Abstract

Adjudicated youth in residential treatment facilities (RTFs) have high rates of trauma exposure and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). This study evaluated strategies for implementing trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy (TF-CBT) in RTF. Therapists (N = 129) treating adjudicated youth were randomized by RTF program (N = 18) to receive one of the two TF-CBT implementation strategies: (1) web-based TF-CBT training + consultation (W) or (2) W + 2 day live TF-CBT workshop + twice monthly phone consultation (W + L). Youth trauma screening and PTSD symptoms were assessed via online dashboard data entry using the University of California at Los Angeles PTSD Reaction Index. Youth depressive symptoms were assessed with the Mood and Feelings Questionnaire–Short Version. Outcomes were therapist screening; TF-CBT engagement, completion, and fidelity; and youth improvement in PTSD and depressive symptoms. The W + L condition resulted in significantly more therapists conducting trauma screening (p = .0005), completing treatment (p = .03), and completing TF-CBT with fidelity (p = .001) than the W condition. Therapist licensure significantly impacted several outcomes. Adjudicated RTF youth receiving TF-CBT across conditions experienced statistically and clinically significant improvement in PTSD (p = .001) and depressive (p = .018) symptoms. W + L is generally superior to W for implementing TF-CBT in RTF. TF-CBT is effective for improving trauma-related symptoms in adjudicated RTF youth. Implementation barriers are discussed.

Keywords: trauma-focused CBT, implementation, dissemination, adjudicated youth, juvenile justice, PTSD, trauma, evidence-based treatment

Introduction

More than 90,000 juvenile offenders are housed in over 2,000 U.S. residential juvenile justice facilities annually, the most common (35%) being residential treatment facilities (RTFs). Youth are adjudicated to RTF in order to be in a contained setting where mental health therapy can be provided. The focus of RTF treatment is most typically to decrease serious externalizing behavior problems and to prevent recidivism, per the juvenile justice system mandate; other reasons may be to address serious suicidal risk and other serious mental health problems. For a variety of reasons, trauma exposure and symptoms are rarely systematically assessed, and evidence-based trauma treatment is seldom provided in juvenile justice RTF settings. The feasibility of implementing evidence-based trauma-focused treatment in these settings, using more or less intensive training and consultation strategies, has not been established. To address this gap, the current study compared two strategies for therapist implementation of trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy (TF-CBT) for adjudicated youth in RTF settings.

This issue is important for a number of reasons. Child trauma is a significant risk factor for subsequent violent offending in adolescence and adulthood. Maltreatment doubles the risk of engaging in crime, and risk increases further if youth experience multiple traumas (Currie & Tekin, 2006). Rates of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) among adjudicated youth are 5–8 times higher than those found in community samples of similar aged peers (Ford, Chapman, Hawke, & Albert, 2007). A recent study of 350 juvenile justice–involved youth in two states showed PTSD rates of almost 50% (Rosenberg et al., 2014).

Providing effective trauma treatment to trauma-affected adjudicated youth in RTF settings can mitigate trauma-related behaviors before these escalate further. RTF offers some advantages to outpatient settings for this challenging population. In RTF, youth are more available to participate in treatment in an ongoing manner, and not subject to as many factors that interfere with therapy in outpatient settings. The RTF setting may feel (and actually be) safer for these youth than their home or community, thus providing an environment more conducive to successful trauma processing. Developing cost-effective strategies for disseminating and implementing evidence-based trauma treatment in juvenile justice RTF settings is thus potentially beneficial for adjudicated youth as well as for their families and society.

Trauma-Focused Treatment for Adjudicated Youth in RTF

TF-CBT (Cohen, Mannarino, & Deblinger, 2006) is an evidence-based trauma treatment with substantial evidence of improving PTSD symptoms as well as affective, cognitive, and behavioral problems in youth populations (Cohen, Deblinger, Mannarino, & Steer, 2004; Cohen, Mannarino, & Iyengar, 2011). TF-CBT requires the appropriate identification and engagement of traumatized youth and caregivers and the delivery of nine treatment components: psychoeducation, relaxation skills, affective modulation skills, cognitive coping skills, trauma narration and processing, in vivo mastery of trauma reminders, conjoint youth–parent sessions, and enhancing safety and future development. These components are summarized by the acronym “PRACTICE” (Cohen et al., 2006). All of these components except in vivo mastery are completed in RTF settings (Cohen, Mannarino, & Navarro, 2012). The components are generally provided in the order described above. Some specified variation in the order of components is acceptable for youth with complex trauma responses, who are often seen in RTF settings (Cohen, Mannarino, Kliethermes, & Murray, 2012). Weekly sessions are provided to youth and also to caregivers when they are available. Caregivers may participate via phone or secure Skype when in-person attendance is not feasible (e.g., the RTF is far from the home). If no caregiver is available to participate in treatment, the youth can invite a direct care RTF staff member to participate instead of the caregiver (Cohen, Mannarino & Navarro, 2012).

TF-CBT has been evaluated in 16 randomized trials for youth ages 3–18 years who have experienced diverse types of trauma including the multiple and interpersonal traumas that typically affect adjudicated youth (Mannarino & Cohen, 2014). TF-CBT applications are available for youth who have experienced early chronic trauma and have complex trauma responses (Cohen, Mannarino, Kliethermes et al., 2012), and specifically for youth in RTF settings (Cohen, Mannarino, & Navarro, 2012). Recent studies of adolescents with chronic early trauma histories and comorbid conduct symptoms support the effectiveness of TF-CBT for improving multiple outcomes including PTSD symptoms, behavior problems, depressive and anxiety symptoms, and prosocial behaviors (McMullen, O’Callaghan, Shannon, Black, & Eakin, 2013; O’Callaghan, McMullen, Shannon, Rafferty, & Black, 2013).

Implementation and Dissemination of TF-CBT in RTFs

Requirements for successfully implementing and disseminating evidence-based treatments have been well characterized (Fixsen, Naoom, Blasé, Friedman, & Wallace, 2005). These include identifying a well-established model, provided by expert trainers who champion the model’s use, and therapists who want to use it. Also needed is ongoing feedback to address implementation challenges, occurring within a setting that supports the model’s ongoing use (Fixsen et al., 2005). Problems at the therapist, client, and/or organizational levels can influence therapist uptake and adoption of evidence-based treatment (Beidas & Kendall, 2010).

At the therapist level, uptake of evidence-based practice depends on the type of training received. Therapists can achieve significant knowledge gains from only attending a workshop, whether in person or web based. A large study (n = 67,201) documented that mental health professionals could reach proficiency in TF-CBT knowledge through taking the web-based course, TF-CBTWeb (Heck, Saunders, & Smith, 2015). However, studies that independently measured self-reported knowledge and therapist behavior documented that even when training led to knowledge proficiency, therapists’ skill levels were still far below the proficiency level (e.g., Beidas, Barmish, & Kendall, 2009; Gega, Norman, & Marks, 2007). In order to improve therapist skill in providing an evidence-based practice, training must include behavioral rehearsal with feedback and ongoing expert clinical consultation calls that address the therapists’ specific cases, in addition to workshop (Sholomskas, Syracuse-Siewert, Rounsaville, Ball, & Nuro, 2005). The “gold standard” for training in evidence-based treatment includes workshop, manual, and clinical consultation (Sholomskas et al, 2005).

Client variables include therapists’ belief that a particular evidence-based treatment can or cannot be effective for their clients; specifically, the common belief that research populations are not representative of the highly complex patients seen in usual care settings (Kendall & Beidas, 2007). In juvenile justice RTF settings, therapists must understand why a trauma-focused treatment should be used for their clients. In a research study context where informed consent/assent is required, the youth or their caregivers may refuse consent to participate in the research, adding another layer of complexity to understanding reasons for uptake failure.

Organizational barriers might include high staff attrition from the organization, increasing burden on the remaining therapists. Other organizational changes may also negatively impact therapists independent of the treatment they provide (e.g., increased case load, more paper work, etc.). As in child welfare, where many professionals work together to provide services to high need youth (Aarons & Palinkas, 2007), juvenile justice RTF includes administrators, teachers, and direct care staff members in addition to therapists, all of whom must understand and “buy-in” to the reason for using an evidence-based trauma treatment if it is to be optimally successful. Some juvenile justice RTF programs receive trauma-informed training of varying type, duration, and cost to inform staff about the impact of trauma (Ford et al., 2007), but these are distinct from evidence-based trauma treatment.

To support the successful implementation of TF-CBT in RTF settings, it is particularly important for RTF direct care staff to understand the relevance of trauma treatment and how to support the use of TF-CBT coping skills in the RTF milieu setting (Cohen, Mannarino, & Navarro, 2012). About half of adjudicated teens in RTF have significant PTSD symptoms and these may be an underlying cause of the youths’ severe behavioral and/or emotional dysregulation (Rosenberg et al., 2014). Many events in the RTF can serve as trauma reminders (e.g., stern adult voices can remind a traumatized teen of prior child abuse or domestic violence, arguing among peers can remind a traumatized teen of prior community or domestic violence, etc.). These trauma reminders often then “trigger” the youths’ trauma responses. In RTF settings, these trauma responses typically take the form of behavioral and/or emotional outbursts (Cohen, Mannarino, & Navarro, 2012). If direct care staff react to youth trauma responses in a manner that is oblivious to trauma impact (e.g., harshly redirecting the teen, confronting the teen in an authoritarian manner), this is likely to serve as an additional trauma reminder and lead to further teen dysregulation (trauma reenactment); it may also lead other traumatized youth to become dysregulated. Alternatively, if direct care staff react to youth trauma responses in a trauma-informed manner (e.g., remaining calm, acknowledging the reminder, validating the teen’s distress, and helping the teen use TF-CBT coping skills), this will likely help the youth to regain regulation instead of leading to trauma reenactment (Cohen, Mannarino, & Navarro, 2012).

The Current Study

The current study focused primarily on therapist challenges and uptake of TF-CBT. However, we also recognized the importance of organizational support for the use of traumafocused treatment as described above. In order to enhance RTF staff’s understanding and buy-in about the relevance of trauma treatment and to support the therapists’ use of TF-CBT in the RTF settings, a daylong integrated curriculum was developed on trauma-informed care for this project. Each module included interactive activities (e.g., role plays) and clinical vignettes. The modules were (1) trauma impact and reminders, (2) preventing trauma reenactment, (3) vicarious trauma, (4) TF-CBT skills, (5) supporting TF-CBT skills in RTF, and (6) TF-CBT skills and self-care. All administrators and staff at the participating RTF programs attended this training; each program received videotaped copies for subsequent staff review and discussion. Each module included specific objectives related to changes in knowledge, skills, and attitudes, but data were not collected in this regard for the current study.

The study focused on the therapists who would implement TF-CBT with traumatized adjudicated youth in their respective RTF programs. We hypothesized that RTF therapists would face three challenges in adopting TF-CBT for these youth, each of which would require a specific behavioral change (indicated in parenthesis): (1) do not see trauma as relevant (screen teens for trauma exposure and symptoms), (2) do not prioritize trauma in treatment (engage teens in TF-CBT treatment), and (3) other priorities or crises derail trauma treatment (complete TF-CBT with fidelity). The goal of the study was to evaluate two alternative TF-CBT workshop and consultation strategies to address these challenges and achieve these behavioral changes.

The Medical University of South Carolina has developed two free web-based products for TF-CBT training: the TF-CBTWeb online workshop and a free web-based consultation program for addressing common TF-CBT implementation challenges. Standard TF-CBT training requires therapists to complete TF-CBTWeb prior to attending a live workshop (https://tfcbt.org). Differences distinguishing the web-based resources from TF-CBT live workshops and phone consultation calls are that in the latter, therapists receive (1) behavioral rehearsal for specific TF-CBT skills, (2) positive feedback for specific actions indicating model fidelity, and (3) feedback on their own cases, all of which are associated with greater therapist changes in other evidence-based models. Examples of TFCBT strategies rehearsed during calls and their connection to hypothesized study outcomes included (1) assessing trauma impact (screening), (2) explaining the connection between trauma and current problems (engagement), and (3) applying specific TF-CBT components for teens in RTF (completion with fidelity).

Therapists were randomized within each participating RTF program to receive one of the two TF-CBT implementation and dissemination strategies, in order to evaluate the relative effectiveness of the respective strategies in addressing the above challenges and achieving TF-CBT uptake. These strategies were:

web-based TF-CBT dissemination (W): Therapists in the W strategy received the 10-hr online training course, TF-CBTWeb (www.musc.edu/tfcbt) which provided 10 free CE credits and were encouraged to access the free online consultation course, TF-CBTWebConsult (www.musc.edu/tfcbtconsult), as needed.

W + Live TF-CBT dissemination (W + L): Therapists in the W + L strategy received the above W strategy and also received a 2-day, face-to-face TF-CBT workshop plus 12 months of twice-monthly TF-CBT phone expert TF-CBT consultation calls with behavioral rehearsal of specific behaviors that met TF-CBT fidelity and positive feedback for these behaviors that applied to the therapists’ own RTF cases.

Since the W + L condition included elements associated with superior therapist uptake of evidence-based treatment, we hypothesized that the W + L strategy would be superior to the W strategy for effecting therapist change. Specifically, we hypothesized that:

-

1

W + L therapists would screen significantly more youth for trauma exposure and trauma symptoms than W therapists (screening was defined by the youth completing the online study screening instrument),

-

2

W + L therapists would engage significantly more youth in TF-CBT treatment than W therapists (treatment engagement was defined by the youth completing the initial study assessment instruments, study assent, and at least one TF-CBT treatment session),

-

3

W + L therapists would complete TF-CBT with significantly more youth than W therapists (study completion was defined by therapist determining that treatment was completed and the youth completing posttreatment assessment instruments), and

-

4

W + L therapists would demonstrate significantly higher TF-CBT fidelity than W therapists (fidelity was defined by therapist providing 8–30 sessions of TF-CBT and appropriate order of treatment components, described in detail below).

Additionally, we hypothesized that:

-

5

Across therapist conditions, adjudicated teens completing TF-CBT would experience significant improvement in PTSD and depressive symptoms. (Externalizing behavioral problems would have been an outcome of great interest as well but unfortunately it was not feasible to collect these data in the current study).

Method

Participants

RTF programs

Eighteen RTF programs in three New England states participated in the project. All RTF programs served adjudicated youth aged 12–17 years and none were currently implementing an evidence-based trauma-focused therapy. None had received formal trauma-informed training prior to the start of the project. Requirements for participating RTF programs were (1) serving adjudicated youth aged 12–17 years, (2) employing two or more mental health therapists who provided ongoing treatment to youth in the RTF, and (3) RTF leadership agreed to participate in the project and signed Federal Wide Assurance for protection of human subjects. The study was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health and was conducted between November 2011 and November 2014. The study was approved by the institutional review boards (IRBs) of Allegheny General Hospital, Dartmouth College, and the Connecticut Department of Children and Families (DCF). Since the participating RTF programs did not have independent IRBs, the Dartmouth College IRB served as the responsible IRB for the New Hampshire and Vermont RTF programs and the Connecticut DCF IRB served as the responsible IRB for the Connecticut RTF programs.

Therapists

Mental health therapists who provided ongoing individual therapy to adjudicated youth at the participating RTF programs were eligible to participate in the project. Administrators at the respective RTF programs determined whether all therapists in the RTF or only those in specific units would participate in the project based on programmatic priorities. Within any given unit or program that was included in the project, all therapists had the option to participate. Both licensed and unlicensed therapists provided therapy to adjudicated youth in these settings, and thus both types of therapists participated in the study.

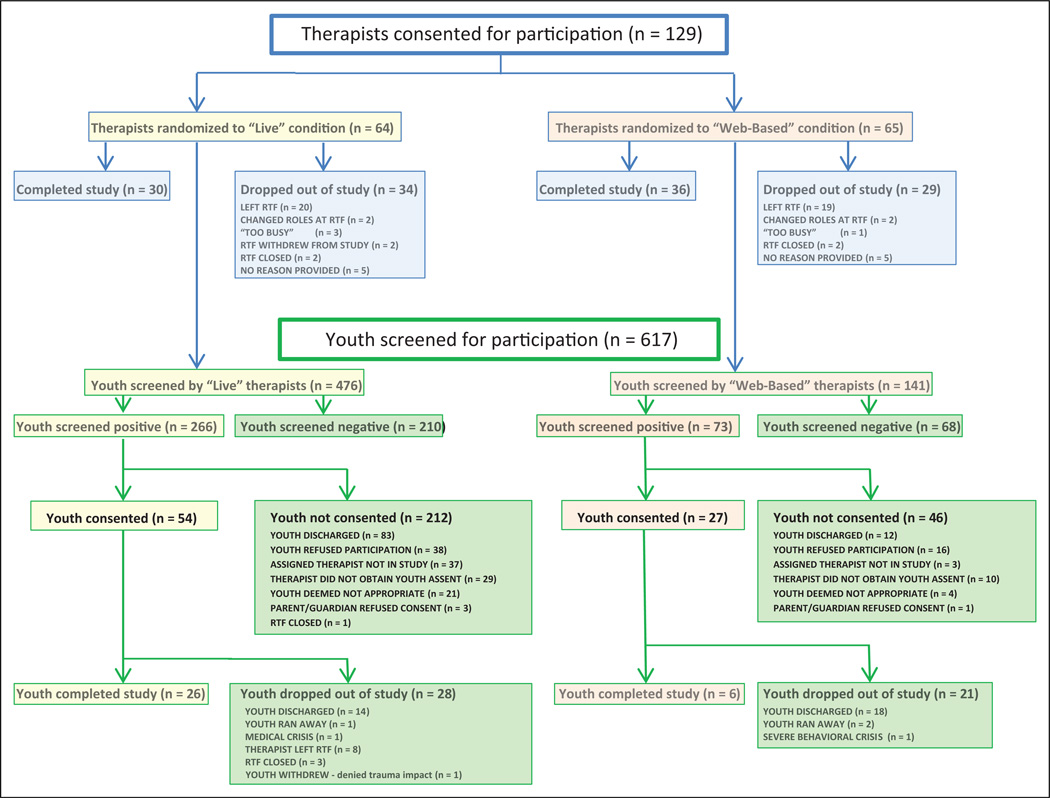

One hundred twenty-nine therapists consented to participate in the study. Of these, 63 (48.8%) dropped out during the course of the project. Reasons for dropping out included the following: therapist left the RTF (n = 39), therapist’s role in the RTF changed (n = 4), therapist was too busy to participate (n = 4), RTF closed (n = 4), and RTF program withdrew from the project (n = 2). Ten additional therapists dropped out without providing a reason. Therapist dropouts did not differ significantly between the two groups. Therapist demographics are provided in Table 1. A Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flowchart is provided in Figure 1.

Table 1.

Therapist and Youth Demographics.

| Therapist Demographics | Web Therapists (n = 65) |

Web + Live Therapists (n = 64) |

|---|---|---|

| Male n (%) | 14 (21.5) | 11 (17.2) |

| Female n (%) | 51 (78.5) | 53 (82.8) |

| Age mean (SD) | 40.4 (11.9) | 38.1 (12.2) |

| Caucasian n (%) | 57 (89.1) | 59 (90.8) |

| Black (%) | 4 (6.3) | 4 (6.2) |

| American Indian (%) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.5) |

| Pacific Islander (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Asian (%) | 2 (3.1) | 1 (1.5) |

| Unreported (%) | 1 (1.5) | 0 (0) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 3 (4.7) | 3 (4.6) |

| Education and licensure | ||

| Licensed social workers N (%) | 17 (26.2) | 15 (23.4) |

| Licensed mental health counselors |

14 (21.5) | 14 (21.9) |

| Other licensed therapists | 4 (6.2) | 7 (10.9) |

| Unlicensed therapists | 30 (46.1) | 28 (43.8) |

| Experience | ||

| 0–5 years (%) | 20 (30.8) | 27 (42.2) |

| 5–10 years | 22 (33.8) | 17 (26.5) |

| 10–15 years | 13 (20.0) | 6 (9.4) |

| >15 years | 10 (15.4) | 14 (21.9) |

| Youth demographics | Web Youth (n = 27) |

Web + Live Youth (n = 54) |

| Male n (%) | 12 (44.4) | 27 (50) |

| Female n (%) | 15 (55.6) | 27 (50) |

| Age years (SD) | 15.2 (1.4) | 15.0 (1.5) |

| Caucasian n (%) | 17 (63) | 33 (61.1) |

| Black (%) | 4 (14.8) | 2 (3.7) |

| American Indian (%) | 0 (0) | 4 (7.4) |

| Pacific Islander (%) | 1 (3.7) | 2 (3.7) |

| Asian (%) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.9) |

| Unreported (%) | 5 (18.5) | 12 (22.2) |

| Hispanic/Latino (%) | 1 (3.7) | 6 (11.1) |

| # Of trauma types | 6.1 (2.7) | 6.9 (2.3) |

Figure 1.

Flowchart: Participants.

Youth

Adjudicated youth aged 12–17 years who were residing at participating RTF programs were eligible to be screened for the project. According to IRB definitions, adjudicated youth qualified as both children and prisoners and thus received heightened IRB safeguards to assure appropriate protection of human subjects. From the perspective of therapists providing treatment in the RTF setting, this substantially complicated the usual process of introducing and initiating mental health treatment. This process involved the following steps: (1) Youth who agreed to trauma screening were screened for trauma exposure and trauma symptoms by their assigned therapist during the RTF’s usual intake procedures. (2) Youth were eligible to participate in the study if they (a) reported having at least one trauma experience on the University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA) PTSD Reaction Index (RI), (b) scored ≥22 on the RI corresponding to moderately severe PTSD symptoms (Steinberg, Brymer, Decker, & Pynoos, 2004), and (c) would continue to be treated by a study therapist. (3) If a youth was eligible to participate, the therapist requested the youth’s permission to provide the parent’s contact information to the research coordinator. Therapists could choose not to approach the youth for permission or could determine that youth were not appropriate to participate based on clinical judgment or youth could refuse permission to contacting parent. (4) If the youth agreed, the research coordinator contacted the parent to describe the study and obtain written parental consent for the youth’s participation in the study. (5) If parental consent was obtained, the research coordinator described the study in detail to the youth and obtained youth written assent as well. Youth received a US$20 Amazon gift certificate for completing the online posttreatment assessment instruments.

Of the 617 youth who were screened during the study, 562 (91%) screened positive for trauma exposure and 339 (54.9%) screened positive for both trauma exposure and symptoms on the RI. Of these, 258 (76%) did not participate in the study. Reasons for not participating included the following: youth were discharged from RTF too soon to begin treatment (n = 95; this typically occurred due to a new court hearing resulting in adjudication to a less restrictive setting outside the RTF), youth refused to participate in the study (n = 54), youth were reassigned to a nonstudy therapist (n = 40; most typically due to therapist leaving the program), therapist failed to request permission to contact parents/legal guardians (n = 39), therapist determined that youth were inappropriate to participate in the study (n = 25), parent/legal guardian refused to consent (n = 4), or RTF program closed after youth screened positive (n = 1). Eighty-one youth and their parents/guardians assented/consented to participate in the study. Demographics of consenting youth are provided in Table 1. A CONSORT flowchart is provided in Figure 1.

Instruments

Therapists completed instruments at the start of the study to assure equivalence between groups on use of cognitive and behavioral models, computer use, and TF-CBT knowledge. Therapists completed a fidelity checklist (FC) after each TF-CBT treatment session. Youth completed online pre- and posttreatment self-report measures of PTSD and depression.

Therapist Instruments

Therapy procedure checklist (TPC)

The TPC is a 62-item therapist self-report measure scored on a 5-point Likert-type scale (1–5) that assesses therapists’ use of and comfort with child cognitive, behavioral, psychodynamic, and family treatment models (range = 62–310; Weersing, Weisz, & Donenberg, 2002). The cognitive scale has 15 items (range = 15–75). The TPC has high internal consistency (α = .9–.94) and test–retest reliability (.86–.94) for each of the four subscales (cognitive, behavioral, psychodynamic, and family).

Attitudes Toward Computer Usage Scale (ATCUS), Version 2.0

The ATCUS is a 22-item self-report instrument that assesses adult attitudes and comfort with computer use on a 7-point Likert-type scale (range = 0–132; Morris, Gullekson, Morse, & Popovitch, 2009). The ATCUS has high internal consistency (α = .83) and test–retest reliability (.93).

TF-CBT knowledge test (KT)

The TF-CBT KT is a 40-item therapist-completed test that assesses knowledge about TF-CBT (Heck et al., 2015). Each question has a single correct answer; the score indicates the number of correct answers. The test has strong psychometric properties and learners gain significant knowledge from pre- to posttest, with most effect sizes falling in the medium or large range after completing TF-CBTWeb online.

TF-CBT FC

The FC is a 9-item checklist that lists the nine TF-CBT treatment components; immediately after each treatment session, the therapist checks which component(s) were delivered during that treatment session. A previous study in which community therapists provided TF-CBT and self-rated their own treatment sessions using the FC (Cohen, Mannarino & Iyengar, 2011) found high inter-rater reliability (.92) between therapists’ self-ratings of their own sessions and expert ratings of those audiotaped sessions. For the current study, a composite FC score of 0–2 was derived for each TF-CBT case with a score of 2 required to meet required fidelity standards. Points were allotted for (1) treatment length (8–30 sessions = 1 point) and (2) all PRACTICE components were provided in appropriate order = 1 point. For noncompleters, fidelity was rated based on the provided components; if at least eight sessions were provided and all components were provided in the appropriate order, the case received 2 points and met fidelity standards.

Youth Instruments

The UCLA PTSD RI for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition (DSM-IV), Adolescent Version (RI; Steinberg et al., 2004) is a 22-item self-report instrument to assess DSM-IV PTSD symptoms (range = 0–88). This version also includes 13 items to assess trauma exposure. It has high reliability and validity including when completed online (Steinberg et al., 2004). A cutoff score of ≥22 (moderately severe PTSD) was required for inclusion in the study. A score of ≥38 is correlated with full PTSD diagnosis.

The Mood and Feelings Questionnaire–Short Version (MFQ) is a 13-item brief version (range = 0–26) of the longer MFQ, a self-report instrument to assess youth depression. It has high reliability and validity including when used with adjudicated adolescents (Kuo, Vander Stoep, & Steward, 2005). A cutoff score of >10 is associated with depression in this population (Kuo et al., 2005).

Procedures

An investigator explained the study to therapists at the participating programs and answered questions about the research project. Therapists were given the option to consent or not. Consenting therapists received training in study screening and data entry procedures and were randomized to study conditions through the use of sealed envelopes. The design was double blinded (youth and research coordinator were blind to therapists’ training condition). Therapists in both conditions received information about the W training and consultation websites. Two-day, face-to-face TF-CBT training was scheduled within 1 month of consent for the W + L therapists; W + L therapists then received 12 months of twice-monthly TF-CBT consultation calls focusing on implementing TF-CBT for the participants’ RTF treatment cases. TF-CBT was provided in these RTF settings as described above, that is, all components except in vivo mastery were done in completed cases (Cohen, Mannarino, & Navarro, 2012).

In order to prevent contamination across conditions, therapists received supervision only by supervisors in their own condition and were instructed to not discuss TF-CBT implementation strategies or share TF-CBT implementation resources with therapists in the other dissemination condition during the course of the study. Regular checks were conducted to assure that cross-contamination between dissemination conditions was not occurring within RTF site.

Therapists in two states received US$10 Amazon gift cards for completing 10 online youth trauma screens and a US$20 Amazon gift card for the additional time involved in assisting youth to obtain computer access in order to complete posttreatment assessment instruments. Therapists in the third state were not allowed to receive gift cards due to being state employees. Instead, they received therapy books, games, or videos of their choice in lieu of gift cards.

Power analysis

Therapists were randomly assigned to W versus W + L, with youth nested within therapists. The primary study hypotheses referred to the therapists’ performance (e.g., probability of screening for PTSD, engaging youth in and completing TF-CBT treatment, and average TF-CBT fidelity). Assuming an average therapist attrition of 40%, we estimated that we would need to recruit ~65 therapists per group in order to achieve 80% power between the W and W + L therapist analyses.

Data Collection and Analyses

Data from therapists and youth were collected and entered via a secure online dashboard. Therapists received training in accessing and entering data using the dashboard at the start of the study. Each therapist received a unique identifying number and password to access the dashboard. After each TF-CBT treatment session with a participating youth, the therapist completed an FC using unique identifiers for therapist and treatment case.

Participating youth were assigned unique identifying numbers. Due to the nature of the population and setting (youth did not have unsupervised computer access in the RTF settings), therapists assisted youth in accessing the dashboard at pre- and posttreatment and the youth completed the study instruments privately, as permitted by individual RTF policies.

Outcomes included comparisons of W versus W + L therapists with regard to (1) number of youth screened for trauma exposure and impact, (2) number of youth beginning TFCBT treatment after project consent/assent, (3) number of youth completing TF-CBT, and (4) TF-CBT fidelity. Youth improvement in PTSD and depressive symptoms after TFCBT treatment was also analyzed. Finally, impact of therapist characteristics (education, licensure, and years of experience) was examined.

Since the distribution of screening data was so skewed and had so many 0s, a nonparametric Wilcoxon test was used. A χ2 test was also conducted in order to compare differences between having conducted any screens (coded as 1) and no screens (coded as 0). Treatment engagement was analyzed using a t-test. Treatment completion was analyzed using a t-test and χ2 with Yates correction. Youth completer outcomes were analyzed using t-tests. χ2 analyses were used to examine therapist characteristics and their impact of implementation outcomes. Anecdotal information about implementation challenges was noted by expert consultants during W + L consultation calls, as these arose during the calls. These were compiled during monthly research meetings and at the end of the study, but consultation calls were not recorded and content was not examined in a systematic manner.

Results

No significant differences were found at the start of the study between the W and W + L groups with regard to therapist demographic characteristics (gender, race, ethnicity, education, licensure, or years of experience; Table 1) or on the TPC, ATCUS, or KT (Table 2). No significant differences were found at the start of the study between conditions with regard to youth demographic characteristics (gender, age, race, ethnicity, or number of trauma types; Table 1) or on the RI or MFQ (Table 2).

Table 2.

Pretreatment Measures.

| Measures | Web Therapists (n = 65) Mean (SD) |

Web + Live Therapists (n = 64) Mean (SD) |

t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATCUS | 88.0 (10.0) | 88.9 (9.2) | .54 | .59 |

| KT | 26.4 (4.2) | 25.3 (4.6) | .95 | .34 |

| TPC (total) | 215.9 (31.8) | 213.2 (34.4) | .64 | .52 |

| TPC (cognitive subscale) | 56.9 (9.2) | 57.4 (8.9) | .31 | .75 |

| Youth (n = 27) | Youth (n = 54) | |||

| UCLA-RI (total) | 45.8 (18.8) | 46.4 (15.9) | .14 | .89 |

| MFQ | 11.9 (6.9) | 11.1 (7.1) | .38 | .71 |

Note. ATCUS = Attitudes Toward Computer Usage Scale, 2.0; KT = traumafocused cognitive behavioral therapy knowledge test; MFQ = Mood and Feelings Questionnaire-Short Version; TPC = therapy procedure checklist; UCLARI = University of California at Los Angeles post-traumatic stress disorder Reaction Index for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition.

Screening

As shown in Table 3, significantly more W + L therapists than W therapists conducted screening (W = 2,712.5). Half of the W + L therapists in the study conducted at least one screen while most of the W therapists conducted no screens; this difference was also significant (χ2 = 11.49, p = .0007).

Table 3.

Results Therapist TF-CBT Uptake by Implementation Group.

| Web | Web + Live | Test | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Screening, n (%) | 142 (23) | 475 (77) | ||

| Mean screens/therapist | 2.18 | 7.42 | W = 2,712.5 | .0005 |

| % Therapists conducting >1 screen | 20 | 50 | χ2 = 11.49 | 0.0007 |

| Engagement, n (%) | 27 (33) | 54 (67) | ||

| # Engaged/therapist | 0.41 | 0.84 | t = 1.54 | 0.13 |

| Completion, n (%) | 6 (18.75) | 26 (81.25) | ||

| # Therapists completing | 3 | 13 | t = 2.18 | 0.031 |

| Youth completion rate | 22% | 48% | χ2 = 5.06 | 0.045 |

| Fidelity | ||||

| # (%) Among engaged | 5 (18.5) | 30 (55.6) | χ2 = 10.06 | 0.0015 |

| # (%) Among completers | 5 (83) | 25 (96) | = 1.37 | 0.24 |

| Impact of therapist characteristics | χ2 | p | Comments | |

| Screening | Educationa | 2.60 | .27 | |

| Experience | 0.18 | .66 | ||

| Licensure | 3.85 | .04 | W only: p = .18; W + L: p = .0007 | |

| Engagement | Education | 3.36 | .18 | |

| Experience | 0.079 | .77 | ||

| Licensure | 4.51 | .03 | W only: p = .18; W + L only: p = .0003 | |

| Completion | Education | 2.75 | .25 | |

| Experience | 0.17 | .67 | ||

| Licensure | 2.79 | .09 | W only: p = .46; W + L only: p = .01 | |

| Fidelity | Education | 1.94 | .37 | |

| Experience | 0.14 | .70 | ||

| Licensure | 5.07 | .02 | W only: p = .87; W + L only: p = .006 | |

| Youth completer outcomes | ||||

| n = 32 | pretreatment | posttreatment | t | p |

| RI mean (SD) | 51.5 (18.7) | 37.0 (16.8) | 5.16 | .001 |

| MFQ mean (SD) | 12.9 (7.4) | 8.5 (6.7) | 2.65 | .018 |

Note. MFQ = Mood and Feelings Questionnaire-Short Version (clinical cutoff = 10); RI = University of California at Los Angeles post-traumatic stress disorder Reaction Index (clinical cutoff = 38); TF-CBT = trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy.

Impact of education on outcomes only included therapists who were licensed as only licensed therapists provided sufficient data on educational background.

Treatment Engagement

W + L therapists engaged more than twice as many youth as W therapists in TF-CBT treatment, but this was not statistically significant as shown in Table 3. There was large variation in the number of treatment sessions provided by W therapists (range = 1–40 sessions, mean = 9.1 sessions) and W + L therapists (range = 1–33 sessions, mean = 11.2 sessions).

Completing TF-CBT

As shown in Table 3, significantly more youth treated by W + L therapists completed treatment than youth treated by W therapists, after controlling for therapist effect. Youth receiving treatment from W + L therapists were significantly more likely to complete treatment than those receiving treatment from W therapists (χ2 = 5.06, p = .045).

TF-CBT Fidelity

As shown in Table 3, a significantly higher proportion of teens treated by W + L therapists received TF-CBT with fidelity than those treated by W therapists (χ2 = 10.06, p = .00015). However, among treatment completers, no significant differences between the W and W + L groups were found.

Youth Outcomes

Adjudicated teens in RTF who completed TF-CBT experienced statistically and clinically significant improvement in PTSD (t = 5.16, p < .0001) and depressive (t = 2.65, p < .018) symptoms from pre- to posttreatment as shown in Table 3.

Impact of Therapist Characteristics on Outcomes

Therapists’ education and years of experience did not significantly impact implementation outcomes. Licensed therapists were significantly more likely than nonlicensed therapists to screen (χ2 = 3.85, p < .04), to engage youth in TF-CBT (χ2 = 4.51, p < .03), and to complete TF-CBT with fidelity (χ2 = 5.07, p < .02; Table 3), with a trend for licensure to significantly impact TF-CBT completion. As shown in Table 3, when conditions were examined separately, the impact of licensure was only significant within the W + L group.

Discussion

This study evaluated two different implementation strategies, W versus W + L, for increasing therapist uptake of an evidence-based youth trauma treatment, TF-CBT, for adjudicated teens in RTF settings. The W + L strategy was superior to the W strategy regarding therapists successfully completing trauma screening, completing TF-CBT treatment, and providing TF-CBT with fidelity. Despite the increased availability and reach of online training programs such as TF-CBTWeb, this study tends to support previous research which indicates that face-to-face workshop and expert ongoing consultation promote more optimal implementation of evidence-based treatment in clinical practice (Beidas & Kendall, 2010). This may be particularly true in highly challenging clinical settings such as RTF for adjudicated teens.

Another important finding was that TF-CBT could be successfully implemented for adjudicated teens in RTF who had a high number of different trauma types. This is consistent with other studies that have documented the efficacy of TF-CBT for treating multiply traumatized youth in other settings (e.g., McMullen et al., 2013; O’Callaghan et al., 2013) and lends further support for the effectiveness of TF-CBT for treating youth who have complex trauma (Cohen, Mannarino, Kleithermes & Murray, 2012). Although improvement was highly significant and mean scores moved from the very severe to moderate PTSD levels, improvement in PTSD scores was modest compared to previous studies, and 37%continued to have scores consistent with full PTSD. This may be due to differences in assessment strategies (self-report vs. blinded evaluators), different settings (adjudicated youth in RTF vs. outpatient settings), differences between randomized controlled treatment studies and less controlled conditions inherent in implementation/dissemination studies, or all of the above.

Of the three changes therapists were asked to make in this project, trauma screening was most successfully implemented. Screening takes relatively little time and in contrast to the other activities in the project, it did not require obtaining research consent from parents or teens. Nonetheless, more than half of the therapists screened no youth during the project. This was particularly true for W therapists, of whom 80%failed to screen any youth. The W therapists may have perceived project participation as an additional burden; and without the benefit of live training or consultation calls, they were unwilling to take this on. In contrast, during W + L consultation calls, consultants actively encouraged therapists to screen youth, which may have influenced some W + L therapists to conduct screenings.

W + L therapists were significantly more likely to retain youth in TF-CBT. A possible explanation for this difference is that the consultation calls provided repeated behavioral rehearsal and positive feedback for addressing clinical challenges that arose during treatment and discussed their specific clients and challenges encountered with implementing TFCBT with these cases—all elements that have been shown to enhance uptake of evidence-based treatment (Sholomskas et al., 2005). Despite this, dropouts in both conditions were far higher than in previous TF-CBT efficacy studies (Cohen et al., 2004; Cohen, Mannarino & Iyengar, 2011) and in a previous RTF effectiveness study for traumatized youth (e.g., Ahrens & Rexford, 2012).

The most difficult change for study therapists to make was engaging youth in the study. Consistent with current literature on research in the juvenile justice system, barriers occurred at the youth, therapist, and organizational/systemic levels (Lane, Goldstein, Heilbrun, Cruise, & Pennacchia, 2012; Wolbransky, Goldsetin, Giallella, & Heilbrun, 2013). At the youth level, adjudicated youth, particularly in juvenile justice settings, are likely to distrust professionals and “the system” and to be concerned that anything they say, including during treatment, may be used against them (e.g., in legal or placement proceedings). A substantial proportion refused participation, with two youth refusing for every three who assented. This is a much higher refusal rate than we have encountered in other TF-CBT study settings, where the majority of traumatized youth agree to participate in treatment research. Refusing to participate in the research project may have provided adjudicated youth with a rare instance in which they could assert their free will in the RTF, since all other treatment they received in RTF was involuntary. However, since informed consent was required for participation, it is also possible that the barrier was obtaining consent for research, rather than engaging youth in trauma treatment per se. It is possible that many more youth would have agreed to receive TF-CBT treatment had they not been required to sign informed assent to participate in research.

Several barriers to starting TF-CBT occurred at the therapist level. Many therapists did not start TF-CBT based on their clinical judgment, despite screening indicating that the youth may have benefited from this treatment. The study design did not allow us to determine specific reasons for these clinical judgments, but one explanation that is sometimes heard in this regard in residential treatment settings is that the youth is “not ready” to address trauma issues (Cohen, Mannarino & Navarro, 2012). This is sometimes an indication of therapist (rather than youth) trauma avoidance (Cohen, Mannarino & Navarro, 2012). Specifically, therapists may avoid beginning trauma treatment because it is easier and less painful to focus on the youth’s behavioral problems than to directly engage the youth in therapeutic exploration about his or her multiple trauma experiences. Other possible explanations are that the therapists did not believe that trauma was the primary problem that needed to be addressed for the youth at that time (e.g., that other mental health problems were more pressing) and/or that the youth did not have significant trauma issues that needed to be addressed in treatment. Other therapist issues such as lack of time, feeling pressured, overwhelmed, or overburdened may have also contributed to therapist decisions not to begin TFCBT treatment, since participating in the study was optional and took additional time and effort.

The findings that therapist licensure significantly impacted implementation outcomes, and specifically that licensure differentially impacted implementation outcomes for W + L therapists, suggest that licensed therapists differentially benefit from the W + L implementation strategy. Since providing therapy under structured supervision is required for mental health licensure, it is likely that the W + L format was more familiar to and congruent with the training expectations of licensed therapists than those who were not licensed. Licensed therapists thus may have been more willing than unlicensed therapists to attend W + L consultation calls, participate in behavioral rehearsal, be receptive to expert feedback, and implement the required changes in order to provide the TF-CBT model to successful completion. Therapist licensure is currently required in order to receive national TF-CBT certification (https://tfcbt.org) and these results tend to support that standard.

Organizational and systemic barriers also discouraged therapists from starting TF-CBT. During the course of the study, RTF programs in New England underwent substantial transformation leading to fewer RTF beds concentrated in larger, more centralized programs. Two RTF programs in the study closed completely; two others were condensed into one program and another RTF program withdrew from the project due to internal issues. Programmatic cuts and changes occurred in several other programs, resulting in changes in therapist positions and increased therapist responsibilities as well as unpredictability and anxiety for staff and large staff turnover. For example, several therapists were given the option of taking TF-CBT cases in addition to their usual treatment caseload, if they chose to treat youth in the study. Since TF-CBT treatment entailed extra, optional work that was not incentivized, it is understandable that these therapists engaged few youth in the study. In light of the above changes, administrative priorities shifted from focusing on adopting new programs such as trauma treatment to simply assuring that their programs remained open. Organizational change literature demonstrates that innovation is nearly impossible when an organization is confronted with so many threats to its basic existence. When this is the case, all attention goes toward basic survival of the organization (Drabble, Jones, & Brown, 2013). Unfortunately, given the prevalence of these conditions for such programs, administrative enthusiasm for the project, which had been strong at the start of the research project, declined considerably over time.

These experiences strongly underscore the critical importance of organizational readiness when undertaking implementation of evidence-based trauma treatment, particularly when working with systems that traditionally do not focus on trauma, such as the juvenile justice system in which these RTF programs functioned. In these settings, the National Child Traumatic Stress Network’s learning collaborative methodology (Markiewicz, Ebert, Ling, Amaya-Jackson, & Kisiel, 2006) in which organizations are carefully screened for organizational commitment, and senior leaders and supervisors as well as therapists are integrally involved in learning and implementing changes, may be an optimal approach for embedding lasting TF-CBT uptake.

The three W therapists who completed TF-CBT cases met expected fidelity standards in 83% of their treatment cases, demonstrating that some therapists can learn to provide TFCBT with fidelity and achieve positive outcomes without face-to-face training and consultation calls. This underscores the value of the TF-CBTWeb course and TF-CBTWebConsult program to the thousands of therapists, particularly those outside the United States, who do not have ready access to live workshops and ongoing consultation. The TF-CBTWeb course alone currently has more than 220,000 registrants in over 120 countries, a testament to its accessibility and popularity. For motivated therapists, these products provide a vital resource for evidence-based trauma training and have the potential to lead to successful uptake.

Limitations

The inability to assess youth externalizing behavior problems was a limitation of the study and may have contributed in part to low therapist participation and retention in the study. Another limitation was the failure to collect data about changes in knowledge, skills, and attitudes following the trauma-informed care curriculum training, which may have provided valuable information about problems with organizational buy-in that could have been addressed earlier in the study. Other limitations included relying solely on therapists’ self-report for fidelity rather than obtaining independent ratings of audiotaped treatment sessions, and the lack of audiotaping and systematic rating of data obtained from W + L consultation calls that could have helped to better identify implementation challenges. Another limitation is that the study design did not allow us to determine whether the face-to-face training, consultation calls, or both were responsible for the superior outcomes of the W + L group. Therapist dropout, youth refusal, and youth dropout during treatment were all quite high during the study as described above. These factors may have led to the therapists and/or youth who ended up participating or completing the study being unrepresentative of the overall population and thus skewing results.

Future Research

Future studies should study changes in knowledge, skills, and attitudes following the trauma-informed curriculum training, how this affects buy-in among different RTF administrators and staff, and whether this in turn impacts TF-CBT uptake among therapists. It also would be valuable to compare the relative effectiveness of the W versus W + L strategies within other trauma-informed child serving systems, such as child welfare or in outpatient juvenile justice settings. It is probably not surprising that offering more support in the form of face-to-face training and ongoing consultation improves implementation outcomes. In a time of diminishing resources, it is not only important to understand what works, but how much it costs, whether the less expensive alternative is “good enough,” and whether the incremental improvements between two implementation alternatives are worth the additional expenditure. Future research should explicitly focus on cost-effectiveness analyses in this regard. Finally, as evidence-based practices continue to spread, more research should focus on what therapist qualifications (e.g., licensure) and implementation strategies can provide good enough trauma treatment to the thousands of youth who desperately need it.

Acknowledgments

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was funded by the National Institute for Mental Health, Grant No. R01 MH095208. We thank the RTF administrators, therapists, youth, families and research staff who participated in the project.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Aarons GA, Palinkas LA. Implementation of evidence-based practice in child welfare: Service provider perspectives. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2007;34:411–419. doi: 10.1007/s10488-007-0121-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahrens H, Rexford L. Cognitive processing therapy for incarcerated adolescents with PTSD. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment and Trauma. 2012;6:201–216. [Google Scholar]

- Beidas RS, Barmish AJ, Kendall PC. Training as usual: Can therapist behavior change after reading a manual and attending a brief workshop on cognitive behavioral therapy for youth anxiety? The Behavior Therapist. 2009;32:97–101. [Google Scholar]

- Beidas RS, Kendall PC. Training therapists in evidence-based practice: A critical review of studies from a systems-contextual perspective. Clinical Psychology. 2010;17:1–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2850.2009.01187.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen JA, Deblinger E, Mannarino AP, Steer R. A multisite, randomized controlled trial for children with sexual abuse-related PTSD symptoms. Journal of the American Academy Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2004;43:393–402. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200404000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen JA, Mannarino AP, Deblinger E. Treating trauma and traumatic grief in children and adolescents. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen JA, Mannarino AP, Iyengar S. Community treatment of PTSD for children exposed to intimate partner violence: A randomized controlled trial. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 2011;165:16–21. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen JA, Mannarino AP, Kliethermes M, Murray LA. Trauma-focused CBT for youth with complex trauma. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2012;36:528–541. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2012.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen JA, Mannarino AP, Murray LA. Trauma-focused CBT for youth with ongoing trauma. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2011;35:637–646. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2011.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen JA, Mannarino AP, Navarro D. Residential treatment. In: Cohen JA, Mannarino AP, Deblinger E, editors. Trauma-focused CBT for children and adolescents: Treatment applications. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2012. pp. 73–104. [Google Scholar]

- Currie J, Tekin E. Does child abuse cause crime? NBER Working Paper No. 12171. 2006 Retrieved from http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=897025. [Google Scholar]

- Drabble L, Jones S, Brown V. Advancing trauma-informed systems change in a family drug treatment court context. Journal of Social Work Practice in the Addictions. 2013;13:91–113. [Google Scholar]

- Fixsen DL, Naoom SF, Blasé KA, Friedman RM, Wallace F. Implementation research: A synthesis of the literature. Tampa: University of South Florida; 2005. (Louis de la Parte Mental Health Institute Publication # 231) [Google Scholar]

- Ford JD, Chapman JF, Hawke J, Albert D. Trauma among youth in the juvenile justice system: Critical issues and new directions. Washington, DC: National Center for Mental Health and Juvenile Justice Research; 2007. Retrieved from http://www.ncmhjj.com/pdfs/Trauma_and_Youth.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Gega L, Normal I, Marks I. Computer-aided vs. tutor-delivered teaching of exposure therapy for phobia/panic: randomized controlled trial with pre-registration nursing students. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2007;44:397–405. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2006.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heck NC, Saunders BE, Smith DW. Web-based training for an evidence-supported treatment: Training completion and knowledge acquisition in a global sample of learners. Child Maltreatment. 2015;20:183–192. doi: 10.1177/1077559515586569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall PC, Beidas RS. Smoothing the trail for dissemination of evidence-based practices for youth: Flexibility within fidelity. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2007;38:13–20. [Google Scholar]

- Kuo ES, Vander Stoep A, Steward DS. Using the short mood and feelings questionnaire to detect depression in detained adolescents. Assessment. 2005;12:374–385. doi: 10.1177/1073191105279984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane C, Goldstein N, Heilbrun K, Cruise K, Pennacchia D. Obstacles to research in residential juvenile justice facilities: Recommendations for Researchers. Behavioral Sciences and the Law. 2012;30:49–86. doi: 10.1002/bsl.1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mannarino AP, Cohen JA. Trauma focused cognitive behavioral therapy. In: Timmer S, Urquiza A, editors. Evidence-based approaches for the treatment of maltreated children. New York, NY: Springer Press; 2014. pp. 165–185. [Google Scholar]

- Markiewicz J, Ebert L, Ling D, Amaya-Jackson L, Kisiel C. Learning collaborative toolkit. Los Angeles, CA: National Center for Child Traumatic Stress; 2006. Retrieved from http://www.nctsn.org/resources/learning-collaborative-toolkit%20. [Google Scholar]

- McMullen J, O’Callaghan P, Shannon C, Black A, Eakin J. Group trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy with former child soldiers and other war-affected boys in the DR Congo: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Child Psychology Psychiatry. 2013;54:1231–1241. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris SA, Gullekson NL, Morse BJ, Popovitch PM. Updating the attitudes towards computer usage scale using American undergraduates. Computer in Human Behavior. 2009;25:535–543. [Google Scholar]

- O’Callaghan P, McMullen J, Shannon C, Rafferty H, Black A. A randomized controlled trial of trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy for sexually exploited, war exposed Congolese girls. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2013;52:359–369. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2013.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg HJ, Vance JE, Rosenberg SP, Wolford GL, Ashley SW, Howard ML. Trauma exposure, psychiatric disorders and resiliency in juvenile justice involved youth. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice and Policy. 2014;6:430–437. [Google Scholar]

- Sholomskas DE, Syracuse-Siewert G, Rounsaville BJ, Ball SA, Nuro KF. We don’t train in vain: A dissemination trial of three strategies of training in cognitive behavioral therapy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73:106–115. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.1.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg AM, Brymer MJ, Decker KB, Pynoos RS. The University of California at Los Angeles PTSD reaction index. Current Psychiatry Reports. 2004;6:96–100. doi: 10.1007/s11920-004-0048-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weersing VR, Weisz JR, Donenberg GR. Development of the therapy procedures checklist: A therapist-report measure of technique use in child and adolescent treatment. Journal of Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2002;31:168–180. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3102_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolbransky M, Goldsetin N, Giallella C, Heilbrun K. Collecting informed consent with juvenile justice populations: Issues and implications for research. Behavioral Sciences and the Law. 2013;31:457–476. doi: 10.1002/bsl.2068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]