Abstract

Setting: A mixed-methods operational research (OR) study was conducted to examine the diagnosis and treatment pathway of patients with presumptive multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) during 2012–2013 under the national TB programme in Puducherry, India. High pre-diagnosis and pre-treatment attrition and the reasons for these were identified. The recommendations from this OR were implemented and we planned to assess systematically whether there were any improvements.

Objectives: Among patients with presumptive MDR-TB (July–December 2014), 1) to determine pre-diagnosis and pre-treatment attrition, 2) to determine factors associated with pre-diagnosis attrition, 3) to determine the turnaround time (TAT) from eligibility to testing and from diagnosis to treatment initiation, and 4) to compare these findings with those of the previous study (2012–2013).

Design: This was a retrospective cohort study based on record review.

Results: Compared to the previous study, there was a decrease in pre-diagnosis attrition from 45% to 24% (P < 0.001), in pre-treatment attrition from 29% to 0% (P = 0.18), in the TAT from eligibility to testing from a median of 11 days to 10 days (P = 0.89) and in the TAT from diagnosis to treatment initiation from a median of 38 days to 19 days (P = 0.04). There is further scope for reducing pre-diagnosis attrition by addressing the high risk of patients with human immunodeficiency virus and TB co-infection or those with extra-pulmonary TB not undergoing drug susceptibility testing.

Conclusion: The implementation of findings from OR resulted in improved programme outcomes.

Keywords: multidrug-resistant tuberculosis, diagnosis, delays, operational research, prevention, control

Abstract

Contexte : Une recherche opérationnelle basée sur un mélange de méthodes a été réalisée afin d'étudier le parcours de diagnostic et de traitement des patients atteints d'une tuberculose multirésistante (TB-MDR) présumée (2012–2013) dans le cadre du programme national TB, à Pondichéry, Inde. Nous avons identifié une attrition avant le diagnostic et avant le traitement, ainsi que les raisons de ce problème. Les recommandations de cette recherche opérationnelle ont été mises en œuvre et nous avons prévu d'évaluer systématiquement s'il y avait une amélioration.

Objectifs : Parmi les patients présumés atteints de TB-MDR (juillet–décembre 2014), 1) déterminer l'attrition pré-diagnostic et pré-traitement ; 2) déterminer les facteurs associés à l'attrition pré diagnostic ; 3) déterminer le délai depuis l'éligibilité jusqu'au test et du diagnostic à la mise en route du traitement ; et 4) comparer ces résultats à l'étude précédente.

Schéma : Etude de cohorte rétrospective impliquant une revue des dossiers.

Résultats : Par comparaison aux études précédentes, il y a eu une réduction de l'attrition pré-diagnostique de 45% à 24% (P < 0,001), une attrition pré-traitement de 29% à 0% (P = 0,18), un délai entre l'éligibilité au test d'une médiane de 11 jours contre 10 jours (P = 0,89) et un délai entre le diagnostic et la mise en route du traitement d'une médiane de 38 jours contre 19 jours (P = 0,04). Il y a des perspectives supplémentaires de réduction de l'attrition avant le diagnostic en ciblant les patients à risque de ne pas être testés parmi ceux atteints de TB et le virus de l'immunodéficience humaine et de TB extra-pulmonaire.

Conclusion : La mise en œuvre des résultats de la recherche opérationnelle a eu pour résultat une amélioration des résultats du programme.

Abstract

Marco de referencia: Se llevó a cabo una intervención de investigación operativa con métodos mixtos, con el fin de estudiar la trayectoria del diagnóstico y el tratamiento de los pacientes con presunción clínica de tuberculosis multirresistente (TB-MDR) en el 2012 y 2013 en el contexto del Programa Nacional contra la Tuberculosis de Puducherry, en la India. Se detectaron altas proporciones de abandono antes del diagnóstico y antes de comenzar el tratamiento y se analizaron sus causas. Las recomendaciones de esta investigación operativa se pusieron en práctica y en el presente estudio se prevé una evaluación sistemática que permita valorar si se logró algún progreso.

Objetivos: Analizar los siguientes resultados en los pacientes con presunción clínica de TB-MDR (de julio a diciembre del 2014): 1) si ocurrió abandono antes del diagnóstico o del tratamiento; 2) si existieron factores asociados con el abandono antes de definir el diagnóstico; 3) el lapso necesario entre el momento de la presunción clínica hasta la realización de las pruebas diagnósticas y desde la definición del diagnóstico hasta el comienzo del tratamiento; y 4) comparar estos resultados con los datos del estudio anterior.

Método: Fue este un estudio retrospectivo de cohortes, con análisis de las historias clínicas.

Resultados: En comparación con el estudio anterior, se observó una disminución del abandono antes del diagnóstico de 45% a 24% (P < 0,001) y antes del comienzo del tratamiento de 29% a 0% (P = 0,18); se redujo el lapso entre la presunción clínica y la práctica de las pruebas diagnósticas una mediana de 11 días a 10 días (P = 0,89) y también el lapso entre el diagnóstico y el inicio del tratamiento una mediana de 38 días a 19 días (P = 0,04). Existe aun margen para una mayor disminución de los abandonos anteriores al diagnóstico, si se aborda el alto riesgo de no practicar las pruebas diagnósticas a los pacientes coinfectados por el virus de la inmunodeficiencia humana y la TB y a los pacientes con TB extrapulmonar.

Conclusion: La aplicación de los resultados de la investigación operativa tuvo como consecuencia un progreso en los resultados del programa.

India's Revised National Tuberculosis Control Programme (RNTCP) adopted the global Stop TB Strategy recommended Programmatic Management of Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis (PMDT) for the effective delivery of drug-resistant tuberculosis (DR-TB) services.1,2 Studies worldwide have raised concerns over the high rates of pre-diagnosis and pre-treatment attrition and/or delays in the diagnosis and treatment pathway (DTP) for multidrug-resistant TB (MDR-TB).3–10 Of an estimated 71 000 MDR-TB cases among notified pulmonary TB patients in India in 2014 (~99 000 total estimated incidence),11 only 25 748 were notified, resulting in a case detection rate of 36%.12 Among notified MDR-TB cases, however, more than 90% were initiated on treatment.13

Given the limited cohort-related information available within the programme, a mixed-methods operational research (OR) study was conducted by the RNTCP in Puducherry, India, to evaluate the DTP among patients with presumptive MDR-TB from October 2012 to September 2013.14 Pre-diagnosis and pre-treatment attrition were respectively 45% and 29%. To address these issues, based on the recommendations made in the study, several actions were taken, including:14 1) improving the mechanisms for tracking referrals: setting up and strengthening the use of referrals for the culture and drug susceptibility testing (DST) register at the district TB centre; consistent recording of TB registration numbers on the referral form for culture and DST and in the diagnostic facility laboratory register to enable tracking; and making cohort analysis part of routine monitoring for PMDT services; 2) health systems strengthening: training and re-sensitising the staff of general health-care delivery systems, especially the laboratory technicians in the designated microscopy centres; and 3) developing a mechanism of sputum transport from the designated microscopy centre to the DST diagnostic facility.

To systematically assess whether there were any improvements following these actions, we conducted a follow-up study among patients with presumptive MDR-TB during July–December 2014 using the same methodology as in the previous study.14 The specific objectives of the present study were: 1) to determine pre-diagnosis and pre-treatment attrition, 2) to determine factors associated with pre-diagnosis attrition, 3) to determine the turnaround time (TAT) from eligibility to testing and from diagnosis to treatment initiation, and 4) to compare these findings with those of the previous study.

METHODS

The study setting, design, study variables and their operational definitions, sources of data, data collection, data management and statistical analyses are similar to the quantitative part of our previous study, and have been described elsewhere.14* The protocol for the DTP in Puducherry was the same for the previous and the present study, except for the implementation of the recommendations from the previous study into the present study. The salient points have been described here.

The study population consisted of patients with presumptive MDR-TB with a date of eligibility for DST between July and December 2014. Similar to the previous study, patients with presumptive MDR-TB included the following among all notified TB cases in the programme (bacteriologically/clinically diagnosed, pulmonary TB [PTB], extra-pulmonary TB [EPTB] cases, new/retreatment cases): 1) all patients with retreatment TB, 2) any follow-up smear-positive cases, 3) new patients with PTB who were contacts of known patients with MDR-TB, and 4) all TB and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) co-infection cases at diagnosis.14

The mechanisms for routine transportation of specimens, communicating the results to the district TB centre, reporting the results to patients and enrolling patients with MDR-TB on DR-TB treatment were all similar to those previously described.14 The programme staff felt that as Puducherry was a small geographical area, sputum transportation was not required. Because it was identified in the previous study that patients from hard-to-reach primary health centres (PHCs) could have had problems reaching the laboratory, in the present study, local voluntary non-governmental organisations were recruited for the transport of specimens per programme guidelines. In the DST diagnostic facility, as has been previously described, the line probe assay (LPA) was used upfront for smear-positive sputum samples. For smear-negative samples and invalid LPA results of smear-positive samples, culture was performed, followed by LPA if positive. In the case of contaminated samples, a repeat sample was requested.14

Data were collected during January–May 2016. We tracked each presumptive MDR-TB patient in the records for 3 months from the date of eligibility until diagnosis—extended by an additional 3 months for smear-negative samples and invalid LPA results on smear-positive samples—and 3 months post-diagnosis, if positive for MDR-TB, until treatment initiation.

The decreases in pre-diagnosis attrition and pre-treatment attrition between the previous study (October 2012–September 2013) and the present study (July–December 2014) were compared using the χ2 test or Fisher's exact test, as appropriate. The Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare the decrease in the median TAT (in days) from the date of eligibility to DST and from diagnosis to treatment.

Ethics

Ethics approval was obtained from the Ethics Advisory Group of the International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease, Paris, France. As the study involved retrospective review of patient records, a waiver for the need for informed consent was requested and approved. Administrative permission to access the data was obtained from the RNTCP, Puducherry, India.

RESULTS

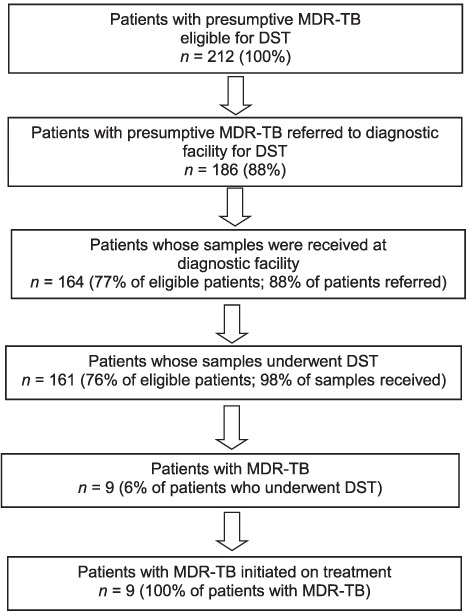

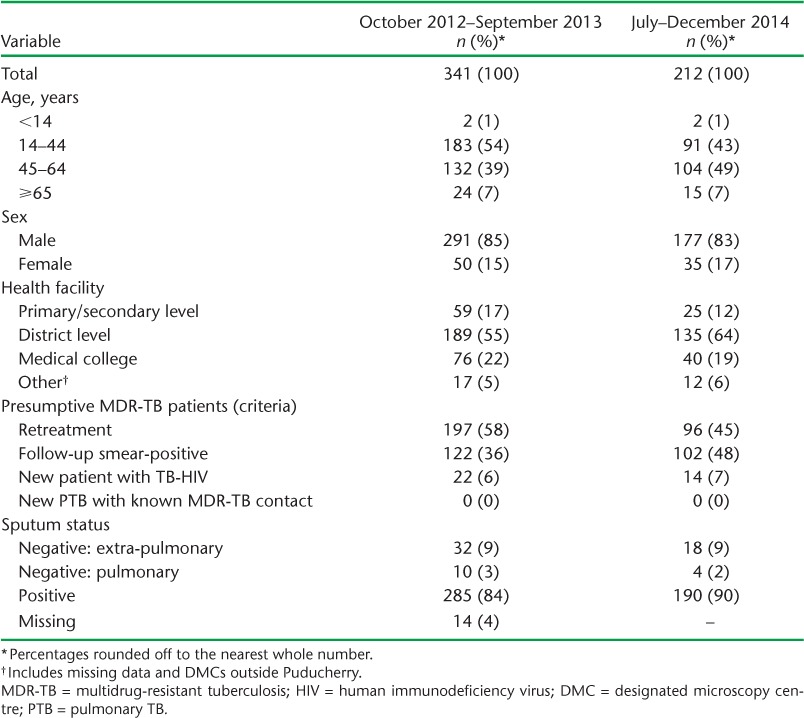

Of 212 patients with presumptive MDR-TB eligible for DST, 88% (186/212) were referred by the RNTCP. The samples of 88% (164/186) reached the DST diagnostic facility, of which 161 (98%) were tested. Pre-diagnosis attrition was 24% (51/212) among eligible patients. After excluding patients with EPTB (n = 18) from the cohort, pre-diagnosis attrition was 18% (34/194). The nine patients with MDR-TB were initiated on treatment (Figure). The baseline characteristics of the study participants in the previous14 and present study are summarised in Table 1.

FIGURE.

Flow of patients with presumptive MDR-TB in the diagnosis and treatment pathway, Puducherry, India, July–December 2014. MDR-TB = multidrug-resistant tuberculosis; DST = drug susceptibility testing.

TABLE 1.

Clinical and sociodemographic characteristics of patients with presumptive MDR-TB in previous (October 2012–September 2013)14 and present (July–December 2014) study, Puducherry, India

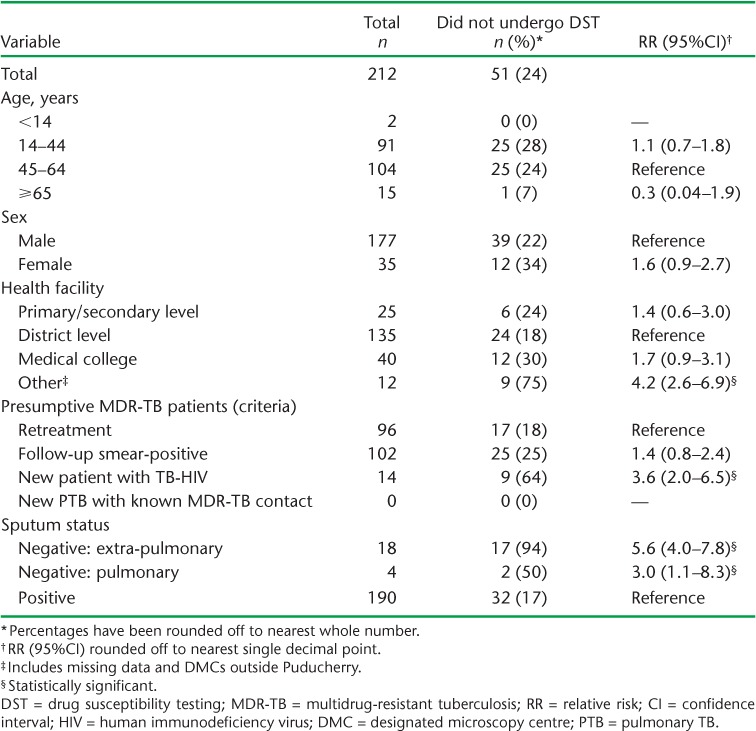

New patients co-infected with TB-HIV at diagnosis had a higher risk of not undergoing DST than retreatment patients (relative risk [RR] 3.6, 95% confidence interval [CI] 2.0–6.5), as did patients with EPTB (RR 5.6, 95%CI 4.0–7.8) and smear-negative PTB (RR 3.0, 95%CI 1.1–8.3) compared to patients with pulmonary TB (Table 2). The median TAT from eligibility to DST and from MDR-TB diagnosis to treatment initiation were respectively 10 days (IQR 6–22) and 19 days (IQR 16–31) (Table 3).

TABLE 2.

Clinical and sociodemographic factors associated with not undergoing DST among patients with presumptive MDR-TB, July–December 2014, Puducherry, India

TABLE 3.

Comparison of attrition and TAT among patients with presumptive MDR-TB before (October 2012–September 2013) and after (July–December 2014) implementation of recommendations * , Puducherry, India

Compared to the previous study, there was a decrease in pre-diagnosis attrition from 45% to 24% (P < 0.001) and in pre-treatment attrition from 29% to 0% (P = 0.17). While the decrease in the median TAT from eligibility to DST from 11 to 10 days was not significant (P = 0.89), there was a significant decrease in the median TAT from diagnosis to treatment initiation from 38 to 19 days (P = 0.04) (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

The recommendations made by the RNTCP based on the OR study among patients with presumptive MDR-TB in Puducherry, India,14 were promptly implemented. This led to a decrease in pre-diagnosis attrition, pre-treatment attrition and the TAT from MDR-TB diagnosis to treatment initiation.

Most of the decrease in pre-diagnosis attrition was contributed by an improvement in the gap between patient referral and reaching the DST diagnostic facility, as previously identified.14 In the present study, post-referral attrition contributed to 51% (26/51) of pre-diagnosis attrition compared to 70% (108/155) in the previous study. Although the number of patients with MDR-TB was lower in both cohorts, we observed a decrease not only in pre-treatment attrition, but also in the time taken to initiate treatment. We speculate that this could result in better MDR-TB treatment outcomes. An analysis of the treatment outcomes for patients with MDR-TB registered between 2012 and 2014 is now recommended.

While the effect of OR on policy and practice has been studied before through self-administered questionnaires sent by e-mail,15,16 a follow-up OR study to systematically document the results would be preferable. We started with an OR study in 2013, published the results in 2015, and ultimately ended up with a change in practice in the programme. The constructive approach of the programme manager is appreciated.

There is, however, further scope for reducing pre-diagnosis attrition, and the programme is committed to addressing this by focusing on patients with TB-HIV, EPTB and smear-negative PTB who were at high risk of not undergoing DST in both the previous study and the present study.14 Among 18 presumptive MDR-TB patients with EPTB, only one was identified and referred for DST. For EPTB, it was not clear even in the national PMDT guidelines as to which specimens should be collected or the methods for storage and processing before sending the specimens to the laboratory.2 Recently released technical and operational guidelines have incorporated this point.17 The programme may consider capacity building for the DST diagnostic facility in Puducherry or sending the EPTB samples to the Supranational Reference Laboratory in Chennai, 160 km from Puducherry.

Limitations

There were some limitations in this study, which were similar to those in our previous study.14 We did not have sufficient numbers of patients with MDR-TB to identify factors associated with pre-treatment attrition. The occurrence of new MDR-TB cases among contacts of patients with presumptive/confirmed MDR-TB with a delay in DTP was beyond the purview of this study. No patients met the criterion ‘patients in close contact with known MDR-TB’, but this information was not systematically captured in the programme records. Factors for pre-diagnosis attrition were identified through a programme perspective. Barriers related to access, including distance from patient's residence to diagnostic facility and to DR-TB centre and travel costs, were not recorded, as this information was not routinely collected. While there are inherent limitations in record review studies, the RNTCP records are monitored and supervised, and this includes periodic data validation.

Strengths

The study had several strengths. The methodology used was sound, with pre-defined operational definitions and a clear follow-up period defined for record review that was the same for each eligible referral. As double data entry and validation were performed, the data were quality assured and robust. As we studied the entire population of patients with presumptive MDR-TB without any sampling, the results are likely to be representative and reflect the reality in the field. We followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines to report the findings of the study.8

CONCLUSION

This study provides evidence that implementation of findings from an OR study can result in improved programme outcomes. OR should become part of routine programme implementation, as it is conducted within programmatic settings using existing staff and resources, putting no financial burden on the programme.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the support of the Revised National Tuberculosis Control Programme staff (Puducherry, India) who helped perform the record review. As this study was conducted as an operational research study under the programme conditions using programme staff, no separate budget was required. La Foundation Veuve Emile Metz-Tesch supported the open access publication costs. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript. The authors thank the Department for International Development (London, UK) for funding the Global Operational Research Fellowship Programme in which HDS works as an operation research fellow.

Footnotes

* The database, along with the codebook and the programme used for the analyses, can be obtained from the Corresponding author on request.

Conflicts of interest: none declared.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. The Stop TB strategy: building on and enhancing DOTS to meet the TB-related Millennium Development Goals. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2006. WHO/HTM/STB/2006.37. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Revised National Tuberculosis Control Programme. Central TB Division. Guidelines on programmatic management of drug-resistant TB in India. New Delhi, India: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Qi W, Harries A D, Hinderaker S G. Performance of culture and drug susceptibility testing in pulmonary tuberculosis patients in northern China. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2011;15:137–139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abeygunawardena S C, Sharath B N, Van den Bergh R et al. Management of previously treated tuberculosis patients in Kalutara district, Sri Lanka: how are we faring? Public Health Action. 2014;4:105–109. doi: 10.5588/pha.13.0111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chadha S S, Sharath B N, Reddy K et al. Operational challenges in diagnosing multidrug-resistant TB and initiating treatment in Andhra Pradesh, India. PLOS ONE. 2011;11:e26659. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harries A D, Michongwe J, Nyirenda T E et al. Using a bus service for transporting sputum specimens to the Central Reference Laboratory: effect on the routine TB culture service in Malawi. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2004;8:204–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khann S, Mao E T, Rajendra Y P et al. Linkage of presumptive multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) patients to diagnostic and treatment services in Cambodia. PLOS ONE. 2013;8:e59903. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0059903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kilale A M, Ngowi B J, Mfi G S et al. Are sputum samples of retreatment tuberculosis reaching the reference laboratories? A 9-year audit in Tanzania. Public Health Action. 2013;3:156–159. doi: 10.5588/pha.12.0103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li Y, Ehiri J, Oren E et al. Are we doing enough to stem the tide of acquired MDR-TB in countries with high TB burden? Results of a mixed method study in Chongqing, China. PLOS ONE. 2014;9:e88330. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0088330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Singla N, Satyanarayana S, Sachdeva K S et al. Impact of introducing the line probe assay on time to treatment initiation of MDR-TB in Delhi, India. PLOS ONE. 2014;9:e102989. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0102989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis control. WHO report 2010. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2010. WHO/HTM/TB/2010.7. [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis report, 2015. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2015. WHO/HTM/TB/2015.22. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Revised National Tuberculosis Control Programme. Central TB Division. TB India 2016. Annual status report. New Delhi, India: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shewade H D, Govindarajan S, Sharath B et al. MDR-TB screening in a setting with molecular diagnostic techniques: who got tested, who didn't and why? Public Health Action. 2015;5:132–139. doi: 10.5588/pha.14.0098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kumar A M V, Shewade H D, Tripathy J P et al. Does research through Structured Operational Research and Training (SORT IT) courses impact policy and practice? Public Health Action. 2016;6:44–49. doi: 10.5588/pha.15.0062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zachariah R, Guillerm N, Berger S et al. Research to policy and practice change: is capacity building in operational research delivering the goods? Trop Med Int Health. 2014;19:1068–1075. doi: 10.1111/tmi.12343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Revised National Tuberculosis Control Programme. Central TB Division. Technical and operational guidelines for tuberculosis control in India. New Delhi, India: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 18.von Elm E, Altman D G, Egger M et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet. 2007;370:1453–1457. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61602-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]