Abstract

The production of interleukin-12 (IL-12) is critical to the development of innate and adaptive immune responses required for the control of intracellular pathogens. Many microbial products signal through Toll-like receptors (TLR) and activate NF-κB family members that are required for the production of IL-12. Recent studies suggest that components of the TLR pathway are required for the production of IL-12 in response to the parasite Toxoplasma gondii; however, the production of IL-12 in response to this parasite is independent of NF-κB activation. The adaptor molecule TRAF6 is involved in TLR signaling pathways and associates with serine/threonine kinases involved in the activation of both NF-κB and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK). To elucidate the intracellular signaling pathways involved in the production of IL-12 in response to soluble toxoplasma antigen (STAg), wild-type and TRAF6−/− mice were inoculated with STAg, and the production of IL-12(p40) was determined. TRAF6−/− mice failed to produce IL-12(p40) in response to STAg, and TRAF6−/− macrophages stimulated with STAg also failed to produce IL-12(p40). Studies using Western blot analysis of wild-type and TRAF6−/− macrophages revealed that stimulation with STAg resulted in the rapid TRAF6-dependent phosphorylation of p38 and extracellular signal-related kinase, which differentially regulated the production of IL-12(p40). The studies presented here demonstrate for the first time that the production of IL-12(p40) in response to toxoplasma is dependent upon TRAF6 and p38 MAPK.

Toxoplasma gondii is an obligate intracellular parasite. The principal pathogenic form of the parasite is in the tachyzoite stage of the life cycle (10). Tachyzoites replicate rapidly in all nucleated cells of the intermediate host (14), and the ability to mount a rapid protective immune response is essential to inhibiting tachyzoite proliferation. The development of both innate and adaptive resistance to this parasite is dependent upon the ability of macrophages and dendritic cells to produce interleukin-12 (IL-12) (40). IL-12 is critical to the activation of NK cells and the development of Th1 effector cells and stimulates the production of gamma interferon (IFN-γ), which is essential for resistance to this parasite and many other intracellular pathogens (12, 13, 39).

Biologically active IL-12(p70) is an inducible, heterodimeric cytokine composed of two subunits, IL-12(p40) and IL-12(p35), linked by a disulfide bond (21). The two subunits are under the control of two separate genes (43). Regulation of biologically active IL-12(p70) depends upon transcriptional regulation of the gene encoding the IL-12(p40) subunit (23). Many microbial products that stimulate the production of IL-12(p40) signal through the highly evolutionarily conserved group of Toll-like receptors (TLR) expressed on the surfaces of antigen-presenting cells (6, 26, 38, 47, 49). Engagement of TLR results in recruitment of the adaptor molecule MyD88 and two serine/threonine kinases, IL-1 receptor-associated kinase (IRAK) and IRAK2, to the receptor complex. These kinases interact with the adaptor molecule TRAF6, which links them to TAK-1 and NF-κB-inducing kinase (4). Phosphorylation of the inhibitory IκB proteins by the IκB kinase complex results in the activation and nuclear translocation of the NF-κB family of transcription factors, which regulate the production of IL-12(p40) (18, 28, 30). The proximal signaling events in TLR-associated mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) activation are similar to those in TLR-associated NF-κB activation and involve MyD88, IRAK, TRAF6, and TAK-1 (5). The MAPKs p38, extracellular signal-related kinase (ERK), and Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) are serine/threonine kinases that influence the phosphorylation and activation status of multiple transcription factors that regulate key components of the immune response (29, 37). Furthermore, p38 and ERK have recently been shown to differentially regulate the production of IL-12 and have been implicated in host-mediated resistance to various pathogens. In those studies, bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS), lipophosphoglycans from Leishmania, or glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchors from Trypanosoma cruzi induced the phosphorylation of p38 and ERK in macrophages (16, 32, 46). Using specific inhibitors of MAPK phosphorylation, these studies further showed that pathogen-induced phosphorylation of p38 promoted the production of IL-12, while phosphorylation of ERK inhibited IL-12 production by IFN-γ-primed macrophages.

Recent studies have indicated that early production of IL-12 during toxoplasma infection is dependent on MyD88 (27, 35). Thus, MyD88−/− mice infected with T. gondii had an 80% reduction in plasma levels of IL-12(p40) during the acute phase of toxoplasma infection, failed to control the parasite burden, and displayed increased susceptibility comparable to that of infected IL-12(p40)−/− mice (35). Furthermore, TLR-2−/− mice infected with a high dose of toxoplasma cysts (300 cysts) produced reduced amounts of IL-12 and IFN-γ compared to wild-type (WT) controls and died within 8 days of infection (27). Taken together, these data suggest that T. gondii is likely to signal through TLR and initiate the same proximal signaling events leading to the production of IL-12 as other microbial stimuli.

Although many studies have demonstrated the importance of the NF-κB family of transcription factors, in particular c-Rel, in the regulation of IL-12(p40) production in response to many microbial products which signal through TLR (24, 34), in vitro and in vivo studies have revealed NF-κB-independent pathways for the production of IL-12(p40) in response to T. gondii (8, 24). Studies from our laboratory have shown that macrophages from NF-κB1−/−(unpublished data), NF-κB2−/−, c-Rel−/−, and RelB−/− mice produce normal levels of IL-12(p40) following infection with T. gondii or stimulation with soluble toxoplasma antigen (STAg) (8, 9, 24). Furthermore, studies have demonstrated that T. gondii infection actively inhibits NF-κB activation (7, 41), suggesting that NF-κB-independent pathways of IL-12 production are essential for host resistance to this pathogen.

The studies presented here were aimed at elucidating the intracellular signaling pathways involved in the production of IL-12(p40) in response to T. gondii. The data demonstrate that TRAF6-dependent activation of p38 MAPK is required for the production of IL-12(p40) in macrophages in response to toxoplasma antigen. Furthermore, these studies indicate that toxoplasma antigen also activates ERK, which leads to the inhibition of IL-12(p40) production, and this may represent a strategy of the parasite to evade early host immune responses.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice and inoculations.

WT C57BL/6 mice (age, 4 to 6 weeks) were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, Maine). TRAF6-deficient (TRAF6−/−)mice have been previously described (22). Age- and sex-matched mice were inoculated intraperitoneally (i.p.) with 25 μg of STAg. STAg was prepared from in vitro-cultured tachyzoites of T. gondii strain RH as previously described (42).

Antibodies and reagents.

Anti-phospho-ERK1/2, anti-ERK, anti-phospho-p38, anti-JNK, and anti-phospho-JNK were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, Mass.), and anti-p38 MAPK was obtained from Santa Cruz (Santa Cruz, Calif.). Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G was obtained from Pierce (Rockford, Ill.). MAPK inhibitors specific to the serine/threonine phosphorylation sites of MEK1 (PD98059), p38 (SB203580), p38β (SB202190), and a negative control reagent for the MAPK inhibitors (SB202474) were purchased from Calbiochem (San Diego, Calif.).

Macrophage cultures.

Bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMMφ) were prepared as previously described (8). Briefly, bone marrow cells obtained from C57Bl/6 mice were cultured in complete Dulbecco's minimal essential medium (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Carlsbad, Calif.) containing 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (U.S. Bio-Technologies Inc., Parkerford, Penn.), 100 U of penicillin/ml (Invitrogen Life Technologies), 10 μg of streptomycin/ml (Invitrogen Life Technologies), and 30% L-cell conditioned medium (from L929 cells) at 37°C for 7 days. Splenic macrophages were prepared from the spleens of 2-week-old TRAF6−/− and WT mice. Briefly, the spleens were dissociated in RPMI medium containing 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, 100 U of penicillin/ml, 10 μg of streptomycin/ml, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 1% nonessential amino acids, and 0.05 mM 2-mercaptoethanol. Erythrocytes were removed by lysis in 0.86% NH4Cl. Cells were washed twice and resuspended in complete Dulbecco's minimal essential medium supplemented with 30% L-cell conditioned medium. Cells were cultured at 37°C for 7 days.

Macrophage activation and measurement of IL-12.

BMMφ or splenic macrophages were plated at 4 × 105 cells/well in 96-well plates (BD Labware, Franklin Lakes, N.J.) and primed with IFN-γ (100 U/ml) for 24 h. Cells were then pretreated with PD98059 (10 μM), SB203580 (10 μM), SB202190 (10 μM), or SB202474 (10 μM) for 1 h followed by stimulation with purified LPS (Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium; Sigma) (100 ng/ml) or STAg (50 μg/ml) for 20 h at 37°C under 5% CO2. IL-12(p40) levels in culture supernatants and serum were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) using monoclonal antibody C17.8 and biotinylated C15.6 (grown from hybridomas provided by Giorgio Trinchieri, Wistar Institute, Philadelphia, Penn.) as previously described (8).

Preparation of cell lysates and Western blot analysis.

Cells were plated at 1.2 × 106 cells/well in 24-well plates (BD Labware) and activated as described above. Cells were then harvested, washed with Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline (Cellgro; Mediatech Inc.), and lysed in HNTG lysis buffer (0.1% Triton X-100, 20 mM HEPES [pH 7.5], 10% glycerol, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM dithiothreitol) by incubation on ice for 30 min. Lysates were then centrifuged at 13,000 × g at 4°C for 10 min. The protein concentrations of the lysates were determined using the MicroBCA protein assay reagent (Pierce). Cell lysates were resolved on a sodium dodecyl sulfate-10% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis gel and then transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.) using a Trans-Blot Semi-Dry cell (Bio-Rad) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Nitrocellulose filters were then incubated with wash buffer (25 mM Tris [pH 7.5], 500 mM NaCl, 0.1% [vol/vol] Tween 20) containing 5% milk protein for 1 h to block nonspecific protein binding. Primary antibodies were diluted 1:1,000 in wash buffer containing 0.5% milk protein and applied to the filter overnight at 4°C. Following washing, the blots were incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (diluted 1:5,000 in wash buffer containing 0.5% milk protein) for 45 min at room temperature. Immunoreactive bands were visualized by the enhanced chemiluminescence system (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, N.J.). In some experiments, blots were stripped and reprobed. Briefly, nitrocellulose membranes were washed several times in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% (vol/vol) Tween. Membranes were incubated at 65°C in enhanced chemiluminescence stripping buffer (2 M Tris, 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 14.4 M 2-mercaptoethanol) for 30 min, washed several times in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% (vol/vol) Tween, and then reprobed.

Statistics.

INSTAT software (GraphPad, San Diego, Calif.) was used for unpaired two-tailed Student's t tests. A P value of <0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

TRAF6 is essential for the production of IL-12 in response to toxoplasma antigen.

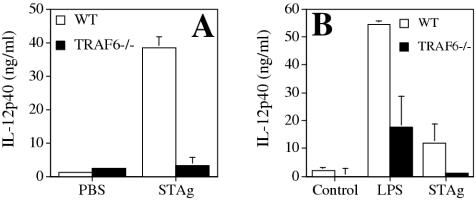

TRAF6 is an adaptor protein that is rapidly recruited in response to TLR engagement and is involved in the activation of NF-κB and MAPK. To determine whether TRAF6 is required for the production of IL-12 in response to STAg, WT and TRAF6−/− mice were injected i.p. with STAg, and serum levels of IL-12(p40) were measured 6 h later. Whereas WT mice showed a significant increase in serum levels of IL-12(p40) in response to STAg injection, TRAF6−/− mice showed no increase in production of IL-12 when compared to controls injected with phosphate-buffered saline (Fig. 1A). Recent studies have shown that CD8α+ dendritic cells are the principal source of IL-12(p40) following injection of naïve mice with STAg (31). Since TRAF6−/− mice have a reduced number of dendritic cells in the spleen (22), this may contribute to the reduction in the amount of IL-12(p40) produced in response to STAg. Therefore, in order to determine whether there is a general intrinsic requirement for TRAF6 in the production of IL-12(p40) in response to STAg, WT or TRAF6−/− macrophages derived from splenic precursors were primed with IFN-γ for 24 h and then stimulated with either purified LPS or STAg, and then IL-12(p40) production in the culture supernatants was measured (Fig. 1B). Splenic macrophages were used because of the difficulty in getting bone marrow precursors from TRAF6−/− mice (unpublished observations). In response to LPS, TRAF6−/− macrophages showed a 50% reduction in IL-12(p40) production compared to that of WT controls. In contrast to WT controls, TRAF6−/− macrophages failed to produce IL-12(p40) in response to STAg (P < 0.005). In these experiments, the priming of macrophages with IFN-γ was necessary to detect production of IL-12(p40) in response to STAg (data not shown). Taken together, these data indicate that TRAF6 is essential for the production of IL-12(p40) in response to STAg.

FIG. 1.

TRAF6 is essential for the production of IL-12 in response to toxoplasma antigen. (A) WT and TRAF6−/− mice were injected i.p. with 25 μg of STAg, and serum IL-12(p40) levels were measured by ELISA 6 h later. PBS, phosphate-buffered saline. (B) Macrophages derived from splenic precursors were primed with IFN-γ for 24 h and then treated with LPS (100 ng/ml) or STAg (50 μg/ml) for 20 h. Culture supernatants were analyzed for IL-12(p40) by ELISA. The data indicate mean values ± standard deviations (SD) of results from triplicate wells.

Activation of p38 MAPK is required for the production of IL-12 in response to T. gondii.

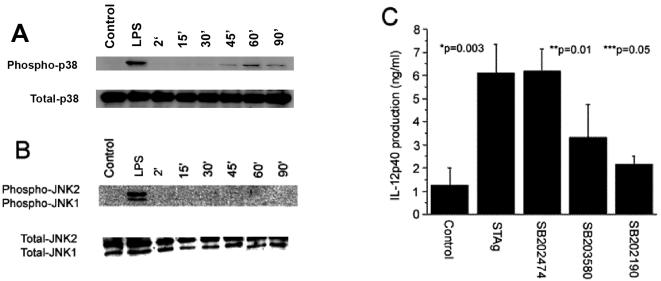

Signaling downstream of TRAF6 diverges into NF-κB and MAPK activation pathways. Since studies have demonstrated that individual NF-κB family members are not required for the production of IL-12 (8, 9, 24) and STAg failed to activate NF-κB in IFN-γ primed macrophages (data not shown), experiments were performed to assess the role of MAPKs in response to STAg. Therefore, to determine whether p38 and JNK are activated in response to stimulation with STAg, WT BMMφ were primed with IFN-γ and stimulated with STAg. Cell lysates were analyzed for phosphorylated p38 and phosphorylated JNK1/2 at varying time points after stimulation (Fig. 2A and B). Phosphorylation of p38 occurred within 15 min of stimulation and peaked at 60 min. In contrast, STAg did not induce phosphorylation of JNK1/2. To determine whether p38 phosphorylation was required for the production of IL-12 in response to toxoplasma antigen, BMMφ were treated with the p38 MAPK inhibitors SB203580 and SB202190 and then stimulated with STAg and IL-12(p40) levels were measured in the culture supernatants (Fig. 2C). Treatment with the p38 inhibitor SB203580, but not the negative control reagent, SB202474, resulted in a significant reduction of IL-12(p40) production in response to STAg. Furthermore, the specific p38β inhibitor SB202190 resulted in a similar reduction of IL-12(p40) production, suggesting that p38β MAPK is the principal p38 MAPK required for the production of IL-12(p40) in response to STAg. Similar results were observed with splenic macrophages (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Activation of p38 MAPK is required for the production of IL-12 in response to toxoplasma antigen. (A and B) BMMφ were primed with IFN-γ for 24 h and then treated with STAg (50 μg/ml). Cell lysates were analyzed for phosphorylated and total levels of p38 MAPK (A) and phosphorylated and total levels of JNK1 and JNK2 (B) by Western blot analysis at the times indicated. (C) BMMφ were primed with IFN-γ for 24 h and then treated with SB202474 (10 μM), SB203580 (10 μM), or SB202190 (10 μM) for 1 h followed by stimulation with STAg (50 μg/ml) for 20 h. Culture supernatants were then analyzed by ELISA for IL-12(p40) production. The data indicate mean values ± SD of results from triplicate wells. Each experiment was performed three times.

Activation of ERK inhibits IL-12 production in response to toxoplasma antigen.

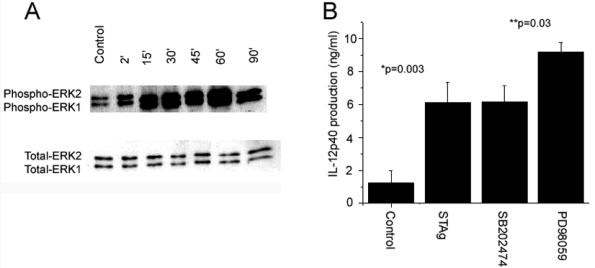

Previous studies have shown that microbial stimuli can activate ERK and that this MAPK can inhibit the production of IL-12 (16, 32, 46). To determine whether toxoplasma antigen also activates ERK, IFN-γ-primed BMMφ were stimulated with STAg, and cell lysates were analyzed for the presence of phosphorylated ERK1/2. STAg rapidly induced phosphorylation of ERK within 2 min with maximum levels of phospho-ERK occurring at 60 min (Fig. 3A). Furthermore, to determine whether STAg-induced ERK activation inhibited IL-12 production in these cultures, cells were preincubated with the MEK1 inhibitor PD98059, which specifically inhibits ERK phosphorylation, and levels of IL-12 in the culture supernatants were measured by ELISA (Fig. 3B). The production of IL-12 was significantly increased in the presence of PD98059 (P = 0.03), indicating that toxoplasma-induced activation of ERK inhibits production of IL-12(p40).

FIG. 3.

Activation of ERK inhibits IL-12 production in response to toxoplasma antigen. (A) BMMφ were primed with IFN-γ for 24 h and then treated with STAg (50 μg/ml). Cell lysates were analyzed for phosphorylated and total levels of ERK1 and ERK2 at the times indicated. (B) BMMφ were primed with IFN-γ for 24 h and then treated with SB202474 (10 μM) (negative control) or PD98059 (10 μM) for 1 h before being stimulated with STAg (50 μg/ml) for 20 h. Culture supernatants were then analyzed by ELISA for IL-12(p40) production. The data indicate mean values ± SD of results from triplicate wells. Each experiment was performed three times.

TRAF6 is essential for p38 and ERK phosphorylation in response to toxoplasma antigen.

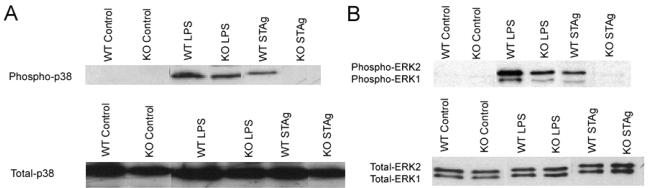

To determine whether TRAF6 is required for STAg-induced phosphorylation of p38 and ERK, WT and TRAF6−/− macrophages derived from splenic precursors were primed with IFN-γ and stimulated with either LPS or STAg, and cell lysates were analyzed for the presence of phosphorylated forms of p38 and ERK1/2. WT and TRAF6−/− macrophages stimulated with LPS showed comparable increases in levels of phospho-p38 (Fig. 4A). In the absence of TRAF6, LPS-induced phosphorylation of ERK1/2 was reduced, although a TRAF6-independent mechanism of ERK phosphorylation was evident (Fig. 4B). In contrast, whereas WT macrophages stimulated with STAg showed an increase in levels of phosphorylated p38 and ERK1/2, TRAF6−/− macrophages showed no increase in phospho-p38 and phospho-ERK1/2 levels following stimulation with STAg (Fig. 4). Total levels of p38 and ERK1/2 were comparable in WT and TRAF6−/− splenic macrophages (Fig. 4). Together, these data demonstrate that p38 and ERK differentially regulate the production of IL-12 in response to STAg and that TRAF6 is essential for the activation of both pathways.

FIG. 4.

TRAF6 is essential for p38 and ERK phosphorylation in response to toxoplasma antigen. WT and TRAF6−/− macrophages derived from splenic precursors were primed with IFN-γ for 24 h and stimulated with either LPS or STAg for 45 min. Cell lysates were analyzed by Western blotting for the presence of total and phosphorylated forms of p38 (A) or total and phosphorylated forms of ERK1 and ERK2 (B). KO, knockout mutant.

DISCUSSION

The data presented here reveal that TRAF6 is essential for the production of IL-12(p40) by macrophages in response to STAg. Furthermore, as CD8α+ dendritic cells are the primary source of IL-12 production following inoculation with STAg (31), our in vivo results suggest that there is an intrinsic requirement for TRAF6 in IL-12 production by CD8α+ dendritic cells in response to STAg, although the reduced number of splenic dendritic cells in TRAF6−/− mice may also contribute to the observed decrease in production of IL-12(p40) in vivo. These studies help to define the signaling pathway initiated by STAg and, based on the present understanding, place TRAF6 downstream of MyD88. However, other pathways are also involved, and MyD88-independent production of IL-12 during toxoplasma infection is thought to occur via G-protein-coupled signaling downstream of the chemokine receptor CCR5 (1, 2, 35). CCR5−/− mice infected with an avirulent strain of T. gondii produced 50% less IL-12(p40) than WT controls and failed to control the parasite burden (1). Dendritic cells from these mice also produced 60 to 75% less IL-12(p40) than WT dendritic cells following stimulation with STAg. Furthermore, defects in STAg-induced IL-12(p40) production were even more profound in dendritic cells from Giα2 −/− mice, indicating the importance of small-G-protein signaling in the production of IL-12(p40) in response to toxoplasma antigen (2). Thus, the data presented here showing the complete absence of STAg-induced IL-12(p40) production by TRAF6−/− mice suggest that both MyD88 and G-protein-coupled signaling pathways, required for the production of IL-12 by T. gondii (35), are dependent on TRAF6. Indeed, recent studies have revealed that the small G protein Ras lies downstream of TRAF6 and participates in IL-1-induced p38 MAPK activation (25). Presently, it is unknown which components of STAg induce IL-12 production by macrophages. Recent studies indicate that different components of STAg induce the production of IL-12 in different cell types; toxoplasma cyclophilin (C-18) induces IL-12 production by dendritic cells (3), while an unidentified toxoplasma component distinct from C-18 is responsible for inducing IL-12 production by neutrophils (11). Although the parasite molecule responsible for the TRAF6-dependent production of IL-12 by macrophages is unknown, recent studies have demonstrated that it is likely to signal via TLR2 (11).

TRAF6 is an important adaptor molecule involved in TLR signaling pathways leading to MAPK activation (25). The data presented here show that stimulation of macrophages with LPS results in TRAF6-dependent and -independent phosphorylation of p38 and ERK. In contrast, STAg-induced activation of p38 and ERK in macrophages is entirely dependent on TRAF6. Furthermore, studies presented here using specific inhibitors of p38β reveal that TRAF6-dependent phosphorylation of p38β is essential for the production of IL-12(p40) by macrophages in response to STAg. In addition, the finding that toxoplasma-induced IL-12 production by WT macrophages is almost completely abolished by p38 inhibitors further supports studies which indicate that toxoplasma-induced production of IL-12 is independent of NF-κB.

Although the exact mechanism by which p38 MAPK promotes the production of IL-12(p40) is undetermined, it is known to phosphorylate transcription factors, such as IRFs, C/EBP, ETS, and NF-κB that bind to the IL-12(p40) promoter and influence its activity (15, 45, 48). However, recent studies in LPS-stimulated macrophages have shown that neither p38 nor ERK influences the binding of NF-κB complexes (p50/p50, p50/c-Rel, and p50/p65) or the F1 complex (containing the transcription factors c-Rel, IRF-1, and GLP109) to the IL-12(p40) promoter (16). Given that the transcription factors ICSBP and IRF-1 are required for the production of IL-12 in response to T. gondii infection (33, 36), it is tempting to speculate that p38 MAPK may promote IL-12(p40) production indirectly, via its effects on these transcription factors and their binding to the IL-12(p40) promoter.

The MAPK subfamilies are known to differentially regulate the production of IL-12 in response to LPS (16, 17). Stimulation of macrophages with LPS results in phosphorylation of p38, ERK, and JNK, and complex cross talk between the p38 and ERK pathways regulates the production of IL-12. For example, ERK acts to down-regulate p38 activation by inducing MKP-1, which binds to the carboxyl terminal of p38, decreasing its effect on IL-12 transcription (19). Furthermore, phospho-ERK also induces the production of IL-10, which suppresses IL-12 production (46). The studies presented here reveal similarity in the differential regulation of IL-12(p40) production in macrophages by p38 and ERK in response to STAg. Interestingly, other parasitic stimuli, such as Leishmania lipophosphoglycan and T. cruzi glycosylphosphatidylinositol, also inhibit the production of IL-12 by macrophages by activating ERK and down-regulating p38 activation (16). Furthermore, recent studies have shown that invasion of human and mouse monocytes with T. gondii tachyzoites triggers the phosphorylation of p38, JNK, and ERK (20, 44). Thus, activation of ERK and inhibition of IL-12 production, like inhibition of NF-κB activation, may represent parasite strategies to avoid or delay activation of the immune response, providing a window of opportunity for the parasite to establish infection. These findings suggest that therapeutic inhibition of ERK activation during T. gondii infection may promote IL-12 responses and inhibit parasite replication.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants KO8 AI50827-01, AI055400, AI46288, and AI42334.

Editor: W. A. Petri, Jr.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aliberti, J., C. Reis e Sousa, M. Schito, S. Hieny, T. Wells, G. B. Huffnagle, and A. Sher. 2000. CCR5 provides a signal for microbial induced production of IL-12 by CD8α+ dendritic cells. Nat. Immunol. 1:83-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aliberti, J., and A. Sher. 2002. Role of G-protein-coupled signaling in the induction and regulation of dendritic cell function by Toxoplasma gondii. Microbes Infect. 4:991-997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aliberti, J., J. G. Valenzuela, V. B. Carruthers, S. Hieny, J. Andersen, H. Charest, C. Reis e Sousa, A. Fairlamb, J. M. Ribeiro, and A. Sher. 2003. Molecular mimicry of a CCR5 binding-domain in the microbial activation of dendritic cells. Nat. Immunol. 4:485-490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barton, G. M., and R. Medzhitov. 2003. Toll-like receptor signaling pathways. Science 300:1524-1525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baud, V., Z. G. Liu, B. Bennett, N. Suzuki, Y. Xia, and M. Karin. 1999. Signaling by proinflammatory cytokines: oligomerization of TRAF2 and TRAF6 is sufficient for JNK and IKK activation and target gene induction via an amino-terminal effector domain. Genes Dev. 13:1297-1308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brightbill, H. D., D. H. Libraty, S. R. Krutzik, R. B. Yang, J. T. Belisle, J. R. Bleharski, M. Maitland, M. V. Norgard, S. E. Plevy, S. T. Smale, P. J. Brennan, B. R. Bloom, P. J. Godowski, and R. L. Modlin. 1999. Host defense mechanisms triggered by microbial lipoproteins through toll-like receptors. Science 285:732-736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Butcher, B. A., L. Kim, P. F. Johnson, and E. Y. Denkers. 2001. Toxoplasma gondii tachyzoites inhibit proinflammatory cytokine induction in infected macrophages by preventing nuclear translocation of the transcription factor NF-κB. J. Immunol. 167:2193-2201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Caamano, J., J. Alexander, L. Craig, R. Bravo, and C. A. Hunter. 1999. The NF-κB family member RelB is required for innate and adaptive immunity to Toxoplasma gondii. J. Immunol. 163:4453-4461. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caamano, J., C. Tato, G. Cai, E. N. Villegas, K. Speirs, L. Craig, J. Alexander, and C. A. Hunter. 2000. Identification of a role for NF-κB2 in the regulation of apoptosis and in maintenance of T cell-mediated immunity to Toxoplasma gondii. J. Immunol. 165:5720-5728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carruthers, V. B. 2002. Host cell invasion by the opportunistic pathogen Toxoplasma gondii. Acta Trop. 81:111-122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Del Rio, L., B. A. Butcher, S. Bennouna, S. Hieny, A. Sher, and E. Y. Denkers. 2004. Toxoplasma gondii triggers myeloid differentiation factor 88-dependent IL-12 and chemokine ligand 2 (monocyte chemoattractant protein 1) responses using distinct parasite molecules and host receptors. J. Immunol. 172:6954-6960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Denkers, E. Y., L. Del Rio, and S. Bennouna. 2003. Neutrophil production of IL-12 and other cytokines during microbial infection. Chem. Immunol. Allergy 83:95-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Denkers, E. Y., and R. T. Gazzinelli. 1998. Regulation and function of T-cell-mediated immunity during Toxoplasma gondii infection. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 11:569-588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dubey, J. P. 1998. Advances in the life cycle of Toxoplasma gondii. Int. J. Parasitol. 28:1019-1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Faure, V., C. Hecquet, Y. Courtois, and O. Goureau. 1999. Role of interferon regulatory factor-1 and mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways in the induction of nitric oxide synthase-2 in retinal pigmented epithelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 274:4794-4800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Feng, G. J., H. S. Goodridge, M. M. Harnett, X. Q. Wei, A. V. Nikolaev, A. P. Higson, and F. Y. Liew. 1999. Extracellular signal-related kinase (ERK) and p38 mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinases differentially regulate the lipopolysaccharide-mediated induction of inducible nitric oxide synthase and IL-12 in macrophages: Leishmania phosphoglycans subvert macrophage IL-12 production by targeting ERK MAP kinase. J. Immunol. 163:6403-6412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feng, W. G., Y. B. Wang, J. S. Zhang, X. Y. Wang, C. L. Li, and Z. L. Chang. 2002. cAMP elevators inhibit LPS-induced IL-12 p40 expression by interfering with phosphorylation of p38 MAPK in murine peritoneal macrophages. Cell Res. 12:331-337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gri, G., D. Savio, G. Trinchieri, and X. Ma. 1998. Synergistic regulation of the human interleukin-12 p40 promoter by NF-κB and Ets transcription factors in Epstein-Barr virus-transformed B cells and macrophages. J. Biol. Chem. 273:6431-6438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hutter, D., P. Chen, J. Barnes, and Y. Liu. 2000. Catalytic activation of mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase phosphatase-1 by binding to p38 MAP kinase: critical role of the p38 C-terminal domain in its negative regulation. Biochem. J. 352:155-163. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim, L., B. A. Butcher, and E. Y. Denkers. 2004. Toxoplasma gondii interferes with lipopolysaccharide-induced mitogen-activated protein kinase activation by mechanisms distinct from endotoxin tolerance. J. Immunol. 172:3003-3010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kobayashi, M., L. Fitz, M. Ryan, R. M. Hewick, S. C. Clark, S. Chan, R. Loudon, F. Sherman, B. Perussia, and G. Trinchieri. 1989. Identification and purification of natural killer cell stimulatory factor (NKSF), a cytokine with multiple biologic effects on human lymphocytes. J. Exp. Med. 170:827-845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kobayashi, T., P. T. Walsh, M. C. Walsh, K. M. Speirs, E. Chiffoleau, C. G. King, W. W. Hancock, J. H. Caamano, C. A. Hunter, P. Scott, L. A. Turka, and Y. Choi. 2003. TRAF6 is a critical factor for dendritic cell maturation and development. Immunity 19:353-363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ma, X., and G. Trinchieri. 2001. Regulation of interleukin-12 production in antigen-presenting cells. Adv. Immunol. 79:55-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mason, N., J. Aliberti, J. C. Caamano, H. C. Liou, and C. A. Hunter. 2002. Cutting edge: identification of c-Rel-dependent and -independent pathways of IL-12 production during infectious and inflammatory stimuli. J. Immunol. 168:2590-2594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McDermott, E. P., and L. A. O'Neill. 2002. Ras participates in the activation of p38 MAPK by interleukin-1 by associating with IRAK, IRAK2, TRAF6, and TAK-1. J. Biol. Chem. 277:7808-7815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Medzhitov, R., P. Preston-Hurlburt, and C. A. Janeway, Jr. 1997. A human homologue of the Drosophila Toll protein signals activation of adaptive immunity. Nature 388:394-397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mun, H. S., F. Aosai, K. Norose, M. Chen, L. X. Piao, O. Takeuchi, S. Akira, H. Ishikura, and A. Yano. 2003. TLR2 as an essential molecule for protective immunity against Toxoplasma gondii infection. Int. Immunol. 15:1081-1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Murphy, T. L., M. G. Cleveland, P. Kulesza, J. Magram, and K. M. Murphy. 1995. Regulation of interleukin 12 p40 expression through an NF-κB half-site. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15:5258-5267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.O'Neill, L. A. 2000. The interleukin-1 receptor/Toll-like receptor superfamily: signal transduction during inflammation and host defense. Sci. STKE 2000:RE1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Plevy, S. E., J. H. Gemberling, S. Hsu, A. J. Dorner, and S. T. Smale. 1997. Multiple control elements mediate activation of the murine and human interleukin 12 p40 promoters: evidence of functional synergy between C/EBP and Rel proteins. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17:4572-4588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reis e Sousa, C., S. Hieny, T. Scharton-Kersten, D. Jankovic, H. Charest, R. N. Germain, and A. Sher. 1997. In vivo microbial stimulation induces rapid CD40 ligand-independent production of interleukin 12 by dendritic cells and their redistribution to T cell areas. J. Exp. Med. 186:1819-1829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ropert, C., I. C. Almeida, M. Closel, L. R. Travassos, M. A. Ferguson, P. Cohen, and R. T. Gazzinelli. 2001. Requirement of mitogen-activated protein kinases and IκB phosphorylation for induction of proinflammatory cytokines synthesis by macrophages indicates functional similarity of receptors triggered by glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchors from parasitic protozoa and bacterial lipopolysaccharide. J. Immunol. 166:3423-3431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Salkowski, C. A., K. Kopydlowski, J. Blanco, M. J. Cody, R. McNally, and S. N. Vogel. 1999. IL-12 is dysregulated in macrophages from IRF-1 and IRF-2 knockout mice. J. Immunol. 163:1529-1536. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sanjabi, S., A. Hoffmann, H. C. Liou, D. Baltimore, and S. T. Smale. 2000. Selective requirement for c-Rel during IL-12 p40 gene induction in macrophages. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:12705-12710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Scanga, C. A., J. Aliberti, D. Jankovic, F. Tilloy, S. Bennouna, E. Y. Denkers, R. Medzhitov, and A. Sher. 2002. Cutting edge: MyD88 is required for resistance to Toxoplasma gondii infection and regulates parasite-induced IL-12 production by dendritic cells. J. Immunol. 168:5997-6001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Scharton-Kersten, T., C. Contursi, A. Masumi, A. Sher, and K. Ozato. 1997. Interferon consensus sequence binding protein-deficient mice display impaired resistance to intracellular infection due to a primary defect in interleukin 12 p40 induction. J. Exp. Med. 186:1523-1534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schroder, N. W., D. Pfeil, B. Opitz, K. S. Michelsen, J. Amberger, U. Zahringer, U. B. Gobel, and R. R. Schumann. 2001. Activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases p42/44, p38, and stress-activated protein kinases in myelo-monocytic cells by Treponema lipoteichoic acid. J. Biol. Chem. 276:9713-9719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schwandner, R., R. Dziarski, H. Wesche, M. Rothe, and C. J. Kirschning. 1999. Peptidoglycan- and lipoteichoic acid-induced cell activation is mediated by toll-like receptor 2. J. Biol. Chem. 274:17406-17409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Scott, P., and C. A. Hunter. 2002. Dendritic cells and immunity to leishmaniasis and toxoplasmosis. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 14:466-470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Scott, P., and G. Trinchieri. 1995. The role of natural killer cells in host-parasite interactions. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 7:34-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shapira, S., K. Speirs, A. Gerstein, J. Caamano, and C. A. Hunter. 2002. Suppression of NF-κB activation by infection with Toxoplasma gondii. J. Infect. Dis. 185(Suppl. 1):S66-S72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sharma, S. D., J. Mullenax, F. G. Araujo, H. A. Erlich, and J. S. Remington. 1983. Western blot analysis of the antigens of Toxoplasma gondii recognized by human IgM and IgG antibodies. J. Immunol. 131:977-983. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Trinchieri, G. 1998. Interleukin-12: a cytokine at the interface of inflammation and immunity. Adv. Immunol. 70:83-243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Valere, A., R. Garnotel, I. Villena, M. Guenounou, J. M. Pinon, and D. Aubert. 2003. Activation of the cellular mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways ERK, p38 and JNK during Toxoplasma gondii invasion. Parasite 10:59-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang, X. Z., and D. Ron. 1996. Stress-induced phosphorylation and activation of the transcription factor CHOP (GADD153) by p38 MAP kinase. Science 272:1347-1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xia, C. Q., and K. J. Kao. 2003. Suppression of interleukin-12 production through endogenously secreted interleukin-10 in activated dendritic cells: involvement of activation of extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase. Scand. J. Immunol. 58:23-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yang, R. B., M. R. Mark, A. L. Gurney, and P. J. Godowski. 1999. Signaling events induced by lipopolysaccharide-activated toll-like receptor 2. J. Immunol. 163:639-643. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yordy, J. S., and R. C. Muise-Helmericks. 2000. Signal transduction and the Ets family of transcription factors. Oncogene 19:6503-6513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang, G., and S. Ghosh. 2001. Toll-like receptor-mediated NF-κB activation: a phylogenetically conserved paradigm in innate immunity. J. Clin. Investig. 107:13-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]