Abstract

Being aware of controversies and lack of evidence in peritoneal dialysis (PD) training, the Nursing Liaison Committee of the International Society for Peritoneal Dialysis (ISPD) has undertaken a review of PD training programs around the world in order to develop a syllabus for PD training. This syllabus has been developed to help PD nurses train patients and caregivers based on a consensus of training program reviews, utilizing current theories and principles of adult education. It is designed as a 5-day program of about 3 hours per day, but both duration and content may be adjusted based on the learner. After completion of our proposed PD training syllabus, the PD nurse will have provided education to a patient and/or caregiver such that the patient/caregiver has the required knowledge, skills and abilities to perform PD at home safely and effectively. The course may also be modified to move some topics to additional training times in the early weeks after the initial sessions. Extra time may be needed to introduce other concepts, such as the renal diet or healthy lifestyle, or to arrange meetings with other healthcare professionals. The syllabus includes a checklist for PD patient assessment and another for PD training. Further research will be needed to evaluate the effect of training using this syllabus, based on patient and nurse satisfaction as well as on infection rates and longevity of PD as a treatment.

Keywords: Peritoneal dialysis, nursing, patient education, training, teaching, curriculum, adult learner

In 2006, the International Society for Peritoneal Dialysis (ISPD) Nursing Liaison Committee published the ISPD Guidelines/Recommendations for peritoneal dialysis (PD) patient training, aiming to help PD nurses prepare patients and/or their caregivers to perform PD (1). Based on the principles of adult learning, these guidelines established a broad description of a course and a set of proposals to aid the teacher/nurse (hereafter called the PD nurse). The committee currently believes that, while the recommendations are still relevant and agree with current teaching practices in PD clinics, there is a need for a more comprehensive course to guide PD nurses.

The 2006 Guidelines tried to answer some questions that arise when talking about PD training: Who should be the trainer? Who is the learner? What should be taught? Where should the training occur? What should be the duration of training? How should the patient be taught? However, many of these questions remain unanswered. A search in PubMed using the words “training,” “patient education,” “peritoneal dialysis,” and “peritonitis” found only 17 articles published in the last 5 years, and most of these were about infection prevention. Only 4 were published in the last 12 months. Of these 1 article was a narrative review of the literature of educational interventions in PD which concluded that the topic remained an under-studied aspect of PD (2); another looked at the impact of training hours on infection and suggested a minimum of 15 hours training, to be done before catheter implantation or more than 10 days after (3), and the remaining 2 looked at preventing PD infections (4,5). One further observational study, by Firanek et al., analyzing best practices for nurse-led PD training programs for patients on automated peritoneal dialysis (APD) in the United States, stated that best practices included: using simple training instructions with a “hands-on” approach; incorporating principles of adult learning into the teaching methodologies; and extending the training time as necessary for individual patients with, for example, dexterity issues, problems with physical symptoms, or concentration issues. After completion of PD training, PD nurses performed a home visit for the first at-home treatment or scheduled a phone call for this time. Thereafter, home visits were made yearly. They also provided patients with 24-hour telephone support (6).

As educators, we must continually re-think and re-evaluate our education practices, particularly with adult learners. While there is still much we do not know about how our minds work and how people best learn, we do know a great deal that we can apply to our teaching to improve the outcomes of our learners (7).

Aware of controversies and lack of evidence in PD training, the ISPD Nursing Liaison Committee has undertaken a review of PD training programs around the world in order to develop a syllabus for optimal training. We understand the variety of backgrounds and particularities that exist and we do not intend to determine what should or should not be done, but rather to propose a comprehensive guide based on expert experience and research. The Committee now presents a specific syllabus to more clearly guide the PD nurse through the process of assisting and guiding a patient and/or caregiver who is naïve to the therapy through the process of learning the skills and concepts to safely perform independent PD.

Survey of PD Programs Around the World

In order to examine current practices, a survey was conducted of a convenience sample of PD training courses used by PD centers around the world. Fourteen courses from 10 countries were reviewed: Australia, Brazil, Canada, China, Guatemala, Japan, Mexico, New Zealand, United Kingdom, and the United States. The course descriptions ranged from 1 to 10 pages, with 13 of the 14 simply listing topics to be covered. Only 1 course had detailed descriptions of each topic with related objectives. Course duration (total or per diem) was not indicated in 11 of the 14 courses. Three courses designated duration of training: 3 hours per day for 10 days (30 hours total), 2.5 hours per day for 4 days (10 hours total), and 15 hours over a 5-day period. None of the courses referred to how to teach or how to assess adult learning.

Based on the divergence of current course materials reviewed by the Committee, there is a clear need for a specific syllabus to be developed. The following syllabus (Appendix A), assessment, and follow-up (Appendices B and C) are presented as a model for nurses teaching in PD units, based upon principles of adult learning and teaching. The syllabus can be applied as presented here or modified and adapted to meet local needs, customs, and cultures. The previously published guidelines (1) provide a foundation for this syllabus.

It is understood that training is only one aspect of a successful PD program. Other aspects to consider are the experience of the PD nurses and nephrologists, catheter implantation technique, and environmental barriers that may impact the outcomes (8–10). Therefore, the objective of this syllabus is to assist PD nurses to train their patients based on a consensus of training program reviews, utilizing current theories and principles of adult education.

ISPD Syllabus for Teaching Patients and/or Caregivers Home PD

Description of Course

This course offers day-by-day descriptions of topics to be covered and suggests methods of teaching and learning for a home PD program. Based on the concept that adults learn differently than children (11), which is especially true for health education (12), it is designed to guide the PD nurse to organize the topics according to the learner's needs, adhering to principles of adult learning. Knowles (11) presented 6 principles for adult education: adults are internally motivated and self-directed; adults bring life experiences and knowledge to learning experiences; adults are goal-oriented; adults are relevancy-oriented; adults are practical; and adult learners like to be respected. Included in the course are tips from education experts to enhance learning and methods of testing the learner throughout the course. Adult educator, J.T. Bruer noted, “Learning is the process by which novices become experts.” Our goal is therefore to assist our patients to become experts in their own PD care (13).

At the end of the course, the nurse will have taught a patient and/or caregiver to safely, comfortably, and effectively understand the concepts of, and perform the required skills for, PD at home. The course will also provide a foundation for ongoing learning and problem solving for self-management of home PD. Establishing a rapport with the patient and assessing learning styles and possible barriers for learning are new topics to be covered beyond the previous list in the 2006 Guideline/Recommendation (1).

Training may take place in a PD clinic, in the patient's home, in the hospital, or any suitable location equipped for focused PD teaching. There have been no randomized trials to determine which site is superior. Basic requirements are the same as previously stated (1). Combining visual and audio aids promotes learning, and these may be used depending upon the learner's preferred learning style. Written handouts, pictures (especially for the low literacy learner), videos, and computer-assisted learning may be incorporated as appropriate. The teaching environment should be made physically and psychologically comfortable.

Assessment of Patient's Preferred Learning Style

Learning styles describe the way people interact with learning conditions and include cognitive, affective, physical, and environmental aspects, which can support information processing. There are several instruments that can help the nurse assess a patient or family member's preferred learning styles (11), and it is important to know that no learning style is better than another (14).

There are a variety of learning models. Fleming and Mills's (15) VARK learning styles questionnaire is very simple and useful for patient teaching. VARK stands for Visual, Aural (or Auditory), Read and write, and Kinesthetic (or Motor) modality of learning. This questionnaire uses simple questions that can be easily understood by patients, such as: You are about to purchase a digital camera or mobile phone. Other than price, what would most influence your decision? Trying or testing it; the salesperson telling me about its features; reading the details or checking its features online; or, it is a modern design and looks good.

Another common instrument used is Kolb's learning style inventory, which describes 4 different abilities: concrete experience, reflective observation, abstract conceptualization, and active experimentation abilities. The combination of these 4 abilities will represent the 4 styles: Converger (abstract conceptualization + active experimentation); Diverger (concrete experience + reflective observation); Assimilator (abstract conceptualization + reflective observation); and Accommodator (concrete experience + active experimentation) (16).

It does not matter which instrument is used, but once the preferred learning style is identified, the nurse should plan the education accordingly.

Learning Plans and Evaluation

The course preferably should be taught one-on-one, nurse-to-patient, whenever possible, and for consistency, ideally should be taught by the same nurse throughout the training. The nurse is expected to give undivided attention to the learner at each training session; respect the learner's individual preferred learning style, and be aware of his or her own preferred style of learning.

The PD nurse will demonstrate and supervise all procedure practice in order to give immediate feedback to the patient/learner throughout the course. The nurse will also provide formative evaluation that allows ongoing assessment of the learning achieved and readjustment of the syllabus. The nurse will periodically check the progress of the patient/learner by asking questions that require the learner to recognize problems and concepts and select appropriate responses.

The pace of learning and achievement of goals will be openly shared with the learner. The nurse will recognize that a patient with chronic renal failure, unlike healthy adult learners who choose what to learn, will rely on the nurse's help to establish aspects to be learned and all the necessary procedures and concepts for home PD self-care (17).

Procedural skills will be taught in a manner appropriate to the preferred learning style of the learner. One suggested way to do this is based on a publication by George and Doto (18) called “A simple five-step method for teaching clinical skills,” in which the teacher performs the entire procedure, start to finish, without talking, then repeats with the learner reading the steps aloud as the teacher performs (6,18). This is repeated until the learner knows the steps in the proper order (cognitive learning). Practice then begins with use of the practice catheter (mannequins), with the learner reading each step aloud before performing (this programs the brain to perform the task). The nurse supervises all practice to provide immediate feedback and encouragement. Supervised practice is repeated at spaced intervals until the learner can perform without errors at least 3 times (autonomic response—brain recognizes errors). Careful consideration must be given to the learner's progress, as not everyone learns at the same speed or in the same manner. Understanding the learning style of each patient/learner will help the nurse to set the best way to teach the procedure.

At the end of the training, the patient will be tested on the skills for all PD exchange procedures, in addition to undergoing a summative evaluation assessing the impact of the intervention. The minimum objectives to be met are the following.

The patient and/or caregiver:

is able to safely perform PD procedures using aseptic technique for connection;

recognizes contamination and verbalizes appropriate action;

identifies modification of fluid balance and its relationship to hypertension/hypotension;

can detect, report, and manage potential dialysis complications using available resources;

understands when and how to communicate with the home dialysis unit.

The decision of whether to administer an oral and/or written test to determine whether the training objectives have been met is left up to each program.

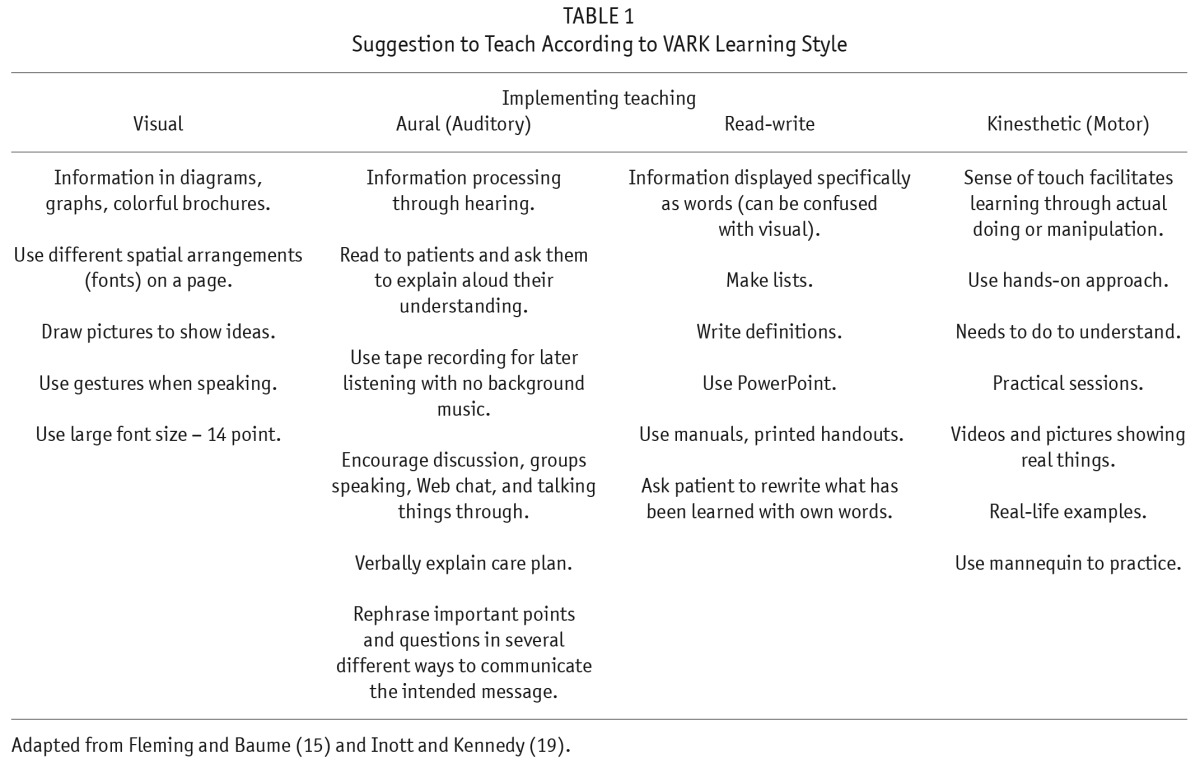

A number of authors have suggestions for implementing patient education, and Table 1 shows some tips for teaching according to the styles identified (14,15,19,20). For all types of learning, it is best to avoid long lectures, interminable sitting, unsupervised practice, and lack of rest periods. The role of humor should not be underestimated. Sometimes PD nurses may be confronted with a challenging patient, or a patient with limited concentration abilities. An alternative for such cases can be to change trainers, as empathy can play an important role during the educational process. Another solution is to try a multisensory approach, using photographs of the bag-exchange procedure or the provision of simple, step-by-step instructions on audiotape (21). A study on the prevalence of cognitive impairment (CI) in PD patients using Montreal Cognitive Assessment found that CI was not a significant independent risk factor for PD-related peritonitis among self-care PD patients with adequate training (22).

TABLE 1.

Suggestion to Teach According to VARK Learning Style

Expectations for Learners

The patient and/or caregiver are expected to attend each training session as scheduled; there are some indications that a patient's poor attendance at training sessions is associated with lower compliance (23).

Schedule

There is no evidence on how the training schedule should be best organized. However, we suggest that training sessions should be held on consecutive days whenever possible to facilitate immersion course learning. Every attempt will be made to limit interruptions to no more than 2 days, at which time training will resume. One study suggests that a training schedule of 1 to 2 hours per session reduces peritonitis rates when compared with training of less than 1 hour per session (3), while a survey conducted in the US found that training times varied considerably in days and hours per day (6). An international survey found that 5 days is the average number of days for training, but it is not known whether training 5 days per week for 4 or more hours per day is more effective than 10 days of training for 2 or more hours per day (24). It is recommended that PD nurses track the number of hours taught each day and record the total teaching hours, as well as the total teaching days, on the checklist (Appendix B). Clinics may examine relationships between duration and patterns of initial PD training with outcomes such as peritonitis rates and exit-site infection rates. These audit measures may guide future plans for the most effective teaching patterns.

Training may be held before or after PD catheter implantation, in part or in whole. A large cohort study has shown that the highest peritonitis rates were associated with training conducted within the first 10 days after PD catheter insertion, and higher benefit was shown when training was carried out either before insertion or 10 days after insertion (3). This reinforces the findings of a previous survey where one-third of all South American and Hong Kong patients were trained before catheter placement, and the remaining were trained after or a combination of before and after catheter placement (24). Careful attention should be given to these issues as a study by Barone et al. (25), comparing 3 different training schedules, suggested that more frequent retraining should be considered in patients who needed more training sessions at the start of PD. These authors surmised that this may be due to impaired learning secondary to uremia, interference from post-operative pain medications, or low literacy level.

For each training day, breaks will be scheduled according to the learning pace of individual patients, but never less frequently than every 2 hours. Some adult educators recommend that lessons should be no more than 30 minutes in length, with no more than 3 to 4 new messages per hour, but there are no data regarding PD patient education (8,26). Ideally, the nurse will introduce a series of procedures and concepts, alternating demonstrations with discussions and questions. The practice of skills and procedures will begin only after the patient has learned the steps of each (cognitive learning). Cognitive learning is defined as “acquisition of problem-solving abilities with intelligence and conscious thought” (8,26). At the beginning of each day, topics will be reviewed from previous sessions to help move new information from short-term memory to storage in long-term memory. The nurse and learner together may use the checklist (Appendix C) at the end of the syllabus to review the course plan for each day and to review learning at the end of each day. Learning topics will be classified by the nurse as: Mandatory – must be learned for survival; Desirable – not life dependent but related to the overall ability to have quality care; and Possible – important information.

Learning requires repetition: an approach that involves “learning by doing” through practice, rehearsal, and role playing, and gives the opportunity to become accustomed to the therapy/procedure (27). The order in which the nurse presents each topic may vary according to individual patient needs; however, the principles of moving from the simple to the complex and from less responsibility to more will be applied. Supervised practice in a safe environment with regular feedback (1-word cues and prompts) promotes learning. Spaced practice with rest intervals increases acquisition and retention. Simple tasks such as hand hygiene, masking (optional), and gathering supplies may have rest intervals of a minute or less. Complex tasks (PD exchange, sterile connection, exit-site care) and complex concepts (asepsis, peritonitis, fluid balance, etc.) require longer spacing intervals, but the optimum interval is unknown. Continuous practice without rest is less effective than practice at spaced intervals (28).

Literacy originally meant a person could read and write his or her name. Today, literacy means the person is able to learn new skills, think critically, and problem solve; it also includes numeracy, or the ability to read and interpret numbers (29). Health literacy is the capacity to obtain and understand basic health information needed to make appropriate health decisions (25,29), and one way to asses it is using the Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine (REALM) questionnaire (30). Strategies to improve health literacy are similar to overall literacy: use plain language and employ the “teach-back” method, in which the learner repeats what has been heard (21). When sick, even those who are literate prefer easy-to-read materials (31).

Some PD units may incorporate content learning and skills such as exit-site care into a pre-course period or spend a day establishing a rapport with the patient (prior to the scheduled training period) and will need to adjust the course content accordingly. This syllabus is designed as a 5-day program of about 3-hours per day, but both duration and content may be adjusted based on the learner. A learner may require more consecutive days of initial training to allow for added supervised practice and in order to master independent skills. The course may also be modified to adjust for frailty, low health literacy, and assisted PD patients by removing, moving and/or adding topics during additional training time. Additional time may be needed to introduce other concepts such as the renal diet or a healthy lifestyle, to arrange meetings with other healthcare professionals, or to continue teaching about topics which were not mandatory but “desirable” and “possible” and were not acquired during the initial training sessions. Two other important points to be addressed are home visits and retraining. While not within the scope of this article, they should be taken into consideration when planning discharge from training. The best timing and frequency for home visits and retraining has not been established (32,33).

Safety and Communication

Patient safety in home dialysis therapies poses special challenges. Peters (34) emphasized the importance of the patient understanding the need for prompt communication with his or her home dialysis unit when a problem is encountered and stressed the need for patients to receive clear guidelines on when, what, and with whom to communicate. Apart from the traditional telephone call, there are newer methods of communication, including telehealth, texting, and e-mail (35–38). Moreover, home dialysis patients today may have access to their own electronic personal health records (39) and, thus, potentially have more involvement in their own care. These newer technologies can be used for guidance and troubleshooting, allowing, for example, a PD patient who lives far away from the unit to attach a photo of a questionable PD catheter exit site or a suspiciously cloudy PD drain bag to an e-mail or text message so that these photos can be reviewed by the PD nurse and nephrologist and a plan for treatment made, avoiding unnecessary travel for the patient (40). Communication is vital for the safety and general wellbeing of PD patients. To further ensure patient safety, a retraining program is needed (7); however, there is no evidence on the optimum timing or frequency of retraining, or for which situations it should be targeted. Meanwhile, the previous guidelines' recommendations should be maintained (that is, retraining after peritonitis, catheter infection, prolonged hospitalization, or any other interruption in PD) (1).

Future Directions

This syllabus is intended as a tool to help PD nurses enhance learning by patients/caregivers so that they can become independent with PD and perform it safely at home. Further research is required to evaluate the effect of training using this syllabus, based on the patients' and nurses' satisfaction as well as on infection rates and longevity of PD as a treatment.

Disclosures

Judith Bernardini is a consultant for Baxter Healthcare; Ana E. Figueiredo received consulting fees and speaker honoraria from Baxter Healthcare; Rachael Walker has a Baxter Healthcare Research Grant.

Acknowledgments

A special thanks to the nurses from the ISPD Nursing Liaison Committee, who provided information about their training programs

Appendix A

Peritoneal Dialysis (PD) Training Course Syllabus

This course is based on Knowles's (11) 6 principles for adult education: 1) adults are internally motivated and self-directed; 2) adults bring life experiences and knowledge to learning experiences; 3) adults are goal-oriented; 4) adults are relevancy-oriented; 5) adults are practical; and 6) adult learners like to be respected.

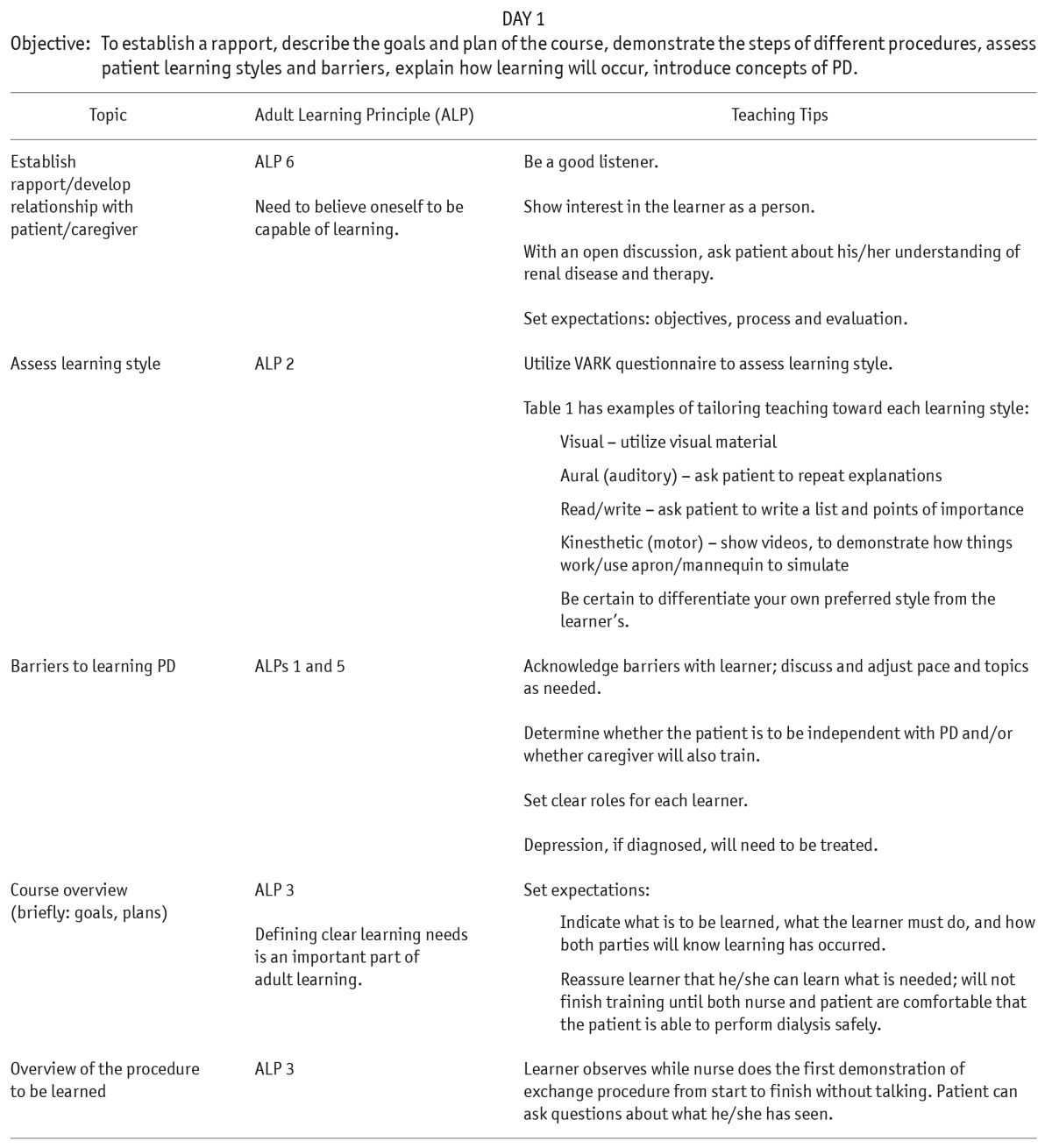

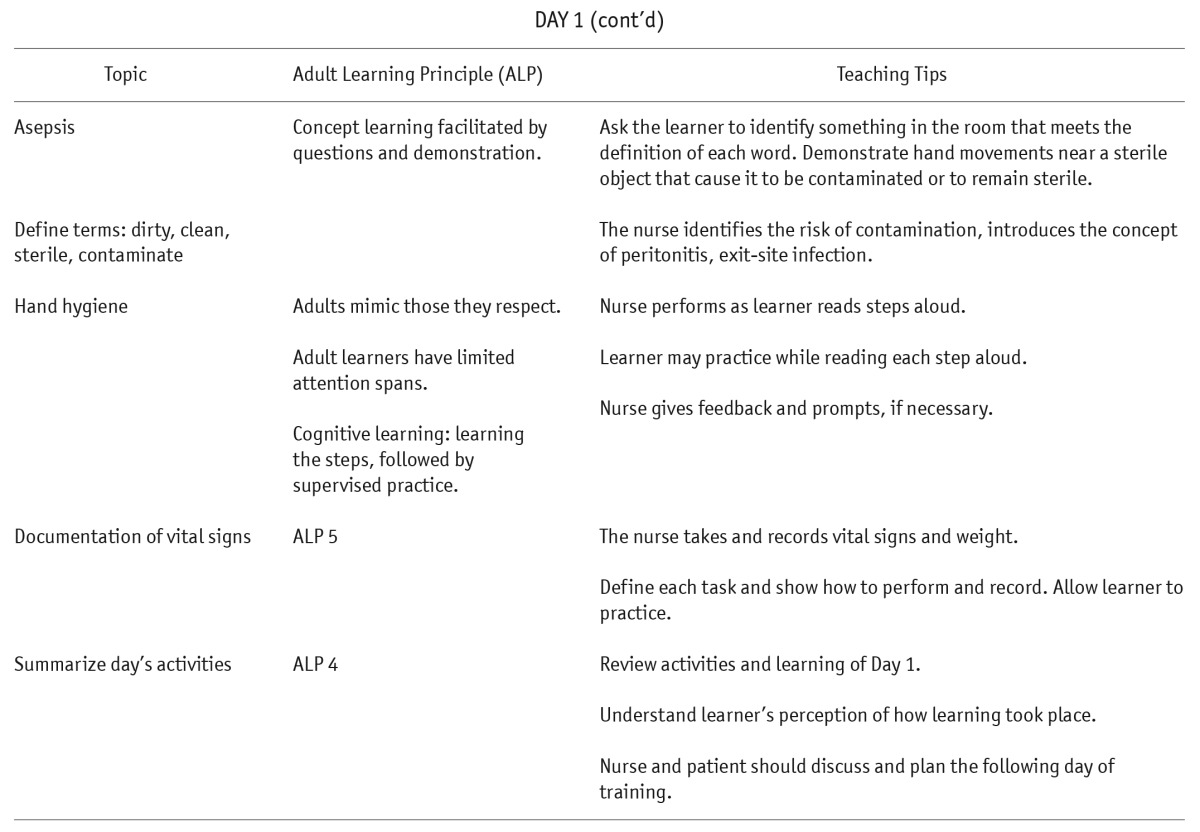

DAY 1

Objective: To establish a rapport, describe the goals and plan of the course, demonstrate the steps of different procedures, assess patient learning styles and barriers, explain how learning will occur, introduce concepts of PD.

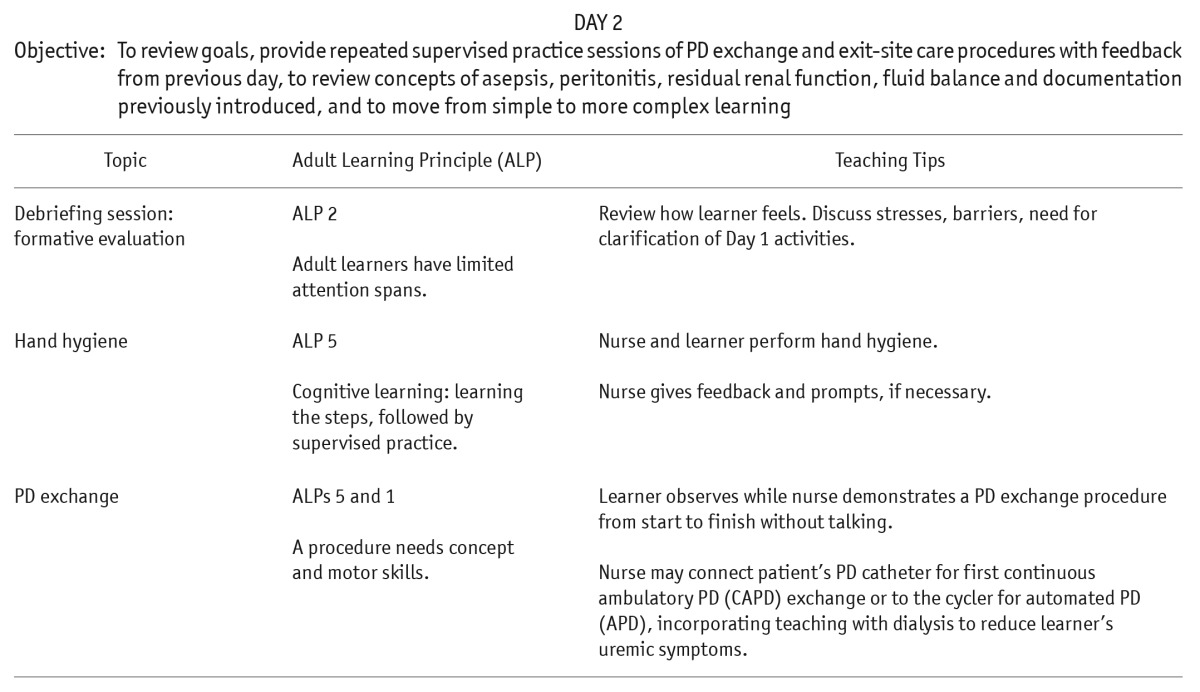

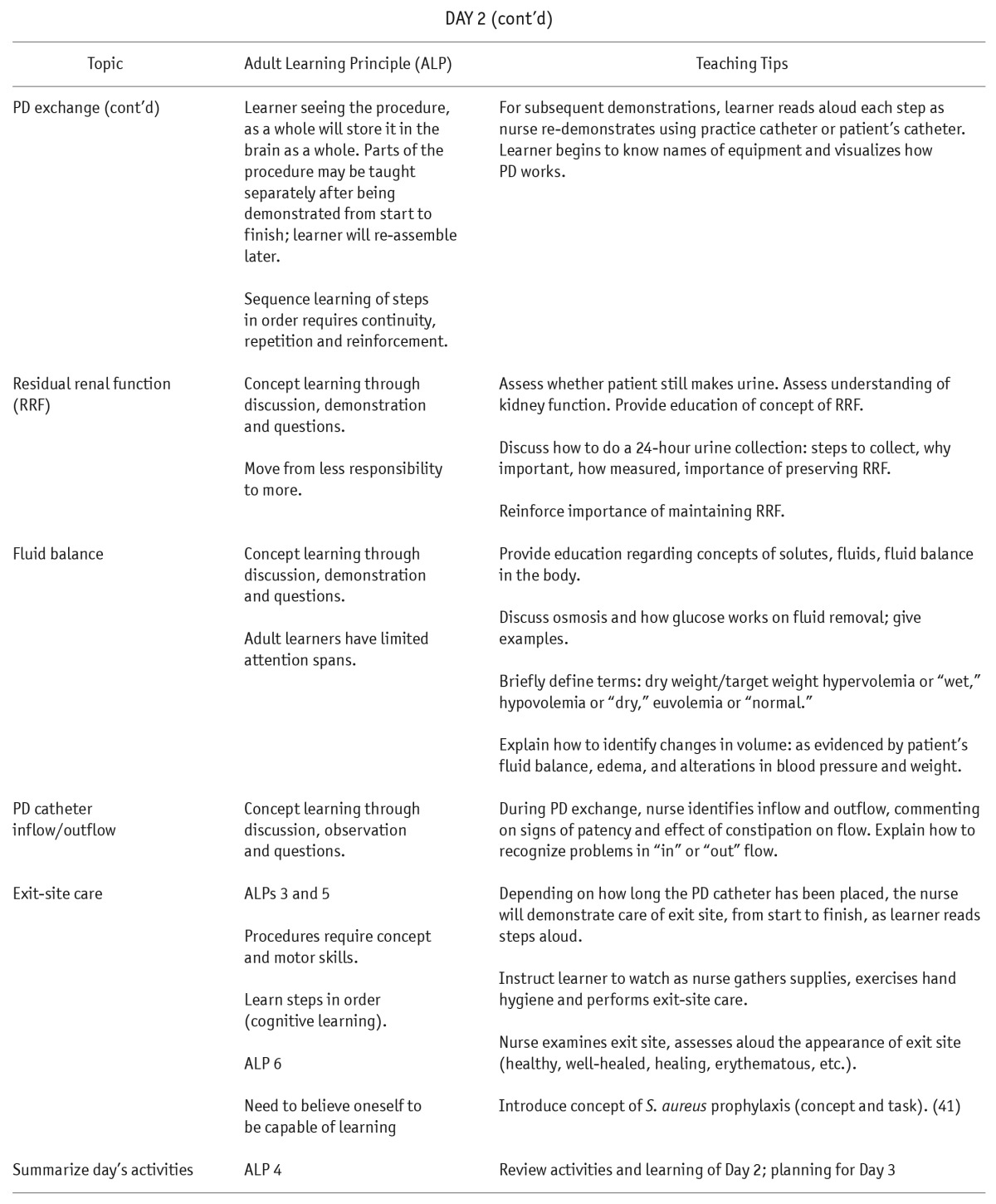

DAY 2

Objective: To review goals, provide repeated supervised practice sessions of PD exchange and exit-site care procedures with feedback from previous day, to review concepts of asepsis, peritonitis, residual renal function, fluid balance and documentation previously introduced, and to move from simple to more complex learning

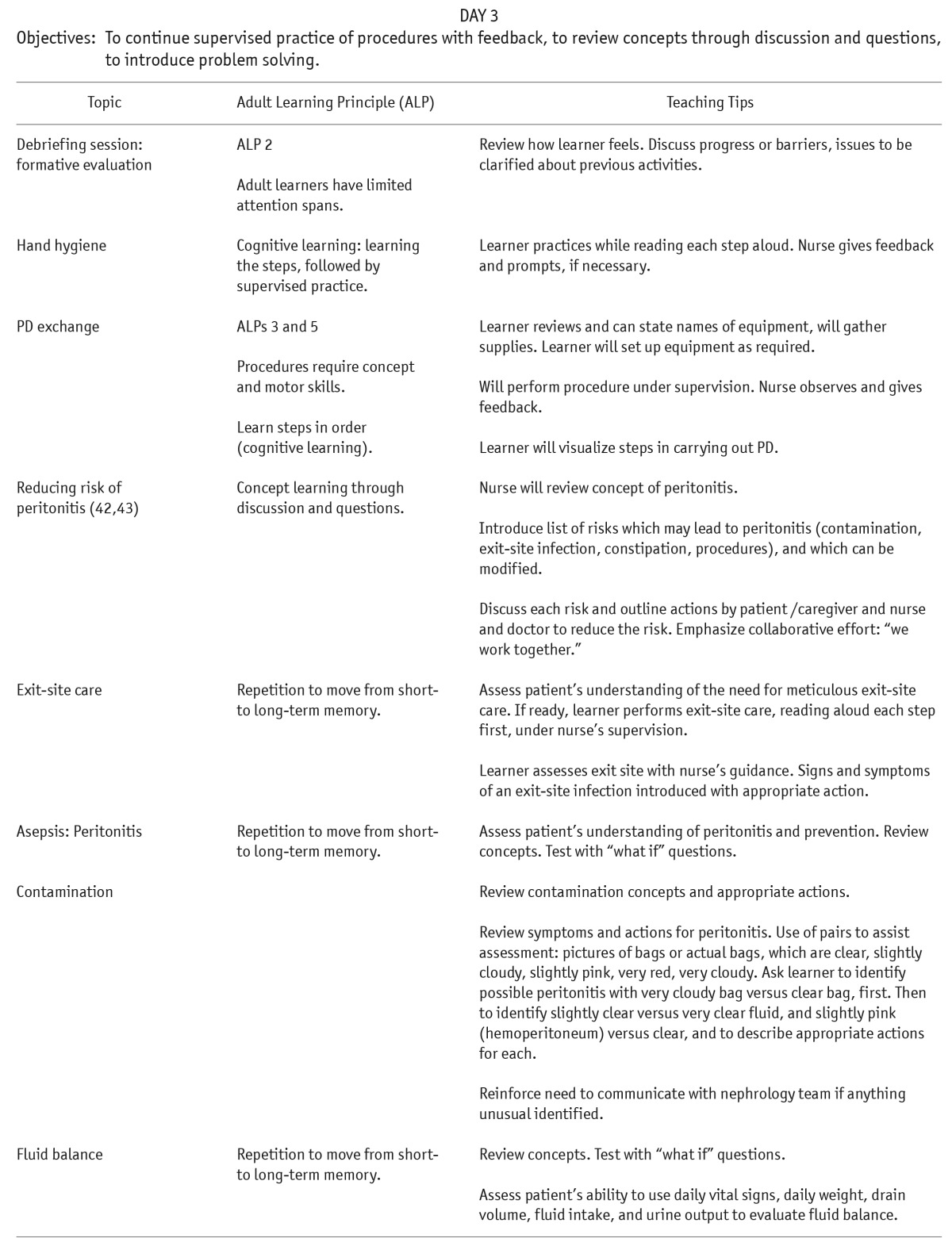

DAY 3

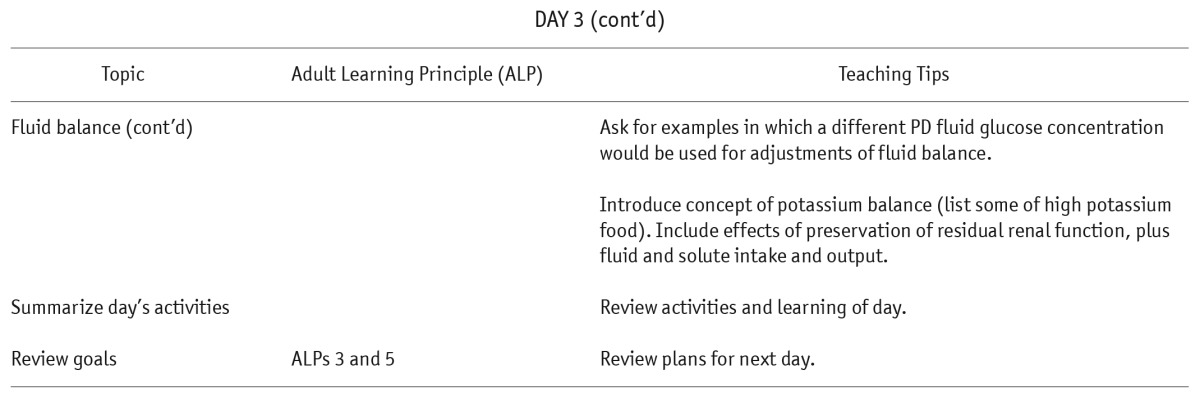

Objectives: To continue supervised practice of procedures with feedback, to review concepts through discussion and questions, to introduce problem solving.

DAY 4

Objectives: To continue supervised procedure practice with feedback, including acknowledgment of skills mastered, review concepts through discussion and questions, continue to problem solve through “what if” scenarios.

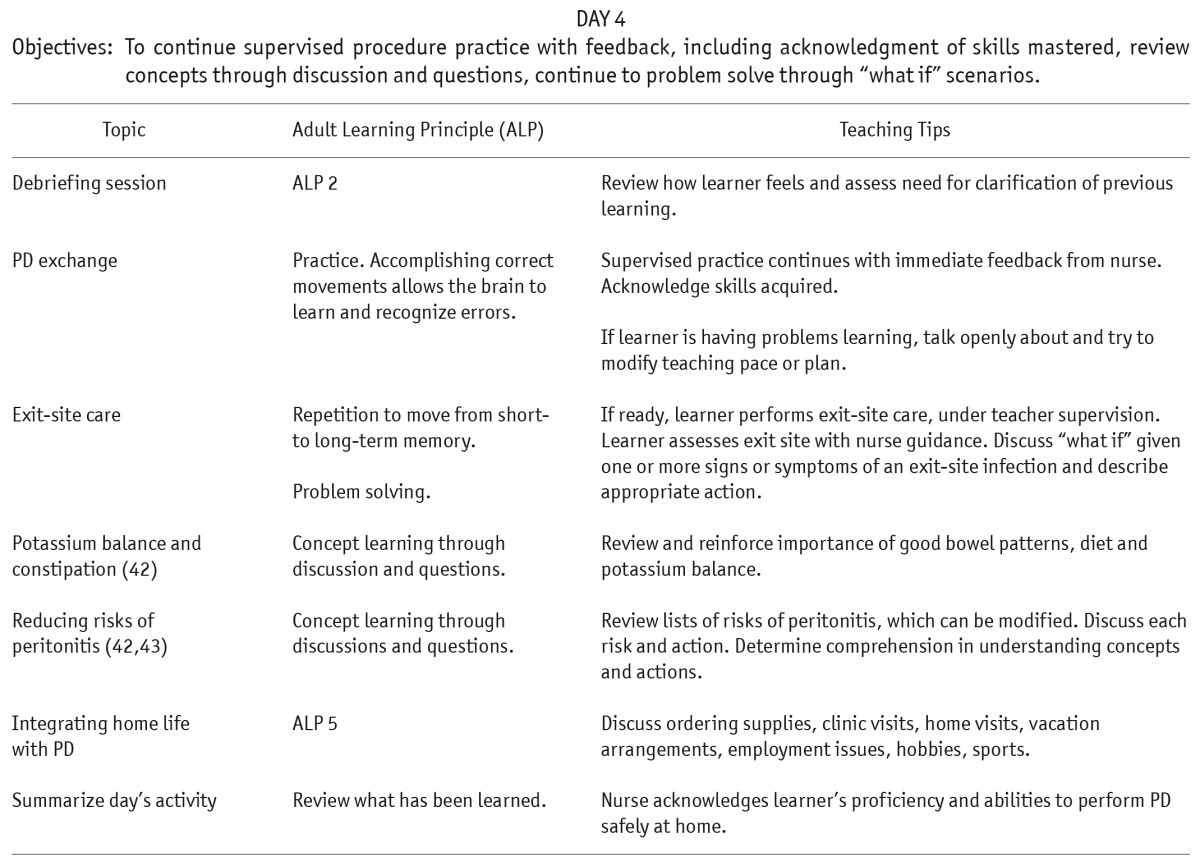

DAY 5

Objectives: To review all previously presented concepts and practice all procedures until proficiency demonstrated.

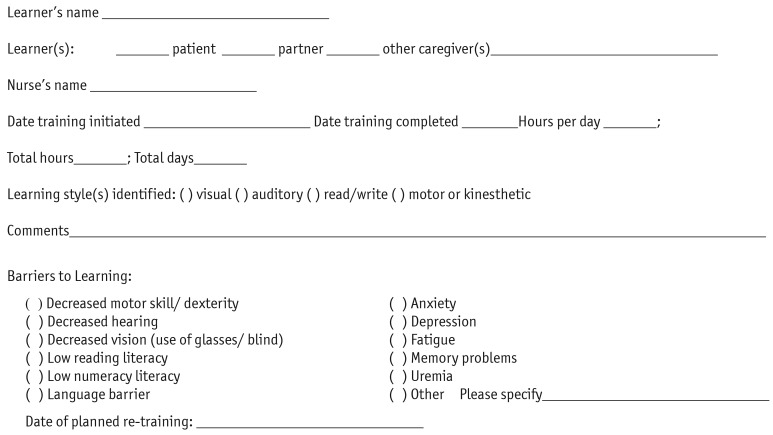

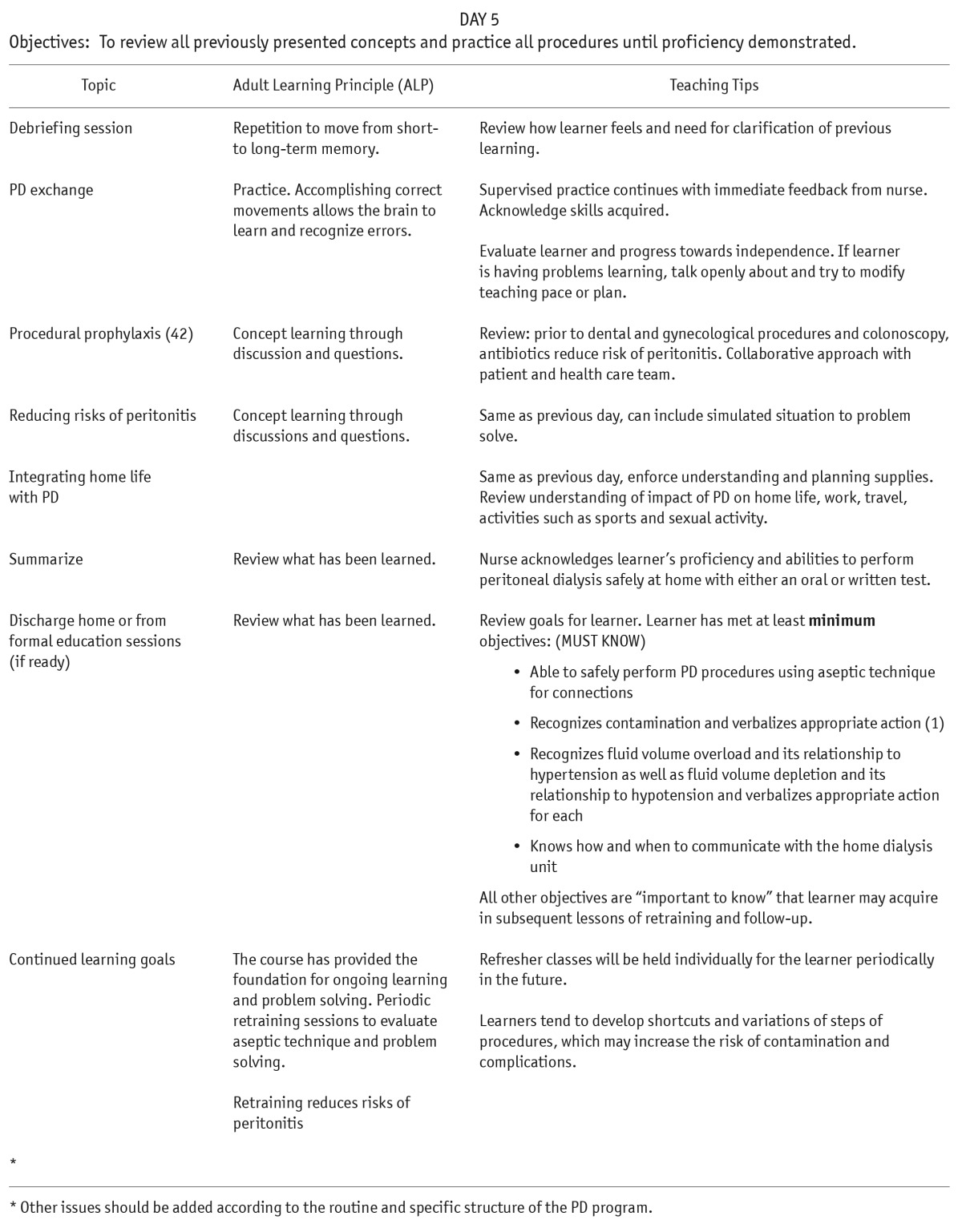

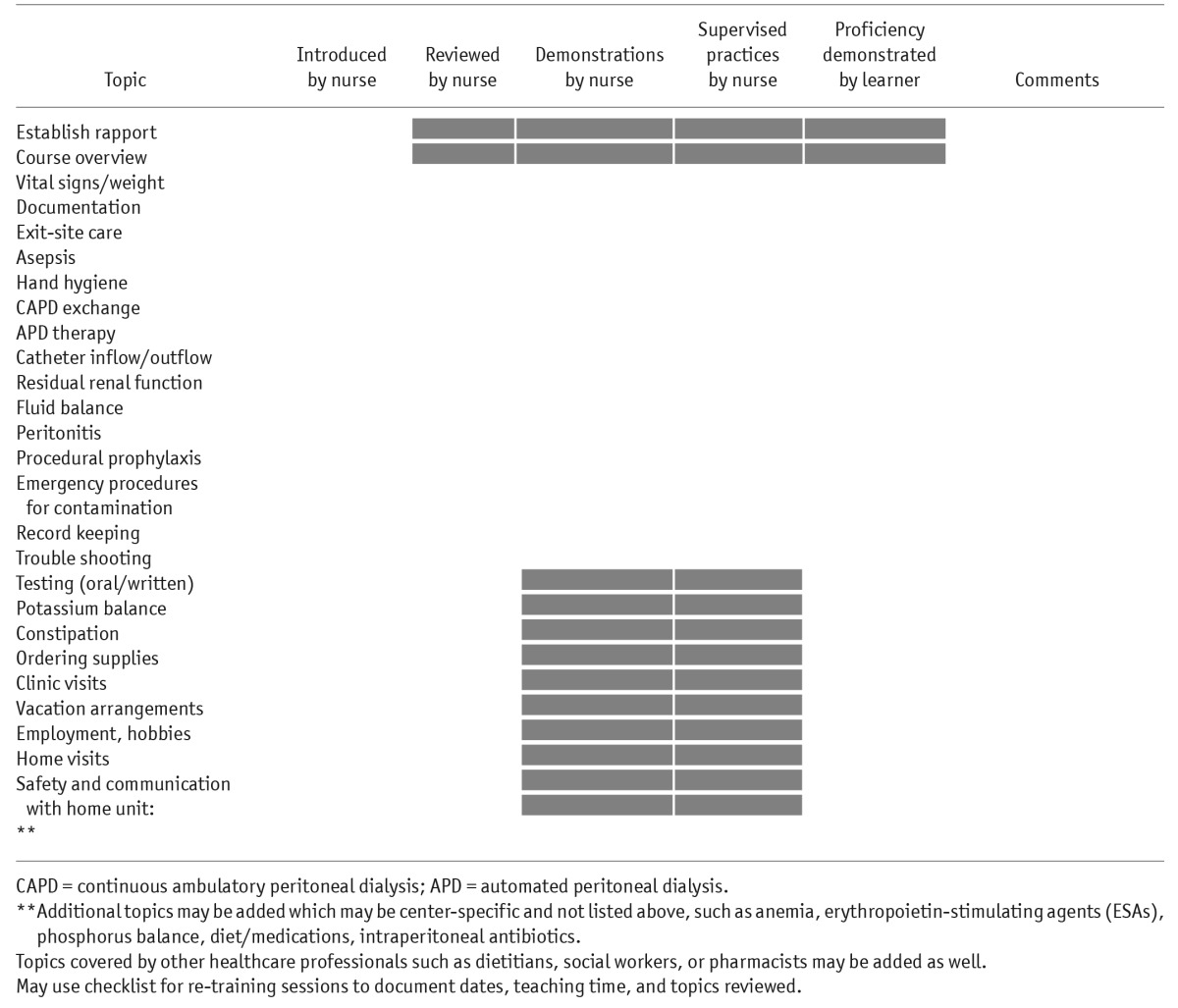

Appendix B

Assessment and Checklist for Peritoneal Dialysis Training

Appendix C

Checklist to be used with the learner to review learning at the end of each day and preview activities planned for the next day. Identify date each time a topic is covered or reviewed. Note: shaded areas to be left empty.

REFERENCES

- 1. Bernardini J, Price V, Figueiredo A. Peritoneal dialysis patient training, 2006. Perit Dial Int 2006; 26(6):625–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Schaepe C, Bergjan M. Educational interventions in peritoneal dialysis: a narrative review of the literature. Int J Nurs Stud 2015; 52(4):882–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Figueiredo AE, de Moraes TP, Bernardini J, Poli-de-Figueiredo CE, Barretti P, Olandoski M, et al. Impact of patient training patterns on peritonitis rates in a large national cohort study. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2015; 30(1):137–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Campbell DJ, Johnson DW, Mudge DW, Gallagher MP, Craig JC. Prevention of peritoneal dialysis-related infections. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2014:gfu313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zhang L, Hawley CM, Johnson DW. Focus on peritoneal dialysis training: working to decrease peritonitis rates. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2015:gfu403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Firanek CA, Sloand JA, Todd LB. Training patients for automated peritoneal dialysis: a survey of practices in six successful centers in the United States. Nephrol Nurs J 2013; 40(6):481–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Russo R, Manili L, Tiraboschi G, Amar K, De Luca M, Alberghini E, et al. Patient re-training in peritoneal dialysis: why and when it is needed. Kidney Int Suppl 2006(103):S127–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bastable SB. Nurse as educator: principles of teaching and learning for nursing practice. Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Figueiredo A, Goh BL, Jenkins S, Johnson DW, Mactier R, Ramalakshmi S, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for peritoneal access. Perit Dial Int 2010; 30(4):424–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Oliver MJ, Garg AX, Blake PG, Johnson JF, Verrelli M, Zacharias JM, et al. Impact of contraindications, barriers to self-care and support on incident peritoneal dialysis utilization. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2010; 25(8):2737–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Knowles MS, Holton EF, III, Swanson RA. The adult learner: the definitive classic in adult education and human resource development. New York, NY: Routledge; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Walker EA. Characteristics of the adult learner. Diabetes Educ 1999; 25(6 Suppl):16–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bruer JT. The mind's journey from novice to expert. Amer Educ 1993; 17(2):6–15. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Beagley L. Educating patients: understanding barriers, learning styles, and teaching techniques. J PeriAnesthesia Nurs 2011; 26(5):331–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fleming N, Baume D. Learning styles again: VARKing up the right tree! Educ Dev 2006; 7(4):4. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cerqueira TCS. Estilos de aprendizagem de Kolb e sua importância na educação. J Learn Styles 2008; 1(1). [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ballerini L, Paris V. Nosogogy: when the learner is a patient with chronic renal failure. Kidney Int Suppl 2006(103):S122–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. George JH, Doto FX. A simple five-step method for teaching clinical skills. Family Med 2001; 33(8):577–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Inott T, Kennedy BB. Assessing learning styles: practical tips for patient education. Nurs Clin N Amer 2011; 46(3):313–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fleming ND, ed. I'm different; not dumb. Modes of presentation (VARK) in the tertiary classroom. Research and Development in Higher Education, Proceedings of the 1995 Annual Conference of the Higher Education and Research Development Society of Australasia (HERDSA), HERDSA 1995; 18:308–13. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Neville A, Jenkins J, Williams JD, Craig KJ. Peritoneal dialysis training: a multisensory approach. Perit Dial Int 2005; 25(Suppl 3):S149–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Shea YF, Lam MF, Lee MS, Mok MY, Lui SL, Yip TP, et al. Prevalence of cognitive impairment among peritoneal dialysis patients, impact on peritonitis and role of assisted dialysis. Perit Dial Int 2016; 36(3):284–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chow KM, Szeto CC, Leung CB, Law MC, Kwan BC, Li PK. Adherence to peritoneal dialysis training schedule. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2007; 22(2):545–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bernardini J, Price V, Figueiredo A, Riemann A, Leung D. International survey of peritoneal dialysis training programs. Perit Dial Int 2006; 26(6):658–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Barone RJ, Campora MI, Gimenez NS, Ramirez L, Santopietro M, Panese SA. The importance of the patient's training in chronic peritoneal dialysis and peritonitis. Adv Perit Dial 2011; 27:97–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. TenBrink T, ed. What learning theory and research can teach us about teaching dialysis patients. In: Workshops I, II, III. 23rd Annual Dialysis Conference; 2003, Seattle, WA. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Coleman EA. Extending simulation learning experiences to patients with chronic health conditions. JAMA 2014; 311(3):243–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. McCormick J. Relating to teaching and learning. In: Molzahn AE, Butera E, ed. Contemporary Nephrology Nursing: Principles and Practice. Pitman, NJ: American Nephrology Nurses' Association; 2006: 885–902. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Nutbeam D. Health literacy as a public health goal: a challenge for contemporary health education and communication strategies into the 21st century. Health Prom Int 2000; 15(3):259–67. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Jain D, Sheth H, Green JA, Bender FH, Weisbord SD. Health literacy in patients on maintenance peritoneal dialysis: prevalence and outcomes. Perit Dial Int 2015; 35(1):96–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. MacKeracher D. Making sense of adult learning. Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ponferrada L, Prowant BF, Schmidt LM, Burrows LM, Satalowich RJ, Bartelt C. Home visit effectiveness for peritoneal dialysis patients. ANNA J / Amer Nephrol Nurs Assoc 1993; 20(3):333–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Farina J. Peritoneal dialysis: a case for home visits. Nephrol Nurs J 2001; 28(4):423–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Peters A. Safety issues in home dialysis. Nephrol Nurs J 2014; 41(1):89–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Blinkhorn TM. Telehealth in nephrology health care: a review. Renal Soc Austral J 2012; 8(3):7. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Diamantidis CJ, Becker S. Health information technology (IT) to improve the care of patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD). BMC Nephrol 2014; 15:7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lew SQ, Sikka N. Are patients prepared to use telemedicine in home peritoneal dialysis programs? Perit Dial Int 2013; 33(6):714–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Rygh E, Arild E, Johnsen E, Rumpsfeld M. Choosing to live with home dialysis-patients' experiences and potential for telemedicine support: a qualitative study. BMC Nephrol 2012; 13(1):13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Harrison TG, Wick J, Ahmed SB, Jun M, Manns BJ, Quinn RR, et al. Patients with chronic kidney disease and their intent to use electronic personal health records. Can J Kidney Health Dis 2015; 2:23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Nayak A, Karopadi A, Antony S, Sreepada S, Nayak KS. Use of a peritoneal dialysis remote monitoring system in India. Perit Dial Int 2012; 32(2):200–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Li PK-T, Szeto CC, Piraino B, Bernardini J, Figueiredo AE, Gupta A, et al. Peritoneal dialysis-related infections recommendations: 2010 update. Perit Dial Int 2010; 30(4):393–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Piraino B, Bernardini J, Brown E, Figueiredo A, Johnson DW, Lye WC, et al. ISPD position statement on reducing the risks of peritoneal dialysis-related infections. Perit Dial Int 2011; 31(6):614–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Bender FH, Bernardini J, Piraino B. Prevention of infectious complications in peritoneal dialysis: best demonstrated practices. Kidney Int Suppl 2006(103):S44–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]