Abstract

From the invasive Citrobacter freundii strain 3009, an invasion determinant was cloned, sequenced, and expressed. Sequence analysis of the determinant showed high homology with the fim determinant from Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. The genes of the invasion determinant directed invasion of recombinant Escherichia coli K-12 strains into human epithelial cell lines of the bladder and gut as well as mannose-sensitive yeast agglutination and were termed fimCf genes. Expression of the FimCf proteins was shown by 35S labeling and/or Western blotting. In the infant rat model of experimental hematogenous meningitis, C. freundii strain 3009 and the in vitro invasive recombinant E. coli K-12 strain harboring the fimCf determinant reached the cerebrospinal fluid, in contrast to the case for the control strain. The fim determinant was also necessary for efficient in vitro invasion by C. freundii, because a deletion mutant was strongly reduced in its invasion efficiency. The mutation could be complemented in trans by the corresponding genes. Invasion by C. freundii could be blocked only by d-mannose, GlcNAc, and chitin hydrolysate and not by other carbohydrates tested. In contrast, yeast agglutination was not affected by GlcNAc or chitin hydrolysate. This finding indicated mannose residues to be essential for both yeast agglutination and invasion, whereas GlcNAc (oligomer) residues of host cells are involved exclusively in invasion. These results showed the fim determinant of C. freundii to be responsible for d-mannose- and GlcNAc-dependent in vitro invasion without being assembled into pili and for crossing of the blood-brain barrier in the infant rat model.

Citrobacter freundii strains are gram-negative, motile, rod-shaped bacteria of the family Enterobacteriaceae. They are widespread in nature and can be found in the environment in soil and water as well as in foodstuffs. C. freundii can be isolated from a wide variety of animals, such as household pets, birds, cattle, and fish. Although C. freundii is often considered a commensal of the human intestinal flora, this organism may cause urinary tract infections, diarrhea, gastritis, wound infections, and nosocomial infections such as pneumonia and, rarely, meningitis in newborns. Several probable virulence factors have been identified in C. freundii. Isolates from humans and beef samples were positive for the production of Shiga(-like) toxin II. This toxin is likely to be involved in enteropathogenicity caused by C. freundii. Furthermore, strains from patients with diarrhea produced a heat-stable enterotoxin identical to the 18-amino-acid Escherichia coli heat-stable enterotoxin STIa. Another probable virulence factor is a capsule, which is closely related to the Vi capsule of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi. Finally, the ability to invade several cell lines has been reported (22, 33).

Most invasive bacteria encode specific invasion systems. These invasion systems may be presented by a single surface protein such as the invasin of Yersinia enterocolitica or Yersinia pseudotuberculosis or the internalin A of Listeria monocytogenes. Other invasion systems are encoded by several genes and determine a type III secretion system and effector proteins injected into the host cell to be invaded. This kind of invasion system is employed by Salmonella and Shigella. In contrast, some invasive bacteria employ adhesins as invasins. Certain E. coli strains causing either intestinal or urinary tract infections harbor the afa-3 adhesin gene cluster. One of the afa-3 gene products, AfaD, is obviously not just an adhesin but also mediates invasion (23). Another nonfimbrial adhesin of pyelonephritis-associated E. coli is Dr-II which has been shown to direct internalization into HeLa cells (36). Related fimbrial adhesins inducing internalization are the Dr fimbriae of uropathogenic E. coli strains (16). Even certain variants of type 1 fimbriae are able to provoke bacterial invasion. These pili are the most widespread fimbrial adhesins among enterobacteria but vary in the amino acid sequence of the adhesive protein subunit FimH, located at the tip of the pilus (46). Some uropathogenic E. coli strains were reported to express type 1 pili which are not only essential for efficient infection of the urinary bladder but also responsible for the invasion of macrophages in the absence of opsonic antibodies and subsequent intracellular survival (2). Furthermore, these type 1 pili of uropathogenic E. coli are also able to induce bacterial internalization into urothelial cells of the bladder in a murine cystitis model (31).

Here, we report the molecular cloning, sequencing, and analysis of an invasion determinant from a urinary tract C. freundii isolate. This invasion determinant shows high homology to the type 1 pilus determinant of Salmonella, which, in contrast, does not mediate invasion.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, growth conditions, and plasmids.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Recombinant bacteria were cultivated with shaking at 37°C overnight in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth supplemented with the appropriate antibiotic (i.e., 30 μg of chloramphenicol per ml, 100 μg of ampicillin per ml, or 20 μg of kanamycin per ml). The antibiotics were purchased from Sigma (Deisenhofen, Germany). C. freundii strain 3009 (33) is from the strain collection of the Department of Bacterial Immunology, Walter Reed Institute of Research, Washington, D.C., and was grown in static nutrient broth at 37°C for 48 h. Before use in different experiments, C. freundii 3009 was usually passaged at least three times. M9 medium was supplemented with appropriate amino acids (0.1 mg/ml), 2 mM MgSO4, 100 μM CaCl2, 0.2% glucose, and 60 μM thiamine. Plasmid pTO3 was constructed by cloning partially digested (with Sau3A) chromosomal DNA of C. freundii 3009 into the BamHI site of cosmid vector pHC79. After transformation of noninvasive E. coli HB101, the resultant clones (3,840 clones) were screened for invasiveness in groups of 10 by performing the gentamicin protection assay (14). From the only group with a higher number of survivors than the average, each clone was tested for invasiveness individually. The only invasive clone was the one harboring cosmid pTO21052, which carries a ∼50-kb chromosomal insert. After digestion of cosmid pTO21052 with PvuII, plasmid pTO3 was obtained, which consists of a 10.9-kb chromosomal insert and the 2.7-kb BamHI/PvuII part of cloning vector pBR322 (22). Plasmid pPH1 was constructed by inserting the 9.6-kb EcoRI/SalI fragment of pTO3 into the EcoRI/SalI site of cloning vector pSU19. Ligating the 7.8-kb BamHI fragment of pTO3 to the pSU19 BamHI site resulted in a plasmid named pAA8. Plasmid pPH19 was constructed by cloning the 6.2-kb PstI fragment of pTO3 into the PstI site of cloning vector pBluescript II KS(+). By ligating the 9-kb EcoRI/XhoI insert of pTO3 to EcoRI- and SalI-digested pT7-3 and pT7-6, respectively, plasmids pB7-3 and pB7-6 were obtained. Plasmid pPH4 is a truncated derivate of pPH1 achieved by deletion of the HpaI/SnaI fragment, containing part of fimDCf and genes fimHCf to fimZCf, and subsequent religation. Suicide plasmid pPH13 was designed by ligating the 4-kb SalI/KpnI fragment from pPH4 into the multiple cloning site of suicide vector pJP5603 (35) which was digested with the same restriction enzymes. The deletion mutant C. freundii 3009-dz was obtained by transfer of the suicide plasmid pPH13 via conjugation from donor strain E. coli S17-1λpir to C. freundii strain 3009 and subsequent double crossover, which led to the exchange of the wild-type allele with the in vitro construct missing part of fimDCf and genes fimHCf to fimZCf. Plasmid pPH23 was constructed by inserting the 5.7-kb SmaI/SnaI fragment of pPH1 into the broad-host-range vector pK19mob (39) which was linearized with SmaI.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids

| Strain or plasmid | Characteristic(s) relevant for this study | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| C. freundii | ||

| 3009 | Human UTI isolate | 33 |

| 3009-dz | Δfim(D)HFZCf, 3009 derivate | This study |

| E. coli | ||

| AAEC189 | K-12, Δfim, afimbriated | 5 |

| BL21(DE3)pLysS | B, F−ompT hsdSB(rB− mB−) gal dcm (DE3)(pLysS)(Cmr) | 40 |

| DH5α | K-12, fim+, predominantly fimbriated | 21 |

| HB101 | K-12, fim+, not fimbriated | 10 |

| S. enterica serovar Typhimurium C17 | Clinical isolate | 30 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pBR322′ | 2.7-kb BamH1/PvuII part of pBR322, Apr | 7 |

| pJP5603 | Suicide vector, Kmr, oriR6K, mobRP4 | 35 |

| pK19mob | Broad-host-range vector, oriV oriT mobRP4, Kmr | 39 |

| pSU19 | Cloning vector, Cmr | 3 |

| pT7-3 | Expression vector, bla under φ10 promoter control, Apr | 41 |

| pT7-6 | Expression vector, bla not under φ10 promoter control, Apr | 41 |

| pAA8 | pSU19 carrying fimAICDHCf | This study |

| pANN801-13 | pBR322 carrying sfaI from E. coli strain 536, Apr | 20, 25 |

| pAZZ50 | pBR322 carrying sfaII from E. coli strain IHE3034, Apr | 18 |

| pB7-3 | fimAICDHFCf under φ10 promoter control in pT7-3 | This study |

| pB7-6 | fimAICDHFCf in pT7-6 antiparallel to the φ10 promoter | This study |

| pGB30 | pHC79 carrying fimEc from E. coli strain 536, Apr | 19 |

| pISF101 | pACYC184 carrying fimSt from S. enterica serovar Typhimurium, Cmr | 11 |

| pMMP658-6 | pBR322 carrying sfr from E. coli strain BK658, Apr | 34 |

| pPH1 | pSU19 carrying fimAICDHZCf | This study |

| pPH4 | Religated 7.1-kb HpaI/SnaI fragment of pPH1 | This study |

| pPH13 | 4-kb SalI/KpnI of pPH4 in suicide vector pJP5603 | This study |

| pPH19 | 6.2-kb PstI fragment of pTO3 in pBluescript II KS carrying fimICDHFCf | This study |

| pPH23 | pK19mob carrying fimDHFZCf | This study |

| pPH24 | pPH1 with IS1 in fimACf | This study |

| pPIL110-54 | pACYC184 carrying foc from E. coli strain AD110; Cmr | 24, 44 |

| pTO3 | pBR322 carrying the whole fim cluster from C. freundii | 22 |

DNA sequencing and sequence alignments.

Plasmid pTO3 was sequenced by the chain termination method (38), using a LI-COR DNA sequencer model 4000 (MWG-Biotech AG, Ebersberg, Germany). PCR was done with the Thermo Sequenase cycle sequencing kit (Amersham-Pharmacia, Freiburg, Germany) with primers complementary to the cloning vector pBR322 as well as forward and reverse primers designed from available DNA sequences (by primer walking). Sequence analysis was performed with the Genetics Computer Group and CLUSTALW programs and tools available at the website of the National Center for Biotechnology Information. Nucleotide and protein sequence homology searches were done by BLAST search (National Center for Biotechnology Information).

Cell lines, media, and culture conditions.

The human bladder epithelial cell line T24 was purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, Va.). RT112, a human urinary bladder carcinoma cell line, was kindly provided by T. F. Meyer, Max-Planck-Institut für Infektionsbiologie, Berlin, Germany (8). The T24 cell line was cultivated in McCoy's 5A medium supplemented with 2 mM glutamine, nonessential amino acids, and 10% fetal calf serum. RT112 cells were grown in Waymouth MB 752/1 medium with 10% fetal calf serum. Both cell lines were cultivated in medium without antibiotics at 37°C in a 5% CO2-95% air atmosphere with ∼90% humidity and were split twice a week at a ratio of 1:5 to 1:10. All cell culture media and supplements were purchased from Gibco (Gaithersburg, Md.), except for McCoy's 5A, which was from C.C. Pro (Neustadt, Germany).

Invasion assay.

For invasion assays, the human epithelial cells were seeded into 24-well plates (Falcon) and incubated in medium without antibiotics overnight at 37°C. Invasion assays were performed essentially as described by Elsinghorst (14). Briefly, a 5- to 50-μl volume of a bacterial overnight culture was added to 2 ml of fresh LB medium and incubated with shaking until it reached the early logarithmic growth phase (optical density at 600 nm of 0.4 to 0.6). Approximately 1 × 105 to 2 × 106 bacteria were added to a confluent monolayer of epithelial cells and incubated for up to 3 h at 37°C in a 5% CO2-95% air atmosphere (invasion period). The actual value for each inoculum was determined by a colony plate count. After the invasion period, the monolayer was washed twice with Earle's balanced salt solution, and fresh prewarmed medium containing 100 μg of gentamicin per ml was added to kill the extracellular bacteria. After another 1 h incubation the monolayer was washed three times with Earle's balanced salts solution and lysed with 0.2% sodium deoxycholate in distilled water for 4 min. The viability of all strains used in this study was not affected by the 0.2% sodium deoxycholate treatment. The released intracellular bacteria were enumerated by a quantitative plate count. Invasion ability was expressed as the percentage of the inoculum surviving the gentamicin treatment. Each assay was conducted in duplicate and was independently repeated at least three times. Results are expressed as the means from all replicate experiments. In control experiments, the gentamicin sensitivity of all strains included in this study was demonstrated in the absence of epithelial cells by using equivalent bacterial numbers and under the same conditions as in invasion assays. All bacteria were killed in those control studies after treatment with gentamicin (100 μg/ml) for 1 h. Epithelial cell viability and monolayer integrity were routinely monitored by addition of trypan blue (Hazleton Biologics, Lenexa, Kans.) and light microscopic analysis.

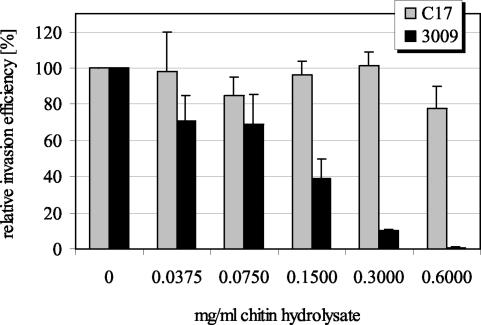

Invasion assays in the presence of carbohydrates.

All of the carbohydrates used were directly dissolved in the appropriate cell culture medium at 100 mM, except for chitin hydrolysate (0.6 mg/ml). Chitin hydrolysate is a mixture of N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) and oligomers of this carbohydrate (Vector Laboratories, Grünberg, Germany). In 24-well plates, the bacterial inoculum was added to 1 ml of cell culture medium with and without a particular carbohydrate and incubated with shaking at room temperature for 15 min. After removal of the tissue culture medium from the epithelial cell monolayer, the preincubated bacterial culture without and with carbohydrate was added to the monolayer and invasion assays were continued as described above. Carbohydrates were present during the invasion period. Inhibition of C. freundii 3009 internalization by chitin hydrolysate in a dose-dependent manner was analyzed at concentrations of 0.0375 to 0.6 mg/ml. Control studies under identical conditions but in the absence of human cells demonstrated that none of the carbohydrates used adversely affected bacterial viability. Trypan blue staining was performed to ensure human cell monolayer integrity under the assay conditions used.

Yeast cell agglutination.

Prior to use, bacteria were routinely examined for type 1 fimbriae expression by mannose-sensitive yeast cell agglutination on glass slides (37). Type 1 fimbriae expression of bacteria was confirmed by agglutination after addition of an equal volume of baker's yeast suspension in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to the bacterial culture in the presence or absence of 2% d-mannose.

ELISA-based assay.

In order to determine whether sfaI, sfaII, sfr, foc, and fim determinant-carrying recombinant bacteria and control strain HB101, harboring the plasmid vector pBR322, are fimbriated or not, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) were performed (25). Overnight bacterial cultures were centrifuged, and bacterial pellets were resuspended in a carbonate buffer (pH 9.5) to a concentration of 109 CFU/ml. Flat-bottom 96-well ELISA plates (CML-CEB, Nemours, France) were coated with bacteria (200 μl/well) and left overnight at 4°C. After removal of the unbound bacteria, the wells were blocked with 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA)-PBS (pH 7.4) for 2 h at 37°C and washed three times with PBS. Subsequently, 100 μl of serially diluted fimbriae-specific rabbit polyclonal antibody solutions in PBS-0.5% BSA were added to each well and incubated at 37°C for 90 min. After another washing step, horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (Dako, Hamburg, Germany) in PBS-1% BSA (1:2,000) was added and incubated for 1 h at 37°C (100 μl/well). Following a final wash, the bound enzyme was detected by the addition of substrate (100 μl/well; Pierce ImmunoPure TMB substrate kit) for 5 to 30 min. The reaction was stopped by adding 100 μl of 2 M H2SO4 per well. The A450 was measured with an ELISA reader.

Adherence assay.

Adherence was quantified by a modified invasion assay. For that assay, epithelial cells were seeded in wells of a 96-well plate and incubated for 24 h. To the confluent epithelial cell monolayer, 8 μl (i.e., ∼108 bacteria) of a static overnight culture of the strain of interest was added and incubated under cell culture conditions for 2 h. The number of epithelial cell-associated bacteria was determined by plate count. After five washing steps, cell-associated bacteria were resuspended in 0.2% Triton X-100 for 20 min, and 100-μl volumes of appropriate dilutions were plated.

Heat extraction of fimbrial proteins.

Type 1 fimbriae are heat extractable (26). For preparation of heat-extracted proteins, fimbriated bacteria were pelleted by centrifugation and suspended in 0.5 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4) containing 75 mM NaCl, followed by a 30-min incubation period at 60°C in a shaking water bath. After removal of bacteria by centrifugation, the crude fimbrial preparations were concentrated from the supernatant with a cellulose filter (Centricon YM-10; Millipore, Eschborn, Germany) by passing liquid and molecules smaller than 10 kDa through the filter.

Western blot analysis.

Heat-extracted proteins were separated by electrophoresis (32 mA, 60 min) on a sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-13% polyacrylamide gel (27) and were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane by electrophoretic blotting (43). The blocked membranes were probed with various rabbit antisera. Following incubation of goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (Dako), the membranes were developed by using an ECL kit (Amersham-Pharmacia) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Prestained full-range Rainbow marker (RPN 800; Amersham-Pharmacia) was used as a molecular weight standard. C. freundii-specific FimF and FimH polyclonal antisera were prepared by immunization of rabbits with synthesized peptides derived from FimF (LHDSDRTRLPLEQAS) and FimH (AGAGNRPEGINPQTK), respectively, conjugated to carrier molecule keyhole limpet hemocyanin (Eurogentec, Herstal, Belgium).

Autoradiography.

To radiolabel FimCf proteins, plasmids which carry a T7 promoter were used for specific fimCf gene expression with T7 RNA polymerase (41). Briefly, 30 μl of BL21(pLysS) (harboring various expression plasmids) overnight cultures was grown in 1 ml of LB medium supplemented with 1% glucose, 50 μg of ampicillin per ml, and 20 μg of chloramphenicol per ml, at 37°C with shaking, to an optical density at 600 nm of 0.5 to 0.7. The bacterial pellet was washed with LB medium and was resuspended in 1 ml of LB medium containing the above-mentioned antibiotics and 2 mM IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside). Following a 30-min incubation at 37°C with shaking, the bacteria were harvested, washed with M9 medium, and resolved in 1 ml of M9 medium without methionine and cysteine to be cultivated at 37°C for 1 h. Rifampin was added to a final concentration of 200 μg/ml, and after another 25-min incubation, the plasmid proteins were labeled with a mixture of [35S]methionine and [35S]cysteine (10 μCi) (Pro-Mix; Amersham-Pharmacia). Whole-cell extracts obtained from bacteria were separated by electrophoresis on an SDS-13% polyacrylamide gel (27). After electrophoresis, the gel was stabilized by incubation for 30 min in a solution of 10% acetic acid and 10% methanol, followed by another 30-min incubation in a solution consisting of 10% glycerol, 10% methanol, and 1 M salicylic acid (pH 7.2). A PhosphorImager, kindly provided by J. Köhrle, University of Würzburg, was used to visualize the radiolabeled proteins.

Transmission electron microscopy.

Bacteria from repeated subcultures in static liquid LB broth were resuspended in saline. The presence of type 1 pili and type 1 pilus-like adhesins on the surfaces of bacteria was detected by mannose-sensitive yeast agglutination. A 30-μl aliquot of the bacterial suspension was placed on top of a Formvar-coated copper grid and left for 1 min. After sedimentation, the bacteria were stained with a 30-μl drop of 2% uranyl acetate for 30 s. The grids were blotted dry and examined in a Zeiss 10A transmission electron microscope at 60 kV.

Neonatal rat model.

The ability of C. freundii 3009, recombinant E. coli HB101(pPH1), and control strain HB101(pSU19) to cross the blood-brain barrier was examined as described by Wang et al. (45). Briefly, outbred, specific-pathogen-free Sprague-Dawley rats with timed conception were purchased from Charles River Breeding Laboratories (Willington, Mass.). The rats delivered in our vivarium 5 to 7 days after they arrived. At 5 days of age, all members of each litter were randomly divided into three groups to receive via intracardiac injection 3.9 × 107, 8.2 × 108, and 5.4 × 108 CFU of C. freundii 3009, recombinant E. coli HB101(pPH1), and E. coli HB101(pSU19), respectively. Approximately 1 to 2 h after bacterial inoculation, blood and cerebrospinal fluid specimens were obtained for quantitative cultures.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence of the C. freundii fim gene cluster has been deposited in the GenBank database and given accession number AJ508060.

RESULTS

Cloning of an invasion determinant from C. freundii strain 3009.

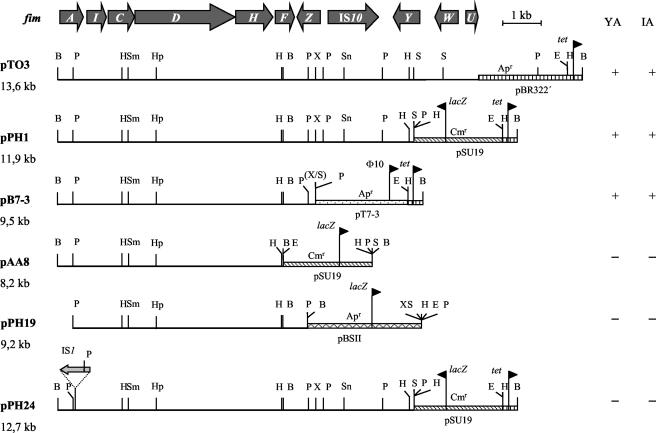

Recent studies revealed the ability of C. freundii strain 3009, a urinary tract isolate, to invade several human cell lines in vitro (33). To identify an invasion system in C. freundii strain 3009, cosmid cloning followed by screening for invasive clones was performed. To ensure cloning of large fragments of chromosomal C. freundii DNA partially digested with Sau3AI to the cosmid, cloning vector pHC79, previously linearized with BamHI, was chosen. Transformation of the noninvasive E. coli K-12 strain HB101 with the resulting recombinant cosmids was performed, and the transformants were screened for their ability to invade T24 human bladder epithelial cells. The invasion ability of recombinant clones was tested by employing the gentamicin protection assay. An invasive recombinant clone harboring cosmid pTO21502 with an insert of about 50 kb was identified. Digestion of pTO21052 with PvuII and religation resulted in plasmid pTO3 (13.6 kb) (Fig. 1). This plasmid had lost the cos site of the vector pHC79, contained an insert of 10.9 kb, and mediated invasion into T24 cells (Fig. 1). Furthermore, the pTO3-carrying strain also invaded other human bladder cells, as well as epithelial cells of the gut and even human brain microvascular endothelial cells (Table 2).

FIG. 1.

Physical maps of plasmids containing the complete (pTO3) or parts of the type 1 fimbrial gene cluster from C. freundii strain 3009. The genes fimA to fimF on the plasmids are sufficient to enable recombinant E. coli HB101 or AAEC189 to agglutinate yeast cells and invade human bladder epithelial (T24) cells. B, BamHI; E, EcoRI; H, HindIII; Hp, HpaI; P, PstI; S, SalI; Sm, SmaI; Sn, SnaI; X, XhoI; YA, d-mannose-sensitive yeast agglutination; IA, invasion ability; ▥, pBR322-derived DNA; ▧, pSU19-derived DNA; ░⃞, pT7-3-derived DNA;  , pBluescript II KS-derived DNA.

, pBluescript II KS-derived DNA.

TABLE 2.

In vitro invasion efficiencies for different cell lines by C. freundii, S. enterica serovar Typhimurium, and recombinant E. coli carrying various plasmids or vector controls

| Cell line | Human origin | % Invasiona |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

C. freundii |

S. enterica serovar Typhimurium C17 |

E. coli HB101 carrying: |

|||||||

| 3009 | 3009-dz | pTO3 | pPH1 | pB7-3 | pSU19 | pBR322 | |||

| T24 | Bladder | 11.4 ± 6.6 | 2.2 ± 1.9 | 52.1 ± 23.0 | 9.7 ± 6.8 | 6.1 ± 2.2 | 5.3 ± 2.6 | 0.05 ± 0.04 | 0.01 ± 0.01 |

| RT112 | Bladder | 27.3 ± 4.1 | 2.1 ± 0.8 | NDb | 9.9 ± 2.1 | ND | ND | 0.02 ± 0.01 | 0.03 ± 0.02 |

| HCT8 | Ileocecum | 67.2 ± 29.6 | ND | 41.4 ± 39.3 | 3.7 ± 1.7 | 1.0 ± 0.6 | 3.3 ± 1.4 | 0.05 ± 0.04 | 0.01 ± 0.03 |

| HBMECc | Brain | 3.3 ± 1.2 | ND | ND | ND | 2.6 ± 1.3 | ND | ND | 0.01 ± 0.01 |

Data are the means ± standard deviations from at least three independently performed invasion assays.

ND, not determined.

HBMEC, human brain microvascular endothelial cells.

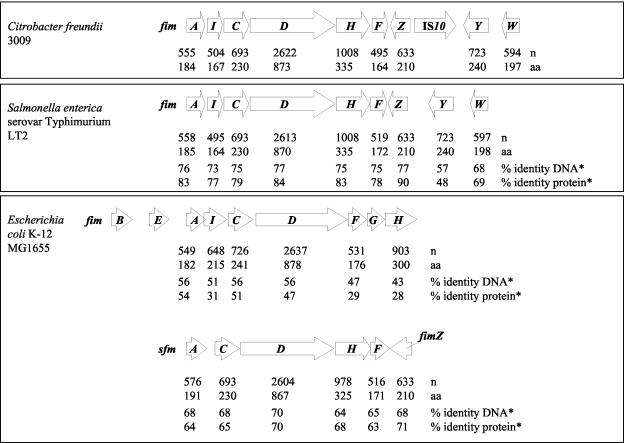

Sequence analysis of the invasion determinant of C. freundii 3009.

Sequencing of the insert of pTO3 revealed 11 open reading frames (Fig. 1). Of these, 10 were found to exhibit the highest rate of identity with the type 1 fimbrial gene cluster of S. enterica serovar Typhimurium (Fig. 2). In contrast to the fimbrial gene cluster of S. enterica serovar Typhimurium, an insertion sequence (IS) element identical to IS10 of E. coli was located between fimZ and fimY in C. freundii 3009. Except for the presence of IS10, the structure of the C. freundii invasion determinant was identical regarding number and arrangement to the S. enterica serovar Typhimurium fim genes (Fig. 2). In contrast, homology with the fim genes of E. coli K-12 was much lower. This is the case not only for the E. coli fim gene cluster (a paralogue) but also for the E. coli sfm gene cluster (an orthologue) (Fig. 2). In addition, the arrangements of genes in the gene cluster of C. freundii and the fim determinant of E. coli differed substantially (Fig. 2). Moreover, some genes are exclusively present either in the C. freundii gene cluster (e.g., the homologue of fimY) or in the E. coli fim determinant (e.g., fimB and fimE) (Fig. 2). The high homology of the cloned invasion genes of C. freundii as well as of the deduced amino acid sequence with the fim genes and the Fim proteins of Salmonella implied that this determinant represented a fim gene cluster. To further support this conclusion, yeast agglutination tests were performed with the recombinant E. coli strains HB101 and AAEC189 carrying plasmid pTO3. As is typical for Fim-mediated yeast agglutination, agglutination was observed for both strains only in the absence of mannose. Therefore, the 10 genes with high homology to S. enterica serovar Typhimurium fim genes were termed fimCf (Fig. 1). No agglutination at all was found for control strains carrying the plasmid vector pBR322.

FIG. 2.

Comparison of the genetic organization of the fim gene cluster from C. freundii strain 3009 to those from S. enterica serovar Typhimurium strain LT2 and E. coli K-12 strain MG1655, as well as to the sfm operon of E. coli MG1655 (an orthologue to the S. enterica serovar Typhimurium fimACDHF operon). The percent identity was determined by performing alignments by using CLUSTALW. n, number of nucleotides; aa, number of amino acids; *, percent identity either between S. enterica serovar Typhimurium and C. freundii or between E. coli and C. freundii.

Invasion efficiencies mediated by various adhesins.

The high homology with fim genes of Salmonella and the property of mannose-sensitive yeast agglutination raised the question of whether other adhesin determinants might also mediate invasion in the experimental setting used. Therefore, invasion assays were performed with recombinant E. coli HB101 strains each expressing one of various adhesins (Table 3). Adhesin expression was demonstrated for all adhesin determinants by ELISA (data not shown), and the adherence efficiency was quantified (Table 4). Although all adhesins were expressed and mediated adherence, not even the highly homologous Salmonella fim cluster was able to render the recombinant HB101 strain invasive. Only the cloned C. freundii fimCf determinant mediated invasion into T24 and RT112 human bladder epithelial cells (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Internalization efficiencies of C. freundii strain 3009 and recombinant E. coli HB101 strains expressing different adhesin determinants with human bladder epithelial cell lines T24 and RT112

| Plasmid or strain | Encoded adhesina | Internalization efficiencyb with: |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| T24 cells | RT112 cells | ||

| pBR322 | None | 0.020 | 0.0007 |

| pPIL110-54 | F1C | 0.020 | <0.0007 |

| pMMP658-6 | Sfr | 0.007 | <0.0007 |

| pANN801-13 | SfaI | 0.010 | <0.0007 |

| pAZZ50 | SfaII | 0.050 | 0.0008 |

| pGB30 | FimEc | 0.020 | <0.001 |

| pISF101 | FimSt | 0.002 | NDc |

| pTO3 | FimCf | 9.7 | 3.1 |

| C. freundii 3009 | FimCf | 11.4 | 27.3 |

FimEc, type 1 pili from E. coli; FimSt, type 1 pili from S. enterica serovar Typhimurium; FimCf, type 1 pili from C. freundii.

The internalization efficiency is given as the percentage of the inoculum surviving gentamicin treatment. Data are the results of one of three indepently performed assays with similar outcomes.

ND, not determined.

TABLE 4.

Efficiencies of adherence of various recombinant E. coli strains and C. freundii to RT112 and T24 human bladder epithelial cells

| Strain | Adhesin expressed | Adhering bacteria per well (103)a with: |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| RT112 cells | T24 cells | ||

| E. coli | |||

| HB101(pBR322) | None | 12.0 ± 4.3 | 10.0 ± 2.8 |

| HB101(pPIL110-54) | F1C | 126.7 ± 41.1 | 210.0 ± 64.8 |

| HB101(pMMP658-6) | Sfr | 533.3 ± 124.7 | 531.3 ± 196.9 |

| HB101(pANN801-13) | SfaI | 416.7 ± 62.4 | 376.7 ± 33.0 |

| HB101(pAZZ50) | SfaII | 1020.0 ± 58.9 | 170.0 ± 21.6 |

| HB101(pGB30) | FimEc | 493.3 ± 163.6 | 250.0 ± 40.8 |

| HB101(pISF101) | FimSt | 160.0 ± 28.3 | 116.7 ± 17.1 |

| HB101(pTO3) | FimCf | 60.7 ± 10.9 | 160.9 ± 65.6 |

| C. freundii 3009 | FimCf | 202.0 ± 20.4 | 333.3 ± 84.9 |

Data are means ± standard deviations.

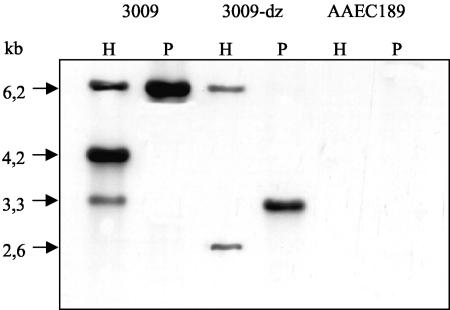

Determination of essential invasion genes.

Sequence analysis of the fimCf gene cluster was the prerequisite for defined subcloning experiments and subsequent tests of the resulting transformants for invasiveness. Constructs no longer carrying fimUCf, fimWCf, and fimYCf (Fig. 1, pPH1) and in addition fimZCf (Fig. 1, pB7-3) still mediated invasiveness and mannose-sensitive yeast agglutination (Fig. 1). The corresponding fim genes in Salmonella are known to have regulatory functions (42). Obviously, these fimCf genes are dispensable for the expression of adhesiveness and invasiveness. In contrast, further truncation of the insert of plasmid pB7-3 containing fimACf, fimICf, fimCCf, fimDCf, fimHCf, and fimFCf at either the fimACf end (Fig. 1, pPH19) or the fimFCf end (Fig. 1, pAA8) resulted in the loss of adhesiveness and invasiveness (Fig. 1). Similarly, the insertion of an IS1 element in fimACf resulted in the loss of adhesiveness and invasiveness (Fig. 1). The conclusion was drawn from these results that genes fimACf to fimFCf, represented by the insert of plasmid pB7-3, were sufficient for mediating invasiveness and mannose-sensitive yeast agglutination. Inactivation of the fim determinant in C. freundii strain 3009 by deletion of the central part resulted in a mutant (3009-dz) lacking part of fimDCf and the genes fimHCf, fimFCf, and fimZCf. The deletion was verified by PCR and Southern blotting (Fig. 3). The invasion efficiency in T24 cells of the mutant 3009-dz was reduced by 79% compared to that of the wild-type strain 3009. Introduction of plasmid pPH23, carrying fimDCf, fimHCf, fimFCf, and fimZCf (Table 1), restored invasiveness to 62% of the wild-type level. Obviously, the fimCf determinant is essential for efficient invasiveness of C. freundii strain 3009.

FIG. 3.

Southern blot of HindIII (lanes H)- and PstI (lanes P)-digested chromosomal DNAs of wild-type strain C. freundii 3009, mutant 3009-dz (lacking part of fimDCf and genes fimHCf to fimZCf), and control strain E. coli AAEC189 (in which the complete fimEc operon is deleted [5]). The 6.2-kb PstI fragment from plasmid pPH1 (Fig. 1) carrying fimICf to fimFCf was used as a probe.

In vivo studies.

The ability of C. freundii 3009 to invade and replicate in human brain microvascular endothelial cells has been described previously (1). In addition, C. freundii is known to cause neonatal meningitis (12). We next examined the abilities of the wild-type C. freundii strain 3009 and the recombinant E. coli K-12 strain HB101(pPH1), harboring the fimCf genes, and the control strain HB101(pSU19) to penetrate into the cerebrospinal fluid in the newborn rat model (Table 5). As shown in Table 5, the magnitudes of bacteremia were similar in animals infected with HB101(pPH1) or HB101(pSU19). However, the occurrence of meningitis (defined as positive cerebrospinal fluid cultures) was significantly lower (P < 0.05) in animals receiving HB101(pSU19) (3 of 14; 21%) than in those receiving HB101(pPH1) (14 of 20; 70%).

TABLE 5.

Effect of the fimCf determinant on the ability to reach the cerebrospinal fluid in the neonatal rat model

| Strain | Bacteremia (log CFU/ml of blood)a | No. of animals with positive cerebrospinal fluid culture/total |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli HB101(pSU19) | 5.31 ± 0.87 | 3/14b |

| E. coli HB101(pPH1) | 5.42 ± 0.71 | 14/20 |

| C. freundii 3009 | 6.33 ± 1.02 | 7/10 |

Data are means ± standard deviations.

P < 0.05 by Fisher's exact test.

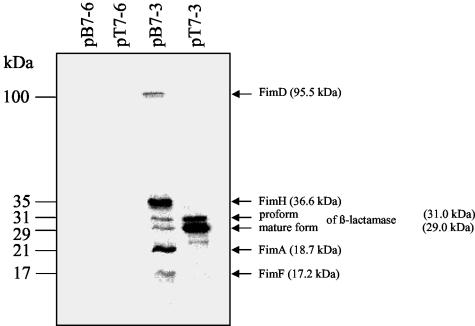

FimCf expression.

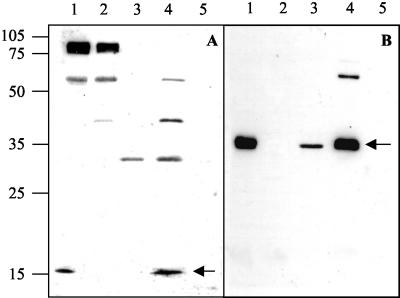

The BamHI/XhoI fragment of pTO3 (Fig. 1) containing fimACf to fimFCf was cloned into the expression vector pT7-3 under the control of the phage T7 promoter φ10, resulting in plasmid pB7-3, and into pT7-6 antiparallel to the φ10 promoter, creating pB7-6 (Fig. 1). These constructs as well as control plasmids were introduced into strain BL21DE3(pLysS). 35S-labeled proteins were detected by autoradiography after separation by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. The molecular masses of the observed proteins were 100, 35, 31, 29, 21, and 17 kDa (Fig. 4). These values were in good agreement with the molecular masses calculated by employing SWISS-PROT (http://www.expasy.ch/sprot) for FimDCf (95.5 kDa), FimHCf (36.3 kDa), FimFCf (17.2 kDa), and the proform and the mature form of the β-lactamase encoded by pT7-3 (31 and 29 kDa), respectively. Only for the molecular mass of FimACf determined by autoradiography (21 kDa) and deduced from the DNA sequence (18.7 kDa) was a discrepancy observed. Protein bands representing proteins with the molecular masses of FimICf (18.1 kDa) and the chaperone FimCCf (25.1 kDa) could not be detected (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Autoradiography after SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis of whole-cell lysates of E. coli BS21(pLysS) harboring recombinant plasmids. Proteins specifically expressed under control of the T7 promoter φ10 were labeled with 35S (see Materials and Methods) and separated on a 13% polyacrylamide gel by electrophoresis. The plasmids employed are indicated above the lanes. Molecular masses are indicated on the left. The most likely identities of the proteins, estimated by the molecular mass closest to the one deduced from the nucleotide sequence, are indicated at the right.

In addition, FimFCf and FimHCf could be detected in Western blots with anti-FimFCf and anti-FimHCf rabbit sera in heat-extracted proteins of E. coli BL21(DE3)(pLysS)(pB7-3) and AAEC189(pPH1) (Fig. 5). These recombinant strains contained plasmids carrying fimACf to fimFCf and fimACf to fimZCf, respectively (Fig. 1). No proteins were detected with the control strains BL21(DE3)(pLysS)(pT7-3) and AAEC189 with anti-FimHCf serum. However, the anti-FimHCf serum cross-reacted with FimHEc of the E. coli K-12 strain DH5α due to a sequence in FimHEc with 73% identity with the sequence of the peptide used to raise the antiserum (Fig. 5). The anti-FimFCf serum was not as specific, because it also recognized a few other protein bands representing proteins with molecular masses of >17 kDa from the control strains not expressing any Fim proteins (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

Western blots of heat-extracted proteins transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane and probed with anti-FimFCf (A) and anti-FimHCf (B) sera. In panel A the protein band representing FimF (17 kDa) is indicated by an arrow. In panel B the arrow designates a polypeptide of about 36 kDa (FimH). Molecular masses of standard proteins, in kilodaltons, are indicated at the left. Lanes: 1, E. coli BL21(pLysS)(pB7-3); 2, E. coli BL21(pLysS)(pT7-3); 3, E. coli DH5α; 4, E. coli AAEC189(pPH1); 5, E. coli AAEC189.

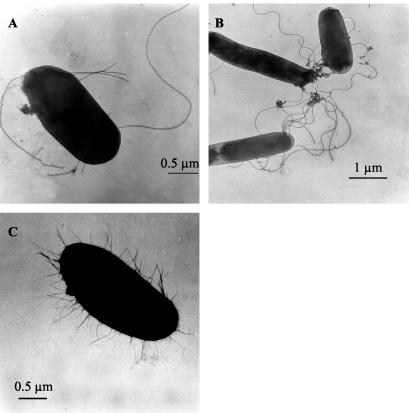

Detection of pili.

In order to demonstrate the expression of pili by C. freundii strain 3009, specimens with this strain were negatively stained and inspected by transmission electron microscopy. The C. freundii culture as well as the other Fim-expressing strains used showed mannose-sensitive yeast agglutination, indicating the expression of the type 1 adhesin. The expression of other adhesins was demonstrated by ELISA and in adhesion assays (see Materials and Methods). Pili could be demonstrated for all of the recombinant E. coli HB101 strains tested, with one exception. E. coli strain HB101(pTO3), carrying the fim gene cluster from C. freundii, was bare; i.e., no pili could be detected at its surface. Similarly, C. freundii 3009 also showed no pili; however, flagella were clearly visible (Fig. 6).

FIG. 6.

Transmission electron microscopic images of C. freundii strain 3009 (A), E. coli strain AAEC189(pPH1) (B), and E. coli strain DH5α (C). The cultures of all strains used for the photographs presented here showed mannose-sensitive yeast agglutination.

Carbohydrate residues involved in C. freundii internalization and yeast agglutination.

In general, certain carbohydrate residues on the surfaces of host cells function as adhesin receptors during the establishment of an infection. Besides mannose residues, which constitute the receptor structure for type 1 pili, several other carbohydrates were tested for interference with yeast agglutination and invasion of T24 cells. Invasion by C. freundii strain 3009 was inhibited by more than 80% only in the presence of 100 mM mannose, 100 mM GlcNAc, and 0.6 mg of chitin hydrolysate (i.e., a mixture of GlcNAc oligomers of various sizes) per ml. For chitin hydrolysate, dose-dependent inhibition of Citrobacter invasion was demonstrated (Fig. 7). No inhibition was observed in the presence of glucose, galactose, fucose, or N-acetylneuraminic acid (data not shown). The invasion efficiency of S. enterica serovar Typhimurium strain C17 was not affected by any of the carbohydrates employed (Fig. 7). Interestingly, yeast agglutination by C. freundii strain 3009 was blocked only by mannose and not by any other carbohydrates tested.

FIG. 7.

Dose-dependent inhibition of C. freundii strain 3009 internalization into human bladder epithelial (T24) cells by chitin hydrolysate. S. enterica serovar Typhimurium strain C17 internalization was not inhibited. Results are presented as means ± standard deviations.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have identified and characterized an invasion determinant from C. freundii strain 3009 with high homology to the Salmonella fim gene cluster, encoding type 1 fimbriae. This was surprising, because Citrobacter is considered to be only distantly related to Salmonella (28). Although the fim determinant of S. enterica serovar Typhimurium is necessary for efficient invasion of HeLa cells, the corresponding type 1 pili are not sufficient to mediate invasion (4). This is in concordance with our observation that adherence mediated by neither the fim determinant from E. coli strain 536 carried by plasmid pGB30 nor that from S. enterica serovar Typhimurium strain LT2 resulted in internalization of bacteria. Deletion of the central part of the invasion determinant in Citrobacter, however, reduced invasiveness fivefold, whereas genes fimACf to fimFCf imparted invasiveness to noninvasive E. coli K-12 strains. These data strongly implicate the FimCf adhesin as the critical factor involved in uptake of C. freundii and recombinant E. coli strains by human T24 bladder epithelial cells.

As expected, the fimCf determinant was shown to be responsible for mannose-sensitive yeast agglutination. However, in spite of the high homology with the Salmonella fim gene cluster and the ability to mediate yeast agglutination, we were not able to demonstrate the presence of pili on C. freundii strain 3009 or any of the recombinant E. coli strains harboring the fimCf determinant. This resembles the situation of the Dr family of adhesins. This adhesin family consists of afimbrial and fimbrial members with high amino acid sequence homology for genes A to D, encoding the chaperon and usher as well as the subunit proteins constituting the adhesin. The cause for the assembly of some of them into fimbriae while others are afimbrial adhesins is unclear (48).

The presence of a fim gene cluster with identical gene order and high homology at the nucleotide level to that of Salmonella might reflect horizontal transfer of this unit either from Salmonella to Citrobacter or vice versa, or fim may be ancestral to Citrobacter, E. coli, and Salmonella (9). If the first hypothesis is correct, then after acquisition of the fim determinant by Citrobacter, it extended its function and the Fim subunit proteins were no longer assembled into a fimbrial structure. The new function was not just to direct adherence but also to direct invasion. Such a dual function of an adhesin, mediating adherence and invasion, is not a rare exception and is documented for a variety of adhesins, not just those of enterobacterial species (reviewed in reference 32).

The ability to invade host cells by expressing a Fim adhesin might well be employed by Citrobacter in vivo. As has been reported for uropathogenic E. coli in the mouse model, C. freundii might invade urothelial cells during a urinary tract infection (31). In addition, invasiveness could be used by C. freundii to initiate transcytosis and to cross the blood-brain barrier to cause neonatal meningitis. This can be hypothesized by taking into account that both C. freundii strain 3009 and a recombinant E. coli K-12 strain harboring the essential genes for invasiveness of the fimCf gene cluster were able to invade human epithelial and endothelial cells in vitro and crossed the blood-brain barrier in the rat pup model. These findings were also supported by a report by Badger et al. (1) demonstrating that C. freundii 3009 was able to invade, transcytose, and replicate inside human brain microvascular endothelial cells in vitro.

The mannose binding capacity of the FimHCf protein is essential for mediating efficient invasion by C. freundii as well as by the recombinant E. coli strains harboring the fimCf determinant. This was also reported for FimHEc of uropathogenic E. coli strain NU14, which is able to invade the human bladder epithelial cell line 5637 only in the absence of mannose (29). However, not every fimEc determinant is able to mediate invasion. The fimEc determinant, e.g., from E. coli 536 encoded by plasmid pGB30, did not mediate invasion. For fimH, single-nucleotide polymorphisms with adaptive advantage have been discovered in E. coli and Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (6, 46). These polymorphisms are most likely responsible for the observed discrepancies between different fim determinants regarding the ability to mediate adherence with different efficiencies and for certain sequence variants in E. coli directing invasion (4, 47).

Besides mannose, there are several other carbohydrate residues that are frequently found as part of the glycocalyx of host cells, which might serve as receptors for bacterial adhesins. We tested fucose, galactose, GlcNAc, glucose, and N-acetylneuraminic acid for inhibitory effects on FimCf-conducted invasion. None of the tested carbohydrates except GlcNAc showed an adverse effect. An anti-invasion effect for GlcNAc has also been reported for invasive Klebsiella pneumoniae strains (15). As for Klebsiella, a mixture of GlcNAc oligomers (i.e., chitin hydrolysate) produced a more pronounced inhibition of invasion than did GlcNAc monomers. In contrast to C. freundii invasion, Klebsiella invasion was not inhibited by mannose. There are no reports about the role of GlcNAc in invasion mediated by E. coli type 1 fimbriae. However, GlcNAc is the receptor structure recognized by several E. coli adhesins as F17 and K88 fimbriae (13, 17). Studies are in progress to clarify whether inhibition by GlcNAc of C. freundii invasion is due to a second binding capacity of FimHCf or whether another FimCf subunit protein is involved in the invasion process by binding to GlcNAc.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by DFG grant Oe 135/3-2, grant SFB 479, and Graduiertenkolleg Infektiologie.

We are thankful to M. Keller (University of Bielefeld), S. P. Kidd (University of Birmingham), and A. Bäumler (Texas A&M University) for plasmids pK19mob, pJP5603, and pISF101, respectively. We thank J. Sheperd for help with sequence annotation, A. Reisenauer for support with invasion assays in the presence of carbohydrates, and C. A. Wass for technical assistance with the animal experiments.

Editor: J. T. Barbieri

REFERENCES

- 1.Badger, J. L., M. F. Stins, and K. S. Kim. 1999. Citrobacter freundii invades and replicates in human brain microvascular endothelial cells. Infect. Immun. 67:4208-4215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baorto, D. M., Z. Gao, R. Malaviya, M. L. Dustin, A. van der Merwe, D. M. Lublin, and S. N. Abraham. 1997. Survival of FimH-expressing enterobacteria in macrophages relies on glycolipid traffic. Nature 389:636-639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bartolome, B., Y. Jubete, E. Martinez, and F. de la Cruz. 1991. Construction and properties of a family of pACYC184-derived cloning vectors compatible with pBR322 and its derivatives. Gene 102:75-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bäumler, A. J., R. M. Tsolis, and F. Heffron. 1996. Contribution of fimbrial operons to attachment to and invasion of epithelial cell lines by Salmonella typhimurium. Infect. Immun. 64:1862-1865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blomfield, I. C., M. S. McClain, and B. I. Eisenstein. 1991. Type 1 fimbriae mutants of Escherichia coli K-12: characterization of recognized afimbriate strains and construction of new fim deletion mutants. Mol. Microbiol. 5:1439-1445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boddicker, J. D., N. A. Ledeboer, J. Jagnow, B. D. Jones, and S. Clegg. 2002. Differential binding to and biofilm formation on HEp-2 cells by Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium is dependent upon allelic variation in the fimH gene of the fim gene cluster. Mol. Microbiol. 45:1255-1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bolivar, F., R. L. Rodriguez, P. J. Greene, M. C. Betlach, H. L. Heyneker, and H. W. Boyer. 1977. Construction and characterization of new cloning vehicles. II. A multipurpose cloning system. Gene 2:95-113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boxberger, H. J., and T. F. Meyer. 1994. A new method for the 3-D in vitro growth of human RT112 bladder carcinoma cells using the alginate culture technique. Biol. Cell 82:109-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boyd, E. F., and D. L. Hartl. 1999. Analysis of the type 1 pilin gene cluster fim in Salmonella: its distinct evolutionary histories in the 5′ and 3′ regions. J. Bacteriol. 181:1301-1308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boyer, H. W., and D. Roulland-Dussoix. 1969. A complementation analysis of the restriction and modification of DNA in Escherichia coli. J. Mol. Biol. 41:459-472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clegg, S., B. K. Purcell, and J. Pruckler. 1987. Characterization of genes encoding type 1 fimbriae of Klebsiella pneumoniae, Salmonella typhimurium, and Serratia marcescens. Infect. Immun. 55:281-287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Doran, T. I. 1999. The role of Citrobacter in clinical disease of children. Clin. Infect. Dis. 28:384-394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.el Mazouari, K., E. Oswald, J. P. Hernalsteens, P. Lintermans, and H. De Greve. 1994. F17-like fimbriae from an invasive Escherichia coli strain producing cytotoxic necrotizing factor type 2 toxin. Infect. Immun. 62:2633-2638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elsinghorst, E. A. 1994. Measurement of invasion by gentamicin resistance. Methods Enzymol. 236:405-420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fumagalli, O., B. D. Tall, C. Schipper, and T. A. Oelschlaeger. 1997. N-glycosylated proteins are involved in efficient internalization of Klebsiella pneumoniae by cultured human epithelial cells. Infect. Immun. 65:4445-4451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goluszko, P., V. Popov, R. Selvarangan, S. Nowicki, T. Pham, and B. J. Nowicki. 1997. Dr fimbriae operon of uropathogenic Escherichia coli mediates microtubule-dependent invasion to the HeLa epithelial cell line. J. Infect. Dis. 176:158-167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grange, P. A., M. A. Mouricout, S. B. Levery, D. H. Francis, and A. K. Erickson. 2002. Evaluation of receptor binding specificity of Escherichia coli K88 (F4) fimbrial adhesin variants using porcine serum transferrin and glycosphingolipids as model receptors. Infect. Immun. 70:2336-2343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hacker, J., H. Kestler, H. Hoschützky, K. Jann, F. Lottspeich, and T. K. Korhonen. 1993. Cloning and characterization of the S fimbrial adhesin II complex of an Escherichia coli O18:K1 meningitis isolate. Infect. Immun. 61:544-550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hacker, J., M. Ott, G. Blum, R. Marre, J. Heesemann, H. Tschäpe, and W. Goebel. 1992. Genetics of Escherichia coli uropathogenicity: analysis of the O6:K15:H31 isolate 536. Zentbl. Bakteriol. 276:165-175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hacker, J., G. Schmidt, C. Hughes, S. Knapp, M. Marget, and W. Goebel. 1985. Cloning and characterization of genes involved in production of mannose-resistant, neuraminidase-susceptible (X) fimbriae from a uropathogenic O6:K15:H31 Escherichia coli strain. Infect. Immun. 47:434-440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hanahan, D. 1983. Studies on transformation of Escherichia coli with plasmids. J. Mol. Biol. 166:557-580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hess, P., N. Daryab, K. Michaelis, A. Reisenauer, and T. A. Oelschlaeger. 2000. Type 1 pili of Citrobacter freundii mediate invasion into host cells. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 485:225-235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jouve, M., M. I. Garcia, P. Courcoux, A. Labigne, P. Gounon, and C. Le Bouguenec. 1997. Adhesion to and invasion of HeLa cells by pathogenic Escherichia coli carrying the afa-3 gene cluster are mediated by the AfaE and AfaD proteins, respectively. Infect. Immun. 65:4082-4089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khan, A. S., B. Kniep, T. A. Oelschlaeger, I. Van Die, T. Korhonen, and J. Hacker. 2000. Receptor structure for F1C fimbriae of uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 68:3541-3547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khan, A. S., I. Mühldorfer, V. Demuth, U. Wallner, T. K. Korhonen, and J. Hacker. 2000. Functional analysis of the minor subunits of S fimbrial adhesion (SfaI) in pathogenic Escherichia coli. Mol. Gen. Genet. 263:96-105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khan, A. S., and D. M. Schifferli. 1994. A minor 987P protein different from the structural fimbrial subunit is the adhesin. Infect. Immun. 62:4233-4243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Laemmli, U. K. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227:680-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lawrence, J. G., D. L. Hartl, and H. Ochman. 1991. Molecular considerations in the evolution of bacterial genes. J. Mol. Evol. 33:241-250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martinez, J. J., M. A. Mulvey, J. D. Schilling, J. S. Pinkner, and S. J. Hultgren. 2000. Type 1 pilus-mediated bacterial invasion of bladder epithelial cells. EMBO J. 19:2803-2812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meier, C., T. A. Oelschlaeger, H. Merkert, T. K. Korhonen, and J. Hacker. 1996. Ability of Escherichia coli isolates that cause meningitis in newborns to invade epithelial and endothelial cells. Infect. Immun. 64:2391-2399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mulvey, M. A., Y. S. Lopez-Boado, C. L. Wilson, R. Roth, W. C. Parks, J. Heuser, and S. J. Hultgren. 1998. Induction and evasion of host defenses by type 1-piliated uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Science 282:1494-1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oelschlaeger, T. A. 2001. Adhesins as invasins. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 291:7-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oelschlaeger, T. A., P. Guerry, and D. J. Kopecko. 1993. Unusual microtubule-dependent endocytosis mechanisms triggered by Campylobacter jejuni and Citrobacter freundii. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90:6884-6888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pawelzik, M., J. Heesemann, J. Hacker, and W. Opferkuch. 1988. Cloning and characterization of a new type of fimbria (S/F1C-related fimbria) expressed by an Escherichia coli O75:K1:H7 blood culture isolate. Infect. Immun. 56:2918-2924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Penfold, R. J., and J. M. Pemberton. 1992. An improved suicide vector for construction of chromosomal insertion mutations in bacteria. Gene 118:145-146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pham, T. Q., P. Goluszko, V. Popov, S. Nowicki, and B. J. Nowicki. 1997. Molecular cloning and characterization of Dr-II, a nonfimbrial adhesin-I-like adhesin isolated from gestational pyelonephritis-associated Escherichia coli that binds to decay-accelerating factor. Infect. Immun. 65:4309-4318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Roe, A. J., C. Currie, D. G. E. Smith, and D. L. Gally. 2001. Analysis of type 1 fimbriae expression in verotoxigenic Escherichia coli: a comparison between serotypes O157 and O26. Microbiology 147:145-152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sanger, F., S. Nicklen, and A. R. Coulson. 1977. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 74:5463-5467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schäfer, A., A. Tauch, W. Jäger, J. Kalinowski, G. Thierbach, and A. Pühler. 1994. Small mobilizable multi-purpose cloning vectors derived from the Escherichia coli plasmids pK18 and pK19: selection of defined deletions in the chromosome of Corynebacterium glutamicum. Gene 145:69-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Studier, F. W. 1991. Use of bacteriophage T7 lysozyme to improve an inducible T7 expression system. J. Mol. Biol. 219:37-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tabor, S., and C. C. Richardson. 1985. A bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase/promoter system for controlled exclusive expression of specific genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 82:1074-1078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tinker, J. K., and S. Clegg. 2001. Control of FimY translation and type 1 fimbrial production by the arginine tRNA encoded by fimU in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Mol. Microbiol. 40:757-768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Towbin, H., T. Staehelin, and J. Gordon. 1979. Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets: procedure and some applications. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 76:4350-4354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.van Die, I., B. van Geffen, W. Hoekstra, and H. Bergmans. 1985. Type 1C fimbriae of a uropathogenic Escherichia coli strain: cloning and characterization of the genes involved in the expression of the 1C antigen and nucleotide sequence of the subunit gene. Gene 34:187-196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang, Y., S. H. Huang, C. A. Wass, M. F. Stins, and K. S. Kim. 1999. The gene locus yijP contributes to Escherichia coli K1 invasion of brain microvascular endothelial cells. Infect. Immun. 67:4751-4756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Weissman, S. J., S. L. Moseley, D. E. Dykhuizen, and E. V. Sokurenko. 2003. Enterobacterial adhesins and the case for studying SNPs in bacteria. Trends Microbiol. 11:115-117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wilson, R. L., J. Elthon, S. Clegg, and B. D. Jones. 2000. Salmonella enterica serovars Gallinarum and Pullorum expressing Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium type 1 fimbriae exhibit increased invasiveness for mammalian cells. Infect. Immun. 68:4782-4785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang, L., B. Foxman, P. Tallman, E. Cladera, C. Le Bouguenec, and C. F. Marrs. 1997. Distribution of drb genes coding for Dr binding adhesins among uropathogenic and fecal Escherichia coli isolates and identification of new subtypes. Infect. Immun. 65:2011-2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]