Abstract

A new expression plasmid containing the fla operon promoter and a staphylococcal chloramphenicol resistance gene, was constructed to help assess the role of fliG in Treponema denticola motility. Deletion of fliG resulted in a nonmotile mutant with a markedly decreased number of flagellar filaments. Wild-type fliG genes from T. denticola and from Treponema pallidum were cloned into this expression plasmid. In both cases, the gene restored the ability of the mutant to gyrate its cell ends and enabled colony spreading in agarose. This shuttle plasmid enables high-level expression of genes in T. denticola and possesses an efficient selectable marker that provides a new tool for treponemal genetics.

Treponema denticola is an anaerobic, motile spirochete bacterium that is associated with periodontal disease (21, 29). T. denticola possesses four flagellar filaments, two of which are inserted at each end of the cell (2, 7). These complex filaments are composed of three FlaB core proteins and one FlaA sheath protein (26). Their unique periplasmic location allows the spirochete to locomote in high-viscosity environments, which is an important factor in pathogenesis (1, 12-14, 16, 27, 30).

Research on T. denticola has been hampered by a paucity of genetic tools and efficient selectable markers. An erythromycin resistance cassette has been used to generate a number of insertional mutants of T. denticola (15). More recently, a coumermycin-based shuttle plasmid was developed for complementation analysis (4). However, coumermycin-based selection suffers from a high background level of spontaneously resistant cells. Thus, there is a need to develop additional selectable markers for use in creating T. denticola shuttle plasmids that can be used for expression and complementation studies. Development of an efficient expression plasmid would enable the use of T. denticola as a surrogate system (3) to study homologous genes from Treponema pallidum, a pathogenic spirochete that is not cultivable in cell-free medium.

A motility-related operon in T. denticola is transcribed from a sigma 28-like promoter and encodes seven polypeptides that are homologous with components of the Salmonella flagellar basal body (FlgB, FlgC, FliE, FliF, and FliG), as well as three putative flagellar export proteins (FliH, FliI, and FliJ) (5, 6, 22-24). T. denticola FliG has a 31% amino acid sequence identity with Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium FliG, which is part of the flagellar switch complex (10, 22, 23, 32). In S. enterica serovar Typhimurium, FliG is involved in torque generation, directional rotation of the flagellar filament (8, 19, 20), and flagellar filament structure (8, 11). The role of fliG in T. denticola is unknown. Because the organization and regulation of spirochete motility genes are different from those of enteric bacteria, analysis of T. denticola fliG will enable us to gain a better understanding of the role of this protein in spirochete motility.

Strains and media.

T. denticola ATCC 33520 was grown at 36°C in New Oral Spirochete (NOS) broth with 10% rabbit serum or was plated on NOS medium containing 0.5% agarose (9, 18).

Construction and analysis of a fliG deletion mutant.

A suicide plasmid, pFEH1, was constructed (Fig. 1A) and was electroporated into T. denticola, using 5 to 10 μg of DNA as previously described (18). Plating was done on NOS-0.5% agarose plates containing 100-μg/ml erythromycin to select for double-crossover recombinants (18). After 1 week of incubation, small dense colonies grew on the surface of NOS-agarose plates. After growth in liquid medium, cells of this fliG deletion mutant, TDWΔFLIG, showed no movement when observed by dark-field microscopy.

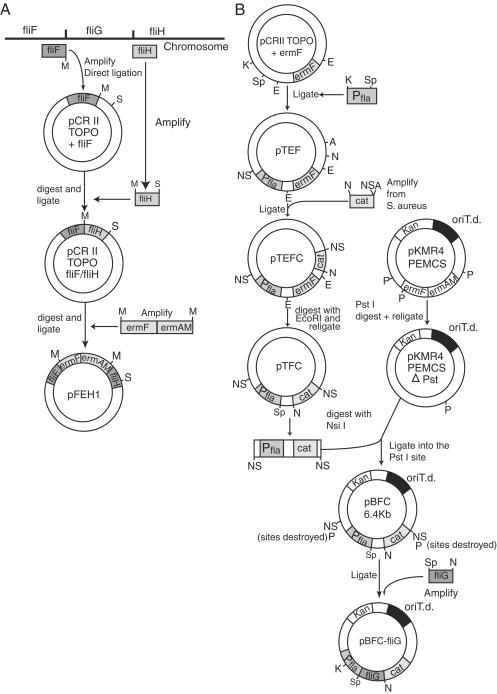

FIG. 1.

Plasmid constructions. (A) A suicide plasmid vector for generating a fliG deletion in T. denticola by allelic exchange. (B) A new expression plasmid, pBFC, that replicates and confers chloramphenicol resistance in T. denticola. This shuttle vector was used for cloning of T. denticola fliG as indicated for complementation analysis. NS, NsiI; P, PstI; M, MluI; K, KpnI; Sp, SpeI; S, SacI; N, NotI; A, ApaI; E, EcoRI; oriT.d., T. denticola origin of replication.

Electron microscopic analysis revealed that 39% of TDWΔFLIG cells did not possess any flagella, and 94% of cells for which both ends could be observed lacked a flagellar filament on at least one end. The flagellar filaments of TDWΔFLIG were usually shorter in length than those of the wild type. Cell ends lacking flagellar filaments also lacked hook and basal body structures. The phenotypic analysis of TDWΔFLIG is summarized in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Motility-related characteristics of wild-type T. denticola, TDWΔFLIG, and TDWΔFLIG harboring fliG on a newly constructed plasmid

| Strain | Avg no. of filaments/cell | Filament length (μm)a

|

Motility

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Median | Range | Gyration of cell ends | Agar spreading | ||

| 33520 (wild type) | 3.74 | 3.46 | 3.67 | 0.91-6.15 | Yes | Yes |

| TDWΔFLIG | 0.76 | 1.55 | 0.84 | 0.09-6.48 | No | No |

| TDWΔFLIG (pBFCFliG) | 1.03 | 3.36 | 3.08 | 0.88-10.46 | Yes | Yesb |

For T. denticola, n = 111; for TDWΔFLIG, n = 50; and for TDWΔFLIG(pBFCFliG), n = 72.

Colony diameter was less than that of the wild type.

Quantitation of RNA expression in TDWΔFLIG by RT-PCR.

RNA was isolated from logarithmic-phase T. denticola cells with the Masterpure Complete DNA and RNA purification kit (Epicentre Technologies, Madison, Wis.), with an additional DNase step employing a manganese buffer to eliminate residual DNA (31).

Primers specific for flgB, flgC, fliH, and fliI (Table 2) were designed with the Primer Express software (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.). For reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR), 90 ng of RNA was used in an RT-PCR according to the manufacturer's instructions (Applied Biosystems). T. denticola 16S rRNA was used as a reference target for quantitation (see Table 2 for primer sequences).

TABLE 2.

Oligonucleotide sequences used in this study for RT-PCR

| Primer | Sequence (5′→3′) | T. denticola gene target |

|---|---|---|

| FLGBRTF | GCAACGACTCATCCCTTGCAT | flgB |

| FLGBRTR | CCGTTTGCTTTTTCGGCAG | flgB |

| FIGCRTF | TTTATGATCCGGACCCATCCT | flgC |

| FIGCRTR | GGTTTGCCTCATAAGCCCTTG | flgC |

| fliG1349 | ACTGCCGTGCCTCCTAAAATG | fliG |

| fliG1449 | TTTGTAGCAGGAAGCTCGCCT | fliG |

| FliH424F | GTTTTAATCGCGGCGGTGA | fliH |

| FliH424R | TGGCGCCTATCCATTGCTTT | fliH |

| FLIIRTF | CCTCCCGAAGAATTTGATGAAG | fliI |

| FliIRTR | GCAAGTCAATTTCTGCCTGATG | fliI |

| 16SDENT1 | TGAGATACGGCCCAAACTCCT | 16S |

| 16SDENT2 | CAACCTTTCGGCCTTCTTCA | 16S |

| Flab160F | ACAATCGAAACAGCCGATGC | flaB1 |

| Flab172R | GACAACCGTCAACTCCATT | flaB1 |

| Flab257F | CGAAAAAGCTAACCGCGCT | flaB2 |

| Flab271R | GGAGGTTTTCTGCTGCGATA | flaB2 |

| Flab338F | AGGCCGTTTTGCTCAAGATT | flaB3 |

| Flab352R | TCCGCCTTGTTGTGCTCCTAT | flaB3 |

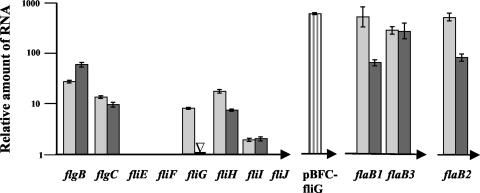

Quantitative RT-PCR of regions upstream (flgB and flgC) and downstream (fliH and fliI) of the ermF-ermAM cassette in the fliG deletion mutant showed expression levels similar to those of the wild type (Fig. 2). Since the presence of the erythromycin resistance cassette did not markedly affect transcription of downstream genes, these results demonstrate that this cassette does not contain transcription terminators or promoters that are functional in T. denticola.

FIG. 2.

Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of gene expression of wild-type T. denticola and TDWΔFLIG. The y-axis scale indicates the relative quantity of RNA, as compared to a 16S rRNA standard. The x axis indicates the genes comprising the noncontiguous operons, with the direction of transcription as indicated by the horizontal arrows. Light gray bars are the T. denticola wild type, dark gray bars are TDWΔFLIG, and the striped bar indicates the expression of fliG from TDWΔFLIG harboring the plasmid pBFCFliG. The open triangle represents where the erythromycin resistance cassette is inserted in TDWΔFLIG and indicates that no fliG RNA was detected. The error bars for each gene represent 1 standard deviation derived from at least two independent assays.

FlaB expression analysis.

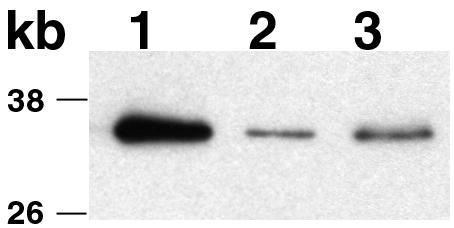

Immunoblots were incubated with a T. phagedenis FlaB antiserum (17) at a 1:3,000 dilution, followed by a peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (H+L) antibody (Pierce) at a 1:250,000 dilution. The FlaB polypeptides were visualized with the Pierce Super Signal West Dura kit. FlaB polypeptides were detectable in TDWΔFLIG, although at a markedly reduced level, compared to the wild type (Fig. 3). A similar reduction was noted in levels of the FlaA polypeptide (not shown).

FIG. 3.

Immunoblot with FlaB antiserum. The three FlaB polypeptides migrated as a single band under these gel running conditions. Lanes: 1, T. denticola wild type; 2, TDWΔFLIG; 3, TDWΔFLIG containing pBFCFliG. Note that the expression of flagellar filament polypeptides in TDWΔFLIG was only 17% that of the wild type.

Quantitative RT-PCR using primers specific for flaB1, flaB2, and flaB3 (Table 2) revealed that RNA levels in TDWΔFLIG were comparable to each other and to those in the wild type (Fig. 2). The regulatory mechanisms involved in the generation of a filament-deficient phenotype despite adequate levels of flaB RNA are unknown. Previously, we and others have qualitatively demonstrated a similar phenotype in other spirochete motility mutants (1, 18, 27). It is unclear whether the FlaB polypeptide is synthesized but rapidly degraded or whether it is not made at all, due to posttranscriptional regulation. In Borrelia burgdorferi, a decrease of FlaA in a FlaB mutant was shown to be a posttranscriptional effect (25).

Construction of a newly derived expression plasmid that confers chloramphenicol resistance in T. denticola.

The T. denticola replicative shuttle plasmid pKMR4PEMCS (3) was used as the basis for construction of a newly derived selectable plasmid (Fig. 1B). The new plasmid, pBFC, contained the T. denticola fla operon promoter (Pfla), located upstream of FliK/TapI (18), followed by the Staphylococcus aureus chloramphenicol resistance gene. The plasmid was electroporated into wild-type T. denticola and was selected on 10-μg/ml chloramphenicol.

The MIC of chloramphenicol for wild-type T. denticola is <1.0 μg/ml. T. denticola cells harboring pBFC grew well in 1.0 μg of chloramphenicol per ml, although they could grow in higher concentrations of this drug (up to 10 μg/ml). However, the growth rate slowed, and viability was reduced at the higher concentrations of chloramphenicol. For selection of transformants, 10 μg/ml was used in plated media to suppress background growth. The pBFC expression plasmid could be transformed and maintained in Escherichia coli, using kanamycin as a selectable marker, but it did not confer chloramphenicol resistance in E. coli.

The expression plasmid pBFC provides an important new tool for analysis of gene expression in T. denticola mutants. Use of chloramphenicol with this newly derived plasmid provides a method by which to obtain successfully transformed T. denticola cells with minimal or no background growth. It is likely, although not yet demonstrated, that this cat cassette will also be useful for generating chromosome-based gene interruptions.

Complementation analysis using fliG from T. denticola and T. pallidum.

T. denticola fliG was cloned into pBFC to form pBFCFliG (Fig. 1B). Quantitative RT-PCR demonstrated that the amount of fliG RNA expressed from this plasmid was greater than the amount of wild-type fliG RNA expressed from the chromosomal location (Fig. 2). The higher expression levels of fliG RNA are likely the result of the plasmid-borne location of the promoter (L. Slivienski-Gebhardt and R. Limberger, unpublished observations), but they do not adversely affect cell growth or morphology.

Flagellated cells of TDWΔFLIG harboring the plasmid pBFCFliG regained the ability to gyrate their cell ends in broth cultures, and the mean flagellar filament lengths were restored to the wild-type level. Cells also regained the ability to form spreading colonies on agarose plates, although colony diameters were less than wild type. The number of flagellar filament structures and the amount of FlaB polypeptides were slightly increased, although not to wild-type levels (Fig. 3 and Table 1). Conceivably, the synthesis and assembly of flagellar structures require expression of fliG at the lower wild-type levels, so as to ensure proper molecular stoichiometry. In B. burgdorferi, complementation of an flaB null mutant was achieved only after integration of flaB into the chromosome (28). Unfortunately, it is not yet technically feasible to insert fliG back into the T. denticola chromosome in order to attempt complementation from a chromosomal location.

T. pallidum fliG, cloned and expressed in pBFC, was also able to restore gyration of the cell ends of TDWΔFLIG, as well as colony spreading in agarose. This is the first report of a successful complementation of a T. denticola mutant by using a T. pallidum gene. T. pallidum FliG shows an 84% amino acid sequence identity with T. denticola and a 90% similarity. These experiments demonstrate the potential utility of T. denticola as a surrogate system in which to analyze the function of T. pallidum polypeptides.

Future development and application of additional genetic tools will be critical in resolving the mechanisms involved in the expression, regulation, and function of spirochete motility genes.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The entire sequence of fliG and partial sequences of fliF and fliH from T. denticola 33520 have been deposited in GenBank under accession no. AF343975.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Mary Beth Kinoshita, Dustin Vale-Cruz, and the Wadsworth Center Molecular Genetics and Electron Microscopy Core Facilities and Photography and Illustrations Unit for technical assistance. T. pallidum cells were kindly provided by K. Wicher (Wadsworth Center), and the FlaB antiserum was kindly provided by Nyles Charon, West Virginia University, Morgantown. Preliminary sequence data for T. denticola 35405 were obtained from The Institute for Genomic Research website (http://www.tigr.org) and the Baylor College of Medicine Human Genome Sequencing Center T. denticola sequencing project website (http://hgsc.bcm.tmc.edu/microbial/Tdenticola/), with support from NIH-NIDCR, and the Treponema Molecular Genetics website (http://dpalm.med.uth.tmc.edu/treponema/tpall.html).

This work was supported by Public Health Research Service grant AI34354 from the National Institutes of Health.

Editor: J. T. Barbieri

REFERENCES

- 1.Charon, N. W., and S. F. Goldstein. 2002. Genetics of motility and chemotaxis of a fascinating group of bacteria: the spirochetes. Annu. Rev. Genet. 36:47-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Charon, N. W., S. F. Goldstein, S. M. Block, K. Curci, J. D. Ruby, J. A. Kreiling, and R. J. Limberger. 1992. Morphology and dynamics of protruding spirochete periplasmic flagella. J. Bacteriol. 174:832-840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chi, B., S. Chauhan, and H. Kuramitsu. 1999. Development of a system for expressing heterologous genes in the oral spirochete Treponema denticola and its use in expression of the Treponema pallidum flaA gene. Infect. Immun. 67:3653-3656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chi, B., R. J. Limberger, and H. K. Kuramitsu. 2002. Complementation of a Treponema denticola flgE mutant with a novel coumermycin A1-resistant T. denticola shuttle vector system. Infect. Immun. 70:2233-2237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heinzerling, H. F., M. Olivares, and R. A. Burne. 1997. Genetic and transcriptional analysis of flgB flagellar operon constituents in the oral spirochete Treponema denticola and their heterologous expression in enteric bacteria. Infect. Immun. 65:2041-2051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heinzerling, H. F., J. E. Penders, and R. A. Burne. 1995. Identification of a fliG homologue in Treponema denticola. Gene 161:69-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holt, S. C. 1978. Anatomy and chemistry of spirochetes. Microbiol. Rev. 42:114-160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Irikura, V. M., M. Kihara, S. Yamaguchi, H. Sockett, and R. M. Macnab. 1993. Salmonella typhimurium fliG and fliN mutations causing defects in assembly, rotation, and switching of the flagellar motor. J. Bacteriol. 175:802-810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Izard, J., W. A. Samsonoff, M. B. Kinoshita, and R. J. Limberger. 1999. Genetic and structural analyses of the cytoplasmic filaments of wild-type Treponema phagedenis and a flagellar filament-deficient mutant. J. Bacteriol. 181:6739-6746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kihara, M., M. Homma, K. Kutsukake, and R. M. Macnab. 1989. Flagellar switch of Salmonella typhimurium: gene sequences and deduced protein sequences. J. Bacteriol. 171:3247-3257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kihara, M., G. U. Miller, and R. M. Macnab. 2000. Deletion analysis of the flagellar switch protein FliG of Salmonella. J. Bacteriol. 182:3022-3028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kimsey, R. B., and A. Spielman. 1990. Motility of Lyme disease spirochetes in fluids as viscous as the extracellular matrix. J. Infect. Dis. 162:1205-1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klitorinos, A., P. Noble, R. Siboo, and E. C. Chan. 1993. Viscosity-dependent locomotion of oral spirochetes. Oral Microbiol. Immunol. 8:242-244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li, C., A. Motaleb, M. Sal, S. F. Goldstein, and N. W. Charon. 2000. Spirochete periplasmic flagella and motility. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2:345-354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li, H., J. Ruby, N. Charon, and H. Kuramitsu. 1996. Gene inactivation in the oral spirochete Treponema denticola: construction of an flgE mutant. J. Bacteriol. 178:3664-3667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Limberger, R. J. 2004. The periplasmic flagellum of spirochetes. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 7:30-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Limberger, R. J., and N. W. Charon. 1986. Antiserum to the 33,000-dalton periplasmic-flagellum protein of “Treponema phagedenis” reacts with other treponemes and Spirochaeta aurantia. J. Bacteriol. 168:1030-1032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Limberger, R. J., L. L. Slivienski, J. Izard, and W. A. Samsonoff. 1999. Insertional inactivation of Treponema denticola tap1 results in a nonmotile mutant with elongated flagellar hooks. J. Bacteriol. 181:3743-3750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lloyd, S. A., H. Tang, X. Wang, S. Billings, and D. F. Blair. 1996. Torque generation in the flagellar motor of Escherichia coli: evidence of a direct role for FliG but not for FliM or FliN. J. Bacteriol. 178:223-231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lloyd, S. A., F. G. Whitby, D. F. Blair, and C. P. Hill. 1999. Structure of the C-terminal domain of FliG, a component of the rotor in the bacterial flagellar motor. Nature 400:472-475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Loesche, W. J. 1988. The role of spirochetes in periodontal disease. Adv. Dent. Res. 2:275-283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Macnab, R. M. 1992. Genetics and biogenesis of bacterial flagella. Annu. Rev. Genet. 26:131-158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Macnab, R. M. 2003. How bacteria assemble flagella. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 57:77-100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Minamino, T., R. Chu, S. Yamaguchi, and R. M. Macnab. 2000. Role of FliJ in flagellar protein export in Salmonella. J. Bacteriol. 182:4207-4215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Motaleb, M. A., M. Sal, and N. Charon. 2004. The decrease in FlaA observed in a flaB mutant of Borrelia burgdorferi occurs posttranscriptionally. J. Bacteriol. 186:3703-3711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ruby, J. D., H. Li, H. Kuramitsu, S. J. Norris, S. F. Goldstein, K. F. Buttle, and N. W. Charon. 1997. Relationship of Treponema denticola periplasmic flagella to irregular cell morphology. J. Bacteriol. 179:1628-1635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sadziene, A., D. D. Thomas, V. G. Bundoc, S. C. Holt, and A. G. Barbour. 1991. A flagella-less mutant of Borrelia burgdorferi: structural, molecular and in vitro functional characterization. J. Clin. Investig. 88:82-92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sartakova, M. L., E. Y. Dobrikova, M. A. Motaleb, H. P. Godfrey, N. W. Charon, and F. C. Cabello. 2001. Complementation of a nonmotile flaB mutant of Borrelia burgdorferi by chromosomal integration of a plasmid containing a wild-type flaB allele. J. Bacteriol. 183:6558-6564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Simonson, L. G., C. H. Goodman, J. J. Bial, and H. E. Morton. 1988. Quantitative relationship of Treponema denticola to severity of periodontal disease. Infect. Immun. 56:726-728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thomas, D. D., M. Navab, D. A. Haake, A. M. Fogelman, J. N. Miller, and M. A. Lovett. 1988. Treponema pallidum invades intracellular junctions of endothelial cell monolayers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 8:3608-3612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang, G., C. Barton, and F. G. Rodgers. 2002. Bacterial DNA decontamination for reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). J. Microbiol. Methods 51:119-121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yamaguchi, S., S.-I. Aizawa, M. Kihara, M. Isomura, C. J. Jones, and R. M. Macnab. 1986. Genetic evidence for a switching and energy-transducing complex in the flagellar motor of Salmonella typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 168:1172-1179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]