ABSTRACT

Previously, we demonstrated that Bcl-2-like 10 (Bcl2l10) is associated with meiotic spindle assembly and that the gene that is most strongly down-regulated by Bcl2l10 RNAi is targeting protein for Xklp2 (Tpx2). Tpx2 is a well-known cofactor that controls the activity and localization of Aurora kinase A (Aurka) during mitotic spindle assembly. Therefore, this study was conducted (1) to identify the associations among Bcl2l10, Tpx2, and Aurka and (2) to understand how Bcl2l10 regulates meiotic spindle assembly in mouse oocytes. Bcl2l10, Tpx2, and Aurka co-localized on the meiotic spindles, and Bcl2l10 was present in the same complex with Tpx2. Tpx2 and Aurka expression decreased whereas phospho-Aurka increased in Bcl2l10 RNAi-treated oocytes. Counterbalancing changes in the levels of these 2 activators, Tpx2 and phospho-Aurka, resulted in decreased Aurka catalytic activity after Bcl2l10 RNAi treatment. Bcl2l10 RNAi decreased the expression of microtubule organizing center (MTOC)-related proteins, disturbed MTOC formation and disrupted meiotic spindle assembly. Our data demonstrate that Bcl2l10 is a binding partner of Tpx2 and a new regulator of the complex controlling the organization of microtubules and MTOC biogenesis in meiotic spindle assembly. The discovery of Bcl2l10 as a new effector of Aurka suggests that Bcl2l10 may have diverse functions in mitotic cells.

KEYWORDS: Aurka, Bcl2l10, mouse oocyte maturation, MTOC, Tpx2

Introduction

Bcl2l10, also called Diva or Boo, is a member of the Bcl-2 family, which has various functions in regulating apoptotic processes. Bcl-2 family members share 4 conserved regions termed Bcl-2 homology domains BH1 to BH4.1 Pro-apoptotic genes require the BH3 domain to activate apoptosis and to interact with anti-apoptotic genes such as Bcl-2/Bcl-XL.2,3 Structurally, Bcl2l10 is an anti-apoptotic gene because it lacks the BH3 domain.4 However, functionally, Bcl2l10 has been reported to act as both an anti-apoptotic gene and a pro-apoptotic gene.4-7

Bcl2l10 mRNA expression is restricted to the ovary and testis in adult mice.4 In a previous study, we found that Bcl2l10 was highly expressed in mouse oocytes and that Bcl2l10-associated proteins were involved in the cytoskeletal system.8,9 To determine the role of Bcl2l10 during oocyte maturation, we used Bcl2l10 RNAi and found that these oocytes arrested at metaphase I (MI) and presented abnormal spindles and aggregated chromosomes. As a result, we reported the non-apoptotic role of Bcl2l10 in meiotic cell cycle regulation.10 To better understand the regulatory mechanism of Bcl2l10 in oocytes, we conducted microarray analysis to identify downstream changes after Bcl2l10 RNAi. Among the top 20 genes downregulated by Bcl2l10 RNAi, 5 were associated with the cytoskeletal system, which is consistent with the interaction of Bcl2l10 with filaments and tubules.10,11 Notably, Tpx2 was the gene showing the greatest down-regulation in response to Bcl2l10 RNAi.11

In mitotic cells, Tpx2 is a well-known microtubule-binding protein and an effector of Ras-related nuclear protein-GTP (RanGTP).12 Tpx2 is required for RanGTP-dependent microtubule assembly around chromosomes. Active Tpx2 localizes on the microtubule and regulates spindle assembly.13,14 In mouse oocytes, Tpx2 has essential roles in meiotic spindle assembly. Tpx2 depletion in oocytes impaired meiosis I completion and resulted in only a few microtubules and tiny bipolar spindles.15 Interestingly, according to the results reported by Brunet et al., the altered morphologies of oocytes after Tpx2 RNAi treatment were very similar to our results with Bcl2l10 RNAi oocytes.10 In addition, Tpx2 is a well-known cofactor involved in localizing Aurka to the spindle microtubules and directly activating Aurka.12 Tpx2 targets centrosome-bound Aurka, moves onto the spindle microtubules, and directly activates Aurka.16

Aurka is a pivotal kinase that has multiple functions in mitosis. Aurka localizes to centrosomes and spindle poles and is primarily responsible for centrosome maturation and separation for bipolar spindle assembly during mitosis.17,18 In addition, Aurka regulates other important mitotic events, such as the spindle checkpoint, mitotic entry, kinetochore function, cytokinesis, asymmetric cell division, and cell fate determination.19,20 Both the depletion and overexpression of Aurka result in abnormal mitosis and lead to genomic instability, aneuploidy, and tumor formation.21,22

Our microarray analysis indicated that Tpx2 was a major gene showing changes after Bcl2l10 RNAi; therefore, we speculated that Aurka, a functional partner of Tpx2, might also be associated with Bcl2l10. The primary objective of this study was thus to identify the associations among Bcl2l10, Tpx2, and Aurka. By extension, because Tpx2 and Aurka primarily function in mitotic spindle assembly and centrosome maturation, our second objective was to understand how Bcl2l10 regulates meiotic spindle formation in the mouse oocytes. In the present study, we showed that Bcl2l10 is a key factor for MTOC formation during meiotic spindle assembly as a binding partner of Tpx2 and a master regulator of Aurka, an indispensable kinase for cell division.

Results

Bcl2l10 co-localizes with Tpx2, but not with Aurka, on meiotic spindles in oocytes

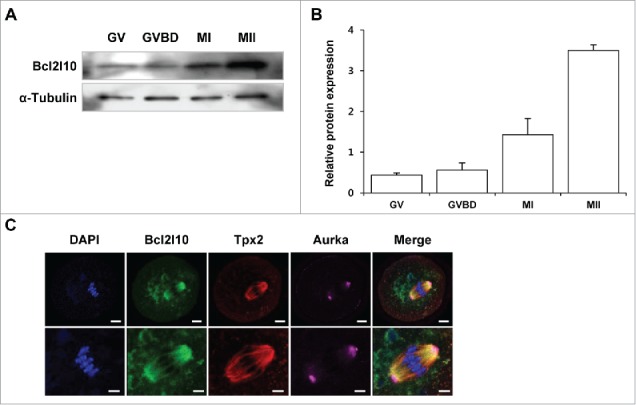

We previously found that Bcl2l10 transcripts and protein were expressed in ovaries, especially in the germinal vesicle (GV) oocytes but not in the follicular cells such as cumulus cells (CCs) and granulosa cells (GCs).10 We further examined Bcl2l10 protein expression during mouse oocyte maturation and found that Bcl2l10 accumulated gradually from GV to metaphase II (MII) during mouse oocyte maturation (Fig. 1A and B). To visualize Bcl2l10, Tpx2, and Aurka on the meiotic spindles, we stained MI oocytes with barrel-shaped spindles with Bcl2l10, Tpx2, and Aurka antibodies simultaneously. As a result, Bcl2l10 and Tpx2 co-localized to the meiotic spindles of the oocytes, but Aurka localized to the spindle poles (Fig. 1C).

Figure 1.

Expression of Bcl2l10 protein during mouse oocyte maturation and localization of Bcl2l10, Tpx2, and Aurka in MI oocytes. (A, B) Western blot analysis of Bcl2l10 protein expression during normal in vitro oocyte maturation. GV, GVBD, MI, and MII oocytes were collected after 0, 2, 8, and 16 h of in vitro culture, respectively. Protein lysates of 200 oocytes were loaded per lane. α-Tubulin was used as a loading control. The experiment was performed 3 times, and the data are presented as the mean ± SEM. (C) Bcl2l10 and Tpx2 co-localized on microtubules, but Aurka localized in the MTOC region in MI oocytes (upper lane). Oocytes were stained with Bcl2l10-, Tpx2- and Aurka-specific primary antibodies simultaneously (from left to right). DNA was counterstained with DAPI (blue channel). Bcl2l10 (FITC, green channel), Tpx2 (Rhodamine, red channel), Aurka (Alexa 647, pink channel), and merged images. Bar=10 µm. (Lower lane) Higher-magnification photographs of the corresponding image are shown below. Bar=5 µm.

We investigated the localization of Bcl2l10, Tpx2, and Aurka in different maturation stages of oocytes from GV to MII (Fig. S1). In GV oocytes, Bcl2l10 was distributed throughout the cytoplasm and expressed weakly in the nuclear membrane. At the germinal vesicle break down (GVBD) stage, during microtubule formation and chromatin condensation, Bcl2l10 localized on the microtubules around the chromatin structure. At MI and MII stages, Bcl2l10 was primarily detected on the meiotic spindle, including the spindle pole regions (Fig. S1A).

Tpx2 appeared to be localized in MTOCs in the GVBD oocytes and on the spindle microtubule when the bipolar spindles formed in the MI oocytes.15 Interestingly, Bcl2l10 and Tpx2 co-localized on the bipolar spindles in MI and MII oocytes (Fig. S1B). Meanwhile, Aurka clearly accumulated as a single dot in the nucleus in GV oocytes and distributed into puncta around the chromosomes when GVBD occurred. At MI and MII stages, similar to Bcl2l10 and Tpx2, Aurka localized on the microtubules but was primarily observed in the spindle poles (Fig. S1C).

Phosphorylation at the threonine 288 position in the activation loop of Aurka (T288-Aurka) is requisite for its catalytic activation.23 According to a previous observation, T288-Aurka localizes primarily in the centrosomes of mitotic cells24 and in MTOCs during mouse oocyte maturation.25 We also observed co-localization of T288-Aurka and Pericentrin, a MTOC marker,25 during oocyte maturation, indicating that T288-Aurka localizes to MTOCs in MII oocytes (Fig. S1D).

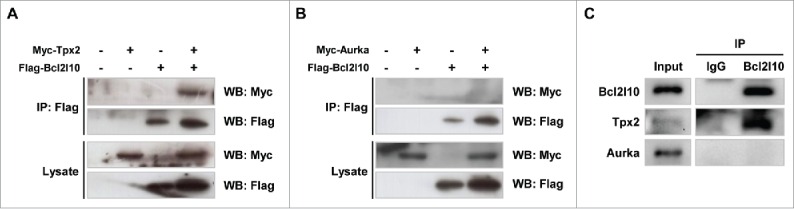

Bcl2l10 interacts with Tpx2 but not with Aurka

The co-localization of Bcl2l10, Tpx2, and Aurka implies that these 3 factors have functional interactions on the spindle microtubule. Thus, we examined their novel protein-protein interactions by co-immunoprecipitation using HEK293T cells. When Flag-Bcl2l10 and Myc-Tpx2 plasmid constructs were co-transfected and Flag-Bcl2l10 was precipitated with anti-Flag antibody, Myc-Tpx2 co-precipitated (Fig. 2A). However, when Flag-Bcl2l10 and Myc-Aurka plasmid constructs were co-transfected, Myc-Aurka did not co-precipitate (Fig. 2B). Additionally, to investigate the endogenous interaction of Bcl2l10 with Tpx2 and Aurka in mouse oocytes, a protein lysate of mouse MII oocytes (n=1000) was immunoprecipitated with a Bcl2l10 antibody, and the precipitate was reacted with Tpx2 and an Aurka antibody. Only Tpx2 was co-immunoprecipitated by Bcl2l10 (Fig. 2C). These results strongly suggest that Bcl2l10 formed a complex with Tpx2 but did not bind to Aurka within mouse oocytes.

Figure 2.

Bcl2l10 is a binding partner of Tpx2 but not Aurka. (A, B) Co-immunoprecipitation assays were performed using lysates from HEK293T cells that were co-transfected with the indicated plasmid constructs. Cell lysates were precipitated with an anti-Flag antibody and blotted with either an anti-Myc or anti-Flag antibody, as indicated. (A) Flag-Bcl2l10 and Myc-Tpx2 plasmids were co-transfected into HEK293T cells. (B) Flag-Bcl2l10 and Myc-Aurka plasmids were co-transfected into HEK293T cells. (C) Bcl2l10 forms a complex with Tpx2 in mouse oocytes. Lysates from 150 MII oocytes were used as the input (lane 1). Protein extracts from 1,000 MII oocytes were immunoprecipitated with goat IgG (lane 2) or a Bcl2l10 antibody (lane 3) and reacted with Tpx2 and Aurka antibodies.

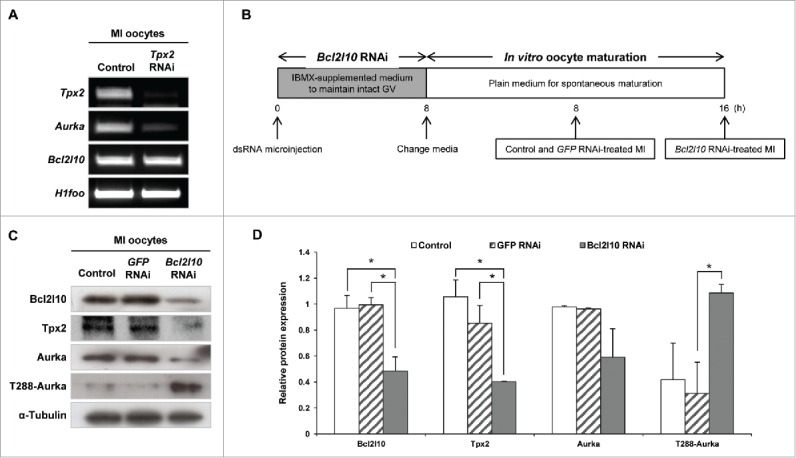

Decreased Tpx2 and Aurka along with increased phosphorylation of Aurka ultimately reduces Aurka activity

As noted above, Tpx2 was the gene that was down-regulated to the greatest extent by Bcl2l10 RNAi, and we predicted that Aurka exerts its function under the effect of Bcl2l10 due to the association between Tpx2 and Aurka.11 However, because the relationship between Tpx2 and Aurka has not yet been described in mouse oocytes, we first examined whether Tpx2 regulates Aurka expression during oocyte maturation through a Tpx2 RNAi experiment. Tpx2 RNAi-treated oocytes arrested in the MI stage, as previously reported,15 and showed decreased Aurka expression, indicating a role for Tpx2 in regulating the expression of Aurka in mouse oocytes (Fig. 3A). In addition, the unaltered expression of Bcl2l10 in Tpx2 RNAi-treated oocytes again suggested that Tpx2 is under the regulation of Bcl2l10, but not vice versa (Fig. 3A). Fig. 3B depicts the experimental strategy that we used for Bcl2l10 RNAi. We confirmed the downregulation of Tpx2 and Aurka mRNA and protein after Bcl2l10 RNAi treatment (Fig. S2) and observed unexpected up-regulation of T288-Aurka (Fig. 3C and D).

Figure 3.

Bcl2l10 regulates the expression of Tpx2, Aurka, and phosphorylated Aurka. (A) Tpx2 RNAi treatment resulted in specific suppression of Tpx2 mRNA expression. In addition, Aurka mRNA was decreased by Tpx2 RNAi. Oocyte-specific H1foo was used as an internal control. (B) Experimental design for Bcl2l10 RNAi experiment. After oocytes were microinjected with Bcl2l10 dsRNA, intact GV oocytes were incubated for 8 h in IBMX-supplemented M16 medium for Bcl2l10 degradation followed by further culture for 16 h in plain M16 medium for in vitro oocyte maturation. Because Bcl2l10 RNAi oocytes were arrested at the MI stage, oocytes of each group were collected at the indicated time points for MI and used for Western blot analysis. (C, D) Tpx2 and Aurka protein expression decreased, whereas T288-Aurka increased after Bcl2l10 RNAi treatment. The lysate of 200 oocytes was loaded in each lane. α-Tubulin was used as a loading control. The experiment was performed 3 times, and the data are presented as the mean ± SEM. Asterisks indicate statistical significance at p < 0.05. Control: non-injected MI oocytes; GFP RNAi: normal MI oocytes after GFP RNAi was used as non-targeting control for RNAi experiments; Bcl2l10 RNAi: MI-arrested oocytes after Bcl2l10 RNAi treatment.

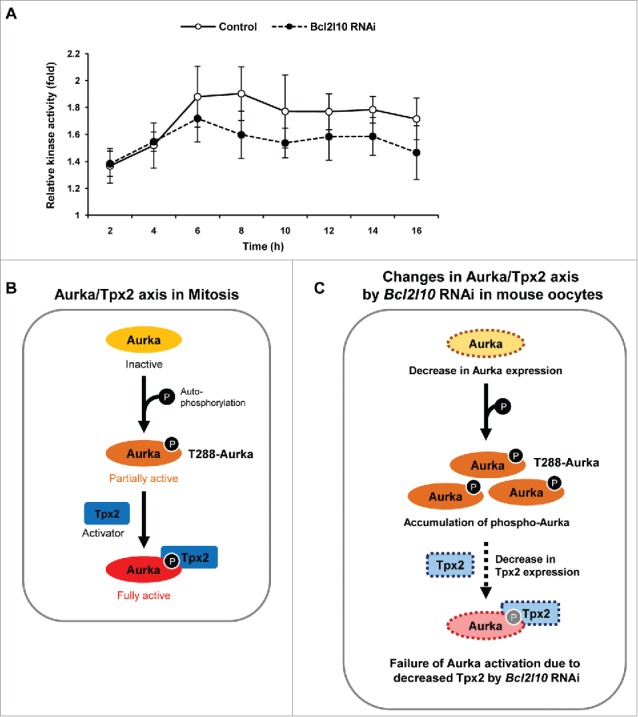

Both the auto-phosphorylation of Aurka and binding to the activator Tpx2 are essential features for the complete catalytic activation of Aurka.26 Interestingly, we found contrasting results, which are shown in Fig. 3C; Bcl2l10 RNAi decreased Tpx2 expression and increased phosphorylated T288-Aurka in oocytes. Thus, we decided to evaluate Aurka activity and found that it tended to decrease after Bcl2l10 RNAi compared with control oocytes (Fig. 4A). Based on the Aurka/Tpx2 axis in mitotic cells, the depletion of Bcl2l10 in mouse oocytes has broad effects on the expression and auto-phosphorylation of Aurka and on Tpx2 expression (Fig. 4B and C). Finally, we concluded that the decreased expression of Tpx2 caused by Bcl2l10 RNAi reduced Aurka activity in spite of the increased Aurka auto-phosphorylation (Fig. 4C).

Figure 4.

Bcl2l10 RNAi reduces the catalytic activity of Aurka. (A) Aurka activity was assessed by measuring the phosphorylation of Histone H3, an Aurka substrate. Oocytes were collected every 2 h during in vitro maturation. Kinase activity was determined by quantifying the phosphorylation of substrates relative to that of control oocytes at 0 h. The Y-axis depicts the fold changes (log scale) and the X-axis depicts the time points at which oocytes were sampled during oocyte in vitro maturation. Five oocytes were used per time point. Error bars represent SD (B) Schematic diagram for the molecular mechanism of Aurka activation known in mitosis. First, Aurka was partially activated by phosphorylation at threonine 288 in its activation loop. Second, partially activated T288-Aurka was fully activated by the binding of the activator protein Tpx2. Binding with Tpx2 protects phosphorylated Aurka from dephosphorylation by protein phosphatase 1. (C) Schematic diagram depicting the speculated roles of Bcl2l10 in the Aurka/Tpx2 axis in the mouse oocytes based on the results of Bcl2l10 RNAi treatment in the present study. When Bcl2l10 was absent, Aurka and Tpx2 expression decreased, whereas the amount of T288-Aurka [auto-phosphorylated Aurka] increased. We propose that Aurka activity decreased because partially active T288-Aurka could not be fully activated due to decreased Tpx2. Therefore, we concluded that the down-regulation of Tpx2 is a decisive factor for the full activation of Aurka.

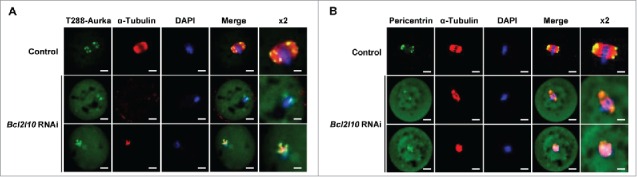

Bcl2l10 RNAi disturbed MTOC formation in oocytes

The MTOC distribution was observed via immunofluorescence staining with T288-Aurka and Pericentrin after the Bcl2l10 RNAi treatment of oocytes. Because the auto-phosphorylation of Aurka occurred in the MTOCs of mouse oocytes,25,27 we co-stained T288-Aurka and Pericentrin. T288-Aurka was not concentrated at the MTOC as indicated by Pericentrin but was dispersed in the cytoplasm of the MI-arrested oocytes after Bcl2l10 RNAi (Fig. 5A and B). These results strongly suggest that Bcl2l10 is a regulator of MTOC formation in mouse oocytes.

Figure 5.

Bcl2l10 RNAi disturbs MTOC formation in oocytes. Changes in MTOC formation after Bcl2l10 RNAi were determined by immunofluorescence staining. MI-arrested oocytes after Bcl2l10 RNAi were collected and stained with (A) T288-Aurka (n=7; Alexa 488, green channel), and (B) Pericentrin (n=13; Alexa 488, green channel). The spindle (Alexa 594, red channel) was stained with antibody directed against α-Tubulin. Pericentrin was used as an MTOC marker. DNA (blue channel) was counterstained with DAPI. Bar=10 µm. (lane 5) Higher-magnification photographs of the corresponding image are shown. Bar=5 µm.

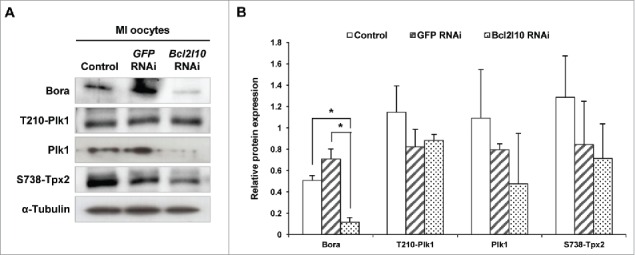

Bcl2l10 RNAi reduces MTOC-associated protein expression

In mouse oocytes, many proteins in addition to Aurka are required for MTOC formation. For example, Polo-like kinase 1 (Plk1) is activated on MTOCs and is required for the localization of other centrosomal proteins to MTOCs.28 In addition, Bora, known as a binding partner of Aurka, regulates the precise localization of Aurka and Plk1.29 The protein expression of Bora was significantly reduced, and the levels of Plk1, phosphorylated Tpx2 also showed a decreasing tendency following Bcl2l10 RNAi (Fig. 6A and B). However, we observed no change in Plk1 phosphorylated at Threonine 210 (T210-Plk1). Therefore, we concluded that Bcl2l10 is involved in controlling MTOC formation by regulating the expression and recruitment of many other important protein components related to MTOC formation.

Figure 6.

Bcl2l10 RNAi affected the expression of MTOC-associated proteins. The expression levels of Bora and Plk1 and the phosphorylation of T210-Plk1 and S738-Tpx2 decreased after Bcl2l10 RNAi treatment. The lysate of 200 oocytes was loaded in each lane. α-Tubulin was used as a loading control. The experiment was performed 3 times, and the data are presented as the mean ± SEM. Asterisks indicate statistical significance at p < 0.05. Control: non-injected MI oocytes; GFP RNAi: normal MI oocytes after GFP RNAi was used as non-targeting control for RNAi experiments; Bcl2l10 RNAi: MI-arrested oocytes after Bcl2l10 RNAi.

Discussion

In previous studies, we demonstrated that Bcl2l10 has non-apoptotic functions as a cytoskeletal regulator of the meiotic processes in oocytes.10 Those findings were intriguing because Bcl2l10 has generally been considered an apoptotic gene that interacts with many other Bcl-2 family members. Our previous findings that Bcl2l10 RNAi led to changes in the expression of many cytoskeletal proteins, including Tpx2, a protein essential for microtubule assembly, suggested a molecular function of Bcl2l10 in meiotic spindle assembly.11

Bcl2l10 is a binding partner of Tpx2 on meiotic spindle microtubules

Accordingly, our first task was to reveal the molecular interaction between Bcl2l10 and Tpx2. Based on microarray results, the reduction of Tpx2 expression in Bcl2l10 RNAi-treated mouse oocytes was a predictable outcome. However, the co-localization and protein-protein interaction of Bcl2l10 and Tpx2 in microtubules were interesting findings that suggest a functional correlation between Bcl2l10 and Tpx2 in the meiotic spindle assembly. The positioning of Tpx2 on microtubules is regulated by an intracellular Ran-GTP gradient.30 Before the mitotic spindle forms, Tpx2 activity is inhibited by Importin-α and Importin-β binding in the cytoplasm. When the Importin-Tpx2 interaction is disassembled by the high RanGTP gradient formed near the chromosomes, Tpx2 is activated and localized on microtubules.30 Similarly, RanGTP is needed for spindle assembly and extrusion of the first polar body.31 Because Bcl2l10 co-localized with Tpx2 in microtubules during oocyte maturation, Bcl2l10 may also regulate meiotic spindle assembly via a RanGTP-dependent mechanism, but this possibility requires further examination.

Bcl2l10 is a new functional regulator of Aurka in oocyte meiosis

Centrosomal protein of 192 kDa (Cep192), another Aurka co-factor, was also one of the top 20 genes downregulated by Bcl2l10 RNAi.11 Unlike Tpx2, which localizes in microtubules, Cep192 is a centrosome-specific scaffold for Aurka that directly activates Aurka on the centrosomes.32,33 As we expected, Cep192 protein expression decreased after Bcl2l10 depletion (Fig. S3A). These results provided additional clues that Bcl2l10 regulates Aurka activity in the meiotic cell cycle of the oocytes.

Because the altered expression of Bcl2l10 in turn altered the expression of 2 important Aurka activators, Tpx2 and Cep192, our second task was to identify the association of Bcl2l10 with Aurka. Although Bcl2l10 did not directly interact with Aurka in the co-immunoprecipitation assay, we confirmed that Bcl2l10 is a master regulator with comprehensive effects on Aurka protein expression, auto-phosphorylation, and activity in oocytes. Aurka protein levels decreased following Tpx2 siRNA treatment because Tpx2 protects Aurka from proteasomal degradation during mitosis.34 However, the restoration of Tpx2 levels in Bcl2l10-silenced oocytes did not rescue the low expression of Aurka (data not shown), indicating that Bcl2l10 has substantial influence compared to Tpx2 on the regulation of Aurka protein expression in the oocytes.

Unfortunately, in this study, we could not explain how Bcl2l10 regulates the transcription of Tpx2 and Aurka. Because Bcl2l10 is not a transcription factor, it likely exerts its effects via the non-transcriptional regulation of Tpx2 and Aurka genes. Although we anticipate that Bcl2l10 may act on the stability of the corresponding mRNAs or interact with proteins involved in specific RNA stability, further studies are necessary to determine the mechanism by which Bc2l10 regulates Tpx2 and Aurka expression.

Similar to other protein kinases, Aurka requires phosphorylation on its activation loop (autophosphorylation) and the presence of activator proteins such as Tpx2 for catalytic activity (Fig. 4B).26 These 2 steps occur independently but act synergistically. In this context, Bcl2l10 RNAi-treated oocytes produced contradictory results in the present study. Specifically, T288 phosphorylation, a primary factor for Aurka activation, increased, whereas the level of the activator protein Tpx2 decreased. Ultimately, these counteracting results of Bcl2l10 RNAi led to reduced catalytic activity of Aurka. Auto-phosphorylation partially activates Aurka; phosphorylated Aurka makes a 2-fold greater energetic contribution compared to unphosphorylated Aurka.26 In contrast, Aurka can be dephosphorylated by protein phosphatase 1.35 The binding of the activator protein Tpx2 triggers conformational changes that protect Aurka from dephosphorylation by protein phosphatase 1.26 Thus, Tpx2 is a decisive factor for maintaining the catalytic activity of Aurka. In particular, the binding of Tpx2 alone to unphosphorylated Aurka is sufficient to increase kinase activity approximately 15-fold.26 Accordingly, although we could not determine the mechanism by which Aurka activity was decreased by Bcl2l10 RNAi in this study, we consider decreased Tpx2 protein expression to be a significant factor in the regulation of Aurka activity.

Bcl2l10 controls meiotic spindle assembly by regulating MTOC components

Massive destruction of the numerous maternal factors occurs during oocyte maturation, and the substantial reduction of these factors is required for oocytes to become fertilized and mediate zygotic gene activation after paternal genome integration.36,37 As shown in Fig. 1A, Bcl2l10 protein levels remained higher in MI and MII oocytes, suggesting that Bcl2l10 may be an important factor in processes that regulate meiotic cell cycle completion, such as meiotic spindle assembly. Additionally, it has been reported that Aurka is a critical regulator of spindle assembly and MTOC biogenesis in mouse oocytes.25,27,38,39 Aurka localized in the cytoplasm of GV oocytes and accumulated on the spindle poles in MI and MII oocytes; another report had similar findings (Fig. S1C).39 Aurka RNAi or Aurka inhibitor treatment resulted in MI arrest in oocytes with abnormal spindle structures.25,27

Because we found that Bcl2l10 is a master regulatory gene for Aurka, our final task was to observe any changes in MTOC formation after Bcl2l10 RNAi treatment. Using Pericentrin as an MTOC marker, we showed that MTOC formation during oocyte maturation was abolished by Bcl2l10 RNAi. Recently, Cep192 was shown to co-localize with Pericentrin in mouse oocytes and was used as a marker for MTOCs.40 We also observed normal Cep192 localization in MTOC regions (Fig. S3B) and an abnormal distribution of Cep192 after Bcl2l10 RNAi (Fig. S3C). This result provided additional evidence for the regulatory function of Bcl2l10 in MTOC formation in oocytes.

Furthermore, MTOC-associated proteins including Bora, Plk1 and phosphorylated Tpx2 were all decreased by Bcl2l10 RNAi (Fig. 6). During G2 phase in mitotic cells, the Aurka/Bora complex phosphorylates Plk1 at threonine 210 (T210).41 During mitosis, Tpx2 directly activates Aurka for spindle assembly and maintains the phosphorylation of Plk1.42 Additionally, the phosphorylation of Plk1 increases the ability of Tpx2 to activate Aurka.43 Even though co-factors of Plk1, such as Aurka, Bora and Tpx2, showed decreased expression levels following Bcl2l10 RNAi, the phosphorylation of Plk1 did not change. We expected to identify a new protein that phosphorylates Plk1 and maintains Plk1 phosphorylation in Bcl2l10 RNAi-treated oocytes. Although the expression patterns and functions of these genes in oocyte meiosis were in many ways unlike those in mitosis,15,29,39,44 it could be concluded that Bcl2l10 is strongly engaged as a part of the cascade of the Bora-Plk1-Tpx2-Aurka pathway for regulating meiosis.

Significance of Bcl2l10 as a new regulator of Aurka

The major finding of this study was the identification of Bcl2l10 as a new functional partner of Tpx2 and, consequently, as a regulator of Aurka during meiosis in mouse oocytes. Previously, we showed that Bcl2l10 mRNA and protein expression were significantly higher in mouse ovaries compared to other tissues. In particular, Bcl2l10 was dominantly expressed in oocytes but not in follicular somatic cells, such as CCs and GCs in the ovaries.10 These findings prompted us to raise the following intriguing question: why is Bcl2l10 expression only required for the meiosis of oocytes? A functional connection between Bcl2l10 and Aurka in MTOC formation and Aurka overexpression in cancer cells could be the answer to this intriguing question.

As previously explained, the main roles of Aurka in mitosis are spindle assembly and centrosome maturation. In this regard, Aurka overexpression in proliferating cancer cells showed abnormal centrosome amplification, centrosome number, and aneuploidy.45,46 Interestingly, oocytes have been reported to share common characteristics with cancer cells, and meiosis-specific proteins that are restrictively expressed in ovaries or testis have long been observed in cancer cells.47,48 Oocytes, similar to cancer cells, show a certain degree of aneuploidy when they are unable to sort and cluster MTOCs.48 Therefore, we presumed that Bcl2l10 plays an important role in controlling the rate of aneuploidy by regulating MTOC clustering in the oocytes. In addition, we hypothesized that Bcl2l10 would function cooperatively with Aurka in cancer cells, and as we expected, Bcl2l10 was expressed in various cancer tissues, indicating that Bcl2l10 might be a crucial factor in tumorigenesis (unpublished data). Consequently, the roles of Bcl2l10 and the molecular association between Bcl2l10 and Aurka in cancer cells as well as in oocytes must be investigated carefully.

In conclusion, we report here for the first time that Bcl2l10 forms a protein-protein complex with Tpx2 and regulates meiotic spindle assembly through functional cooperation with Aurka. Bcl2l10 is a master regulatory gene that has far-reaching effects on the regulation of mRNA and protein expression, the auto-phosphorylation, and the kinase activity of Aurka in mouse oocytes. In addition, Bcl2l10 is a crucial factor for MTOC recruitment in mouse oocytes.

Materials and methods

Animals

C57BL/6 mice were obtained from Koatech (Pyeoungtack, Korea) and maintained at the breeding facility at the CHA Bio Complex of CHA University (Pankyo, Korea). All procedures described in this study were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of CHA University and performed in accordance with the Guiding Principles for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Oocyte collection and in vitro maturation

For GV oocyte collection from preovulatory follicles, 4-week-old female C57BL/6 mice were injected with 5 IU pregnant mare serum gonadotropin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and sacrificed 44-46 h later. Cumulus-enclosed oocyte complexes were recovered from ovaries by puncturing the preovulatory follicles with needles. Oocytes were maintained at the GV stage with M2 medium (Sigma-Aldrich) supplemented with 0.2 mM IBMX (Sigma-Aldrich). For in vitro oocyte maturation, GV-arrested oocytes were repeatedly washed in M16 medium without IBMX and then incubated in M16 medium (Sigma-Aldrich) at 37°C with 5% CO2. To collect GVBD, MI, and MII oocytes, the oocytes were matured in vitro for 2, 8, and 16 h, respectively.

dsRNA synthesis was performed to amplify a region of Bcl2l10 cDNA using primers previously reported.10 The Bcl2l10 cDNA fragment was cloned into a pGEM T-easy vector (Promega, Madison, WI, USA), and RNA was synthesized using T7 polymerase and the MEGAscript kit (Ambion, Austin, TX, USA). Equimolar quantities of single-stranded sense and antisense transcripts were mixed, incubated in a single tube at 75°C for 5 min, and then cooled to RT for 3 h. To avoid the presence of contaminant single-stranded complementary RNA in the dsRNA samples, the samples were treated with 1 µg/ml RNase A (Ambion) for 1 h at 37°C. The dsRNA was then subjected to a phenol-chloroform extraction, and the formation of dsRNA was confirmed by gel electrophoresis. GFP dsRNA that was the same size as Bcl2l10 was synthesized as a sham control. For microinjection, dsRNA was diluted to a final concentration of 3.0 µg/μl. Approximately 10 pl of dsRNA was microinjected into the cytoplasm of each GV oocyte in M2 medium containing 0.2 mM IBMX using a constant flow system (FemtoJet; Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany). After the dsRNA was microinjected into the oocytes, the oocytes were incubated in IBMX-supplemented M16 medium for 8 h to allow the sufficient degradation of Bcl2l10 mRNA and were then cultured in plain M16 medium for oocyte maturation.

mRNA extraction and RT-PCR

Oocyte mRNAs were isolated using the Dynabeads mRNA DIRECT Kit (Invitrogen Dynal AS, Oslo, Norway) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, the oocytes were resuspended with lysis/binding buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl, 500 mM LiCl, 10 mM EDTA, 10% LiDS (SDS), and 5 mM DTT) and mixed with pre-washed Dynabeads oligo dT25. After RNA binding, the beads were washed twice with buffer A, followed by buffer B, and RNA was eluted with Tris-HCl (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5). The isolated mRNA was employed as a template for reverse transcription using oligo dT25 primers, according to the MMLV protocol. PCR was performed with a single-oocyte-equivalent amount of cDNA and primers (Table 1). The PCR products were separated in 2% agarose gels.

Table 1.

Primer sequences used for RT-PCR and conditions.

| Genes | Accession numbers | Sequences*(5’ → 3’) | AT (°C) | Size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bcl2l10 | AF067660 | F: CTGATTCAGGCTTTTCTGTC | 60 | 296 |

| R: CGTTTTCTGAAGTTCTCTGG | ||||

| Aurka | NM_011497.4 | F: AGTTGGCAAACGCTCTGTCT | 60 | 160 |

| R: GTGCCACACATTGTGGTTCT | ||||

| Tpx2 | NM_001141977.1 | F: AGCTGGAGGAAGAGCAGAAG | 60 | 130 |

| R: GAACCAGAAGGGTTCTCAGC | ||||

| H1foo | NM_138311 | F: TCCAACACAAGTACCCGACA | 60 | 173 |

| R: GCACAGGCTTTCTTTGTCT |

F and R in the primer codes indicate forward and reverse.

Western blot analysis

For Western blot analysis, protein extracts from 200 oocytes were subjected to 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA). The membranes were incubated for 1 h in TBS containing 5% skim milk as a blocking agent at room temperature (RT). The blocked membranes were then incubated overnight at 4°C with the primary antibodies in TBS-T containing 5% skim milk. The following primary antibodies were used: goat polyclonal anti-Bcl2l10 antibody (SC-8739, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, CA, USA; 1:1000), rabbit polyclonal anti-Tpx2 antibody (NB500-179, Novus Biologicals, Littleton, CO, USA; 1:1000), rabbit monoclonal anti-Aurka antibody (4718, Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA, USA; 1:500), rabbit polyclonal anti-T288-Aurka antibody (3079, Cell Signaling; 1:500), rabbit polyclonal anti-Bora (SC-134938, Santa Cruz Biotechnology; 1:200), rabbit polyclonal anti-pS738-Tpx2 (07-1248, Millipore; 1:500), mouse monoclonal anti-T210-Plk1 (ab39068, Abcam; 1:500), rabbit polyclonal anti-Plk1 (ab47867, Abcam; 1:500), and rabbit polyclonal anti-α-Tubulin (2144, Cell Signaling; 1:1000). After incubation, the membranes were incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies for 1 h at RT. The blot was visualized using the Amersham ECL Prime Western Blotting Detection Reagent (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, Buckinghamshire, UK).

Immunofluorescence staining and image acquisition

Oocytes were fixed in PFA solution (4% PFA and 0.2% Triton X-100) for 40 min at RT, washed 3 times in 0.1% polyvinyl alcohol (PVA)-PBS for 10 min, and then stored overnight in 1% BSA-supplemented 0.1% PVA-PBS (BSA-PVA-PBS) at 4°C. The oocytes were blocked with 3% BSA-PVA-PBS for 1 h and then incubated in 1% BSA-PVA-PBS containing a goat polyclonal anti-Bcl2l10 antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology; 1:20), a rabbit polyclonal anti-T288-Aurka antibody (Cell Signaling; 1:50), a rabbit polyclonal anti-Pericentrin antibody (Covance, Richmond, CA, USA; 1:50) and a mouse monoclonal anti-α-Tubulin antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology; 1:100) at 4°C overnight. After the oocytes were washed 3 times in 1% BSA-PVA-PBS, they were incubated for 1 h at RT with Alexa Fluor 488- or 555-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG or goat anti-mouse IgG (Invitrogen) diluted 1:100 in 1% BSA-PVA-PBS. After the oocytes were washed 3 times in 0.1% PVA-PBS, they were incubated in a DAPI solution (1 mg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich) for 20 min to counterstain the DNA and then mounted between a microscope slide and a clean coverslip. Confocal images were obtained using a Zeiss LMS880 laser scanning microscope (Carl Zeiss, Germany) equipped with an EC Plan Neofluar 20x/0.50 M27 objective (Carl Zeiss). The image acquisition parameters were as follows: for green fluorescence, excitation at 488 nm and emission at 519 nm; for red fluorescence, excitation at 555 nm and emission at 575 nm; and for DAPI, excitation at 358 nm and emission at 461 nm.

Plasmid preparation

The cDNA of full-length mouse Bcl2l10 was amplified by RT-PCR with forward and reverse primers containing BamHI and XhoI sites, respectively. The cDNA of Tpx2 was similarly amplified using forward and reverse primers containing SacII and HindIII sites, respectively. The following sequences were used: Bcl2l10 forward primer, 5’-CGCGGATCCGCCACCATGGCCGACTCGCAG-3’; Bcl2l10 reverse primer, 5’-CCGCTCGAGTAAACGTTTCCAGAT-3’; Tpx2 forward primer, 5’-TCCCCGCGGGGAATGTCACAAGTCCCT-3’; and Tpx2 reverse primer, 5’-CCCAAGCTTGGGCTGGAA CCGAGTGGA-3’. The PCR products of Bcl2l10 and Tpx2 were cloned into the BamHI- and XhoI-digested pCMV-Tag4 vector containing a Flag tag and into the SacII- and HindIII-digested pCMV-Tag5 vector containing a c-Myc Tag, respectively. All plasmids were validated by DNA sequencing.

Cell culture and transfection

Human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293T cells were grown in DMEM (Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA) supplemented with 10% FBS (Gibco) and 100 μg/ml penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco). The day before transfection, the cells were plated in 100-cm plates and maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS without penicillin/streptomycin. The cells were transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). The total amount of transfected plasmid was 10 μg at a ratio of Lipofectamine 2000:DNA of 2.5:1 diluted in OPTI-MEM (Gibco) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The mock control group was treated with only Lipofectamine 2000. Flag-tagged full-length mouse Bcl2l10 (Flag-Bcl2l10) and Myc-tagged full-length mouse Tpx2 (Myc-Tpx2) plasmid constructs were transiently co-transfected into HEK293T cells.

Co-immunoprecipitation assay

Cells were lysed in NP40 lysis buffer (Invitrogen) supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA). In total, 1 mg of extract was incubated with 1 µg of Flag tag-specific antibody (Sigma-Aldrich) overnight at 4°C. Then, 30 µl of protein G Sepharose (Amersham Bioscience) was added and incubated for 4 h at 4°C. Immunoprecipitates were collected by centrifugation at 1,000 g for 5 min at 4°C. After the beads were washed 5 times in NP40 lysis buffer, they were resuspended in 30 µl of 2X SDS sample buffer and boiled for 5 min at 95°C. Samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE.

For co-immunoprecipitation from mouse oocytes, proteins from 1,000 oocytes were incubated with 2 µg of a goat polyclonal anti-Bcl2l10 antibody (SC-8739, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) or normal goat IgG (SC-2028, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) for 16 h at 4°C, followed by incubation with 30 µl of Protein G Sepharose 4 Fast Flow (GE Healthcare) for 1 h at 4°C. The beads were then washed 3 times with NP40 lysis buffer and boiled in 20 µl of SDS-PAGE sample buffer, and the immunoprecipitates were analyzed via Western blotting.

Aurka activity assay

At each 2-h interval of in vitro culture, oocytes were washed in 0.1% PVA-PBS, and then 5 oocytes in 1 µl of 0.1% PVA-PBS were lysed with 4 µl of RIPA buffer. Samples were frozen at -80°C until assayed. After the oocytes were thawed, they were added to 5 µl of kinase buffer containing 0.3 µCi/μl [γ-32P]-ATP (250 μCi/25 µl; Amersham Bioscience, Piscataway, NJ, USA) and 5 μl of Histone H3 (5 mg/ml) as a substrate solution and incubated for 20 min at 37°C. The reaction was terminated by adding 5 µl of 4X SDS sample buffer and boiling for 5 min. Samples were separated by 15% PAGE, dried for 1 h, and then stored at -80°C for 72 h. Labeled Histone H3 was analyzed by autoradiography. Kinase activity was quantified by measuring the area of each lane using Image J (National Institute of Health, Bethesda, Maryland, USA). The values are presented as a ratio relative to control oocytes at 2 h.

Statistical analysis

Data were derived from at least 3 separate and independent experiments and are presented as the mean ± SEM. The results were analyzed using Student's t-test. Values of p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Abbreviations

- Aurka

Aurora kinase A

- Bcl2l10

Bcl-2-like-10

- Cep192

Centrosomal protein of 192kDa

- dsRNA

Double-stranded RNA

- GV

Germinal vesicle

- GVBD

Germinal vesicle breakdown

- HEK293T

Human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293T

- IBMX

3-Isobutyl-1-methyl-xanthine

- MI

Metaphase I

- MII

Metaphase II

- MTOC

Microtubule-organizing center

- PVA

Polyvinyl alcohol

- RanGTP

Ras-related nuclear protein-GTP

- Tpx2

Targeting protein for Xklp2

- T288

Threonine 288

Supplementary Material

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Funding

This work was supported by a National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean government (MEST) (2012-046741).

References

- [1].Hinds MG, Day CL. Regulation of apoptosis: uncovering the binding determinants. Curr Opin Struct Biol 2005; 15(6):690-9; PMID:16263267; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.sbi.2005.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Inohara N, Ding L, Chen S, Núñez G. harakiri, a novel regulator of cell death, encodes a protein that activates apoptosis and interacts selectively with survival-promoting proteins Bcl-2 and Bcl-X(L). EMBO J 1997; 16(7):1686-94; PMID:9130713; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/emboj/16.7.1686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Wang K, Yin XM, Chao DT, Milliman CL, Korsmeyer SJ. BID: a novel BH3 domain-only death agonist. Genes Dev 1996; 10(22):2859-69; PMID:8918887; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1101/gad.10.22.2859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Inohara N, Gourley TS, Carrio R, Muñiz M, Merino J, Garcia I, Koseki T, Hu Y, Chen S, Núñez G. Diva, a Bcl-2 homologue that binds directly to Apaf-1 and induces BH3-independent cell death. J Biol Chem 1998; 273(49):32479-86; PMID:9829980; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.273.49.32479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Lee R, Chen J, Matthews CP, McDougall JK, Neiman PE. Characterization of NR13-related human cell death regulator, boo/Diva, in normal and cancer tissues. Biochim Biophys Acta 2001; 1520(3):187-94; PMID:11566354; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0167-4781(01)00268-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Naumann U, Weit S, Wischhusen J, Weller M. Diva/boo is a negative regulator of cell death in human glioma cells. FEBS Lett 2001; 505(1):23-6; PMID:11557035; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0014-5793(01)02768-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Song Q, Kuang Y, Dixit VM, Vincenz C. Boo, a novel negative regulator of cell death, interacts with Apaf-1. EMBO J 1999; 18(1):167-78; PMID:9878060; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/emboj/18.1.167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Yoon SJ, Chung HM, Cha KY, Kim NH, Lee KA. Identification of differential gene expression in germinal vesicle vs. metaphase II mouse oocytes by using annealing control primers. Fertil Steril 2005; 83 (Suppl 1):1293-6; PMID:15831304; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2004.09.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Yoon SJ, Kim JW, Choi KH, Lee SH, Lee KA. Identification of oocyte-specific diva-associated proteins using mass spectrometry. Korean J Fertil Steril 2006; 33:189-98 [Google Scholar]

- [10].Yoon SJ, Kim EY, Kim YS, Lee HS, Kim KH, Bae J, Lee KA. Role of Bcl2-like 10 (Bcl2l10) in regulating mouse oocyte maturation. Biol Reprod 2009; 81(3):497-506; PMID:19439730; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1095/biolreprod.108.073759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Kim EA, Kim KH, Lee HS, Lee SY, Kim EY, Seo YM, Bae J, Lee KA. Downstream genes regulated by Bcl2l10 RNAi in the mouse oocytes. Dev Reprod 2011; 15:61-9 [Google Scholar]

- [12].Kufer TA, Silljé HH, Körner R, Gruss OJ, Meraldi P, Nigg EA. Human Tpx2 is required for targeting Aurora-A kinase to the spindle. J Cell Biol 2002; 158(4):617-23; PMID:12177045; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1083/jcb.200204155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Gruss OJ, Vernos I. The mechanism of spindle assembly: functions of Ran and its target Tpx2. J Cell Biol 2004; 166(7):949-55; PMID:15452138; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1083/jcb.200312112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Gruss OJ, Wittmann M, Yokoyama H, Pepperkok R, Kufer T, Silljé H, Karsenti E, Mattaj IW, Vernos I. Chromosome-induced microtubule assembly mediated by Tpx2 is required for spindle formation in HeLa cells. Nat Cell Biol 2002; 4(11):871-9; PMID:12389033; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/ncb870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Brunet S, Dumont J, Lee KW, Kinoshita K, Hikal P, Gruss OJ, Maro B, Verlhac MH. Meiotic regulation of Tpx2 protein levels governs cell cycle progression in mouse oocytes. PLOS ONE 2008; 3(10):e3338; PMID:18833336; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0003338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Asteriti IA, Rensen WM, Lindon C, Lavia P, Guarguaglini G. The Aurora-A/Tpx2 complex: a novel oncogenic holoenzyme? Biochim Biophys Acta 2010; 1806(2):230-9; PMID:20708655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Barr AR, Gergely F. Aurora-A: the maker and breaker of spindle poles. J Cell Sci 2007; 120(17):2987-96; PMID:17715155; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1242/jcs.013136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Marumoto T, Zhang D, Saya H. Aurora-A - a guardian of poles. Nat Rev Cancer 2005; 5(1):42-50; PMID:15630414; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nrc1526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Fu J, Bian M, Jiang Q, Zhang C. Roles of Aurora kinases in mitosis and tumorigenesis. Mol Cancer Res 2007; 5(1):1-10; PMID:17259342; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-06-0208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Katayama H, Sasai K, Kloc M, Brinkley BR, Sen S. Aurora kinase-A regulates kinetochore/chromatin associated microtubule assembly in human cells. Cell Cycle 2008; 7(17):2691-704; PMID:18773538; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/cc.7.17.6460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Anand S, Penrhyn-Lowe S, Venkitaraman AR. Aurora-A amplification overrides the mitotic spindle assembly checkpoint, inducing resistance to Taxol. Cancer Cell 2003; 3(1):51-62; PMID:12559175; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S1535-6108(02)00235-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Lu LY, Wood JL, Ye L, Minter-Dykhouse K, Saunders TL, Yu X, Chen J. Aurora A is essential for early embryonic development and tumor suppression. J Biol Chem 2008; 283(46):31785-90; PMID:18801727; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M805880200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Bayliss R, Sardon T, Vernos I, Conti E. Structural basis of Aurora-A activation by Tpx2 at the mitotic spindle. Mol Cell 2003; 12(4):851-62; PMID:14580337; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S1097-2765(03)00392-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Dutertre S, Cazales M, Quaranta M, Froment C, Trabut V, Dozier C, Mirey G, Bouché JP, Theis-Febvre N, Schmitt E, et al. . Phosphorylation of CDC25B by Aurora-A at the centrosome contributes to the G2-M transition. J Cell Sci 2004; 117(12):2523-31; PMID:15128871; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1242/jcs.01108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Saskova A, Solc P, Baran V, Kubelka M, Schultz RM, Motlik J. Aurora kinase A controls meiosis I progression in mouse oocytes. Cell Cycle 2008; 7(15):2368-76; PMID:18677115; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/cc.6361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Dodson CA, Bayliss R. Activation of Aurora-A kinase by protein partner binding and phosphorylation are independent and synergistic. J Biol Chem 2012; 287(2):1150-7; PMID:22094468; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M111.312090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Solc P, Baran V, Mayer A, Bohmova T, Panenkova-Havlova G, Saskova A, Schultz RM, Motlik J. Aurora kinase A drives MTOC biogenesis but does not trigger resumption of meiosis in mouse oocytes matured in vivo. Biol Reprod 2012; 87(4):85; PMID:22837479; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1095/biolreprod.112.101014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Solc P, Kitajima TS, Yoshida S, Brzakova A, Kaido M, Baran V, Mayer A, Samalova P, Motlik J, Ellenberg J. Multiple requirements of Plk1 during mouse oocyte maturation. PLOS ONE 2015; 10(2):e0116783; PMID:25658810; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0116783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Zhai R, Yuan YF, Zhao Y, Liu XM, Zhen YH, Yang FF, Wang L, Huang CZ, Cao J, Huo LJ. Bora regulates meiotic spindle assembly and cell cycle during mouse oocyte meiosis. Mol Reprod Dev 2013; 80(6):474-87; PMID:23610072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Giesecke A, Stewart M. Novel binding of the mitotic regulator Tpx2 (target protein for Xenopus kinesin-like protein 2) to importin-alpha. J Biol Chem 2010; 285(23):17628-35; PMID:20335181; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M110.102343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Dumont J, Petri S, Pellegrin F, Terret ME, Bohnsack MT, Rassinier P, Georget V, Kalab P, Gruss OJ, Verlhac MH. A centriole- and RanGTP-independent spindle assembly pathway in meiosis I of vertebrate oocytes. J Cell Biol 2007; 176(3):295-305; PMID:17261848; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1083/jcb.200605199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Joukov V, De Nicolo A, Rodriguez A, Walter JC, Livingston DM. Centrosomal protein of 192 kDa (Cep192) promotes centrosome-driven spindle assembly by engaging in organelle-specific Aurora A activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010; 107(49):21022-7; PMID:21097701; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.1014664107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Joukov V, Walter JC, De Nicolo A. The Cep192-organized Aurora A-Plk1 cascade is essential for centrosome cycle and bipolar spindle assembly. Mol Cell 2014; 55(4):578-91; PMID:25042804; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.06.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Giubettini M, Asteriti IA, Scrofani J, De Luca M, Lindon C, Lavia P, Guarguaglini G. Control of Aurora-A stability through interaction with Tpx2. J Cell Sci 2011; 124(1):113-22; PMID:21147853; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1242/jcs.075457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Satinover DL, Leach CA, Stukenberg PT, Brautigan DL. Activation of Aurora-A kinase by protein phosphatase inhibitor-2, a bifunctional signaling protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2004; 101(23):8625-30; PMID:15173575; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.0402966101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Lee MT, Bonneau AR, Giraldez AJ. Zygotic genome activation during the maternal-to-zygotic transition. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 2014; 30:581-613; PMID:25150012; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-100913-013027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Su YQ, Sugiura K, Woo Y, Wigglesworth K, Kamdar S, Affourtit J, Eppig JJ. Selective degradation of transcripts during meiotic maturation of mouse oocytes. Dev Biol 2007; 302(1):104-17; PMID:17022963; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.09.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Ding J, Swain JE, Smith GD. Aurora kinase-A regulates microtubule organizing center (MTOC) localization, chromosome dynamics, and histone-H3 phosphorylation in mouse oocytes. Mol Reprod Dev 2011; 78(2):80-90; PMID:21274965; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/mrd.21272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Yao LJ, Zhong ZS, Zhang LS, Chen DY, Schatten H, Sun QY. Aurora-A is a critical regulator of microtubule assembly and nuclear activity in mouse oocytes, fertilized eggs, and early embryos. Biol Reprod 2004; 70(5):1392-9; PMID:14695913; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1095/biolreprod.103.025155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Clift D, Schuh M. A three-step MTOC fragmentation mechanism facilitates bipolar spindle assembly in mouse oocytes. Nat Commun 2015; 6:7217; PMID:26147444; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/ncomms8217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Seki A, Coppinger JA, Jang CY, Yates JR, Fang G. Bora and the kinase Aurora a cooperatively activate the kinase Plk1 and control mitotic entry. Science 2008; 320(5883):1655-8; PMID:18566290; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1126/science.1157425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Macurek L, Lindqvist A, Medema RH. Aurora-A and hBora join the game of Polo. Cancer Res 2009; 69(11):4555-8; PMID:19487276; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Eckerdt F, Pascreau G, Phistry M, Lewellyn AL, DePaoli-Roach AA, Maller JL. Phosphorylation of Tpx2 by Plx1 enhances activation of Aurora A. Cell Cycle 2009; 8(15):2413-9; PMID:19556869; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/cc.8.15.9086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Tong C, Fan HY, Lian L, Li SW, Chen DY, Schatten H, Sun QY. Polo-like kinase-1 is a pivotal regulator of microtubule assembly during mouse oocyte meiotic maturation, fertilization, and early embryonic mitosis. Biol Reprod 2002; 67(2):546-54; PMID:12135894; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1095/biolreprod67.2.546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Fujiwara T, Bandi M, Nitta M, Ivanova EV, Bronson RT, Pellman D. Cytokinesis failure generating tetraploids promotes tumorigenesis in p53-null cells. Nature 2005; 437(7061):1043-7; PMID:16222300; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature04217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Meraldi P, Honda R, Nigg EA. Aurora kinases link chromosome segregation and cell division to cancer susceptibility. Curr Opin Genet Dev 2004; 14(1):29-36; PMID:15108802; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.gde.2003.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Lindsey SF, Byrnes DM, Eller MS, Rosa AM, Dabas N, Escandon J, Grichnik JM. Potential role of meiosis proteins in melanoma chromosomal instability. J Skin Cancer 2013; 2013:190109; PMID:23840955; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1155/2013/190109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Terret M, Chaigne A, Verlhac M. Mouse oocyte, a paradigm of cancer cell. Cell Cycle 2013; 12(21):3370-6; PMID:24091531; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/cc.26583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.