Abstract

The proinflammatory effect of Afa/Dr diffusely adhering Escherichia coli (Afa/Dr DAEC) strains have been recently demonstrated in vitro by showing that polymorphonuclear leukocyte (PMN) transepithelial migration is induced after bacterial colonization of apical intestinal monolayers. The effect of Afa/Dr DAEC-PMN interaction on PMN behavior has been not investigated. Because of the putative virulence mechanism of PMN apoptosis during infectious diseases and taking into account the high level of expression of the decay-accelerating factor (DAF, or CD55), the receptor of Afa/Dr DAEC on PMNs, we sought to determine whether infection of PMNs by Afa/Dr DAEC strains could promote cell apoptosis. We looked at the behavior of PMNs incubated with Afa/Dr DAEC strains once they had transmigrated across polarized monolayers of intestinal (T84) cells. Infection of PMNs by Afa/Dr DAEC strains induced PMN apoptosis characterized by morphological nuclear changes, DNA fragmentation, caspase activation, and a high level of annexin V expression. However, transmigrated and nontransmigrated PMNs incubated with Afa/Dr DAEC strains showed similar elevated global caspase activities. PMN apoptosis depended on their agglutination, induced by Afa/Dr DAEC, and was still observed after preincubation of PMNs with anti-CD55 and/or anti-CD66 antibodies. Low levels of phagocytosis of Afa/Dr DAEC strains were observed both in nontransmigrated and in transmigrated PMNs compared to that observed with the control E. coli DH5α strain. Taken together, these data strongly suggest that interaction of Afa/Dr DAEC with PMNs may increase the bacterial virulence both by inducing PMN apoptosis through an agglutination process and by diminishing their phagocytic capacity.

Diffusely adhering Escherichia coli (DAEC) is one of the six classes of diarrheagenic E. coli (36). Afa/Dr DAEC is responsible for uropathogenic and intestinal infections (48). Epidemiological studies have shown that Afa/Dr DAEC strains are involved in persistent diarrhea in children (22, 33), in 30% of cystitis cases in children, in 30% of pyelonephritis cases in pregnant women, and in recurrent urinary tract infections in young adult women (21, 54). Afa/Dr DAEC strains are defined in vitro by their diffuse adherence pattern on erythrocytes (47) and cultured epithelial HeLa or HEp-2 cells (16, 57). These strains express adhesins of the Afa/Dr family, which include the afimbrial adhesins AfaE-I and AfaE-III, the Dr and Dr-II adhesin, and the fimbrial F1845 adhesin (12, 37, 38, 47). Afa/Dr adhesins mediate bacterial adhesion by binding to a common receptor, the decay-accelerating factor (DAF, or CD55), a complement receptor (41). Moreover, members of the Afa/Dr family of adhesins also recognize another membrane-associated glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored protein on epithelial cells, the carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA, CEACAM5, or CD66e) (26). More recently, it has been demonstrated that a subfamily of Afa/Dr adhesins, including the Dr, AfaE-III, and F1845 adhesins, is involved in adherence to CEA and CEACAM1 (also called biliary glycoprotein [BGP] or CD66a) and CEACAM6 (also called nonspecific cross-reacting antigen [NCA] or CD66c) and the recruitment of CEA, CEACAM1, CEACAM3, and CEACAM6 (8).

Some enteric pathogens are able to induce polymorphonuclear leukocyte (PMN) migration across the intestinal barrier in human diseases (29). It was recently demonstrated that intestinal epithelial cells incubated with different DAEC strains trigger interleukin 8 secretion at the basolateral side of epithelia and then induce PMN transepithelial migration (10, 11). In parallel, it was shown that adherence of Afa/Dr DAEC strains to CD55 expressed on the apical surface of T84 intestinal cells is critical to induce PMN transepithelial migration (10). Moreover, PMN transepithelial migration induced epithelial production of different cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor alpha and interleukin-1β, which in turn promoted the upregulation of CD55 expressed on the apical side of T84 monolayers (11).

Adherence of E. coli to PMNs mediated by type 1 fimbriae and S fimbriae is known to result in a variety of responses from the host cells, including stimulation of the respiratory burst, release of granular contents and other mediators, and increased arachidonate metabolism (34, 60). These effects result in host injury and promote an inflammatory response. Previous studies have shown that adhesins of the Dr family mediate adherence to and agglutination of PMNs (35). This Dr adhesin-mediated adherence to PMNs does not result in significantly increased bacterial killing (35). However, whether adherence to PMNs mediated by Dr family adhesins triggers responses from PMNs has not yet been determined.

Because of the potential pathogenic importance of pathogen-PMN interactions, and because the behavior of PMNs after their interaction with Afa/Dr DAEC is unknown, we undertook the present work to compare the pathogenicities of different Afa/Dr DAEC strains with that of a laboratory strain of E. coli (DH5α) during their interactions with human PMNs. Since induction of apoptosis has been considered to be a virulence mechanism of bacterial pathogens that promotes an inflammatory response, causing tissue damage and facilitating further colonization (65), we sought to determine whether Afa/Dr DAEC strains are able to promote PMN apoptosis and/or phagocytosis. Moreover, as it has been demonstrated that the PMN transepithelial migration process both increases the phagocytic capability (31) and delays the programmed cell death of transmigrated PMNs (40), these effects were compared in transmigrated PMNs incubated with DH5α and Afa/Dr DAEC strains.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

We used the wild-type Afa/Dr DAEC C1845 harboring the fimbrial F1845 adhesin, IH11128 harboring the Dr hemagglutinin, and the E. coli laboratory strain HB101 DH5α transformed with the pSSS1 plasmid producing F1845 adhesin, called pSSS1-DH5α. The E. coli laboratory strain HB101 DH5α served as a negative control. For confocal-microscopy studies, we used green fluorescent protein (GFP)-IH11128 or GFP-DH5α. The strains were grown in colonization factor antigen containing 1% Casamino Acids (BD France, Le Pont de Claix, France), 0.15% yeast extract, 0.005% magnesium sulfate, and 0.0005% manganese chloride in 2% agar for 18 h at 37°C. The E. coli laboratory strain DH5α was grown at 37°C for 18 h in Luria broth base. In some experiments, the IH11128, C1845, and DH5α strains were pretreated with a solution containing inhibitor substances (Sigma-Aldrich, Lyon, France) prepared in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (pH 7.4) and including chloramphenicol (5 mM) and t-butoxycarbonyl-O-benzyl-l-tyrosine (2.5 mM).

PMN preparation and treatment.

Human PMNs were isolated from whole blood using a gelatin sedimentation technique. Briefly, whole blood anticoagulated with citrate-dextrose was centrifuged at 300 × g for 20 min (20°C). The plasma and buffy coat were removed, and the gelatin-cell mixture was incubated at 37°C for 30 min to remove contaminating red blood cells. The residual red blood cells were then lysed with isotonic ammonium chloride. After being washed in Hanks' balanced saline solution (HBSS) without Ca2+ or Mg2+, the cells were counted and resuspended at 5 × 107 PMNs/ml. PMNs (95% pure) with 98% viability by trypan blue exclusion were used within 1 h after isolation.

Cookson and Nataro have reported that DAEC in contact with epithelial cells is gentamicin resistant (15). To study the specific effect occurring during the interaction between the DAEC and PMNs, we performed a gentamicin protection assay (15). Briefly, for phagocytosis and agglutination studies, PMNs were incubated with the different E. coli strains for 1 h in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum using low-attachment Costar plates (VWR International, Fontenay Sous Bois, France). For other experiments, gentamicin (100 μg/ml) was added for 1 h, and the PMNs were washed twice in HBSS and then resuspended in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum in plates supplemented with 50 μg of gentamicin/ml for an additional 1 (caspase 3 activity) or 6 (morphology, DNA fragmentation, and annexin V-propidium iodide [PI] double staining) h.

In experiments using blocking antibody, PMNs were preincubated for 1 h with the specific anti-DAF SCR3 monoclonal antibody (IH4; 20 μg/ml; Abcys, Paris, France) and/or with anti-CD66a (10 μg/ml; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, Calif.) and anti-CD66c (10 μg/ml; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) antibodies before infection with the different bacterial strains. For positive control of apoptosis, PMNs were treated with staurosporine (1 μM).

Morphological study.

The morphological changes of PMNs incubated with bacteria were examined by light microscopy. Briefly, PMNs were fixed with methanol and stained with Wright-Giemsa stain, and the slides were examined by light microscopy. At least 400 cells of each preparation in various fields were counted. Apoptotic cells were easily distinguishable on the bases of chromatin condensation and nuclear fragmentation. To study morphologically the agglutination process induced by bacterial strains, equal numbers of PMNs (e.g., 5 × 103) were seeded on each glass slide. For each condition, cells were counted in 40 random fields at high power (×400), and an average of the total number of PMNs was then determined.

For electron microscopy studies, control PMNs and PMNs infected with different strains of E. coli for 1 h were fixed with 2% freshly prepared formaldehyde in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate (pH 7.4) for 1 h at 4°C. The pellets were rinsed in cacodylate buffer, postfixed in 1% OsO4 for 1 h, dehydrated through graded alcohols, and embedded in epoxy resin. Oriented 1-mm-thick sections were cut with diamond knives, and multiple areas were thinly sectioned, mounted on copper mesh grids, and stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate. Ultrathin sections were examined on a JEOL 1200 XII electron microscope.

For confocal microscopy, we used E. coli (both DH5α and IH11128 strains), expressing GFP. The phagocytosed E. coli in PMNs was observed with a laser scanning fluorescence microscope (Leica, Lyon, France) equipped for epifluorescence.

DNA laddering.

DNA was isolated from 107 PMNs. In brief, the cells were lysed with TES buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, 200 mM EDTA, and 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate) with RNase (20 μg/ml; Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, Ind.) at 37°C for 1 h. Proteins were denatured by incubation with proteinase K (1 mg/ml; Boerhinger Mannheim) at 55°C for 3 h. The denatured proteins were removed by phenol extraction, and the DNA was then precipitated with alcohol overnight at −20°C. The next day, the DNA was rinsed with alcohol, mixed with loading buffer, and then electrophoresed in a 2% agarose gel containing 10 μg of ethidium bromide/ml. The gel was examined and photographed under UV light to detect a regular DNA fragmentation pattern (laddering) characteristic of apoptosis.

Flow cytometry analysis.

PMNs (106) were double stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated annexin V and PI for 15 min at 20°C in a Ca2+-enriched binding buffer (apoptosis detection kit; R&D Systems, Lille, France). They were immediately analyzed on a flow cytometer in the staining solution. Analysis was performed on a FACScan apparatus (Becton Dickinson, Rutherford, N.J.) with the channel number (log scale) representing the mean fluorescence intensity for 10,000 cells.

Ac-DEVD-pNA cleavage assay.

Caspase activity was measured using a previously described colorimetric assay (54). Briefly, control or infected PMNs were sonicated (two pulses of 8 s each) in ice-cold lysis buffer, and then the lysates were centrifuged at 15,000 × g. Cellular extracts (50 μg of protein) were then incubated in a 96-well plate with 0.2 mM acetyl-Asp-Glu-Val-Asp-(p-nitroaniline) (Ac-DEVD-pNA) (caspases 3, 6, and 7; Alexis Corp., San Diego, Calif.) as a substrate for various times at 37°C. Caspase activity was measured at 405 nm in the presence or absence of 1 μM Ac-DEVD-aldehyde (Ac-DEVD-CHO) (blank control; Alexis Corp.). The specific caspase activity was expressed in nanomoles of paranitroaniline released per minute and per milligram of protein.

Immunoblot analysis.

Briefly, PMNs were washed in PBS and resuspended in ice-cold lysis buffer (10 mM HEPES, 3.5 mM MgCl2, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton, 1 mM Na3VO4, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 25 μM leupeptin, 5 mM benzamidine, 1 μM pepstatin, 25 mM aprotinin, 50 mM sodium β-glycerophosphate, 20 mM NaF, 0.5 mM dithiothreitol; all from Sigma-Aldrich). Protein lysates (50 μg) were subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and subsequently electrophoretically transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes. The membranes were incubated in blocking buffer and then probed with anti-caspase-3 antibody (immunoglobulin G2a isotype clone 19; 1 μg/ml; BD Biosciences, San Diego, Calif.) overnight at 4°C. After incubation with peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (rabbit anti-mouse immunoglobulin diluted 1:5,000; Dako, Trappes, France), the antigens were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence detection (ECL kit; Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Orsay, France).

Neutrophil transepithelial migration.

T84 cells (passages 65 to 90), a human colonic carcinoma cell line, were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (clone CCL-248) and grown and maintained as confluent monolayers on collagen-coated permeable supports with detailed modifications (30, 43). For transmigration assays performed in the physiological direction, inverted monolayers were grown on collagen-coated, 0.33-cm2 ring-supported, permeable polycarbonate filters (VWR International). Once isolated, the PMNs were suspended in modified HBSS (without Ca2+ and Mg 2+) with 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.4) (Sigma-Aldrich) at a concentration of 5 × 107/ml before being added to the inverts (106 cells/well). Transmigration of PMNs was initiated by applying 0.1 mM N-formyl-l-methionyl-leucyl-l-phenylalanine (Sigma-Aldrich) to the lower reservoir and incubating it for 15 min to allow a transepithelial chemotactic gradient to form prior to the addition of the PMNs. The physiologically (basolateral-to-apical) directed PMN transepithelial-migration assay was performed for 2 h using low-attachment Costar plates as previously described (30, 43).

Data analysis.

Values are expressed as the mean and standard error of the mean of n experiments. Interreader variability was analyzed by analysis of variance. Means of groups were analyzed by the two-tailed Student t test.

RESULTS

Infection with Afa/Dr DAEC strains accelerates spontaneous human PMN apoptosis.

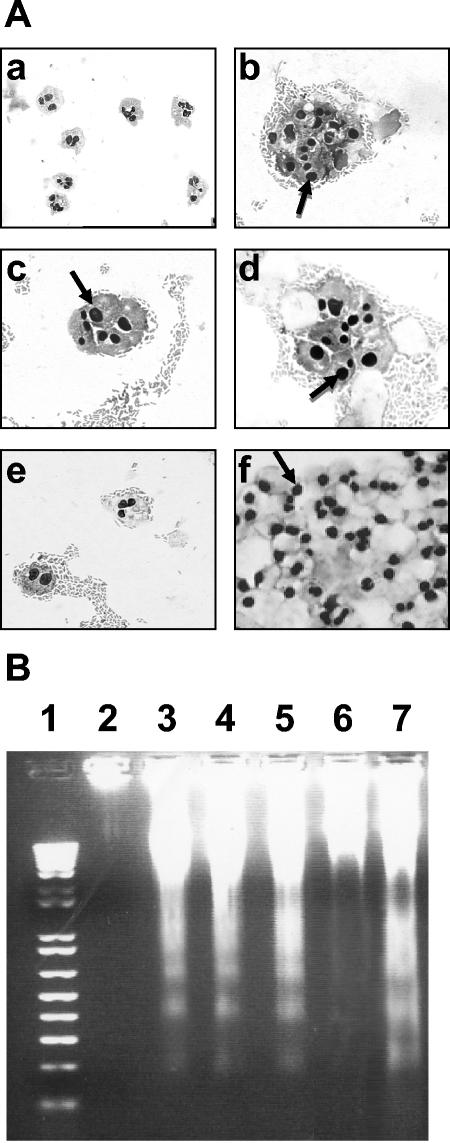

Morphological study of PMNs was performed at 37°C on cells incubated with different strains of Afa/Dr DAEC, followed by a 6-h gentamicin treatment. Morphological analysis revealed an increase in spontaneous PMN apoptosis in comparison to PMNs cultured with the control E. coli DH5α strain. By light microscopy, uninfected PMNs showed a proportion of 5% ± 2% apoptotic cells (Fig. 1A, a). A high percentage of cells with apoptotic features were detected after the addition of wild-type Afa/Dr DAEC IH11128 (Fig. 1A, b) and C1845 (Fig. 1A, d) strains to the cell culture (82% ± 7% and 90% ± 5%, respectively). In order to demonstrate that apoptosis in infected PMNs results from the Afa/Dr adhesins, PMNs were infected with the recombinant E. coli pSSS1-DH5α. As for the wild-type strains, a high rate of apoptosis was noted in pSSS1-DH5α-infected PMNs (85% ± 6%) (Fig. 1A, c). As a negative control, fewer apoptotic bodies and pyknotic nuclei were observed in PMNs incubated with the DH5α strain (25% ± 8%) (Fig. 1A, e). As a positive control, all PMNs were apoptotic after incubation with staurosporine (Fig. 1A, f).

FIG. 1.

(A) Light microscopic analysis of PMNs infected with E. coli strains IH11128, pSSS1-DH5α, C1845, and DH5α. E. coli strains IH11128 (b), pSSS1-DH5α (c), C1845 (d), and DH5α (e) were left in contact with PMNs for 1 h, and the PMNs were stained with Giemsa's stain. Uninfected PMNs at 37°C (a) and staurosporine-treated PMNs (f) were used as negative and positive apoptosis controls, respectively. The arrows indicate apoptotic nuclei. Magnification, ×630 (a) and ×720 (b to f). (B) DNA fragmentation assays on agarose gels. DNA was isolated from PMNs infected with different E. coli strains. The DNA was electrophoresed on 1.2% agarose gels for 1 h at 100 V. DNA was isolated from PMNs infected with IH11128 (lane 3), pSSS1-DH5α(lane 4), C1845 (lane 5), and DH5α (lane 6). Lane 7, 100-bp DNA ladder; lane 1, DNA isolated from uninfected PMNs at 37°C; lane 2, DNA isolated from staurosporine-treated PMNs. These results are representative of three experiments performed on different PMN preparations.

Assessment of PMN apoptosis by DNA gel electrophoresis correlated with the results obtained by light microscopy. Electrophoresis of DNAs isolated from PMNs preincubated with strains IH11128 (Fig. 1B, lane 3), pSSS1-DH5α (Fig. 1B, lane 4), and C1845 (Fig. 1B, lane 5) showed increased internucleosomal DNA fragmentation compared to PMNs incubated with the control E. coli DH5α strain (Fig. 1B, lane 6). No DNA laddering (Fig. 1B, lane 2) was observed in uninfected PMNs, whereas marked DNA fragmentation was observed in PMNs treated with staurosporine (Fig. 1B, lane 7).

PMN apoptosis induced by Afa/Dr DAEC strains is associated with caspase activation and increased expression of annexin V.

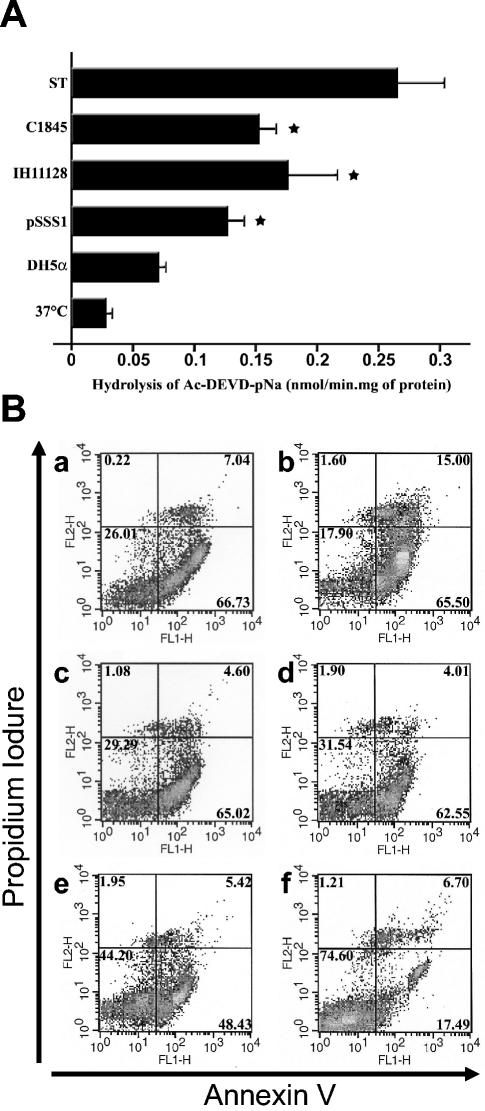

We next analyzed caspase activity in cultured PMNs by using Ac-DEVD-pNA as a substrate. The low basal caspase activity was unaffected by incubation with E. coli DH5α but was strongly increased in PMNs infected with the different Afa/Dr DAEC strains (Fig. 2A). Staurosporine (1 μM) was used as a positive control for caspase activation (0.025 ± 0.006 [37°C] versus 0.08 ± 0.005 [DH5α] versus 0.126 ± 0.012 [pSSS1-DH5α] versus 0.176 ± 0.038 [IH11128] versus 0.153 ± 0.013 [C1845] versus 0.261 ± 0.04 [staurosporine] nmol/min · mg of protein).

FIG. 2.

(A) Caspase-3 activities in PMNs infected with E. coli strains IH11128, pSSS1-DH5α, C1845, and DH5α. The bacteria were left in contact with the PMNs for 1 h and treated with gentamicin as described in Materials and Methods. The values obtained for each condition were compared to those obtained from control PMNs kept in HBSS (−) at 37°C and from staurosporine-treated PMNs (ST) for 3 h. The results represent the average values (± standard deviations) from three independent experiments. *, significant difference from the DH5α strain at P < 0.05. (B) Assessment of apoptosis in PMNs infected with E. coli strains IH11128, pSSS1-DH5α, C1845, and DH5α by annexin V and propidium iodide staining. Shown is annexin V-PI double staining in PMNs infected for 1 h with strains IH11128 (a), pSSS1-DH5α (b), C1845 (c), and DH5α (d) before gentamicintreatment. Uninfected PMNs at 37°C (e) and staurosporine-treated PMNs (f) were used as negative and positive apoptosis controls, respectively. FL1-H, annexin V; FL2-H, PI; upper right windows, necrotic or late apoptotic cells; lower right windows, apoptotic cells; lower left windows, live cells. These results are representative of at least three individual experiments performed on different PMN preparations.

Annexin V-PI double staining of PMNs showed that phosphatidylserine was strongly exposed on the surfaces of PMNs treated with staurosporine (Fig. 2B, a), as well as strains C1845 (Fig. 2B, b), IH11128 (Fig. 2B, c), and pSSS1-DH5α (Fig. 2B, d), in comparison to PMNs treated with strain DH5α (Fig. 2B, e) and untreated PMNs at 37°C (Fig. 2B, f).

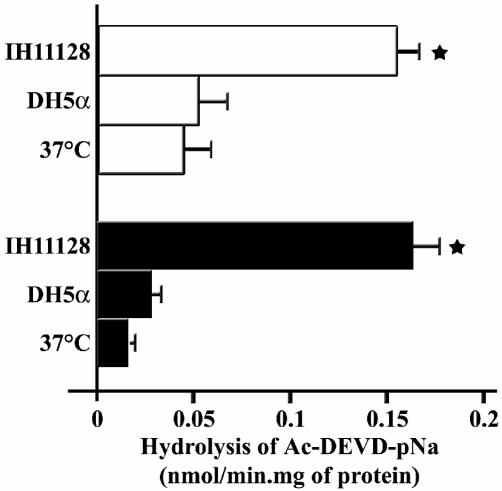

Transepithelial migration of PMNs does not affect caspase activity of PMNs induced by Afa/Dr DAEC strain IH11128.

Caspase activity was used to evaluate the effect of the transmigration process on the kinetics of apoptosis in PMNs infected with the wild-type strain IH11128. As previously demonstrated (40), migration across intestinal T84 monolayers diminished the caspase activity of transmigrated PMNs in comparison to that noted in nontransmigrated PMNs (Fig. 3). However, high caspase activity was still observed in postmigration PMNs infected for 1 h with IH11128 bacteria before gentamicin treatment, whereas this activity was not significantly increased in transmigrated PMNs infected with strain DH5α (0.041 ± 0.005 versus 0.01 ± 0.01 [37°C; nontransmigrated versus transmigrated]; 0.04 ± 0.01 versus 0.026 ± 0.005 [DH5α; nontransmigrated versus transmigrated]; 0.169 ± 0.035 versus 0.186 ± 0.056 [IH11128; nontransmigrated versus transmigrated] nmol/min · mg ofprotein) (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Caspase-3 activity in nontransmigrated PMNs and in transmigrated PMNs infected with E. coli strains IH11128 and DH5α. The bacteria were left in contact with the PMNs for 1 h before gentamicin treatment, as described in Materials and Methods. The values obtained for each condition were compared to those obtained from control PMNs kept in HBSS at 37°C. These results represent the average values (plus standard deviations) from three independent experiments. Open bars, nontransmigrated PMNs; solid bars, transmigrated PMNs; *, significant difference from the transmigrated PMNs at P < 0.05.

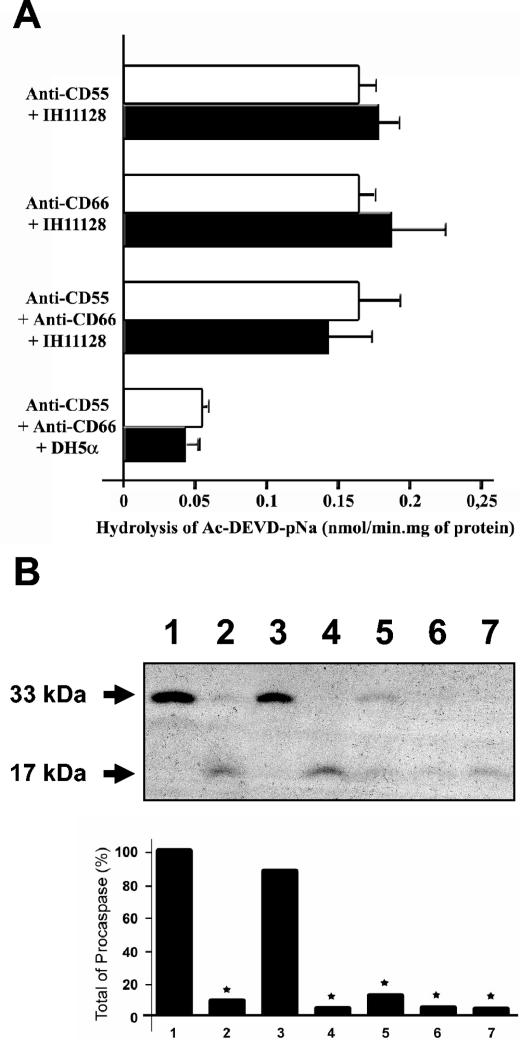

Pretreatment of PMNs with anti-CD55 or anti-CD66 antibody fails to affect caspase 3 activation or global caspase activity in IH11128-infected PMNs.

As shown in Fig. 4A, preincubation of PMNs with anti-CD55, anti-CD66a (CEACAM1), or anti-CD66c (CEACAM6) antibody or the combination of anti-CD55 and anti-CD66 antibodies did not affect the caspase activity observed in PMNs treated with strain IH11128. In the same way, preincubation of PMNs with anti-CD55, anti-CD66a, and anti-CD66c antibodies failed to modulate caspase activity induced by strain DH5α (0.04 ± 0.01 [DH5α] versus 0.05 ± 0.013 [DH5α plus anti-CD55, anti-CD66a, and anti-CD66c antibodies] versus 0.16 ± 0.013 [IH11128] versus 0.17 ± 0.018 [IH11128 plus anti-CD55 antibody] versus 0.18 ± 0.015 [IH11128 plus anti-CD66a and anti-CD66c antibodies] versus 0.145 ± 0.022 [IH11128 plus anti-CD55, anti-CD66a, and anti-CD66c antibodies] nmol/min · mg of protein) (Fig. 4A). Accordingly, IH11128-mediated procaspase 3 activation was not affected by PMN pretreatment with anti-CD55 and/or anti-CD66a and anti-CD66c antibodies (Fig. 4B).

FIG. 4.

(A) Caspase-3 activities of PMNs pretreated with anti-CD55 and/or anti-CD66a and anti-CD66c antibodies and infected with strain IH11128. PMNs pretreated with anti-CD55, anti-CD66a, and anti-CD66c antibodies and infected with E. coli DH5α were used as controls. The results are representative of three experiments performed on different PMN preparations. Open bars, PMNs incubated with anti-CD55 and/or anti-CD66a and anti-CD66c antibodies; solid bars, control PMNs. The error bars indicate standard errors of the mean. (B) (Top) Immunoblot analysis of procaspase 3 activation in PMNs pretreated with anti-CD55 and/or anti-CD66a and anti-CD66c antibodies and untreated PMNs infected with E. coli strain IH11128. Profiles of procaspase 3 expression in PMNs kept at 37°C (lane 1) (to show the endogenous level of caspase), in staurosporine-treated PMNs (lane 2), and in PMNs infected with E. coli strain DH5α (lane 3) were compared to those obtained after PMN infection with E. coli strain IH11128 (lane 4) and with strain IH11128 pretreated with anti-CD55 (lane 5), with both anti-CD66a and anti-CD66c (lane 6), and with anti-CD55, anti-CD66a, and anti-CD66c (lane 7) antibodies. The data are representative of three independent experiments. (Bottom) Densitometric scanning of procaspase 3. The results are expressed as percentages of total procaspase 3 in the negative apoptosis control (37°C).

Caspase activation in PMNs infected with IH11128 bacteria depends on agglutination of PMNs by bacterial strains.

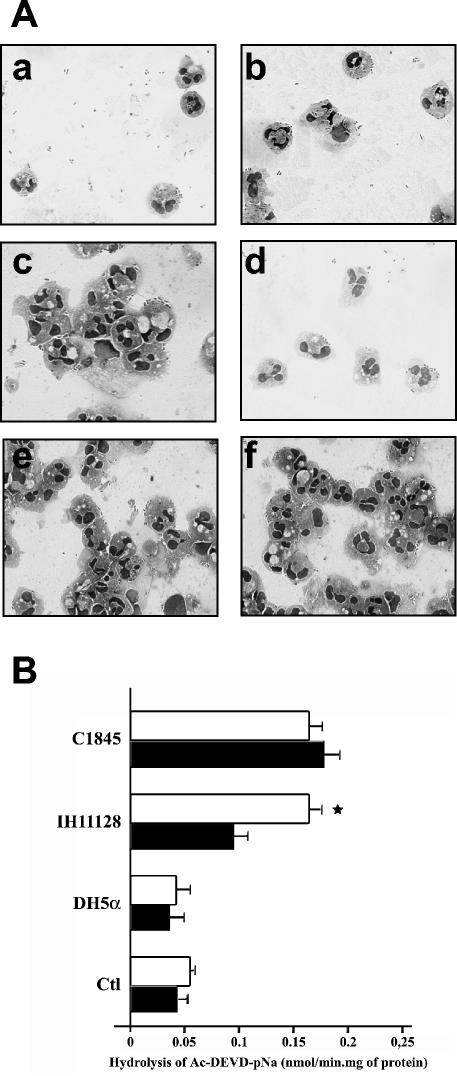

As shown by light microscopic analysis, incubation of PMNs with IH11128 bacteria triggered a strong PMN agglutination that was inhibited by chloramphenicol (Fig. 5A, c and d). In contrast, PMNs infected with C1845 bacteria showed an agglutination process regardless of the presence of chloramphenicol (Fig. 5A, e and f). As a control, DH5α bacteria failed to induce PMN agglutination either in the presence or the absence of chloramphenicol (Fig. 5A, a and b). The total number of cells observed in 40 high-power fields was almost the same under each condition (450 ± 14). As shown in Fig. 5B, increased caspase activity induced by IH11128 bacteria was also significantly reduced by pretreatment of the bacteria with chloramphenicol (0.09 ± 0.01 versus 0.16 ± 0.03 nmol/min · mg of protein [for pretreated versus untreated IH11128]), whereas caspase activity was unchanged in PMNs infected with strain C1845 regardless of the presence of chloramphenicol (0.16 ± 0.04 versus 0.17 ± 0.03 nmol/min · mg of protein [for pretreated versus untreated C1845]). No difference was noted in the caspase activity levels in PMNs infected with strain DH5α in the presence or absence of chloramphenicol or in control PMNs (0.04 ± 0.01 versus 0.06 ± 0.03 and 0.05 ± 0.02 versus 0.03 ± 0.01 nmol/min · mg of protein [for pretreated versus untreated DH5α and treated versus untreated control PMNs, respectively]) (Fig. 5B).

FIG. 5.

(A) Light microscopic analysis of PMN agglutination and inhibition of PMN agglutination. (a) PMNs plus strain DH5α in PBS for 1 h, unagglutinated; (b) PMNs plus strain DH5α in PBS plus choramphenicol for 1 h, unagglutinated; (c) PMNs plus strain IH11128 in PBS for 1 h, agglutinated; (d) PMNs plus strain IH11128 in PBS plus choramphenicol for 1 h, unagglutinated; (e and f) PMNs plus strain C1845 in PBS with (e) and without (f) chloramphenicol for 1 h, agglutinated. Magnification, ×200. (B) Caspase-3 activities in PMNs infected with E. coli strains IH11128, C1845, and DH5α pretreated (solid bars) or not (open bars) with chloramphenicol. The bacteria were left in contact with the PMNs for 1 h before gentamicin treatment. The values obtained for each condition were compared to those obtained from control PMNs (Ctl) kept in HBSS at 37°C. The results represent the average values (plus standard deviations) from three independent experiments. *, significant difference from the treated IH11128 strain at P < 0.01.

Afa/Dr DAEC strains are poorly engulfed both in nontransmigrated and in transmigrated PMNs.

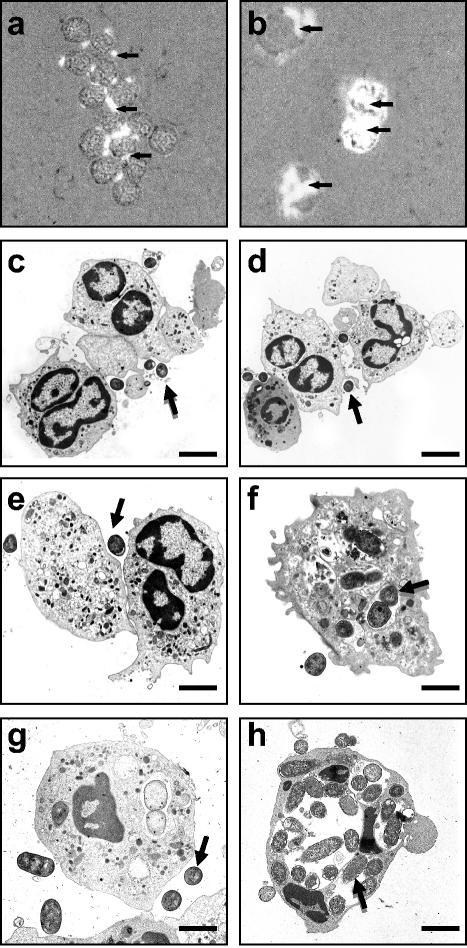

Light microscopy analysis showed significant inhibition of phagocytosis in PMNs infected for 1 h with IH11128-GFP bacteria (Fig. 6a) compared to PMNs infected with DH5α-GFP bacteria (Fig. 6b). Electron microscopy was next used to quantify the bacteria engulfed by nontransmigrated or transmigrated PMNs. As previously described (31), PMNs that had transmigrated across a monolayer of T84 cells exhibited an increased number of phagocytosed bacteria when challenged with control E. coli DH5α for 1 h in comparison with nontransmigrated infected PMNs (11 ± 2 versus 4 ± 2 control E. coli organisms per cell observed in a thin section for transmigrated versus nontransmigrated PMNs; P < 0.01). A significant decrease in the number of engulfed wild-type IH11128 and C1845 bacteria, and of recombinant pSSS1-DH5α bacteria, was observed in nontransmigrated PMNs in comparison with control E. coli (1 ± 1 versus 2 ± 1 versus 1 ± 1 versus 4 ± 1 control E. coli organisms per cell; P < 0.05) (Fig. 6c to f). Moreover, in transmigrated PMNs, the rate of phagocytosis of IH11128 bacteria was identical to that observed in nontransmigrated PMNs (1 ± 1 versus 1 ± 2 bacteria per cell, respectively) (Fig. 6h).

FIG. 6.

(a and b) Light microscopic analysis of PMNs infected with GFP-IH11128 (a) and GFP-DH5α (b) E. coli strains. The bacteria were left in contact with the PMNs for 1 h. Magnification, ×400. The arrows indicate GFP bacteria. (c to h) Transmission electron micrographs of nontransmigrated (c to f) and transmigrated (g and h) PMNs infected for 1 h with E. coli strains IH11128 (c and g), pSSS1-DH5α (d), C1845 (e), and DH5α (f and h). The arrows indicate bacteria. Bars: 10 μm (c and d) and 2 μm (e to h). The results are representative of three experiments performed on different PMN preparations.

DISCUSSION

Upon infection with a pathogen, eukaryotic cells can undergo programmed cell death as an ultimate response (65). Therefore, modulation of apoptosis is often a prerequisite to establish a host-pathogen relationship (65). The balance between PMN apoptosis and necrosis in inflamed tissues is an important determinant of the degree of tissue injury, and dysregulation of PMN apoptosis may lead to the development of chronic inflammatory disease. The behavior of human PMNs in the presence of pathogens and/or their products is variable. Some pathogens delay PMN apoptosis (2, 14, 32, 39, 44, 45). Conversely, other pathogens kill PMNs by inducing or accelerating apoptosis and thus overcome the microbicidal arsenal of the phagocyte (3, 42, 53, 56, 61, 64).

Several studies have demonstrated that the behavior of professional phagocytes during their interaction with E. coli is strongly correlated with the potential virulence of the different strains. Thus, adherent invasive E. coli strains isolated from patients with Crohn's disease survive and replicate within macrophages but do not induce host cell death (23). Conversely, enteroaggregative and cytodetaching E. coli strains induce macrophage cell death (19). Our data showed that Afa/Dr DAEC strains are able to dramatically accelerate PMN apoptosis, indicating that, in addition to epithelial alteration induced by these bacteria (9, 26, 50-52), bacterium-PMN interaction could increase the virulence of Afa/Dr DAEC. The mechanisms underlying PMN apoptosis triggered by E. coli strains have been poorly investigated. Since molecular regulation of PMN apoptosis involves caspase activation (28), we looked for global caspase activity and procaspase 3 expression in PMNs incubated with different Afa/Dr DAEC strains. Our data showed that caspase activity was significantly induced in PMNs pretreated with Afa/Dr strains. In parallel, procaspase 3 was cleaved in PMNs incubated with Afa/Dr strains, whereas cleavage was not observed in PMNs incubated with strain DH5α.

Receptor epitopes for the Afa/Dr family of adhesins are conserved on the molecular form of CD55 present on PMNs (46). Previous studies have shown that the number, distribution, and accessibility of CD55 molecules on PMNs are sufficient to support adherence by Afa/Dr adhesin-positive bacteria (35). Moreover, PMNs express several heavily glycosylated CEACAM-related gly- coproteins, including CD66a (CEACAM1), CD66b (CEACAM8; CEA gene family member 6 [CGM6]), CD66c (CEACAM6), and CD66d (CEACAM3; CGM1) antigens (7, 28, 49, 58, 59), and at least two of them (CD66a and CD66c) have recently been implicated as receptors for Afa/Dr DAEC (8). In the present study, we demonstrated that increased caspase activity induced by Afa/Dr strains in PMNs is independent of CD55 and/or CD66a and CD66c. In PMNs, both Fas and FasL are constitutively expressed at the cell surface and therefore can induce cell death by both an autocrine and a paracrine mechanism (17, 40), although previous studies suggested that spontaneous PMN death occurs independently of Fas-mediated signaling (18). Moreover, an elevated density of PMNs and/or increased contact between PMNs can be associated with an increased rate of spontaneous neutrophil apoptosis (27). Since Afa/Dr DAEC strains triggered PMN agglutination, we sought to determine whether an increased rate of apoptosis observed in PMNs incubated with Afa/Dr DAEC strains was linked to this agglutination process. Interestingly, in a previous study, Johnson et al. reported that PMN agglutination induced by strain IH11128, but not strain C1845, was inhibited by chloramphenicol (35). These observations were in agreement with the fact that among the Afa/Dr adhesins, only the Dr adhesin-promoted events were inhibited by chlormaphenicol (13, 62) Our experiments confirmed and extended those of Johnson et al., since we found an excellent correlation between agglutination and caspase activation in PMNs infected with Afa/Dr DAEC strains on one hand and the effect of chloramphenicol on the other hand, strongly suggesting that agglutination is required for Afa/Dr DAEC-induced caspase activation. In view of these results, we next speculated that during Afa/Dr DAEC infection, induced PMN agglutination could increase Fas-FasL interaction between PMNs, leading to an elevated rate of cell apoptosis. However, pretreatment of PMNs with both anti-FasL and anti-Fas antibodies failed to decrease the rate of PMN apoptosis induced by infection with strain IH11128 (data not shown).

Most bacteria are rapidly phagocytosed when they interact with professional phagocytes. In PMNs, this phagocytic function is mediated mainly by complement receptor type III or by the Fc receptors (25). However, previous works have demonstrated that some bacteria, such as enteropathogenic E. coli (24), Yersinia pseudotuberculosis (5), Haemophilus ducreyi (63), Staphylococcus aureus (1), Enterococcus faecium (6), Brucella melitensis (20), and Helicobacter pylori (4, 55), can inhibit and/or delay neutrophil- or macrophage-mediated phagocytosis. To explain such inhibition, several pathogenic mechanisms have been postulated, involving, for example, the enteropathogenic E. coli-induced tyrosine dephosphorylation of several host proteins (24) or the type IV secretion system encoded by the cag pathogenicity island of H. pylori (4, 55). It was demonstrated in a previous study that engulfment of E. coli strain HMS174 after transmigration of PMNs across a cultured intestinal epithelium was significantly increased compared to nontransmigrated PMNs (31). Thus, we speculated that the phagocytosis capacity of PMNs once they migrated into the digestive lumen could be potentialized. In contrast to the results using strain HMS174, we showed here that Afa/Dr DAEC phagocytosis by transmigrated PMNs was not increased compared to that by nontransmigrated PMNs. In parallel, the PMN apoptotic rate was not altered in transmigrated PMNs incubated with Afa/Dr DAEC strains, whereas the PMN apoptotic rate was significantly decreased in transmigrated PMNs incubated with the control strain DH5α. Further studies are needed to determine by which mechanism Afa/Dr DAEC strains inhibit PMN-mediated phagocytosis.

In conclusion, our results suggest that Afa/Dr DAEC strains may increase their virulence during the infectious process through Afa/Dr adhesin-dependent interaction with PMNs by inducing a high apoptotic rate in PMNs and by decreasing PMN-mediated phagocytosis.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mireille Mari for her excellent technical assistance in electron microscopy, Pierrette Lapeyre for her excellent technical assistance in neutrophil isolation, and Agnes Loubat for her excellent technical assistance in flow cytometry analysis.

This work was supported by grants from the Fondation de France (P.H.) and the Ligue Nationale contre le Cancer (no. GLVP4259) (P.B.).

Editor: A. D. O'Brien

REFERENCES

- 1.Aarestrup, F. M., N. L. Scott, and L. M. Sordillo. 1994. Ability of Staphylococcus aureus coagulase genotypes to resist neutrophil bactericidal activity and phagocytosis. Infect. Immun. 62:5679-5682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aga, E., D. M. Katschinski, G. van Zandbergen, H. Laufs, B. Hansen, K. Muller, W. Solbach, and T. Laskay. 2002. Inhibition of the spontaneous apoptosis of neutrophil granulocytes by the intracellular parasite Leishmania major. J. Immunol. 169:898-905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aleman, M., A. Garcia, M. A. Saab, S. S. De La Barrera, M. Finiasz, E. Abbate, and M. C. Sasiain. 2002. Mycobacterium tuberculosis-induced activation accelerates apoptosis in peripheral blood neutrophils from patients with active tuberculosis. Am. J. Respir. Cell. Mol. Biol. 27:583-592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Allen, L. A., L. S. Schlesinger, and B. Kang. 2000. Virulent strains of Helicobacter pylori demonstrate delayed phagocytosis and stimulate homotypic phagosome fusion in macrophages. J. Exp. Med. 191:115-128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andersson, K., N. Carballeira, K. E. Magnusson, C. Persson, O. Stendahl, H. Wolf-Watz, and M. Fallman. 1996. YopH of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis interrupts early phosphotyrosine signalling associated with phagocytosis. Mol. Microbiol. 20:1057-1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arduino, R. C., K. Jacques-Palaz, B. E. Murray, and R. M. Rakita. 1994. Resistance of Enterococcus faecium to neutrophil-mediated phagocytosis. Infect. Immun. 62:5587-5594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beauchemin, N., P. Draber, G. Dveksler, P. Gold, S. Gray-Owen, F. Grunert, S. Hammarstrom, K. V. Holmes, A. Karlsson, M. Kuroki, S. H. Lin, L. Lucka, S. M. Najjar, M. Neumaier, B. Obrink, J. E. Shively, K. M. Skubitz, C. P. Stanners, P. Thomas, J. A. Thompson, M. Virji, S. von Kleist, C. Wagener, S. Watt, and W. Zimmermann. 1999. Redefined nomenclature for members of the carcinoembryonic antigen family. Exp. Cell Res. 252:243-249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berger, C. D., O. Bilker, T. F. Meyer, A. L. Servin, and I. Kansau. 2004. Differential recognition of members of the carcinoembryonic antigen family by Afa/Dr adhesins of diffusely adhering Escherichia coli (Afa/Dr DAEC). Mol. Microbiol. 52:963-983. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Bernet-Camard, M. F., M. H. Coconnier, S. Hudault, and A. L. Servin. 1996. Pathogenicity of the diffusely adhering strain Escherichia coli C1845:F1845 adhesin-decay accelerating factor interaction, brush border microvillus injury, and actin disassembly in cultured human intestinal epithelial cells. Infect. Immun. 64:1918-1928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Betis, F., P. Brest, V. Hofman, J. Guignot, M. F. Bernet-Camard, B. Rossi, A. Servin, and P. Hofman. 2003. The Afa/Dr adhesins of diffusely adhering Escherichia coli stimulate interleukin-8 secretion, activate mitogen-activated protein kinases, and promote polymorphonuclear transepithelial migration in T84 polarized epithelial cells. Infect. Immun. 71:1068-1074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Betis, F., P. Brest, V. Hofman, J. Guignot, I. Kansau, B. Rossi, A. Servin, and P. Hofman. 2003. Afa/Dr diffusely adhering Escherichia coli infection in T84 cell monolayers induces increased neutrophil transepithelial migration, which in turn promotes cytokine-dependent upregulation of decay-accelerating factor (CD55), the receptor for Afa/Dr adhesins. Infect. Immun. 71:1774-1783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bilge, S. S., C. R. Clausen, W. Lau, and S. L. Moseley. 1989. Molecular characterization of a fimbrial adhesin, F1845, mediating diffuse adherence of diarrhea-associated Escherichia coli to HEp-2 cells. J. Bacteriol. 171:4281-4289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carnoy, C., and S. L. Moseley. 1997. Mutational analysis of receptor binding mediated by the Dr family of Escherichia coli adhesins. Mol. Microbiol. 23:365-379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Colotta, F., F. Re, N. Polentarutti, S. Sozzani, and A. Mantovani. 1992. Modulation of granulocyte survival and programmed cell death by cytokines and bacterial products. Blood 80:2012-2020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cookson, S. T., and J. P. Nataro. 1996. Characterization of HEp-2 cell projection formation induced by diffusely adherent Escherichia coli. Microb. Pathog. 21:421-434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cravioto, A., A. Tello, A. Navarro, J. Ruiz, H. Villafan, F. Uribe, and C. Eslava. 1991. Association of Escherichia coli HEp-2 adherence patterns with type and duration of diarrhoea. Lancet 337:262-264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Druilhe, A., Z. Cai, S. Haile, S. Chouaib, and M. Pretolani. 1996. Fas-mediated apoptosis in cultured human eosinophils. Blood 87:2822-2830. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fecho, K., and P. L. Cohen. 1998. Fas ligand (gld)- and Fas (lpr)-deficient mice do not show alterations in the extravasation or apoptosis of inflammatory neutrophils. J. Leukoc. Biol. 64:373-383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fernandez-Prada, C., B. D. Tall, S. E. Elliott, D. L. Hoover, J. P. Nataro, and M. M. Venkatesan. 1998. Hemolysin-positive enteroaggregative and cell-detaching Escherichia coli strains cause oncosis of human monocyte-derived macrophages and apoptosis of murine J774 cells. Infect. Immun. 66:3918-3924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fernandez-Prada, C. M., E. B. Zelazowska, M. Nikolich, T. L. Hadfield, R. M. Roop II, G. L. Robertson, and D. L. Hoover. 2003. Interactions between Brucella melitensis and human phagocytes: bacterial surface O-polysaccharide inhibits phagocytosis, bacterial killing, and subsequent host cell apoptosis. Infect. Immun. 71:2110-2119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Foxman, B., L. Zhang, K. Palin, P. Tallman, and C. F. Marrs. 1995. Bacterial virulence characteristics of Escherichia coli isolates from first-time urinary tract infection. J. Infect. Dis. 171:1514-1521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Giron, J. A., T. Jones, F. Millan-Velasco, E. Castro-Munoz, L. Zarate, J. Fry, G. Frankel, S. L. Moseley, B. Baudry, J. B. Kaper, et al. 1991. Diffuse-adhering Escherichia coli (DAEC) as a putative cause of diarrhea in Mayan children in Mexico. J. Infect. Dis. 163:507-513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Glasser, A. L., J. Boudeau, N. Barnich, M. H. Perruchot, J. F. Colombel, and A. Darfeuille-Michaud. 2001. Adherent invasive Escherichia coli strains from patients with Crohn's disease survive and replicate within macrophages without inducing host cell death. Infect. Immun. 69:5529-5537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goosney, D. L., J. Celli, B. Kenny, and B. B. Finlay. 1999. Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli inhibits phagocytosis. Infect. Immun. 67:490-495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Greenberg, S., and S. Grinstein. 2002. Phagocytosis and innate immunity. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 14:136-145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guignot, J., I. Peiffer, M. F. Bernet-Camard, D. M. Lublin, C. Carnoy, S. L. Moseley, and A. L. Servin. 2000. Recruitment of CD55 and CD66e brush border-associated glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored proteins by members of the Afa/Dr diffusely adhering family of Escherichia coli that infect the human polarized intestinal Caco-2/TC7 cells. Infect. Immun. 68:3554-3563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hannah, S., K. Mecklenburgh, I. Rahman, G. J. Bellingan, A. Greening, C. Haslett, and E. R. Chilvers. 1995. Hypoxia prolongs neutrophil survival in vitro. FEBS Lett. 372:233-237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hofman, P. 2004. Molecular regulation of neutrophil apoptosis and potential targets for therapeutic strategy against the inflammatory process. Curr. Drug Targets Inflamm. Allerg. 3:1-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hofman, P. 2003. Pathological interactions of bacteria and toxins with the gastrointestinal epithelial tight junctions and/or the zonula adherens: an update. Cell. Mol. Biol. 49:65-75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hofman, P., L. D'Andrea, D. Carnes, S. P. Colgan, and J. L. Madara. 1996. Intestinal epithelial cytoskeleton selectively constrains lumen-to-tissue migration of neutrophils. Am. J. Physiol. 271:C312-C320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hofman, P., M. Piche, D. F. Far, G. Le Negrate, E. Selva, L. Landraud, A. Alliana-Schmid, P. Boquet, and B. Rossi. 2000. Increased Escherichia coli phagocytosis in neutrophils that have transmigrated across a cultured intestinal epithelium. Infect. Immun. 68:449-455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hofman, V., V. Ricci, B. Mograbi, P. Brest, F. Luciano, P. Boquet, B. Rossi, P. Auberger, and P. Hofman. 2001. Helicobacter pylori lipopolysaccharide hinders polymorphonuclear leucocyte apoptosis. Lab. Investig. 81:375-384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jallat, C., V. Livrelli, A. Darfeuille-Michaud, C. Rich, and B. Joly. 1993. Escherichia coli strains involved in diarrhea in France: high prevalence and heterogeneity of diffusely adhering strains. J. Clin. Microbiol. 31:2031-2037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Johnson, J. R. 1991. Virulence factors in Escherichia coli urinary tract infection. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 4:80-128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Johnson, J. R., K. M. Skubitz, B. J. Nowicki, K. Jacques-Palaz, and R. M. Rakita. 1995. Nonlethal adherence to human neutrophils mediated by Dr antigen-specific adhesins of Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 63:309-316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kaper, J. B., J. P. Nataro, and H. L. Mobley. 2004. Pathogenic Escherichia coli. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2:123-140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Labigne-Roussel, A., and S. Falkow. 1988. Distribution and degree of heterogeneity of the afimbrial-adhesin-encoding operon (afa) among uropathogenic Escherichia coli isolates. Infect. Immun. 56:640-648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Le Bouguenec, C., M. I. Garcia, V. Ouin, J. M. Desperrier, P. Gounon, and A. Labigne. 1993. Characterization of plasmid-borne afa-3 gene clusters encoding afimbrial adhesins expressed by Escherichia coli strains associated with intestinal or urinary tract infections. Infect. Immun. 61:5106-5114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee, A., M. K. Whyte, and C. Haslett. 1993. Inhibition of apoptosis and prolongation of neutrophil functional longevity by inflammatory mediators. J. Leukoc. Biol. 54:283-288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Le'Negrate, G., P. Rostagno, P. Auberger, B. Rossi, and P. Hofman. 2003. Downregulation of caspases and Fas ligand expression, and increased lifespan of neutrophils after transmigration across intestinal epithelium. Cell Death Differ. 10:153-162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lublin, D. M., and J. P. Atkinson. 1989. Decay-accelerating factor: biochemistry, molecular biology, and function. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 7:35-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lundqvist-Gustafsson, H., and T. Bengtsson. 1999. Activation of the granule pool of the NADPH oxidase accelerates apoptosis in human neutrophils. J. Leukoc. Biol. 65:196-204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Madara, J. L., S. Colgan, A. Nusrat, C. Delp, and C. Parkos. 1992. A simple approach to measurement of electrical parameters of cultured epithelial monolayers: use in assessing neutrophil epithelial monolayers transmigration. J. Tissue Cult. Methods 14:209-216. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Medeiros, A. I., V. L. Bonato, A. Malheiro, A. R. Dias, C. L. Silva, and L. H. Faccioli. 2002. Histoplasma capsulatum inhibits apoptosis and Mac-1 expression in leucocytes. Scand. J. Immunol. 56:392-398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Moulding, D. A., C. Walter, C. A. Hart, and S. W. Edwards. 1999. Effects of staphylococcal enterotoxins on human neutrophil functions and apoptosis. Infect. Immun. 67:2312-2318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nicholson-Weller, A., J. P. March, C. E. Rosen, D. B. Spicer, and K. F. Austen. 1985. Surface membrane expression by human blood leukocytes and platelets of decay-accelerating factor, a regulatory protein of the complement system. Blood 65:1237-1244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nowicki, B., J. Moulds, R. Hull, and S. Hull. 1988. A hemagglutinin of uropathogenic Escherichia coli recognizes the Dr blood group antigen. Infect. Immun. 56:1057-1060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nowicki, B., C. Svanborg-Eden, R. Hull, and S. Hull. 1989. Molecular analysis and epidemiology of the Dr hemagglutinin of uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 57:446-451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Obrink, B. 1997. CEA adhesion molecules: multifunctional proteins with signal-regulatory properties. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 9:616-626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Peiffer, I., A. B. Blanc-Potard, M. F. Bernet-Camard, J. Guignot, A. Barbat, and A. L. Servin. 2000. Afa/Dr diffusely adhering Escherichia coli C1845 infection promotes selective injuries in the junctional domain of polarized human intestinal Caco-2/TC7 cells. Infect. Immun. 68:3431-3442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Peiffer, I., J. Guignot, A. Barbat, C. Carnoy, S. L. Moseley, B. J. Nowicki, A. L. Servin, and M. F. Bernet-Camard. 2000. Structural and functional lesions in brush border of human polarized intestinal Caco-2/TC7 cells infected by members of the Afa/Dr diffusely adhering family of Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 68:5979-5990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Peiffer, I., A. L. Servin, and M. F. Bernet-Camard. 1998. Piracy of decay-accelerating factor (CD55) signal transduction by the diffusely adhering strain Escherichia coli C1845 promotes cytoskeletal F-actin rearrangements in cultured human intestinal INT407 cells. Infect. Immun. 66:4036-4042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Perskvist, N., M. Long, O. Stendahl, and L. Zheng. 2002. Mycobacterium tuberculosis promotes apoptosis in human neutrophils by activating caspase-3 and altering expression of Bax/Bcl-xL via an oxygen-dependent pathway. J. Immunol. 168:6358-6365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pham, T., A. Kaul, A. Hart, P. Goluszko, J. Moulds, S. Nowicki, D. M. Lublin, and B. J. Nowicki. 1995. dra-related X adhesins of gestational pyelonephritis-associated Escherichia coli recognize SCR-3 and SCR-4 domains of recombinant decay-accelerating factor. Infect. Immun. 63:1663-1668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ramarao, N., S. D. Gray-Owen, S. Backert, and T. F. Meyer. 2000. Helicobacter pylori inhibits phagocytosis by professional phagocytes involving type IV secretion components. Mol. Microbiol. 37:1389-1404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rotstein, D., J. Parodo, R. Taneja, and J. C. Marshall. 2000. Phagocytosis of Candida albicans induces apoptosis of human neutrophils. Shock 14:278-283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Scaletsky, I. C., M. L. Silva, and L. R. Trabulsi. 1984. Distinctive patterns of adherence of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli to HeLa cells. Infect. Immun. 45:534-536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Skubitz, K. M., K. D. Campbell, and A. P. Skubitz. 1996. CD66a, CD66b, CD66c, and CD66d each independently stimulate neutrophils. J. Leukoc. Biol. 60:106-117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Stocks, S. C., M. H. Ruchaud-Sparagano, M. A. Kerr, F. Grunert, C. Haslett, and I. Dransfield. 1996. CD66: role in the regulation of neutrophil effector function. Eur. J. Immunol. 26:2924-2932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ventur, Y., J. Scheffer, J. Hacker, W. Goebel, and W. Konig. 1990. Effects of adhesins from mannose-resistant Escherichia coli on mediator release from human lymphocytes, monocytes, and basophils and from polymorphonuclear granulocytes. Infect. Immun. 58:1500-1508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Watson, R. W., H. P. Redmond, J. H. Wang, C. Condron, and D. Bouchier-Hayes. 1996. Neutrophils undergo apoptosis following ingestion of Escherichia coli. J. Immunol. 156:3986-3992. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Westerlund, B., and T. K. Korhonen. 1993. Bacterial proteins binding to the mammalian extracellular matrix. Mol. Microbiol. 9:687-694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wood, G. E., S. M. Dutro, and P. A. Totten. 2001. Haemophilus ducreyi inhibits phagocytosis by U-937 cells, a human macrophage-like cell line. Infect. Immun. 69:4726-4733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yamamoto, A., S. Taniuchi, S. Tsuji, M. Hasui, and Y. Kobayashi. 2002. Role of reactive oxygen species in neutrophil apoptosis following ingestion of heat-killed Staphylococcus aureus. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 129:479-484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zychlinsky, A., and P. J. Sansonetti. 1997. Apoptosis as a proinflammatory event: what can we learn from bacteria-induced cell death? Trends Microbiol. 5:201-204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]