Abstract

Here, we report the history of a 42-year-old female patient with sporadic mismatch-repair-deficient metastatic colorectal cancer and abdominal bulky disease, who received pembrolizumab (200 mg every 3 weeks) after the failure of third-line treatment. Restaging 3 months after initiation of treatment revealed a striking response with shrinkage of the bulky peritoneal tumour mass (baseline size 11×11×14 cm) to nearly 25% of the original tumour volume (6.2×7.1×10.4 cm). Restaging 8 months after initiation showed further downsizing of the tumour mass (5.5×7.0×8.0 cm). Tumour markers CEA and CA 19-9 decreased to normal levels, haemoglobin level increased from 8 to 13 mg/dL and her overall clinical performance status increased from ECOG 3 to 1 within 3 months. Therapy with pembrolizumab was continued and is still ongoing. We emphasise the importance of testing for mismatch-repair status in metastatic disease.

Keywords: Mismatch-repair-deficiency, colon cancer, Pembrolizumab, PD-1-blockade, bulky disease

Key questions.

What is already known about this subject?

Immunotherapy with checkpoint inhibitors has proven to yield remarkable responses in a variety of malignancies. It has been shown that in colorectal cancer (CRC), tumours with mismatch-repair-deficiency are especially susceptible to blockade with antibodies targeting PD-1 or PDL-1.

What does this study add?

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of a patient with a very large bulky tumour mass from her relapsing CRC that responded to PD-1-blockade with pembrolizumab after progressing under standard chemotherapy and bad performance status (ECOG 3) at initiation of therapy.

How might this impact on clinical practice?

As there are novel therapeutic options now available for a subset of patients with mCRC , the microsatellite instability status should be assessed at the time of diagnosis. Immunotherapy with checkpoint inhibition might also be a therapeutic option in mCRC patients with bad performance status, not capable of receiving standard chemotherapy.

Background

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the second most frequent cancer diagnosed in Europe with an incidence about 447 000 new cases per year. Approximately 25% of patients present with metastases at the time of initial diagnosis and nearly 50% of patients will develop metastases, contributing to the high mortality rates reported for CRC.1 The CRC-5-years survival rate in Austria is about 65%.2

According to the ESMO Guidelines, the current standard for the treatment of mCRC is a cytotoxic doublet, consisting of a fluoropyrimidine plus oxaliplatin plus irinotecan, in combination with a monoclonal antibody against VEGF or EGFR (in RAS wild-type tumours).3

While in second line, the chemotherapy is switched and can be combined with monoclonal antibodies, in the salvage setting, regorafenib, a multikinase inhibitor, has shown efficacy in patients and is approved in Europe since 2013.4 The drug combination of trifluridine/tipiracil has received a positive opinion by the European Medicines Agency and prolongs the survival of pretreated patients with mCRC as shown in a recent global phase III study and might be another therapeutic option for pretreated patients.5

With all these treatment options, the median overall survival of patients with mCRC or non-resectable disease is between 28.76 and 37.1 months7 (FIRE 3, TRIBE).

Mismatch-repair-deficient CRC represents ∼10–20% of all patients with CRC and only 3–6% of patients with advanced CRC.8 9 In CRC, microsatellite instability (MSI), which refers to mutations in a tract of tandemly repeated DNA motifs (microsatellites), is typically caused by epigenetic silencing or mutation of DNA mismatch repair genes. The suggested approach to evaluate MSI is via PCR of five DNA markers or immunohistochemical analysis of DNA mismatch repair enzymes. Immunostaining of the mismatch repair enzymes MLH1, MSH2, MSH6 and PMS2 is equivalent in levels of sensitivity and specificity to MSI analysis via PCR.10 In our centre, a two-step approach is performed. If the immunohistochemistry is negative for one of the above-mentioned mismatch repair enzymes, the suspected MSI is confirmed via PCR.

The microenvironment of microsatellite instable colon cancer displays high infiltration with activated CD8+ CTL as well as activated Th1 cells. It has been shown that MSI tumours counterbalance this active Th1/CTL microenvironment by expression of multiple immune checkpoints such as programmed death 1 (PD-1). The binding of PD-L1 or PD-L2 to PD-1 results in inhibition of T-cell immune functions and can constitute a form of immune escape mechanism.

In contrast to other tumours such as melanoma, renal or lung cancer, where PD-L1 is expressed by tumour cells, in MSI CRC PD-L1 is expressed predominantly by infiltrating myeloid cells.11

Advances in immunotherapy, especially blocking the negative feedback pathway of PD-1 with monoclonal antibodies, have shown remarkable clinical responses in patients with different types of cancers such as melanoma, non-small-cell-lung cancer, renal cell cancer, bladder cancer and Hodgkin's lymphoma.12–17 In May 2015, Le et al18 demonstrated the clinical activity of pembrolizumab, a humanised monoclonal anti PD-1 antibody of the IgG4 κ isotype blocking the interaction between PD-1 and its ligands, PD-L1 and PD-L2, on treatment-refractory progressive mCRC with mismatch-repair deficiency. In this study, a small group of patients (n=10) with mismatch-repair-deficient CRC had a partial response in 40% and a stable disease at week 12 in 50%. In contrast, patients with mismatch-repair-proficient tumours did not respond to immunotherapy and pembrolizumab was almost ineffective. These stimulating results suggest a new therapeutic option in a carefully selected subset of patients with mCRC.

Case report

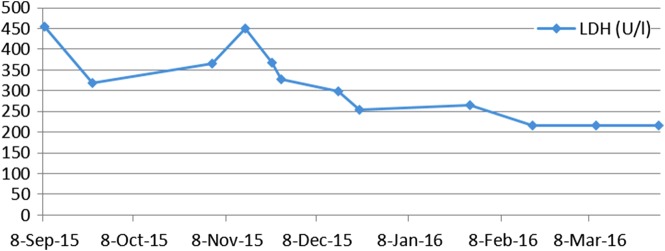

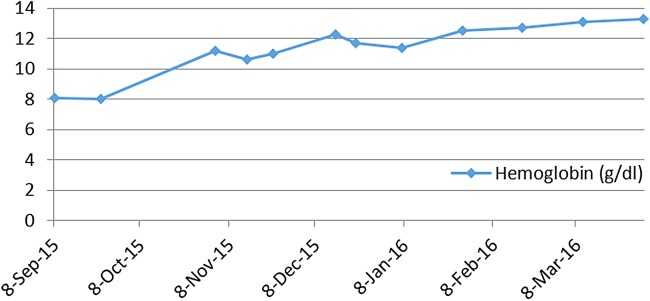

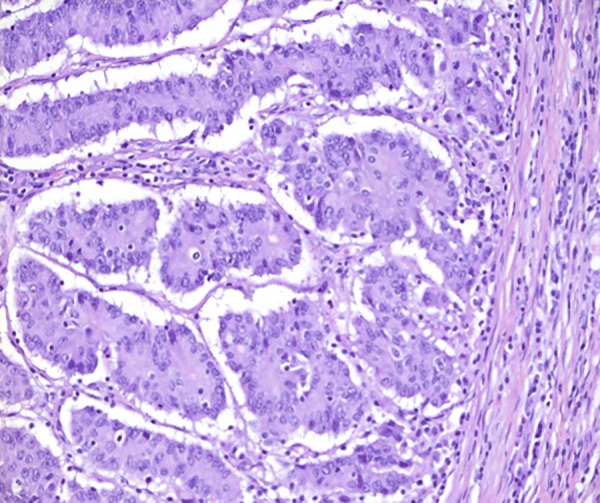

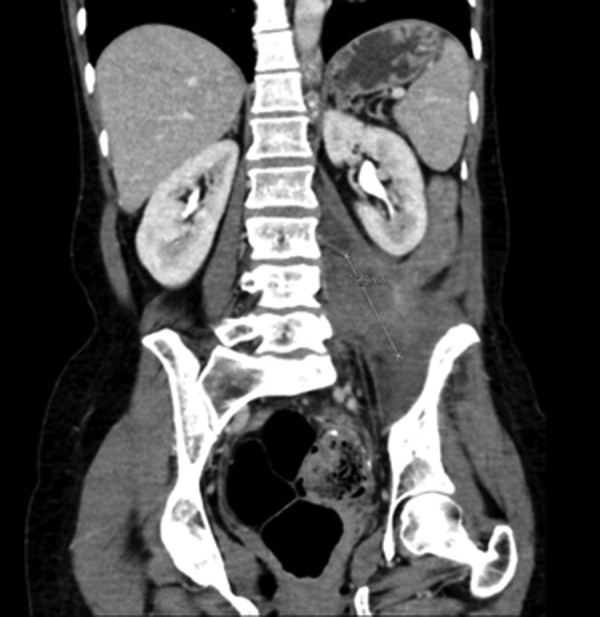

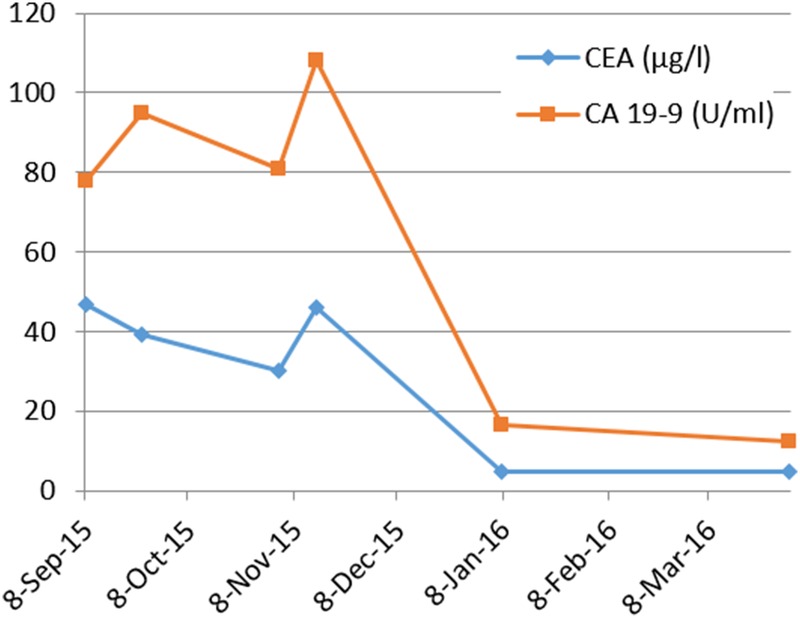

Here, we report the history of a 42-year-old woman, who was diagnosed with stage III KRAS mutant (G13D) CRC in 2013, when she underwent an emergency sigma resection due to perforation. She received adjuvant treatment with eight cycles of XELOX until January 2014. In December 2014, peritoneal metastases were detected and her overall physical status decreased steadily over time. Only five cycles of FOLFIRI were administered until September 2015. Suspected disease progression was confirmed when she was restaged, showing a large unresectable bulky peritoneal metastasis with about 11×11×14 cm holding in size (baseline size 11×11×14 cm, see figures 1 and 2). When she was referred to our department in September 2015, she was incapable to walk with a reduced performance status of ECOG 3. A molecular profile of the tumour revealed mismatch-repair deficiency of MLH1/PMS2 in the tumour DNA, but not in the germline DNA. In retrospect, the tumour showed a characteristic histological picture of a high number of tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes (see figure 3). Hence, therapy with pembrolizumab (200 mg every 3 weeks) was initiated in the end of September 2015. After three cycles, a restaging was performed. No new metastases were diagnosed and compared to the last scan she had a stable disease mass. After these very promising results, the treatment with pembrolizumab for another three cycles were continued. At the end of December, a CT scan showed an impressive response with shrinkage of the peritoneal tumour mass to 25% of the original tumour volume (6.2×7.1×10.4 cm, see figures 4 and 5). Tumour markers CEA and CA 19-9 and LDH levels decreased to normal levels, haemoglobin level increased from 8 to 13 mg/dL and her overall clinical performance status increased from ECOG 3 to 1 within 3 months (see figures 6–8). Restaging after 11 cycles of pembrolizumab showed further downsizing of the tumour mass (5.5×7.0×8.0 cm, see figures 9 and 10). The therapy with pembrolizumab is still ongoing.

Figure 1.

Axial baseline CT scan: large bulky peritoneal tumor mass with about 11×11×14 cm holding in size.

Figure 2.

Coronal baseline CT scan: large bulky peritoneal tumor mass with about 11×11×14 cm holding in size.

Figure 3.

Invasion front (pushing margin) of the patient's tumour from the primary resection showing a high number of tumour-infiltrating leucocytes, which is characteristic for mismatch-repair-deficient (MMR) tumours.

Figure 4.

Axial CT scan after six cycles of pembrolizumab shows a partial remission of the peritoneal tumour mass to 25% of the original tumour volume (6.2×7.1×10.4 cm).

Figure 5.

Coronal CT scan after six cycles of pembrolizumab shows a partial remission of the peritoneal tumour mass to 25% of the original tumour volume (6.2×7.1×10.4 cm).

Figure 6.

Axial CT scan after 11 cycles of pembrolizumab shows a further regression of the tumour mass to 5.5×7.0×8.0 cm.

Figure 7.

Coronal CT scan after 11 cycles of pembrolizumab shows a further regression of the tumour mass to 5.5×7.0×8.0 cm.

Figure 8.

Kinetics of serum tumor marker concentrations CEA and CA 19-9: from initiation of therapy in September 2015 to completion of 11 cycles pembrolizumab in late March 2016.

Figure 9.

Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) kinetics: from initiation of therapy in September 2015 to completion of 11 cycles pembrolizumab in late of March 2016.

Figure 10.

Steady rise in hemoglobin concentration: from initiation of therapy in September 2015 to completion of 11 cycles pembrolizumab in late of March 2016.

Discussion

While it has been proven that immunotherapy with checkpoint inhibitors may be a potent new therapeutic option in certain malignancies such as metastatic melanoma, so far in only a small sample size of patients with mCRC pembrolizumab had been tested. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of a sporadic MSI tumour, which responded after the failure of oxaliplatin, irinotecan and fluoropyrimidine, leading to a substantial response for at least 8 months and is ongoing. As demonstrated in previous publications and as we have also shown here, immunotherapy can yield remarkable responses in the subset of mismatch-repair-deficient colon cancer. For this reason, we emphasise the importance of testing for mismatch-repair status in metastatic disease.

Footnotes

Contributors: MK was involved in summarising clinical data and writing manuscript. WS was involved in writing manuscript, reviewing manuscript, clinical assessment and experimental patient treatment. CZ was involved in reviewing manuscript. AC was involved in immunohistochemical analysis and provided figure 3. AA-M was involved in reviewing manuscript and radiological assessment and provided figures 1, 2, and 4–9. GP was involved in writing manuscript, reviewing manuscript, clinical assessment and experimental patient treatment.

Funding: Initiative Krebsforschuung (UE 71104027).

Competing interests: CZ has reported honoraria (Advisory Boards) from Bristol Myers, Squibb, Imugene, Roche, Baxalta, AbbVie and Novartis.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: Ethik Kommission—Medizinische Universität Wien.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Ferlay J, Steliarova-Foucher E, Lortet-Tieulent J et al. . Cancer incidence and mortality patterns in Europe: estimates for 40 countries in 2012. Eur J Cancer 2013;49:1374–403. 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.12.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haidinger G, Waldhoer T, Hackl M et al. . Survival of patients with colorectal cancer in Austria by sex, age, and stage. Wien Med Wochenschr 2006;156:549–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Van Cutsem E, Cervantes A, Nordlinger B et al. . The ESMO Guidelines Working Group. Metastatic colorectal cancer: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 2014;25:iii1–9. 10.1093/annonc/mdu260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grothey A, Van Cutsem E, Sobrero A et al. . Regorafenib monotherapy for previously treated metastatic colorectal cancer (CORRECT): an international, multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2013;381:303–12. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61900-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mayer RJ, Van Cutsem E, Falcone A et al. . Randomized trial of TAS-102 for refractory metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med 2015;372:1909–19. 10.1056/NEJMoa1414325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heinemann V, von Weikersthal LF, Decker T et al. . FOLFIRI plus cetuximab versus FOLFIRI plus bevacizumab as first-line treatment for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer (FIRE-3): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2014;15:1065–75. 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70330-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cremolini C, Loupakis F, Antoniotti C et al. . FOLFOXIRI plus bevacizumab versus FOLFIRI plus bevacizumab as first-line treatment of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer: updated overall survival and molecular subgroup analyses of the open-label, phase 3 TRIBE study. Lancet Oncol 2015;16:1306–15. 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00122-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goldstein J, Tran B, Ensor J et al. . Multicenter retrospective analysis of metastatic colorectal cancer (CRC) with high-level microsatellite instability (MSI-H). Ann Oncol 2014;25:1032–8. 10.1093/annonc/mdu100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koopman M, Kortman GAM, Mekenkamp L et al. . Deficient mismatch repair system in patients with sporadic advanced colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer 2009;100:266–73. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boland CR, Goel A. Microsatellite instability in colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterology 2010;138:2073–2087.e3. 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.12.064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Llosa NJ, Cruise M, Tam A et al. . The vigorous immune microenvironment of microsatellite instable colon cancer is balanced by multiple counter-inhibitory checkpoints. Cancer Discov 2015;5:43–51. 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-14-0863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ansell SM, Lesokhin AM, Borrello I et al. . PD-1 blockade with nivolumab in relapsed or refractory Hodgkin's lymphoma. N Engl J Med 2015;372:311–19. 10.1056/NEJMoa1411087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hamid O, Robert C, Daud A et al. . Safety and tumor responses with lambrolizumab (anti-PD-1) in melanoma. N Engl J Med 2013;369:134–44. 10.1056/NEJMoa1305133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Herbst RS, Soria JC, Kowanetz M et al. . Predictive correlates of response to the anti-PD-L1 antibody MPDL3280A in cancer patients. Nature 2014;515:563–7. 10.1038/nature14011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Powles T, Eder JP, Fine GD et al. . MPDL3280A (anti-PD-L1) treatment leads to clinical activity in metastatic bladder cancer. Nature 2014;515:558–62. 10.1038/nature13904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McDermott DF, Drake CG, Sznol M et al. . Survival, durable response, and long-term safety in patients with previously treated advanced renal cell carcinoma receiving nivolumab. J Clin Oncol 2015;33:2013–20. 10.1200/JCO.2014.58.1041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Topalian SL, Hodi FS, Brahmer JR et al. . Safety, activity, and immune correlates of anti-PD-1 antibody in cancer. N Engl J Med 2012;366:2443–54. 10.1056/NEJMoa1200690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Le DT, Uram JN, Wang H et al. . PD-1 blockade in tumors with mismatch-repair deficiency. N Engl J Med 2015;372:2509–20. 10.1056/NEJMoa1500596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]