Abstract

Clostridium perfringens is the most common cause of clostridial myonecrosis (gas gangrene). Polymorphonuclear cells (PMNs) appear to play only a minor role in preventing the onset of myonecrosis in a mouse animal model of the disease (unpublished results). However, the importance of macrophages in the host defense against C. perfringens infections is still unknown. Two membrane-active toxins produced by the anaerobic C. perfringens, alpha-toxin (PLC) and perfringolysin O (PFO), are thought to be important in the pathogenesis of gas gangrene and the lack of phagocytic cells at the site of infection. Therefore, C. perfringens mutants lacking PFO and PLC were examined for their relative cytotoxic effects on macrophages, their ability to escape the phagosome of macrophages, and their persistence in mouse tissues. C. perfringens survival in the presence of mouse peritoneal macrophages was dependent on both PFO and PLC. PFO was shown to be the primary mediator of C. perfringens-dependent cytotoxicity to macrophages. Escape of C. perfringens cells from phagosomes of macrophage-like J774-33 cells and mouse peritoneal macrophages was mediated by either PFO or PLC, although PFO seemed to play a more important role in escape from the phagosome in peritoneal macrophages. At lethal doses (109) of bacteria only PLC was necessary for the onset of myonecrosis, while at sublethal doses (106) both PFO and PLC were necessary for survival of C. perfringens in mouse muscle tissue. These results suggest PFO-mediated cytotoxicity toward macrophages and the ability to escape macrophage phagosomes may be important factors in the ability of C. perfringens to survive in host tissues when bacterial numbers are low relative to those of phagocytic cells, e.g., early in an infection.

Clostridium perfringens is a gram-positive, spore-forming, nonmotile anaerobe that causes a variety of diseases in humans, including gas gangrene (clostridial myonecrosis), enteritis necroticans (Pigbel), acute food poisoning, and antibiotic-associated diarrhea (9, 16, 29). If wounds, which are commonly contaminated by C. perfringens, become anoxic due to disruption of the arterial blood supply, the bacteria can grow and clinical signs of gangrene can appear as soon as 6 h after trauma (34). The infection has all-or-nothing characteristics since, once initiated, the disease spreads rapidly through healthy tissues, leading inevitably to shock and death if not treated. Growth of the bacterium in ischemic tissues in the early stages of the infection seems to be an important factor in determining whether a full gangrene infection will ensue (7). The two main toxins contributing to gas gangrene infections are thought to be alpha-toxin (PLC), a phospholipase C and sphingomyelinase (40), and theta toxin (perfringolysin O [PFO]), a member of the cholesterol-dependent cytolysin family (41).

A hallmark of clinical gas gangrene infections is the lack of phagocytic cells at the site of infection (7). This observation raises an important question. Since a wound would be a site of accumulation of phagocytic cells, how does the relatively small number of C. perfringens cells that infect a wound cause gangrene despite the presence of phagocytic cells of the host immune system, primarily polymorphonuclear cells (PMNs) and, to a lesser extent, monocytes and macrophages? C. perfringens must be able to avoid the bactericidal activity of these phagocytic cells. The fact that gangrene infections develop to a clinically apparent stage signifies that these phagocytic cells often fail to kill C. perfringens efficiently, indicating C. perfringens possesses defense mechanisms against PMN- and macrophage-mediated killing activities.

In an early report, using an unidentified strain of C. perfringens, Mandell established that human PMNs can kill C. perfringens in vitro under both aerobic and anaerobic conditions (20). However, we have recently demonstrated that while depleting the number of PMNs in mice by 97% reduced the time observed for the initiation of a gangrene infection by 6 h, PMN depletion did not significantly affect the survival of mice after 24 h postinfection (unpublished results). In contrast to the results seen with the in vitro assays (20), our in vivo data suggest PMNs play only a minor role in preventing the initiation of a gangrene infection in mice. However, even in the PMN-depleted mice, an infectious dose of ∼1 × 108 C. perfringens strain 13 bacteria was needed to initiate a gangrene infection (unpublished results). The requirement of such a relatively large dose of bacteria needed for infection suggests that the host immune system still plays a role in inhibiting the initiation of a gangrene infection. Possibly, the other primary phagocytic cells of the innate immune system, monocytes/macrophages, play an important role in preventing C. perfringens gangrene infections. Consequently, the interactions of macrophages with C. perfringens have recently become a subject of study by our group (25, 26).

The paucity of phagocytic cells at the site of a gangrene infection is unique to C. perfringens infections and is usually attributed to the cytotoxic effects on phagocytes and upregulation of PMN cytoadherence molecules on endothelial cells by PLC and PFO (7, 36). Purified PFO has been reported to be cytotoxic to PMNs in vitro (4, 37, 38). The cytotoxicity of PLC to leukocytes is less clear. PLC has been reported to be leukotoxic (7, 35, 36), but purified PLC showed little cytotoxicity towards PMNs in an in vitro assay (38), and a Bacillus subtilis strain expressing the plc gene of C. perfringens failed to show any cytotoxicity towards the macrophage cell line SV-BP-1, suggesting that PLC is not cytotoxic to macrophages when acting alone (24). We have previously observed that wild-type C. perfringens bacteria are cytotoxic to macrophages under aerobic conditions (unpublished results) and anaerobic conditions (25). In addition, a Listeria monocytogenes strain and a B. subtilis strain expressing the pfoA gene (which encodes PFO) exhibited cytotoxic effects on J774 macrophages and bone marrow macrophages (17, 28). These results suggest PFO may be more responsible for cytotoxicity towards macrophages than PLC.

Pathogens such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Legionella pneumophila, and Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium enter macrophages and survive by modifying the vacuolar maturation process (1). Other intracellular bacteria, including species of Shigella, Rickettsia, and Listeria, escape the phagosome and replicate in the cytosol (12). C. perfringens shows some similarities to the latter group of pathogens, since it can also escape the phagosome of macrophages (25), but it has yet to be determined if C. perfringens can replicate inside the cytosol of murine macrophages. The mechanism whereby C. perfringens lyses the phagosomal membrane in macrophages to gain access to the cytoplasm has not been identified. Both PFO and PLC, which are membrane-active toxins, may play a role in phagosomal escape. PFO is a cholesterol-dependent cytolysin that oligomerizes to form large pores (20 to 30 nm in diameter) upon contact with cholesterol-containing membranes (15, 27). Strains of L. monocytogenes or B. subtilis engineered to express the pfoA gene of C. perfringens were able to lyse the phagocytic vacuole and replicate in the cytoplasm of J774 cells (17, 28), and it has been suggested that PFO may play a similar role in C. perfringens (28). PLC, possessing phospholipase C and sphingomyelinase activities, could in principal mediate escape from the phagosome of macrophages. However, a B. subtilis strain designed to express the plc gene of C. perfringens (as described above) did not survive in the intracellular environment of the macrophage cell line SV-BP-1 any better than did wild-type B. subtilis, leading the authors to suggest that PLC alone does not mediate phagosomal escape and survival in macrophages (24).

The goal of the experiments described in this report was to identify the respective roles played by PLC and PFO in two important mechanisms in the defense against macrophage-dependent killing of C. perfringens: cytotoxicity of the bacterium towards macrophages, and the ability to mediate escape from the phagosome if the bacterium is phagocytosed by a macrophage. We discovered that PFO plays an important role in both of these events and so may be an important virulence factor in resisting macrophage-mediated killing. Yet, in several previous studies using mutant strains that were unable to produce PLC and/or PFO, PLC was shown to be essential for initiating a gangrene infection when 109 bacteria were injected into mouse muscle tissue, while PFO was shown to play only a minor role, if any, in this infection model (2, 11, 39). Consequently, we wanted to examine the role of PFO in an early stage of a gangrene infection, when the bacterial numbers are few relative to those of phagocytic cells. The ability of C. perfringens to persist in mouse muscle tissues at a relatively low dose (106) in comparison to that needed to cause a full gangrene infection (108 to 109) was determined. Using this variation of the mouse model, we discovered that PFO was as necessary as PLC for persistence of the bacterium in host tissues at the low dose, indicating PFO may play an important role in the early stages of an infection, when the ratio of bacteria to phagocytic cells is low.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Growth conditions for bacterial strains and macrophage cell lines.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. B. subtilis and Escherichia coli were grown in Luria-Bertani medium (10 g of tryptone, 5 g of NaCl, and 5 g of yeast extract per liter). C. perfringens strains were grown in a Coy anaerobic chamber (Coy Laboratory Products) in PGY medium (30 g of Proteose Peptone, 20 g of glucose, 10 g of yeast extract, and 1 g of sodium thioglycolate per liter) (21).

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used in the study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristics | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli | ||

| DH10B | F−mcrA Δ(mrr-hsdRMS-mcrBC) F80d lacZ ΔM15 lacX74 deoR recA1 araD139 (ara, leu)7697 galU galK λ-rpsL endAl nupG | Gibco/BRL Corp. |

| B. subtilis | ||

| JH642 | trpC2 pheA1 | J. Hoch |

| C. perfringens | ||

| Strain 13 | PFO+ PLC+ | C. Duncan |

| DOB3 | PFO− PLC+ | This study |

| PLC- | PFO+ PLC− | A. Okabe (18) |

| DOB4 | PFO− PLC− | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pSM300 | E. coli origin of replication, erythromycin resistance | This study |

| pSM250 | pSM300, 905-bp internal fragment of pfoA | This study |

J774A.1 cells, a macrophage-like cell line, and a highly phagocytic clone derived from J774A.1 cells, J774-33 (25), were used in these experiments. J774 cells were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) with 4.5 g of glucose per liter and l-glutamine (Biowhittaker), 10% (vol/vol) fetal bovine serum (FBS), and 5 mM sodium pyruvate and incubated in 5% CO2 at 37°C.

Plasmid constructs and DNA manipulations.

To create a pfoA mutant, the pfoA gene was amplified by PCR with oligonucleotides ODOB3 (5′-GGAACTGCTAGCATAATTGGAATCCCAG-3′), located 400 bases upstream of the pfoA transcriptional start site, and ODOB2 (5′-GACTAGCTAGCATCAGTTTTTAC-3′), located 29 bases downstream of the pfoA stop codon. The PCR product was then digested with HindIII and SpeI, giving a 905-bp fragment internal to the pfoA gene, which was ligated to pSM300, digested with HindIII and XbaI, to form pSM250. pSM300 is a plasmid carrying an ermBP gene, which confers erythromycin resistance on both E. coli and C. perfringens, but an origin of replication that functions only in E. coli. Early-stationary-phase C. perfringens strain 13 cells were subjected to electroporation in a 2-mm cuvette with 50 μg of pSM250 and grown on PGY plates with 30 μg of erythromycin/ml. Three erythromycin-resistant colonies were isolated, and all exhibited a PFO− phenotype on sheep blood agar plates (i.e., lacked the inner zone of hemolysis characteristic of C. perfringens). All subsequent work was done with one of these isolates, DOB3. To make a plc pfoA mutant, a pfoA gene disruption was introduced into strain PLC-, a plc derivative of C. perfringens strain 13 (obtained from A. Okabe [18]), as described above for the pfoA strain. Transformants were plated on PGY plates containing chloramphenicol (strain PLC- is chloramphenicol resistant) and erythromycin. Several chloramphenicol-erythromycin-resistant colonies were seen; one of these (DOB4) was characterized further. Cells of strain DOB4 were plated on sheep blood agar plates, and the colonies exhibited a complete lack of both the inner (i.e., PFO) and outer (i.e., PLC) zones of hemolysis. The plc mutant obtained from A. Okabe (18) was plated on sheep blood agar and egg yolk agar plates to confirm the lack of PLC activity.

Southern hybridization analysis.

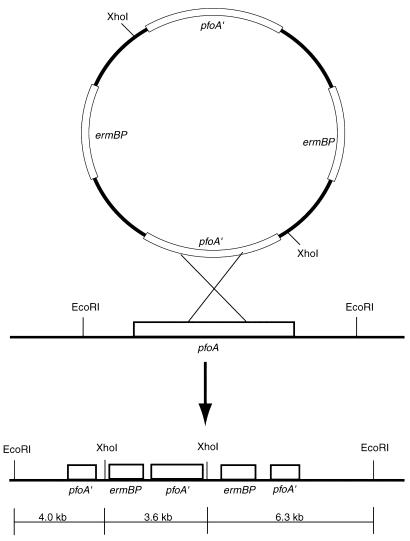

Southern hybridization analysis was done on the pfoA and plc pfoA mutants. Chromosomal DNA from the wild-type and pfoA strains was isolated and digested with EcoRI or XhoI and EcoRI. Digests were run on a 0.8% agarose gel and transferred to a nylon membrane (30). Membranes were hybridized with the internal pfoA fragment from pSM250 or with an ermBP gene probe. Probes were labeled and hybridized according to the protocol of the NEBlot Phototope kit (New England BioLabs). After EcoRI digestion, the pfoA gene probe was predicted to hybridize to a 10.3-kb fragment (i.e., a 6.7-kb chromosomal region plus 3.6 kb for pSM300). Instead, the probe hybridized to a ∼13-kb fragment. One explanation for the larger-than-predicted hybridization band was that the plasmid integrated as a dimer (Fig. 1). Therefore, we performed a second set of restriction digests with EcoRI and XhoI and used an ermBP-specific probe. If pSM250 integrated as a dimer, the ermBP probe would be predicted to hybridize to bands of 3.6 and 6.3 kb in size (Fig. 1). This was the pattern observed, indicating pSM250 had integrated as a dimer and disrupted the chromosomal pfoA gene.

FIG. 1.

Schematic diagram illustrating the integration event of pSM250 into the chromosome of the pfoA gene of C. perfringens strains 13 and PLC-. Southern blot analysis showed pSM250 integrated into the chromosome in the doublet form, illustrated in the figure. EcoRI and XhoI fragments used for the Southern hybridization analysis are shown at the bottom of the figure.

PFO assays.

The pfoA and plc pfoA mutant strains of C. perfringens were grown to stationary phase, and the supernatants were collected, filtered, and used to measure PFO production. Red blood cell buffer (2 mM EDTA, 20 mM dithiothreitol, 64 mM KH2PO4, 156 mM NaCl; pH 6.8) containing 50% red blood cells was added to an equal volume of filtered supernatant. The mixture was incubated at 37°C for 30 min under anaerobic conditions. Reactions were centrifuged at 250 × g for 5 min. A hemolytic unit was defined as the difference in the absorbance at 550 nm between the sample and blank per microgram of protein present in each sample. Protein assays, using the Bio-Rad protein assay kit, were performed on each sample.

Transmission electron microscopy.

To determine if mutants lacking PFO or PLC were capable of escaping the phagosome of macrophages, transmission electron microscopy was performed as previously described (25). Briefly, J774-33 cells or peritoneal macrophages were grown in DMEM in 50-ml tissue culture-treated flasks. C. perfringens strains were grown in PGY medium to mid-log phase and then washed three times in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to remove extracellular toxins. The bacteria were added at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10:1 to the macrophage culture and incubated at 37°C for 60 or 120 min, as indicated in each experiment. The infected macrophages were washed with PBS and then fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde in PBS for 5 min, pelleted by a 1-min spin at 200 × g, and left in the fixative for 1 to 2 h at room temperature. The pellets were then processed as previously described (23). Samples were viewed and photographed on a JEOL 2000EX electron microscope at 60 kV. Between 30 and 42 intracellular bacteria were examined for each sample and were judged to be inside the phagosome or in the cytoplasm. Some intracellular bacteria appeared to be in partially degraded phagosomes, and these were scored as being in phagosomes.

Survival of C. perfringens cells incubated with mouse peritoneal macrophages.

Thioglycolate-elicited peritoneal macrophages were isolated from C3Heb/Fe mice as previously described (22) and transferred to 24-well tissue culture plates. Nonadherent cells were washed off with medium C (RPMI 1640 with 10% FBS, 10 mM HEPES buffer, 0.05 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 100 U of penicillin/ml, and 100 μg of streptomycin/ml), and adherent cells were incubated overnight in medium C in 5% CO2 at 37°C. Each well of the 24-well tissue culture plates contained 6 × 105 macrophages. Macrophages were washed two times with, and incubated in until infected, DMEM with 4.5 g of glucose and l-glutamine per liter, 10% (vol/vol) FBS, and 5 mM sodium pyruvate. After growth in PGY, log-phase C. perfringens cells were washed three times in PBS and added at an MOI of ∼1:1 to aerobically treated macrophages and at an MOI of 0.5:1 to anaerobically treated macrophages. Lower MOIs were used for the anaerobic conditions because higher numbers were found to be rapidly lethal to the macrophages under anaerobic conditions. Plates containing macrophages were incubated either aerobically or anaerobically in 5% CO2 at 37°C during the entire assay. For anaerobic assays, plates with macrophages were incubated in an anaerobic chamber 2 h prior to infection to ensure anaerobic conditions. The macrophages were lysed at increasing times postinfection, and the surviving bacteria were diluted and plated on PGY medium and incubated under anaerobic conditions. Triton X-100 was added to the wells at a final concentration of 0.02% for 1 h to lyse the macrophages. The results of samples taken at 1 and 2 h are not shown below in Fig. 2 due to an experimental artifact in which the C. perfringens cells became temporarily sensitive to the effects of the 0.02% Triton X-100 added to the wells to lyse the macrophages (unpublished results).

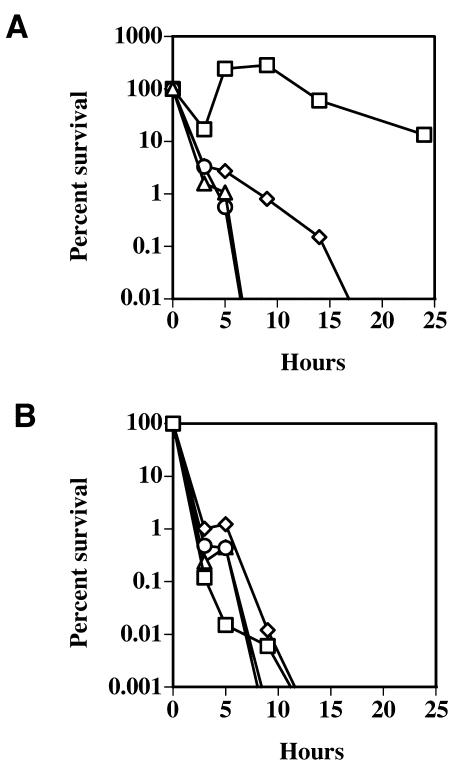

FIG. 2.

(A) Survival of C. perfringens strains incubated with fluid thioglycolate-elicited mouse peritoneal macrophages, with an MOI of 1:1. (B) Survival of C. perfringens strains incubated under aerobic conditions in DMEM cell culture medium in the absence of macrophages, with an inoculum of ∼1.5 × 106 bacteria/well. Squares, strain 13; triangles, DOB3; circles, PLC-; diamonds, DOB4. A representative experiment from one of at least three independent experiments is shown. The values are shown as percent survival, beginning with 100% of the inoculum at 0 h.

C. perfringens-dependent cytotoxicity towards J774 and mouse peritoneal macrophages.

To determine if C. perfringens strains unable to produce PLC and/or PFO could secrete cytotoxic proteins into the growth medium, cultures of C. perfringens were grown for 18 h in PGY medium. After growth in PGY, cell-free supernatants from each culture were obtained by centrifugation of the cells and filtering the supernatants through a 0.22-μm-pore-size filter. Cytotoxicity of the supernatants towards J774 cells was determined using the Cytotox 96 cytotoxicity assay (Promega) as previously described (25). J774 cells were rinsed with DMEM and diluted to a final concentration of 5 × 104 cells per ml, and 150 μl of the cell suspension was added to each experimental well in a 96-well tissue culture plate. After 24 h of incubation of the J774 cells in 5% CO2 at 37°C, 30 μl of bacterial growth medium supernatant was added to each well and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release by the macrophages was measured as described for the Cytotox 96 cytotoxicity assay. Samples were then processed as described in the Cytotox 96 cytotoxicity assay instructions, and the absorbance at 570 nm was measured using a SpectraMax 340 96-well plate reader (Molecular Devices). The total protein levels in the supernatants were determined using the Bio-Rad protein assay kit, and the percent lysis values shown below in Fig. 3 were adjusted to account for differences in total protein in the supernatants. Whole bacterial cell-dependent cytotoxicity towards J774-33 and mouse peritoneal macrophages was measured in a similar fashion. J774-33 cells and mouse peritoneal macrophages (harvested from mice as described above) were added to 96-well tissue culture plates at a final concentration of 5 × 104 cells per ml. Macrophages were grown overnight in 5% CO2 at 37°C. C. perfringens was prepared from mid-logarithmic-phase cultures as described above and added at the MOIs indicated below (see Fig. 4). Macrophages were infected for 5 h with the bacteria, at which time the samples were processed as described above.

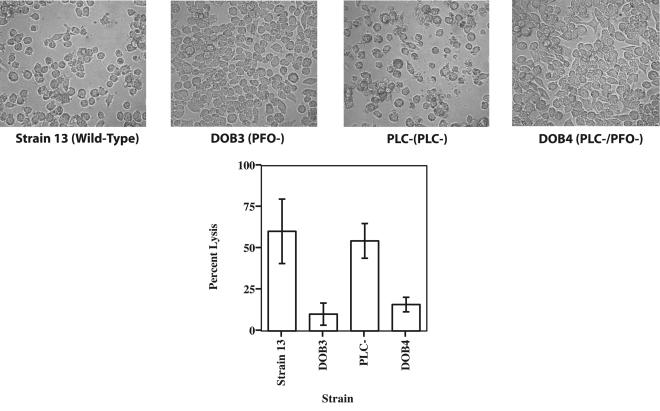

FIG. 3.

(Top) Representative images of macrophages incubated for 24 h with supernatants from the cultures listed below each image. Magnification, ×250. (Bottom) Cytotoxicity of cell-free supernatants from cultures grown with the C. perfringens strain indicated. J774 macrophages were incubated with 30 μl of culture supernatant for 24 h. Cytotoxicity was determined using the Cytotox 96 assay kit. The values are shown as percent lysis, in which the amount of LDH released in wells with treated macrophages was compared to that in control wells in which all of the macrophages had been deliberately lysed. The values shown are the means and standard deviations of quadruplicate samples from three independent experiments.

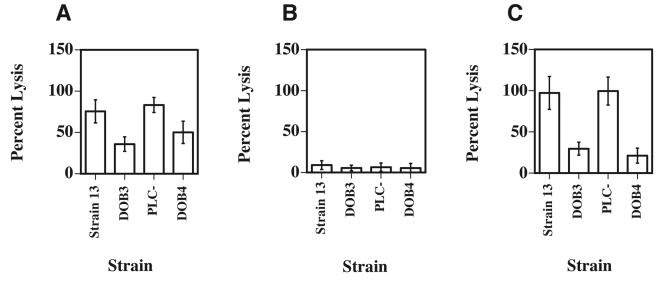

FIG. 4.

C. perfringens whole-cell-dependent cytotoxicity towards macrophages after 5 h of incubation under aerobic conditions. (A) C. perfringens-dependent cytotoxicity towards J774-33 cells incubated with the indicated strains at an MOI of 1:1. (B and C) C. perfringens-dependent cytotoxicity towards mouse peritoneal macrophages incubated with the indicated strains at an MOI of 1:1 (B) or 10:1 (C). Cytotoxicity was determined using the Cytotox 96 assay kit. The values are shown as percent cytotoxicity, in which the amount of lysis that occurred in wells with treated macrophages was compared to that in control wells, in which all of the macrophages had been deliberately lysed. The means and standard deviations of at least three independent experiments performed on quadruplicate samples are shown.

Persistence of C. perfringens in vivo in mouse muscle tissues.

Female BALB/c mice were used for the in vivo survival experiments. Mid-logarithmic-phase C. perfringens cells were injected into the femoral muscle of the left leg at ∼106 bacteria per mouse. At the indicated time points, the mice were euthanized and the left hind leg was removed. The femoral muscle was then dissociated using a metal sieve to release the bacteria from the muscle. The bacterial suspensions were diluted and plated on PGY medium under anaerobic conditions to determine the number of CFU. Six mice were used for each time point in the experiment.

To deliver a lethal dose of C. perfringens, mice were treated as described above and injected in the femoral muscle with ∼1 × 109 bacteria per mouse. Once the onset of gangrene was observed, the mice were euthanized to minimize any unnecessary suffering in accordance with humane animal care practices. Mice that did not show signs of gangrene were euthanized 36 h after the start of the experiment. Experimental protocols involving mice were examined and approved by the Virginia Tech Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

RESULTS

Both PFO and PLC are necessary for the persistence of C. perfringens in the presence of mouse peritoneal macrophages.

To determine if PFO, PLC, or both toxins are necessary for the survival of C. perfringens in the presence of macrophages under aerobic and anaerobic conditions, we created PFO- and PLC-deficient mutants of strain 13 (see Materials and Methods). PFO activity in the pfoA and plc pfoA mutant strains was measured by using filtered supernatants from stationary-phase cultures and testing for their ability to lyse sheep red blood cells (Table 2). The pfoA mutant strain, DOB3, retained 0.96% of the wild-type PFO activity, while the plc pfoA mutant strain, DOB4, retained 0.02% of the wild-type PFO activity (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

PFO activity in C. perfringens strainsa

| Strain | Phenotype | Hemolytic units | % activity relative to strain 13 (wild type) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strain 13 (wild type) | PFO+/PLC+ | 0.1842 ± 0.01 | 100 |

| DOB3 | PFO−/PLC+ | 0.00176 ± 0.000045 | 0.96 |

| DOB4 | PFO−/PLC− | 0.000038 ± 0.0000034 | 0.02 |

PFO activity was defined as the ability of C. perfringens strains to lyse sheep red blood cells, as determined by measuring the release of hemoglobin. A hemolytic unit is the difference in the absorbance at 550 nm between the sample and blank per microgram of protein present in each sample. Results shown are the mean (± standard deviation) of quadruplicate samples measured in each of three independent experiments.

We used fluid thioglycolate-elicited peritoneal macrophages to determine if C. perfringens mutants could survive in the presence of bactericidal primary macrophages. The mouse peritoneal macrophages were infected with C. perfringens under aerobic conditions, and bacterial survival in the presence of the macrophages was determined (Fig. 2). C. perfringens is a large, nonmotile bacterium which settles onto the bottom of the wells in a few minutes and makes contact with the macrophages without external force (i.e., centrifugation) being applied (25). The macrophages then either phagocytose and kill the bacterium or the bacterium is able to persist and sometimes grow under these conditions. The overall bacterial numbers in each well were determined as described in Materials and Methods. In the presence of peritoneal macrophages, wild-type C. perfringens strain 13 survived and actually grew to ∼250% of the level of the original inoculum in the first 9 h, before declining to ∼15% of the inoculum at 24 h (Fig. 2A). However, when peritoneal macrophages were incubated with the pfoA and plc mutant strains of C. perfringens, a marked decrease in bacterial survival was seen (Fig. 2A). The plc pfoA mutant strain showed an intermediate level of survival that was still 2 to 3 logs less than that shown by the wild-type strain. (The higher survival rate seen with the plc pfoA mutant strain in comparison to the single mutant strains may have been due to an increased level of survival in DMEM even in the absence of macrophages [Fig. 2B], which occurred for unknown reasons.) Overall, these results suggest that both PFO and PLC are needed for the survival of C. perfringens in the presence of mouse peritoneal macrophages. When the C. perfringens strains were incubated aerobically in culture medium (DMEM) alone, all the strains except for the plc pfoA mutant strain died by 24 h, and the plc pfoA mutant strain had less than 0.0001% survival (Fig. 2B).

Peritoneal macrophages were also infected with the wild-type and mutant strains of C. perfringens under anaerobic conditions. Whether in the presence or absence of macrophages, all the bacterial strains grew exponentially and the macrophages were completely lysed by 5 h after infection (unpublished results).

PFO is largely responsible for the cytotoxicity towards J774 and mouse peritoneal macrophages under aerobic conditions.

Purified PFO has been shown to be cytotoxic towards human PMNs (4, 38), and we have observed significant cytotoxicity towards J774 and mouse peritoneal macrophages by using purified PFO obtained from R. Tweten (unpublished results). PLC has been reported to exhibit cytotoxic effects on PMNs (7, 36) but not to certain macrophage cell lines (24). To determine the role of PFO and PLC in C. perfringens-mediated cytotoxicity towards macrophages, we used cell-free supernatants from the wild-type strain and compared them to supernatants obtained from the mutant strains in cytotoxicity assays with J774 cells (Fig. 3). The Cytotox 96 assay measures release of the cytoplasmic enzyme LDH from permeabilized or lysed cells. After 24 h of incubation, both the wild-type and the plc mutant strain supernatants exhibited ∼3.5 times the level of cytotoxicity as did the pfoA and plc pfoA mutant strain supernatants (Fig. 3), indicating that PFO was an important factor in cytotoxicity, but PLC was not. J774 cells exposed to the PFO-containing supernatants frequently exhibited a rounded-up morphology and detached from the bottom of the wells (Fig. 3, top images), providing additional evidence of cytotoxicity by PFO.

To determine if whole cells of C. perfringens were cytotoxic to J774-33 cells and mouse peritoneal macrophages, we incubated the macrophages with wild-type C. perfringens cells and strains that lacked PFO, PLC, or both toxins for 5 h at an MOI of 1:1 and compared the levels of cytotoxicity (Fig. 4A and B). J774-33 cells were more sensitive to C. perfringens-dependent cytotoxicity than were peritoneal macrophages at the same MOI (compare Fig. 4A to B). For J774-33 cells, the wild-type C. perfringens cells, and the plc mutant strain were about 1.5 to 2 times as cytotoxic as the pfoA and plc pfoA mutant strains (Fig. 4A). Since the peritoneal macrophages showed very little cell lysis when the MOI was 1:1 (Fig. 4B), we increased the MOI to 10:1 and observed significant levels of cytotoxicity (Fig. 4C), with the wild-type and plc mutant strains exhibiting three to four times the level of cytotoxicity as did the pfoA or plc pfoA mutant strains, which lack PFO. Together, these results indicate that PFO is the toxin most responsible for the C. perfringens-dependent cytotoxicity seen with infected macrophages.

Both PFO and PLC mediate escape from the phagosome of J774-33 cells and mouse peritoneal macrophages.

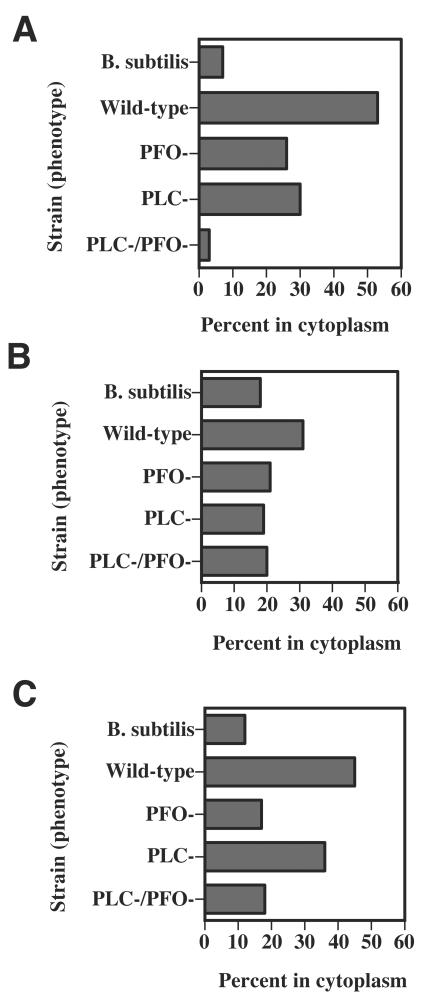

To determine if PFO and/or PLC are involved in the ability of C. perfringens to escape the phagosome of J774-33 cells and mouse peritoneal macrophages, we tested the wild-type and mutant strains for their ability to lyse the phagosomal membrane and enter the cytoplasm after 1 h of incubation with the macrophages. J774A.1 cultures contain a mixture of clones, most of which do not readily phagocytose C. perfringens or other gram-positive bacteria (25). Therefore, we used one of these clones, J774-33, in these experiments. The J774-33 clone was used because it exhibits a high frequency of phagocytosis of C. perfringens (25), its clonal nature means there is a homogeneous response to the addition of C. perfringens, and the receptors used to phagocytose C. perfringens have been identified using this clone (26). Electron micrographs of infected cells were examined, and the number of intracellular bacteria that were either in the phagosome or in the cytoplasm was determined. The results are reported as the percentage of all intracellular bacteria that were clearly identified as being in the cytoplasm. Representative micrographs illustrating wild-type C. perfringens in the cytoplasm and in phagosomes of J774-33 and peritoneal macrophages are shown in Fig. 5. In J774-33 cells, we found that 53% of wild-type C. perfringens strain 13 cells were in the cytoplasm (Fig. 6A). In contrast, we observed that 26 to 28% of intracellular mutant pfoA and plc cells were able to escape the phagosome (Fig. 6A). However, with the plc pfoA mutant strain, only ∼3% of the intracellular bacteria were found in the cytoplasm (Fig. 6A). As a control, we incubated the J774-33 cells with the nonpathogenic bacterium B. subtilis, which cannot efficiently escape the phagosome of J774-33 cells (25). Only 7% of the intracellular B. subtilis bacteria were determined to be in the cytoplasm, using the same electron microscopy methods used for C. perfringens (Fig. 6A).

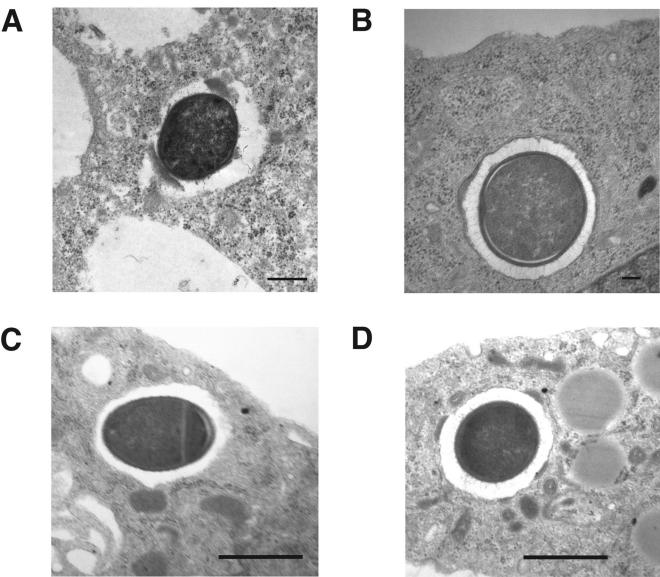

FIG. 5.

Transmission electron microscopy images of J774-33 cells and mouse peritoneal macrophages infected with C. perfringens strain 13. Macrophages were infected for 60 min, fixed, and processed for electron microscopy. (A and B) C. perfringens in the cytoplasm (A) and in the phagosome (B) of J774-33 cells. (C and D) C. perfringens in the cytoplasm (C) and in the phagosome (D) of mouse peritoneal macrophages. Note the presence of a phagosomal membrane around the bacteria in panels B and D. The clear zones around the intracellular bacteria in panels A and C are not associated with a phagosomal membrane. These clear areas have been seen previously with intracellular C. perfringens (25) and may represent the presence of a polysaccharide capsule on strain 13 (26). Magnification: (A and C) ×10,000; (B) ×15,000; (D) ×7,500.

FIG. 6.

(A) Percentage of intracellular C. perfringens bacteria that were determined to be in the cytoplasm of J774-33 macrophages by using electron microscopy (see Materials and Methods). Bacteria clearly lacking a phagosomal membrane around them were scored as being in the cytoplasm of the cells. See Fig. 5A for an example. (B and C) Percentage of intracellular C. perfringens bacteria that were determined to be in the cytoplasm of mouse peritoneal macrophages. Bacteria clearly lacking a phagosomal membrane around them were scored as being in the cytoplasm of the cells. See Fig. 5C for an example. The macrophages in panels A and B were incubated with C. perfringens bacteria for 1 h, while panel C shows results from peritoneal macrophages incubated with the bacteria for 2 h before the cells were fixed and processed for electron microscopy.

After 1 h of incubation with peritoneal macrophages, the percentage of wild-type and mutant bacteria that escaped the phagosome of mouse peritoneal macrophages was lower than that seen in J774-33 cells (compare Fig. 6B to A). Since the survivability of wild-type C. perfringens, in comparison to the mutants, increased with time during incubation with peritoneal macrophages (Fig. 2A), we wanted to determine if phagosomal escape efficiency was higher at a later time. Therefore, we increased the time of incubation with the peritoneal macrophages to 2 h before fixing and examining the cells under the electron microscope. The results are shown in Fig. 6C. After 2 h of incubation, the wild-type strain was able to escape the phagosome at 2.5 to 3.5 times the efficiency seen with the pfoA mutant, plc pfoA mutant, and B. subtilis strains. The plc mutant strain was able to escape the phagosome at ∼2 times the efficiency as the other mutant strains and B. subtilis (Fig. 6C). These results suggest that PFO plays a somewhat more important role in phagosomal escape than does PLC when the bacteria are phagocytosed by peritoneal macrophages.

PLC and PFO are necessary for survival of C. perfringens in vivo at sublethal doses.

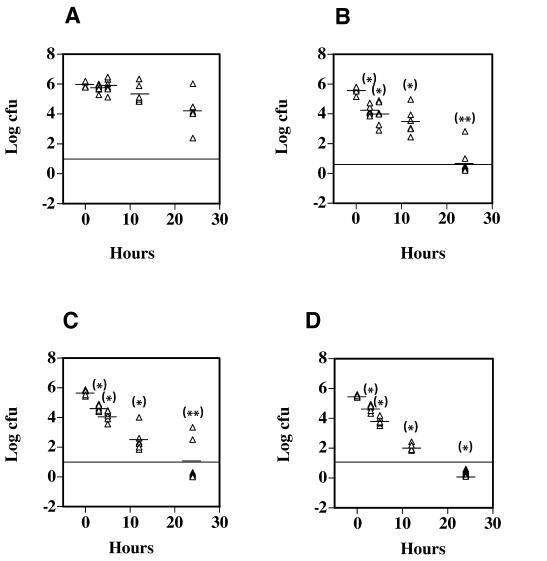

PFO has been shown to be cytotoxic to PMNs in in vitro assays (4, 38). The results we have described so far indicate that PFO also plays an important role in resistance to macrophage-mediated killing of C. perfringens, cytotoxicity towards macrophages, and the ability to escape the phagosome of macrophages. Yet, in several previous reports, PFO has not been demonstrated to play an important role in the initiation of a gangrene infection when high doses (∼1 × 109) of bacteria were injected into the hind leg muscles of mice (2, 11, 39). Our hypothesis is that C. perfringens interacts with tissue macrophages (and PMNs) in the earliest stages of a gangrene infection in humans and resists being killed by these macrophages. We wanted to simulate the early stages of a human C. perfringens infection by using in vivo conditions in the mouse model in which the ratio of bacteria to phagocytes was low, as would be expected to occur in the initial stages of a human infection. Therefore, we used infectious doses (106) that were 100- to 1,000-fold lower than those needed to initiate a gangrene infection (108 to 109) and, instead of looking for the onset of gangrene symptoms, we examined the survival rates of wild-type and mutant C. perfringens strains in mouse tissue. Mice were injected in the femoral muscle with the wild-type and mutant strains, and the surviving bacteria in the muscle tissue were measured over a period of 24 h (see Materials and Methods). The results are shown in Fig. 7. After 24 h, 5% of the initial inoculum of wild-type C. perfringens was still viable (Fig. 7A). This survival rate was ∼1,000-fold higher than that exhibited by the pfoA and plc mutant strains (compare Fig. 7A to B and C) at 24 h. The plc pfoA mutant strain was even more severely limited in its ability to survive in vivo, since no CFU could be detected in the tissues of any mice after 24 h of infection (Fig. 7D). These results indicate that both PFO and PLC are needed for persistence in mouse tissues when C. perfringens is delivered in sublethal doses and that these toxins provide an additive survival effect to C. perfringens. Additional experiments have shown that wild-type C. perfringens can be detected in mouse muscle tissue up to 72 h after infection with 106 bacteria (unpublished results).

FIG. 7.

In vivo survival of C. perfringens injected into the hind leg muscles of mice. The strains injected were strain 13 (A), DOB3 (B), PLC- (C), and DOB4 (D). Thirty-six mice were injected in the left femoral muscle with 106 bacteria/mouse, and six mice were sacrificed at each time point shown. Each triangle represents the number of CFU obtained from one mouse. Dashes represent the mean value of the number of CFU recovered from the six mice analyzed at each time point indicated. The horizontal line represents the lowest level of detection, and values shown below the line indicate no CFU were detected in that mouse. Asterisks above each group represent the statistical difference between the means of mice injected with wild-type C. perfringens (A) at each time indicated and the corresponding mutant strain at the same time interval using the two-tailed t test. *, P ≤ 0.0001; **, P ≤ 0.0025.

As a control, we injected mice with high doses (109 bacteria per mouse) of the wild-type, pfoA mutant, plc mutant, and plc pfoA mutant strains of C. perfringens to ensure that our mutant phenotypes were consistent with those reported in previously published studies (2, 3, 11, 39). All mice injected with the wild-type and pfoA mutant strains of C. perfringens showed clear signs of gangrene between 7 and 12 h postinfection (zero survivors of five infected in both groups [mice showing clear signs of gangrene were euthanized, in accordance with humane animal care practices]). Mice injected with the plc and plc pfoA mutant strains did not develop signs of gangrene (five survivors of five infected in both groups). These results are similar to those reported by other groups, in which PLC was needed to cause a gangrene infection in the mouse model when high doses of bacteria were administered to the mice (2, 3, 11, 39).

DISCUSSION

The primary host defense against C. perfringens in the earliest stages of a posttraumatic infection is likely to be the phagocytic cells of the innate immune system, mainly PMNs and monocytes/macrophages. In the later stages of infection, when the bacteria have multiplied to the extent that a clinical case of gangrene is evident, there is a profound lack of phagocytes in the immediate vicinity of the bacteria (7). A lack of oxygen in the wound area probably also plays an important role in the growth of the anaerobic C. perfringens, since gangrene infections usually begin in hypoxic tissues (34). The lack of oxygen is not a barrier to PMN- and macrophage-dependent bactericidal functions, since both cell types have well-documented bactericidal activities under anaerobic conditions (19, 26, 33). Therefore, resistance to phagocyte-mediated killing seems to be an important factor in the course of a gangrene infection. Bacterial numbers are probably low in the beginning, but bacterial growth in ischemic tissues leads to the development of a clinical case of gangrene. Mandell demonstrated that human PMNs are capable of killing an unidentified strain of C. perfringens under aerobic and anaerobic conditions (20). However, we have recently shown that depleting PMNs by 97% did not significantly affect the survival rate when mice were challenged with C. perfringens in the mouse gangrene model (unpublished results). The mechanism of resistance to PMN-mediated killing is still unknown, although PFO and PLC have been reported to be cytotoxic and disrupt effective chemotaxis by PMNs (4, 7, 35, 36, 38). The absence of a PMN-mediated effect that we observed in initiation of a gangrene infection was remarkable in that gangrene symptoms were still not seen in the PMN-depleted mice unless 108 C. perfringens bacteria were injected (unpublished results). Therefore, it's possible that monocytes and macrophages, the other phagocytic cells of the innate immune system, play a role in inhibiting the growth of C. perfringens in host tissues.

In a previous report, we demonstrated that C. perfringens could persist in the presence of J774-33 macrophages and could escape the phagosome in both J774-33 and peritoneal macrophages (25). In this report, we examined the roles of PFO and PLC in C. perfringens interactions with macrophages in vitro and survival of the bacterium in mouse tissues in vivo. When the C. perfringens strains were incubated in DMEM cell culture medium in the absence of macrophages under aerobic conditions, the bacteria died at an exponential rate (Fig. 2B). In fact, wild-type C. perfringens bacteria survived better in the presence of peritoneal macrophages than they did alone (compare Fig. 2A to B). One explanation for these results could be that the macrophages lower the oxygen concentration in the wells by respiration and other oxygen-utilizing functions, thereby allowing the anaerobic C. perfringens to grow in the extracellular environment. However, the observation that the mutant and wild-type strains survived at very different efficiencies in the presence of macrophages (Fig. 2A), yet died at similar rates in the absence of macrophages (Fig. 2B), suggests this explanation could not account for the majority of C. perfringens-dependent resistance to macrophage killing.

In order to determine what factors were responsible for the resistance to macrophage-mediated killing seen in the wild-type strain (Fig. 2A), we examined the role of PLC and PFO in mediating the cytotoxic effects on macrophages. We used cell-free supernatants from the wild-type and mutant strains as a source of secreted toxins and found that the wild-type and plc mutant strain supernatants, which contained PFO, exhibited significantly more cytotoxicity towards J774 cells after 24 h of incubation than did the PFO− strains (Fig. 3). The assay used to measure cytotoxicity, the Cytotox 96 assay, measures the release of the cytoplasmic enzyme LDH from either permeabilized or lysed (i.e., dead) cells. PFO forms large pores in the cytoplasmic membrane (41, 42), which may allow the release of LDH but not kill the cell. However, the images of the macrophages treated with PFO-containing supernatants showed significant rounding up and detachment of the cells, indicating cell death was occurring (Fig. 3, top images). We also incubated C. perfringens bacteria with J774-33 and peritoneal macrophages and observed that PFO-producing strains were more cytotoxic than those lacking PFO (Fig. 4). Together with the data from cell-free supernatants, these results suggest PFO is the primary mediator of cytotoxicity towards macrophages.

We have previously established that C. perfringens cells have the ability to escape the phagosome of J774-33 and peritoneal macrophages (25). Since phagosomal escape into the cytoplasm would be an effective means of avoiding the bactericidal functions of macrophages, we determined whether the pfoA and plc mutant strains of C. perfringens could escape the phagosome as efficiently as the wild-type strain. With J774-33 cells infected for 1 h, we found that both PFO and PLC were needed for phagosomal escape and that they worked in an additive fashion, since the plc pfoA mutant strain had lower levels of phagosomal escape than the single mutants (Fig. 6A). In peritoneal macrophages infected for 1 h, the wild-type strain did not show as sizeable a difference in the ability to escape the phagosome compared to that of the mutant strains as was seen with the J774-33 cells (Fig. 6A and B). If bacterial survival rates and phagosomal escape are linked, this suggested to us that a time greater than 1 h after the addition of C. perfringens might show more differences between the wild-type and mutant strains in escaping the phagosome of peritoneal macrophages. Therefore, we incubated the bacteria with the macrophages for 2 h before fixing the cells and examining them in the electron microscope. Here, the wild-type and pfoA mutant strains did show increased levels of phagosomal escape compared to the 1-h incubation, while the pfoA and plc pfoA mutant strains of C. perfringens and the B. subtilis control showed similar or lower (B. subtilis) levels of phagosomal escape (Fig. 6C). These results suggest PFO may play a more important role in phagosomal escape than PLC in peritoneal macrophages, but not in J774-33 cells. Unfortunately, invasion assays with C. perfringens and macrophages have not been successful, probably due to PFO-dependent leakiness of the macrophage cytoplasmic membrane to antibiotics (27). This makes it difficult to determine the precise role that phagosomal escape plays in the ability of C. perfringens to resist being killed by macrophages.

It is, perhaps, not surprising that C. perfringens can escape the phagosome of macrophages via the membrane disruption effects of PFO and PLC. Portnoy and coworkers suggested such a role for PFO, based on experiments where B. subtilis was engineered to express the pfoA gene of C. perfringens (28). L. monocytogenes and C. perfringens are similar in that both express a pore-forming toxin (listeriolysin O [LLO] and PFO, respectively) as well as phospholipase C. L. monocytogenes produces two different phospholipase C enzymes, which are reported to have partially overlapping roles in allowing L. monocytogenes to escape the primary phagosome and the double-membrane-bound compartment, which is part of the process of spreading from cell to cell (31). The cytotoxicity associated with PFO but lacking in LLO has been attributed to the pH activity profile of each toxin, where LLO is active mainly under acidic conditions but PFO is active over a broad range of pH values (13, 14). These activity-pH profiles have led to the proposal that LLO is active in the phagosomal compartment, which becomes acidified soon after being formed, but is relatively inactive in the neutral pH of the cytoplasm (13, 14). PFO, in contrast, is cytotoxic whether the toxin is secreted into a phagosome or the cytoplasm. L. monocytogenes is thought to be located much of the time in the intracellular compartment of the host cytoplasm, and so it would be important for Listeria to refrain from being overly cytotoxic to its host cell, which seems to be the case (10, 13, 14). C. perfringens is usually considered to be in an extracellular environment in the host, based on the lack of phagocytic cells in the vicinity of the infection in established cases of gangrene (7, 35, 36). However, if the MOI relative to macrophages is lower, C. perfringens does not appear to be very cytotoxic. This concept was verified by the experimental results shown in Fig. 5B and C, where an MOI of 1:1 showed low cytotoxicity to peritoneal macrophages but an MOI of 10:1 was cytotoxic after 5 h of incubation. It's possible to envisage a situation in which a single C. perfringens cell is phagocytosed by a macrophage under aerobic conditions, escapes the phagosome, and persists in the cytoplasm of the cell for a few hours. In contrast, L. monocytogenes can grow and multiply in the cytoplasm of macrophages for longer periods of time than we have proposed for C. perfringens (17).

The results we have presented in this report indicate C. perfringens cells can survive in the presence of macrophages, are cytotoxic to macrophages, and can escape the phagosome of macrophages if they are phagocytosed. Together, these results allow us to present the hypothesis that C. perfringens encounters phagocytic cells early in the infection process in humans, is able to resist phagocyte-mediated killing and, if the tissues are ischemic, can grow and develop into a clinical case of gangrene. To provide in vivo evidence to support the hypothesis, we set up experimental conditions in the mouse gangrene model to try to simulate the early stages of an infection seen in humans. We have assumed that while a large inoculum (108 to 109) is needed to cause gangrene in mice, a much smaller inoculum is needed in humans. The levels of C. perfringens found in soil and other potential sources of wound contamination (32) are consistent with this concept. Experimentally, this was done by inoculating mice with wild-type and mutant C. perfringens strains at a dose (106) 100- to 1,000-fold less than that needed to initiate a gangrene infection. Rather than looking for the onset of gangrene, we measured how long the bacteria could persist in the mouse muscle tissue. We observed that 24 h after inoculation, both the pfoA and plc mutant strains were recovered at levels that, on average, were ∼3 logs less than that seen with the wild-type strain (Fig. 7). The plc pfoA mutant strain was even more defective in its ability to survive in the mouse muscle tissue (Fig. 7D). In contrast, when the same strains were injected into mouse hind leg muscles at an inoculum of 109 cells, strains lacking PFO were able to initiate a gangrene infection while the strains lacking PLC were defective in this regard. These results suggest PFO plays a more significant role in the disease process when the relative numbers of bacteria, in relation to phagocytic cells, are low. One explanation may be the previously demonstrated role of PFO in cytotoxicity to PMNs (37-39) and the role we have demonstrated for PFO in mediating resistance to macrophage-mediated killing, since phagocyte-mediated killing is probably the immune function most responsible for clearing C. perfringens from infected tissues. However, our evidence that C. perfringens PFO actually performs this role in vivo is speculative; current experiments in our laboratory are investigating this issue.

In contrast to PFO, PLC was necessary for both the initiation of gangrene symptoms at high doses of bacteria and the persistence of C. perfringens in mouse muscle tissue (Fig. 7). Although PLC appears to have little cytotoxic effect on macrophages, a variety of other functions that are important in the initiation and spreading of a gangrene infection have been associated with this toxin. These include increased production of interleukin-8 and upregulation of cellular adhesion molecules on the surface of endothelial cells (8), increased blood clotting via the activation of gpIIbIIa on platelets (5, 6), and effects on the PMN oxidative burst response to antigens (38).

Modeling the early stages of a gangrene infection in humans by using sublethal doses of C. perfringens injected into mice has several weaknesses, the most obvious being that the mice do not develop gangrene, whereas humans do. While less than ideal, we think this alternative model may still provide clues to the development of the gangrene disease process. For example, as detailed above, the number of C. perfringens bacteria that contaminate human traumatic wounds is probably highly variable and based on a number of factors, but we suspect that it is significantly less than the 108 to 109 cells of strain 13 needed to cause gangrene in mice. Injecting lower numbers of bacteria into mice may be more indicative of the conditions seen in the early stages of human infections. Why mice are more resistant than humans to C. perfringens-dependent gangrene is not known, but one factor that may be important is that tissue ischemia is usually needed for clinical cases of gangrene to develop (34). The mouse inoculation model may not lead to development of ischemia at the site of infection when smaller doses of C. perfringens are injected, but the injection of large doses (108 to 109) may provide enough tissue damage and localized blood clotting to bring about ischemia at the site of injection and the subsequent development of a gangrene infection.

Surprisingly, we found that, after 24 h, ∼5% of the smaller inoculum (106) of wild-type bacteria was still viable in the mouse muscle tissue (Fig. 7A). In fact, surviving wild-type cells could be detected in mouse tissues up to 72 h postinfection with an inoculum of 106 bacteria (unpublished data). These results indicate vegetative C. perfringens cells can persist in host tissues for a significant period of time after inoculation into a wound area. This observation may be of clinical significance. Some cases of gangrene develop one to several days after trauma or surgery (34). The persistence of C. perfringens in the wound area may be an important factor in these delayed cases of posttraumatic or postsurgical gangrene infection. One possible scenario is that a traumatic wound becomes contaminated with C. perfringens cells but remains well vascularized and aerobic. C. perfringens may persist but not multiply in this environment. Subsequently, the blood supply to the area becomes compromised, perhaps by natural clotting factors or PLC-dependent functions (5, 6). The resulting hypoxia may permit the surviving C. perfringens cells to proliferate and initiate a clinically evident gangrene infection.

Acknowledgments

We thank Katherine Traughton (University of Tennessee—Memphis), Blair Therit, and John Varga for electron microscopy assistance; Bambi Jarrett, Michael Woodman, and Brandon Black for assistance with the in vivo mouse studies; A. Okabe for providing strain PLC-, Rodney Tweten for the gift of purified PFO, and A. L. Sonenshein, David Popham, and Donna Pate for critical reading of the manuscript.

Editor: V. J. DiRita

REFERENCES

- 1.Aderem, A., and D. M. Underhill. 1999. Mechanisms of phagocytosis in macrophages. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 17:593-623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Awad, M. M., A. E. Bryant, D. L. Stevens, and J. I. Rood. 1995. Virulence studies on chromosomal alpha-toxin and theta-toxin mutants constructed by allelic exchange provide genetic evidence for the essential role of alpha-toxin in Clostridium perfringens-mediated gas gangrene. Mol. Microbiol. 15:191-202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Awad, M. M., D. M. Ellemor, R. L. Boyd, J. J. Emmins, and J. I. Rood. 2001. Synergistic effects of alpha-toxin and perfringolysin O in Clostridium perfringens-mediated gas gangrene. Infect. Immun. 69:7904-7910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bryant, A. E., R. Bergstrom, G. A. Zimmerman, J. L. Salyer, H. R. Hill, R. K. Tweten, H. Sato, and D. L. Stevens. 1993. Clostridium perfringens invasiveness is enhanced by effects of theta toxin upon PMNL structure and function: the roles of leukocytotoxicity and expression of CD11/CD18 adherence glycoprotein. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 7:321-336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bryant, A. E., R. Y. Chen, Y. Nagata, Y. Wang, C. H. Lee, S. Finegold, P. H. Guth, and D. L. Stevens. 2000. Clostridial gas gangrene. I. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of microvascular dysfunction induced by exotoxins of Clostridium perfringens. J. Infect. Dis. 182:799-807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bryant, A. E., R. Y. Chen, Y. Nagata, Y. Wang, C. H. Lee, S. Finegold, P. H. Guth, and D. L. Stevens. 2000. Clostridial gas gangrene. II. Phospholipase C-induced activation of platelet gpIIbIIIa mediates vascular occlusion and myonecrosis in Clostridium perfringens gas gangrene. J. Infect. Dis. 182:808-815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bryant, A. E., and D. L. Stevens. 1997. The pathogenesis of gas gangrene, p. 185-196. In J. I. Rood et al. (ed.), The clostridia: molecular biology and pathogenesis. Academic Press, San Diego, Calif.

- 8.Bryant, A. E., and D. L. Stevens. 1996. Phospholipase C and perfringolysin O from Clostridium perfringens upregulate endothelial cell-leukocyte adherence molecule 1 and intercellular leukocyte adherence molecule 1 expression and induce interleukin-8 synthesis in cultured human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Infect. Immun. 64:358-362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Collie, R. E., and B. A. McClane. 1998. Evidence that the enterotoxin gene can be episomal in Clostridium perfringens isolates associated with non-food-borne human gastrointestinal diseases. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:30-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Decatur, A. L., and D. A. Portnoy. 2000. A PEST-like sequence in listeriolysin O essential for Listeria monocytogenes pathogenicity. Science 290:992-995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ellemor, D. M., R. N. Baird, M. M. Awad, R. L. Boyd, J. I. Rood, and J. J. Emmins. 1999. Use of genetically manipulated strains of Clostridium perfringens reveals that both alpha-toxin and theta-toxin are required for vascular leukostasis to occur in experimental gas gangrene. Infect. Immun. 67:4902-4907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Finlay, B. B., and S. Falkow. 1997. Common themes in microbial pathogenicity revisited. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 61:136-169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Glomski, I. J., A. L. Decatur, and D. A. Portnoy. 2003. Listeria monocytogenes mutants that fail to compartmentalize listeriolysin O activity are cytotoxic, avirulent, and unable to evade host extracellular defenses. Infect. Immun. 71:6754-6765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Glomski, I. J., M. M. Gedde, A. W. Tsang, J. A. Swanson, and D. A. Portnoy. 2002. The Listeria monocytogenes hemolysin has an acidic pH optimum to compartmentalize activity and prevent damage to infected host cells. J. Cell Biol. 156:1029-1038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heuck, A. P., R. K. Tweten, and A. E. Johnson. 2001. Beta-barrel pore-forming toxins: intriguing dimorphic proteins. Biochemistry 40:9065-9073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hogenauer, C., H. F. Hammer, G. J. Krejs, and E. C. Reisinger. 1998. Mechanisms and management of antibiotic-associated diarrhea. Clin. Infect. Dis. 27:702-710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jones, S., and D. A. Portnoy. 1994. Characterization of Listeria monocytogenes pathogenesis in a strain expressing perfringolysin O in place of listeriolysin O. Infect. Immun. 62:5608-5613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kameyama, K., O. Matsushita, S. Katayama, J. Minami, M. Maeda, S. Nakamura, and A. Okabe. 1996. Analysis of the phospholipase C gene of Clostridium perfringens KZ1340 isolated from Antarctic soil. Microbiol. Immunol. 40:255-263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Klempner, M. S. 1984. Interactions of polymorphonuclear leukocytes with anaerobic bacteria. Rev. Infect. Dis. 6(Suppl. 1):S40-S44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mandell, G. L. 1974. Bactericidal activity of aerobic and anaerobic polymorphonuclear neutrophils. Infect. Immun. 9:337-341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Melville, S. B., R. Labbe, and A. L. Sonenshein. 1994. Expression from the Clostridium perfringens cpe promoter in C. perfringens and Bacillus subtilis. Infect. Immun. 62:5550-5558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miller, M. A., M. J. Skeen, and H. K. Ziegler. 1998. Long-lived protective immunity to Listeria is conferred by immunization with particulate or soluble listerial antigen preparations coadministered with IL-12. Cell. Immunol. 184:92-104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Murti, K. G., D. S. Davis, and G. R. Kitchingman. 1990. Localization of adenovirus-encoded DNA replication proteins in the nucleus by immunogold electron microscopy. J. Gen. Virol. 71:2847-2857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ninomiya, M., O. Matsushita, J. Minami, H. Sakamoto, M. Nakano, and A. Okabe. 1994. Role of alpha-toxin in Clostridium perfringens infection determined by using recombinants of C. perfringens and Bacillus subtilis. Infect. Immun. 62:5032-5039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O'Brien, D. K., and S. B. Melville. 2000. The anaerobic pathogen Clostridium perfringens can escape the phagosome of macrophages under aerobic conditions. Cell. Microbiol. 2:505-519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O'Brien, D. K., and S. B. Melville. 2003. Multiple effects on Clostridium perfringens binding, uptake and trafficking to lysosomes by inhibitors of macrophage phagocytosis receptors. Microbiology 149:1377-1386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Olofsson, A., H. Hebert, and M. Thelestam. 1993. The projection structure of perfringolysin O (Clostridium perfringens theta-toxin). FEBS Lett. 319:125-127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Portnoy, D. A., R. K. Tweten, M. Kehoe, and J. Bielecki. 1992. Capacity of listeriolysin O, streptolysin O, and perfringolysin O to mediate growth of Bacillus subtilis within mammalian cells. Infect. Immun. 60:2710-2717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rood, J. I., and S. T. Cole. 1991. Molecular genetics and pathogenesis of Clostridium perfringens. Microbiol. Rev. 55:621-648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 31.Smith, G. A., H. Marquis, S. Jones, N. C. Johnston, D. A. Portnoy, and H. Goldfine. 1995. The two distinct phospholipases C of Listeria monocytogenes have overlapping roles in escape from a vacuole and cell-to-cell spread. Infect. Immun. 63:4231-4237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith, L. D. S. 1975. The pathogenic anaerobic bacteria, 2nd ed., p. 115-176. C.C. Thomas, Springfield, Ill.

- 33.Spitznagel, J. K. 1984. Nonoxidative antimicrobial reactions of leukocytes. Contemp. Top. Immunobiol. 14:283-343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stevens, D. L. 1997. Necrotizing clostridial soft tissue infections, p. 141-152. In J. I. Rood et al. (ed.), The clostridia: molecular biology and pathogenesis. Academic Press, San Diego, Calif.

- 35.Stevens, D. L. 2000. The pathogenesis of clostridial myonecrosis. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 290:497-502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stevens, D. L., and A. E. Bryant. 2002. The role of clostridial toxins in the pathogenesis of gas gangrene. Clin. Infect. Dis. 35:S93-S100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stevens, D. L., and A. E. Bryant. 1993. Role of theta toxin, a sulfhydryl-activated cytolysin, in the pathogenesis of clostridial gas gangrene. Clin. Infect. Dis. 16(Suppl. 4):S195-S199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stevens, D. L., J. Mitten, and C. Henry. 1987. Effects of alpha and theta toxins from Clostridium perfringens on human polymorphonuclear leukocytes. J. Infect. Dis. 156:324-333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stevens, D. L., R. K. Tweten, M. M. Awad, J. I. Rood, and A. E. Bryant. 1997. Clostridial gas gangrene: evidence that alpha and theta toxins differentially modulate the immune response and induce acute tissue necrosis. J. Infect. Dis. 176:189-195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Titball, R. W. 1997. Clostridial phospholipases, p. 223-242. In J. I. Rood et al. (ed.), The Clostridia: molecular biology and pathogenesis. Academic Press, San Diego, Calif.

- 41.Tweten, R. K. 1997. The thiol-activated clostridial toxins, p. 211-221. In J. I. Rood et al. (ed.), The clostridia: molecular biology and pathogenesis. Academic Press, San Diego, Calif.

- 42.Tweten, R. K., M. W. Parker, and A. E. Johnson. 2001. The cholesterol-dependent cytolysins. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 257:15-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]