Abstract

Systemic immune-inflammation index (SII), based on peripheral lymphocyte, neutrophil, and platelet counts, was recently investigated as a prognostic marker in several tumors. However, SII has not been reported in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC). We evaluated the prognostic value of the SII in 916 patients with ESCC who underwent radical surgery. Univariate and multivariate analyses were calculated by the Cox proportional hazards regression model. The time-dependent receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curve was used to compare the discrimination ability for OS. PSM (propensity score matching) was carried out to imbalance the baseline characteristics. Our results showed that SII, PLR, NLR and MLR were all associated with OS in ESCC patients in the Kaplan-Meier survival analysis. However, only SII was an independent risk factor for OS (HR = 1.24, 95% CI 1.01–1.53, P = 0.042) among these systemic inflammation scores. The AUC for SII was bigger than PLR, NLR and MLR. In the PSM analysis, SII still remained an independent predictor for OS (HR = 1.30, CI 1.05–1.60, P = 0.018). SII is a novel, simple and inexpensive prognostic predictor for patients with ESCC undergoing radical esophagectomy. The prognostic value of SII is superior to PLR, NLR and MLR.

Esophageal cancer is a common cancer worldwide. In China, it is the 3th leading cancer in incidence and 4th in mortality1. In 2015, there were 477,900 new cases and 375,000 deaths of esophageal cancer in China1. Although the development of its multidisciplinary treatment, five-year overall survival (OS) for esophageal cancer is 15–35% and the prognosis remains poor2. The two main pathological subtypes of esophageal cancer are squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma. In China, esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) accounts for over 90% of cases3. The 7th edition American Joint Committee on Cancer tumor-node-metastasis (AJCC TNM) staging system is used to distinguish the prognosis among different risk groups of ESCC patients. However, ESCC patients at the same TNM stage and received similar therapy usually had variable outcomes. Therefore, it is important to explore dependable prognostic factors.

In recent years, neutrophil, platelet and lymphocyte derived from the peripheral blood were significantly associated with tumor progression in various tumors4,5,6. Some indicators such as neutrophil lymphocyte ratio (NLR) based on neutrophil and lymphocyte, platelet lymphocyte ratio (PLR) based on platelet and lymphocyte, and monocyte lymphocyte ratio (MLR) have emerged as prognostic factors in many cancers, including ESCC7,8,9,10. These indicators only integrate two cells. Systemic immune-inflammation index (SII), based on peripheral lymphocyte, neutrophil, and platelet counts, was recently investigated as a prognostic marker in several tumors including hepatocellular carcinoma11,12, colorectal cancer13 and small cell lung cancer14. However, SII has not been reported in ESCC. In this study, we evaluated the prognostic value of SII in patients with ESCC who underwent radical surgery. We also explore whether SII has more advantages to predict the survival of ESCC population than NLR or PLR. To increase statistical power and to further elaborate on the possible prognostic impact of SII, both Cox’s proportional hazards model analysis as well as propensity score matching (PSM) were applied.

Results

Clinicopathological characteristics of Patient

There were 696 males (76.0%) and 220 females (24.0%) with an age range of 37–84 years (median 60.0 years), of which 46 patients were well differentiated, 450 patients were moderately differentiated, and 420 patients were poorly differentiated. According to the 7th AJCC standard, there were 168 patients at stage 0-I, 395 patients at stage II and 353 patients at stage III. Other clinicopathological features are shown in Table 1. The median OS was 42 months (range, 3 to 146 months) and the rate of 3- and 5-year OS was 52.5% and 44.2%, respectively. Patients with SII > 307 in complete datasets were more likely to be men (P = 0.022), poor differentiation (P = 0.004), advanced T stage (P < 0.001), advanced N stage (P < 0.001) and advanced AJCC TNM stage (P < 0.001) (Table 1). Patients with NLR > 1.7 showed the similar results. PLR > 120 was only associated with advanced AJCC TNM stage (P = 0.015). MLR was associated with sex (P < 0.001), T stage (P = 0.002) and AJCC TNM stage (P < 0.001) in complete datasets (Table 2).

Table 1. Baseline characteristics for patients with SII ≤ 307 versus SII > 307 before and after propensity matching.

| Clinical parameter | Unmatched (complete) dataset | Matched (1:2) dataset | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SII ≤ 307 (253) | SII > 307 (663) | χ2 | P | SII ≤ 307 (253) | SII > 307 (506) | χ2 | P | |

| Sex | 5.24 | 0.022* | 2.33 | 0.127 | ||||

| Male | 179 | 517 | 179 | 384 | ||||

| Female | 74 | 146 | 74 | 122 | ||||

| Age | 0.10 | 0.921 | 0.17 | 0.681 | ||||

| ≤60 | 125 | 330 | 125 | 242 | ||||

| >60 | 128 | 333 | 128 | 264 | ||||

| Histological grade | 12.34 | 0.002* | 1.50 | 0.472 | ||||

| Well differentiated | 23 | 23 | 23 | 39 | ||||

| Moderately differentiated | 116 | 334 | 116 | 255 | ||||

| Poorly or not differentiated | 114 | 306 | 114 | 212 | ||||

| Tumor location | 3.90 | 0.142 | 3.08 | 0.214 | ||||

| Upper | 22 | 35 | 22 | 28 | ||||

| Middle | 164 | 435 | 164 | 329 | ||||

| Lower | 67 | 193 | 67 | 149 | ||||

| T stage | 23.74 | <0.001* | 5.70 | 0.127 | ||||

| 0-T1 | 83 | 125 | 83 | 125 | ||||

| T2 | 64 | 161 | 64 | 149 | ||||

| T3 | 101 | 363 | 101 | 222 | ||||

| T4 | 5 | 14 | 5 | 10 | ||||

| Examined lymph nodes | 2.61 | 0.271 | 2.24 | 0.326 | ||||

| ≤5 | 58 | 141 | 58 | 111 | ||||

| 6–15 | 148 | 366 | 148 | 277 | ||||

| >15 | 47 | 156 | 47 | 118 | ||||

| N stage | 9.96 | 0.019* | 3.65 | 0.302 | ||||

| N0 | 150 | 322 | 150 | 272 | ||||

| N1 | 62 | 208 | 62 | 156 | ||||

| N2 | 28 | 104 | 28 | 57 | ||||

| N3 | 13 | 29 | 13 | 21 | ||||

| 7th AJCC stage | 27.94 | <0.001* | 4.44 | 0.109 | ||||

| 0-I | 74 | 94 | 74 | 114 | ||||

| II | 97 | 298 | 97 | 223 | ||||

| III | 82 | 271 | 82 | 169 | ||||

SII: systemic immune-inflammation index; AJCC: American Joint Committee on Cancer.

Table 2. Relationship between NLR, PLR or MLR and clinicopathological characteristics of patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma.

| Clinical parameter | NLR | PLR | MLR | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤1.7 (290) | >1.7 (626) | χ2 | P | ≤120 (458) | >120 (458) | χ2 | P | ≤0.28 (496) | >0.28 (420) | χ2 | P | |

| Sex | 15.44 | <0.001* | 0.38 | 0.536 | 52.93 | <0.001* | ||||||

| Male | 193 | 503 | 344 | 120 | 330 | 366 | ||||||

| Female | 97 | 123 | 114 | 106 | 166 | 54 | ||||||

| Age | 0.33 | 0.565 | 0.35 | 0.552 | 2.80 | 0.094 | ||||||

| ≤60 | 140 | 315 | 223 | 232 | 259 | 196 | ||||||

| >60 | 150 | 311 | 235 | 226 | 237 | 224 | ||||||

| Histological grade | 8.04 | 0.018* | 3.32 | 0.190 | 5.82 | 0.054 | ||||||

| Well differentiated | 23 | 23 | 29 | 17 | 32 | 14 | ||||||

| Moderately differentiated | 143 | 307 | 223 | 227 | 248 | 202 | ||||||

| Poorly or not differentiated | 124 | 296 | 206 | 214 | 216 | 204 | ||||||

| Tumor location | 8.85 | 0.012* | 0.54 | 0.764 | 5.90 | 0.052 | ||||||

| Upper | 28 | 29 | 28 | 29 | 38 | 19 | ||||||

| Middle | 186 | 413 | 295 | 304 | 329 | 270 | ||||||

| Lower | 76 | 184 | 135 | 125 | 129 | 131 | ||||||

| T stage | 22.21 | <0.001* | 6.67 | 0.083 | 14.56 | 0.002* | ||||||

| 0-T1 | 90 | 118 | 118 | 90 | 133 | 75 | ||||||

| T2 | 77 | 148 | 116 | 109 | 126 | 99 | ||||||

| T3 | 118 | 346 | 216 | 248 | 230 | 234 | ||||||

| T4 | 5 | 14 | 8 | 11 | 7 | 12 | ||||||

| Examined lymph nodes | 0.24 | 0.888 | 0.02 | 0.991 | 1.42 | 0.491 | ||||||

| ≤5 | 63 | 136 | 99 | 100 | 107 | 92 | ||||||

| 6–15 | 160 | 354 | 258 | 256 | 286 | 228 | ||||||

| >15 | 67 | 136 | 101 | 102 | 103 | 100 | ||||||

| N stage | 10.04 | 0.003* | 5.15 | 0.161 | 2.95 | 0.399 | ||||||

| N0 | 171 | 301 | 247 | 225 | 267 | 205 | ||||||

| N1 | 72 | 198 | 131 | 139 | 139 | 131 | ||||||

| N2 | 30 | 102 | 56 | 76 | 66 | 66 | ||||||

| N3 | 17 | 25 | 24 | 18 | 24 | 18 | ||||||

| 7th AJCC TNM stage | 26.39 | <0.001* | 8.43 | 0.015* | 26.39 | <0.001* | ||||||

| 0-I | 81 | 87 | 101 | 67 | 81 | 87 | ||||||

| II | 114 | 281 | 188 | 207 | 114 | 281 | ||||||

| III | 95 | 258 | 169 | 184 | 95 | 258 | ||||||

| SII | 304.85 | <0.001* | 229.49 | <0.001* | 84.56 | <0.001* | ||||||

| ≤307 | 190 | 63 | 229 | 24 | 199 | 54 | ||||||

| >307 | 100 | 563 | 229 | 434 | 297 | 366 | ||||||

| PLR | 107.56 | <0.001* | 81.33 | <0.001* | ||||||||

| ≤120 | 218 | 240 | 316 | 142 | ||||||||

| >120 | 72 | 386 | 180 | 278 | ||||||||

| NLR | — | — | 107.56 | <0.001* | 160.87 | <0.001* | ||||||

| ≤1.7 | — | — | 218 | 72 | 246 | 44 | ||||||

| >1.7 | — | — | 240 | 386 | 250 | 376 | ||||||

| MLR | 160.87 | <0.001* | 81.33 | <0.001* | — | — | ||||||

| ≤0.28 | 246 | 250 | 316 | 180 | — | — | ||||||

| >0.28 | 44 | 376 | 142 | 278 | — | — | ||||||

SII: systemic immune-inflammation index; PLR: platelet lymphocyte ratio; NLR: neutrophil lymphocyte ratio; MLR: monocyte lymphocyte ratio; AJCC: American Joint Committee on Cancer.

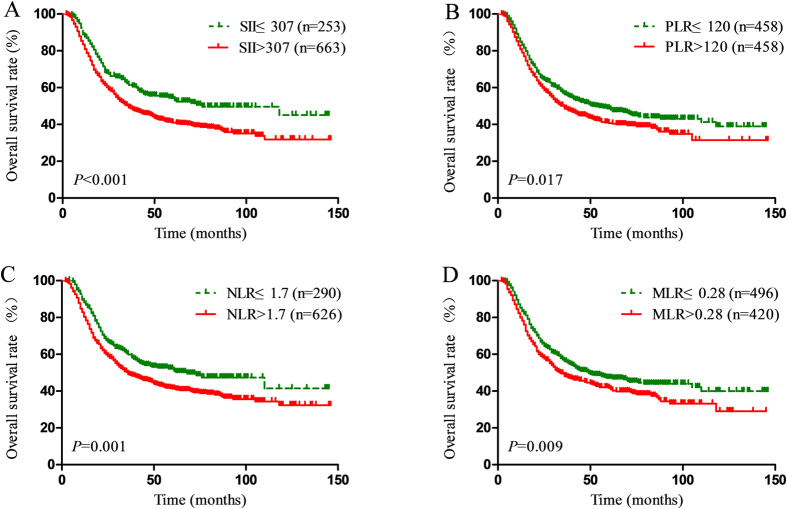

The prognostic significance of SII, NLR, PLR and MLR

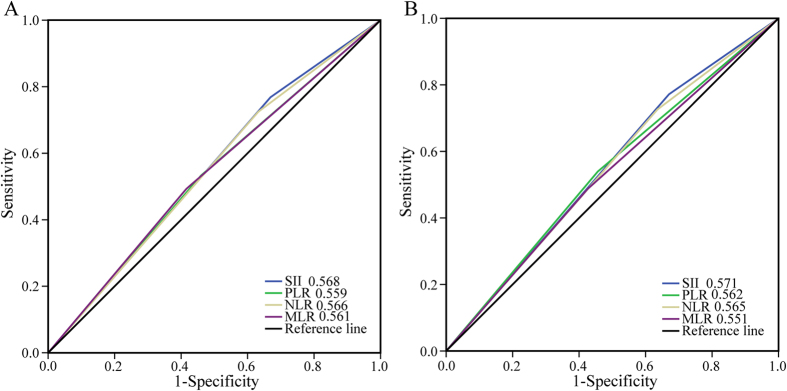

The Kaplan-Meier survival analysis showed that high SII, PLR, NLR and MLR scores were all associated with poor OS in ESCC patients (P < 0.001, P = 0.017, P = 0.001, P = 0.009, respectively) (Fig. 1). The median OS was 76 months for patients with SII ≤ 307 and 36 months for patients with SII > 307. In addition, patients with PLR ≤ 120 had a median OS of 53 months, whereas patients with PLR > 120 had a median OS of 36 months. Patients with NLR ≤ 1.7 had a median OS with 68 months, compared with 36 months for the patients with NLR > 1.7. Patients with MLR ≤ 0.28 had a median OS with 49 months, compared with 34 months for patients with MLR > 0.28. Based on the univariate analysis, sex, histological grade, T stage, N stage, SII, PLR, NLR and MLR were identified as the significant prognostic factors (Table 3). It was found that SII, PLR, NLR and MLR were highly correlated and had the same factors. There four separate multivariate models (SII, PLR, NLR and MLR) were run to avoid problems with the presence of multicollinearity. Multivariate analyses demonstrated that histological grade, T stage, N stage, and SII were independent risk factors for OS (Table 3). Among SII, NLR, PLR and MLR, only SII was an independent risk factor for OS (HR = 1.24, 95% CI 1.01–1.53, P = 0.042). In addition, the discrimination ability of SII, PLR, NLR and MLR was compared by the AUC for OS. The AUC for SII was bigger than SII, NLR, PLR and MLR for predicting survival in patients with ESCC in 3-years and 5-years (Fig. 2). It means SII is superior to NLR, PLR or MLR as a predictive factor in ESCC patients.

Figure 1.

Kaplan–Meier survival curves for patients stratified based on (A) SII, (B) PLR, (C) NLR and (D) MLR in unmatched complete datasets.

Table 3. Univariate and multivariate cox regression analyses for overall survival in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (unmatched complete datasets).

| Variables | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95%CI) | P value | HR (95%CI) | P value | |

| Sex | ||||

| Male vs. Female | 1.39 (1.12–1.73) | 0.003* | 1.15 (0.93–1.44) | 0.206a |

| Age | ||||

| ≤60 years vs. >60 years | 1.12 (0.94–1.33) | 0.207 | ||

| Histological grade | <0.001* | <0.001*,a | ||

| Well differentiated | Ref. | — | Ref. | |

| Moderately differentiated | 3.96 (1.87–8.40) | <0.001 | 2.29 (1.06–1.49) | 0.034 |

| Poorly or not differentiated | 6.23 (2.94–13.20) | <0.001 | 3.20 (1.49–6.86) | 0.003 |

| Tumor location | 0.708 | |||

| Upper | Ref. | |||

| Middle | 1.04 (0.72–1.50) | 0.855 | ||

| Lower | 0.95 (0.64–1.41) | 0.802 | ||

| T stage | <0.001* | <0.001*,a | ||

| 0-T1 | Ref. | — | Ref. | |

| T2 | 1.74 (1.28–2.38) | <0.001 | 1.38 (1.01–1.90) | 0.045 |

| T3 | 3.30 (2.52–4.31) | <0.001 | 2.08 (1.48–2.94) | <0.001 |

| T4 | 4.75 (2.71–8.35) | <0.001 | 3.38 (1.79–6.40) | <0.001 |

| Examined lymph nodes | 0.158 | |||

| ≤5 | Ref. | — | ||

| 6–15 | 0.96 (0.77–1.19) | 0.679 | ||

| >15 | 1.18 (0.91–1.52) | 0.208 | ||

| N stage | <0.001* | <0.001*,a | ||

| N0 | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| N1 | 2.13 (1.73–2.62) | <0.001 | 1.66 (1.34–2.06) | <0.001 |

| N2 | 3.82 (2.99–4.87) | <0.001 | 2.68 (2.08–3.46) | <0.001 |

| N3 | 5.45 (3.83–7.77) | <0.001 | 4.23 (2.95–6.05) | <0.001 |

| SII | ||||

| >307 vs. ≤307 | 1.44 (1.17–1.77) | 0.001* | 1.24 (1.01–1.53) | 0.042*,a |

| PLR | ||||

| >120 vs. ≤120 | 1.23 (1.03–1.47) | 0.020* | 1.18 (0.99–1.40) | 0.070b |

| NLR | ||||

| >1.7 vs. ≤1.7 | 1.35 (1.11–1.65) | 0.002* | 1.18 (0.97–1.44) | 0.107c |

| MLR | ||||

| >0.28 vs. ≤0.28 | 1.26 (1.06–1.50) | 0.010* | 1.12 (0.94–1.34) | 0.220d |

SII: systemic immune-inflammation index; PLR: platelet lymphocyte ratio; NLR: neutrophil lymphocyte ratio; MLR: monocyte lymphocyte ratio; HR: hazard ratio; CI: confidence interval; Ref: reference. aThe variables (sex, histological grade, T stage, N stage and SII) were tested in a multivariate analysis. bThe variables (sex, histological grade, T stage, N stage and PLR) were tested in a multivariate analysis. cThe variables (sex, histological grade, T stage, N stage and NLR) were tested in a multivariate analysis. dThe variables (sex, histological grade, T stage, N stage and MLR) were tested in a multivariate analysis.

Figure 2.

Predictive ability of the SII was compared with PLR, NLR and MLR by ROC curves in 3-years (A) and 5-years (B).

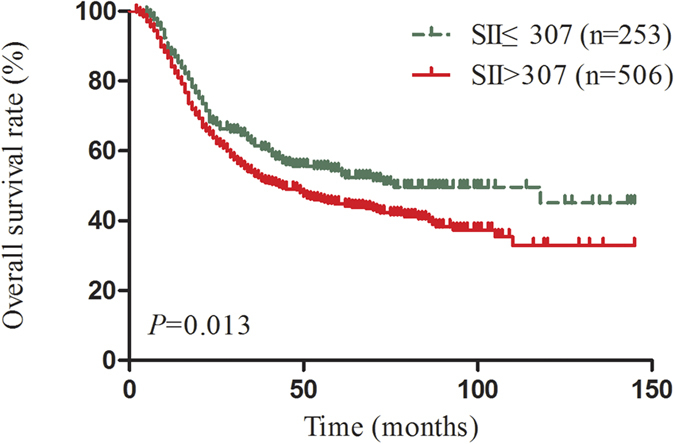

Propensity score matching analysis

Considered the sex, histological grade, T stage, N stage and AJCC TNM stage were imbalance between SII ≤ 307 and SII > 307 ESCC patients (Table 1), we applied a 1:2 PSM ratio to minimize these differences. In the PSM analysis, we selected 253 patients from SII ≤ 307 group with matched pairings of the 506 SII > 307 patients using a nearest-neighbour algorithm. These clinicopathological characteristics were balanced and evenly distributed between these groups (all P > 0.1) (Table 1). The Kaplan-Meier survival curves for the matched groups are shown in Fig. 3. In the matched 759 patients’ survival analysis, median OS was 76 months for SII ≤ 307 ESCC patients and 43 months for SII > 307 ESCC patients. The 5-year survival was 55.4% in SII ≤ 307 ESCC patients versus 44.9% in SII > 307 ESCC patients. In addition, the multivariate analyses showed SII still remained an independent predictor for OS (HR = 1.30, CI 1.05-1.60, P = 0.018) (Table 4).

Figure 3. Kaplan-Meier-estimated overall survival distributions from matched datasets for SII ≤ 307 versus SII > 307.

Table 4. Univariate and multivariate cox regression analyses for overall survival in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (matched datasets, 1:2).

| Variables | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95%CI) | P value | HR (95%CI) | P value | |

| Sex | ||||

| Male vs. Female | 1.29 (1.02–1.63) | 0.036* | 1.12 (0.88–1.43) | 0.344 |

| Age | ||||

| ≤60 years vs. >60 years | 1.14 (0.93–1.38) | 0.207 | ||

| Histological grade | <0.001* | <0.001* | ||

| Well differentiated | Ref. | — | Ref. | |

| Moderately differentiated | 3.81 (1.79–8.10) | 0.001 | 2.10 (0.98–4.53) | 0.058 |

| Poorly or not differentiated | 5.90 (2.77–12.53) | <0.001 | 3.00 (1.39–6.45) | 0.005 |

| Tumor location | 0.540 | |||

| Upper | Ref. | |||

| Middle | 0.89 (0.60–1.32) | 0.560 | ||

| Lower | 0.81 (0.53–1.23) | 0.319 | ||

| T stage | <0.001* | <0.001* | ||

| 0-T1 | Ref. | — | Ref. | |

| T2 | 1.69 (1.22–2.29) | 0.001 | 1.33 (0.97–1.84) | 0.079 |

| T3 | 3.33 (2.52–4.38) | <0.001 | 2.11 (1.58–2.83) | <0.001 |

| T4 | 4.08 (2.15–7.75) | <0.001 | 2.44 (1.27–4.69) | 0.007 |

| Examined lymph nodes | 0.074 | |||

| ≤5 | Ref. | — | ||

| 6–15 | 0.93 (0.73–1.18) | 0.549 | ||

| >15 | 1.28 (0.96–1.70) | 0.087 | ||

| N stage | <0.001* | <0.001* | ||

| N0 | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| N1 | 2.43 (1.93–3.06) | <0.001 | 1.78 (1.40–2.28) | <0.001 |

| N2 | 4.39 (3.28–5.87) | <0.001 | 3.12 (2.30–4.23) | <0.001 |

| N3 | 6.89 (4.66–10.21) | <0.001 | 5.63 (3.77–8.40) | <0.001 |

| SII | ||||

| >307 vs. ≤307 | 1.31 (1.06–1.63) | 0.014* | 1.30 (1.05–1.62) | 0.018* a |

| PLR | ||||

| >120 vs. ≤120 | 1.17 (0.96–1.43) | 0.112 | ||

| NLR | ||||

| >1.7 vs. ≤1.7 | 1.30 (1.05–1.61) | 0.016* | 1.20 (0.97–1.49) | 0.093b |

| MLR | ||||

| >0.28 vs. ≤0.28 | 1.19 (0.98–1.45) | 0.080 | ||

SII: systemic immune-inflammation index; HR: hazard ratio; CI: confidence interval; Ref: reference. aThe variables (sex, histological grade, T stage, N stage and SII) were tested in a multivariate analysis. bThe variables (sex, histological grade, T stage, N stage and NLR) were tested in a multivariate analysis.

Discussion

Inflammation has been known as a hallmark feature of tumor15. The correlation between inflammation and tumor was first reported by Rudolf Virchow in 186316. Recently, accumulating evidence has indicated that inflammation contributes to tumor development, progression and metastasis. Systemic inflammatory scores such as NLR, PLR and MLR have been found to be independent markers of prognosis in a variety of cancers, including ESCC7,8,9,10. A novel systemic inflammation score-SII, based on neutrophil, platelet, and lymphocyte counts, was shown to be an independent risk of recurrence and survival for hepatocellular carcinoma, small cell lung cancer, colorectal cancer and gastric cancer patients11,12,13,14,17. It was considered to be better than PLR and NLR, and was associated with higher circulating tumor cells (CTCs) levels. In the present study, SII was confirmed to be a novel independent predictor of survival for patients with resectable ESCC by a multivariable Cox regression analysis and PSM analysis. It was shown to be superior to NLR, PLR and MLR as a predictive factor in ESCC patients. Compared with other prognostic factors, the inflammation-based prognostic scores are simple, inexpensive and routinely performed in clinical practice. Meanwhile, SII based on standard laboratory measurements of total platelet, neutrophil, and lymphocyte counts is simple, inexpensive and routinely performed in clinical practice. Thus, there is a potential for SII to be used as a marker for prognosis and treatment response surveillance.

Several potential mechanisms may be used to explain the prognostic values of SII in tumor. Cancer-mediated myelopoiesis has been recognised in the promotion of tumor angiogenesis, cell invasion, and metastasis in recent years. In contrast with myelopoiesis during acute infection, stress, or trauma in which circulating immune cells are transient increase, cancer myelopoiesis is associated with persistence of immature myeloid cells18. Firstly, neutrophils are not released from the bone marrow until mature ordinarily, however, in the context of inflammation, they were triggered by secretion of cytokines and chemokines, such as interleukin-6 (IL-6), tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and myeloid growth factors19. These inflammatory mediators enhance the invasion, proliferation, and metastasis of cancer cell, aid cancer cells to evade immune surveillance, and induce the resistance to cytotoxic drugs6,20. The elevated neutrophils can also release plenty of nitric oxide, arginase, and reactive oxygen species (ROS), leading to T cell activation disorders21. Secondly, platelets can protect CTCs from shear stresses during circulation, induce epithelial-mesenchymal transition, and promote tumor cell extravasation to metastatic sites4,22. Meanwhile, platelets and neutrophils have been reported to promote adhesion and seeding of distant organ sites through secreting vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)5,11,23. Thirdly, lymphocytes can also secrete several cytokines, such as IFN-γ and TNF-α, to control tumor growth and improve prognosis of cancer patients24, and the decreased lymphocyte count and function will impair cancer immune surveillance and defense6,24.

Based on the above theory, SII should be a more objective marker that reflects the balance between host inflammatory and immune response status than all the other systemic inflammation index such as the PLR and NLR. In fact, our results confirmed that SII is indeed superior to PLR, NLR and MLR. In addition, many studies have confirmed that non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are associated with improved survival outcomes in patients with cancer, including esophageal cancer25,26. The patients with ESCC who have a high SII maybe especially benefit from targeted anti-inflammatory with aspirin and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).

Although our results demonstrated the prognostic value of SII in ESCC, there are still several limitations in this study. First, it should be noted that most patients with esophageal cancer in China are squamous cell carcinoma, while the most esophageal cancer is adenocarcinoma in western. Therefore, the prognostic significance of SII needs to be validated in patients with esophageal adenocarcinoma. Second, our study was a retrospective study, and there may be selection bias during retrospective data collection. However, we used PSM analysis which can minimize group differences in the baseline characteristics. Third, the majority (77.8%) of patients enrolled in this study had dissected lymph nodes with <15, so further studies for patients with adequate lymphadenectomy are needed to confirm our results. Fourth, our study is a single retrospective center research study. Thus, a multicenter collaborative prospective study is required to be further verified in a prospective, large-scale collaborative study.

In conclusion, SII is a novel independent prognostic predictor for patients with ESCC undergoing radical esophagectomy. The prognostic value of SII is superior to PLR, NLR and MLR. Based on simple and inexpensive standard laboratory measurements, SII will be a potential marker for ESCC prognosis and treatment response surveillance.

Materials and Methods

Patients

A retrospective analysis was conducted in patients who underwent radical esophagectomy at the Third Affiliated Hospital of Soochow University (Changzhou, China) from January 2002 to December 2012. The dissection area for lymphadenectomy was described as our previous article27. All patients received transthoracic radical esophagectomy with mediastinal and abdominal two-field lymphadenectomies. The scope of mediastinal lymphadenectomies included subcarinal, left and right bronchial, lower posterior mediastinum, pulmonary ligament, and paraesophageal and thoracic duct nodes. The scope of abdominal lymphadenectomies included the paracardial, lesser curvature, left gastric, common hepatic, celiac, and splenic nodes. The paratracheal and recurrent laryngeal nerve LNs were also dissected. Cervical lymphadenectomy was not conventionally performed, except for cases of suspicious cervical lymphadenopathy. The inclusion criteria were as follows: ESCC was confirmed by histopathology, R0 resection, no preoperative or postoperative radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy. At last, 916 patients were enrolled in the current study. The patient follow-up started from the date of surgery and continued up until December 2014 or patients’ death. All the patients received postoperative follow-up every 3 months within two years after the operation, and the median follow-up time was 39 months (3–146 months). This study was undertaken according to the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Third Affiliated Hospital of Soochow University. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Data on preoperative peripheral neutrophil, lymphocyte, and platelet counts were extracted from the medical records. The definitions of SII, NLR and PLR are described as follows: SII = platelet*neutrophil/lymphocyte; NLR = neutrophil/lymphocyte; PLR = platelet/lymphocyte. The optimal cutoff values including SII (SII ≤ 307, SII > 307), NLR (NLR ≤ 1.7, NLR > 1.7), PLR (PLR ≤ 120, PLR > 120) and MLR (MLR ≤ 0.28, NLR > 0.28) were determined by using X-tile software (http://www.tissuearray.org/rimmlab)28.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted with SPSS 22.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL), Graphpad Prism 6.01 (La Jolla, CA, USA) and R software 3.2.5 (http://www.r-project.org/) with MatchIt packages. The correlations between the inflammation-based prognostic scores and clinicopathological characteristics were analyzed by the χ2 test. Correlation analysis is using Person’s correlation test. Survival curves were plotted using the Kaplan-Meier method and compared using the log-rank test. Univariate and multivariate analyses were calculated by the Cox proportional hazards regression model. The time-dependent receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curve was used to compare the discrimination ability for OS. PSM was carried out because of imbalance in the baseline characteristics. PSM was done with a nearest-neighbour matching algorithm, allowing a maximum tolerated difference between propensity scores less than 30% of the propensity score SD. A P value less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant unless otherwise specified.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Geng, Y. et al. Systemic Immune-Inflammation Index Predicts Prognosis of Patients with Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma: A Propensity Score-matched Analysis. Sci. Rep. 6, 39482; doi: 10.1038/srep39482 (2016).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31570877 and 81301960).

Footnotes

Author Contributions Y.T.G., C.P.W. and J.T.J. conceived and designed the study and helped to draft the manuscript. Y.J.S. performed the statistical analysis. D.X.Z., X.Z., Q.Z., W.J.Z. and X.F.N. performed the data collection. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

References

- Chen W. et al. Cancer statistics in China, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin 66, 115–132 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennathur A., Gibson M. K., Jobe B. A. & Luketich J. D. Oesophageal carcinoma. Lancet 381, 400–412 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamangar F., Dores G. M. & Anderson W. F. Patterns of cancer incidence, mortality, and prevalence across five continents: defining priorities to reduce cancer disparities in different geographic regions of the world. J Clin Oncol 24, 2137–2150 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labelle M., Begum S. & Hynes R. O. Direct signaling between platelets and cancer cells induces an epithelial-mesenchymal-like transition and promotes metastasis. Cancer Cell 20, 576–590 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cools-Lartigue J. et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps sequester circulating tumor cells and promote metastasis. J Clin Invest (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantovani A., Allavena P., Sica A. & Balkwill F. Cancer-related inflammation. Nature 454, 436–444 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J. S., Huang Y., Yang X. & Feng J. F. A nomogram to predict prognostic values of various inflammatory biomarkers in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Am J Cancer Res 5, 2180–2189 (2015). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao Y. et al. Prognostic nomogram integrated systemic inflammation score for patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma undergoing radical esophagectomy. Sci Rep 5, 18811 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yutong H. et al. Increased Neutrophil-Lymphocyte Ratio Is a Poor Prognostic Factor in Patients with Esophageal Cancer in a High Incidence Area in China. Arch Med Res 46, 557–563 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yodying H. et al. Prognostic Significance of Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio and Platelet-to-Lymphocyte Ratio in Oncologic Outcomes of Esophageal Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Ann Surg Oncol 23, 646–654 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu B. et al. Systemic immune-inflammation index predicts prognosis of patients after curative resection for hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 20, 6212–6222 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z. et al. Aspartate aminotransferase-lymphocyte ratio index and systemic immune-inflammation index predict overall survival in HBV-related hepatocellular carcinoma patients after transcatheter arterial chemoembolization. Oncotarget 6, 43090–43098 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passardi A. et al. Inflammatory indexes as predictors of prognosis and bevacizumab efficacy in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Oncotarget (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong X. et al. Systemic Immune-inflammation Index, Based on Platelet Counts and Neutrophil-Lymphocyte Ratio, Is Useful for Predicting Prognosis in Small Cell Lung Cancer. Tohoku J Exp Med 236, 297–304 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanahan D. & Weinberg R. A. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell 144, 646–674 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balkwill F. & Mantovani A. Inflammation and cancer: back to Virchow? Lancet 357, 539–545 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang L. et al. Systemic immune-inflammation index, thymidine phosphorylase and survival of localized gastric cancer patients after curative resection. Oncotarget (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabrilovich D. I., Ostrand-Rosenberg S. & Bronte V. Coordinated regulation of myeloid cells by tumours. Nat Rev Immunol 12, 253–268 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuper H., Adami H. O. & Trichopoulos D. Infections as a major preventable cause of human cancer. J Intern Med 248, 171–183 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diakos C. I., Charles K. A., McMillan D. C. & Clarke S. J. Cancer-related inflammation and treatment effectiveness. Lancet Oncol 15, e493–503 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller I., Munder M., Kropf P. & Hansch G. M. Polymorphonuclear neutrophils and T lymphocytes: strange bedfellows or brothers in arms? Trends Immunol 30, 522–530 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher D., Strilic B., Sivaraj K. K., Wettschureck N. & Offermanns S. Platelet-derived nucleotides promote tumor-cell transendothelial migration and metastasis via P2Y2 receptor. Cancer Cell 24, 130–137 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusumanto Y. H., Dam W. A., Hospers G. A., Meijer C. & Mulder N. H. Platelets and granulocytes, in particular the neutrophils, form important compartments for circulating vascular endothelial growth factor. Angiogenesis 6, 283–287 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrone C. & Dranoff G. Dual roles for immunity in gastrointestinal cancers. J Clin Oncol 28, 4045–4051 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bains S. J. et al. Aspirin As Secondary Prevention in Patients With Colorectal Cancer: An Unselected Population-Based Study. J Clin Oncol (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Staalduinen J. et al. The effect of aspirin and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use after diagnosis on survival of oesophageal cancer patients. Br J Cancer 114, 1053–1059 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ning Z. H. et al. Proposed Modification of Nodal Staging as an Alternative to the Seventh Edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer Tumor-Node-Metastasis Staging System Improves the Prognostic Prediction in the Resected Esophageal Squamous-Cell Carcinoma. J Thorac Oncol 10, 1091–1098 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camp R. L., Dolled-Filhart M. & Rimm D. L. X-tile: a new bio-informatics tool for biomarker assessment and outcome-based cut-point optimization. Clin Cancer Res 10, 7252–7259 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]