Abstract

Strategies to optimize formulations of multisubunit malaria vaccines require a basic knowledge of underlying protective immune mechanisms induced by each vaccine component. In the present study, we evaluated the contribution of antibody-mediated and cell-mediated immune mechanisms to the protection induced by immunization with two blood-stage malaria vaccine candidate antigens, apical membrane antigen 1 (AMA-1) and merozoite surface protein 1 (MSP-1). Immunologically intact or selected immunologic knockout mice were immunized with purified recombinant Plasmodium chabaudi AMA-1 (PcAMA-1) and/or the 42-kDa C-terminal processing fragment of P. chabaudi MSP-1 (MSP-142). The efficacy of immunization in each animal model was measured as protection against blood-stage P. chabaudi malaria. Immunization of B-cell-deficient JH−/− mice indicated that PcAMA-1 vaccine-induced immunity is largely antibody dependent. In contrast, JH−/− mice immunized with PcMSP-142 were partially protected against P. chabaudi malaria, indicating a role for protective antibody-dependent and antibody-independent mechanisms of immunity. The involvement of γδ T cells in vaccine-induced PcAMA-1 and/or PcMSP-142 protection was minor. Analysis of the isotypic profile of antigen-specific antibodies induced by immunization of immunologically intact mice revealed a dominant IgG1 response. However, neither interleukin-4 and the production of IgG1 antibodies nor gamma interferon and the production of IgG2a/c antibodies were essential for PcAMA-1 and/or PcMSP-142 vaccine-induced protection. Therefore, for protective antibody-mediated immunity, vaccine adjuvants and delivery systems for AMA-1- and MSP-1-based vaccines can be selected for their ability to maximize responses irrespective of IgG isotype or any Th1 versus Th2 bias in the CD4+-T-cell response.

In spite of the efforts of many governments and in the face of tremendous scientific advancement, the global burden of malaria is as great as it has ever been. It is estimated that as many as 500 million clinical cases of malaria result in 2.5 to 3.0 million deaths each year (6). The most realistic approach to reduce morbidity and mortality due to Plasmodium falciparum malaria is to develop safe and effective drugs and vaccines to treat and/or prevent malaria. Extensive and ongoing studies using humans and animal models indicate that protective immunity against malaria parasites develops (35, 36). The challenge is to develop multicomponent vaccines that induce protective immune responses that are broadly effective against geographically distinct strains of the malarial parasite.

A clear understanding of the immune responses that cooperate to suppress malaria parasite growth in the infected host is critical for the vaccine development effort. Parasite-specific antibodies, CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, and γδ T cells contribute to protection against infective sporozoites and parasites that initially develop in hepatocytes (27). Cell-mediated immune responses against these liver-stage parasites are particularly important. Parasite-specific antibodies, CD4+ T cells, and γδ T cells also contribute to protection against blood-stage malaria parasites (35, 40, 46). In this case, antibody-mediated immune responses may play the predominant role in protection. Of importance, the production of Th1-type cytokines appears to play a central role in the protective response to both pre-erythrocytic-stage and blood-stage malaria parasites and may involve the synthesis of gamma interferon (IFN-γ) by NK cells, γδ T cells, CD4+ T cells, or CD8+ T cells. To some extent, the beneficial influence of IFN-γ on antibody production has also been observed, as a number of studies have correlated protection with elevated levels of parasite-specific immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1) and IgG3 in humans (4, 20) and IgG2a/c in mice (53).

By utilizing various screening strategies, a number of plasmodial antigens have been identified as targets of protective immune responses and may be potentially useful as vaccine components (37). This number will likely increase over time as a result of the sequence analysis of the P. falciparum (18) and Plasmodium yoelii genomes (8). Concurrently, extensive efforts have been made to develop and test a variety of platforms, delivery systems, adjuvants, and immunization protocols for malaria subunit vaccines. Clinical trials of candidate malaria vaccines have met with some limited success (19). A continued effort is needed, and additional vaccine trials are ongoing. One impediment in this effort has been the inability to define suitable immune correlates of protection that can be measured and used to optimize vaccine formulations and immunization protocols.

The rodent malarial parasite Plasmodium chabaudi is a useful tool in this effort to develop and test blood-stage malaria vaccines. In previous work, the P. chabaudi model was used extensively to characterize infection-induced immune mechanisms effective against blood-stage parasites (35, 46). From these studies, it became clear that it is possible to separately measure the protective antibody-mediated immune response (AMI) or the protective γδ and CD4+-T-cell-mediated immune response (CMI) against P. chabaudi by using mice made to be deficient in immunity by antibody depletion and/or targeted gene knockout (21, 46-48, 50, 52). Furthermore, it was also shown that in naïve mice, the production of IFN-γ is critical for the suppression of P. chabaudi malaria by either AMI or CMI (3, 42, 49). The synthesis of interleukin-4 (IL-4) late during P. chabaudi malaria has also been reported and is believed to contribute to the production of parasite-specific antibodies necessary for final parasite clearance (31, 41).

The two leading P. falciparum blood-stage vaccine candidate antigens are apical membrane antigen 1 (AMA-1) and merozoite surface protein 1 (MSP-1). These two merozoite surface proteins have been extensively studied using several species of Plasmodium, and their vaccine potential has been plainly demonstrated (26, 29). Well-characterized orthologues of P. falciparum AMA-1 (PfAMA-1) and MSP-1 (PfMSP-1) are present in P. chabaudi (PcAMA-1 and PcMSP-1) (11, 15, 32, 34). Furthermore, we and others have shown that immunization with recombinant PcAMA-1 and/or PcMSP-1 protects against P. chabaudi malaria (2, 7, 11, 39). In the present study, we extend previous efforts to evaluate the efficacy of immunization with vaccines based on PcAMA-1 and the 42-kDa C-terminal processing fragment of PcMSP-1 (PcMSP-142) (7) to further define immune correlates of protection. Herein, we utilize gene-targeted knockout mice to evaluate the importance of AMI and CMI to immunity induced by immunization with PcAMA-1 and/or PcMSP-142 and the dependence of the protective response on IFN-γ, IL-4, and IgG subclasses.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice, malaria parasites, and experimental infections.

C57BL/6J mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, Maine). Likewise, γδ T-cell-receptor-deficient (TCR-δ−/−), IFN-γ−/−, and IL-4−/− mice, backcrossed to C57BL/6 mice for at least 10 generations, were purchased from Jackson Laboratories. TCR-δ−/− mice have a targeted deletion of the genes for the δ chain of the T-cell receptor and fail to develop populations of T cells bearing γδ receptors (25). The IFN-γ−/− and IL-4−/− mice are unable to produce IFN-γ and IL-4, respectively, due to targeted disruptions of the corresponding cytokine genes (12, 28). B-cell-deficient JH−/− mice on a C57BL/6 × 129 background were kindly provided by Dennis Huszar (GenPharm International, Mountain View, Calif.). These JH−/− mice fail to produce mature surface Ig-positive B cells due to the targeted deletion of Ig heavy chain J gene segments (9). TCR-δ−/− and JH−/− mice were bred at the University of Wisconsin Animal Care Facilities (Madison, Wis.) in microisolator cages and provided with sterile food and water ad libitum. Routine screenings of sentinel mice were conducted throughout these studies to ensure that animals remained free of infection with common viral and bacterial pathogens.

Mice of both sexes, 6 to 12 weeks of age, were used in all immunization and challenge experiments. P. chabaudi adami 556KA, hereafter referred to as P. chabaudi, was maintained as cryopreserved stabilates. Blood-stage infections were initiated by intraperitoneal injection of 106 washed, parasitized erythrocytes obtained from BALB/c donor mice. Resulting parasitemias were monitored by enumerating parasitized red blood cells in thin tail blood smears stained with Giemsa stain.

Expression and purification of recombinant PcAMA-1 and PcMSP-142.

The expression and purification of recombinant PcAMA-1 and PcMSP-142 from P. chabaudi have been previously described in detail (7). Briefly, recombinant antigens were produced by using a pET/T7 RNA polymerase bacterial expression system with the pET-15b plasmid vector and Escherichia coli BL21(DE3)(pLysS) as the host strain (Novagen, Madison, Wis.). A 54-kDa recombinant PcAMA-1 protein that represented the large ectodomain of P. chabaudi AMA-1 (amino acids 26 to 479) was expressed. The recombinant PcMSP-142 antigen contained the C-terminal portion of MSP-1 but lacked the hydrophobic anchor sequence. Both recombinant antigens contained 20 plasmid-encoded N-terminal amino acids which included a six-histidine tag to facilitate purification. Following isolation and solubilization of the inclusion body fraction, PcAMA-1 and PcMSP-142 were purified by ammonium sulfate fractionation and nickel chelate affinity chromatography under denaturing conditions. PcAMA-1 and PcMSP-142 were refolded by gradual removal of guanidine-HCl by dialysis in the presence of reduced and oxidized glutathione. Protein concentrations were determined by using the bicinchoninic acid protein assay (Pierce Chemical Company, Rockford, Ill.). The purity of recombinant PcAMA-1 and PcMSP-142 preparations was assessed by Coomassie blue staining following sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis under reducing and nonreducing conditions.

Immunization and challenge protocols.

A single immunization protocol was used for all immunogenicity and efficacy studies. Groups (n = 5) of immunologically intact C57BL/6J mice or immunodeficient knockout mice were immunized subcutaneously with 25 μg of purified recombinant PcAMA-1 or PcMSP-142 with 25 μg of Quil A (Accurate Chemical and Scientific Corporation, Westbury, N.Y.) as adjuvant. An additional group of mice was immunized with a combination of PcAMA-1 (25 μg) and PcMSP-142 (25 μg) similarly formulated with Quil A. Control animals were immunized with Quil A alone or saline. Three weeks following the primary immunization, animals were boosted with the same doses of antigen and adjuvant. Eight to 10 days later, small volumes of prechallenge sera for antibody assays were collected. Approximately 10 to 14 days following the booster immunization, mice were infected intraperitoneally with 106 P. chabaudi-parasitized erythrocytes, and blood parasitemias were monitored. The statistical significance of differences in mean peak parasitemia between groups was calculated by analysis of variance using the StatMost statistical analysis software package (Data Most Corp., Salt Lake City, Utah). For comparison purposes, note that the mean peak parasitemias in saline and adjuvant control TCR-δ−/−, JH−/−, and IL-4−/− mice are not statistically different than those obtained with intact C57BL/6 mice. The data presented on the responses of C57BL/6, TCR-δ−/−, JH−/−, and IFN-γ−/− mice were obtained from concurrently immunized and challenged groups of mice.

IgG isotype ELISA.

The quantity and isotypic profile of antigen-specific antibodies in prechallenge sera were determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) as previously described using recombinant PcAMA-1- or PcMSP-142-coated wells (7). Serum from each animal per group (n = 5) was assayed on antigen-coated wells at dilutions of 1:200, 1:1,000, 1:10,000, 1:100,000, and 1:1,000,000. Antigen-specific antibodies were detected with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated rabbit antibody specific for mouse IgG1, IgG2b, or IgG3 (Zymed Laboratories, San Francisco, Calif.) or with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG2c (IgG2a b allotype; Southern Biotechnology Associates, Inc., Birmingham, Ala.) (33) and ABTS [2,2′-azinobis(3-ethylbenzthiazolinesulfonic acid)] as the substrate. Serum samples were run in duplicate, and absorbance was read at 405 nm. In each assay, wells coated with purified IgG1, IgG2b, or IgG3 myeloma proteins (16 ng/ml to 1 μg/ml; Zymed Laboratories) were used to generate a standard curve. The IgG2a/c standard curve was generated by using a purified monoclonal IgG2c (IgG2a b allotype) antibody (BD Biosciences Pharmingen). The isotype standard curves were used to quantitate antigen-specific antibody present in each serum sample with the dilution of serum that yielded an optical density at 405 nm of between 0.1 and 1.0. The concentration of IgG isotype was expressed in units per milliliter, where 1 U/ml was equivalent to 1 μg of myeloma standard/ml. Values obtained with adjuvant control sera (n = 5) were comparable to background values obtained with normal mouse sera (n = 5) and have been subtracted. The statistical significance of differences in mean IgG concentrations between groups was calculated by analysis of variance using the StatMost statistical analysis software package (Data Most Corp.).

RESULTS

Isotypic profile of antigen-specific IgG antibodies induced by protective immunization with PcAMA-1 and PcMSP-142.

To begin to characterize PcAMA-1- and PcMSP-142-induced protective responses, immunologically intact C57BL/6 mice were immunized with purified recombinant PcAMA-1, PcMSP-142, or a combination of PcAMA-1 and PcMSP-142 by using Quil A as adjuvant. All groups of mice received one booster immunization 3 weeks later with the same doses of antigen and adjuvant. Approximately 2 weeks later, a small volume of prechallenge serum was collected from each animal to determine the quantity and isotypic profile of PcAMA-1- or PcMSP-142-specific antibodies induced by immunization. The efficacy of immunization was evaluated following challenge infection with P. chabaudi-parasitized erythrocytes.

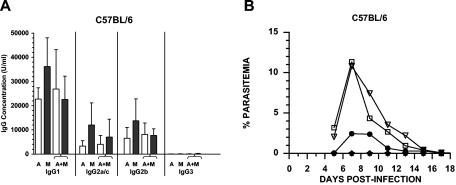

A dominant IgG1 response to PcAMA-1 and PcMSP-142 was observed following immunization with each antigen alone or with the antigen combination (Fig. 1A). Overall, the IgG1 response to both antigens was three- to sixfold higher than the IgG2a/c (P < 0.05) and the IgG2b (P < 0.05) responses. The IgG2a/c and IgG2b antibody levels were comparable. Very little antigen-specific IgG3 was induced by PcAMA-1 or PcMSP-142 immunization. In mice immunized with PcAMA-1 or PcMSP-142 alone, the anti-PcMSP-142 antibody concentrations were consistently greater than the concentrations of anti-PcAMA-1 antibodies with significant differences in antigen-specific total IgG (P < 0.05) and IgG1 (P < 0.05) production. For the combined antigen immunization, the PcAMA-1 antibody responses were essentially the same as those observed in mice immunized with PcAMA-1 alone. In contrast, there was a small but consistent drop in the anti-PcMSP-142 antibody response in the combined antigen immunization group. As a result, no significant differences were noted when the overall anti-PcAMA-1 and anti-PcMSP-142 antibody levels induced by immunization with the combined antigen formulation were compared.

FIG. 1.

Isotypic profile of antigen-specific IgG antibodies induced by protective immunization with recombinant PcAMA-1 and/or PcMSP-1. (A) Groups of C57BL/6 mice (n = 5) were immunized with recombinant PcAMA-1 (A), PcMSP-142 (M), or the combination of PcAMA-1 and PcMSP-142 (A+M) with Quil A as adjuvant. The concentrations of IgG1, IgG2a/c, IgG2b, and IgG3 antibodies specific for PcAMA-1 (white bars) or PcMSP-142 (black bars) present in prechallenge sera were determined by ELISA. Background values obtained when adjuvant control sera (n = 5) were used have been subtracted. (B) Groups of C57BL/6 mice (n = 5) immunized with purified recombinant PcAMA-1 (♦), PcMSP-1 (•), or PcAMA-1 plus PcMSP-1 (★) with Quil A as adjuvant were challenged with 106 P. chabaudi-parasitized erythrocytes. Mice immunized with Quil A alone (□) or phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) alone (▿) served as controls. Resulting parasitemias were monitored by enumerating parasitized erythrocytes in thin tail blood smears stained with Giemsa stain. The results obtained are similar to previously reported data (7).

Significant protection against P. chabaudi challenge infection was induced by PcMSP-142 immunization, with a fourfold reduction in mean peak parasitemia compared to those of the Quil A (P < 0.01) and saline (P < 0.01) control groups (Fig. 1B). The mean peak parasitemia in PcMSP-142-immunized mice was reduced to 3.05% ± 2.03% compared to 12.99% ± 6.32% and 12.48% ± 4.75% in adjuvant and saline control groups, respectively. Solid protection was also induced by immunization with PcAMA-1 compared to Quil A (P < 0.002) and saline (P < 0.001) control groups (Fig. 1B). Parasitemia levels remained below 0.01% in PcAMA-1-immunized mice throughout the course of infection. While the overall prechallenge anti-PcMSP-142 antibody levels were higher than anti-PcAMA-1 antibody levels, the reduction in parasitemia was significantly greater in PcAMA-1-immunized versus PcMSP-142-immunized mice (P < 0.01). This high level of protection was also evident in mice immunized with the combination of PcAMA-1 and PcMSP-142. Mean peak parasitemia in the combined antigen immunization group was 0.14% ± 0.26% and not significantly different than that induced by immunization with PcAMA-1 alone (Fig. 1B).

Protective AMI and CMI induced by PcAMA-1 and PcMSP-142 immunization.

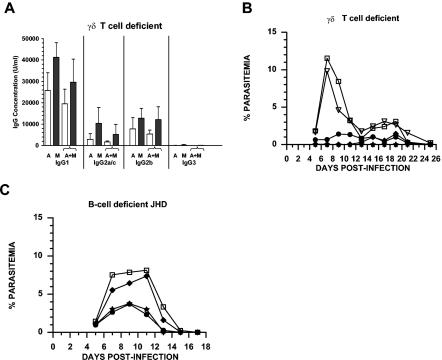

To assess the contribution of γδ T-cell-dependent cell-mediated immunity to PcAMA-1 and PcMSP-142 immunization-induced protection, TCR-δ−/− mice lacking γδ T cells were immunized with PcAMA-1 and/or PcMSP-142 as described above. Analysis of prechallenge sera reflected a strong B-cell response induced by PcAMA-1 and PcMSP-142 immunization in TCR-δ−/− mice (Fig. 2A), again characterized by the production of high levels of IgG1 antibodies. Considering both the quantity and isotypic profile of PcAMA-1 and PcMSP-142 antigen-specific antibodies, no significant differences were noted in the responses of TCR-δ−/− mice (Fig. 2A) and immunologically intact C57BL/6 mice (Fig. 1A).

FIG. 2.

Protective AMI and CMI induced by PcAMA-1 and PcMSP-142 immunization. (A) Groups of TCR-δ−/− mice (n = 5) were immunized with recombinant PcAMA-1 (A), PcMSP-142 (M), or the combination of PcAMA-1 and PcMSP-142 (A+M) with Quil A as adjuvant. The concentrations of IgG1, IgG2a/c, IgG2b, and IgG3 antibodies specific for PcAMA-1 (white bars) or PcMSP-142 (black bars) present in prechallenge sera were determined by ELISA. Background values obtained by using adjuvant control sera (n = 5) have been subtracted. (B and C) Groups of TCR-δ−/− mice (n = 5) (B) and JH−/− (JHD) mice (n = 5) (C) immunized with purified recombinant PcAMA-1 (♦), PcMSP-1 (•), or PcAMA-1 plus PcMSP-1 (★) with Quil A as adjuvant were challenged with 106 P. chabaudi-parasitized erythrocytes. Mice immunized with Quil A alone (□) or PBS alone (▿) served as controls. Resulting parasitemias were monitored by enumerating parasitized erythrocytes in thin tail blood smears stained with Giemsa stain. Similar protection data were obtained in studies of C57BL/6, TCR-δ−/−, and JH−/− mice immunized with PcAMA-1 and/or PcMSP-142 formulated with Freund's adjuvant and recombinant IL-12 in place of Quil A.

Upon P. chabaudi challenge infection, TCR-δ−/− mice immunized with PcAMA-1, PcMSP-142, or the combination of PcAMA-1 and PcMSP-142 were protected against P. chabaudi malaria (Fig. 2B). Overall, mean peak parasitemia in TCR-δ−/− mice immunized with single or combined antigen formulations was ≤2% and significantly reduced from 11.67% ± 4.13% in Quil A controls (P < 0.01) and 10.65% ± 5.60% in saline controls (P < 0.02). TCR-δ−/− mice immunized with PcAMA-1 developed a slightly higher mean peak parasitemia of 1.54% (± 1.86%) in comparison to PcAMA-1-immunized C57BL/6 mice in which parasitemia remained below 0.01%. In contrast to immunologically intact C57BL/6 mice, TCR-δ−/− mice immunized with PcAMA-1 and/or PcMSP-142 also developed a low level of parasitemia that persisted into the third week of P. chabaudi infection but was subsequently cleared (Fig. 2B). This low level of persistent parasitemia was also apparent in control TCR-δ−/− mice immunized with Quil A or saline alone. These data suggest that γδ T cells contribute to P. chabaudi parasite clearance in naïve and immunized mice. However, the contribution of γδ T cells specifically to PcAMA-1 and/or PcMSP-142 vaccine-induced protection using Quil A-based formulations appears to be minor.

To further evaluate the contribution of antibody-independent, cell-mediated immune mechanisms to PcAMA-1 and PcMSP-142 vaccine-induced protection, B-cell-deficient JH−/− mice were immunized with PcAMA-1 and/or PcMSP-142 as described above. As shown in Fig. 2C, protection induced by PcAMA-1 immunization was essentially lost in B-cell-deficient JH−/− mice. Mean peak parasitemia in PcAMA-1-immunized JH−/− mice was 8.10% ± 3.50% and was not statistically different (P > 0.05) from the mean peak parasitemia of 9.59% ± 3.82% for JH−/− adjuvant control mice. In contrast, partial protection against P. chabaudi malaria was induced by PcMSP-142 immunization in B-cell-deficient mice. PcMSP-142-immunized JH−/− mice developed a mean peak parasitemia approximately 2.5-fold lower than that observed in adjuvant control mice (3.91% ± 1.35% versus 9.59% ± 3.82%; P < 0.02). A comparable reduction in mean peak parasitemia was also observed in JH−/− mice immunized with both PcAMA-1 and PcMSP-142, with the mean peak parasitemia reaching 4.12% ± 1.74% (P < 0.02). The partial protection in JH−/− mice immunized with PcAMA-1 plus PcMSP-142 was not significantly different that that induced by immunization with PcMSP-142 alone. As such, these data suggest that both antibody-mediated and cell-mediated mechanisms of immunity contribute to protection against P. chabaudi malaria induced by PcMSP-142 and Quil A immunization. Conversely, protection induced by immunization with PcAMA-1 and Quil A is largely, if not completely, antibody mediated.

IFN-γ is not required for PcAMA-1 and PcMSP-142 vaccine-induced protection.

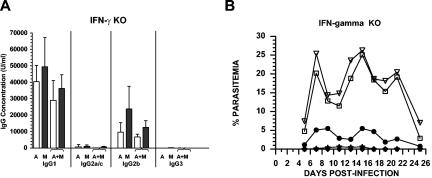

Studies of P. chabaudi infection using naïve mice indicate that IFN-γ is an important cytokine in the development of protective AMI and CMI against blood-stage parasites. Accordingly, IFN-γ-deficient mice were utilized to assess the importance of this cytokine for protection induced by PcAMA-1 and/or PcMSP-142 immunization. IFN-γ−/− knockout mice were immunized with PcAMA-1 and/or PcMSP-142 formulated with Quil A as adjuvant as described above. Analysis of prechallenge sera showed that the lack of IFN-γ significantly altered the isotypic profile of antibodies induced by PcAMA-1 and PcMSP-142 immunization. Following single or combined antigen immunization, the PcAMA-1- and PcMSP-142-specific IgG2a/c response was markedly reduced in IFN-γ−/− mice (Fig. 3A). However, with the decrease in IgG2a/c antibody levels, compensatory increases in IgG1 and/or IgG2b production were apparent. Consequently, the total level of PcAMA-1- and PcMSP-142-specific IgG induced by immunization in IFN-γ−/− mice was equal to or slightly greater than that induced in immunologically intact C57BL/6 mice (Fig. 1A).

FIG. 3.

IFN-γ is not required for PcAMA-1 and PcMSP-142 vaccine-induced protection. (A) Groups of IFN-γ−/− mice (n = 5) were immunized with recombinant PcAMA-1 (A), PcMSP-142 (M), or the combination of PcAMA-1 and PcMSP-142 (A+M) with Quil A as adjuvant. The concentration of IgG1, IgG2a/c, IgG2b, and IgG3 antibodies specific for PcAMA-1 (white bars) or PcMSP-142 (black bars) present in prechallenge sera were determined by ELISA. Background values obtained by using adjuvant control sera (n = 5) have been subtracted. (B) Groups of IFN-γ−/− mice (n = 5) immunized with purified recombinant PcAMA-1 (♦), PcMSP-1 (•), or PcAMA-1 plus PcMSP-1 (★) with Quil A as adjuvant were challenged with 106 P. chabaudi-parasitized erythrocytes. Mice immunized with Quil A alone (□) or PBS alone (▿) served as controls. Resulting parasitemias were monitored by enumerating parasitized erythrocytes in thin tail blood smears stained with Giemsa stain. Mean peak parasitemia in IFN-γ−/− mice immunized with Quil A or saline is significantly higher than that observed in immunologically intact C57BL/6 controls (P < 0.01). This finding is consistent with previously reported data (3, 49).

Upon P. chabaudi challenge infection of IFN-γ−/− mice, a more severe and prolonged infection in Quil A and saline controls developed, with mean peak parasitemias of 27.25% ± 3.44% and 27.76% ± 3.37%, respectively (Fig. 3B). Compared to this exacerbated P. chabaudi infection in naïve controls, parasitemia in immunized IFN-γ−/− mice was markedly reduced (P < 0.01) with mean peak parasitemias of 0.02% ± 0.04% in PcAMA-1 immunized mice, 8.29% ± 10.81% in PcMSP-142-immunized mice, and 0.61% ± 1.37% in mice immunized with PcAMA-1 plus PcMSP-142. Similar to previous observations of prolonged P. chabaudi infection in IFN-γ−/− mice (3, 49), a high level of parasitemia persisted in IFN-γ−/− control mice into the third and fourth week of P. chabaudi infection. During this same time period, parasitemia was controlled at low levels in PcAMA-1- and/or PcMSP-142-immunized IFN-γ−/− mice prior to final parasite clearance. These combined data indicated that neither the IFN-γ deficiency nor the impaired IgG2a/c antibody response significantly altered the efficacy of immunization with PcAMA-1 and/or PcMSP-142 formulated with Quil A as adjuvant.

IL-4 is not required for PcAMA-1 and PcMSP-142 vaccine-induced protection.

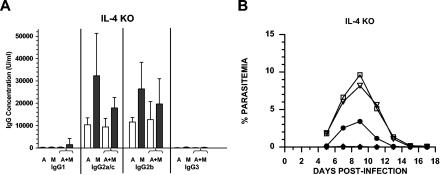

The dominant IgG1 response induced by PcAMA-1 and PcMSP-142 immunization suggested that IL-4 and the production of antigen-specific antibodies of this isotype may be necessary for vaccine-induced protection. To address this possibility, IL-4 knockout (IL-4−/−) mice were immunized with PcAMA-1 and/or PcMSP-142 formulated with Quil A as adjuvant and subsequently challenged with P. chabaudi blood-stage parasites. As expected, analysis of prechallenge sera showed a marked reduction in the production of IgG1 antibodies following PcAMA-1 and PcMSP-142 immunization (Fig. 4A). Antigen-specific IgG1 levels in PcAMA-1- and/or PcMSP-142-immunized IL-4−/− mice dropped 15- to 100-fold relative to immunologically intact controls (P < 0.01). Once again, compensatory responses were apparent as the production of antigen-specific IgG2a/c and/or IgG2b antibodies increased in IL-4−/− mice. The net result was that no significant differences in total antigen-specific IgG levels in IL-4−/− mice compared to C57BL/6 controls were indicated.

FIG. 4.

IL-4 is not required for PcAMA-1 and PcMSP-142 vaccine-induced protection. (A) Groups of IL-4−/− mice (n = 5) were immunized with recombinant PcAMA-1 (A), PcMSP-142 (M), or the combination of PcAMA-1 and PcMSP-142 (A+M) with Quil A as adjuvant. The concentration of IgG1, IgG2a/c, IgG2b, and IgG3 antibodies specific for PcAMA-1 (white bars) or PcMSP-142 (black bars) present in prechallenge sera were determined by ELISA. Background values obtained by using adjuvant control sera (n = 5) have been subtracted. (B) Groups of IL-4−/− mice (n = 5) immunized with purified recombinant PcAMA-1 (♦), PcMSP-1 (•), or PcAMA-1 plus PcMSP-1 (★) with Quil A as adjuvant were challenged with 106 P. chabaudi-parasitized erythrocytes. Mice immunized with Quil A alone (□) or PBS alone (▿) served as controls. Resulting parasitemias were monitored by enumerating parasitized erythrocytes in thin tail blood smears stained with Giemsa stain.

As shown in Fig. 4B, the efficacy of immunization of IL-4−/− mice with PcAMA-1 or PcMSP-142 was comparable to that observed with immunologically intact mice. Following P. chabaudi challenge infection, mean peak parasitemia in immunized animals was markedly reduced relative to controls (P < 0.01), reaching 0.06% ± 0.13% in the PcAMA-1 group and 3.96% ± 1.93% in the PcMSP-142 group compared to 9.63% ± 0.40% and 8.19% ± 2.47% in the Quil A and saline control groups, respectively. Throughout the course of P. chabaudi infection, blood parasitemia levels remained below 0.01% in IL-4−/− mice immunized with the combination of PcAMA-1 and PcMSP-142. These data suggest that the IL-4 deficiency and impaired production of antigen-specific IgG1 did not alter the protective response induced by immunization with PcAMA-1 and/or PcMSP-142 formulated with Quil A as adjuvant.

DISCUSSION

Strategies for malaria blood-stage vaccine development have focused on the construction and testing of vaccines based on target proteins expressed on the surface of either infected erythrocytes (i.e., erythrocyte membrane protein 1) or invasive merozoites (i.e., AMA-1 and MSP-1) that are antibody accessible (26, 29, 37). There is consensus in the field that for these vaccines, the adjuvants and delivery systems employed must promote the development of high titers of antibodies to achieve some measure of efficacy. There is also evidence that the isotype of parasite-specific IgG may be important in P. falciparum malaria. The production of cytophilic IgG1 and IgG3 (4, 20) and the contribution of these IgG isotypes to antibody-dependent cellular inhibition of P. falciparum blood-stage growth have been correlated with protection (5). Similar supporting data are evident from studies of P. yoelii and P. chabaudi which suggest that the production of cytophilic IgG2a/c is important for infection and/or immunization-induced protective responses (43, 44, 53). Clearly, it is expected that the relative importance of IgG isotype for protection will vary depending on the specific antigen and protective immune effector mechanisms involved. In conjunction with AMI, vaccine-induced CMI, the activation of γδ and CD4+ T cells, and the synthesis of IFN-γ may further enhance protective efficacy (35, 40, 46).

In the present study, we have experimentally manipulated responses induced by immunization with PcAMA-1 and PcMSP-142 and then measured protective efficacy against P. chabaudi malaria. In naïve mice, the resolution of acute P. chabaudi malaria requires IFN-γ and the expansion of parasite-specific CD4+ T cells. Downstream immune effector mechanisms may involve either γδ T cells or B-cell activation and the secretion of parasite-specific antibodies. The lack of protection following immunization of B-cell-deficient JH−/− mice with PcAMA-1 indicated that AMA-1 vaccine-induced immunity is antibody dependent. This finding is consistent with studies by Anders and colleagues which highlighted the importance of antibodies specific for disulfide-dependent epitopes of PcAMA-1 for protection (2). We did not see any evidence for an antibody-independent contribution of CD4+ T cells to PcAMA-1-induced protection as was previously suggested (55).

Extensive studies using humans and animal models have established the protective role of antibodies that recognize conformation-dependent B-cell epitopes associated with the C-terminal epidermal growth factor-like domains of MSP-119 (13, 17, 22, 26, 30). However, there appears to be a paucity of CD4+-T-cell epitopes associated with MSP-119 (16, 45). Undoubtedly, there are CD4+-T-cell epitopes associated with the 33-kDa fragment that is proteolytically cleaved from MSP-142 to yield MSP-119. The contribution of these T-cell epitopes to antibody-independent protective responses induced by MSP-142 immunization has been uncertain (1, 54). Our present data however, clearly show that PcMSP-142-immunized B-cell-deficient mice are partially protected against P. chabaudi malaria compared to PcMSP-142-immunized C57BL/6 controls (2.45-fold versus 4.25-fold reduction in mean peak parasitemia). These data support the conclusion that T-cell epitopes contained within PcMSP-142 can induce protective CMI in the context of recombinant antigen and Quil A immunization.

The production of IFN-γ during P. falciparum, P. chabaudi, and P. yoelii malaria has been shown to be important in the development of responses leading to the suppression of blood-stage parasitemia in nonimmunized hosts (27, 35, 36, 40, 46). In naïve animals infected with P. chabaudi, IFN-γ appears to be necessary for the development of both AMI and CMI and the suppression of acute blood-stage infection (3, 42, 49). The ability to completely clear P. chabaudi blood-stage parasites from circulation has been attributed to the production of IL-4 late during P. chabaudi malaria and enhanced AMI (31, 41). The importance of IFN-γ and IL-4 for immunization with blood-stage malaria vaccines has not been adequately addressed. Using immunologic knockout mice, we have shown that protection induced by immunization with PcAMA-1 and PcMSP-142, alone or in combination, is not strictly dependent on either IFN-γ or IL-4. While AMI is clearly important, protective antibody responses can be induced in the presence or absence of IFN-γ or IL-4. Because of this redundancy, vaccine adjuvants and delivery systems for AMA-1- and MSP-1-based vaccines should primarily be selected for their ability to maximize antibody responses irrespective of a Th1 or Th2 bias. This may be particularly important in order to minimize potentially pathological Th1-type proinflammatory responses (10). Furthermore, this ability to induce protective AMI by multiple pathways may also permit the development of MSP-142-based vaccines that effectively induce both antibody-dependent and antibody-independent immune mechanisms.

In general, immunization with PcMSP-142 induced higher antibody levels than those observed following immunization with PcAMA-1. In spite of this result, PcAMA-1-induced protection was consistently better than that induced by PcMSP-142 immunization. The protective PcAMA-1 response potentially involves antibodies specific for B-cell epitopes distributed across the three domains (domains I, II, and III) that define the conformationally constrained 54-kDa ectodomain of PcAMA-1 (24). In contrast, protective B-cell epitopes of MSP-142 are primarily restricted to the C-terminal epidermal growth factor-like domains (MSP-119). The advantage of using the larger PcMSP-142 recombinant antigen for immunization is that the additional parasite-specific T-cell epitopes included may (i) promote the boosting of PcMSP-1-specific antibody responses upon exposure to blood-stage parasites during infection and (ii) elicit protective cell-mediated responses. Unfortunately, the use of the larger PcMSP-142 antigen for immunization may induce high overall IgG levels but may not adequately focus the B-cell responses on the most protective C-terminal epitopes. Thus, the challenge will be to design MSP-1 vaccine constructs that more effectively promote the development and boosting of protective AMI and CMI to maximize efficacy.

A dominant antigen-specific IgG1 response in immunologically intact animals immunized with PcAMA-1 and/or PcMSP-142 was not unexpected considering previous data with Quil A as adjuvant (7). High IgG1 titers have also been observed in animals protectively immunized with Plasmodium yoelii MSP-119 (PyMSP-119) (14). However, it was not clear from these previous data if protection induced by PcAMA-1 and/or PcMSP-142 immunization required IgG1 or could be enhanced with increased production of IgG bearing other isotypes with different associated effector functions (i.e., IgG2a/c). Our data obtained from the immunization of IFN-γ−/− and IL-4−/− mice indicate that neither IgG1 nor IgG2a/c is essential for PcAMA-1- or PcMSP-142-induced protection. Furthermore, increased production of IgG2a/c and/or IgG2b antibodies can compensate for a lack of antigen-specific IgG1 but does not appear to significantly improve vaccine efficacy. Combined, these data suggest that protective AMI induced by immunization with PcAMA-1 and PcMSP-142 is IgG isotype independent and therefore does not likely require complement activation or Fc receptor-bearing cells. This is in agreement with previous data demonstrating that anti-PyMSP-119-mediated protection is unaffected by FcRγ or FcγRI receptor deletion (38, 51).

Considering the overall antibody data, no major competition between the two antigens was noted for animals immunized with the combination of PcAMA-1 and PcMSP-142. This finding is encouraging, as multiallelic formulations of PfAMA-1 and PfMSP-142 vaccines will be required. It also appears that the formulation of PfAMA-1 in combination with multiple antigens in various adjuvants should be reasonably straightforward as long as sufficient antibody responses are induced. On the other hand, immunization with PfMSP-142-based vaccines may require additional effort to optimize the induction of antibodies to the most protective epitopes while concurrently stimulating potentially protective cell-mediated responses. Our present data also suggest that IFN-γ-dependent and γδ T-cell-dependent responses contribute to parasite clearance in naïve as well as immunized mice. While the protection observed was statistically significant, we noted some variability in protection in PcMSP-142-immunized IFN-γ−/− mice that we could not clearly correlate with changes in antibody responses. This result may reflect an IFN-γ-dependent contribution to the CMI induced by PcMSP-142 immunization that is partially masked by the presence of antibody. However, it is also probable that other parasite antigens are targets of IFN-γ-dependent and γδ T-cell-dependent protective responses. In studies of PyMSP-119, Daly and Long (13) and Hirunpetcharat et al. (23) showed that additional infection-induced immune responses are necessary for final parasite clearance in actively or passively immunized animals. As such, it appears that it should be possible, and likely necessary, to formulate PfAMA-1- and PfMSP-142-based vaccines with additional plasmodial antigens in order to increase vaccine-induced protection against blood-stage malaria parasites.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH-NIAID grant AI49585.

Editor: W. A. Petri, Jr.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahlborg, N., I. T. Ling, W. Howard, A. A. Holder, and E. M. Riley. 2002. Protective immune responses to the 42-kilodalton (kDa) region of Plasmodium yoelii merozoite surface protein 1 are induced by the C-terminal 19-kDa region but not the adjacent 33-kDa region. Infect. Immun. 70:820-825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anders, R. A., P. E. Crewther, S. Edwards, M. Margetts, M. L. S. M. Matthew, B. Pollock, and D. Pye. 1997. Immunization with recombinant AMA-1 protects mice against infection with Plasmodium chabaudi. Vaccine 16:240-247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Batchelder, J. M., J. M. Burns, Jr., F. K. Cigel, H. Lieberg, D. D. Manning, B. J. Pepper, D. M. Yanez, H. van der Heyde, and W. P. Weidanz. 2003. Plasmodium chabaudi: IFN-γ but not IL-2 is essential for the expression of cell-mediated immunity against blood-stage parasites in mice. Exp. Parasitol. 105:159-166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bouharoun-Tayoun, H., and P. Druilhe. 1992. Plasmodium falciparum malaria: evidence for an isotype imbalance which may be responsible for delayed acquisition of protective immunity. Infect. Immun. 60:1473-1481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bouharoun-Tayoun, H., C. Oeuvray, F. Lunel, and P. Druilhe. 1995. Mechanism underlying the monocyte-mediated antibody-dependent killing of Plasmodium falciparum asexual blood stages. J. Exp. Med. 182:409-418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Breman, J. G. 1999. The ears of the hippopotamus: manifestations, determinants and estimates of the malaria burden. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 64S:1-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burns, J. M., Jr., P. R. Flaherty, M. M. Romero, and W. P. Weidanz. 2003. Immunization against Plasmodium chabaudi malaria using combined formulations of apical membrane antigen-1 and merozoite surface protein-1. Vaccine 21:1843-1852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carlton, J. M., S. V. Angiuoli, B. B. Suh, T. W. Kooij, M. Pertea, J. C. Silva, M. D. Ermolaeva, J. E. Allen, J. D. Selengut, H. L. Koo, J. D. Peterson, M. Pop, D. S. Kosack, M. F. Shumway, S. L. Bidwell, S. J. Shallom, S. E. van Aken, S. B. Riedmuller, T. V. Feldblyum, J. K. Cho, J. Quackenbush, M. Sedegah, A. Shoaibi, L. M. Cummings, L. Florens, J. R. Yates, J. D. Raine, R. E. Sinden, M. A. Harris, D. A. Cunningham, P. R. Preiser, L. W. Bergman, A. B. Vaidya, L. H. van Lin, C. J. Janse, A. P. Waters, H. O. Smith, O. R. White, S. L. Salzberg, J. C. Venter, C. M. Fraser, S. L. Hoffman, M. J. Gardner, and D. J. Carucci. 2002. Genome sequence and comparative analysis of the model rodent malaria parasite Plasmodium yoelii yoelii. Nature 419:512-519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen, J., M. Trounstine, F. W. Alt, F. Young, C. Kurahara, J. F. Loring, and D. Huszar. 1993. Immunoglobulin gene rearrangement in B cell deficient mice generated by targeted deletion of the JH locus. Int. Immunol. 5:647-656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clark, I. A., and W. B. Cowden. 2003. The pathophysiology of falciparum malaria. Pharmacol. Ther. 99:221-260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crewther, P. E., M. L. S. M. Matthew, R. H. Flegg, and R. Anders. 1996. Protective immune responses to apical membrane antigen 1 of Plasmodium chabaudi involve recognition of strain-specific epitopes. Infect. Immun. 64:3310-3317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dalton, D. K., S. Pitts-Meek, S. Keshav, I. S. Figari, A. Bradley, and T. A. Stewart. 1993. Multiple defects of immune cell function in mice with disrupted interferon-γ genes. Science 259:1739-1742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Daly, T. M., and C. A. Long. 1995. Humoral response to a carboxyl-terminal region of the merozoite surface protein-1 plays a predominant role in controlling blood-stage infection in rodent malaria. J. Immunol. 155:236-243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Daly, T. M., and C. A. Long. 1996. Influence of adjuvant on protection induced by a recombinant fusion protein against malaria infection. Infect. Immun. 64:2602-2608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deleersnijder, W., D. Hendrix, N. Bendahman, J. Hanegreefs, L. Brijs, C. Hamers-Casterman, and R. Hamers. 1990. Molecular cloning and sequence analysis of the gene encoding the major merozoite surface antigen of Plasmodium chabaudi chabaudi IP-PC1. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 43:231-244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Egan, A., M. Waterfall, M. Pinder, A. Holder, and E. Riley. 1997. Characterization of human T- and B-cell epitopes in the C terminus of Plasmodium falciparum merozoite surface protein 1: evidence for poor T-cell recognition of polypeptides with numerous disulfide bonds. Infect. Immun. 65:3024-3031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Egan, A. F., J. A. Chappel, P. A. Burghaus, J. Morris, J. A. McBride, A. A. Holder, D. C. Kaslow, and E. M. Riley. 1995. Serum antibodies from malaria-exposed people recognize conserved epitopes formed by the two epidermal growth factor motifs of MSP119, the carboxy-terminal fragment of the major merozoite surface protein of Plasmodium falciparum. Infect. Immun. 63:456-466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gardner, M. J., N. Hall, E. Fung, O. White, M. Berriman, R. W. Hyman, J. M. Carlton, A. Pain, K. E. Nelson, S. Bowman, I. T. Paulsen, K. James, J. A. Eisen, K. Rutherford, S. L. Salzberg, A. Craig, S. Kyes, M. S. Chan, V. Nene, S. J. Shallom, B. Suh, J. Peterson, S. Angiuoli, M. Pertea, J. Allen, J. Selengut, D. Haft, M. W. Mather, A. B. Vaidya, D. M. Martin, A. H. Fairlamb, M. J. Fraunholz, D. S. Roos, S. A. Ralph, G. I. McFadden, L. M. Cummings, G. M. Subramanian, C. Mungall, J. C. Venter, D. J. Carucci, S. L. Hoffman, C. Newbold, R. W. Davis, C. M. Fraser, and B. Barrell. 2002. Genome sequence of the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Nature 419:498-511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Greenwood, B., and P. Alonso. 2002. Malaria vaccine trials. Chem. Immunol. 80:366-395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Groux, H., and J. Gysin. 1990. Opsonization as an effector mechanism in human protection against asexual blood stages of Plasmodium falciparum: functional role of IgG subclass. Res. Immunol. 141:529-542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grun, J. L., and W. P. Weidanz. 1981. Immunity to Plasmodium chabaudi adami in the B-cell deficient mouse. Nature 290:143-145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hirunpetcharat, C., J. H. Tian, D. C. Kaslow, N. van Rooijen, S. Kumar, J. A. Berzofsky, L. H. Miller, and M. F. Good. 1997. Complete protective immunity induced in mice by immunization with the 19-kilodalton carboxyl-terminal fragment of the merozoite surface protein-1 (MSP119) of Plasmodium yoelii expressed in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: correlation of protection with antigen-specific antibody titer, but not with effector CD4+ T cells. J. Immunol. 159:3400-3411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hirunpetcharat, C., P. Vukovic, X. Q. Liu, D. C. Kaslow, L. H. Miller, and M. F. Good. 1999. Absolute requirement for an active immune response involving B cells and Th cells in immunity to Plasmodium yoelii passively acquired with antibodies to the 19-kDa carboxyl-terminal fragment of merozoite surface protein-1. J. Immunol. 162:7309-7314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hodder, A. N., P. E. Crewther, and R. A. Anders. 2001. Specificity of the protective antibody response to apical membrane antigen 1. Infect. Immun. 69:3286-3294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hohara, S., P. Mombaerts, J. Lafaille, J. Iacomini, A. Nelson, A. R. Clark, M. L. Hooper, A. Farr, and S. Tonegawa. 1993. T cell receptor mutant mice: independent generation of αβ T cells and programmed rearrangement of γδ TCR genes. Cell 72:337-348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Holder, A. A. 1996. Preventing merozoite invasion of erythrocytes, p. 77-104. In S. L. Hoffman (ed.), Malaria vaccine development: a multi-immune response approach. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 27.Hollingdale, M. R., and U. Krzych. 2002. Immune responses to liver-stage parasites: implications for vaccine development. Chem. Immunol. 80:97-124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kuhn, R., K. Rajewsky, and W. Muller. 1991. Generation and analysis of interleukin-4 deficient mice. Science 254:707-710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kumar, S., J. E. Epstein, and T. L. Richie. 2002. Vaccine against asexual stage malaria parasites. Chem. Immunol. 80:262-286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kumar, S., A. Yadava, D. B. Keister, J. H. Tian, M. Ohl, K. A. Perdue-Greenfield, L. H. Miller, and D. C. Kaslow. 1995. Immunogenicity and in vivo efficacy of recombinant Plasmodium falciparum merozoite surface protein-1 in Aotus monkeys. Mol. Med. 1:325-332. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Langhorne, J., S. Gillard, B. Simon, S. Slade, and K. Eichman. 1989. Frequencies of CD4+ T cells reactive with Plasmodium chabaudi chabaudi: distinct response kinetics for cells with Th1 and Th2 characteristics during infection. Int. Immunol. 1:416-424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marshall, V. M., M. G. Peterson, A. M. Lew, and D. J. Kemp. 1989. Structure of the apical membrane antigen I (AMA-1) of Plasmodium chabaudi. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 37:281-284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Martin, R. M., J. L. Brady, and A. M. Lew. 1998. The need for IgG2c specific antiserum when isotyping antibodies from C57BL/6 and NOD mice. J. Immunol. Methods 212:187-192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McKean, P. G., K. O'Dea, and K. N. Brown. 1993. Nucleotide sequence analysis and epitope mapping of the merozoite surface protein 1 from Plasmodium chabaudi chabaudi AS. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 62:199-210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mohan, K., and M. M. Stevenson. 1998. Acquired immunity to asexual blood stages, p. 467-493. In I. W. Sherman (ed.), Malaria: parasite biology, pathogenesis, and protection. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 36.Perlmann, P., and M. Troye-Blomberg. 2002. Malaria and the immune system in humans. Chem. Immunol. 80:229-242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Richie, T. L., and A. Saul. 2002. Progress and challenges for malaria vaccines. Nature 415:694-701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rotman, H. L., T. M. Daly, R. Clynes, and C. A. Long. 1998. Fc receptors are not required for antibody-mediated protection against lethal malaria challenge in a mouse model. J. Immunol. 161:1908-1912. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rotman, H. L., T. M. Daly, and C. A. Long. 1999. Plasmodium: immunization with the carboxyl-terminal regions of MSP-1 protects against homologous but not heterologous blood-stage parasite challenge. Exp. Parasitol. 91:78-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stevenson, M. M., and E. Riley. 2004. Innate immunity to malaria. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 4:169-180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stevenson, M. M., and M. F. Tam. 1993. Differential induction of helper T cell subsets during blood-stage Plasmodium chabaudi (AS) infection in resistant and susceptible mice. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 92:77-83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Su, Z., and M. M. Stevenson. 2000. Central role of endogenous gamma interferon in protective immunity against blood-stage Plasmodium chabaudi AS infection. Infect. Immun. 68:4399-4406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Su, Z., and M. M. Stevenson. 2002. IL-12 is required for antibody-mediated protective immunity against blood-stage Plasmodium chabaudi AS malaria infection in mice. J. Immunol. 168:1348-1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Su, Z., M. Tam, D. Jankovic, and M. M. Stevenson. 2003. Vaccination with novel immunostimulatory adjuvants against blood-stage malaria in mice. Infect. Immun. 71:5178-5187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Udhayakumar, V., D. Anyona, S. Kariuki, Y. P. Shi, P. B. Bloland, O. H. Branch, W. Weiss, B. L. Nahlen, D. C. Kaslow, and A. A. Lal. 1995. Identification of T and B cell epitopes recognized by humans in the C-terminal 42-kDa domain of the Plasmodium falciparum merozoite surface protein (MSP)-1. J. Immunol. 154:6022-6030. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.van der Heyde, H. C., W.-L. Chang, and W. P. Weidanz. 1997. Specific immunity to malaria and the pathogenesis of disease, p. 195-226. In S. H. E. Kaufmann (ed.), Host response to intracellular pathogens. R. G. Landes Company Biomedical Publishers, Austin, Tex.

- 47.van der Heyde, H. C., M. M. Elloso, W.-L. Chang, M. Kaplan, D. D. Manning, and W. P. Weidanz. 1995. γδ T cells function in cell-mediated immunity to acute blood-stage Plasmodium chabaudi adami malaria. J. Immunol. 154:3985-3990. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.van der Heyde, H. C., D. Huszar, C. Woodhouse, D. D. Manning, and W. P. Weidanz. 1994. The resolution of acute malaria in a definitive model of B cell deficiency, the JHD mouse. J. Immunol. 152:4557-4562. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.van der Heyde, H. C., B. Pepper, J. Batchelder, F. Cigel, and W. P. Weidanz. 1997. The time course of selected malarial infections in cytokine-deficient mice. Exp. Parasitol. 85:206-213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.von der Weid, T., N. Honarvar, and J. Langhorne. 1996. Gene-targeted mice lacking B cells are unable to eliminate a blood stage malaria infection. J. Immunol. 156:2510-2516. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vukovic, P., P. M. Hogarth, N. Barnes, D. C. Kaslow, and M. G. Good. 2000. Immunoglobulin G3 antibodies specific for the 19-kilodalton carboxyl-terminal fragment of Plasmodium yoelii merozoite surface protein 1 transfer protection to mice deficient in Fc-γRI receptors. Infect. Immun. 68:3019-3022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Weidanz, W. P., J. R. Kemp, J. M. Batchelder, F. K. Cigel, M. Sandor, and H. C. van der Heyde. 1999. Plasticity of immune response suppressing parasitemia during acute Plasmodium chabaudi malaria. J. Immunol. 162:7383-7388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.White, W. I., C. B. Evans, and D. W. Taylor. 1991. Antimalarial antibodies of the immunoglobulin G2a isotype modulate parasitemias in mice infected with Plasmodium yoelii. Infect. Immun. 59:3547-3554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wipasa, J., C. Hirunpetcharat, Y. Mahakunkijcharoen, H. Xu, S. Elliott, and M. F. Good. 2002. Identification of T cell epitopes on the 33-kDa fragment of Plasmodium yoelii merozoite surface protein 1 and their antibody-independent protective role in immunity to blood stage malaria. J. Immunol. 169:944-951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Xu, H., A. N. Hodder, H. Yan, P. E. Crewther, R. A. Anders, and M. J. Good. 2000. CD4+ T cells acting independently of antibody contribute to protective immunity to Plasmodium chabaudi infection after apical membrane antigen 1 immunization. J. Immunol. 165:389-396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]