Abstract

Sturge-Weber syndrome (SWS) is a rare neurocutaneous syndrome characterised by facial naevus and leptomeningeal angiomatosis resulting in neurological and ophthalmological complications. In its rare variant, SWS type 3, the clinical hallmark of facial naevus is absent which poses a diagnostic challenge. Here, we present an interesting case of SWS type 3 where a child presented twice with prolonged severe unilateral headache mimicking migraine status followed on both occasions with focal seizures. He developed a dense right-sided homonymous hemianopia, and an urgent brain MRI scan was performed which pointed towards the diagnosis of SWS type 3.

Background

Sturge-Weber syndrome (SWS) is a rare, non-familial, neurocutaneous syndrome characterised by facial port-wine naevus and leptomeningeal angiomatosis resulting in neurological and ophthalmological complications. Recently, it has been described that SWS is caused by somatic mutation in GNAQ gene that regulates intracellular signalling pathways.1 SWS is divided into three subtypes. Type 1 comprises facial and leptomeningeal angioma;2 type 2 exhibits facial angioma without evident intracranial involvement, whereas type 3 has leptomeningeal angiomas without facial naevus and usually no ocular manifestation. There have only been a small number of cases of SWS type 3 reported in the literature who are characterised by a vascular abnormality in the brain3 with no neurocutaneous markers or glaucoma.

SWS has a variety of presentations, including seizures, hemiparesis, glaucoma and mental retardation, which when associated with facial naevus are indicative of the syndrome. Facial port-wine stain, involving the ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve, is the commonest clinical presentation. 72% of cases have a unilateral naevus that is ipsilateral to the intracranial lesion.4

The diagnosis of SWS is confirmed with neuroimaging demonstrating angiomatosis. A common radiological sign of SWS is ‘tram-line’ calcification. Calcification is not present in all patients with SWS. The hallmark of SWS intracranial involvement is leptomeningeal contrast enhancement, and the presence of calcification without SWS intracranial blood vessel abnormalities may indicate other aetiologies. Since SWS type 3 has no neurocutaneous marker and a variety of potential presenting symptoms, a high degree of suspicion is required for diagnosis. We discuss a case of SWS type 3 presenting as migraine status at presentation.

Case presentation

We report a 9-year-old boy who presented with a 24-hour history of vomiting and severe left temporal throbbing headache. The headache did not alter with position and was constant throughout the day and night. There was no visual disturbance or photophobia and he was otherwise physically well. There was no history of concurrent illness or trauma.

His medical history was remarkable with a similar history 3 years prior to this admission, aged 6. He presented with a 4-day history of severe left-sided headache in conjunction with a presumed viral illness. He developed vomiting and right-sided focal seizures on the fourth day of headache instigating hospital admission. His eyes deviated to the right with right upper and lower limb jerking movements followed by weakness and decreased conscious level. His seizure progressed to secondary generalised seizure involving upper and lower limbs. He received intravenous benzodiazepine and phenytoin, which stopped the seizure after 60 min. He was intubated and ventilated in view of respiratory depression following the prolonged seizure. Owing to suspected encephalitis, he was treated with intravenous aciclovir and intravenous ceftriaxone.

His CT head without contrast was normal and his EEG showed left hemispheric slow-wave abnormality with no epileptiform discharges which was presumed to be suggestive of encephalitis. His blood and cerebrospinal fluid investigations were completely normal, and he made a rapid recovery and was extubated after 12 hours. His non-contrast brain MRI scan did not demonstrate any acute parenchymal abnormality. He was discharged home after 1 week and had no other significant medical events prior to this admission.

There was no significant family history; his father had suffered from migraines briefly as a child.

On assessment at admission this time, he was of normal build, scored 15/15 on the Glasgow Coma Scale and had an unremarkable systemic examination. His oxygen saturations were 99% in air, heart rate was 78/min, respiratory rate was 21/min and blood pressure was 97/57 mm Hg with a mean of 70, a systemic BP of 90–110 mm Hg being normal in this age range. His temperature was 36.5°C and blood glucose was 5.8 mmol/L on near-patient testing. He was indicating a painful left fronto-temporal region. Other than this, his detailed neurological examination was unremarkable with no other signs of raised intracranial pressure. He had normal pupils and pupillary responses with normal fundi. There were no neurocutaneous markers.

Routine blood examinations at admission were not suggestive of infection, and an urgent CT head with contrast was performed because of continued headache and vomiting. This showed focal areas of cortical/subcortical calcification in the left occipital lobe. There was no abnormality on contrast enhancement. Initial impressions were that the appearances were consistent with postencephalitic laminar calcification. The headache, nausea and vomiting persisted for 3 days despite regular analgesia (paracetamol, ibuprofen and oramorph when required) and antiemetics (cyclizine and domperidone). Serial neurological examinations were performed and, on day 3 of his illness, a right-sided homonymous hemianopia was found on examination of the cranial nerves. This was later confirmed by ophthalmology. He had no other new neurological findings. MRI/magnetic resonance angiogram (MRA) with contrast was performed which revealed pial angiomatosis in the left occipital and parietal lobe consistent with the diagnosis of SWS and in the absence of any neurocutaneous markings classified this as SWS type 3. He was an inpatient for 6 days and was discharged once his headache resolved with neurology and ophthalmology follow-up arranged.

However, he was readmitted 8 days later with recurrence of severe headache, sudden acute confusion and decreasing conscious level. An urgent CT scan was performed, which did not show an acute haemorrhage and was reported as unchanged when compared with his previous scan. The differential diagnosis was a complex partial seizure, which responded well to loading dose intravenous phenytoin. He recovered gradually over 2 hours and was reported to be back to his normal self. He had an EEG which showed continuous slow-wave activity over the left temporal quadrant indicating a focal dysfunctional area. He was started on antiepileptic medication levetiracetam as having had two seizures with a confirmed diagnosis of SWS he had a high chance of seizure recurrence. His headache improved while his visual field defect remained with a slight improvement in the right temporal and nasal field of vision.

Investigations

Standard blood testing revealed normal urea and electrolytes, liver function tests and bone profile. His C reactive protein was <5 mg/L (0–10 normal range). His full blood count was unremarkable except for neutrophils of 10.58×109/L (1.5–8), which were 4.66×109 2 days later. He had a normal international normalised ratio (INR) and activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT).

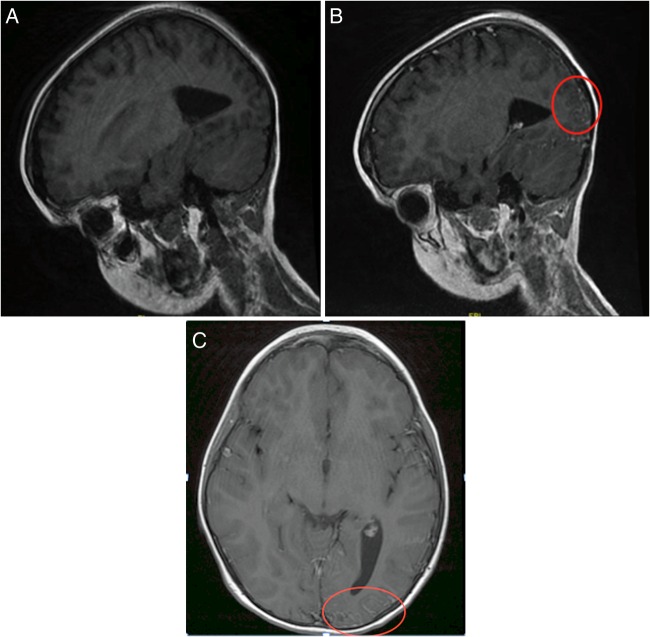

CT head (figure 1) with contrast showed calcification in his left occipital cortical and subcortical lobe; as he had previously been treated for presumed encephalitis, these findings were initially attributed to that event but was later revised after MRI brain findings.

Figure 1.

CT head showing focal areas of cortical/subcortical calcification in the left occipital lobe.

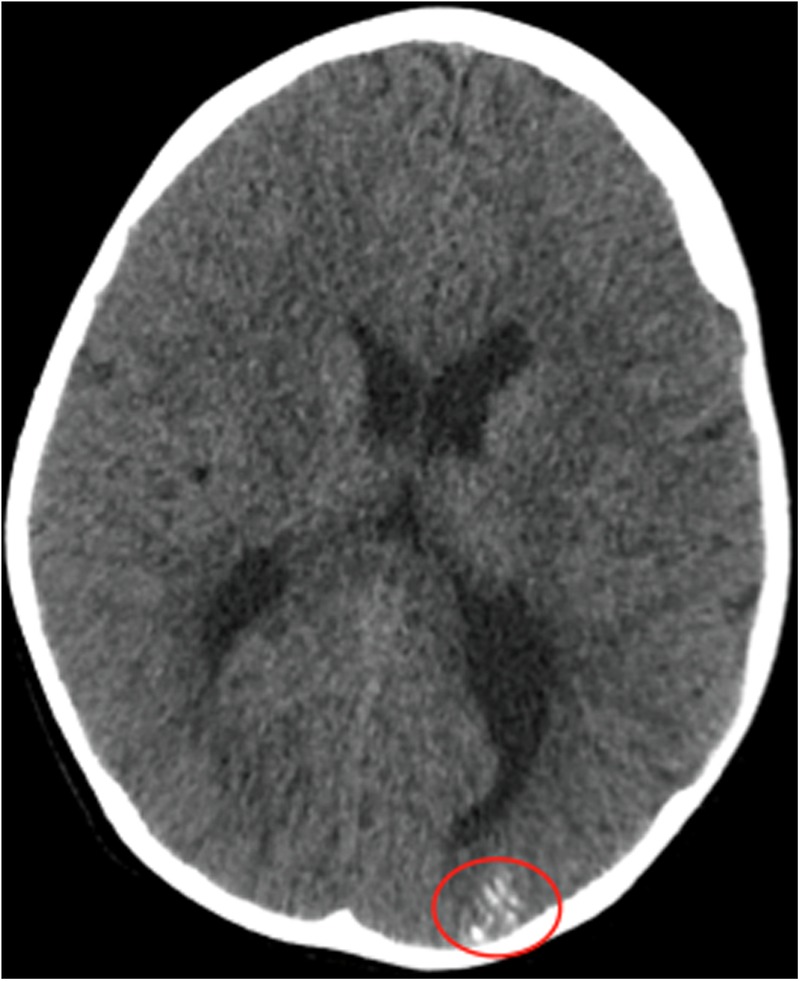

Urgent MRI brain (figure 2A–C) with contrast showed pial angiomatosis in the occipital and parietal lobes along with atrophy of underlying cortex. This finding plus the CT head finding of calcification in the corresponding area is consistent with the diagnosis of SWS. In the absence of facial port-wine naevus and glaucoma, this was classified as type 3.

Figure 2.

(A) MRI head—precontrast sagittal section. MRI head—postcontrast sagittal section (B) and postcontrast axial imaging (C)—showing leptomeningeal enhancement within subarachnoid spaces/sulci of occipital and parietal lobe that is consistent with pial angiomatosis.

EEG on readmission showed almost continuous slow delta wave activity over left posterior quadrant, indicating a focal dysfunctional area. At times, there were suspicious components intermixed with slow activity over the left but there was no obvious epileptiform discharges.

Differential diagnosis

One should consider the primary and secondary causes of headache.

Probable migraine (without aura): the presentation of 24 hours history of unilateral throbbing headache, severe intensity and vomiting is consistent with probable migraine episode (probable as less than five episodes in total).5

Status migrainosus: as he persisted to have severe unremitting headache for >72 hours, he fulfilled the criteria for status migrainosus.5

Acute intracranial infective process (meningitis/encephalitis): this was unlikely in the absence of fever and normal blood infection markers.

Intracranial mass: this was seriously considered in view of acute onset of severe headache associated with vomiting. Urgent CT head at admission ruled this out.

Intracranial vascular anomaly: once the CT head had picked up calcification, an overlying vascular malformation such as arteriovenous malformation was considered. When, on serial neurological examination, ophthalmolgical signs were elicited further detailed neuroimaging with MRI brain with contrast and MRA was performed. MRA was normal but MRI of the brain with contrast picked up the diagnosis of SWS.

Non-neurological cause of headache to consider:

Post-traumatic headache: no history of trauma.

Acute substance use or exposure, that is, carbon monoxide poisoning: no history of either.

Cranial or localised pathology, that is, sinusitis, otitis media: not indicated by the history or physical examination.

Headache secondary to hypertension: blood pressure within normal range for age

Treatment

Simple analgesics (paracetamol/ibuprofen) for acute symptomatic headaches.

Flunarazine for migraine prophylaxis, in view of recurrent headache episodes.

Levetiracetam has been started after his readmission with possible seizure episode.

Aspirin has been started to reduce the chances of vascular episodes (strokes) in view of pial angiomatosis.

Outcome and follow-up

Since starting on flunarazine, his headache episodes have decreased in frequency and severity. At his 3-month neurology clinic follow-up, he reported of only mild headaches in the preceding month. He still had right homonymous hemianopia but with decreasing density when compared to before. He has not had any further seizures since starting antiepileptic medication (levetiracetam).

Six-month follow-up at ophthalmology, clinic revealed completely normal visual fields and the absence of hemianopia.

Discussion

SWS is a rare, sporadically occurring condition which was first described by Dr William Sturge in 1879 followed by Volland in 1913 and Weber in 1922 who described the intracranial calcification. SWS is characterised by a port-wine stain, leptomeningeal angiomatosis and ophthalmic abnormalities; these are caused by an abnormal persistence of the embryonic vascular system.6 It is believed that this syndrome's possible cause is the formation of a vascular plexus around the cephalic portion of the neural tube.7 Gomez and Bebin8 described the process of ‘Vascular Steal Phenomenon’ developing around angioma, resulting in cortical ischaemia.

Headache in SWS is usually migraine-like and is suffered by 44% of patients but as a presenting feature is rare.9 A study by Prabhakar et al10 showed that almost 35% of patients experiencing headaches have one more than once a month and 25% describe headache impacting on their daily activities. SWS type 3 is a very rare variant of this neurocutaneous disorder, and the paediatric presentation rarely includes headaches and less likely a ‘Status migrainosus.’ It is very important for physician to differentiate migraine attacks from seizures as both can be presenting features in patients with SWS type 3 and differentiation can sometimes be challenging. EEG performed in those patients may show irregularity because of abnormal pial angiomatosis without pathological electrical activity, and physician might end up over treating with antiepileptic medication.

Our case is unique as the presenting symptom was a persistent migraine-like headache on both occasions, which then progressed to neurological symptoms, partial seizure and visual field defects. This prompted neuroimaging.

Huang et al11 described a case of SWS type 3 in a 36-year-old who had been experiencing migraine-like attacks with visual aura and a permanent visual field defect since the age of 10, but unlike our case did not have these symptoms preceding seizure activity. They propose the mechanism for migrainous attacks in SWS to be chronic focal ischaemia and alteration to the venous drainage leading to compromised neuronal function, which may lead to a tendency for migrainous episodes.11 Another similarity was the persistence of the visual field defect after the migraine had resolved. Huang et al discuss various cases of complete resolution; like in our case, however, their patient's visual field defect was found to be permanent at 18-month follow-up. Cerebral infarction as a result of blood flow disturbance due to the pial angioma in SWS has been described as a possible mechanism for permanent visual field defect.12 However, in the absence of an acute infarct, repeated ischaemic injury due to vasogenic leakage and perfusion impairment might cause neuronal dysfunction adjacent to the angioma leading to permanent loss of function.11

In contrast to our case, the typical presenting symptoms of SWS are facial naevus and epileptic seizures, the latter being present in 83% of patients with SWS.13 Seizures often present in the first year of life as a consequence of the angioma initiating ischaemia, hypoxia and gliosis, which causes cortical irritability.6 In our case, the first seizure manifested at 6 years of age with no further seizures for 3 years despite not being on any treatment. After he had his second seizure aged 9 with confirmed diagnosis of SWS type 3 on neuroimaging, he was started on regular antiepileptic medication as there is a high chance of seizure recurrence.

The neurological outcome in SWS ranges from minimal or no neurological signs to devastating impairment in the form of uncontrolled seizures, visual field defects, hemiparesis and mental retardation. Neurological deficits in the form of transient hemiparesis can be present in 65% of patients,13 and these may be postictal or due to vascular ischaemia.6 An EEG can help to differentiate the cause of neurological deficit as it would be normal in vascular ischaemia, and these cases would benefit from stroke prophylaxis in the form of aspirin.14 15 In our case, the current EEG was non-conclusive as the findings could either be of postictal origin or related to the presence of the angiomatosis lesion. His first EEG 3 years ago, prior to diagnosis, had similar findings of focal slowing with no epileptiform discharges which in hindsight was unlikely to be a result of encephalitis but rather postictal or secondary to vascular ischaemia.

The management of SWS revolves primarily around seizures control, with surgical resection reserved for refractory cases. Ophthalmological follow-up is also important to identify and treat any ocular involvement. Children with recurrent hemiparetic episodes of vascular origin should be started on Aspirin after consultation with a paediatric neurologist. Aspirin prophylaxis helps to reduce vascular phenomenon, thereby improving overall neurological outcome. Bay et al14 conducted internet-based survey on use of aspirin in SWS to access the effectiveness and safety of aspirin treatment. The study showed significant reduction in stroke-like episodes and also the seizure frequency. 39% of the patients reported complications predominantly increased bruising and gum/nose bleed; however, none reported discontinued aspirin because of side effects. A study by Lance et al15 also showed significant support for use of low dose aspirin to optimise neurodevelopmental outcome in SWS.

Other features of SWS include learning difficulties (40–50%);9 of whom, almost all of them suffer with seizures6 and glaucoma (60%).16

MRI brain is the gold standard for diagnosis of SWS. MRI demonstrates abnormal white matter and gadolinium enhancement of leptomeningeal angioma. CT scan in a patient with SWS shows abnormal contrast enhancement of angioma and cortical atrophy with ‘Tram-line’ calcifications characteristic imaging features. CT scan may also show hypertrophy of choroid plexus, but our patient did not have this radiological finding. Neuroimaging findings in our case are typical of SWS.

The prognosis of SWS is varied but one report showed that 58% of patients required special education classes and showed signs of early developmental delay; increasing age of first seizure was associated with a decreasing trend in the rate of delay.16 If a child was without seizures, 6% had developmental delay and 11% required educational support.16 If the onset of seizure is before the age of 2, you are more likely to show developmental delay and drug resistant seizures have a more severe degree of learning difficulty.17

Learning points.

SWS type 3 is a rare and challenging disease and needs a high degree of suspicion; hence, a detailed history and physical examination plus radiological investigation are needed in evaluation of these patients.

Headache in SWS is usually secondary to vascular disease giving symptoms of migraine headache, and the prevalence of migraine in children with SWS is much greater than that in the general population.

The findings of SWS on CT and magnetic resonance include superficial cerebral calcification, hypertrophy of choroid plexus, cerebral atrophy and leptomeningeal enhancement.

Footnotes

Contributors: PRJ and MI performed literature research and wrote the article. MP helped in final drafting the article.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Shirley MD, Tang H, Gallione CJ et al. Sturge-Weber syndrome and port-wine stains caused by somatic mutation in GNAQ. N Engl J Med 2013;368:1971 10.1056/NEJMoa1213507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hobson C, Foyaca-Sibat H, Hobson B et al. Sturge Weber Syndrome type 1 ‘plus’: a case report. Internet J Neurol 2005;5 . [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mammen AC, Murmu SK, Majhi SC et al. Sturge Weber syndrome type III–a rare case report. IOSR J Dent Med Sci 2015;1:23–6. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Knipe H, Gaillard F et al. Sturge-Weber syndrome.rID: 8210 2010. http://radiopaedia.org/articles/sturge-webersyndrome-1 (accessed 13 Apr. 2016).

- 5.IHS—International Headache Society. 2016. http://www.ihs-classification.org/en/

- 6.Sanghvi J, Mehta S, Mulye S et al. Paroxysmal vascular events in Sturge–Weber syndrome: role of aspirin. J Pediatric Neurosci 2014;9:39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rochkind S, Hoffman HJ, Hendrick EB. Sturge-Weber syndrome: natural history and prognosis. J Epilepsy 1990;3(Suppl):293–304. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gomez MR, Bebin EM. Sturge-Weber syndrome. In: Gomez MR, ed.. Neurocutaneous diseases: a practical approach. London: Butterworths, 1987:356–67. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lisotto C, Mainardi F, Maggioni F et al. Headache in Sturge–Weber syndrome: a case report and review of the Literature. Cephalalgia 2004;24:1001–4. 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2004.00784.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prabhakar P, Arkush L, Scott R et al. EHMTI-0310. Headache in children with Sturge-Weber syndrome. J Headache Pain 2014;15(Suppl 1):C52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang HY, Lin KH, Chen JC et al. Type III Sturge-Weber syndrome with migraine-like attacks associated with prolonged visual aura. Headache 2013;53:845–9. 10.1111/head.12067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shimakawa S, Miyamoto R, Tanabe T et al. Prolonged left homonymous hemianopsia associated with migraine-like attacks in a child with Sturge-Weber Syndrome. Brain Dev 2010;32:681–4. 10.1016/j.braindev.2009.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sujansky E, Conradi S. Outcome of Sturge-Weber syndrome in 52 adults. Am J Med Genet 1995;57:35–45. 10.1002/ajmg.1320570110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bay MJ, Kossoff EH, Lehmann CU et al. Survey of aspirin use in Sturge-Weber syndrome. J Child Neurol 2011;26:692–702. 10.1177/0883073810388646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lance EI, Sreenivasan AK, Zabel TA et al. Aspirin use in Sturge-Weber syndrome side effects and clinical outcomes. J Child Neurol 2013;28:213–18. 10.1177/0883073812463607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sujansky E, Conradi S. Sturge-Weber syndrome: age of onset of seizures and glaucoma and the prognosis for affected children. J Child Neurol 1995;10:49–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jagtap S, Srinivas G, Harsha KJ et al. Sturge-Weber syndrome clinical spectrum, disease course, and outcome of 30 patients. J Child Neurol 2013;28:722–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]