Abstract

After interaction with tracheal epithelial cells, Bordetella pertussis induces the secretion of interleukin-6. This secretion is dependent on the expression of adenylate cyclase-hemolysin by the bacterium but not on the expression of other characterized bacterial toxins or adhesins. This finding confirms the important role of adenylate cyclase-hemolysin in the pathogenicity of the bacterium.

Bordetella pertussis, a human pathogen and the causative agent of whooping cough, secretes several virulence factors, including adhesins such as filamentous hemagglutinin (FHA) and pertactin (PRN) and toxins such as tracheal cytotoxin, pertussis toxin (PT), and adenylate cyclase-hemolysin (AC-Hly), allowing it to multiply and colonize the human respiratory epithelium (for a review, see reference 28). The synthesis of all these virulence factors, except tracheal cytotoxin, is positively regulated by the Bordetella virulence genes (bvg) in response to specific environmental signals. Bacteria expressing all these virulence factors are called Bvg wild-type bacteria. Mutations at the bvg locus result in Bvg mutants (with no expression of adhesins and toxins) (5).

Interactions between bacteria and respiratory epithelial cells can modulate the host immune response through the secretion of proinflammatory cytokines (16) and induce respiratory inflammation as observed in the lungs of patients who died of whooping cough (25). Respiratory pathogens, such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, and Chlamydia pneumoniae, produce a variety of molecules (such as lipopolysaccharide [LPS], adhesin, and flagellum) that interact with epithelial cells and cause secretion of proinflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-6 (IL-6), IL-8, and tumor necrosis factor alpha (7, 9, 13-15, 17-19, 22, 27, 33-35). It was previously shown that infection of a human bronchial epithelial cell line, BEAS-2B, with B. pertussis upregulates mRNA expression of a number of proinflammatory cytokine-encoding genes (genes for IL-6 and IL-8, etc.) and induces IL-6 and IL-8 protein secretion in the supernatants of infected cells (3). However, the bacterial factors responsible for this effect were not identified. In this study, we examined the effect of B. pertussis as well as that of purified toxin or adhesin on secretion of IL-6 and IL-8 by a human tracheal epithelial (HTE) cell line.

HTE cells infected with Bvg wild-type B. pertussis secrete IL-6 and IL-8 cytokines.

Simian virus 40-immortalized HTE cells were cultured on a collagen gel (Collagen G; Poly Labo) as described previously (11). Briefly, HTE cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (GIBCO Laboratories) supplemented with 2% Ultroser G (GIBCO Laboratories), streptomycin (100 μg/ml), and ampicillin (100 μg/ml; Sigma). Confluent monolayers of HTE cells were grown in 24-well plates to obtain 2.5 × 105 cells per well in 0.5 ml the day of the infection. The experiments were performed using either the parental Bvg wild-type strain (BP338) (32) or the Bvg mutant (BP359) (31). Bacteria were grown on Bordet-Gengou (BG) blood agar at 36°C for 5 days. Isolated colonies were then replated onto BG medium and incubated for 24 h before each experiment. Finally, the day of the infection, the bacteria were resuspended in the complete medium without antibiotics to an optical density at 650 nm of 1.0. Except when indicated, the following infection scheme was used: 2.5 × 107 CFU in 0.5 ml was added to each cell well to reach a bacterium/cell ratio of 100:1 and incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 24 h under static conditions. The bacterial inoculum was evaluated by plating dilutions of the bacterial suspension onto BG blood agar and counting CFU after 3 days at 37°C. As a positive control, the cells were stimulated with IL-1β (20 ng/ml; Sigma) (9), and as a negative control, the cells were incubated with culture medium to detect the basal level of cytokines secreted into the culture supernatant. Each condition was tested in triplicate. Culture supernatants were collected after 24 h of interaction between HTE cells and bacteria, centrifuged at 15,900 × g for 30 min, frozen, and stored at −80°C until assayed for IL-6 and IL-8 content by using homemade enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (6, 26). Briefly, microtitration plates (96 wells; Maxisorp; Nunclon, Rockeville, Denmark) were coated with 100 μl of mouse monoclonal anti-human IL-6 or IL-8/well for 2 h at 37°C or overnight at 4°C. After washings and the protein-blocking step, cell supernatants from activated cell cultures in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium, tested at 1:10 in phosphate-buffered saline-Tween-bovine serum albumin, were added in duplicate. A 2-h incubation was carried out at 37°C. After washings, rabbit polyclonal anti-human IL-6 or IL-8 was added for 90 min at 37°C. After further washings, peroxidase-labeled goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin (Silenus-AMRAD Biotech, Victoria, Australia) was added. After incubation at 37°C for 1 h, plates were washed and enzymatic activity was revealed by the addition of ortho-phenylene-diamine substrate (Sigma). The reaction was stopped by the addition of 3 N HCl. Optical densities at 490 and 630 nm were measured with a microplate reader spectrophotometer (Dynex Technologies, Chantilly, France). Titration curves were determined with recombinant human IL-6 and IL-8, respectively.

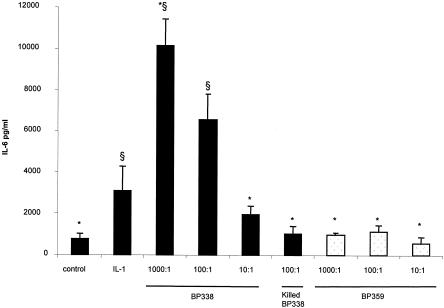

We first determined a dose response curve with different bacterium/cell ratios. As shown in Fig. 1, incubation of the parental strain BP338 with HTE cells led to a significant increase in levels of secreted IL-6 (P < 0.05) in supernatants of cell cultures compared to levels in supernatants of negative controls, and this increase was bacterial-dose dependent (Fig. 1). The ratio of 100 bacteria per cell was then chosen for all other experiments, as usually used (2, 10). Parental strain BP338 killed by heating at 56°C for 30 min did not stimulate cytokine production at a ratio of 100 bacteria per cell (Fig. 1) or at a ratio of 1,000 bacteria per cell (data not shown). Furthermore, the amount of IL-6 secreted was dependent on the expression of vir-activated genes since a Bvg mutant (BP359) was unable to induce IL-6 release even at a high bacterium/cell ratio (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

IL-6 secretion by HTE cells exposed to B. pertussis (live and heat-killed) parental Bvg wild-type (BP338) and Bvg mutant (BP359) bacteria for 24 h. Black columns represent BP338, and white columns represent BP359. Ratios of bacteria to cells were 1,000:1, 100:1, and 10:1 as indicated. IL-1β (20 ng/ml) was used as a positive control. The results are expressed in picograms of IL-6 per milliliter of culture fluid. Error bars represent the standard errors of the means of results from three to six experiments. One-way analysis of variance was used to identify differences between the groups. If the analysis of variance was significant, a nonparametric Mann-Whitney test was used to compare the means. A P value of <0.05 was considered significant. *, P of <0.05 versus BP338 (100 bacteria per cell). §, P of <0.05 versus negative control.

Parental strain BP338 also induced an increase in secreted IL-8 at a ratio of 100 bacteria per cell. However, this increase from 416 ± 50 pg/ml (mean ± standard error of the mean) to 711 ± 126 pg/ml (P = 0.03) was much smaller than the increase in secreted IL-6. Furthermore, in contrast to the secretion of IL-6, the secretion of IL-8 is not dependent on the expression of genes regulated by the bvg locus. In fact, the amount of IL-8 secreted by the Bvg mutant BP359 is not statistically different from the amount of IL-8 released by the parental Bvg wild-type strain BP338 (532 ± 164 versus 711 ± 126 pg/ml, respectively; P = 0.28).

Bacterial uptake is not involved in IL-6 secretion by HTE cells.

It was previously demonstrated that B. pertussis invades HTE cells (2). To determine whether this invasive capacity is necessary to induce IL-6 and IL-8 secretion by HTE cells, we measured cytokine production in the presence of cytochalasin D. An invasion assay was performed as described previously (2) with 24-h contact between HTE cells preincubated or not with cytochalasin D (5 μg/ml in 0.5% dimethyl sulfoxide) and parental strain BP338 (ratio of 100 bacteria per cell). The number of intracellular bacteria decreased from 0.5 ± 0.1 (mean ± standard error of the mean; three experiments) to 0.08 ± 0.02 bacteria per cell with cytochalasin D, confirming that this reagent blocks the internalization of more than 80% of B. pertussis bacteria by HTE cells.

The amounts of IL-6 produced by the cells after interaction with the bacteria were similar in the presence and absence of cytochalasin D (6,023 ± 2,022 and 6,346 ± 2,105 pg/ml, respectively). A similar observation was made for IL-8 (848 ± 261 and 711 ± 126 pg/ml, respectively). This result suggests that actin-mediated internalization of either whole organisms or ligands is not required to stimulate the epithelial IL-6 response. Similarly, the internalization of P. aeruginosa is not required to induce the secretion of IL-8 by the same cells used in this study (8).

AC-Hly is the bacterial factor involved in IL-6 secretion by HTE cells.

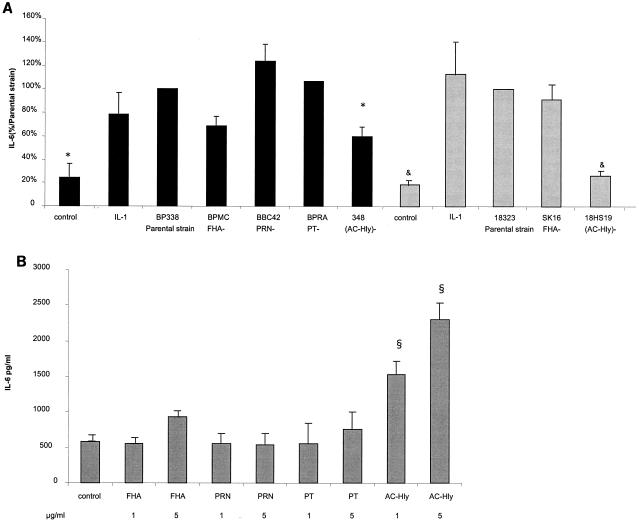

To characterize the bacterial factors involved in the secretion of IL-6 and IL-8 by the HTE cells, we first performed cytokine assays (as described above) with different mutants deficient in the expression of adhesins or toxins (at a ratio of 100 bacteria per cell). The strains and mutants used were the parental Bvg wild-type strains (BP338 and 18323) and their derived mutants: BPMC (FHA−) (24), BBC42 (PRN−) (29), BPRA (PT−) (1), BP348 (AC-Hly−) (32), SK16 (FHA−) (23), and 18HS19 (AC-Hly−) (20). The amounts of IL-6 secreted by the cells were not significantly different after interaction either with the parental strain BP338 or with its corresponding FHA-, PRN-, or PT-deficient mutants or with the parental strain 18323 or its corresponding FHA-deficient mutant (Fig. 2A).

FIG. 2.

IL-6 secretion by HTE cells exposed for 24 h to B. pertussis parental strains BP338 and 18323 and mutants (A) or to purified bacterial factors (B). (A) Black columns represent the BP338 background, and grey columns represent the 18323 background. Results shown are those from three to six experiments, except in the case of BPRA, for which experiments were done twice (realized in triplicate for each strain and mutant). The bacterium/cell ratio was 100:1. To combine data from different experiments, concentrations of IL-6 were normalized by setting the level of IL-6 secreted by HTE cells infected with the parental strain Bvg wild-type BP338 or 18323 24 h after infection at 100% within each experiment. One-way analysis of variance followed by a paired t test was used to identify differences between the groups. A P value of <0.05 was considered significant. P, <0.05 versus parental B. pertussis strain, BP338 Bvg wild type (*) or 18323 Bvg wild type (&). (B) The results are expressed in picograms of IL-6 per milliliter of culture fluid. ^, P of <0.05 versus negative control.

However, a significant difference was found with the mutants deficient in the expression of AC-Hly in either the BP338 or the 18323 background (P < 0.05) (Fig. 2A).

To confirm the results obtained with the different mutants, we examined the role of purified bacterial proteins. The infection scheme described above was carried out using purified FHA and PT (both a kind gift from M. J. Quentin-Millet of Aventis-Pasteur), PRN (a kind gift from P. Denoel of GlaxoSmithKline), and recombinant AC-Hly (4) incubated for 24 h at two concentrations (1 and 5 μg/ml). Recombinant AC-Hly was purified from Escherichia coli XL1 carrying the plasmid pCACT3 and analyzed as described earlier. Briefly, the toxin was purified after urea extraction, DEAE filtration, and affinity chromatography on calmodulin affigel (4). The data obtained with purified bacterial factors confirmed those obtained with the different mutants. In fact, purified PRN and PT did not elicit IL-6 secretion by the epithelial cells compared to the control (Fig. 2B). Purified FHA induced low amounts of IL-6 expression at 5 μg/ml (Fig. 2B) or at 25 μg/ml (data not shown) but with no statistical significance compared to the control. However, purified AC-Hly was able to trigger an IL-6 response after 24 h of incubation with the cells (Fig. 2B). In our study, we used recombinant AC-Hly produced and purified from E. coli. The purified enzyme was analyzed for purity by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. We tested the effect of preincubation of AC-Hly with polymyxin B (2 μg/ml) for 1 h at 37°C. The amounts of IL-6 induced by the cells stimulated by AC-Hly or by AC-Hly in the presence of polymyxin B were the same (data not shown), indicating that eventual E. coli LPS contamination does not play a role in the AC-Hly activation. Furthermore, the action of purified E. coli LPS was tested. No induction of IL-6 or IL-8 was observed after incubation of the cells with E. coli LPS at concentrations ranging from 1 to 10,000 ng/ml (data not shown). The action of AC-Hly on human epithelial cells seems to be specific. On the contrary, a recent study demonstrated that the expression of IL-6 by murine macrophages and dendritic cells is also enhanced by the action of AC-Hly but that this action synergizes with that of E. coli LPS (30).

Similar experiments were performed in order to determine the amounts of IL-8 secreted by the infected cells, but no significant differences were found whatever the mutant used (data not shown), confirming the results obtained with the Bvg mutant.

In conclusion, B. pertussis induces the synthesis of high levels of IL-6 but very low levels of IL-8 by human epithelial cells. The secretion of IL-6 is linked to the expression of AC-Hly. This finding confirms the important role of AC-Hly in the induction of the inflammatory response (12, 21).

Editor: J. D. Clements

REFERENCES

- 1.Antoine, R., and C. Locht. 1990. Roles of the disulfide bond and the carboxy-terminal region of the S1 subunit in the assembly and biosynthesis of pertussis toxin. Infect. Immun. 58:1518-1526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bassinet, L., P. Gueirard, B. Maitre, B. Housset, P. Gounon, and N. Guiso. 2000. Role of adhesins and toxins in invasion of human tracheal epithelial cells by Bordetella pertussis. Infect. Immun. 68:1934-1941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Belcher, C. E., J. Drenkow, B. Kehoe, T. R. Gingeras, N. McNamara, H. Lemjabbar, C. Basbaum, and D. A. Relman. 2000. The transcriptional responses of respiratory epithelial cells to Bordetella pertussis reveal host defensive and pathogen counter-defensive strategies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:13847-13852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Betsou, F., P. Sebo, and N. Guiso. 1993. CyaC-mediated activation is important not only for toxic but also for protective activities of Bordetella pertussis adenylate cyclase-hemolysin. Infect. Immun. 61:3583-3589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bock, A., and R. Gross. 2001. The BvgAS two-component system of Bordetella spp.: a versatile modulator of virulence gene expression. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 291:119-130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cavaillon, J. M., C. Marie, M. Caroff, A. Ledur, I. Godard, D. Poulain, C. Fitting, and N. Haeffner-Cavaillon. 1996. CD14/LPS receptor exhibits lectin-like properties. J. Endotoxin Res. 3:471-480. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clemans, D. L., R. J. Bauer, J. A. Hanson, M. V. Hobbs, J. W. S. Geme III, C. F. Marrs, and J. R. Gilsdorf. 2000. Induction of proinflammatory cytokines from human respiratory epithelial cells after stimulation by nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae. Infect. Immun. 68:4430-4440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DiMango, E., A. J. Ratner, R. Bryan, S. Tabibi, and A. Prince. 1998. Activation of NF-kappaB by adherent Pseudomonas aeruginosa in normal and cystic fibrosis respiratory epithelial cells. J. Clin. Investig. 101:2598-2605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DiMango, E., H. J. Zar, R. Bryan, and A. Prince. 1995. Diverse Pseudomonas aeruginosa gene products stimulate respiratory epithelial cells to produce interleukin-8. J. Clin. Investig. 96:2204-2210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ewanowich, C. A., A. R. Melton, A. A. Weiss, R. K. Sherburne, and M. S. Peppler. 1989. Invasion of HeLa 229 cells by virulent Bordetella pertussis. Infect. Immun. 57:2698-2704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gruenert, D. C., C. B. Basbaum, M. J. Welsh, M. Li, W. E. Finkbeiner, and J. A. Nadel. 1988. Characterization of human tracheal epithelial cells transformed by an origin-defective simian virus 40. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 85:5951-5955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guermonprez, P., N. Khelef, E. Blouin, P. Rieu, P. Ricciardi-Castagnoli, N. Guiso, D. Ladant, and C. Leclerc. 2001. The adenylate cyclase toxin of Bordetella pertussis binds to target cells via the alpha(M)beta(2) integrin (CD11b/CD18). J. Exp. Med. 193:1035-1044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hakansson, A., I. Carlstedt, J. Davies, A. K. Mossberg, H. Sabharwal, and C. Svanborg. 1996. Aspects on the interaction of Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae with human respiratory tract mucosa. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 154:S187-S191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Henderson, B., S. Poole, and M. Wilson. 1996. Bacterial modulins: a novel class of virulence factors which cause host tissue pathology by inducing cytokine synthesis. Microbiol. Rev. 60:316-341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jahn, H. U., M. Krull, F. N. Wuppermann, A. C. Klucken, S. Rosseau, J. Seybold, J. H. Hegemann, C. A. Jantos, and N. Suttorp. 2000. Infection and activation of airway epithelial cells by Chlamydia pneumoniae. J. Infect. Dis. 182:1678-1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kagnoff, M. F., and L. Eckmann. 1997. Epithelial cells as sensors for microbial infection. J. Clin. Investig. 100:6-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khair, O. A., R. J. Davies, and J. L. Devalia. 1996. Bacterial-induced release of inflammatory mediators by bronchial epithelial cells. Eur. Respir. J. 9:1913-1922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khair, O. A., J. L. Devalia, M. M. Abdelaziz, R. J. Sapsford, and R. J. Davies. 1995. Effect of erythromycin on Haemophilus influenzae endotoxin-induced release of IL-6, IL-8 and sICAM-1 by cultured human bronchial epithelial cells. Eur. Respir. J. 8:1451-1457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khair, O. A., J. L. Devalia, M. M. Abdelaziz, R. J. Sapsford, H. Tarraf, and R. J. Davies. 1994. Effect of Haemophilus influenzae endotoxin on the synthesis of IL-6, IL-8, TNF-alpha and expression of ICAM-1 in cultured human bronchial epithelial cells. Eur. Respir. J. 7:2109-2116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khelef, N., H. Sakamoto, and N. Guiso. 1992. Both adenylate cyclase and hemolytic activities are required by Bordetella pertussis to initiate infection. Microb. Pathog. 12:227-235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khelef, N., A. Zychlinsky, and N. Guiso. 1993. Bordetella pertussis induces apoptosis in macrophages: role of adenylate cyclase-hemolysin. Infect. Immun. 61:4064-4071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kube, D., U. Sontich, D. Fletcher, and P. B. Davis. 2001. Proinflammatory cytokine responses to Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection in human airway epithelial cell lines. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 280:493-502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee, C. K., A. L. Roberts, T. M. Finn, S. Knapp, and J. J. Mekalanos. 1990. A new assay for invasion of HeLa 229 cells by Bordetella pertussis: effects of inhibitors, phenotypic modulation, and genetic alterations. Infect. Immun. 58:2516-2522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Locht, C., M. C. Geoffroy, and G. Renauld. 1992. Common accessory genes for the Bordetella pertussis filamentous hemagglutinin and fimbriae share sequence similarities with the papC and papD gene families. EMBO J. 11:3175-3183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mallory, F. B., and A. A. Hornor. 1912. Pertussis: the histological lesion in the respiratory tract. J. Med. Res. 27:115-123. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marty, C., B. Misset, F. Tamion, C. Fitting, J. Carlet, and J. M. Cavaillon. 1994. Circulating interleukin-8 concentrations in patients with multiple organ failure of septic and nonseptic origin. Crit. Care Med. 22:673-679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Massion, P. P., I. Iromasa, J. Richman-Eisenstat, D. Grunberger, P. G. Jorens, B. Housset, J. F. Pittet, J. P. Wiener-Kronish, and J. A. Nadel. 1994. Novel Pseudomonas product stimulates interleukin-8 production in airway epithelial cells in vitro. J. Clin. Investig. 93:26-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mattoo, S., A. K. Foreman-Wykert, P. A. Cotter, and J. F. Miller. 2001. Mechanisms of Bordetella pathogenesis. Front. Biosci. 6:68-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roberts, M., N. F. Fairweather, E. Leininger, D. Pickard, E. L. Hewlett, A. Robinson, C. Hayward, G. Dougan, and I. G. Charles. 1991. Construction and characterization of Bordetella pertussis mutants lacking the vir-regulated P. 69 outer membrane protein. Mol. Microbiol. 5:1393-1404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ross, P. J., E. C. Lavelle, K. H. Mills, and A. P. Boyd. 2004. Adenylate cyclase toxin from Bordetella pertussis synergizes with lipopolysaccharide to promote innate interleukin-10 production and enhances the induction of Th2 and regulatory T cells. Infect. Immun. 72:1568-1579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weiss, A. A., and S. Falkow. 1984. Genetic analysis of phase change in Bordetella pertussis. Infect. Immun. 43:263-269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weiss, A. A., E. L. Hewlett, G. A. Myers, and S. Falkow. 1983. Tn5-induced mutations affecting virulence factors of Bordetella pertussis. Infect. Immun. 42:33-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wilson, M., R. Seymour, and B. Henderson. 1998. Bacterial perturbation of cytokine networks. Infect. Immun. 66:2401-2409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang, J., W. C. Hooper, D. J. Phillips, and D. F. Talkington. 2002. Regulation of proinflammatory cytokines in human lung epithelial cells infected with Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Infect. Immun. 70:3649-3655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang, J., W. C. Hooper, D. J. Phillips, M. L. Tondella, and D. F. Talkington. 2003. Induction of proinflammatory cytokines in human lung epithelial cells during Chlamydia pneumoniae infection. Infect. Immun. 71:614-620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]