Abstract

Extrarenal Wilms' tumor of the ovary is a very rare tumor likely derived from embryonic mesonephros. We present the first reported case of a teratoid extrarenal Wilms' tumor of the ovary with a short review of the existing literature. In the case, a 26-year-old woman presented with back pain and was found to have a dermoid cyst; three years later, she presented again, now pregnant, with severe abdominal pain. She was diagnosed with an immature teratoma consisting of a Wilms' tumor (immature component) arising within a mature teratoma and treated exclusively with surgery and surveillance. The recovery from surgery was uneventful and the patient remains without evidence of disease with eleven months of follow-up.

Keywords: Wilms' tumor of ovary, Immature teratoma

Highlights

-

•

Offered here is an approach to treating rare extrarenal Wilms' tumor in pregnancy.

-

•

Patients can present with vaginal bleeding, abdominal pain, and masses > 9 cm.

-

•

Treatment with surgery alone is reasonable for tumors with favorable histology.

1. Clinical presentation

In March 2014, a 26-year-old female reported back pain, and MRI revealed a 10 cm right ovarian mass and a two-centimeter left ovarian dermoid cyst. She subsequently underwent a laparoscopic right ovarian cystectomy. Gross specimen showed tufts of hair. Final pathology revealed a mature cystic teratoma; no components of immature teratoma were identified. In December 2015, the now twenty-eight-year-old G1P0 female at 11 weeks' gestation presented to an outside hospital. A dating ultrasound was performed, showing a fetus, a 13.8 × 11.1 cm multi-loculated right ovarian cyst with little ovarian tissue, and a 2.6 × 2.4 cm left ovarian dermoid cyst. She remained asymptomatic, reporting no pain or gastrointestinal complaints.

In early January 2016, now at 14 weeks 2 days' gestation, the patient underwent surgery for management of suspected ovarian torsion and rupture. Exploratory laparotomy revealed bilateral adnexal cysts (13 cm on right and 3 cm on left), and she underwent a right oophorectomy. Given concerns for blood loss and difficulty delineating normal ovarian tissue from dermoid cyst on the left, decision was made not to proceed with left-sided oophorectomy. Pathology was reviewed at Emory University and then at Massachusetts General Hospital by an expert in gynecologic pathology, and a diagnosis was made: malignant immature teratoma of right ovary, composed of a small element of Wilms' tumor (immature component) arising within a mature teratoma and associated with a mucinous cystadenoma.

2. Treatment

Since the Wilms' tumor represented a minute component of an otherwise benign dermoid cyst and she was 22 weeks pregnant, chemotherapy was not recommended. Plan was made for close observation with repeat imaging following pregnancy, and consideration of surgical re-exploration if recurrent or grossly enlarging cysts were noted on imaging.

3. Outcome and follow-up

The patient did not receive adjuvant therapy, and she remains without evidence of disease after eleven months of follow-up. In fact, ultrasound imaging eight months following surgery revealed a left ovary with a non-enlarging dermoid cyst (measuring three centimeters, the same left cyst noted at prior surgery). Given stability of cyst size, plan was made to follow the cyst with surveillance ultrasound imaging every 6 months for 12 months, and annually thereafter.

4. Pathology

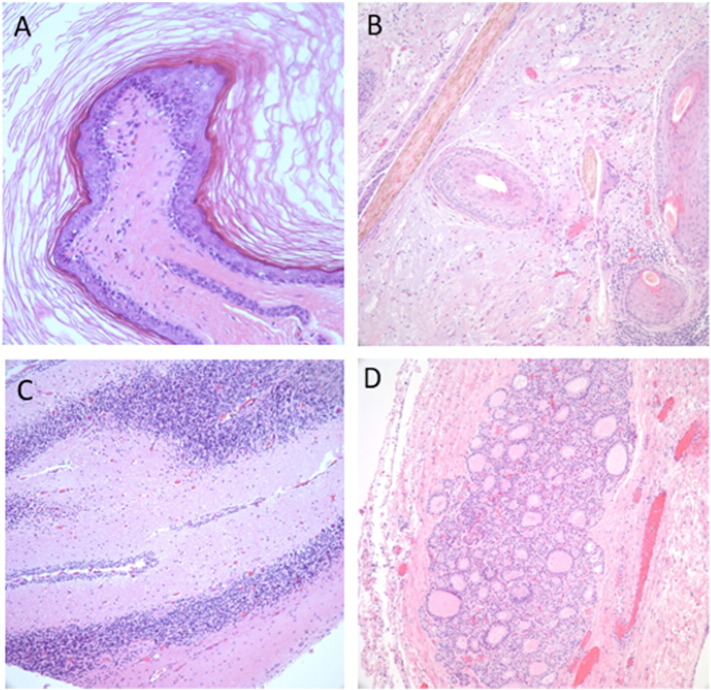

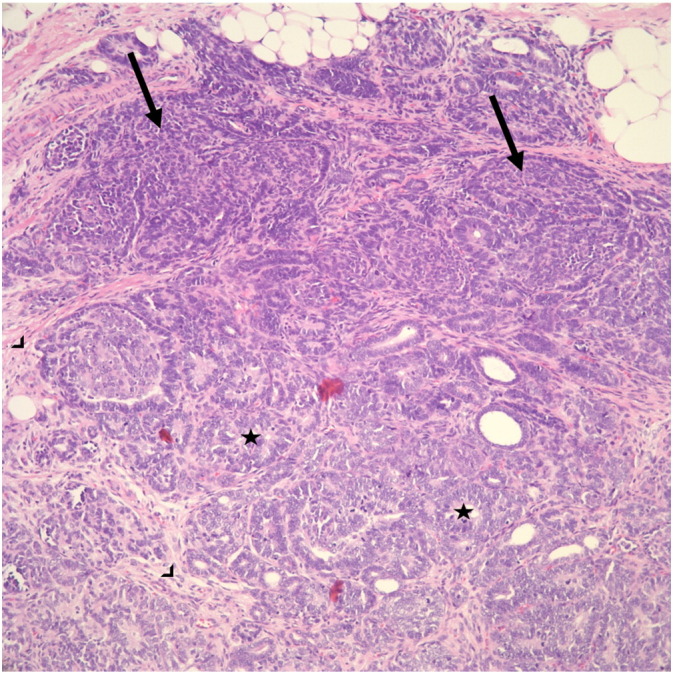

In our case, examined sections of tumor showed mature cystic teratoma (see Fig. 1) and a small one-centimeter focus of Wilms' tumor (see Fig. 2), determined to represent a malignancy within a dermoid cyst. One of the trademark features of ovarian extra-renal Wilms tumor (EWT) is that undifferentiated blastemal tissue with stromal, tubular, and glomeruloid elements characteristic of classic Wilms' Tumor is found within in extra-renal location without evidence of a primary tumor elsewhere (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Mature teratoma. This benign tumor is composed of ectodermal (epidermis), endodermal (respiratory, gastrointestinal, thyroid, etc.), mesodermal (smooth muscle, bone, teeth, cartilage, fat), and neuroectodermal tissue (cerebrum, cerebellum, etc.). Images A and B demonstrate the ectodermal elements including skin and hair, respectively. Cerebellar and thyroid tissue were also identified and are shown in images C and D.

Fig. 2.

Wilms tumor (nephroblastoma). Wilms tumor is a triphasic neoplasm which consists of blastemal (arrow), stromal (arrowhead) and epithelial elements (abortive tubules and glomeruli; star). This tumor is typically positive for WT-1 and negative for CD99.

5. Review of the literature

5.1. Epidemiology and origins

Wilms' Tumor is the commonest malignancy of genitourinary tracts in children, but development of this tumor outside kidneys is rare (Andrews et al., 1992). By definition, diagnosis of EWT excludes a primary tumor in kidneys and has been reported to occur in a variety of locations, including the sacrococcygeal region, adjacent to kidneys, lumbar region, and pelvis (Andrews et al., 1992). For the diagnosis of EWT to apply, it is important that intrarenal tumor and supernumerary kidney be ruled out. In a review of 80 cases of childhood pure EWT (under age 14), female predominance was observed (female to male ratio 3:2) (Shojaeian et al., 2016).

There are two types of EWT: (1) EWTs found as components of teratomas (teratoid WT) and (2) pure EWTs of one tissue type. Teratoid EWT are rarer than pure EWTs. According to Variend et al.'s criteria for diagnosing a teratoid Wilms' tumor, the heterologous elements should comprise > 50% of the tumor in an organoid arrangement (Variend et al., 1984). Many believe embryogenesis of pure EWT parallels that of intrarenal Wilms' tumor, and presence of persistent mesonephric duct remnants in walls of adults' cervix, vagina, ovary, and inguinal regions point to the mesonephros as the origin of the pure EWT (Andrews et al., 1992). Other theories include Connheims' cell rest theory, which holds that cells with persistent embryonic potential will eventually undergo malignant transformation and form pure EWT (Andrews et al., 1992). Similarly, others postulate that teratoid EWT originate directly from misplaced totipotent primitive nephrogenic blastemal elements. In the debate as to whether the origin of any EWT is embryonic or neoplastic, most believe it to be embryonic remains of mesonephric tissue.

5.2. Incidence

To the best of our knowledge, only seven other cases of ovarian EWT have been reported in the literature, and only five other cases of teratoid EWT have been reported (Table 1 shows seven cases of “pure” ovarian EWT; Table 2 shows the five other cases of teratoid EWT). The precise incidence of teratoid EWT or ovarian EWT is uncertain.

Table 1.

Reported cases of WT of the ovary. Summary of the 7 other cases of Wilms' tumor of the ovary presented in the literature.

| First author, year | Age | Presenting symptoms | Treatment | Tumor traits (dimensions) | Presence of anaplasia Presence of teratomatous elements? |

Outcome | Follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nicod (1965) | 35 | Menorrhagia | Exploratory laparotomy + left oophorectomy + radium therapy | 10 cm mass involving left ovary | Not stated Not stated |

No recurrence | 24 months |

| Sahin and Benda (1988) | 56 | b/l calf pain, found to have DVT and pelvic mass | Exploratory laparotomy, total abdominal hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, and appendectomy + external radiation to pelvic and para-aortic area (4640 cGY, 3500 cGy) + 18 courses of vincristine and cyclophosphamide − second look laparotomy showed no residual tumor | 12 cm mass involving left ovary | No No |

No recurrence | 108 months |

| Isaac et al. (2000) | 21 | Menorrhagia, abdominal pain | Exploratory laparotomy, right-salpingo-oophorectomy, wedge resection of contralateral polycystic ovary + bleomycin/etoposide/cisplatin which was changed to actinomycin + vincristine | 19 cm mass involving ovary | No No |

No recurrence | 6 months |

| Pereira et al., 2000 | 3.5 | Abdominal pain and distension | Exploratory laparotomy, right oophorectomy and biopsy of contralateral ovary + vincristine and actinomycin D | 13x10x10 cm mass involving ovary | No No |

No recurrence | 78 months |

| Oner et al. (2002) | 3.5 | Abdominal pain, vomiting | Exploratory laparotomy, excision of mass, left-salpingo-oophorecotmy, appendectomy, and partial omentectomy; bx from: peritoneum, mesentery, retroperitoneal LNs + 4 cycles of chemotherapy (vincristine & actinomycin D) | Firm mass, 13 × 10 × 6.5 cm | No No |

No reported recurrence | 7 months |

| Li et al. (2008) | 22 | Abdominal pain, distension | Exploratory laparotomy + right oophorectomy | 9 × 7 × 5.6 vm | Not stated No |

No reported recurrence | Not reported |

| Marwah et al. (2012) | 1 year 2 months | Abdominal pain, vomiting | Exploratory laparotomy + right salpingo-oophorectomy 4 cycles of chemotherapy (vincristine & actinomycin D) |

Binodular tumor, 10 × 8 cm, extending to ovary (ovary could not be separated), tubes not involved | No No |

No reported recurrence | 3 months |

Table 2.

Reported cases of extrarenal teratoid Wilms' tumor. Summary of the 5 other cases of extrarenal teratoid Wilms' tumor.

| First Author, year | Age in years | Location | Presenting symptoms | Treatment | Tumor traits (dimensions) | Presence of anaplasia? | Outcome | Follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||||||

| Pawel et al. (1998) | 7/M | Partly cystic ureteropelvic mass | 1 week of abdominal pain | Exploratory laparotomy + excision of retroperitoneal mass + vincristine & actinomycin-D × 18 weeks | 8 × 4 cm (spherical) | No | No recurrence | 18 months |

| Song et al. (2010) | 13/F | Partly cystic mass in vagina originating from uterine cervix (no mass in endometrial cavity) | vaginal spotting | Removal of vaginal mass + vincristine, cyclophosphamide, & actinomycin D × 6 months | 6 × 5 cm | No | No recurrence | 84 months |

| Song et al. (2010) | 1 day/F | Multilobulated sacrococcygeal mass | Detected on ultrasound during prenatal care | Excision of mass on Day 2 of life + vincristine & actinomycin-D × 6 months | 15 × 15 cm | No | No recurrence | 29 months |

| Chowhan et al. (2011) | 1.3/M | Retroperitoneal mass below left kidney | Growing abdominal distention | Exploratory laparotomy with excision of mass + vincristine & actinomycin-D × 6 months | 6.6 × 5.9 cm | No | No recurrence | 6 months |

| Baskaran (2012) | 3/M | Right sided solid abdominal mass | Abdominal distention due to mass | Exploratory laparotomy with excision of mass | 10 × 11 cm | No | No recurrence | 12 months |

5.3. Diagnosis, staging, and treatment of ovarian EWT and teratoid EWT

Mean age at time of diagnosis in the reviewed eight cases of ovarian EWT was 21.3 years. Most patients presented with abnormal vaginal bleeding and abdominal pain. In contrast, mean age at diagnosis for the six total cases of teratoid EWT was 9.1 years, and most patients presented with abdominal distention. Diagnosis in all included cases was made on pathologic examination from specimens following surgery. The presented case stands as the only reported case of a teratoid EWT in the ovary in a patient (pregnant or nonpregnant) in the literature.

Ovarian and teratoid Wilms' Tumor behaves as a fast-growing mass characteristic of other embryonal tumors, and in the ovarian EWT cases reviewed, masses were noted to have dimensions 9 cm and larger, and most tumors extensively involved the ipsilateral ovary.

No specific treatment guidelines currently exist for EWT or teratoid EWT, and the guidelines commonly referred to in treatment-planning for EWT may lead physicians to recommend excessively aggressive adjuvant chemotherapy, given many EWT are likely adequately treated with surgery alone. There are also currently no accepted staging criteria for EWT. Staging of extrarenal tumors is challenging, as National Wilms' Tumor Study (NWTS) recommendations would hold that all EWT be considered Stage II or higher, given they exist beyond renal capsules (Shojaeian et al., 2016, Madanat et al., 1978). This staging would mandate chemotherapy for all patients with EWT, despite the fact that most EWT have favorable histology, and long-term tumor-free survival has been documented in cases of EWT treated exclusively with surgery (Shojaeian et al., 2016, Baskaran, 2012).

Treatment of the five other cases of teratoid EWT in the literature consisted of surgery and/or chemotherapy. In treatment of one of the cases of teratoid EWT presenting as a right sided abdominal mass (10 × 11 cm), surgical excision alone yielded promising outcomes (at least one-year of disease-free survival) (Baskaran, 2012).

As noted, in the past, chemotherapy has been recommended for extrarenal Wilms' tumor regardless of size, stage, age at diagnosis, histology, or association with teratoma.

In our literature review, eleven of the twelve other reviewed patients underwent operative excision and adjuvant chemotherapy similar to NWTS. However, given the presented patient was twenty-eight years old and pregnant, had stage II disease because of location alone, and had favorable histology with prominent cystic tissue without anaplasia, conservative treatment with surgery and preservation of fertility was pursued. Furthermore, renal teratoid WT have been less responsive to chemotherapy and radiation (Baskaran, 2012). It thus appears reasonable to approach treatment of teratoid EWT with similar considerations as pure EWT: surgical excision is key with careful inspection of kidneys and peritoneum for tumor implants, and adjuvant chemotherapy according to NWTS protocols may be considered based on histologic grade and stage of tumor. As has been proposed, perhaps the definition of Stage I definition in NWTS should be modified to specify a localized tumor amenable to complete excision with clear margins (Shojaeian et al., 2016).

5.4. Prognosis

Caution should be exercised in interpreting survival data given small numbers of patients. However, it appears from the general trend noted above that prognosis of ovarian EWT and teratoid EWT with favorable histology (i.e. cystic variants, no anaplasia) is similar to that of intrarenal Wilms' Tumor (Narasimharao et al., 1989). From the limited review of six cases of ovarian EWT and four cases of teratoid WT treated with surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy (ten cases), a single case of ovarian EWT treated with surgery and chemoradiation, and two cases of teratoid WT treated with surgery alone (including the presented case), we cannot make statements on differences in disease recurrence and mean recurrence interval. However, authors of a review of 80 cases of childhood EWT suggest radiotherapy be reserved for unresectable tumors or those with gross residual disease, recurrence, or metastasis (Shojaeian et al., 2016). From the now two existing case reports on teratoid EWT, surgical excision alone seems reasonable (Baskaran, 2012).

6. Conclusion

Ovarian Wilms' tumor likely arises from mesonephric tissue in the ovary or associated teratoma, and only eight cases of ovarian EWT and six cases of teratoid EWT (including the presented case) have been reported in the literature. The most common presenting symptoms are abdominal pain and abnormal bleeding

Ovarian Wilms' Tumor is a pathologically complex diagnosis, since nephroblastic elements characteristic of EWT can occur alone or in association with teratomatous elements. Based on the reported outcomes of teratoid EWT at other sites, it appears teratoid ovarian EWT carries a better prognosis than pure EWT.

In this review of extrarenal Wilms' tumor of the ovary and teratoid EWT in general, the recurrence rate was 0%, and median follow-up for ovarian EWT was 15.5 months (median follow-up for teratoid EWT was 18 months). From this review, we advocate that at a minimum, treatment for ovarian EWT should consist of removal of affected ovary with consideration of adjuvant chemotherapy for those with pure EWT based on additional histologic grading factors.

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

References

- Andrews P.E., Kelalis P.P., Haase G.M. Extrarenal Wilms' tumor: results of the National Wilms' Tumor Study. J. Pediatr. Surg. 1992;27(91):1181–1184. doi: 10.1016/0022-3468(92)90782-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baskaran D. Extrarenal teratoid Wilms' tumor in association with horseshoe kidney. Indian J. Surg. 2012;75:128–132. doi: 10.1007/s12262-012-0606-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chowhan A.K. Extrarenal teratoid Wilms' tumour. Singap. Med. J. 2011;52(6):e134–e137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaac M.A. Pure cystic nephroblastoma of the ovary with a review of extrarenal Wilms' tumors. Hum. Pathol. 2000;31:761–764. doi: 10.1053/hupa.2000.7627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L., Zhou X., Zhang H. Adult extrarenal Wilms' tumor of the ovary. Chin. J. Pathol. 2008;37:284–285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madanat F. Extrarenal Wilms tumor. J. Pediatr. 1978;93:439–443. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(78)81153-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marwah N. Extrarenal Wilms' tumor of the ovary: a case report and short review of the literature. J. Gynecol. Surg. 2012;28:306–309. [Google Scholar]

- Narasimharao K.L. Extrarenal Wilm's tumor: a case report. Paediatr. Surg. 1989;24:212–214. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(89)80253-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicod J.L. Tumeur de Wilms dans l'ovaire. Bull. Cancer. 1965;52:173–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oner U. Wilms' tumor of the ovary: a case report. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2002;37:127–129. doi: 10.1053/jpsu.2002.29447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawel B. Teratoid Wilms tumor arising as a botryoid growth within a supernumerary ectopic ureteropelvic structure. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 1998;122:925–928. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira F. Extrarenal Wilms tumor of the left ovary: a case report. J. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 2000;22:88–89. doi: 10.1097/00043426-200001000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahin A., Benda J.A. Primary ovarian Wilms' tumor. Cancer. 1988;61:1460–1463. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19880401)61:7<1460::aid-cncr2820610731>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shojaeian R., Hiradfar M., Sharifabad P.S., Zabolinejad N., van den Hevel-Eibrink M.M. Wilms Tumor. Codon Publications; Brisbane, Australia: 2016. Extrarenal Wilms' tumor: challenges in diagnosis, embryology, treatment, and prognosis; pp. 77–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song J.S. Extrarenal teratoid Wilms' tumor: two cases in unusual locations, one associated with elevated serum AFP. Pathol. Int. 2010;60:35–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.2009.02468.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Variend S., Spicer R.D., Mackinnon A.E. Teratoid Wilms' tumor. Cancer. 1984;53:1936–1942. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19840501)53:9<1936::aid-cncr2820530922>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]