Abstract

Liposome vesicles could be formed at 65°C from the chloroform-soluble, total polar lipids (TPL) extracted from Mycobacterium bovis bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG). Mice immunized with ovalbumin (OVA) entrapped in TPL liposomes produced both anti-OVA antibody and cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses. Murine bone marrow-derived dendritic cells were activated to secrete interleukin-6 (IL-6), IL-12, and tumor necrosis factor upon exposure to antigen-free TPL liposomes. Three phosphoglycolipids and three phospholipids comprising 96% of TPL were identified as phosphatidylinositol dimannoside, palmitoyl-phosphatidylinositol dimannoside, dipalmitoyl-phosphatidylinositol dimannoside, phosphatidylinositol, phosphatidylethanolamine, and cardiolipin. The activation of dendritic cells by liposomes prepared from each purified lipid component of TPL was evaluated in vitro. A basal activity of phosphatidylinositol liposomes to activate proinflammatory cytokine production appeared to be attributable to the tuberculosteric fatty acyl 19:0 chain characteristic of mycobacterial glycerolipids, as similar lipids lacking tuberculosteric chains showed little activity. Phosphatidylinositol dimannoside was identified as the primary lipid that activated dendritic cells to produce amounts of proinflammatory cytokines several times higher than the basal level, indicating the importance of mannose residues. Although the activity of phosphatidylinositol dimannoside was little influenced by palmitoylation of mannose at C-6, a further palmitoylation at inositol C-3 diminished the induction levels of IL-6 and IL-12. Further, OVA entrapped in palmitoyl-phosphatidylinositol dimannoside liposomes was delivered to dendritic cells for major histocompatibility complex class I presentation more effectively than TPL OVA-liposomes. BCG liposomes containing mannose lipids caused up-regulation of costimulatory molecules and CD40. Thus, the inclusion of pure phosphatidylinositol mannosides of BCG in lipid vesicle vaccines represents a simple and efficient option for targeting antigen delivery and providing immune stimulation.

Heat-killed whole cells of Mycobacterium tuberculosis mixed with oil and an antigen result in strong adjuvant activity (11, 12). This combination, widely known as Freund's complete adjuvant (CFA), has been used in many laboratories to promote a strong antibody, as well as a strong cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL), response (26). However, CFA is toxic, causing acute inflammation, granulomas, and chronic toxicity (24), and is unacceptable, therefore, for human or veterinary use. It may be reasoned, however, that purified bioactive molecules from mycobacteria may prove useful as vaccine adjuvants without the associated toxicity issues.

The complex Mycobacterium spp. surface is composed of the cytoplasmic membrane surrounded by a cell wall made of mycoloyl arabinogalactan covalently attached to peptidoglycan and associated lipoarabinomannan (LAM). Lipids comprise part of these various outer layers and account for up to 60% by weight of the mycobacterial cell wall. This includes the mycolyl-arabinogalactan-peptidoglycan covalently linked polymer and several types of “extractable” lipids. Extractable lipids found in various strains include trehalose-containing glycolipids, glycopeptidolipids, phenolic glycolipids, lipooligosaccharides, phosphatidylinositol mannosides (PIMs), phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), and triacylglycerols (2, 32). PIMs with up to four fatty acyl chains were observed some time ago (4). A complete description of the structures from Mycobacterium bovis bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) of novel PIMs with palmitoyl and dipalmitoyl linkage sites identified at the inositol C-3 and mannose C-6 has been reported (21).

Active components identified in CFA include muramyl dipeptide and trehalose 6,6′-dimycolate from the cell wall (24). The phenolic glycolipid trehalose 6,6′-dimycolate (cord factor) is an active component in CFA, capable of promoting an antigen-specific CTL response (26) and moderate antibody titers when injected with an antigen in oil (12). Both the phenolic glycolipids and glycopeptidolipids have been shown to be on the cell surface and to be capable of down-regulating the immune system of the host during infection (22).

Biological effects of the chloroform-soluble phosphatidylinositol (PI) and PIMs from mycobacteria have been observed. Mycobacterial PI had the same ability as PIM2 (phosphatidylinositol dimannoside) with one to four acyl chains (all adsorbed to alum) to induce a granulomatous response and recruit natural killer T cells into the lesions, indicating no difference in biological response with the addition of mannose residues or additional acylation to PI (9). Liposomes have been constructed only by mixing cholesterol and other lipids with ethanolic extracts of BCG containing PI and PIMs (30). NO synthase activity was induced by these liposomes in macrophages but only subsequent to priming the macrophages with gamma interferon (IFN-γ) or trehalose dimycolate (30).

Herein, we prepare chloroform-soluble total polar lipids (TPL) by extracting BCG cells with chloroform-methanol-water (3) and characterize the recovered lipids as primarily PIM2, palmitoylated forms of PIM2, PI, PE, and cardiolipin. Novel liposomes are shown to form from these lipids (without mixing cholesterol or other lipids) uniquely at temperatures above 55°C with the properties of activating primary cultures of bone marrow-derived dendritic cells and augmenting antibody and cytotoxic T-cell responses to encapsulated antigen in vivo.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Commercial lipids.

Cholesterol, trehalose 6,6′-dimycolate, cardiolipin (bovine heart), l-α-dimyristoylphosphatidylcholine (DMPC), l-α-dimyristoylphosphatidylglycerol (DMPG), l-α-PI (soybean), l-α-phosphatidyl-l-serine (bovine brain), and l-α-dipalmitoylphosphatidylethanolamine (DPPE) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Oakville, Ontario, Canada).

Cultures.

M. bovis BCG was obtained from Robert North (Trudeau Institute, Saranac Lake, N.Y.) and grown aerobically at 37°C in shake flasks containing 7H9 medium supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) Middlebrook ADC enrichment (Becton Dickinson and Co.). EL-4 and EG.7, a subclone of EL-4 stably transfected with the ovalbumin (OVA) gene, were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection and maintained and grown as described previously (14).

Lipid extraction.

Total lipid extracts were obtained from fresh, washed cell paste of M. bovis by the Bligh and Dyer method (3). A one-phase solution of methanol, chloroform, and water (2:1:0.8, vol/vol) was added in a ratio of 15 g of cells (dry weight)/liter. The mixture was incubated at ambient temperature and stirred magnetically for 16 h and then centrifuged at 10,500 × g for 15 min. The pellet fraction was extracted twice more as above, and the supernatants were combined. A volume of chloroform and water each equal to the total volume of the chloroform-extractable lipids divided by 3.8 was added to obtain a two-phase system. The bottom chloroform phase containing the desired lipids was removed, and two 200-ml volumes of chloroform were used to wash the upper methanol-water phase. Polar lipids were recovered from the chloroform phases by flash evaporation to dryness, dissolving in small volumes of chloroform, and precipitation by the addition of 20 volumes of ice-cold acetone. The pellet obtained was washed twice with ice-cold acetone, dissolved in chloroform, and finally filtered through nylon 0.45-μm-pore-size filters to obtain chloroform-extractable TPL.

Lipid analysis.

Polar lipid extracts were analyzed by fast atom bombardment mass spectrometry (FAB-MS) with a JEOL JMS-AX 505H instrument operated at 3 kV in negative ion mode. The xenon gun was operated at 10 kV. Current-controlled full-scale scans were acquired at a rate of 10 s. A mixture of triethanolamine and Kryptofix (Sigma) was used as the matrix. Staining for functional groups was done after the polar lipids were separated on precoated 0.25-mm Silica Gel 60 thin-layer plates (Merck), developed with an acidic solvent of chloroform-methanol-acetic acid-water (85:22.5:10:4, vol/vol/vol/vol) or a basic solvent of chloroform-methanol-7 N ammonium hydroxide (60:35:8, vol/vol/vol). Lipid spots were characterized by using the phospholipid (Zinzade's reagent), glycolipid (α-naphthol), aminolipid (ninhydrin), and total lipid (sulfuric acid char reagent) sprays described previously (11). For sugar analysis lipids were first hydrolyzed with 2 M trifluoroacetic acid for 2 h at 100°C. d-Ribose was then added as an internal standard, and alditol acetate derivatives were prepared for identification and quantification by gas chromatography-MS (27). The total carbohydrate content of each lipid extract was determined by an anthrone reaction with d-glucose used as the standard.

Lipid purification.

To purify lipids by thin-layer chromatography, BCG TPL were applied as a band (6 mg) to 20- by 20-cm, 0.25-mm Silica Gel 60 glass plates (Merck). Plates were developed with chloroform-methanol-acetic acid-water (85:22.5:10:4, vol/vol/vol/vol). Iodine vapor detected the lipids that were subsequently recovered by Bligh and Dyer extraction of the adsorbent. Bands 3 and 4 sometimes merged and were recovered together. These lipids were separated and recovered by using a second plate developed with chloroform-methanol-7 N ammonium hydroxide (60:35:8, vol/vol/vol).

Phenol extraction.

LAMs were extracted with phenol from delipidated BCG as previously described (20).

Liposome preparation.

About 30 mg of TPL in chloroform was dried under a nitrogen stream, followed by 1 h under vacuum. Hydration was routinely done by adding 3 ml of pyrogen-free water, containing the antigen (10 mg of OVA), and incubating for 2 to 3 h at 65°C with shaking. To investigate the effect of temperature on liposome formation, hydration was allowed to occur at 35 to 75°C, in steps of 10°C. Average vesicle diameters were decreased between 80 and 100 nm in a sonic bath at 65°C. Preparations were then freeze-dried and rehydrated in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at 65°C. Liposomes were left overnight to anneal; then any OVA not associated with the liposomes was removed by ultracentrifugation, and the liposomes were washed three times with 8-ml volumes of PBS. The final liposome pellets were resuspended into PBS, and liposomes were filter sterilized with 0.45-μm-pore-size filters. The amount of entrapped OVA was quantified after lipid removal, and salt-free dry weights were determined. Average diameters were measured in a 5-mW HeNe laser particle sizer (model 370; Nicomp).

BCG liposomes were made from purified lipid fractions by the above method, except for BCG PE that was mixed with 80 mol% DMPC. Antigen-free liposomes were prepared from commercially available lipids as described for TPL of BCG, except a temperature of 35°C was used.

Immunizations.

Female C57BL/6 mice, 6 to 8 weeks of age, were immunized subcutaneously at the base of the tail with 0.1-ml volumes of immunogen at 0 and 21 days. Immunizations were with OVA (15 μg) either with no adjuvant (in PBS), entrapped in liposomes prepared from the TPL extracted from BCG, or mixed with Imject alum (Pierce) according to the manufacturer's instructions. In some cases, mice received 15 μg of OVA mixed with CFA in the first immunization and Freund's incomplete adjuvant in the second, each homogenized to 62% strength with PBS. Live recombinant M. bovis BCG expressing OVA257-264 (7) was injected once subcutaneously at a dose of 106 cells.

Analysis of humoral response.

Sera were collected from blood obtained from the tail veins of mice and analyzed for anti-OVA antibodies. The antibody titers were determined by indirect antigen-specific enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Briefly, ELISA plates (96-well flat-bottomed enzyme immunoassay microtitration plates; ICN Biomedicals Inc., Aurora, Ohio) were coated with antigen in PBS (10 μg/ml), and serial twofold dilutions of sera (from individual mice) were assayed in duplicate. Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG) plus IgM revealing antibody (Caltag, San Francisco, Calif.) was used to determine total antibody titers of sera. The reactions were developed with an ABTS [2,2′-azinobis(3-ethylbenzthiazolinesulfonic acid)] microwell peroxidase system (Kirkegaard and Perry Laboratories, Gaithersburg, Md.), and absorbance was determined at 415 nm after 15 min. Antibody titers are represented as endpoint dilutions exhibiting an optical density of 0.3 units above background.

CTL assays.

For CTL assays, 30 × 106 spleen cells were cultured with 5 × 105 irradiated (10,000 rads) EG.7 cells in 10 ml of R8 medium (8% fetal bovine serum) containing 0.1 ng of interleukin-2 (IL-2) per ml in 25-cm2 tissue culture flasks (Falcon), kept upright. After 5 days (at 37°C and 8% CO2), the cells recovered from the flask were used as effectors in a standard 51Cr release CTL assay, and the percent specific lysis against EG.7 (specific targets) and EL-4 (nonspecific targets) was determined (15).

ELISPOT assay.

The enumeration of IFN-γ-secreting cells was done by enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISPOT) assay (3, 31). Briefly, spleen cells were incubated in anti-IFN-γ antibody-coated ELISPOT plates in various numbers (in a final cell density of 5 × 105cells/well with spleen cells from naïve mice as feeder cells for low-cell-number conditions alone). IL-2 (1 ng/ml) and RPMI medium were included with and without OVA257-264 peptide (10 μg/ml) for a 48-h incubation at 37°C and 8% CO2. The plates were subsequently blocked and incubated with the biotinylated secondary anti-IFN-γ antibody (at 4°C overnight), followed by avidin-peroxidase conjugate (room temperature for 2 h). Spots were revealed by using diaminobenzidine.

Dendritic cell isolation and activation.

Bone marrow-derived dendritic cells were prepared as described previously (15) and were consistently >90% CD11c+ by flow cytometry on the day of harvest. Briefly, bone marrow was flushed from the femurs and tibias of C57BL/6 mice, and single-cell suspensions were made. Cells obtained were cultured (106 cells/ml) in RMPI medium supplemented with R8 medium and 5 ng of recombinant murine granulocyte macrophage colony stimulating factor (ID Labs, London, Ontario, Canada) per ml for 6 to 8 days at 37°C in 8% CO2. Nonadherent cells were removed at days 2 and 4 of culture, and fresh R8 medium plus granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor was added. Nonadherent dendritic cells were harvested on days 6 to 8. To test for activation and cytokine secretion, dendritic cells (105) were incubated in vitro with various concentrations of antigen-free liposomes or lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (from Escherichia coli; Sigma) in triplicate in 96-well tissue culture plates for 72 h at 37°C and 8% C02 in a humidified atmosphere. At 72 h, activation of the cells was assessed by measurement of dimethylthiazol diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT; Sigma-Aldrich) uptake. The supernatants were assayed for IL-12p40 and IL-6 by sandwich ELISA (19) by using antibody pairs purchased from BD Pharmingen (Mississauga, Ontario, Canada) and for tumor necrosis factor (TNF) by a bioassay using Wehi 164-13 cells (25).

Activation of dendritic cell costimulation.

Day 7 dendritic cells (3 × 105 to 5 × 105 cells/ml) were stimulated with 25 μg of the various antigen-free liposomes or LPS per ml in 24-well plates (Falcon). After 24 h at 37°C and 8% C02, cells were recovered, and 106 cells were stained with phycoerythrin-labeled fluorescent antibodies obtained from BD Pharmingen. Cell surface expression of CD80, CD86, CD40, CD11c, and major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I was assessed by flow cytometry (EPICS XL; Beckman Coulter). A total of 20,000 events were acquired for each sample, and data represent positive staining in the presence of specific fluorescent antibody.

In vitro antigen presentation.

Dendritic cells (105 cells/well) in 96-well microtiter plates were exposed to 10 μg of OVA entrapped in liposomes composed of BCG TPL or various lipids purified from TPL. Controls included untreated dendritic cells and dendritic cells with MHC class I loaded by incubation with 10 μg of OVA257-264 CTL epitope. After 4 h of incubation, the dendritic cells were washed and fixed and used to stimulate OT1 spleen cells (3 × 105 cells/well). The stimulation of OT1 cells (>90% of CD8+ OVA257-264 cells) was a measure of MHC class I presentation and was assessed by quantifying IFN-γ produced in the supernatant 24 h later. OT1 mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, Maine).

RESULTS

BCG liposomes.

The total lipids recovered by extraction with methanol-chloroform-water (2:1:0.8, vol/vol/vol) accounted for 10.2% ± 1% of the starting BCG cell dry weight, of which 65% was recovered as TPL and 35% as acetone-soluble lipids. TPL was dried from solvent, and liposome formation was monitored by phase-contrast microscopy after the addition of water or PBS buffer at temperatures ranging from 35 to 75°C. Liposomes did not form well below 55°C, resulting in clumps of lipid, but elevating the temperature to 65°C overcame this difficulty, especially when water rather than PBS was used for hydration. The average diameter of BCG liposomes was 230 ± 136 nm with OVA loadings in three preparations ranging from 33 to 67 μg/mg of liposomes (dry weight).

Immune response in mice.

As liposomes prepared from the chloroform-soluble lipids of BCG have not been tested as adjuvants in animals previously, we evaluated their potential to promote both humoral and CTL responses. TPL were used initially to ensure the inclusion of both immune active lipids and lipids that may direct antigen delivery to appropriate compartments of antigen-presenting cells.

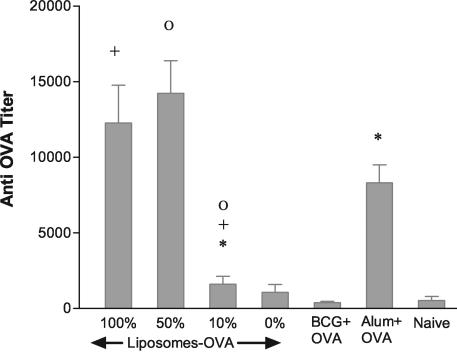

The humoral adjuvant activity of BCG-OVA liposomes was measured following subcutaneous immunizations at days 0 and 21. BCG liposomes served to promote an immune response to the entrapped antigen that was comparable to, but not significantly stronger than, immunizations with alum as an adjuvant (Fig. 1). Further, liposomes prepared from non-BCG lipids phosphatidylcholine (PC)-phosphatidylglycerol (PG)-cholesterol or with 10% of BCG TPL included were poor adjuvants. However, inclusion of 50% BCG lipids during liposome preparation from PC-PG-cholesterol resulted in a humoral adjuvant comparable to the 100% BCG liposome adjuvant. Furthermore, BCG liposomes admixed with soluble OVA prior to immunization were ineffective, indicating an essential carrier function in the delivery of antigen to mount a humoral immune response.

FIG. 1.

Ability of BCG TPL liposomes to have adjuvant effects on a humoral response in mice. C57BL/6 mice received subcutaneous injections at 0 and 21 days of 15 μg of OVA (naïve, or no adjuvant) or OVA admixed with alum or entrapped in liposomes. Liposomes were prepared from BCG TPL (100%) or diluted with commercial PC-PG-cholesterol (1.8:0.2:1.5, mol%) to achieve 50, 10, and 0% (wt/wt) of BCG lipids. BCG+OVA indicates mice injected with 15 μg of OVA admixed just prior to injections with an equivalent amount (0.5 mg) of antigen-free TPL liposomes. Anti-OVA antibody titrations were performed on blood samples taken on day 31. Similar data not shown were obtained for day 41. Data are the average ± standard error of the means of results for four mice per group (six mice per group for 100% BCG lipids). None of the means among 100% BCG-OVA, 50% BCG-OVA, or alum+OVA were statistically different (95% confidence) by an unpaired t test. Paired groups indicated by symbols (+, Ο, and *) were significantly different, with P values of 0.0097, 0.0013, and 0.0024, respectively.

For classical MHC class I presentation of antigen peptides to T cells, the antigen must be delivered to the cytosol of antigen-presenting cells. Although delivery is not achieved with liposomes consisting of PC-PG-cholesterol, liposomes composed of the lipids novel to Archaea are especially competent in this regard (16). To assess the possibility of class I presentation by BCG liposome adjuvants, we compared immunization with BCG-OVA liposomes to immunization with Freund's adjuvant admixed with OVA and to a live BCG recombinant expressing OVA257-264 peptide (Fig. 2). CTL assays of splenic cell effectors (Fig. 2A) show that activity with BCG liposomes as adjuvant was comparable to that with the live recombinant. For all adjuvants shown, effectors were specific to EG.7 targets expressing the OVA peptide as little killing (<4.6%) occurred for EL-4 targets. The frequency of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells in these spleens was tested by ELISPOT assay (Fig. 2B), determining the IFN-γ-secreting cells responding to OVA257-264 CTL epitope. Although whole splenic cell populations were tested, only CD8+ T cells respond to this MHC class I peptide (NK cell killing is not MHC restricted, and CD4+ T cells will not respond to this particular epitope). Results were essentially the same, in that live recombinant BCG-OVA and BCG-OVA liposomes demonstrated an ability similar to that of processed OVA to promote a specific immune response. Mice immunized with Freund's adjuvant in this assay evoked frequencies not significantly different (P > 0.5) from those with either BCG liposomes or live recombinant BCG cells.

FIG. 2.

Ability of BCG liposomes to have an adjuvant effect on the CD8+-T-cell response in mice. C57BL/6 mice received subcutaneous injections at 0 and 21 days of 15 μg of OVA homogenized in CFA followed by OVA in incomplete Freund's or of OVA entrapped in BCG TPL liposomes (BCG-OVA). Also shown are the results from a single injection of 106 live recombinant BCG cells expressing the main CTL epitope of OVA. Splenic cells were harvested 10 weeks after first injections for CTL and ELISPOT assays. CTL results are shown in panel A for various effector:target (E:T) cell ratios, where EL.4 cells represent nonspecific targets and EG.7 cells are specific targets expressing OVA257-264 peptide. IFN-γ-specific ELISPOT precursor frequencies are shown in panel B. ELISPOT frequencies (with peptide) for BCG-OVA, live BCG, and CFA+OVA are significantly different from results for the näive case (two-tailed t test, P values 0.0001, 0.0001, and 0.0303, respectively). The mean frequency of BCG-OVA compared to that of CFA+OVA (with peptide) was not significant (P value of 0.1306).

Because some variation in preparations may occur in the amounts of OVA entrapped per milligram of liposomes, we tested the possibility of variation in adjuvant activity over a broad range of loadings. Loading was typically 30 to 40 μg of OVA/mg of liposomes. The influence of antigen loading is insignificant for injections containing 15 μg of OVA encapsulated in from 0.22 to 1.8 mg (dry weight) of BCG liposomes (Fig. 3), indicating that there is no influence from the small variations in loading used in this study. This conclusion is supported by CTL assays and by the numbers of IFN-γ-secreting precursor CD8 T cells in spleens of the variously immunized mice.

FIG. 3.

Effect of antigen loading in BCG liposomes on induction of an immune response in mice. At 0 and 21 days C57BL/6 mice received subcutaneous injections consisting of 15 μg of OVA entrapped at various loadings in BCG TPL liposomes. Splenic cells from duplicate mice were harvested and pooled 6 weeks after the first injections for CTL and ELISPOT assays as described in the legend of Fig. 2. ELISPOT precursor frequencies are shown in panel B. Data are the means ± standard deviations of assays performed in triplicate.

Purification and characterization of BCG TPL lipids.

The lipids present in TPL were assigned based on the m/z signals obtained in negative-ion FAB-MS analysis (data not shown) as PI, PE, cardiolipin, and various PIMs. Dominant fatty acid carboxylate anions generated from the polar lipids during MS analysis are C16:0 (255.2 m/z), C19:0 (297.3 m/z), C18:0 (283.2 m/z), and C18:1 (281.3 m/z). The signal of m/z 297.3 corresponds to the M. tuberculosis C19:0 fatty acid 10-methyloctadecanoate, known as tuberculosteric acid (23). The presence of higher-molecular-weight lipids in TPL was excluded by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-MS analysis where the largest m/z signal observed corresponded to cardiolipin.

A chemical analysis of TPL revealed a carbohydrate content of 5.62% ± 0.79%, consisting primarily of mannose with detectable amounts of glucose. Arabinose, galactose, mannosamine, glucosamine, and galactosamine were absent or below detection. Inositol was found in 95% abundance relative to the mannose residues.

Thin-layer chromatography was used to separate TPL into six major lipid components, all of which stained positively for phosphate (Fig. 4). Fraction 3 had a similar mobility to soybean PI, and fraction 6 corresponded to a PE standard. Staining reactions (Table 1) further defined these six major lipids as phosphoglycolipids, phospholipids, and a phosphoaminolipid. The relative abundance and molecular anion signals for the purified lipids are shown in Table 1. Fraction 1 consisted of PIM2 with C19:0 and C16:0 chains. Lipid fraction 2 is primarily palm1-PIM2 (palm1 indicates pamitoylation at C-6 of mannose) with 9% PIM1, and fraction 3 is pure PI. In the case of PI, most molecules have C19:0 plus C16:0 chains, with the bulk of the remainder having C19:0 and C15:0 chains. Fraction 4 is a phosphoglycolipid defined by FAB-MS as palm2-PIM2 (palm2 indicates palmitoylation at both C-6 of mannose and C-3 of inositol). Palm1-PIM1 is a phosphoglycolipid of only 3% abundance in BCG TPL. Lipid 6 is pure PE with several fatty acyl chain combinations, primarily C18:0 plus C16:0 (C34:0). Phosphatidic acid fragment ions at m/z 647.1 and 675.1 confirm the PE assignments and correspond to fragments from C32:0 and C34:0, respectively. Finally, mobility on thin-layer plates, staining reaction, and FAB-MS identified fraction 7 as a cardiolipin with mainly C18:1 and C16:0 chains. Trehalose 6,6′-dimycolate standard ran just below the solvent front and was absent from TPL, as determined by thin-layer chromatography and MS (data not shown). The polar lipid structures found in TPL of M. bovis are shown in Fig. 5.

FIG. 4.

Thin-layer chromatogram showing the separation of BCG TPL into six major and one minor lipid fractions. Fractions are numbered 1 to 7, from most polar to least polar. Lipids (applied at the bottom of the plate) are BCG TPL and reference standards PI, l-α-phosphatidyl-l-serine, PG, and PE. An acidic solvent was used to develop the plate. Lipids were located by spraying with phosphate detection reagent.

TABLE 1.

Separation of the chloroform extractable TPL of BCG by thin-layer chromatography

| Lipida | Chainsb | Phosphate | Sugar | Amino | % of TPL (wt/wt)c | Major M− (m/z) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PIM2 | 35:0 | + | + | − | 8.6 | 1175.5 |

| palm1-PIM2 | 35:0 | + | + | − | 12.4 | 1413.6 |

| PI | 35:0 | + | − | − | 14.1 | 851.3 |

| palm2-PIM2 | 35:0 | + | + | − | 10.4 | 1651.4 |

| 38:0 | 1693.4 | |||||

| palm1-PIM1 | 35:0 | + | + | − | 3.0 | 1251.2 |

| PE | 32:0 | + | − | + | 25.9 | 690.1 |

| 34:0 | 718.1 | |||||

| 35:0 | 732.1 | |||||

| 37:0 | 760.1 | |||||

| CL | 34:1 | + | − | − | 24.4 | 1403.2 |

| 35:0 | 1419.1 |

CL, cardiolipin.

Observed dominant fatty acid carboxylate anions for PIM2 were 16:0/19:0, for palm2-PIM2 were 16:0/19:0 and 19:9/19:0, and for palm1-PIM1 were 16:0/19:0; dominant PEs were 16:0/16:0, 16:0/18:0, 16:0/19:0, and 18:0/19:0, and cardiolipins were 16:0/18:1 and 16:0/19:0.

Percentage abundance values are characteristic of three purifications from independent TPL extracts.

FIG. 5.

Structures of lipids PI, PIM2, palm1-PIM2, and palm2-PIM2 present in the TPL of BCG. Structural linkage details have been described previously (4, 21). The position sn-1 versus sn-2 of tuberculosteric acid may be reversed.

Activation of dendritic cells by liposomes.

To determine the potential adjuvant activity of BCG liposomes, we tested their ability to stimulate dendritic cells, as these represent the major antigen-presenting cells in mammals. Some variability in the absolute amounts of cytokine secretions is seen among the present studies, as each study represents separate dendritic cell isolations from bone marrow; however, the same trends in lipid activations were always observed. Two measures of dendritic cell activity were studied: overall activation by the MTT assay and inflammatory cytokine (IL-6, IL-12, and TNF) production. Bone marrow dendritic cells were cultured with 0 (R8 medium only) to 100 μg of liposomes (dry weight)/ml of R8 medium. After incubation the numbers of viable cells were quantified by the MTT assay, and inflammatory cytokines were assayed in the culture supernatants (Table 2). LAM extracted from BCG cells with phenol induced the secretion of IL-6, IL-12, and TNF by dendritic cells (Table 2), as predicted for cellular LAM (20). Immune response-stimulating activity was found also in liposomes prepared from the chloroform-extracted TPL, and this was retained even upon the removal of the neutral lipids. Cytokine secretions by dendritic cells declined when liposomes composed of BCG TPL were diluted with PC-PG-cholesterol.

TABLE 2.

Dendritic cells are activated by liposomes prepared from the TPL fraction of BCG

| Lipida | Cytokine production by liposome concn in culture medium

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL-6 (ng/ml)

|

IL-12 (ng/ml)

|

TNF (pg/ml)

|

||||

| 10 μg/ml | 100 μg/ml | 10 μg/ml | 100 μg/ml | 10 μg/ml | 100 μg/ml | |

| LAM | 78.0 ± 24 | 175 ± 78 | 186 ± 47 | >200 | 14.7 ± 5.7 | 38 ± 4.0 |

| TLE | 4.3 ± 4.2 | 35.2 ± 11 | 10.1 ± 4.8 | 96.0 ± 37 | 0.67 ± 0.58 | 2.7 ± 2.3 |

| TPL | 9.4 ± 2.5 | 44.3 ± 7.2 | 35.9 ± 1.9 | 128.3 ± 7.8 | 0.67 ± 1.2 | 2.5 ± 3.5 |

| 50% TPL | 1.9 ± 3.4 | 6.6 ± 11.4 | 2.1 ± 1.2 | 26.4 ± 12 | <0.1 | <0.1 |

| 10% TPL | 0.65 ± 1.1 | 0.17 ± 0.30 | 2.4 ± 0.48 | 19.3 ± 14 | <0.1 | <0.1 |

LAM was extracted from BCG cells with phenol. TPL liposomes from BCG are total lipid extracts with neutral lipids removed and were diluted 1:1 or 9:1 with DMPC-DMPG-cholesterol (1.8:0.2:1.5) to form 10 and 50% TPL liposomes. Data are the means ± standard deviations of triplicate cultures. TLE, liposomes prepared from total lipid extract.

We then compared the ability of antigen-free liposomes composed of purified BCG lipids PI and palm1-PIM2 to activate and induce TNF secretion from dendritic cells (Fig. 6). E. coli LPS was included for reference, as were liposomes composed of the TPL of BCG. In general, BCG TPL and purified component liposomes evoked similar MTT signals by dendritic cells. Strikingly, palm1-PIM2 liposomes were the most potent in inducing cytokine secretion even at low doses, indicating a predominant role for mannose and/or palmitoylated-mannose residues in the induction of proinflammatory TNF secretion.

FIG. 6.

Activation of bone marrow dendritic cells by BCG liposomes composed of palm1-PIM2 and PI. The average diameters of antigen-free liposomes were 93 ± 41 nm for TPL, 160 ± 95 nm for palm1-PIM2, and 162 ± 84 nm for PI. LPS from E. coli is shown as a positive control for activation. Sensitivity of the TNF bioassay was <0.1 pg/ml; values below the detection limit are graphed as zero. These experiments were repeated three times with the same results. O.D., optical density.

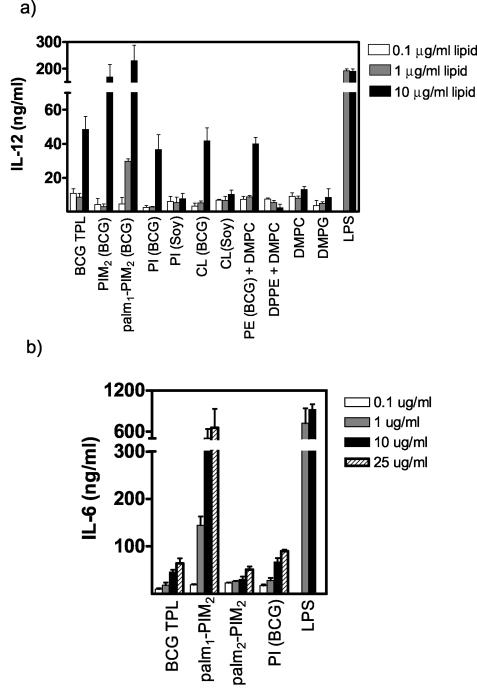

Liposomes consisting of BCG lipids including PI, PE, and cardiolipin (10 μg/ml) induced IL-12 secretion to comparable extents (Fig. 7a). Strikingly, PIM2 and palm1-PIM2 liposomes evoked IL-12 production that was several times higher than basal levels. As all liposomes containing tuberculosteric acyl chains had some ability to activate secretion of IL-12, a role for the tuberculosteric acid chain is implied for at least low-level immune response-stimulating potential. The striking level of activity above this basal activation obtained with PIM2 and palm1-PIM2, however, indicates an additional influence of the mannose moieties in the lipid head group. Liposomes composed of non-BCG lipids lacking tuberculosteric acid or other long acyl chain forms, namely, DMPC, DMPG, PI from soybean, DPPE plus DMPC, and cardiolipin from brain, were without significant activity, measured as IL-12 secretion from dendritic cells. Although palmitoylation of mannose carbon-6 had little influence on activity, the further addition of a palmitoyl chain at inositol carbon-3 resulted in liposomes with a considerably decreased ability to induce dendritic cells to secrete IL-12 (data not shown) and IL-6 (Fig. 7b), probably by head group conformational changes affecting receptor interactions.

FIG. 7.

IL-12 and IL-6 secretions from bone marrow dendritic cells induced by liposomes composed of BCG lipids compared to secretions induced by liposomes prepared from commercial lipids. Commercial lipids were PI and cardiolipin (CL) from soybean (soy), DMPC, DPPE, and DMPG. Liposomes and LPS were added to bone marrow dendritic cell cultures at the indicated concentrations of dry weight per milliliter and incubated 72 h before assay. Panels a and b represent separate experiments performed with different primary cultures of dendritic cells. These experiments were repeated three times with the same results.

Up-regulation of cell surface molecules.

The ability of antigen-free liposomes to up-regulate the expression of the costimulatory protein CD80 in dendritic cells was compared to that of TPL and purified lipids (Fig. 8). CD80 was expressed at low levels endogenously, but expression was up-regulated reasonably by all liposomes containing PIMs. PI from soybean was ineffective, and PI from BCG was only marginally active. CD86 and CD40, both expressed endogenously in these dendritic cells at larger amounts (33.1 and 25.3%, respectively) than CD80, showed similar, although less striking, up-regulation trends (data not shown). Constitutive expression of CD11c and MHC class I remained unchanged with the various treatments.

FIG. 8.

Up-regulation of costimulatory molecule CD80 on bone marrow dendritic cells exposed to antigen-free BCG liposomes. Dendritic cells were stimulated with 25 μg of the various liposomes or LPS per ml for 24 h, and cell surface expression of CD80 was assessed by flow cytometry. The circular gates indicate the percentages of CD80+ cells.

In vitro antigen presentation.

Because palm1-PIM2 was identified as a strong activator of dendritic cells (Fig. 6 and 7), we wanted to assess further its potential as a CTL adjuvant. The ability of BCG TPL and purified PI-based polar lipid liposomes to deliver encapsulated OVA to the MHC class I presentation pathway was assessed in bone marrow dendritic cells (Table 3). The efficiency of OVA delivery to the cytosol for processing was measured as IFN-γ production by OT1 CD8+ T cells specific for the MHC class I-OVA257-264 complex. A striking presentation of antigen occurred with palm1-PIM2 liposomes, even approaching that achieved by direct surface loading by OVA257-264 peptide. TPL and palm2-PIM2 liposomes delivered OVA, albeit less effectively for MHC class I processing, whereas PI liposomes were ineffective delivery vehicles.

TABLE 3.

MHC class I presentation of OVA-liposomes in bone marrow dendritic cellsa

| Antigen delivery | MHC class I presentation (IFN-γ, ng/ml)b

|

|

|---|---|---|

| 24 h | 48 h | |

| None | −0.83 ± 0.11 AB | −0.47 ± 0.09 A |

| BCG TPL | 2.50 ± 2.21 AC | 2.17 ± 3.16 B |

| palm1-PIM2 (BCG) | 17.2 ± 9.24 B | 24.6 ± 15.57 AB |

| palm2-PIM2 (BCG) | 1.53 ± 3.54 | 2.84 ± 4.04 |

| PI (BCG) | −0.34 ± 0.25 C | 1.39 ± 1.77 |

| OVA257-264 | 23.4 ± 2.04 | 32.4 ± 0.92 |

Dendritic cells were exposed to 10 μg of OVA entrapped in liposomes composed of either BCG TPL or purified BCG lipids. Data are the means ± standard deviations of triplicate cultures.

For each time point, paired groups significantly different (P < 0.5) from either the control (None) or BCG TPL values are marked with the same letter. OVA257-264 differs significantly from all groups with the exception of palm1-PIM2 (BCG).

DISCUSSION

Mycobacterial cells have long been documented as activators of the immune system when mixed with an antigen and oil, serving as the active ingredient of Freund's complete adjuvant (8). Although activity has been ascribed to lipid components including trehalose dimycolate (3), to our knowledge liposomes composed of mycobacterial glycerol membrane lipids have not been tested as antigen delivery systems. We now report that such liposomes prepared from chloroform-extractable polar lipids from the human vaccine strain of M. bovis BCG provide an antigen delivery system with immune modulatory activity. Lipid vesicles, however, did not form at 37°C. To form liposomes in aqueous media, phospholipids must be above their gel-to-liquid crystalline phase transition (18). By elevating temperatures above 55°C, it was possible to hydrate pure BCG lipids containing C19:0 fatty acyl chains and to observe spontaneous formation of liposomes from both TPL and purified lipid components. Because temperatures above 55°C are required to prepare liposomes efficiently from BCG TPL, or its purified components, it follows that at lower temperatures, such as body temperatures, the liposome membranes would pass from liquid crystalline phase to gel phase. These properties are a consequence of the presence of a 10-methyl, carbon-19 fatty acyl chain known as mycobacterial tuberculosteric acid (17, 23). Saturation of the fatty acyl chains is predicted to contribute to liposome stability. Indeed, the only BCG lipid in TPL that has unsaturation is the cardiolipin with chain combinations of 18:1, 16:0, and 19:0 (Table 1). These liposomes are in contrast to the leaky BCG liposomes prepared previously, requiring added cholesterol for retention of small molecules (1).

Several of the liposomes prepared from purified BCG lipids had immune stimulatory activity, shown by the activation (based on MTT uptake) of dendritic cells, the most potent cell type for processing and presenting antigen to T cells. These included the BCG phosphatidyl-myo-inositol anchor lipid (PI) and cardiolipin with long fatty acyl chains, and contrasted with PI from soybean or cardiolipin from brain that exhibited little activating capacity (data not shown). Similarly BCG liposomes composed of TPL, PI, cardiolipin, or PE promoted production of the inflammatory cytokine IL-12, suggesting a role for 10-methyloctadecyl fatty acyl chains. Other liposome types, such as PI (soybean), cardiolipin (brain), DPPE, DMPC, and DMPG, demonstrated little ability to activate dendritic cells either to take up MTT or to produce IL-12.

Although active lipids included BCG PI, where a glycerol backbone is linked at sn-1,2 with saturated fatty acyl C19:0 chains of tuberculosteric and C16:0 palmitic acids (23), cytokines IL-6 and IL-12, which are several times more inflammatory, were induced by PIM2 and palm1-PIM2 liposomes. These structures include the addition of two mannose residues linked at positions 2 and 6 of inositol, palmitoylated on C-6 of the mannosyl residue linked to the C-2 of inositol (21). TNF production was also induced best by palm1-PIM2 liposomes with detectably less activity for BCG PI liposomes and little to no activity for other BCG lipid liposomes tested or commercial ester lipid liposomes. However, the fact that PI from soybean (with no tuberculosteric acid chains) was inactive, whereas BCG PI showed some activity, points solidly to the tuberculosteric acid (C19:0) as a key structural difference that may provide low-level immune response-stimulating potential.

Interestingly, Campos et al. (5) have shown by using macrophages from Toll-like receptor 2 knockout mice that glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchors from the protozoan parasite Trypanosma cruzi are essential for induction of IL-12, TNF-α, and NO. This mode of action, still untested, may provide the mechanism whereby BCG liposomes containing PIM lipids activate dendritic cells to produce proinflammatory cytokines.

PE lipids are known generally for their capability to promote the fusion of membranes at acidic pH (6), such as may be encountered in the phagolysosome, and account for about 25% of the lipids in BCG TPL (Table 1). To mount a CTL immune reaction, it is first necessary to deliver antigen to the cytosol of antigen-presenting cells for processing. It follows that inclusion of this lipid in a liposome with antigen entrapped may aid in directing the antigen to MHC class I presentation, perhaps by acidic pH-dependent fusion events, consequently facilitating a CTL response to the encapsulated cargo (29). Indeed, adjuvant activity in mice included not only the MHC class II-mediated antibody arm of the immune response but also the MHC class I responses measured in terms of CTL and the frequency of antigen-specific IFN-γ-secreting CD8+ T cells. However, a strikingly enhanced presentation of antigen MHC class I peptide occurred in dendritic cells where the delivery liposome was palm1-PIM2 rather than BCG TPL (Table 3), clearly demonstrating the cytosolic delivery of encapsulated protein even in the absence of PE.

There have been no previous reports to our knowledge demonstrating either stable liposome construction from the polar chloroform-extractable lipids of mycobacteria without inclusion of other diluting lipids (30) or reports of immune modulation in dendritic cells by such liposomes. PIMs extracted from BCG have been mixed with cholesterol (2:1, wt/wt) or PE-cholesterol-oleic acid-PIM (7:5:3:1, wt/wt/wt/wt) to form liposomes with the ability to induce NO-synthase in thioglycolate-activated macrophages (30). Induction, however, first required the inclusion of IFN-γ as an activating signal or that macrophages be primed by trehalose dimycolate. Here, we have shown the activation of murine bone marrow-derived dendritic cells by liposomes composed of undiluted BCG lipids, requiring no additional activator.

In cases where the antigen and adjuvant are codelivered as a particulate system, efficiency may be expected to occur in the delivery of antigen to the same antigen-presenting cells activated by the adjuvant. Indeed, adjuvant activity required that antigen be associated with the liposomes of BCG, as little activity was noted when antigen and antigen-free liposomes were admixed prior to immunization (Fig. 1). Other adjuvant systems such as archaeosomes composed of the polar lipids from Archaea are especially suited as cell-mediated adjuvants and also promote antibody responses (13, 28). Archaeosomes are a self-adjuvanting delivery system, wherein archaeal lipid chains are similar to tuberculosteric acid to the extent of being fully saturated, long chains with methyl branching (10). While archaeosomes evoke inflammatory cytokine production by dendritic cells, the levels of activation are substantially lower than those of potent inflammatory ligands such as E. coli LPS (unpublished data). This is similar to our present study where BCG PI demonstrates moderate dendritic cell-activating potential, most likely attributable to the tuberculosteric acid chains. Taken together, an important role is implied for the PIM2 moiety in the activation of dendritic cells and cytokine production.

The present study is novel in preparing liposomes from pure chloroform-soluble TPL of BCG and the purified lipid components and in demonstrating that dendritic cells exposed to antigen-free PIM2 and palm1-PIM2 liposomes are activated to produce cytokines in the absence of other activators. Also, potential use of liposomes as vaccine adjuvants was demonstrated by the enhanced antibody and cytotoxic T-cell responses raised in animals to antigen entrapped in BCG liposomes. The efficient delivery of liposomes containing PIM may occur as these head groups may be recognized by the mannose receptor (1). While many studies have focused on the ability of phenol-extracted LAMs as immune stimulants, it is evident that active glycerolipid moieties are extractable with chloroform from BCG and may serve as potential adjuvants.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ken Chan for performing the FAB-MS analysis of lipids.

Editor: D. L. Burns

Footnotes

This study is publication no. 42491 of the National Research Council of Canada.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barratt, G., J. P. Tenu, A. Yapo, and J. F. Petit. 1986. Preparation and characterisation of liposomes containing mannosylated phospholipids capable of targetting drugs to macrophages. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 862:153-164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Besra, G. S., and P. J. Brennan. 1994. The glycolipids of mycobacteria, p. 203-232. In C. Fenselau (ed.), Mass spectrometry for the characterization of microorganisms. Oxford University Press, New York, N.Y.

- 3.Bligh, E. G., and W. J. Dyer. 1959. A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Can. J. Med. Sci. 37:911-917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brennan, P., and C. E. Ballou. 1967. Biosynthesis of mannophosphoinositides by Mycobacterium phlei. The family of dimannophosphoinositides. J. Biol. Chem. 242:3046-3056. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Campos, M. A., I. C. Almeida, O. Takeuchi, S. Akira, E. P. Valente, D. O. Procopio, L. R. Travassos, J. A. Smith, D. T. Golenbock, and R. T. Gazzinelli. 2001. Activation of Toll-like receptor-2 by glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchors from a protozoan parasite. J. Immunol. 167:416-423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Connor, J., M. B. Yatvin, and L. Huang. 1984. pH-sensitive liposomes: acid-induced liposome fusion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 81:1715-1718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dudani, R., Y. Chapdelaine, H. H. Faassen, D. K. Smith, H. Shen, L. Krishnan, and S. Sad. 2002. Multiple mechanisms compensate to enhance tumor-protective CD8(+) T cell response in the long-term despite poor CD8(+) T cell priming initially: comparison between an acute versus a chronic intracellular bacterium expressing a model antigen. J. Immunol. 168:5737-5745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Freund, J. 1956. The mode of action of immunologic adjuvants. Bibl. Tuberc. 5:130-148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gilleron, M., C. Ronet, M. Mempel, B. Monsarrat, G. Gachelin, and G. Puzo. 2001. Acylation state of the phosphatidylinositol mannosides from Mycobacterium bovis bacillus Calmette Guerin and ability to induce granuloma and recruit natural killer T cells. J. Biol. Chem. 276:34896-34904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kates, M. 1978. The phytanyl ether-linked polar lipids and isoprenoid neutral lipids of extremely halophilic bacteria. Prog. Chem. Fats Other Lipids 15:301-342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kates, M. 1986. Techniques of lipidology: isolation, analysis, and identification of lipids. Elsevier, New York, N.Y.

- 12.Koike, Y., Y. C. Yoo, M. Mitobe, T. Oka, K. Okuma, S. Tono-oka, and I. Azuma. 1998. Enhancing activity of mycobacterial cell-derived adjuvants on immunogenicity of recombinant human hepatitis B virus vaccine. Vaccine 16:1982-1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krishnan, L., C. J. Dicaire, G. B. Patel, and G. D. Sprott. 2000. Archaeosome vaccine adjuvants induce strong humoral, cell-mediated, and memory responses: comparison to conventional liposomes and alum. Infect. Immun. 68:54-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krishnan, L., S. Sad, G. B. Patel, and G. D. Sprott. 2000. Archaeosomes induce long-term CD8+ cytotoxic T cell response to entrapped soluble protein by the exogenous cytosolic pathway, in the absence of CD4+ T cell help. J. Immunol. 165:5177-5185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krishnan, L., S. Sad, G. B. Patel, and G. D. Sprott. 2001. The potent adjuvant activity of archaeosomes correlates to the recruitment and activation of macrophages and dendritic cells in vivo. J. Immunol. 166:1885-1893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krishnan, L., S. Sad, G. B. Patel, and G. D. Sprott. 2003. Archaeosomes induce enhanced cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses to entrapped soluble protein in the absence of interleukin 12 and protect against tumor challenge. Cancer Res. 63:2526-2534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leopold, K., and W. Fischer. 1993. Molecular analysis of the lipoglycans of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Anal. Biochem. 208:57-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lichtenberg, D., and Y. Barenholz. 1988. Liposomes: preparation, characterization, and preservation. Methods Biochem. Anal. 33:337-462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mosmann, T. R., and T. A. Fong. 1989. Specific assays for cytokine production by T cells. J. Immunol. Methods 116:151-158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nigou, J., M. Gilleron, B. Cahuzac, J. D. Bounery, M. Herold, M. Thurnher, and G. Puzo. 1997. The phosphatidyl-myo-inositol anchor of the lipoarabinomannans from Mycobacterium bovis bacillus Calmette Guerin. Heterogeneity, structure, and role in the regulation of cytokine secretion. J. Biol. Chem. 272:23094-23103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nigou, J., M. Gilleron, and G. Puzo. 1999. Lipoarabinomannans: characterization of the multiacylated forms of the phosphatidyl-myo-inositol anchor by NMR spectroscopy. Biochem. J. 337:453-460. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ortalo-Magne, A., A. Lemassu, M. A. Laneelle, F. Bardou, G. Silve, P. Gounon, G. Marchal, and M. Daffe. 1996. Identification of the surface-exposed lipids on the cell envelopes of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and other mycobacterial species. J. Bacteriol. 178:456-461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pangborn, M. C., and J. A. McKinney. 1966. Purification of serologically active phosphoinositides of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Lipid Res. 7:627-633. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Retzinger, G. S., S. C. Meredith, K. Takayama, R. L. Hunter, and F. J. Kezdy. 1981. The role of surface in the biological activities of trehalose 6,6′-dimycolate. Surface properties and development of a model system. J. Biol. Chem. 256:8208-8216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sad, S., R. Marcotte, and T. R. Mosmann. 1995. Cytokine-induced differentiation of precursor mouse CD8+ T cells into cytotoxic CD8+ T cells secreting Th1 or Th2 cytokines. Immunity 2:271-279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Skinner, M. A., R. Prestidge, S. Yuan, T. J. Strabala, and P. L. Tan. 2001. The ability of heat-killed Mycobacterium vaccae to stimulate a cytotoxic T-cell response to an unrelated protein is associated with a 65 kilodalton heat-shock protein. Immunology 102:225-233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sprott, G. D., J. Brisson, C. J. Dicaire, A. K. Pelletier, L. A. Deschatelets, L. Krishnan, and G. B. Patel. 1999. A structural comparison of the total polar lipids from the human archaea Methanobrevibacter smithii and Methanosphaera stadtmanae and its relevance to the adjuvant activities of their liposomes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1440:275-288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sprott, G. D., D. L. Tolson, and G. B. Patel. 1997. Archaeosomes as novel antigen delivery systems. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 154:17-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Straubinger, R. M., N. Duzgunes, and D. Papahadjopoulos. 1985. pH-sensitive liposomes mediate cytoplasmic delivery of encapsulated macromolecules. FEBS Lett. 179:148-154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tenu, J. P., D. Sekkai, A. Yapo, J. F. Petit, and G. Lemaire. 1995. Phosphatidylinositolmannoside-based liposomes induce NO synthase in primed mouse peritoneal macrophages. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 208:295-301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vijh, S., and E. G. Pamer. 1997. Immunodominant and subdominant CTL responses to Listeria monocytogenes infection. J. Immunol. 158:3366-3371. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang, L., R. A. Slayden, C. E. Barry III, and J. Liu. 2000. Cell wall structure of a mutant of Mycobacterium smegmatis defective in the biosynthesis of mycolic acids. J. Biol. Chem. 275:7224-7229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]