zelenin A. V., Nosova I. V., Amosova A. V., Samatadze T. E., Yurkevich O. Y., et al. (2015). The diversity of karyotypes and genomes within section syllinum of the Genus Linum (Linaceae) revealed by molecular cytogenetic markers and RAPD analysis. PLoS ONE 10:e0122015. 10.1371/journal.pone.0122015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boscolo P. R., Menossi M., Jorge R. A. (2003). Aluminum-induced oxidative stress in maize. Phytochemistry 62, 181–189. 10.1016/S0031-9422(02)00491-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cançado G. M. A., De Rosa V. E., Fernandez J. H., Maron L. G., Jorge R. A., Menossi M. (2005). Glutathione S-transferase and aluminum toxicity in maize. Funct Plant Biol. 32, 1045–1055. 10.1071/FP05158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caniato F. F., Hamblin M. T., Guimaraes C. T., Zhang Z., Schaffert R. E., Kochian L. V., et al. (2014). Association mapping provides insights into the origin and the fine structure of the sorghum aluminum tolerance locus, AltSB. PLoS ONE 9:e87438. 10.1371/journal.pone.0087438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chong J., Baltz R., Schmitt C., Beffa R., Fritig B., Saindrenan P. (2002). Downregulation of a pathogen-responsive tobacco UDP-Glc:phenylpropanoid glucosyltransferase reduces scopoletin glucoside accumulation, enhances oxidative stress, and weakens virus resistance. Plant Cell 14, 1093–1107. 10.1105/tpc.010436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullis C. A. (1981). DNA sequence organization in the flax genome. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 652, 1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalton D. A., Boniface C., Turner Z., Lindahl A., Kim H. J., Jelinek L., et al. (2009). Physiological roles of glutathione S-transferases in soybean root nodules. Plant Physiol. 150, 521–530. 10.1104/pp.109.136630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dash P. K., Cao Y., Jailani A. K., Gupta P., Venglat P., Xiang D., et al. (2014). Genome-wide analysis of drought induced gene expression changes in flax (Linum usitatissimum). GM Crops Food 5, 106–119. 10.4161/gmcr.29742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day A., Addi M., Kim W., David H., Bert F., Mesnage P., et al. (2005). ESTs from the fibre-bearing stem tissues of flax (Linum usitatissimum L.): expression analyses of sequences related to cell wall development. Plant Biol. (Stuttg). 7, 23–32. 10.1055/s-2004-830462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delhaize E., Ryan P. R., Randall P. J. (1993). Aluminum tolerance in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) (II. aluminum-stimulated excretion of malic acid from root apices). Plant Physiol. 103, 695–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon R. A. (2004). Phytoestrogens. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 55, 225–261. 10.1146/annurev.arplant.55.031903.141729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dmitriev A. A., Kudryavtseva A. V., Krasnov G. S., Koroban N. V., Speranskaya A. S., Krinitsina A. A., et al. (2016). Gene expression profiling of flax (Linum usitatissimum L.) under edaphic stress. BMC Plant Biol. 16(Suppl. 3), 927 10.1186/s12870-016-0927-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du B., Nian H., Zhang Z. (2010). Effects of aluminum on superoxide dismutase and peroxidase activities, and lipid peroxidation in the roots and calluses of soybeans differing in aluminum tolerance. Acta Physiol. Plant 32, 883–890. 10.1007/s11738-010-0476-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ezaki B., Gardner R. C., Ezaki Y., Matsumoto H. (2000). Expression of aluminum-induced genes in transgenic arabidopsis plants can ameliorate aluminum stress and/or oxidative stress. Plant Physiol. 122, 657–665. 10.1104/pp.122.3.657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezaki B., Suzuki M., Motoda H., Kawamura M., Nakashima S., Matsumoto H. (2004). Mechanism of gene expression of Arabidopsis glutathione S-transferase, AtGST1, and AtGST11 in response to aluminum stress. Plant Physiol. 134, 1672–1682. 10.1104/pp.103.037135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan W., Lou H. Q., Yang J. L., Zheng S. J. (2016). The roles of STOP1-like transcription factors in aluminum and proton tolerance. Plant Signal. Behav. 11:e1131371. 10.1080/15592324.2015.1131371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finn R. D., Clements J., Arndt W., Miller B. L., Wheeler T. J., Schreiber F., et al. (2015). HMMER web server: 2015 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, W30–W38. 10.1093/nar/gkv397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Y. B., Dong Y., Yang M. H. (2016). Multiplexed shotgun sequencing reveals congruent three-genome phylogenetic signals for four botanical sections of the flax genus Linum. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 101, 122–132. 10.1016/j.ympev.2016.05.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Y. B., Peterson G. W. (2012). Developing genomic resources in two Linum species via 454 pyrosequencing and genomic reduction. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 12, 492–500. 10.1111/j.1755-0998.2011.03100.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furukawa J., Yamaji N., Wang H., Mitani N., Murata Y., Sato K., et al. (2007). An aluminum-activated citrate transporter in barley. Plant Cell Physiol. 48, 1081–1091. 10.1093/pcp/pcm091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galindo-Gonzalez L., Pinzon-Latorre D., Bergen E. A., Jensen D. C., Deyholos M. K. (2015). Ion Torrent sequencing as a tool for mutation discovery in the flax (Linum usitatissimum L.) genome. Plant Methods 11:19. 10.1186/s13007-015-0062-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Oliveira A. L., Benito C., Prieto P., de Andrade Menezes R., Rodrigues-Pousada C., Guedes-Pinto H., et al. (2013). Molecular characterization of TaSTOP1 homoeologues and their response to aluminium and proton H+ toxicity in bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). BMC Plant Biol. 13:134. 10.1186/1471-2229-13-134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghose K., Selvaraj K., McCallum J., Kirby C. W., Sweeney-Nixon M., Cloutier S. J., et al. (2014). Identification and functional characterization of a flax UDP-glycosyltransferase glucosylating secoisolariciresinol (SECO) into secoisolariciresinol monoglucoside (SMG) and diglucoside (SDG). BMC Plant Biol. 14:82. 10.1186/1471-2229-14-82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godfray H. C., Beddington J. R., Crute I. R., Haddad L., Lawrence D., Muir J. F., et al. (2010). Food security: the challenge of feeding 9 billion people. Science 327, 812–818. 10.1126/science.1185383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goulding K. W. (2016). Soil acidification and the importance of liming agricultural soils with particular reference to the United Kingdom. Soil Use Manag 32, 390–399. 10.1111/sum.12270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabherr M. G., Haas B. J., Yassour M., Levin J. Z., Thompson D. A., Amit I., et al. (2011). Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-Seq data without a reference genome. Nat. Biotechnol. 29, 644–652. 10.1038/nbt.1883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grevenstuk T., Romano A. (2013). Aluminium speciation and internal detoxification mechanisms in plants: where do we stand? Metallomics 5, 1584–1594. 10.1039/c3mt00232b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo J. H., Liu X. J., Zhang Y., Shen J. L., Han W. X., Zhang W. F., et al. (2010). Significant acidification in major Chinese croplands. Science 327, 1008–1010. 10.1126/science.1182570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutteridge J. M., Quinlan G. J., Clark I., Halliwell B. (1985). Aluminium salts accelerate peroxidation of membrane lipids stimulated by iron salts. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 835, 441–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas B. J., Papanicolaou A., Yassour M., Grabherr M., Blood P. D., Bowden J., et al. (2013). De novo transcript sequence reconstruction from RNA-seq using the Trinity platform for reference generation and analysis. Nat. Protoc. 8, 1494–1512. 10.1038/nprot.2013.084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidarabadi M. D., Ghanati F., Fujiwara T. (2011). Interaction between boron and aluminum and their effects on phenolic metabolism of Linum usitatissimum L. roots. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 49, 1377–1383. 10.1016/j.plaphy.2011.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoekenga O. A., Maron L. G., Pineros M. A., Cancado G. M., Shaff J., Kobayashi Y., et al. (2006). AtALMT1, which encodes a malate transporter, is identified as one of several genes critical for aluminum tolerance in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 9738–9743. 10.1073/pnas.0602868103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C. F., Yamaji N., Chen Z., Ma J. F. (2012). A tonoplast-localized half-size ABC transporter is required for internal detoxification of aluminum in rice. Plant J. 69, 857–867. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04837.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C. F., Yamaji N., Mitani N., Yano M., Nagamura Y., Ma J. F. (2009). A bacterial-type ABC transporter is involved in aluminum tolerance in rice. Plant Cell 21, 655–667. 10.1105/tpc.108.064543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huis R., Hawkins S., Neutelings G. (2010). Selection of reference genes for quantitative gene expression normalization in flax (Linum usitatissimum L.). BMC Plant Biol. 10:71. 10.1186/1471-2229-10-71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imran M., Ahmad N., Anjum F. M., Khan M. K., Mushtaq Z., Nadeem M., et al. (2015). Potential protective properties of flax lignan secoisolariciresinol diglucoside. Nutr. J. 14:71. 10.1186/s12937-015-0059-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inostroza-Blancheteau C., Reyes-Diaz M., Aquea F., Nunes-Nesi A., Alberdi M., Arce-Johnson P. (2011). Biochemical and molecular changes in response to aluminium-stress in highbush blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum L.). Plant Physiol. Biochem. 49, 1005–1012. 10.1016/j.plaphy.2011.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson C., Moss T., Cullis C. (2011). Environmentally induced heritable changes in flax. J. Vis. Exp. e2332 10.3791/2332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones D. L., Blancaflor E. B., Kochian L. V., Gilroy S. (2006). Spatial coordination of aluminium uptake, production of reactive oxygen species, callose production and wall rigidification in maize roots. Plant Cell Environ. 29, 1309–1318. 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2006.01509.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinraide T. B. (1991). Identity of the rhizotoxic aluminium species. Plant Soil 134, 167–178. 10.1007/BF00010729 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kishlyan N. V., Rozhmina T. A. (2010). Investigathion of flax (Linum usitatissimum L.) gene poole on resistance to soil acidity. Agric. Biol. 1, 96–103. [Google Scholar]

- Kochian L. V., Piñeros M. A., Liu J., Magalhaes J. V. (2015). Plant adaptation to acid soils: the molecular basis for crop aluminum resistance. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 66, 571–598. 10.1146/annurev-arplant-043014-114822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krasnov G. S., Oparina N. Y., Dmitriev A. A., Kudryavtseva A. V., Anedchenko E. A., Kondrat'eva T. T., et al. (2011). RPN1, a new reference gene for quantitative data normalization in lung and kidney cancer. Mol. Biol. 45, 211–220. 10.1134/S0026893311020129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krempl C., Sporer T., Reichelt M., Ahn S. J., Heidel-Fischer H., Vogel H., et al. (2016). Potential detoxification of gossypol by UDP-glycosyltransferases in the two Heliothine moth species Helicoverpa armigera and Heliothis virescens. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 71, 49–57. 10.1016/j.ibmb.2016.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S., You F. M., Cloutier S. (2012). Genome wide SNP discovery in flax through next generation sequencing of reduced representation libraries. BMC Genomics 13:684. 10.1186/1471-2164-13-684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labrou N. E., Papageorgiou A. C., Pavli O., Flemetakis E. (2015). Plant GSTome: structure and functional role in xenome network and plant stress response. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 32, 186–194. 10.1016/j.copbio.2014.12.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langlois-Meurinne M., Gachon C. M., Saindrenan P. (2005). Pathogen-responsive expression of glycosyltransferase genes UGT73B3 and UGT73B5 is necessary for resistance to Pseudomonas syringae pv tomato in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 139, 1890–1901. 10.1104/pp.105.067223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langmead B., Salzberg S. L. (2012). Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods 9, 357–359. 10.1038/nmeth.1923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen P. B., Geisler M. J., Jones C. A., Williams K. M., Cancel J. D. (2005). ALS3 encodes a phloem-localized ABC transporter-like protein that is required for aluminum tolerance in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 41, 353–363. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02306.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence G. B., Fernandez I. J., Richter D. D., Ross D. S., Hazlett P. W., Bailey S. W., et al. (2013). Measuring environmental change in forest ecosystems by repeated soil sampling: a north american perspective. J. Environ. Q. 42, 623–639. 10.2134/jeq2012.0378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Roy J., Huss B., Creach A., Hawkins S., Neutelings G. (2016). Glycosylation is a major regulator of phenylpropanoid availability and biological activity in plants. Front. Plant Sci. 7:735. 10.3389/fpls.2016.00735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li B., Dewey C. N. (2011). RSEM: accurate transcript quantification from RNA-Seq data with or without a reference genome. BMC Bioinformatics 12:323 10.1186/1471-2105-12-323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y. J., Wang B., Dong R. R., Hou B. K. (2015). AtUGT76C2, an Arabidopsis cytokinin glycosyltransferase is involved in drought stress adaptation. Plant Sci. 236, 157–167. 10.1016/j.plantsci.2015.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin J.-S., Huang X.-X., Li Q., Cao Y., Bao Y., Meng X.-F., et al. (2016). UDP-glycosyltransferase 72B1 catalyzes the glucose conjugation of monolignols and is essential for the normal cell wall lignification in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 88, 26–42. 10.1111/tpj.13229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., Magalhaes J. V., Shaff J., Kochian L. V. (2009). Aluminum-activated citrate and malate transporters from the MATE and ALMT families function independently to confer Arabidopsis aluminum tolerance. Plant J. 57, 389–399. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03696.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., Pineros M. A., Kochian L. V. (2014). The role of aluminum sensing and signaling in plant aluminum resistance. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 56, 221–230. 10.1111/jipb.12162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo W., Brouwer C. (2013). Pathview: an R/Bioconductor package for pathway-based data integration and visualization. Bioinformatics 29, 1830–1831. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma J. F., Shen R., Zhao Z., Wissuwa M., Takeuchi Y., Ebitani T., et al. (2002). Response of rice to Al stress and identification of quantitative trait Loci for Al tolerance. Plant Cell Physiol. 43, 652–659. 10.1093/pcp/pcf081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y., Li C., Ryan P. R., Shabala S., You J., Liu J., et al. (2016). A new allele for aluminium tolerance gene in barley (Hordeum vulgare L.). BMC Genomics 17:186. 10.1186/s12864-016-2551-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magalhaes J. V., Liu J., Guimaraes C. T., Lana U. G., Alves V. M., Wang Y. H., et al. (2007). A gene in the multidrug and toxic compound extrusion (MATE) family confers aluminum tolerance in sorghum. Nat. Genet. 39, 1156–1161. 10.1038/ng2074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangeon A., Pardal R., Menezes-Salgueiro A. D., Duarte G. L., de Seixas R., Cruz F. P., et al. (2016). AtGRP3 is implicated in root size and aluminum response pathways in arabidopsis. PLoS ONE 11:e0150583. 10.1371/journal.pone.0150583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maron L. G., Guimaraes C. T., Kirst M., Albert P. S., Birchler J. A., Bradbury P. J., et al. (2013). Aluminum tolerance in maize is associated with higher MATE1 gene copy number. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 5241–5246. 10.1073/pnas.1220766110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marrs K. A. (1996). The functions and regulation of glutathione S-transferases in Plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 47, 127–158. 10.1146/annurev.arplant.47.1.127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattiello L., Begcy K., da Silva F. R., Jorge R. A., Menossi M. (2014). Transcriptome analysis highlights changes in the leaves of maize plants cultivated in acidic soil containing toxic levels of Al3+. Mol. Biol. Rep. 41, 8107–8116. 10.1007/s11033-014-3709-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meissner D., Albert A., Bottcher C., Strack D., Milkowski C. (2008). The role of UDP-glucose:hydroxycinnamate glucosyltransferases in phenylpropanoid metabolism and the response to UV-B radiation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Planta 228, 663–674. 10.1007/s00425-008-0768-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melnikova N. V., Belenikin M. S., Bolsheva N. L., Dmitriev A. A., Speranskaya A. S., Krinitsina A. A., et al. (2014a). Flax inorganic phosphate deficiency responsive miRNAs. J. Agric. Sci. 6, 156–160. 10.5539/jas.v6n1p156 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Melnikova N. V., Dmitriev A. A., Belenikin M. S., Koroban N. V., Speranskaya A. S., Krinitsina A. A., et al. (2016). Identification, expression analysis, and target prediction of flax genotroph MicroRNAs under normal and nutrient stress conditions. Front. Plant Sci. 7:399. 10.3389/fpls.2016.00399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melnikova N. V., Dmitriev A. A., Belenikin M. S., Speranskaya A. S., Krinitsina A. A., Rachinskaia O. A., et al. (2015). Excess fertilizer responsive miRNAs revealed in Linum usitatissimum L. Biochimie 109, 36–41. 10.1016/j.biochi.2014.11.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melnikova N. V., Kudryavtseva A. V., Zelenin A. V., Lakunina V. A., Yurkevich O. Y., Speranskaya A. S., et al. (2014b). Retrotransposon-based molecular markers for analysis of genetic diversity within the Genus Linum. Biomed. Res. Int. 2014:231589. 10.1155/2014/231589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyasaka S. C., Buta J. G., Howell R. K., Foy C. D. (1991). Mechanism of aluminum tolerance in snapbeans: root exudation of citric Acid. Plant Physiol. 96, 737–743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moustaka J., Ouzounidou G., Baycu G., Moustakas M. (2016). Aluminum resistance in wheat involves maintenance of leaf Ca2+ and Mg2+ content, decreased lipid peroxidation and Al accumulation, and low photosystem II excitation pressure. Biometals 29, 611–623. 10.1007/s10534-016-9938-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muir A. D., Westcott N. D. (2003). Flax: The Genus Linum. London: Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Negishi T., Oshima K., Hattori M., Kanai M., Mano S., Nishimura M., et al. (2012). Tonoplast- and plasma membrane-localized aquaporin-family transporters in blue hydrangea sepals of aluminum hyperaccumulating plant. PLoS ONE 7:e43189. 10.1371/journal.pone.0043189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negishi T., Oshima K., Hattori M., Yoshida K. (2013). Plasma membrane-localized Al-transporter from blue hydrangea sepals is a member of the anion permease family. Genes Cells 18, 341–352. 10.1111/gtc.12041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan J. Y., Chen S. L., Yang M. H., Wu J., Sinkkonen J., Zou K. (2009). An update on lignans: natural products and synthesis. Nat. Prod. Rep. 26, 1251–1292. 10.1039/b910940d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panda S. K., Matsumoto H. (2010). Changes in antioxidant gene expression and induction of oxidative stress in pea (Pisum sativum L.) under Al stress. Biometals 23, 753–762. 10.1007/s10534-010-9342-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piñeros M. A., Magalhaes J. V., Carvalho Alves V. M., Kochian L. V. (2002). The physiology and biophysics of an aluminum tolerance mechanism based on root citrate exudation in maize. Plant Physiol. 129, 1194–1206. 10.1104/pp.002295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Punta M., Coggill P. C., Eberhardt R. Y., Mistry J., Tate J., Boursnell C., et al. (2012). The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 40(Database issue), D290–D301. 10.1093/nar/gkr1065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahantaniaina M. S., Tuzet A., Mhamdi A., Noctor G. (2013). Missing links in understanding redox signaling via thiol/disulfide modulation: how is glutathione oxidized in plants? Front. Plant Sci. 4:477. 10.3389/fpls.2013.00477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards K. D., Schott E. J., Sharma Y. K., Davis K. R., Gardner R. C. (1998). Aluminum induces oxidative stress genes in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Physiol. 116, 409–418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson M. D., McCarthy D. J., Smyth G. K. (2010). edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics 26, 139–140. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers C. M. (1982). The systematics of Linum sect. Linopsis (Linaceae). Plant Syst. Evol. 140, 225–234. 10.1007/bf02407299 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ross J., Li Y., Lim E., Bowles D. J. (2001). Higher plant glycosyltransferases. Genome Biol. 2, REVIEWS3001–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sade H., Meriga B., Surapu V., Gadi J., Sunita M. S., Suravajhala P., et al. (2016). Toxicity and tolerance of aluminum in plants: tailoring plants to suit to acid soils. Biometals 29, 187–210. 10.1007/s10534-016-9910-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki T., Yamamoto Y., Ezaki B., Katsuhara M., Ahn S. J., Ryan P. R., et al. (2004). A wheat gene encoding an aluminum-activated malate transporter. Plant J. 37, 645–653. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2003.01991.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon C., Langlois-Meurinne M., Didierlaurent L., Chaouch S., Bellvert F., Massoud K., et al. (2014). The secondary metabolism glycosyltransferases UGT73B3 and UGT73B5 are components of redox status in resistance of Arabidopsis to Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato. Plant Cell Environ. 37, 1114–1129. 10.1111/pce.12221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tahara K., Hashida K., Otsuka Y., Ohara S., Kojima K., Shinohara K. (2014). Identification of a hydrolyzable tannin, oenothein B, as an aluminum-detoxifying ligand in a highly aluminum-resistant tree, Eucalyptus camaldulensis. Plant Physiol. 164, 683–693. 10.1104/pp.113.222885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venglat P., Xiang D., Qiu S., Stone S. L., Tibiche C., Cram D., et al. (2011). Gene expression analysis of flax seed development. BMC Plant Biol. 11:74. 10.1186/1471-2229-11-74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Saint Paul V., Zhang W., Kanawati B., Geist B., Faus-Kessler T., Schmitt-Kopplin P., et al. (2011). The Arabidopsis glucosyltransferase UGT76B1 conjugates isoleucic acid and modulates plant defense and senescence. Plant Cell 23, 4124–4145. 10.1105/tpc.111.088443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Uexküll H., Mutert E. (1995). Global extent, development and economic impact of acid soils. Plant Soil 171, 1–15. 10.1007/BF00009558 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z., Hobson N., Galindo L., Zhu S., Shi D., McDill J., et al. (2012). The genome of flax (Linum usitatissimum) assembled de novo from short shotgun sequence reads. Plant J. 72, 461–473. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2012.05093.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wojtasik W., Kulma A., Dyminska L., Hanuza J., Czemplik M., Szopa J. (2016). Evaluation of the significance of cell wall polymers in flax infected with a pathogenic strain of Fusarium oxysporum. BMC Plant Biol. 16:75. 10.1186/s12870-016-0762-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wojtasik W., Kulma A., Namysl K., Preisner M., Szopa J. (2015). Polyamine metabolism in flax in response to treatment with pathogenic and non-pathogenic Fusarium strains. Front. Plant Sci. 6:291. 10.3389/fpls.2015.00291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia J., Yamaji N., Ma J. F. (2013). A plasma membrane-localized small peptide is involved in rice aluminum tolerance. Plant J. 76, 345–355. 10.1111/tpj.12296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto Y., Kobayashi Y., Matsumoto H. (2001). Lipid peroxidation is an early symptom triggered by aluminum, but not the primary cause of elongation inhibition in pea roots. Plant Physiol. 125, 199–208. 10.1104/pp.125.1.199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L. T., Qi Y. P., Jiang H. X., Chen L. S. (2013). Roles of organic acid anion secretion in aluminium tolerance of higher plants. Biomed. Res. Int. 2013:173682. 10.1155/2013/173682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokosho K., Yamaji N., Ma J. F. (2011). An Al-inducible MATE gene is involved in external detoxification of Al in rice. Plant J. 68, 1061–1069. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04757.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokosho K., Yamaji N., Ma J. F. (2014). Global transcriptome analysis of Al-induced genes in an Al-accumulating species, common buckwheat (Fagopyrum esculentum Moench). Plant Cell Physiol. 55, 2077–2091. 10.1093/pcp/pcu135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Y., Wu G., Yuan H., Cheng L., Zhao D., Huang W., et al. (2016). Identification and characterization of miRNAs and targets in flax (Linum usitatissimum) under saline, alkaline, and saline-alkaline stresses. BMC Plant Biol. 16:124. 10.1186/s12870-016-0808-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang N., Deyholos M. K. (2016). RNASeq analysis of the shoot apex of flax (Linum usitatissimum) to identify phloem fiber specification genes. Front. Plant Sci. 7:950. 10.3389/fpls.2016.00950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng S. J. (2010). Crop production on acidic soils: overcoming aluminium toxicity and phosphorus deficiency. Ann. Bot. 106, 183–184. 10.1093/aob/mcq134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu H., Wang H., Zhu Y., Zou J., Zhao F. J., Huang C. F. (2015). Genome-wide transcriptomic and phylogenetic analyses reveal distinct aluminum-tolerance mechanisms in the aluminum-accumulating species buckwheat (Fagopyrum tataricum). BMC Plant Biol. 15:16. 10.1186/s12870-014-0395-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.