Abstract

This study evaluated the effect of a 12-week social marketing intervention conducted in 2012 promoting 1% milk use relying on paid advertising. Weekly milk sales data by type of milk (whole, 2%, 1%, and nonfat milk) were collected from 80 supermarkets in the Oklahoma City media market, the intervention market, and 66 supermarkets in the Tulsa media market (TMM), the comparison market. The effect was measured with a paired t-test. A mixed segmented regression model, controlling for the contextual difference between supermarkets and data correlation, identified trends before, during, and after the intervention. Results show the monthly market share of 1% milk sales changed from 10.0% to 11.5%, a 15% increase. Evaluating the volume sold, the monthly mean number of gallons of 1% milk sold increased from 890.5 gal (SD = 769.8) per supermarket from before the intervention to 1070.7 gal (SD = 922.5) following the intervention (t(79) = 9.4, p = 0.000). Moreover, average weekly sales of 1% milk were stable prior to the intervention (b = − 0.2 gal/week, 95% CI [− 0.6 gal/week, 0.3 gal/week]). During each additional week of the intervention, 1% milk sales increased by an average of 4.1 gal in all supermarkets (95% CI [3.5 gal/week, 4.6 gal/week]). Three months later, albeit attenuated, a significant increase in 1% milk sales remained. In the comparison market, no change in the market share of 1% milk occurred. Paid advertising, using the principles of social marketing, can be effective in changing an entrenched and habitual nutrition habit.

Keywords: Social marketing, Milk, Segmented regression, Mass communication, Paid advertising, Program evaluation

Highlights

-

•

Most Americans consume high-fat milk, a pattern the Dietary Guidelines for Americans seeks to change.

-

•

An intervention, applying social marketing, led to a significant increase in 1% milk sales.

-

•

Promotion was based on paid advertising alone, without community activities or public relations.

-

•

This change occurred in a geographically dispersed area and among a large, diverse population.

-

•

A segmented regression model is an effective means of evaluating changes in nutrition behavior.

1. Introduction

Most Americans consume high-fat milk, a preference the Dietary Guidelines for Americans has sought to change (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and U.S. Depart, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and U.S. Depart). The 2003–2004 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey documented that 74% of all milk consumed was either whole (32.3%) or 2% milk (41.7%) while 1% and nonfat milk together represented just 26% of milk consumed (10.4% and 15.6% respectively) (Britten et al., 2007). National milk sales data corroborates these findings. In 2003–2004, 71.4% of milk sales were high-fat milk products—36% were sales of whole milk and 35.5% were 2% milk sales. Low-fat milk sales represented 28.6% of all milk sales—12.7% were 1% milk sales and an additional 15.9% were nonfat milk sales (U.S. Department of Agriculture, 2012). The purpose of this research was to test the effectiveness of a social marketing intervention promoting the use of 1% milk, 1% Low-Fat Milk Has Perks!.

Previous interventions promoting the consumption of low-fat milk have reported mixed results. Of these, the 1% or Less campaign is the most studied intervention. Initially, this intervention promoting low-fat milk was implemented in several small, sociodemographically homogenous cities (< 35,000 population) in West Virginia, with each campaign testing the effectiveness of a different promotional strategy (Booth-Butterfield and Reger, 2004, Reger et al., 1998, Reger et al., 1999, Reger et al., 2000, Wootan et al., 2005). The 1% or Less intervention was based on the theory of reasoned action that posits behavior is best predicted by intention, which is determined by attitude and subjective normative beliefs. The intervention promoted the health benefits, price savings, and taste of low-fat milk (Booth-Butterfield and Reger, 2004). Its effect was measured, in part, by the change in mean monthly low-fat milk sales per supermarket from immediately before to immediately following the intervention.

These studies concluded that a combination of paid advertising, public relations, and community-based outreach was most effective in increasing low-fat milk sales (Reger et al., 1998, Wootan et al., 2005). However, the intervention did not produce a significant effect when implemented using paid advertising alone or a combination of community events with public relations (Reger et al., 2000, Wootan et al., 2005). Subsequently, the 1% or Less campaign was replicated in a primarily Hispanic community in California and the state of Hawaii (Hinkle et al., 2008, Maddock et al., 2007). In both instances, the intervention strategy included community-based events, paid advertising, and print media. In California, the increase in low-fat milk sales was more modest following the 1% or Less intervention than the similar West Virginia intervention, and the effect was not sustained (Hinkle et al., 2008, Reger et al., 1998).

Results of the 1% or Less intervention were also mixed when replicated in Hawaii, which, compared to West Virginia, is a large media market with a multi-ethnic population (Maddock et al., 2007). In that intervention, pre-and post-intervention telephone surveys revealed a significant increase in low-fat milk use immediately after the intervention and a modest overall increase three months later. The significant increase in self-reported low-fat milk immediately after the intervention was confined to Whites and Filipinos, and three months later no significant effect by ethnicity was identified. Notably, the failure to identify an effect by ethnicity may have been attributable to small sample sizes.

When taken together, the 1% or Less studies conducted in Hawaii and California raise questions of the generalizability of this intervention. Moreover, the West Virginia studies raise the question whether paid advertising alone can produce a significant change in a nutrition behavior.

The 1% Low-Fat Milk Has Perks! social marketing intervention sought to address these issues. This intervention used paid advertising only to promote 1% milk and was implemented in a large but diverse media market.

Formative research based on seven focus group discussions, and using mixed methods, was conducted in Oklahoma City. That research revealed poor milk nutrition knowledge and myths influenced the type of milk usually chosen. Based on this research, the 1% Low-Fat Milk Has Perks! intervention promoted the following four key messages: 1) 2% is not low-fat milk; 2) 1% low-fat milk is not watered down; 3) 1% low-fat milk has the same nutrients as 2% milk and whole milk; 4) 1% low-fat milk has the same Vitamin D as 2% milk and whole milk. The formative research also revealed that 2% milk consumers were more willing to consider using 1% milk than whole milk consumers. Therefore, we hypothesized that sales of 2% milk would decrease more than sales of whole milk, and that the reduction would be reflected in an increase in the targeted behavior, sales of 1% milk.

1. Methods

1.1. Design

1.1.1. Intervention and comparison area

The Oklahoma City (OKCMM) and Tulsa (TMM) media markets, the two largest media markets in Oklahoma, were chosen as the intervention and comparison areas, respectively. As the study's comparison area, the TMM received no media exposure or other intervention components. As seen in Table 1 the sociodemographic characteristics of the two media markets are very similar (U.S. Census Bureau, 2016).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the Oklahoma City and Tulsa media markets (2008 - 2012 American Community Survey).

| OKCMM | TMM | |

|---|---|---|

| Total population | 1,809,404 | 1,303,368 |

| Characteristic | % | % |

| Ethnicity | ||

| White | 70.3 | 67.1 |

| Black | 7.8 | 6.8 |

| American Indian | 4.5 | 8.9 |

| Hispanic | 10.0 | 7.1 |

| Asian | 2.3 | 1.5 |

| Other and mixed race | 5.1 | 8.5 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 49.6 | 49.2 |

| Female | 50.4 | 50.8 |

| Educational attainment | ||

| Not a high school graduate | 13.3 | 13.0 |

| High school graduate | 30.1 | 31.6 |

| Some college | 31.2 | 32.1 |

| College graduate | 25.4 | 23.4 |

| Marital status (15 and over) | ||

| Not married | 49.2 | 47.2 |

| Married | 50.8 | 52.8 |

| Geographic location | ||

| Urban county | 54.0 | 46.2 |

| Rural county | 35.3 | 42.8 |

| Mixed county | 10.7 | 11.0 |

| Size of household | ||

| 1 person | 28.2 | 28.0 |

| 2 people | 34.8 | 35.5 |

| 3 people or more | 36.9 | 36.5 |

| Percent of population living near poverty | ||

| < 100% of FPL | 16.1 | 16.0 |

| 100% to 199% of FPL | 21.0 | 21.3 |

| 200% of FPL and over | 62.9 | 62.7 |

1.1.2. Intervention

The 12-week 1% Low-Fat Milk Has Perks! intervention ran from June 11, 2012 to September 2, 2012, relying on television and radio commercials, print advertisements, billboards and bus wraps, point-of-sale promotional items, and digital media. Kendrick Perkins, a professional basketball player with the Oklahoma City NBA franchise, was the celebrity spokesperson.

1.1.2.1. Television and radio advertising

Four 30-second television commercials and two 30-second radio commercials ran during the intervention. The television commercials ran 1117 times in English (an average of 14.3 spots per day), and 154 spots were broadcast in Spanish (an average of 1.9 per day). It is estimated that 99% of adults in the English viewing audience (age 18 and older) viewed the television commercials, on average, 24.2 times, and that 23.1% of the Spanish speaking population was reached, and viewed the commercials an average of 4.2 times. Two English radio commercials (454 spots) were broadcast for an average of 5.5 spots per day. On the Spanish radio station, 295 spots aired, an average of 3.6 spots per day. Approximately 37.9% and 18.5% of English and Spanish speaking adults were reached respectively through radio.

1.1.2.2. Billboards and bus wraps

Billboards were placed in the Oklahoma City metropolitan area, including three digital billboards plus 73 print billboards donated by a collaborating local supermarket. Advertisements were also displayed on exteriors of six busses and in the interiors of 65 busses that circulated in the Oklahoma City transit system.

1.1.2.3. Print media

Twelve print advertisements ran in free community newspapers and magazines that are widely distributed in the metropolitan area.

1.1.2.4. Point-of-sale promotional items

Promotional and point-of-sale items included life-size cutouts of Perkins, dairy case clings, souvenir buttons, and a handout with nutrition information entitled ‘Lactoid Factoids.’ In the metropolitan area, these point-of sale items were prominently displayed near dairy cases in 36 supermarkets and placed in seven Oklahoma Department of Human Service centers, two county health department offices, and one local public library. To ensure program fidelity, project staff monitored the availability and placement of point-of-sale items weekly.

1.1.2.5. Digital media

Digital media included Pandora, a website, and YouTube. Pandora had 3.35 million impressions, generating 23,963 clicks on the commercials. The interactive website, available in English and Spanish, reinforced the theme of the intervention. From the website home page, 8,296 unique visitors clicked on an icon and received milk nutrition messages. YouTube videos, the 30-second commercials created for television, were viewed 53,000 times.

1.1.3. Supermarket milk sales data

Five grocery chains, representing 146 supermarkets, provided milk sales data, including 80 stores in the OKCMM and 66 stores in the TMM. We calculated each store's total weekly number of gallons sold for whole, 2%, 1%, and nonfat milk. Sales data for buttermilk, flavored, and lactose-free milk products were not requested, nor was data on milk containers smaller than a half-gallon.

To allow comparability of the results of the 1% Low-Fat Milk Has Perks! intervention to previous studies, a summary by type (whole, 2%, 1%, and nonfat milk) of the total number of gallons sold, the proportion of milk sales (market share), and the mean number of gallons sold per supermarket were calculated for monthly periods. Paired t-tests assessed differences in the monthly mean number of gallons of 1% milk sold per supermarket from prior to the intervention to after it ended for both media markets, as well as two and three months after the intervention ended. The effect size r was calculated for the change in 1% milk sales.

The main analysis is a mixed segmented regression model that evaluated the impact of the 1% Low-Fat Milk Has Perks! intervention. We defined the three segments based on weekly time periods; baseline period (March 4 – June 2, 2012), intervention period (June 3 – September 1, 2012), and post-intervention period (September 2, 2012 to the end of December 2012). The segmented regression analysis examined milk sales by type (whole, 2%, 1%, and nonfat milk) in the two media markets. Store-specific intercepts and slopes accounted for non-independence of a given store's weekly sales reports and incorporated an unstructured covariance matrix (Durban-Watson test statistic = 0.57). A repeated-measure ANOVA identified the level of week-to-week changes in 1% milk sales. All data were analyzed using SPSS Version 20.0. The threshold for determining statistical significance was a two-tailed test with 0.05 as the alpha level.

2. Results

2.1. Pre- and post-intervention changes in the mean gallons of 1% milk sold

Table 2 summarizes the sales of each type of milk during the study in the OKCMM. As seen in Table 2, the market share of 1% milk sold increased from 10.0% in April to 11.5% in September, a 15% increase. The data demonstrates that the total number of gallons of 1% milk sold increased from 71,239 gal prior to the intervention, (April, 2012), to 85,659 gal the month immediately after the intervention (September 2012). In other words, for this time-period, the monthly mean number of gallons of 1% milk sold per supermarket increased from 890.5 gal (SD = 769.8) to 1070.7 gal (SD = 922.5) resulting in a mean difference of 180.2 gal per supermarket (95% CI [142.1 gal/mo., 218.4 gal/mo.], t(79) = 9.4, p = 0.000, effect size r = 0.73).

Table 2.

Gallons of milk sold during four key months in the Oklahoma City media market.

| OKCMM | April 2012 (Baseline) |

September 2012 (Post-intervention) |

November 2012 (Two-month follow-up) |

December 2012 (Three-month follow-up) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | M | %a | Total | M | %a | Total | M | %a | Total | M | %a | |

| Nonfat milk | 72,080 | 889.9 | 10.1 | 74,311 | 917.4 | 9.9 | 69,708 | 860.6 | 9.6 | 68,794 | 849.3 | 9.0 |

| 1% milk | 71,239 | 890.5 | 10.0 | 85,659 | 1070.7 | 11.5 | 77,962 | 974.5 | 10.7 | 78,497 | 981.2 | 10.3 |

| 2% milk | 306,469 | 3783.6 | 42.8 | 323,461 | 3993.3 | 43.3 | 314,582 | 3883.7 | 43.4 | 331,998 | 4098.7 | 43.5 |

| Whole milk | 265,664 | 3279.8 | 37.1 | 264,360 | 3263.7 | 35.4 | 263,093 | 3248.1 | 36.3 | 283,814 | 3503.9 | 37.2 |

| Total | 715,451 | 2215.0 | 100.0 | 747,790 | 2315.1 | 100.0 | 725,345 | 2245.7 | 100.0 | 763,102 | 2362.5 | 100.0 |

Proportion of the market share of gallons of milk sold by type.

Although sales of 1% milk declined after the intervention ended, two months later (November 2012), the average gallons of 1% milk sold per supermarket was still 9.4% higher than before the intervention (t(79) = 5.8, p = 0.00, effect r = 0.54). Moreover, 1% milk sales remained 3.0% higher three months after the intervention ended than before it was initiated in April, evidence of a sustained effect (t(79) = 5.2, p = 0.00, effect r = 0.50).

The total volume of 1% milk sold also increased in the TMM during the same time-period as the intervention in the OKCMM (Table 3). The monthly mean number of gallons of 1% milk sold per supermarket increased 4.8%, from 826.2 gal (SD = 700.7) to 865.8 (SD = 701.0, or an average change of 39.6 gal/mo (95% CI: 14.2 gal/mo., 64.9 gal/mo.). This was a significant increase in monthly 1% milk sales, (t(65) = 3.1, p = 0.000, effect r = 0.36). However, comparing the independent effect sizes, the monthly mean number of gallons of 1% milk sold per supermarket improved significantly more in the OKCMM than in the TMM, p (two-tailed) < 0.001.

Table 3.

Gallons of milk sold during four key months in the Tulsa media market.

| TMM | April 2012 (Baseline) |

September 2012 (Post-intervention) |

November 2012 (Two-month follow-up) |

December 2012 (Three-month follow-up) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | M | %a | Total | M | %a | Total | M | %a | Total | M | %a | |

| Nonfat milk | 71,980 | 1090.6 | 11.3 | 77,340 | 1171.8 | 11.4 | 72,451 | 1097.7 | 10.8 | 71,801 | 1087.9 | 10.3 |

| 1% milk | 54,530 | 826.2 | 8.5 | 57,143 | 865.8 | 8.4 | 53,901 | 816.7 | 8.0 | 54,077 | 819.3 | 7.7 |

| 2% milk | 295,948 | 4484.1 | 46.3 | 311,535 | 4720.2 | 46.0 | 309,163 | 4684.3 | 46.0 | 322,696 | 4889.3 | 46.2 |

| Whole milk | 216,685 | 3283.1 | 33.9 | 231,457 | 3506.9 | 34.2 | 237,297 | 3595.4 | 35.3 | 250,030 | 3788.3 | 35.8 |

| Total | 639,142 | 2421.0 | 100.0 | 677,474 | 2566.2 | 100.0 | 672,811 | 2548.5 | 100.0 | 698,603 | 2646.2 | 100.0 |

Proportion of the market share of gallons of milk sold by type.

Moreover, even though the number of gallons of 1% milk sold increased in the TMM, there was no change in the market share of 1% milk, and increases in the monthly mean number of gallons of milk sold in the TMM occurred across all types of milk (Table 3).

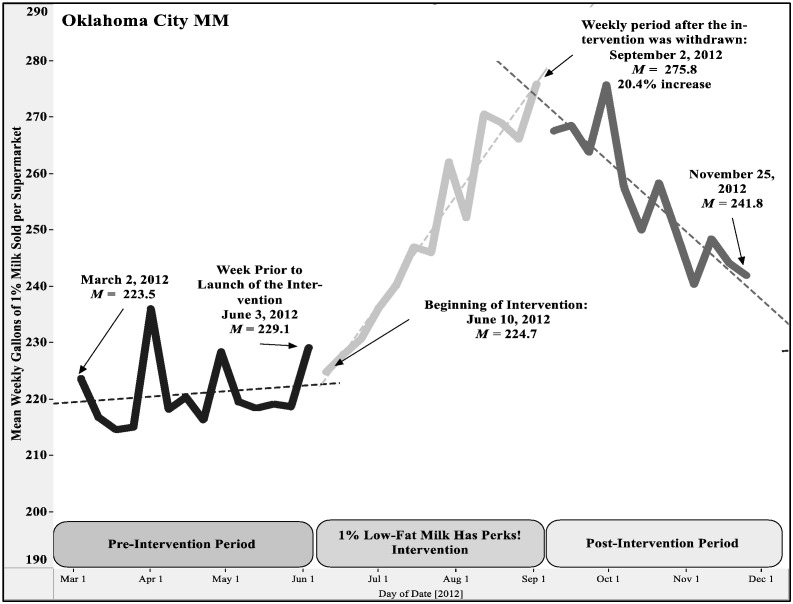

2.2. Changes in the weekly trends in 1% milk sales (Oklahoma City media market)

Fig. 1 segments weekly observations of the average number of gallons of 1% milk sold per supermarket into three time-periods: the 12-week period before the intervention (Pre-Intervention Period); the time of the intervention (1% Low-Fat Milk Has Perks! intervention); and 12 weeks after the intervention ended (Post-Intervention). This figure reveals little week to week change in the mean number of gallons of 1% milk sold prior to the intervention. Yet, the average number of gallons of 1% milk sold steadily increased each week after the intervention was implemented.

Fig. 1.

1% milk sales, weekly mean gallons sold per supermarket in the OKCMM (segmented by 12-week periods).

The segmented regression model measured the magnitude of these changes (Table 4). As illustrated by Fig. 1, average weekly sales of 1% milk varied little before the intervention (b = − 0.2 gal/week, 95% CI [− 0.6 gal/week, 0.3 gal/week]; Table 4). During the intervention, 1% milk sales increased by an average of 4.1 gal per week per store (95% CI [3.5 gal/week, 4.6 gal/week]; Table 4). During the 3-month period after the intervention ended, weekly 1% milk sales trended downward (b = − 6.7 gal/week, 95% CI [− 7.3 gal/week, − 6.3 gal/week]; Table 4).

Table 4.

Change in weekly trend of 1% milk sales, gallons per supermarket (OKCMM).

| Oklahoma City MM | Coefficient | Standard error | 95% CI | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean gallons of 1% milk sold at baseline, March 4–10 (intercept) | 221.088 | 20.551 | 180.194 | 261.981 | 0.000 |

| Weekly trend prior to intervention, March 11–June 2 (slope) | − 0.149 | 0.219 | − 0.579 | 0.281 | 0.495 |

| Change in trend during the intervention, June 10–September 1 (slope) | 4.057 | 0.281 | 3.505 | 4.608 | 0.000 |

| Change in mean gallons of 1% milk sold the week the intervention ended (September 2–8) | 7.179 | 2.054 | 3.152 | 11.205 | 0.000 |

| Change in trend three months after intervention (September 9–December 1) | − 6.784 | 0.250 | − 7.273 | − 6.295 | 0.000 |

Note. The level intercept or mean number of gallons of 1% milk (level) sold the week before the intervention (June 3–9) did not significantly change. Therefore, this parameter estimate does not change the trend of 1% milk sales during the intervention, nor does it add to interpretation of the findings from this regression model. Thus, the variable was removed from the model.

The repeated-measures ANOVA revealed that 1% milk sales began increasing during the third week of the intervention and continued to increase until the eleventh week. By the sixth-week of the 1% Low-Fat Milk Has Perks! intervention, or the intervention midpoint, the mean gallons of 1% milk sold per supermarket was significantly higher than the week prior to beginning of the intervention, p = 0.00.

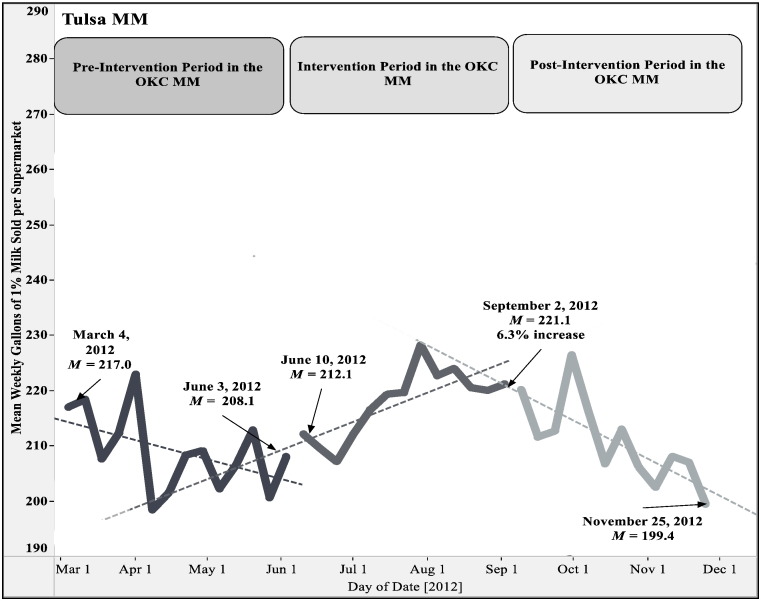

2.3. Change in the weekly trend of 1% milk sales (Tulsa media market)

In the TMM, during the 12-week period prior to the intervention in the OKCMM, 1% milk sales declined slightly, (Fig. 2 and Table 5). Fig. 2 also illustrates that weekly 1% milk sales began to increase modestly in the TMM during the intervention period, and then declined steeply during the post-intervention period.

Fig. 2.

1% milk sales, weekly mean gallons sold per supermarket in the TMM (segmented).

Table 5.

Change in weekly trend of 1% milk sales, gallons per supermarket (TMM).

| Tulsa MM | Coefficient | Standard error | 95% CI | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean gallons of 1% milk sold at baseline, March 4–10 (Intercept) | 215.926 | 21.776 | 172.454 | 259.398 | 0.000 |

| Weekly trend prior to intervention, March 11–June 2 (slope) | − 0.978 | 0.217 | − 1.403 | − 0.552 | 0.000 |

| Change in mean gallons of 1% milk sold the week prior to the intervention, June 3–9, (intercept) | 3.958 | 2.024 | − 0.011 | 7.927 | 0.051 |

| Change in trend during the intervention, June 10–September 1 (slope) | 2.372 | 0.269 | 1.844 | 2.900 | 0.000 |

| Change in mean gallons of 1% milk sold the week the intervention ended (September 2–8) | − 2.698 | 2.024 | − 6.667 | 1.271 | 0.183 |

| Change in trend three months after intervention (September 9–December 1) | − 2.960 | 0.269 | − 3.488 | − 2.432 | 0.000 |

In the TMM, the segmented regression analysis revealed that the positive trend in weekly 1% milk sales was a significant change (Table 5). However, the evidence revealed the rate of change averaged 2.4 gal each week per supermarket (Table 5), a rate much smaller than the 4.1 gal average weekly increase in 1% milk sales in each supermarket located in the OKCMM (Table 4).

2.4. Nonfat milk sales (Oklahoma City media market)

The evidence revealed no change in the market share of nonfat milk sales in the OKCMM (Table 2), ruling out that the increase in 1% milk sales was attributable to an undesirable and unintended consequence of consumers purchasing it instead of nonfat milk.

2.5. High-fat milk sales

2.5.1. Changes in whole milk sales

Whole milk purchases declined in the OKCMM. The monthly market share of whole milk decreased from 37.1% in April to 35.4% in September, a 4.6% relative decrease (Table 2). In comparison, for the same-time period, the monthly market share of whole milk remained about the same in the TMM, a 0.9% increase (Table 3).

In addition, the segmented regression analysis (results not shown) revealed that the change in the weekly trend of whole milk sales neither rose nor fell significantly in the OKCMM, p = 0.80 (b = − 0.3, 95% CI [− 0.2.2 gal/week, 1.7 gal/week]). The quantity of whole milk sold rose in the TMM (p = 0.00, b = 9.3, 95% CI [6.6 gal/week, 11.9 gal/week]).

2.5.2. Changes in 2% milk sales

The market share of 2% milk, increased from 42.8% in April to 43.3% in September, the month immediately after the intervention ended in the OKCMM, a non-significant 1.2% increase (Table 2). There was also no change in the market share of 2% milk sales in the TMM Table 3). The monthly market share of 2% milk was 46.3% of all milk sales in April and remained at 46.0% in September (a 0.7% decrease).

3. Discussion

The 1% Low-Fat Milk Has Perks! intervention clearly resulted in a significant increase in 1% milk sales in the OKCMM from before the intervention to after it ended. The results are consistent across multiple measures. The monthly market share of 1% milk improved 15% from April to September. The week-to-week trend in the amount of 1% milk sold in the OKCMM significantly increased during the intervention. Moreover, no positive trend in weekly 1% milk sales existed prior to the intervention in the OKCMM, ruling out the possibility that the gain in 1% milk sales was attributable to a growing demand for 1% milk that existed prior to the intervention.

Although an increase in 1% milk sales was also observed in the TMM, the monthly mean number of gallons of 1% milk sold per supermarket improved significantly more in the OKCMM from before to immediately after the intervention ended. Moreover, the market share of 1% milk sold in the comparison TMM did not change during the period of the intervention, while a 15% increase occurred in the intervention media market. The data suggests that the increase in the number of units of 1% milk sold in the TMM was because of a general temporal increase in the demand for all types of milk, not campaign spillover.

As further evidence that the 1% Low-Fat Milk Has Perks! intervention was the reason for the increase in 1% milk sales in the OKCMM, the market share of nonfat milk did not change in the OKCMM during the intervention period. Hence the increase in 1% milk was not attributable to users of nonfat milk purchasing 1% milk. No factor other than the intervention explains the increase in 1% milk sales in the OKCMM.

One unexpected finding emerged. The formative research revealed that the type of milk chosen was a firmly entrenched habit but that 2% milk users were more willing to consider low-fat milk than whole milk users. Our hypothesis was that the largest reduction would be in the quantity of 2% milk sold. Yet, this study found that the market share of whole milk declined 4.6% from before to immediately after the intervention and the market share of 2% milk slightly increased (1.2%). This finding suggests that whole milk users made at least a “one-step” change to 2% milk. If so, this would explain why 2% milk sales increased slightly instead of decreasing as expected.

As expected, a portion of the intervention effect decayed after the intervention ended. Yet, a significant effect remained two and three months after the campaign ended, indicating a sustained intervention impact. Notably, the post-intervention period included November and December, when special holiday meals may have influenced milk purchases. Given that the market share of 1% milk declined slightly in Tulsa during this same time period, some portion of the loss of effect is likely attributable to an increased use of higher fat milk during the holiday season.

The impact of the 1% Low-Fat Milk Has Perks! intervention, effect r = 0.73, compares favorably with the most successful of the 1% or Less interventions (effect r = 0.63, N = 12) (Wootan et al., 2005). In fact, there is no significant difference in these effect sizes, p = 0.60, which has important implications. For one, a significant change in the targeted behavior in a larger media market means more lives were touched than in a smaller market.

To illustrate, in the 1% or Less intervention, the largest effect was realized in Clarksburg and Bridgeport, West Virginia (Reger et al., 1998, Wootan et al., 2005). These intervention cities had a combined population of 25,000, and given the population size, the 1% or Less intervention resulted in an estimated 5750 people changing from high to low-fat milk. In contrast, in this 1% Low-Fat Milk Has Perks! intervention, the media market contained 1.8 million people, and a 1.5% absolute increase in 1% milk use could signify that as many as 27,000 people adopted low-fat milk.

Another important aspect of the 1% Low-Fat Milk Has Perks! intervention was that it relied exclusively on paid advertising for promotion in a large, ethnically diverse population. In contrast, the 1% or Less intervention implemented in West Virginia was implemented among a relatively small, homogenous population, primarily white, and the intervention included paid advertising, public relations, and community-based activities (Reger et al., 1998). Community-based activities can be effective but are expensive to implement, thus making these activities impossible in a large, ethnically diverse, and geographically dispersed area. The success of the 1% Low-Fat Milk Has Perks! intervention reveals that paid advertising alone, based on the principles and techniques of social marketing, can be effective in changing an entrenched and habitual nutrition behavior in a geographically dispersed area and among a large, ethnically diverse population.

A methodological strength of this study is its quasi-experimental design and its use of a segmented regression mixed model to evaluate the temporal impact of the 1% Low-Fat Milk Has Perks! intervention. Wagner and colleagues maintain a segment regression model is the best statistical method to evaluate the effect in a quasi-experimental design (Wagner et al., 2002). It controls for pre-intervention trends, for correlation among individual stores' weekly sales figures, and for the contextual differences between stores. Graphing time-series data also provides a convincing visual representation of different trends.

4. Conclusion

1% Low-Fat Milk Has Perks!, a multi-level social marketing campaign, increased low-fat milk use at the population level and revealed that a rigorous social marketing campaign based on consumer psychographics can be an effective way to change an entrenched behavior through paid advertising alone. In addition, the quasi-experimental design and segmented regression analysis is an effective means of evaluating a change in nutrition behavior and provides insight into trends before, during, and after the intervention. Overall, this intervention increased the market share of 1% milk sales by 15%, and a significant effect was sustained three months after the intervention ended. Moreover, average weekly sales of 1% milk were stable prior to the intervention but increased by an average of 4.1 gal per supermarket for each additional week of the intervention.

Acknowledgments

Partial support for this project came from the U.S. Department of Agriculture through the Oklahoma Department of Human Services through the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, Nutrition Education Grant (Robert John, PI). The U.S. Department of Agriculture and the Oklahoma Department of Human Services had no role in the design, analysis, or writing of this article. The views expressed here are the authors and do not reflect the views of the funding agencies. This research was part of the program evaluation of a 1% low-fat milk intervention conducted by the Oklahoma Nutrition Information and Education Social Marketing Project that received the National Social Marketing Centre (Great Britain) Award for Excellence in Social Marketing announced at the University of South Florida's 24th Social Marketing Conference, 2016. In addition, we would like to thank Meredith S. Scott, Nicholas Sumpter, and Marcy Roberts for their contributions to this research project.

Contributor Information

Karla Jaye Finnell, Email: karla-finnell@ouhsc.edu.

Robert John, Email: robert-john@ouhsc.edu.

David M. Thompson, Email: dave-thompson@ouhsc.edu.

References

- Booth-Butterfield S., Reger B. The message changes belief and the rest is theory: the 1% or less milk campaign and reasoned action. Prev. Med. 2004;39(3):581–588. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britten P., Marcoe K., Juan W., Guenther P.M., Carlson A. Nutrition Insights. 2007. Trends in consumer food choices within the MyPyramid milk group; p. 35. (http://www.cnpp.usda.gov/Publications/NutritionInsights/Insight35.pdf. Accessed 14 May 2012) [Google Scholar]

- Hinkle A.J., Mistry R., McCarthy W.J., Yancey A.K. Adapting the 1% or less milk campaign for a Hispanic/Latino population: the adelante con leche semi- descremada 1% experience. Am. J. Health Promot. 2008;23(2):108–111. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.07080780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maddock J.E., Maglione C., Barnett J., Cabot C., Jackson S., Reger-Nash B. Statewide implementation of the 1% or less campaign. Health Educ. Behav. 2007;34:953–963. doi: 10.1177/1090198106290621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reger B., Wootan M.G., Booth-Butterfield S., Smith H. 1% or less: a community-based nutrition campaign. Public Health Rep. 1998;113:410–419. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reger B., Wootan M., Booth-Butterfield S. Using mass media to promote healthy eating: a community-based demonstration project. Prev. Med. 1999;29(5):414–421. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1998.0570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reger B., Wootan M., Booth-Butterfield S. A comparison of different approaches to promote community-wide dietary change. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2000;18(4):271–275. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(00)00118-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau . 2016. 2008–2012 American Community Survey. Multiple Summary Files. (Available from http://factfinder2.census.gov; 30 October) [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Agriculture Fluid milk sales by product (annual) [data file] 2012. http://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/dairy-data.aspx (Available from Economic Research Service) (Accessed 17 June 2014)

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and U.S. Department of Agriculture . 2010. Dietary Guidelines of Americans. (http://www.health.gov/dietaryguidelines/2010.asp. Accessed 20 November 2011.) [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and U.S. Department of Agriculture . 8th eds. 2015. 2015–2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans. (http://health.gov/dietaryguidelines/2015/guidelines/. Accessed 1 February 2016) [Google Scholar]

- Wagner A.K., Soumerai S.B., Zhang F., Ross-Degan D. Segmented regression analysis of interrupted time series studies in medication use research. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 2002;27:299–309. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2710.2002.00430.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wootan M.G., Reger-Nash B., Booth-Butterfield S., Cooper L. The cost- effectiveness of 1% or less media campaigns promoting low-fat milk consumption. Prev. Chronic Dis.: Public Health Res. Pract. Policy. 2005;2(4):1–10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]