Abstract

Nuclear LIM-only (LMO) and LIM-homeodomain (LIM-HD) proteins have important roles in cell fate determination, organ development and oncogenesis. These proteins contain tandemly arrayed LIM domains that bind the LIM interaction domain (LID) of the nuclear adaptor protein LIM domain-binding protein-1 (Ldb1). We have determined a high-resolution X-ray crystal structure of LMO4, a putative breast oncoprotein, in complex with Ldb1-LID, providing the first example of a tandem LIM:Ldb1-LID complex and the first structure of a type-B LIM domain. The complex possesses a highly modular structure with Ldb1-LID binding in an extended manner across both LIM domains of LMO4. The interface contains extensive hydrophobic and electrostatic interactions and multiple backbone–backbone hydrogen bonds. A mutagenic screen of Ldb1-LID, assessed by yeast two-hybrid and competition ELISA analysis, identified key features at the interface and revealed that the interaction is tolerant to mutation. These combined properties provide a mechanism for the binding of Ldb1 to numerous LMO and LIM-HD proteins. Furthermore, the modular extended interface may form a general mode of binding to tandem LIM domains.

Keywords: Ldb1, LIM, LMO4 domains, protein interactions, tandem binding

Introduction

LIM domains are specialized zinc-fingers that bind two zinc atoms. The acronym comes from the initials of the first three LIM-containing proteins in which the domain was identified, LIN11, Isl-1 and MEC3 (Freyd et al, 1990). The four types of LIM domains (A–D; classified according to sequence homology by Dawid et al, 1998) have been found only in eukaryotes, as part of proteins with diverse functions, such as transcription factors, cytoskeletal proteins and protein kinases. These LIM-containing proteins can include tandem arrays of up to five LIM domains. The only well-documented function of LIM domains is their ability to mediate specific protein:protein interactions (Gill, 1995).

The four LIM-only (LMO) and 12 LIM homeodomain (LIM-HD) proteins encoded by the human genome each contain two tandem LIM domains that possess moderate sequence homology. The sequence of LMO proteins contains little more than the two tandem LIM domains, whereas LIM-HD proteins also carry a DNA-binding homeodomain and may have additional features (Curtiss and Heilig, 1998). LMO and LIM-HD proteins have important roles in cell fate determination, tissue patterning and organ development, with three of the four LMO proteins implicated in oncogenesis. LMO1 and LMO2 (also known as Rhombotin-1 and -2) were originally discovered through their association with specific chromosomal translocations occurring in patients with T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (T-ALL) (Rabbitts et al, 1999). Proviral insertion in the promotor region of LMO2 in severe combined immunodeficiency patients undergoing gene therapy also leads to T-ALL (Hacein-Bey-Abina et al, 2003). LMO2 blocks terminal differentiation of haematopoietic cells (Visvader et al, 1997), and is an obligate regulator of haematopoiesis and angiogenesis (Yamada et al, 1998, 2000). LMO4 was originally identified as a breast cancer autoantigen (Racevskis et al, 1999), and has been shown to be overexpressed in more than 50% of primary breast tumours (Visvader et al, 2001), and in squamous cell carcinomas of the oral cavity (Mizunuma et al, 2003). Lmo4 expression is developmentally regulated in the mammary gland, and overexpression of this gene markedly reduces differentiation of mammary epithelial cells (Visvader et al, 2001; Wang et al, 2004). LMO4 binds to and represses the transcriptional activity of the breast cancer protein 1, BRCA1 (Sum et al, 2002), a tumour suppressor in familial breast cancer. In mice, the targeted disruption of lmo4 leads to defects in neural tube closure, sphenoid bone formation and anteroposterior patterning (Hahm et al, 2004; Tse et al, 2004). The expression of specific LIM-HDs is important in the early stages of cell fate determination and organ development (reviewed by Bach, 2000), and targeted disruption of these proteins is often fatal. For example, Lhx1-deficient mice lack head structures (Shawlot and Behringer, 1995), Lhx2-null mice lack eyes and are devoid of definitive erythropoiesis (Porter et al, 1997), whereas Lhx3-mutant mice lack four of the five anterior pituitary cell types (Sheng et al, 1996).

The tandem LIM domains of all LMO and LIM-HD proteins bind the LIM domain-binding protein, Ldb1 (otherwise known as NLI and CLIM2), through the 39-residue LIM interaction domain (LID) near the C-terminus of this protein (Jurata and Gill, 1997). Ldb1-LID has not been found to interact with any other types of LIM-containing proteins. Ldb1 is a widely expressed nuclear adaptor protein that also contains an N-terminal dimerization domain, and several other binding domains (reviewed by Matthews and Visvader, 2003). Ablation of the Ldb1 gene in mice leads to embryonic lethality with numerous developmental defects, many of which appear to be linked to the disruption of LMO and LIM-HD activity (Mukhopadhyay et al, 2003). The presence of Ldb1 is essential for many of the biological activities of LIM-HD proteins, and Ldb1 has been found in complex with LMO proteins in numerous cell types (Wadman et al, 1997; Grutz et al, 1998b; Valge-Archer et al, 1998; Mizunuma et al, 2003). Dimerization of Ldb1 enables the formation of tetrameric or higher order complexes with LIM-HD and/or LMO proteins that function together to determine cell fate (Jurata et al, 1998; Milan and Cohen, 1999; van Meyel et al, 1999; Thaler et al, 2002). Polypeptides that contain Ldb1-LID but lack the dimerization domain are effective dominant-negative regulators of LIM-HD activity (Bach et al, 1999; Becker et al, 2002). LMO proteins can regulate the transcriptional activity of LIM-HD proteins by competing for binding to Ldb1 (Milan et al, 1998; Shoresh et al, 1998; Zeng et al, 1998), and it has been proposed that displacement of LMO4 by LMO2, as the normal binding partner for Ldb1, is the mechanism by which LMO2-induced T-ALLs occur (Grutz et al, 1998a). In general, LMO proteins are found in the nucleus, but lack a nuclear localization sequence and it is thought that binding to Ldb1 maintains these proteins in the nucleus.

To gain a more detailed understanding of the nature of tandem LIM:Ldb1 interactions, we have solved the high-resolution (1.3 Å) crystal structure of a complex comprising near full-length LMO4 and Ldb1-LID. The structure reveals that the proteins form a rod-shaped complex with Ldb1-LID bound in an extended manner across the entire length of both LIM domains of LMO4 to form a tandem β-zipper. Using a yeast-based mutagenic screen, we have defined the key residues that stabilize this complex and have determined that many mutations still permit moderate-to-high affinity binding. Each LIM domain is individually sufficient to mediate an interaction with Ldb1-LID, but the tandem nature of the complex links these two weaker interactions to form an extended complex of significantly higher binding affinity.

Results

Production and characterization of an intramolecular LMO4–Lb1-LID complex

When produced in a recombinant fashion, the isolated LIM domains from LMO and LIM-HD proteins tend to be unstable and insoluble (Jurata et al, 1998; Deane et al, 2001). In order to produce a stable form of LMO4, we engineered a chimaeric protein comprising the LIM domains of LMO4, followed by an 11-residue flexible linker (GGSGGSGGSGG), and Ldb1-LID (Figure 1A). This chimaeric protein is stable and soluble. In order to show that the structure of this intramolecular complex is identical to that of the intermolecular complex, we produced a variant of the chimaeric protein that contains a protease site in the linker region. 15N-HSQC spectra were acquired using a uniformly 15N-labelled sample of that variant before and after cleavage of the linker with protease (Supplementary data). The spectra are essentially identical, apart from a few minor changes in chemical shift that can be attributed to residues at, or close to, the new termini formed by cutting the linker. The spectra of the LMO4:Ldb1-LID complex have not yet been fully assigned, but comparison with a spectrum of 15N-labelled Ldb1-LID under the same conditions reveals that few peaks from isolated Ldb1-LID remain unchanged in the complex (Supplementary data). Those that remain the same belong to residues near the C-terminus of Ldb1-LID. Thus, the majority of residues in Ldb1-LID change conformation in the presence of LMO4, suggesting their involvement at the interaction interface.

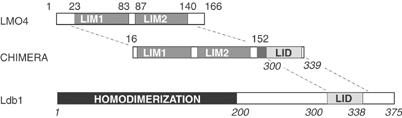

Figure 1.

An LMO4 and Ldb1-LID chimaera construct. Schematic representation of the domains from LMO4 and Ldb1 used in the chimaera. The first and last zinc-ligating residues for each LIM domain and the limits of Ldb1-LID are indicated on those proteins, the regions of each protein combined in the chimaera are indicated on that schematic representation. The LMO4 sequence of the chimaera varies from wild type by the inclusion of the double mutations C52S/C64S. Numbering for Ldb1 is shown in italics. The domains are fused via a GGSGGSGGSGG linker.

Structure of an LMO4:Ldb1-LID complex

We crystallized the intramolecular complex of near full-length LMO4 and Ldb1-LID, and recorded native and multiple wavelength anomalous dispersion data (collected at the Zn X-ray absorption edge) to 1.3 and 1.7 Å resolution, respectively (Deane et al, 2003b). The final refined structure (Table I) comprises residues 19–146 of LMO4 and 300–327 of Ldb1, plus one residue from the linker adjacent to Ldb1-300. Well-resolved electron density was observed for all of these residues (e.g. Figure 2), with the exception of one or more atoms of 10 side chains. No electron density was observed for all other residues in the linker, and the terminal residues of LMO4 (16–18, 147–152) and Ldb1 (328–339). The structure reveals that the complex forms an extended, rod-like structure with approximate dimensions of 80 × 20 × 20 Å (Figure 3A). LMO4 and Ldb1-LID take up an unusual, highly modular conformation, whereby each of the two tandem LIM domains of LMO4 contributes two repeated motifs (i.e. a total of four modules) to bind the elongated Ldb1-LID (Figure 3B).

Table 1.

Refinement statistics for the LMO4:Ldb1-LID complex

| Native data set | |

|---|---|

| Wavelength (Å) | 1.08 |

| Resolution range (Å) | 46.1–1.3 |

| Reflections | 43146 |

| Non-hydrogen atoms | 1448 |

| Solvent molecules | 195 |

| R.m.s.d. bond lengths (Å)a | 0.008 |

| R.m.s.d. bond angles (deg)a | 1.2 |

| Average B-factor (Å2) | 20.0 |

| Rcryst (%)b | 15.5 |

| Rfree (%)c | 19.3 |

| Ramachandran plot statistics | |

| Residues in the most favoured region (%) | 91.0 |

| Residues in the additionally allowed region (%) | 9.0 |

| aRoot mean squared deviation (r.m.s.d.'s) are given from ideal values. | |

| bRcryst=∑hkl∣Fo∣–∣Fc∣/∑hkl ∣Fo∣ for all reflections where Fo and Fc are the observed and calculated structure amplitudes, respectively. | |

| c5% of reflections were excluded for calculation of Rfree. | |

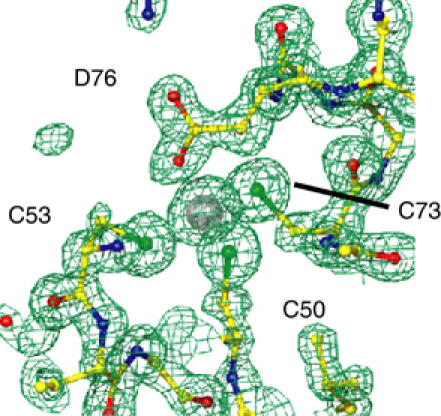

Figure 2.

Zinc coordination by CCCD. 2Fo–Fc electron density map of the CCCD Zn-ligating site of LMO4-LIM1 shown at 2σ.

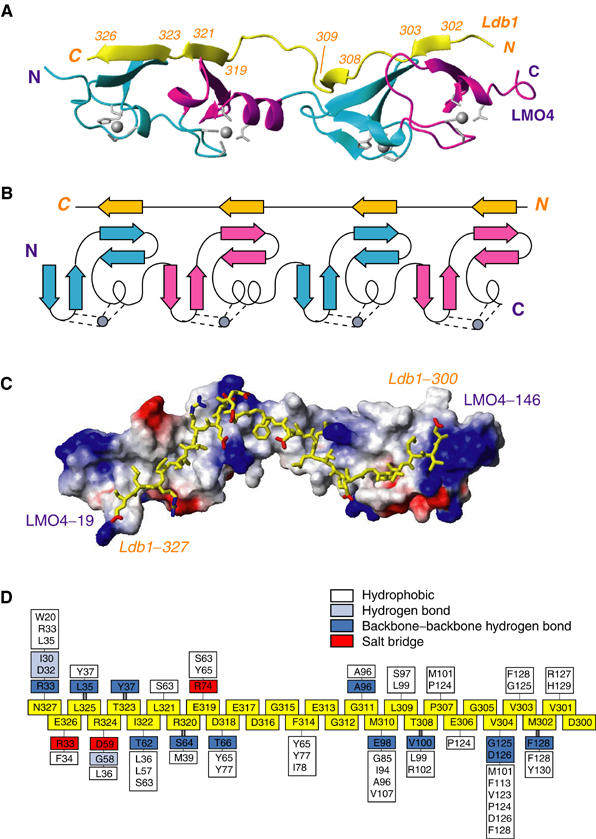

Figure 3.

The structure of an LMO4:Ldb1-LID complex. Numbering for Ldb1 is shown in italics. (A) Ribbon diagram showing the structured regions of Ldb1 (yellow) and LMO4 (with the CCHC Zn modules in cyan and CCCD Zn-binding modules in magenta). Zn-ligating residues and zinc atoms (grey sticks and spheres, respectively) are shown. (B) Schematic representation of the topology of the LMO4:Ldb1-LID complex, colouring as above. (C) Surface charge representation of LMO4 with Ldb1-LID in yellow. Blue corresponds to positive charge, red to negative charge. (D) Schematic representation of the interactions between Ldb1-LID and LMO4. Residues from Ldb1-LID are in the same orientation as for (A–C) (boxed, yellow). Residues from LMO4 that interact with Ldb1-LID are positioned on a skewer directly above or below the relevant Ldb1-LID residues and are distinguished according to the type of interaction: hydrophobic (white), electrostatic (red), side-chain hydrogen bonds (light blue), main-chain hydrogen bonds (dark blue). Pairs of residues that make two backbone:backbone hydrogen bonds to form β-strands in Ldb1-LID are linked by double bold skewers.

Structures of the LIM domains

The tandem arrays of LIM domains from LMO, LIM-HD and LIM-kinase proteins comprise a type A LIM domain closely followed by a type B LIM domain. The structure reported here includes the first published structure of a type B LIM domain. Both the type A LIM domain of LMO4 (LMO4-LIM1, residues 23–76), and the type B LIM domain (LMO4-LIM2, residues 87–140) possess the characteristic double treble-clef structure typical of LIM domains (Grishin, 2001; four β-hairpins followed by a short helix; Figure 3A and B). The only significant difference between the topologies of the two domains is that LMO4-LIM2 possesses a short 310-helix at its C-terminus rather than an α-helix. Each zinc atom is positioned between a pair of β-hairpins so that the tandem LIM structure resembles four closely spaced GATA-type zinc-fingers (Omichinski et al, 1993; Kowalski et al, 1999). An additional turn of 310-helix at the end of the second hairpin in each LIM domain enhances this similarity.

The LMO4-LIM1 portion of the complex is identical to the solution structure of the LMO4-LIM1:Ldb1-LID complex (Deane et al, 2003a); the r.m.s.d. over the backbone atoms of LMO4-LIM1 for the 20 structures in the NMR ensemble (1.0 Å) is unchanged by inclusion of the crystal structure. Since all previous structures of LIM domains were solved using 1H, 15N and 13C NMR spectroscopy, this crystal structure provides the first direct observation of LIM domain zinc coordination sites at high resolution. LMO4-LIM1 and LMO4-LIM2 each have CCHC and CCCD Zn-binding modules with approximately tetrahedral geometry. This is the first structure of a Zn-containing protein with a CCCD ligand set, and of a zinc-finger that ligates Zn(II) using an aspartate side chain (Castagnetto et al, 2002), and clearly shows that the carboxylate group ligates Zn(II) with anti-monodentate geometry (Figure 2). The structures of numerous noncomplexed LIM domains show varied orientations of, and degrees of flexibility between, the two Zn-binding modules (see Deane et al, 2003a; Velyvis et al, 2003 and references therein). Given these differences and the difficulties in isolating LMO4 alone, it remains unclear whether the orientations of the Zn-binding modules within each LIM domain of LMO4 are altered upon binding Ldb1. There are no direct contacts between the two LIM domains in this structure, rather contacts between residues in Ldb1 and each LIM domain appear to determine their orientation with respect to one another.

Ldb1-LID forms a β-zipper interface with LMO4

Ldb1-LID extends across one face of LMO4 and remains in almost continuous contact with the LIM domains over a stretch of 28 residues (D300–N327), to bury a total surface of 3800 Å2 (1450 Å2 from LMO4 and 2360 Å2 from Ldb1, comprising 16 and 52% of the surface of the structured regions of those domains, respectively). An extensive hydrogen-bonding network, formed between the four short β-strands in Ldb1-LID (M302–V303, T308–L309, E319–L321 and T323–E326) and four β-hairpins within LMO4, makes a short three-stranded antiparallel β-sheet at each zinc-binding module (Figure 3A and B and Supplementary data). Although the formation of the β-sheet secondary structure has been observed at the interface of a number of protein complexes, this type of extended interface, termed the tandem β-zipper, has only recently been observed in a fibronectin (FN)-based complex that directs integrin-dependent invasion of cells by pathogenic bacteria (Schwarz-Linek et al, 2003). In that structure, a peptide corresponding to two FN-binding repeats (B3) bound in an extended fashion to tandem FN domains, forming two short β-strands that extend an existing β-sheet within each FN domain. In that example, the peptide ligand maintained two well-folded but otherwise independent FN domains in a fixed orientation.

Apart from hydrogen-bonding networks, the LMO4:Ldb1-LID interaction includes extensive regions of hydrophobic contacts and networks of electrostatic interactions (Figure 3C and D). The interface at the LIM1 domain contains all of the significant electrostatic interactions; E326, R324 and E319 from Ldb1 form salt bridges with R33, D59 and R74, respectively, from LMO4. This interface also contains a more extensive hydrogen-bonding network, including the typical backbone–backbone hydrogen bonds that characterize an antiparallel β-sheet between the four- and three-residue β-strands in Ldb1-LID and LMO4, plus additional hydrogen bonds between the side chains of N327 and R324 in Ldb1 and backbone atoms of LMO4 residues. Numerous hydrophobic contacts at the LIM1 interface are made by residues within and surrounding the two β-sheets. In particular, the side chain of I322 from Ldb1 is almost entirely buried in a hydrophobic pocket formed by residues L36, L57 and S63 between the two zinc-binding modules of LMO4-LIM1. With the exception of Ldb1-F314, the middle of the structured region of Ldb1 comprises mainly charged or glycine residues, which make relatively few contacts. The side chain of Ldb1-F314 points down into the cavity formed between the two LIM domains, which is lined with several hydrophobic side chains, and appears to play an important role in orienting each of the LIM domains with respect to one another. The interface between Ldb1 and LMO4-LIM2 appears to be stabilized by similar, albeit fewer, backbone–backbone hydrogen bonds than for the LMO4-LIM1; the two β-strands in Ldb1 in this domain both comprise only two residues. This region appears to have more hydrophobic contacts that form two small clusters around Ldb1-M310 and Ldb1-V304. The side chains of both these residues are almost completely buried, with Ldb1-V304 taking the equivalent position of Ldb1-I322 lying between the two zinc-binding domains in LMO4-LIM2.

Probing the LMO4:Ldb1 interaction interface

We were unable to implement traditional in vitro binding assays, due to the instability of recombinant LMO4, in order to identify the important features of the LMO4:Ldb1 interface. We therefore used a yeast two-hybrid assay to probe the interactions between constructs of LMO4 and mutants of Ldb1-LID. Although yeast two-hybrid assays are not quantitative, the AH109 strain has different selective markers that give a qualitative measure of interaction affinities. ‘Low-affinity' interactions survive selection on histidine-deficient media, whereas only ‘high-affinity' interactions survive selection on adenine-deficient media.

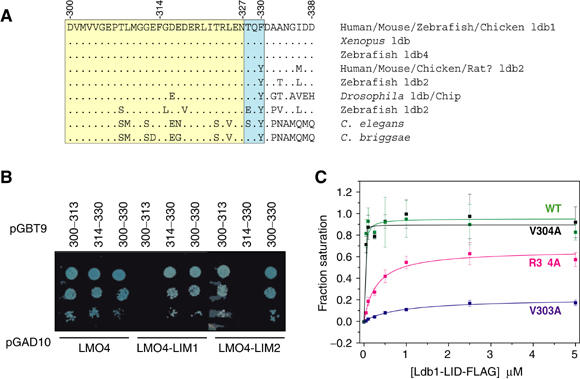

The smallest region of Ldb1 shown by Jurata et al to be sufficient to interact with LMO and LIM-HD proteins was that of residues 300–338 (Jurata and Gill, 1997). The structure of the LMO4:Ldb1-LID complex presented here shows that a shorter sequence (300–327) actually makes contact with the LIM domains; residues 300–313 contact LMO4-LIM2 whereas residues 314–327 contact LMO4-LIM1. Sequence alignments of Ldb proteins in species ranging from nematode to human show that the sequence of LID is highly conserved in this shorter region (Figure 4A). Here, using a yeast two-hybrid assay, Ldb1(300–330) was shown to bind the tandem LIM domains of LMO4 under all selection conditions. However, the binding of the single LIM domains to full-length Ldb1-LID(300–330), LMO4-LIM1 to Ldb1(314–330) and LMO4-LIM2 to Ldb1(300–313) were only detectable on the less-stringent histidine-deficient selection media (Figure 4B). The low-affinity interactions for the LMO4-LIM1:Ldb1-LID complex correspond to association constants of ∼106 M−1 (Deane et al, 2003a), and are likely to be several fold weaker for the LMO4-LIM2:Ldb1-LID interaction, which is poorly detected in coimmunoprecipitation assays (Deane et al, 2003a). In order to gain an estimate of the high-affinity binding of Ldb1-LID to the tandem LIM domains of LMO4, we developed an ELISA based competition assay using the LMO4:Ldb1-LID chimaera (Figure 4C). Purified GST-LMO4:Ldb1-LID containing a Factor Xa site in the linker was cut with Factor Xa to provide an intermolecular GST-LMO4:Ldb1-LID complex to which Ldb1-LID peptides that contain a FLAG tag at their C-terminus (Ldb1-LID-FLAG) are bound. By this method, we determined the IC50 value for wild-type Ldb1-LID-FLAG (i.e. the concentration required to compete off the pre-bound Ldb1-LID and reach half-saturation of GST-LMO4) to be ∼1 nM. The composition and relative concentrations of the starting and competing reagents are such that the association constant cannot be directly measured by this homologous competition assay. However, we can indirectly estimate a lower limit for the association constant of this interaction. We measured the IC50s for several mutant Ldb1-LID-FLAG peptides, which range from being indistinguishable from wild type to ∼1 μM (i.e. ∼1000-fold less effective at competing for binding to LMO4; Figure 4C). We have performed ELISAs using the equivalent LIM1-domain construct as the immobilized reagent and wild-type Ldb1-LID-FLAG as the competitor; however, this interaction is not sufficiently strong to be detected by this method. Thus, the binding affinity between LMO4 and Ldb1-LID is at least 1000-fold greater than LMO4-LIM1 binding (Deane et al, 2003a), giving the lower limit of binding as 109 M−1.

Figure 4.

Dissection of Ldb1-LID. (A) Sequence comparison of the LID from Ldb family members. Dots are conserved residues. The yellow box corresponds to residues that make contact in the crystal structure, blue box to residues that are disordered in the crystal structure but reduce binding to the LMO4-LIM1 domain when all three residues are simultaneously mutated to alanine, possibly affecting the folding properties of Ldb1-LID. (B) Yeast two-hybrid analysis of pGBT9-Ldb-LID versus pGAD10-LMO4 constructs. Data are shown for low-affinity selection –L–W–H (1 mM 3-AT) media. (C) Competition ELISA analysis of Ldb1-LID binding to LMO4. GST-LMO4:Ldb1-LID was incubated with various concentrations of FLAG-tagged Ldb1-LID peptides and the fraction of sites occupied by the FLAG-tagged peptide determined. Wild-type Ldb1-LID-FLAG (green), Ldb1-LID-FLAG_V303A (blue), Ldb1-LID-FLAG_V304A (black) and Ldb1-LID-FLAG_R324A (magenta).

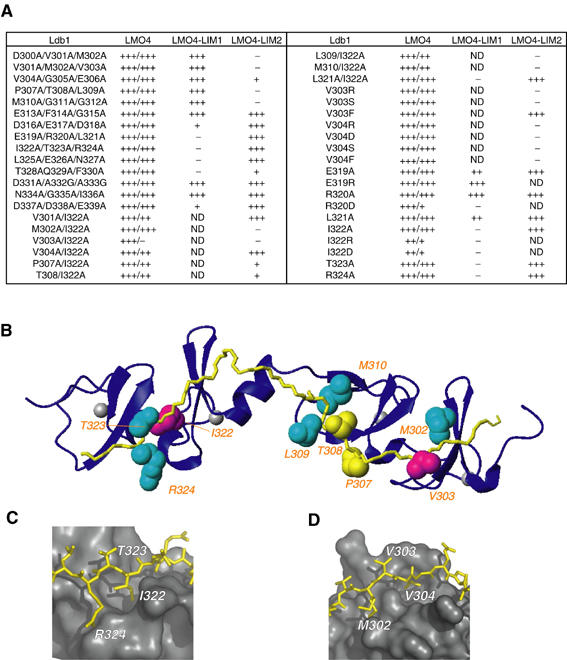

Using the yeast two-hybrid system, the mutation of any three sequential residues in Ldb1-LID to alanine was insufficient to perturb high-affinity binding to the tandem LIM domains of LMO4, although most could disrupt low-affinity binding to single LIM domains (Figure 5A). Note that although mutant D337A/D338A/E339A has a moderate effect on the low-affinity binding to LMO4-LIM1 in this assay, a truncation mutant that lacks this region has no discernable effect on binding to LMO4-LIM1, supporting the structural data showing that residues 337–339 are not directly involved in the LMO4:Ldb1-LID interface. Mutant T328A/Q329A/F330A also affects low-affinity binding to LMO4-LIM1, but based on structural evidence these residues are not directly involved in the interface. It is possible that residues 328–330 may affect the folded state of Ldb1-LID (see discussion). The single mutants M302A, V303A, L309A, M310A, I322A, T323A, R324A, and to a lesser extent P307A and T308A, were unable to bind single LIM domains and, as seen from the crystal structure, the side chains of these residues make significant contributions to the Ldb1:LMO4 interface (Figure 5A and B). From a sample of relative binding affinities measured by ELISA (Figure 4C), a mutation that did not affect binding (V304A) in any yeast two-hybrid experiment also shows no discernable difference in binding affinity. A mutation that has a moderate effect on binding (R324A abrogates binding to LMO4-LIM1 but not to the tandem domains of LMO4 in the yeast two-hybrid assay) competes ∼10–50-fold less effectively for GST-LMO4. Finally, a peptide that carries a key mutation (V303A) competes ∼1000-fold less effectively than the wild-type peptide. More radical mutations (such as introducing charge to a buried hydrophobic residue) have more dramatic effects on binding, but no single mutant we tested was able to fully disrupt ‘high-affinity' binding in the yeast two-hybrid system (i.e. binding affinity remains >106 M−1). It was only when mutations were simultaneously made to key residues in each LIM-domain interface (V303A/I322A) that high-affinity binding to the tandem LIM domains was disrupted. The side chain of I322 is buried in a hydrophobic cavity between the two Zn-binding modules in LMO4-LIM1 (Figure 5C), and the introduction of charged residues at this position significantly decreases binding to the tandem LIM domains. In contrast, the side chain of V303 lies flat on the surface of LMO4, possibly stabilizing a loop of LMO4-LIM2 (Figure 5D). When this residue is mutated to small or charged residues, binding is abrogated, but mutation to phenylalanine, which can potentially form equivalent hydrophobic interactions with LMO4-LIM2, does not disrupt binding. Interestingly, the adjacent residue V304, which is almost entirely buried in a hydrophobic cavity between the two Zn-binding modules in LMO4-LIM2, has no detectable effect on the Ldb1-LID:LMO4-LIM2 interaction when mutated to alanine. This was unexpected based upon analysis of the LMO4:Ldb1 structure given the significant side-chain hydrophobic interactions and its buried position in LIM2 equivalent to that of I322 in LIM1. However, as expected, mutation to a charged, polar or bulky aromatic side chain does disrupt binding, suggesting that small rearrangements between the two zinc-binding modules in the LIM domain can compensate for the partial truncation of valine but cannot accommodate buried polar groups or large side chains.

Figure 5.

Hotspots in the LMO4:Ldb1-LID interface. (A) Mutagenic scanning of Ldb1-LID. High-affinity/low-affinity selection data on –L–W–H–A and –L–W–H (1 mM 3-AT) media, respectively, are reported for Ldb1-LID:LMO4 interactions. Experiments involving single LIM domains are reported for low-affinity –L–W–H (1 mM 3-AT) media only. (B) Ribbon diagram of the LMO4:Ldb1-LID complex showing Ldb1-LID in yellow and LMO4 in blue. Residues important for binding are shown in CPK representation, magenta for the strongest effect, cyan for moderate effect, yellow for weak effect. (C) I322 is buried in a hydrophobic pocket between the two Zn-binding modules of LMO4-LIM1. (D) The side chain of V303 lies flat on the surface of LMO4-LIM2, whereas V304 is buried in a hydrophobic pocket. Alternate positions of the side chain of M302 are shown.

Discussion

The crystal structure of the complex formed by LMO4 and Ldb1-LID provides precise information about the nature of the interaction interface, allowing a detailed understanding of how LIM domains interact with a binding partner. The LMO4 portion of the structure has confirmed that the B-type LIM domain maintains the same overall topology as other types of LIM domains (first described for the C-terminal LIM domain of avian cysteine-rich protein (CRP) by Perez-Alvarado et al, 1994), despite differences in the identity of zinc-ligating residues and the lengths of loops between those residues.

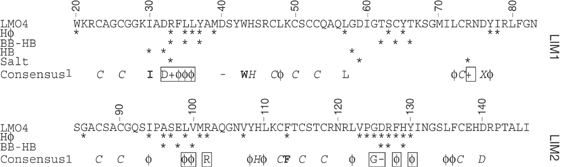

GST-pulldown and immunoprecipitation assays have shown that the isolated LIM1 domains of some LMO and LIM-HD proteins exhibit a greater binding affinity than LIM2 for Ldb1; for others, LIM2 has the greater binding affinity. In general, however, the high-affinity binding of LMO and LIM-HD proteins to Ldb1 requires both LIM domains to be present. Indeed, many LIM-HD proteins require both LIM domains to mediate any detectable interaction (Jurata et al, 1996; Jurata and Gill, 1997; Breen et al, 1998). The considerable sequence variation among these LIM domains (Figure 6 and Supplementary data) must give rise to variations in individual LIM:Ldb1-LID binding affinities. The mutations of Ldb1-LID described in this study reveal that significant levels of binding to LMO4 LIM domains can be maintained despite multiple changes to the LID sequence. Specifically, mutations that, from inspection of the structure, remove substantial hydrophobic contacts (e.g., I322A/T323A/R324A, Figure 5C) maintain moderate to high levels of binding to the tandem LIM domains. Thus, in a tandem β-zipper, very weak associations (i.e., the Ldb1-LID mutant I322A/T323A/R324A to LMO4-LIM1) can combine with moderate affinity interactions (Ldb1-LID(300–313) to LMO4-LIM2) to stabilize the complex. Multiple interactions of varying strengths between Ldb1-LID and each individual LIM domain act in synergy to generate a much higher affinity interaction. The relative tolerance of the tandem β-zipper to mutation of ldb1-LID demonstrates the advantages of forming an extensive interface through the binding of multiple domains. This feature of tolerance to mutation provided by the modular interface, in concert with the numerous backbone–backbone interactions that lead to β-sheet formation (i.e., nonsequence-specific information), provides a mechanism by which Ldb1 can bind multiple LMO and LIM-HD family members of only moderate sequence homology. However, Ldb1 must possess some binding specificity as it does not bind the type A and B LIM domains from LIM kinases, which have similar levels of homology, nor does it bind the type C and D LIM domains. We have shown previously that at least part of this specificity comes from a small cluster of hydrophobic residues in LMO4 at the LMO4-LIM1:Ldb1 interface; mutation of these residues to the equivalent residues in LIM kinase abrogates the binding of Ldb1-LID to LMO4 (Deane et al, 2003a). Two other moderately conserved patches in the LMO and LIM-HD proteins are also found at the LMO4-LIM2:Ldb1-LID interface (Figure 6) and form the hydrophobic pockets in which the side chains Ldb1-V304 and Ldb1-M310 are buried (Figure 3D). Within these regions, we can identify some key nonconserved residues that may represent hot spots for differences in binding affinity for Ldb1-LID. For example, in all LMO/LIM-HD sequences where the residue at position 101 differs from methionine, it is an arginine. In our structure, M101 partakes in hydrophobic interactions with residues P307 and V304 of Ldb1-LID, whereas an arginine at position 101 could form a salt bridge with E306. It should be noted that, of the 23 fully conserved residues, 16 are the zinc-binding ligands and two form hydrophobic cores. The remaining five fully conserved and over half of the 20 highly conserved residues make contacts with Ldb1-LID.

Figure 6.

Conservation of a tandem LIM:Ldb1-LID interface. Numbering refers to the sequence of LMO4. The consensus sequence of LMO and LIM-HD proteins (CONSENSUS 1) was generated from the sequence of human LMO(1–4), LHX(1–9), ISL1 and 2, and LMX1a and b (see Supplementary data for a full sequence alignment of these domains). Only fully conserved residues or residue types are reported as the standard one-letter code, or X used to represent zinc-ligating D or H, φ to represent bulky hydrophobic residues (I, L, V, M, Y, F), − to represent residues with a negative side chain (D or E) and + to represent residues K or R. Hydrophobic (Hφ), Hydrogen bond (non-backbone–backbone, HB; and backbone–backbone, BB–HB) and salt-bridge contacts between LMO4 and Ldb1-LID are indicated. Residues in bold are important hydrophobic core residues. Residues in italics are zinc-ligating residues. The consensus sequence was compared with the sequence of dLMO (beadex) from Drosophila melanogaster and LIN-11 from Caenorhabditis elegans, and applies equally to those proteins. Boxed residues are those which make contributions to the LMO4:Ldb1 interface and are highly conserved in the LMO/LIM-HD family but not in other LIM domains.

Variations in binding affinity between Ldb1-LID and different tandem LIMs have important consequences for the biological roles of LMO and LIM-HD proteins. LMO proteins tend to bind Ldb1 with apparently higher affinity than LIM-HD proteins. This feature, combined with the overlapping expression patterns of LMO and LIM-HD proteins, allows LMO proteins to downregulate the activity of LIM-HD proteins by competing for this essential cofactor. Competition for binding to Ldb1 among different LIM-HD proteins must also play an important role in cell fate determination during neuronal development, where the expression of different combinations of LIM-HD proteins leads to differentiation of various cell types. For example, the adjacent cell types that give rise to V2 interneurons and motorneurons both express Lhx3, but the latter also express Isl-1. Thaler et al (2002) showed that Lhx3 contacts Ldb1 in interneurons, but when both LIM-HD proteins are present in motorneurons it is Isl-1 not Lhx3 that contacts Ldb1 directly.

The LID domain of Ldb proteins has a very high level of conservation compared with the rest of the protein (Figure 4A; Matthews and Visvader, 2003). The requirement for this domain to contact multiple LMO and LIM-HD proteins of varied sequence with different specific binding activities is likely to be a major contributor to this conservation. In addition, Ldb1-LID binds LIM domains of LMO and LIM-HD proteins in an extended conformation; therefore, the sequence must be under some selection pressure to maintain an unfolded conformation. This requirement to not form a compact structure, such as α-helices or β-hairpins, is due to the very unfavourable energetic costs of unfolding prior to binding. Sequence conservation in Ldb1-LID must also arise, at least in part, because Ldb1-LID is used to contact other non-LIM partners, such as bHLH proteins (Ramain et al, 2000). This ability to bind many different proteins is thought to be important in determining the composition of larger multi-protein complexes. Indeed, Ldb1 and LMO proteins have been found in many such complexes (e.g., see references Wadman et al, 1997; Grutz et al, 1998b; Sum et al, 2002), and the new surfaces created by tandem LIM:Ldb1-LID interactions may be necessary for binding to further proteins within these complexes.

Most LIM proteins contain multiple LIM domains and bind multiple partner proteins. For example, FHL proteins are named for their four and a half tandem LIM domains and PINCH (potentially interesting new cysteine/histidine rich) proteins contain five tandemly arrayed LIM domains. Some of the protein:protein interactions that involve these LIM proteins are mediated by a single LIM domain (Tu et al, 1999), but many require the presence of multiple LIM domains (Turner et al, 2003; Wei et al, 2003). Many LIM-binding proteins possess repeat regions, suggesting that extended binding interfaces, such as the tandem β-zipper, may be a common mode of interaction for this important class of proteins.

In conclusion, in this study we have used LMO4 as a representative model for LMO and LIM-HD proteins, and demonstrated that Ldb1 mediates its interaction with tandem LIM domains by forming an extended tandem β-zipper interface. The extended conformation of Ldb1-LID that is maintained upon binding to LMO4 provides multiple contact points. Along its length, Ldb1-LID is involved in a series of backbone–backbone and specific side chain–side chain interactions, which require the appropriate orientation of the LIM domains of LMO4. The importance of having many different and separate contributions to binding is that it allows Ldb1-LID to satisfy the needs for high-affinity and specific binding while maintaining its versatile interaction with various LIM domains from the LMO and LIM-HD protein families.

Materials and methods

Structure determination and refinement

A chimaeric protein comprising domains from LMO4 (residues 16–152) and Ldb1-LID (residues 300–339) (Figure 1) was crystallized as described previously (Deane et al, 2003b). The construct contains cysteine to serine mutations of non-zinc-ligating cysteines (residues 52 and 64). The structure of the LMO4:Ldb1-LID complex was determined using phase information from MAD data (Deane et al, 2003b) collected at the Zn K-edge with initial phases calculated to 1.7 Å resolution. RESOLVE (Terwilliger, 2001) was used to carry out solvent flattening and initial molecule tracing. Phase extension to 1.3 Å was carried out using ARP/WARP (Perrakis et al, 1999), in addition to further model building, and automatic incorporation of water molecules. Manual manipulation of the structure was performed in O (Jones et al, 1991). All refinement cycles were carried out with REFMAC5 (Murshudov et al, 1997), with the final step incorporating anisotropic temperature factor refinement at all non-hydrogen atoms. Surface area accessibility calculations were carried out with AREAIMOL (Lee and Richards, 1971). Figures were prepared with Pymol (DeLano Scientific LLC) and MolMol (Koradi et al, 1996).

NMR spectroscopy and Factor Xa proteolysis

NMR samples contained 20 mM Tris–HCl (95% H2O/5% D2O), pH 8.0, 0.5 mM TCEP, 100 mM NaCl, 2 mM CaCl2 and 1 μM DSS. Data were acquired at 25°C on a Bruker DRX-600 NMR spectrometer. Factor Xa was added (at a mass ratio of 1:50) to an NMR sample of uniformly 15N-labelled LMO4:Ldb1 chimaera (200 μM) that contains the Factor Xa protease site in the linker region. Proteolysis was allowed to proceed for 14 h at 25°C. 15N-HSQC spectra were recorded prior to the addition of Factor Xa, and at the completion of proteolysis. Samples for analysis were taken at the same times, the reaction stopped by the addition of SDS-loading buffer, and samples analysed by Tris-Tricine SDS–PAGE to determine that proteolysis had reached >90% completion.

Production of Ldb1-LID mutants and yeast two-hybrid assays

Mutants of Ldb1-LID were generated using PCR or overlap extension PCR and subcloned into pGBT9 (Clontech). Tandem LMO4(16–150) and LMO4-LIM2(77–150) were subcloned into pGAD10 (Clontech) and LMO4-LIM1(18–86) into pGADT7 (Clontech). Yeast two-hybrid assays were conducted in yeast strain AH109 (Clontech). pGBT9 and PGAD10/T7 plasmids were transformed pairwise, and maintained using minimal media deficient in leucine and tryptophan throughout all experiments (Yeast Protocol Handbook, Clontech). Liquid cultures were incubated overnight with shaking (220 rpm) at 30°C, normalized for cell concentration by dilution with sterile MilliQ™ H2O such that A600 nm=0.2, diluted serially (2 × 1 in 10), spotted onto appropriate selection plates and incubated at 30°C for ∼72 h. Interactions were screened via the observation of yeast growth and subsequent blue colour development on media lacking histidine and containing 40 μg/ml X-α-gal (Progen) and 1 mM 3-amino-1,2,4-triazole (3-AT, Sigma). More stringent selection media lacked adenine and 3-AT.

ELISA assays

C-terminally FLAG-tagged versions of Ldb1-LID were expressed as glutathione S-transferase (GST) fusions, purified by glutathione affinity chromatography, cleaved from GST with thrombin and then further purified by reversed-phase HPLC. GST-LMO4:ldb1-LID chimaera containing the Factor Xa site in the linker was purified by GSH affinity chromatography, eluted with GSH (10 mM), dialysed and then treated with Factor Xa until >90% of the protein was cut as judged by SDS–PAGE. Stock solutions of the chimaera and peptides were prepared in 10 mM glutathione, 50 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT and 10 μM ZnSO4. Wells of the anti-GST-coated plates (Pierce Reacti-Bind Anti-GST Plates, # 15145) were washed with 3 × 200 μl 20 mM H2NaPO4, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, containing 0.1% Tween-20, 1 mM DTT and 10 μM ZnSO4 (wash buffer) and then incubated with 100 μl of cut GST-LMO4:Ldb1-LID (0.1 mg/ml) at room temperature with gentle agitation for 1 h. The protein solution was removed and the wells washed (3 × 200 μl wash buffer). Ldb1-LID-FLAG peptides were added at 37°C for 2 h with shaking. Peptide solutions were removed and plates washed (3 × 200 μl wash buffer) before addition of 100 μl antibody solution (1:3000 dilution of Sigma ANTI-FLAG M2 Monoclonal Antibody-Peroxidase Conjugate, # A 8592). After gentle shaking (1 h at room temperature), the antibody solution was removed and the plates washed (4 × 200 μl wash buffer lacking 1 mM DTT and 10 μM ZnSO4). Presence of antibody was detected with the TMB Microwell Peroxidase Substrate System (KPL 50-76-00). The amount of bound Ldb1-LID-FLAG was baseline corrected against a GST-only control, and maximal binding levels were determined using intact GST-LMO4:ldb1-LID-FLAG. These levels were reached by wild type.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary data 1

Supplementary data 2

Supplementary data 3

Acknowledgments

JED and DPR are supported by Australian Post Graduate Research Awards. MJM is an Australian Research Council (ARC) Australian Postdoctoral Fellow, JMM was supported by fellowships from the ARC and Viertel Foundation. JEV is supported by the Victorian Breast Cancer Research Consortium. This work has been supported by grants from the ARC and NHMRC. The atomic coordinates have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank with ID code 1RUT.

References

- Bach I (2000) The LIM domain: regulation by association. Mech Dev 91: 5–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bach I, Rodriguez-Esteban C, Carriere C, Bhushan A, Krones A, Rose DW, Glass CK, Andersen B, Izpisua Belmonte JC, Rosenfeld MG (1999) RLIM inhibits functional activity of LIM homeodomain transcription factors via recruitment of the histone deacetylase complex. Nat Genet 22: 394–399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker T, Ostendorff HP, Bossenz M, Schluter A, Becker CG, Peirano RI, Bach I (2002) Multiple functions of LIM domain-binding CLIM/NLI/Ldb cofactors during zebrafish development. Mech Dev 117: 75–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breen JJ, Agulnick AD, Westphal H, Dawid IB (1998) Interactions between LIM domains and the LIM domain-binding protein Ldb1. J Biol Chem 273: 4712–4717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castagnetto JM, Hennessy SW, Roberts VA, Getzoff ED, Tainer JA, Pique ME (2002) MDB: the Metalloprotein Database and Browser at The Scripps Research Institute. Nucleic Acids Res 30: 379–382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtiss J, Heilig JS (1998) DeLIMiting development. BioEssays 20: 58–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawid IB, Breen JJ, Toyama R (1998) LIM domains: multiple roles as adapters and functional modifiers in protein interactions. Trends Genet 14: 156–162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deane JE, Mackay JP, Kwan AH, Sum EY, Visvader JE, Matthews JM (2003a) Structural basis for the recognition of ldb1 by the N-terminal LIM domains of LMO2 and LMO4. EMBO J 22: 2224–2233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deane JE, Maher MJ, Langley DB, Graham SC, Visvader JE, Guss JM, Matthews JM (2003b) Crystallization of FLINC4, an intramolecular LMO4–ldb1 complex. Acta Crystallogr D 59: 1484–1486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deane JE, Sum E, Mackay JP, Lindeman GJ, Visvader JE, Matthews JM (2001) Design, production and characterization of FLIN2 and FLIN4: the engineering of intramolecular LMO/ldb1 complexes. Prot Eng 14: 493–494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freyd G, Kim SK, Horvitz HR (1990) Novel cysteine-rich motif and homeodomain in the product of the Caenorhabditis elegans cell lineage gene lin-11. Nature 344: 876–879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill GN (1995) The enigma of LIM domains. Structure 3: 1285–1289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grishin NV (2001) Treble clef finger—a functionally diverse zinc-binding structural motif. Nucleic Acids Res 29: 1703–1714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grutz G, Forster A, Rabbitts TH (1998a) Identification of the LMO4 gene encoding an interaction partner of the LIM-binding protein LDB1/NLI1: a candidate for displacement by LMO proteins in T cell acute leukaemia. Oncogene 17: 2799–2803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grutz GG, Bucher K, Lavenir I, Larson T, Larson R, Rabbitts TH (1998b) The oncogenic T cell LIM-protein Lmo2 forms part of a DNA-binding complex specifically in immature T cells. EMBO J 17: 4594–4605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hacein-Bey-Abina S, Von Kalle C, Schmidt M, McCormack MP, Wulffraat N, Leboulch P, Lim A, Osborne CS, Pawliuk R, Morillon E, Sorensen R, Forster A, Fraser P, Cohen JI, de Saint Basile G, Alexander I, Wintergerst U, Frebourg T, Aurias A, Stoppa-Lyonnet D, Romana S, Radford-Weiss I, Gross F, Valensi F, Delabesse E, Macintyre E, Sigaux F, Soulier J, Leiva LE, Wissler M, Prinz C, Rabbitts TH, Le Deist F, Fischer A, Cavazzana-Calvo M (2003) LMO2-associated clonal T cell proliferation in two patients after gene therapy for SCID-X1. Science 302: 415–419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahm K, Sum EYM, Fujiwara YJG, Lindeman GJ, Visvader JE, Orkin SH (2004) Defective neural tube closure and anteroposterior patterning in mice lacking the LIM protein Lmo4 or its interacting partner Deaf-1. Mol Cell Biol 24: 2074–2082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones TA, Zou JY, Cowan SW, Kjeldgaard M (1991) Improved methods for building protein models in electron density maps and the location of errors in these models. Acta Crystallogr A 47: 110–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurata LW, Gill GN (1997) Functional analysis of the nuclear LIM domain interactor NLI. Mol Cell Biol 17: 5688–5698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurata LW, Kenny DA, Gill GN (1996) Nuclear LIM interactor, a rhombotin and LIM homeodomain interacting protein, is expressed early in neuronal development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93: 11693–11698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurata LW, Pfaff SL, Gill GN (1998) The nuclear LIM domain interactor NLI mediates homo- and heterodimerization of LIM domain transcription factors. J Biol Chem 273: 3152–3157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koradi R, Billeter M, Wüthrich K (1996) MOLMOL: a program for display and analysis of macromolecular structures. J Mol Graphics 14: 51–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowalski K, Czolij R, King GF, Crossley M, Mackay JP (1999) The solution structure of the N-terminal zinc finger of GATA-1 reveals a specific binding face for the transcriptional co-factor FOG. J Biomol NMR 13: 249–262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee B, Richards FM (1971) The interpretation of protein structures: estimation of static accessibility. J Mol Biol 55: 379–400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews JM, Visvader JE (2003) LIM-domain-binding protein 1: a multifunctional cofactor that interacts with diverse proteins. EMBO Rep 4: 1132–1137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milan M, Cohen SM (1999) Regulation of LIM homeodomain activity in vivo: a tetramer of dLDB and apterous confers activity and capacity for regulation by dLMO. Mol Cell 4: 267–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milan M, Diaz-Benjumea FJ, Cohen SM (1998) Beadex encodes an LMO protein that regulates apterous LIM-homeodomain activity in Drosophila wing development: a model for LMO oncogene function. Genes Dev 12: 2912–2920 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizunuma H, Miyazawa J, Sanada K, Imai K (2003) The LIM-only protein, LMO4, and the LIM domain-binding protein, LDB1, expression in squamous cell carcinomas of the oral cavity. Br J Cancer 88: 1543–1548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukhopadhyay M, Teufel A, Yamashita T, Agulnick AD, Chen L, Downs KM, Schindler A, Grinberg A, Huang SP, Dorward D, Westphal H (2003) Functional ablation of the mouse Ldb1 gene results in severe patterning defects during gastrulation. Development 130: 495–505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murshudov GN, Vagin AA, Dodson EJ (1997) Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr D 53: 240–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omichinski JG, Clore GM, Schaad O, Felsenfeld G, Trainor C, Appella E, Stahl SJ, Gronenborn AM (1993) NMR structure of a specific DNA complex of Zn-containing DNA binding domain of GATA-1. Science 261: 438–446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Alvarado GC, Miles C, Michelsen JW, Louis HA, Winge DR, Beckerle MC, Summers MF (1994) Structure of the carboxy-terminal LIM domain from the cysteine rich protein CRP. Nat Struct Biol 1: 388–398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrakis A, Morris R, Lamzin VS (1999) Automated protein model building combined with iterative structure refinement. Nat Struct Biol 6: 458–463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter FD, Drago J, Xu Y, Cheema SS, Wassif C, Huang SP, Lee E, Grinberg A, Massalas JS, Bodine D, Alt F, Westphal H (1997) Lhx2, a LIM homeobox gene, is required for eye, forebrain, and definitive erythrocyte development. Development 124: 2935–2944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabbitts TH, Bucher K, Chung G, Grutz G, Warren A, Yamada Y (1999) The effect of chromosomal translocations in acute leukemias: the LMO2 paradigm in transcription and development. Cancer Res 59: 1794s–1798s [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Racevskis J, Dill A, Sparano JA, Ruan H (1999) Molecular cloning of LMO41, a new human LIM domain gene. Biochim Biophys Acta 1445: 148–153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramain P, Khechumian R, Khechumian K, Arbogast N, Ackermann C, Heitzler P (2000) Interactions between chip and the achaete/scute-daughterless heterodimers are required for pannier-driven proneural patterning. Mol Cell 6: 781–790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz-Linek U, Werner JM, Pickford AR, Gurusiddappa S, Kim JH, Pilka ES, Briggs JA, Gough TS, Hook M, Campbell ID, Potts JR (2003) Pathogenic bacteria attach to human fibronectin through a tandem beta-zipper. Nature 423: 177–181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shawlot W, Behringer RR (1995) Requirement for Lim1 in head-organizer function. Nature 374: 425–430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheng HZ, Zhadanov AB, Mosinger B Jr, Fujii T, Bertuzzi S, Grinberg A, Lee EJ, Huang SP, Mahon KA, Westphal H (1996) Specification of pituitary cell lineages by the LIM homeobox gene Lhx3. Science 272: 1004–1007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoresh M, Orgad S, Shmueli O, Werczberger R, Gelbaum D, Abiri S, Segal D (1998) Overexpression Beadex mutations and loss-of-function heldup-a mutations in Drosophila affect the 3′ regulatory and coding components, respectively, of the Dlmo gene. Genetics 150: 283–299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sum EY, Peng B, Yu X, Chen J, Byrne J, Lindeman GJ, Visvader JE (2002) The LIM domain protein LMO4 interacts with the cofactor CtIP and the tumor suppressor BRCA1 and inhibits BRCA1 activity. J Biol Chem 277: 7849–7856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terwilliger TC (2001) Maximum-likelihood density modification with pattern recognition of structural motifs. Acta Crystallogr D 57: 1755–1762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thaler JP, Lee SK, Jurata LW, Gill GN, Pfaff SL, Bridwell JA, Price JR, Parker GE, McCutchan Schiller A, Sloop KW, Rhodes SJ (2002) LIM factor Lhx3 contributes to the specification of motor neuron and interneuron identity through cell-type-specific protein–protein interactions. Cell 110: 237–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tse E, Smith AJ, Hunt S, Lavenir I, Forster A, Warren AJ, Grutz G, Foroni L, Carlton MB, Colledge WH, Boehm T, Rabbitts TH (2004) Null mutation of the Lmo4 gene or a combined null mutation of the Lmo1/Lmo3 genes causes perinatal lethality, and Lmo4 controls neural tube development in mice. Mol Cell Biol 24: 2063–2073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu Y, Li F, Goicoechea S, Wu C (1999) The LIM-only protein PINCH directly interacts with integrin-linked kinase and is recruited to integrin-rich sites in spreading cells. Mol Cell Biol 19: 2425–2434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner J, Nicholas H, Bishop D, Matthews JM, Crossley M (2003) The LIM protein FHL3 binds basic Kruppel-like factor/Kruppel-like factor 3 and its co-repressor C-terminal-binding protein 2. J Biol Chem 278: 12786–12795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valge-Archer V, Forster A, Rabbitts TH (1998) The LMO1 and Ldb1 proteins interact in human T cell acute leukaemia with the chromosomal translocation t(11;14)(p15;q11). Oncogene 17: 3199–3202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Meyel DJ, O'Keefe DD, Jurata LW, Thor S, Gill GN, Thomas JB (1999) Chip and apterous physically interact to form a functional complex during Drosophila development. Mol Cell 4: 259–265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velyvis A, Vaynberg J, Yang Y, Vinogradova O, Zhang Y, Wu C, Qin J (2003) Structural and functional insights into PINCH LIM4 domain-mediated integrin signaling. Nat Struct Biol 10: 558–564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visvader JE, Mao X, Fujiwara Y, Hahm K, Orkin SH (1997) The LIM-domain binding protein Ldb1 and its partner LMO2 act as negative regulators of erythroid differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94: 13707–13712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visvader JE, Venter D, Hahm K, Santamaria M, Sum EY, O'Reilly L, White D, Williams R, Armes J, Lindeman GJ (2001) The LIM domain gene LMO4 inhibits differentiation of mammary epithelial cells in vitro and is overexpressed in breast cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 14452–14457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wadman IA, Osada H, Grutz GG, Agulnick AD, Westphal H, Forster A, Rabbitts TH (1997) The LIM-only protein Lmo2 is a bridging molecule assembling an erythroid, DNA-binding complex which includes the TAL1, E47, GATA-1 and Ldb1/NLI proteins. EMBO J 16: 3145–3157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang N, Kudryavtseva E, Ch'en IL, McCormick J, Sugihara TM, Ruiz R, Andersen B, Kudryavtseva EI, Lasso RJ, Gudnason JF, Lipkin SM (2004) Expression of an engrailed-LMO4 fusion protein in mammary epithelial cells inhibits mammary gland development in mice. Oncogene 23: 1507–1513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei Y, Renard CA, Labalette C, Wu Y, Levy L, Neuveut C, Prieur X, Flajolet M, Prigent S, Buendia MA (2003) Identification of the LIM protein FHL2 as a coactivator of beta-catenin. J Biol Chem 278: 5188–5194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada Y, Pannell R, Forster A, Rabbitts TH (2000) The oncogenic LIM-only transcription factor Lmo2 regulates angiogenesis but not vasculogenesis in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 320–324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada Y, Warren AJ, Dobson C, Forster A, Pannell R, Rabbitts TH (1998) The T cell leukemia LIM protein Lmo2 is necessary for adult mouse hematopoiesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 3890–3895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng C, Justice NJ, Abdelilah S, Chan YM, Jan LY, Jan YN (1998) The Drosophila LIM-only gene, dLMO, is mutated in Beadex alleles and might represent an evolutionarily conserved function in appendage development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 10637–10642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary data 1

Supplementary data 2

Supplementary data 3