Abstract

Setting: Eight village development committees of Mugu District, a remote mountainous district of Nepal that has poor maternal health indicators.

Objectives: 1) To assess the proportion of mothers who delivered in health facilities (institutional delivery); 2) among mothers who delivered at home, to understand their reasons for doing so; and 3) among mothers who delivered in health facilities, to understand their challenges.

Design: Cross-sectional study involving semi-structured interviews with mothers conducted in 2015.

Results: Of 275 mothers, 97 (35%) had an institutional delivery. Multivariate logistic regression analysis showed that women who resided within 1 h distance from the birthing centre, had adequate mass media exposure or had only one child were more likely to deliver in hospital. Reasons for non-institutional delivery (n = 178) were related to geographical access (49%), personal preferences (18%) and perceived poor quality care (4%). Mothers who accessed institutional delivery (n = 97) also reported difficulties related to travel (60%), costs (28%), dysfunctional health system (18%) and unfriendly attitudes of the health-care providers (7%).

Conclusion: To improve access to institutional delivery, the government should establish a 24/7 emergency ambulance network, including air ambulance. Health system issues, including unfriendly staff attitudes, urgently need to be addressed to gain the trust of the mothers.

Keywords: access, challenges, health-care provider behaviour

Abstract

Contexte : Huit comités de développement villageois de Mugu, un district de montagne isolé du Népal avec des indicateurs de santé maternelle médiocres.

Objectifs : 1) Evaluer la proportion de mères qui ont accouché dans des structures de santé (accouchement en institution), 2) comprendre les raisons de celles qui ont accouché à domicile, et 3) comprendre les défis qu'ont affronté les mères qui ont accouché dans des structures de santé.

Schéma : Etude transversale impliquant des entretiens semi-structurés de mères réalisés en 2015.

Résultats : Sur 275 mères, 97 (35%) ont accouché en institution. Une analyse de régression logistique multivariée a montré que les femmes qui résidaient à une distance de moins d'une heure du centre d'accouchement, avaient une exposition suffisante aux media ou avaient un seul enfant étaient plus susceptibles d'accoucher dans un hôpital. Les motifs d'accouchement hors institution (n = 178) ont été liés à l'accès géographique (49%), aux préférences personnelles (18%) et à une perception de la qualité médiocre des soins (4%). Les mères qui ont eu accès à l'accouchement en institution (n = 97) ont également fait part des difficultés liées au transport (60%), au coût (28%), à un système de santé fonctionnant mal (18%) et à des attitudes désagréables des prestataires de soins de santé (7%).

Conclusion : Pour améliorer l'accès, le gouvernement devrait établir un réseau d'ambulances d'urgence disponible en permanence, y compris un transport aérien. Les problèmes liés au système de santé, notamment l'attitude désagréable du personnel, doivent être abordés d'urgence afin de gagner la confiance des mères.

Abstract

Marco de referencia: Ocho comités de desarrollo de las aldeas en Mugu, un remoto distrito montañoso de Nepal que presenta indicadores de salud materna insatisfactorios.

Objectivos: 1) Evaluar la proporción de madres cuyo parto se atendió en los establecimientos de salud (parto institucional); 2) comprender las razones de las madres cuyo parto tuvo lugar en el hogar; 3) comprender las dificultades de las madres atendidas en los establecimientos de salud.

Método: Fue este un estudio transversal con entrevistas semiestructuradas a las madres, realizado en el 2015.

Resultados: De las 275 mujeres que participaron, 97 tuvieron un parto institucional (35%). El análisis de regresión logística multivariante reveló que el parto intrahospitalario era más frecuente en las mujeres que residían a menos de una hora de distancia del centro de maternidad, que contaban con una exposición adecuada a los medios de información o que tenían un solo hijo. Las razones del parto domiciliario (n = 178) guardaron relación con el acceso geográfico (49%), las preferencias personales (18%) y la percepción de una atención de baja calidad (4%). Las madres que accedieron al parto institucional (n = 97) refirieron además dificultades relacionadas con el desplazamiento (60%), los costos (28%), las deficiencias del sistema de salud (18%) y las actitudes poco amables de los profesionales de salud (7%).

Conclusión: Con el propósito de mejorar el acceso, el gobierno debería poner en funcionamiento una red permanente de ambulancias de urgencia, que cubra también los desplazamientos aéreos. Es urgente abordar los problemas provenientes del sistema de salud como la actitud hostil del personal, a fin de ganar la confianza de las madres.

In 1997, the Government of Nepal commenced a Safe Motherhood Programme to improve maternal health in the country. Through these efforts, Nepal was able to significantly reduce the maternal mortality ratio (MMR) from 850 in 1990 to 229 in 2008.1 Progress made so far at the end of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) 2015 deadline suggests that the goals related to maternal health are achievable.2 Recent estimates for 2015, however, show that Nepal still has the highest MMR in the South Asia region.3

The main reasons for maternal death are post-partum haemorrhage, eclampsia, abortion complications, obstructed labour and puerperal sepsis.4 To address these causes, it is essential that mothers deliver in health facilities (institutional delivery).

A 2008 study reported that the MMR was higher and the availability of health-care providers and the functionality of birthing centres were lower in Nepal's mountain districts compared to other districts.1 While the proportion of institutional deliveries increased in Nepal, from 9% in 2001 to 35% in 2011, the proportion remained low, at 15% in 2011, for the Western mountain districts.5,6

It is crucial to achieve universal institutional delivery to further reduce the MMR. Although significant efforts have been made by the Nepal Health Sector Support Programme, including providing travel incentives for mothers to improve institutional delivery rates, progress has not been consistent. There is limited understanding as to why the frequency of institutional delivery has not improved in the mountain districts compared to other parts of the country. Studies from rural areas of South Asia have reported the influence of economic status,7 parity and education on the utilisation of institutional delivery.8 This is important to understand in an area where the physical remoteness of the mountain regions restricts access to service centres due to poorly developed basic infrastructures.9

Previous studies from Nepal have mainly been conducted in non-mountainous districts and have highlighted barriers related to institutional delivery, such as long walking distances, unavailability of transport, unavailability of staff, low education levels, lack of awareness of delivery care and cost.10–12 The utilisation of maternal health services is also greatly influenced by the quality of the service delivery centres.13

Given the dearth of evidence from the mountain regions, this study could serve policy makers and programme managers in reviewing the approaches used in meeting the MDGs and in developing a customised strategy for mountain regions to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals.14 Very few studies have explored and reported the perspectives of mothers who delivered at health facilities and those who did not. We therefore sought to understand the perspectives of women residing in a remote mountain district of Nepal on challenges related to delivering in a health facility.

The specific objectives were to assess, among a sample of married women of reproductive age (hereafter referred as mothers) residing in Mugu District, Nepal, 1) the proportion who delivered at a health facility; 2) sociodemographic and clinical characteristics associated with institutional delivery; 3) among mothers who did not deliver in a health facility, reasons for non-institutional delivery; and 4) among mothers who delivered in a health facility, the challenges they faced.

METHODS

Study design

This was a cross-sectional study involving interviews with mothers at their homes, and is part of a larger study that used both quantitative and qualitative methods to collect data (unpublished). We report only the findings from the quantitative data in this paper; the findings of the qualitative component will be reported separately.

Setting

Nepal is a landlocked country in Asia with 75 districts, including 16 mountain districts. Each district is further subdivided into village development committees (VDCs), each of which consists of nine wards. The number of VDCs in each district ranges from 13 to 107; each VDC has a health facility that may or may not be a birthing centre.

The study was conducted in eight of the 24 VDCs in Mugu District, which is located in the remote mountain region of western Nepal. Mugu District has a population of ~55 000, of whom ~10 000 are ever-married females aged between 15 and 49 years who have ever delivered a child.15 Mugu District has one of the lowest human development indexes (0.397) in the country.16

Safe Motherhood Programme

In 1997, the Government of Nepal implemented the Safe Motherhood Programme countrywide. The programme focuses on three aspects: 1) promoting birth preparedness and complication readiness, including awareness raising and improving the availability of funds, transport and blood supplies; 2) encouraging institutional delivery; and 3) expanding 24-h emergency obstetric care services (basic and comprehensive) at selected public health facilities in every district. The services are provided free of charge. To improve the uptake of services, the government also provides the transportation costs of 1500 Nepalese rupees (~US$14) to women delivering at the health facility.

Study population and study period

The study population consisted of mothers residing in the study area who had delivered a child in the past 5 years. The study was carried out from February to March 2015.

Sampling and sample size

A household survey was conducted to collect the data. Assuming a proportion of 0.74 with an alpha of 0.5 for a finite population, we estimated a total sample of 360 married women of reproductive age, of whom 270 had delivered in the 5 years preceding the survey.

We used a two-stage cluster sampling technique to select the households. The primary sampling unit was the village ward. In the first stage, we randomly selected 18 wards of eight VDCs. In the second stage, 20 households were randomly selected in each village ward. If there was more than one mother in a household, the mother with the youngest child was selected.

Data collection, entry and analysis

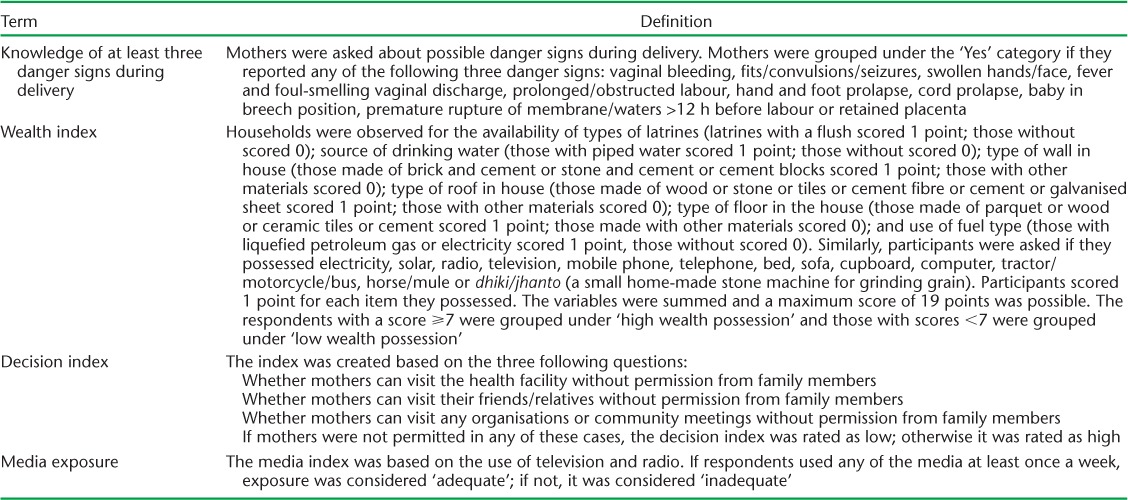

Each mother was interviewed by a trained researcher using a pre-tested, semi-structured questionnaire. Key variables included sociodemographic characteristics, knowledge about the availability of maternal health services, barriers to accessing place of delivery and reasons for non-institutional delivery. The study also used indices such as wealth possession, knowledge of at least three danger signs related to delivery, decision-making power to access the health service and mass media exposure. The operational definitions of these variables are defined in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Operational definitions of indices used in the study, Mugu District, Nepal, 2015

Each completed questionnaire was manually checked and coded. Double data entry and validation were performed using CSPro version 5.0 (US Census Bureau, Washington, DC, USA). The data were then cleaned and analysed using IBM PASW version 20.0 (IBM Corp, Montauk, NY, USA). Bivariate analysis using the χ2 test was performed to assess factors associated with place of delivery. Factors found to be significant on bivariate analysis (P < 0.2) were included in a multivariable logistic regression model to assess the independent effect of each variable. The findings are presented as odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Multicollinearity was checked among the independent variables, and goodness of fit was performed prior to fitting into the model.

Ethics

Ethics approval was obtained from the Nepal Health Research Council, Kathmandu. In the district, administrative approval was obtained from the district authorities and all study health facilities. Written informed consent was obtained from the study participants. All precautions were taken to maintain data confidentiality.

RESULTS

Sociodemographic characteristics of study participants

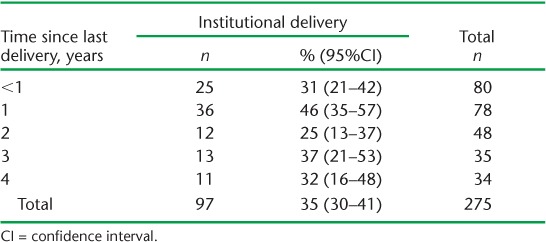

Of the total 275 mothers, 35% (95%CI 30–41) had had their most recent delivery at a health facility (Table 2). However, the proportion of institutional deliveries did not improve over the 4 years.

TABLE 2.

Institutional delivery by mothers disaggregated by time since last delivery in Mugu District, Nepal, 2015 (N = 275)

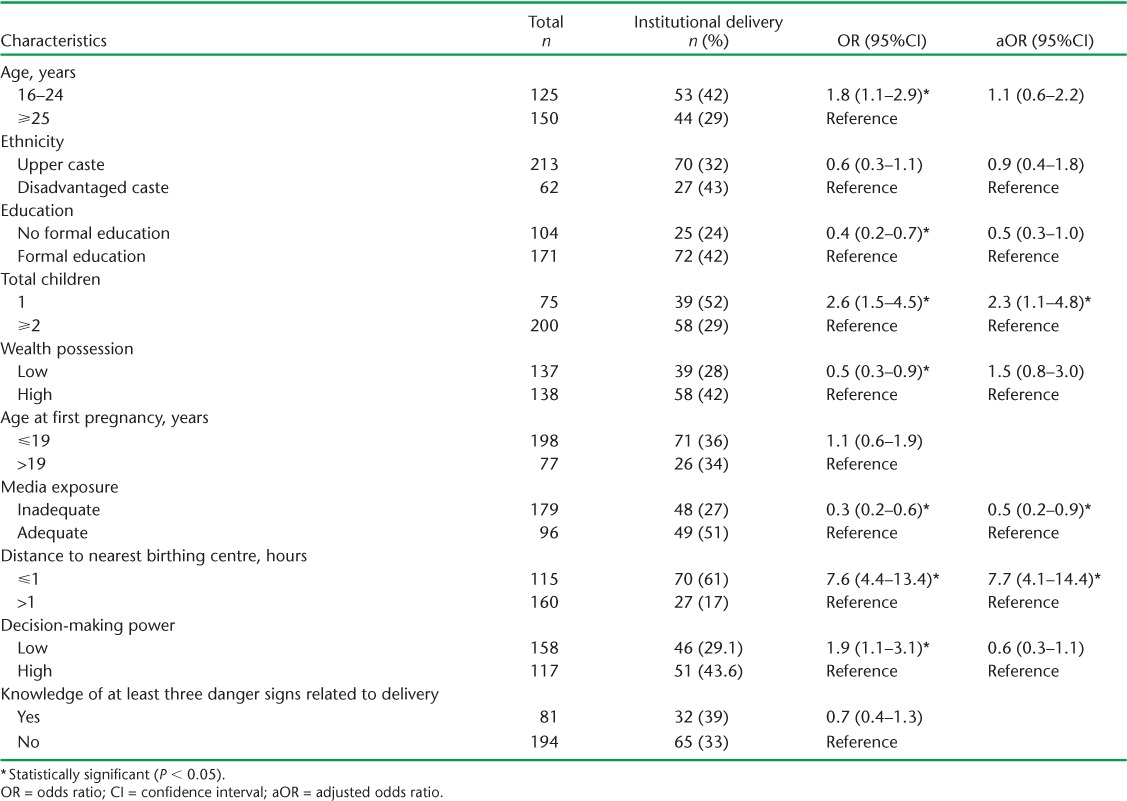

The sociodemographic characteristics of the study population are shown in Table 3. The median age of the mothers was 25 years (interquartile range [IQR] 21–30). About a quarter of the mothers belonged to disadvantaged castes, a third had no formal education and half belonged to the low-income category. Two thirds had inadequate exposure to media and more than half had low decision-making power. About 60% of the mothers had to travel for more than 1 h using the fastest available means of transport to reach the nearest birthing centre. Around 70% of the mothers had no knowledge of at least three danger signs during delivery. The median age at marriage was 16 years (IQR 15–18); most mothers had their first pregnancy before the age of 19 years.

TABLE 3.

Sociodemographic characteristics associated with institutional delivery among mothers in Mugu District, 2015 (N = 275)

Factors associated with institutional delivery

Factors associated with institutional delivery are shown in Table 3. In bivariate analysis, age, formal education, wealth possession, media exposure, number of children, decision-making power and time taken to travel to the nearest birthing centre were significantly associated with institutional delivery. Mothers aged <25 years were significantly more likely to deliver in a health facility compared to those aged ⩾25 years. Mothers with no formal education, low wealth possession, low decision-making power, inadequate media exposure and those residing further away from the birthing centre were less likely to deliver in a health facility.

The results of the multivariate analysis are shown in Table 3. Factors found to be associated on bivariate analysis were included in the multivariate model. As age and number of children were correlated, ‘number of children’ was included in the final model. In the model, primiparous mothers had higher odds of institutional delivery (adjusted OR [aOR] 2.3, 95%CI 1.1–4.8) than multiparous mothers. Similarly, mothers with inadequate exposure to the media had lesser odds of institutional delivery (aOR 0.5, 95%CI 0.2–0.9) than mothers with adequate exposure. Another significantly associated predictor was distance; mothers residing within a travel distance of 1 h had higher odds of delivering at the health facility (aOR 7.7, 95%CI 4.1–14.4) than mothers residing at a greater distance.

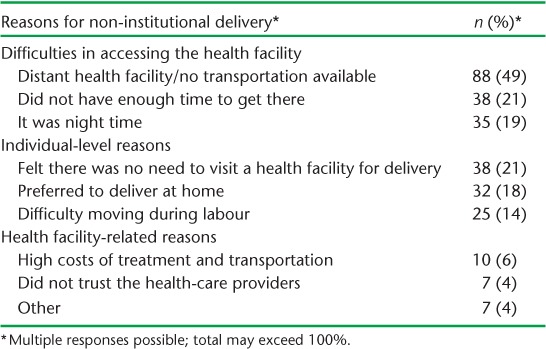

Reasons for non-institutional delivery

The reasons for non-institutional delivery are shown in Table 4. Most mothers had difficulties accessing the health facility; nearly half reported the distant location of the health facility, 21% said that they had insufficient time to reach the health facility and 19% had labour pains that started at night and could not arrange transport. Some mothers (21%) felt that there was no need to visit the health facility for a normal life event such as delivery, and 18% said that they preferred to deliver at home. The other main reason was related to the high costs associated with transport and treatment at the health facility (6%).

TABLE 4.

Reasons for non-institutional delivery given by mothers who did not deliver in a health facility in Mugu District, Nepal, 2015 (N = 178)

Difficulties experienced in accessing delivery care services

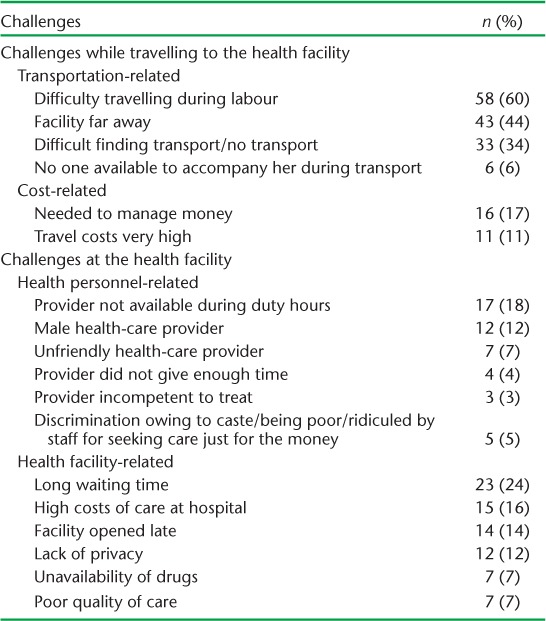

Difficulties faced by those mothers who delivered at the health facilities are shown in Table 5. Mothers mostly reported transportation-related difficulties, such as difficulty in travelling during labour (60%), having to walk long distances and using public transport (often inconvenient) to travel to the health facility. They also faced difficulties in managing money (17%) and assuming the transportation costs (11%).

TABLE 5.

Challenges faced by mothers who delivered at a health-care facility during their last delivery in Mugu District, Nepal, 2015 (N = 97)

Other difficulties were related to the health facility: long waiting times before meeting the health-care providers (24%) and the late opening times (14%). Some mothers (7%) reported poor quality of the service and unavailability of drugs. About 18% of mothers reported that health-service providers were not present during opening hours and 12% were not comfortable being treated by male health-care providers. Some mothers reported unfriendly behaviour of health-care providers (7%) and discriminatory attitudes (4%).

DISCUSSION

Only one third of women in Mugu District deliver in a health facility, despite the efforts of the Government of Nepal; this low proportion could be an overestimate, as the study sites were clustered around the district headquarters and did not include some of the more remote areas. Nevertheless, our findings indicate some progress compared to 2011, when only 16% of women in mountain districts delivered at health facilities.

The main reasons for mothers not delivering in a health facility were related to geographical access (distance to the nearest birthing centre, lack of transportation services, high transportation costs); perceived poor quality care and unfriendly health-care providers; and a personal preference for home delivery. Likewise, multiparity, low media exposure and distance were also found to lower the odds of delivering at a health facility. Geographical distance is still preventing mothers from utilising institutional delivery services despite the government's efforts to improve the road network and transportation services. Personal preference to deliver at an institution needs to be linked with the evidence that higher media exposure is reported to have increased the likelihood of utilising maternal health services,17 including institutional deliveries.18

Mothers who delivered at a health facility faced a number of difficulties: managing transportation and related costs, unsatisfactory behaviour of health workers, long waiting times and lack of privacy. These difficulties call into question the quality of care,19 and may deter mothers from seeking institutional services in the future, preferring home delivery, mostly with unskilled birth attendants. The low likelihood of multiparous mothers delivering at a facility20 may be related to challenges they faced in previous deliveries at a health facility.

Strengths

This study has several strengths. This the first study from a mountain district of Nepal to explore not only barriers among women who did not deliver in a health facility but also challenges faced by women who did. We took several steps to ensure the quality of the data: data collection was performed by trained female public health graduates, daily supervision was undertaken to ensure the completeness and consistency of the questionnaire, pre-tested tools for data collection and double data entry were used to mini-mise data entry errors and we followed the STrengthening the Reporting of OBservational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement guidelines for reporting the study.21

Limitations

The study has some limitations. First, it was carried out in eight (of 24) selected VDCs of Mugu District, and may not be representative of the situation in the whole district. Second, the study sites were clustered around the district headquarters, thereby possibly overestimating the proportion of institutional deliveries. Third, as we interviewed mothers who had delivered within the past 5 years, there could have been recall limitations. The study results are therefore a summary of the situation in the past 5 years rather than the current situation. This limitation could have been avoided if we had sampled only those mothers who had delivered in the past year. Previous studies, however, including the National Demographic and Health Survey,3 have used the same methodology, allowing us to compare study findings. Finally, given the small sample size, we could not explore interactions between the variables in the multivariable analysis.

Policy implications

The study findings have a number of policy implications. The main challenge identified was physical access to the health facilities, particularly due to difficult geographical terrain in the mountains, with poor road transport. Policy makers therefore need to seriously consider developing a tailor-made approach for mountain districts such as Mugu District, where despite the availability of free maternal care and transport incentives, most mothers choose to deliver at home. We recommend that there should be an emergency ambulance network, which includes air ambulances operating round the clock. There should be a national toll-free phone number for health emergencies that people can call and request ambulance services. Such measures have been shown to be effective in reducing maternal and neonatal mortality in Africa.22 The other measure is to establish a ‘shelter house’ near the birthing centre where mothers can stay for a few days before the expected date of delivery.

The government should also consider contracting skilled birth attendants for remote wards. Furthermore, the transport incentive has not been revised since its inception in 2004: it is grossly inadequate to cover the high transportation costs and needs revision for mountainous regions.

The other important aspect reflected in the study was the lack of trust in the health-care delivery system. District health authorities need to ensure the availability of competent and patient-friendly staff, supplies, drugs and functional health facilities. The unfriendly and discriminatory attitude of health-care providers towards mothers urgently needs to be addressed, otherwise this could set back the ongoing efforts and investment to improve maternal health by the Government of Nepal.

CONCLUSION

We found low rates of institutional delivery by mothers, due mainly to geographic inaccessibility. In addition, we found issues related to staff behaviour and the overall quality of services at hospitals. Tailor-made strategies for remote areas are required, which may include developing emergency air-ambulances and recruiting skilled birth attendants at ward level to assist home deliveries. It is equally important to enhance the quality of care services at the health facility level to build up trust among beneficiaries.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the technical and financial support received from the Korean International Cooperation Agency (KOICA) Gyeonggi-do, Republic of Korea. They would also like to acknowledge H Jung and all the study team for their help in accomplishing the project. They are thankful to Family Health Division (Ministry of Health and Population, Kathmandu, Nepal), District Health Office, Mugu, and all the study participants, without whom this study would not have been possible.

This paper was produced as a result of a paper writing workshop facilitated by faculty from the Centre for Operational Research, International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease (The Union), Paris, France; The Union South-East Asia Regional Office, New Delhi, India; and the Operational Research Unit, Médecins Sans Frontières, Luxembourg. We would also like to thank N Ashra-McGrath for helping to facilitate the workshop and for editorial support.

The costs for open access publication were funded by COMDIS-HSD, a research consortium funded by aid from the UK government. The views expressed, however, do not necessarily reflect the UK government's official policies.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: none declared.

References

- 1.Suvedi B K, Pradhan A, Barnett S Nepal maternal mortality and morbidity study 2008/2009: summary of preliminary findings. Kathmandu, Nepal: Ministry of Health; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nepal National Planning Commission. Nepal Millennium Development Goals Progress Report 2013. Kathmandu, Nepal: NPC; 2013. http://www.np.undp.org/content/dam/nepal/docs/reports/millennium%20development%20goals/UNDP_NP_MDG_Report_2013.pdf Accessed December 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. Trends in maternal mortality: 1990 to 2015. Estimates by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank Group and the United Nations Population Division. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2015. http://data-topics.worldbank.org/hnp/files/TrendsinMaternalMortality1990to2015fullreport.PDF Accessed September 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization. Maternal mortality. Fact sheet. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2016. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs348/en/ Accessed December 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nepal Ministry of Health and Population. Nepal Demographic and Health Survey, 2011. Kathmandu, Nepal: Ministry of Health and Population; 2011. http://un.org.np/data-coll/Health-Publications/2011_NDHS.pdf Accessed September 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nepal Ministry of Health. Nepal Demographic and Health Survey, 2001. Kathmandu, Nepal: Ministry of Health; 2002. https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR132/FR132.pdf Accessed September 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kesterton A J, Cleland J, Sloggett A, Ronsmans C. Institutional delivery in rural India: the relative importance of accessibility and economic status. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2010;10:30. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-10-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Agha S, Carton T W. Determinants of institutional delivery in rural Jhang, Pakistan. Int J Equity Health. 2011;10:31. doi: 10.1186/1475-9276-10-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heeks R, Kanashiro L L. Telecentres in mountain regions – a Peruvian case study of the impact of information and communication technologies on remoteness and exclusion. JMS. 2009;6:320–330. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baral Y R, Lyons K, Skinner J, Van Teijlingen E R. Determinants of skilled birth attendants for delivery in Nepal. Kathmandu Univ Med J. 2010;8:325–332. doi: 10.3126/kumj.v8i3.6223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dhakal S, van Teijlingen E, Raja E A, Dhakal K B. Skilled care at birth among rural women in Nepal: practice and challenges. J Health Popul Nutr. 2011;29:371–378. doi: 10.3329/jhpn.v29i4.8453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shrestha S K, Banu B, Stray-Pedersen B et al. Changing trends on the place of delivery: why do Nepali women give birth at home? Reprod Health. 2012;9:25. doi: 10.1186/1742-4755-9-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Acharya L, Cleland J. Maternal and child health services in rural Nepal: does access or quality matter more? Health Policy Plan. 2000;15:223–229. doi: 10.1093/heapol/15.2.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.United Nations. Sustainable Development Goals. NY, New York, USA: UN; 2016. http://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/ Accessed December 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nepal Central Bureau of Statistics. National population and housing census, 2011. Kathmandu, Nepal: CBS; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nepal National Planning Commission. Nepal Human Development Report, 2014. Beyond geography. Unlocking human potential. Kathmandu, Nepal: NPC; 2014. http://www.npc.gov.np/images/download/NHDR_Report_2014.pdf Accessed September 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Simkhada B, Van Teijlingen E R, Porter M, Simkhada P. Factors affecting the utilization of antenatal care in developing countries: systematic review of the literature. J Adv Nurs. 2008;61:244–260. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04532.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Navaneetham K, Dharmalingam A. Utilization of maternal health care services in Southern India. J Soc Sci Med. 2002;55:1849–1869. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00313-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.World Health Organization. Quality of care: a process for making strategic choices in health systems. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2006. http://www.who.int/management/quality/assurance/QualityCare_B.Def.pdf?ua=1 Accessed October 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wagle R R, Sabroe S, Nielsen B B. Socioeconomic and physical distance to the maternity hospital as predictors for place of delivery: an observation study from Nepal. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2004;4:8. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-4-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.von Elm E, Altman D G, Egger M et al. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Int J Surg. 2014;12:1495–1499. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2014.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tayler-Smith K, Zachariah R, Manzi M et al. An ambulance referral network improves access to emergency obstetric and neonatal care in a district of rural Burundi with high maternal mortality. Trop Med Int Health. 2013;18:993–1001. doi: 10.1111/tmi.12121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]