Abstract

Purpose

Chronic graft-versus-host disease (cGVHD) is a significant cause of mortality and morbidity after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant and is associated with a wide range of distressing symptoms. A pediatric measure of cGVHD-related symptoms is needed to advance clinical research. Our aim was to elicit descriptions of the cGVHD symptom experience directly from children and to compare the specific language used by children to describe their symptoms and the comprehension of symptom concepts across the developmental spectrum.

Methods

We used qualitative methods to identify the phrases, terms, and constructs that children (ages 5–8 [n =8], 9–12 [n =8], and 13–17 [n =8]) with cGVHD employ when describing their symptoms. The symptom experience of each participant was determined through individual interviews with each participant and parent (5–7 year olds were interviewed together with a parent). Medical practitioners with experience in evaluating cGVHD performed clinical assessments of each participant.

Results

Pediatric transplant survivors and their parents identified a wide range of bothersome cGVHD symptoms, and common concepts and terminologies to describe these experiences emerged. Overall concordance between patient and parent reports was moderate (70–75 %). No consistent pattern of child under- or over-reporting in comparison to the parent report was observed.

Conclusion

These study results identify concepts and vocabulary to inform item generation for a new pediatric self-report measure of cGVHD symptoms for use in clinical research. The findings also confirm the prevalence and nature of symptom distress in pediatric patients with cGVHD and support implementation of systematic approaches to symptom assessment and intervention in routine clinical practice.

Keywords: Chronic graft-versus-host disease, Stem cell transplant, Pediatric, Symptom scale, Patient-reported outcomes (PROs), Qualitative

Introduction

Chronic graft-versus-host disease (cGVHD) is a condition of immune dysregulation that usually occurs 100 days and beyond following allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. This late complication of transplantation is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in children undergoing transplantation and carries a 59 % survival rate at 5 years after cGVHD diagnosis [1]. Chronic GVHD develops in 20–60 % of transplant recipients [2–4], and its symptoms are heterogeneous, including skin changes (lichenoid and sclerotic changes), joint contractures, severe muscle cramping, sicca syndrome, oral ulcers, esophageal dysmotility, nausea, poor appetite, weight loss, and polyserositis [5, 6]. Chronic GVHD therapy in children is often protracted, and the rate of discontinuation of immunosuppression is only 37 % at 5 years after its diagnosis [1]. Better tools to capture the burden of cGVHD at diagnosis and follow-up are essential to be able to adequately optimize the treatment.

Traditionally, cGVHD has been classified as “limited” or “extensive,” though these distinctions are not particularly useful in clinical practice. The waxing and waning nature of cGVHD and the diversity of its clinical manifestations make management and assessment of this disease very complicated. In 2005, NIH cGVHD individual organ and global severity scoring was proposed to standardize clinician evaluation and staging of cGVHD in an effort to establish consistent response criteria for patients enrolled on clinical trials [7, 8]. Since then, prospective natural history cGVHD studies have shown that the overall severity score as well as individual scores in specific organs such as skin are predictive of survival [9, 10].

Mortality and time to discontinuation of immunosuppressive therapy are often used as endpoints in cGVHD trials. Although objective and important measures of cGVHD, these are not always practical or informative measures of disease burden. Surrogate endpoints are needed and may prove to be more informative and practical in cGVHD clinical trials and in clinical care. One important measure of disease burden is health-related quality of life (HRQOL) [11]. To date, there are no pediatric scales to assess symptoms of cGVHD. Several pediatric measures are being used to evaluate the HRQOL of children living with GVHD such as the PedsQL cancer module [12] for children with cancer, Minneapolis–Manchester Quality of Life (MMQL) [13, 14], and Child Health Ratings Inventories (CHRIs) [15, 16] for survivors of pediatric stem cell transplant. General HRQOL instruments capture domains such as emotional well being (e.g., anxiety and depression), whereas disease-specific instruments capture specific symptoms (e.g., itching, diarrhea, and shortness of breath) directly related to the disease. Because none of these instruments is specific for cGVHD, each has potential content validity limitations in assessing the full spectrum of symptoms experienced by children with cGVHD.

The Lee cGVHD Symptom Scale is a validated measure of the degree to which adults are bothered by each of 30 cGVHD specific symptoms [17]. The Lee Scale correlates with therapeutic response in patients with newly diagnosed cGVHD [18]; however, this measure has not been validated for use in children or their parent proxies. Importantly, item generation for a pediatric symptom scale requires that the symptom concepts and phrasing be identified based on concept elicitations interviews with individuals from the target patient population [19]. No prior research has systematically explored child and parent perspectives of the symptoms associated with cGVHD. The objectives of this study were to inform the development of a pediatric cGVHD symptom scale by describing the physical and emotional symptoms of cGVHD from the child and parent perspective and exploring the language and symptom concepts used by children across the developmental spectrum to describe the cGVHD symptoms they find to be bothersome.

Materials and methods

To ensure the developmental appropriateness of pediatric patient-reported outcome (PRO) measures, both the US Food and Drug Administration [20] and the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR) [19] recommend that qualitative interviews with the targeted patient population be conducted for concept elicitation and to inform item generation and support content validity of new PRO instruments. Because children may use different words than adults when describing their experiences, it is particularly important that the child’s perspective be incorporated when establishing content validity [20]. Thus, a qualitative approach was used to identify the constructs and specific language children with cGVHD use to describe their symptom experience.

Individual interviews were conducted separately with each pediatric cGVHD patient over the age of 8 and with their parent; 5–7 year old participants were interviewed together with a parent. The design and implementation of the study followed the published principles and best practices for successfully conducting cognitive interviews with children [19–21]. This study was approved by the Institutional Review boards at five sites: Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago (formerly Children’s Memorial Hospital), Chicago, IL; University of Minnesota, MN; National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD; Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, OR; and Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, WA. All participants (pediatric patients and their parents) gave informed assent/consent to participate.

Data were extracted from the medical record including underlying disease, type of transplant, stem cell source, donor type, HLA mismatch, time since transplant, prior cGVHD treatment regimens, and current cGVHD treatment regimen. The NIH cGVHD Consensus criteria forms (cGVHD organ score and response criteria form) were completed by a practitioner (physician or advanced practice nurse) with experience in performing comprehensive cGVHD clinical evaluations.

Interview guide

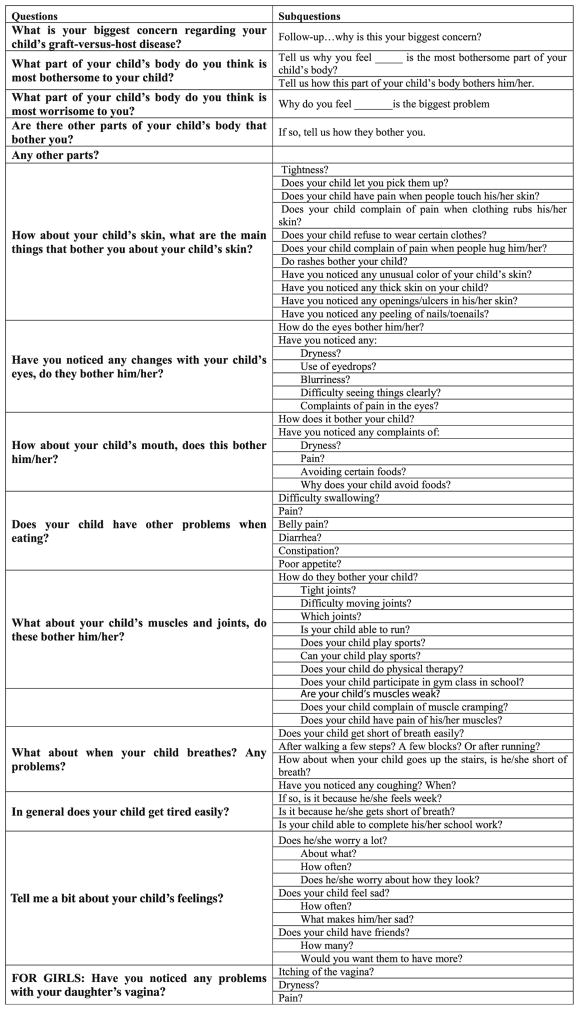

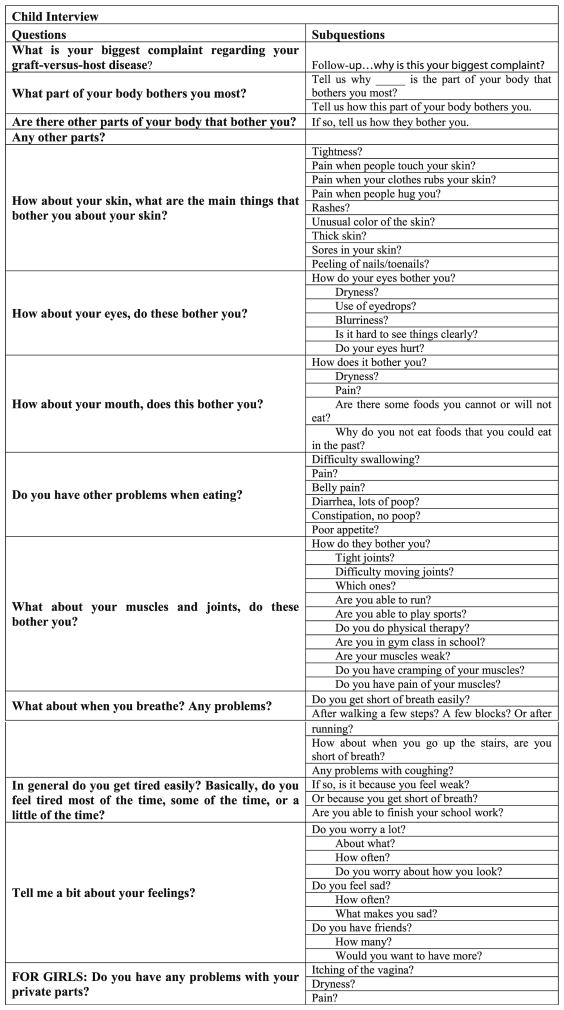

Five experts (three physicians and two nurses) with experience in pediatric hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) and cGVHD developed an interview guide that was used during each of the audio-recorded interviews (Fig. 1a, b). The guides were designed to trigger responses that would optimize the probability that all the symptoms the child was experiencing would be reported during the interview. As the symptoms associated with cGVHD relate directly to the disease pathophysiology and the side effects of immunosuppression, it was assumed that the symptoms experienced by children would be comparable to those of adults (e.g., dry eyes and skin itching), although the associated symptom distress, interference, illness concepts, and language used by children would be different and would vary across the developmental spectrum. Thus, the cGVHD symptoms identified by adults in prior research provided a starting point to develop the open-ended questions [17]. Participants were also encouraged to identify concerns in specific content areas. For example, “What bothers you (your child) or ever bothered you (your child) most about your (your child’s) skin?” and “What are other concerns you have had with your (your child’s) skin?”

Fig. 1.

a Parent interview questions: guide used by the interviewer for parent questions. b Patient interview questions: guide used by the interviewer for patient questions

As quantitative approaches to sample size estimation are not applicable in a qualitative study, researchers considered the variability of the target population characteristics when determining sample size [22]. Interviews continued until saturation, defined as the point at which no new information or themes emerged, was documented [19, 23]. Previous research has found that after 12 interviews, between 88 and 92 % of analysis codes (themes) can be identified [22, 24]. Investigators designed this study with a sample size of 24 (eight participant pairs in each age group) realizing that a second cohort might need to be recruited to achieve saturation.

Participants

Children (ages 5 to 17 years old) with a current clinical diagnosis of cGVHD needing systemic treatment and who were without evidence of primary disease relapse were eligible, together with a parent, to participate in this study. Each member of the dyad provided informed consent or, if applicable, child assent. Study subjects were consecutively recruited by principal investigators at each site, and participants were enrolled after informed consent was obtained.

To represent a broad spectrum of developmental perspectives, the dyads were grouped into three age cohorts (5–8 years, 9–12 years, and 13–17 years), based on the age of the child respondent [20]. Evidence suggests that self-report measures may have limited validity and reliability among respondents younger than age 5 and that assessment of health status in children less than 5 years of age must rely on clinical measures and observational reports of parents or other observers [20]. Accordingly, in our study, 5 to 8 year olds (n =8) were interviewed together with their parent since these younger children were anticipated to have a more limited vocabulary, and a less developed understanding of health and illness concepts, and thus the value of the information they provided would be enhanced by interviewing parent and child together. A total of 40 interviews were conducted (n =16 children alone, 16 parents alone, and 8 parents and children together). The interviews ranged from 20 to 90 min. If the child or parent’s primary language was Spanish, a professional translator was used for the entire interview (n =2).

Conference calls with participating sites took place throughout data collection to ensure data completeness, promote consistency of procedures across study sites, and address study-wide interviewer issues and ongoing recruitment. NIH diagnosis and staging [7] and other demographic and clinical variables were assembled using standardized case report forms, and the audio-recorded interviews together with the case report forms were securely shipped to the study sponsoring PI (DJ) where they were monitored for quality assurance and reviewed for consistency. The audio-recorded interviews were transcribed by a professional transcription service. For the Spanish interviewees, transcripts were first prepared in Spanish and then translated.

Data analysis

The first step of the analysis involved reading through the interview transcripts and developing a coding structure. Using an inductive approach, concept codes were labeled and clearly defined to guide the analysis. To reduce bias, three independent health professionals with experience in qualitative data analysis independently performed the coding of all transcripts using the coding dictionary. Intra-class correlation coefficients (ICC) were calculated to assess inter-rater reliability between the three raters in their coding of the presence of symptoms for both parent and child reports. All ICC were significant, most at the p <0.001 level. The median ICC was 0.91 (range 0.76–1.0).

In order to describe the prevalence of each of the cGVHD symptoms, congruence was sought between coders for each symptom reported (for parent and child report, separately). When discrepancies between coders occurred, one of the investigators was consulted (LW) to reconcile differences (LW). Once congruence was obtained for all symptoms, a detailed description of each endorsed symptom and symptom location was developed for each participant age grouping. Once convergence among coders was achieved for all symptoms, a detailed description of each endorsed symptom was summarized for each participant age grouping. Concept saturation, that is the point at which no new changes to the coding dictionary emerged, was achieved after the analysis of two thirds of the interviews.

Results

Participant characteristics

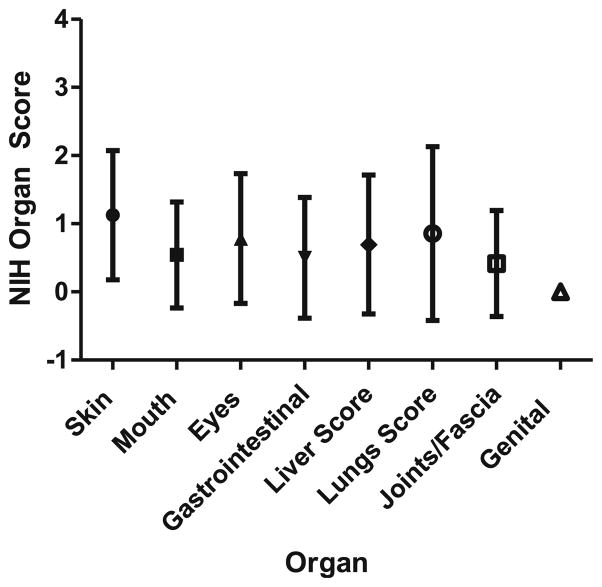

Table 1 details participant characteristics. Participants ranged in age from 5 to 17 years (mean=11). Eighty-three percent were transplanted for a malignancy, and 71 % underwent a full-intensity preparative regimen. Over half (51 %) had been diagnosed with acute GVHD grade II–IV previously. All patients had received multiple therapies for chronic GVHD and the majority were on systematic corticosteroids at the time of interview (92 %). Table 2 details organs involved (NIH score ≥1) by age group and for the whole cohort, and Fig. 2 details the mean (with SD) NIH score for each organ.

Table 1.

Subject characteristics

| Age in years, median (range) | 11 (5–17) |

| Gender | 13 male |

| 11 female | |

| Underlying disease | |

| Malignant | 20 (83 %) |

| Nonmalignant | 4 (17 %) |

| Preparative regimen | |

| Full intensity | 17 (71 %) |

| Reduced intensity | 11 (29 %) |

| Stem cell source | |

| Unrelated cord blood | 2 (8 %) |

| Bone marrow—unrelated adult donor | 2 (8 %) |

| Bone marrow—HLA-identical sibling | 5 (21 %) |

| Peripheral blood—unrelated adult donor | 7 (29 %) |

| Peripheral blood—HLA-identical sibling | 8 (33 %) |

| Prior acute GVHD grade II–IV | 13 (54 %) |

| Prior number of cGVHD therapies, median (range) | 3 (1–9) |

| On corticosteroids at time of interview | 22 (92 %) |

| Additional systemic cGVHD therapies used at the time or prior to interview | |

| Calcineurin inhibitor | 24 (100 %) |

| Mycophenolate Mofetil | 5 (21 %) |

| Pentostatin | 4 (17 %) |

| Extracorporeal photopheresis | 6 (25 %) |

| Azathioprine | 1 (4 %) |

| Infliximab | 3 (13 %) |

| Etanercept | 2 (8 %) |

| Median (range) platelet count at time of interview | 291,000 (83,000–790,000) |

| Median (range) bilirubin at time of interview | 0.7 (0.3–8.4) |

| Median Karnofsky/Lansky at time of interview | 90 % (50 %–100 %) |

| Median NIH Global score at time of interview | 5 (1–8) |

Table 2.

Chronic GVHD manifestations at time of interview

| Age 5–8 (n =8) | Age 9–12 (n =8) | Age 13–17 (n =8) | Total (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organ | NIH Score ≥1 | NIH Score ≥1 | NIH Score ≥1 | |

| Skin | 6/8 | 6/8 | 5/8 | 17/24 (71 %) |

| Eye | 1/8 | 7/8 | 3/8 | 11/24 (46 %) |

| Mouth | 2/8 | 2/8 | 6/8 | 10/24 (42 %) |

| GI | 3/8 | 3/8 | 3/8 | 9/24 (38 %) |

| Liver | 3/8 | 3/8 | 3/8 | 9/24 (38 %) |

| Lung | 1/8 | 3/8 | 3/8 | 7/24 (29 %) |

| Joint & fascia | 4/8 | 2/8 | 1/8 | 7/24 (29 %) |

| Genital | 0/2 | 0/3 | 0/3 | (0 %) |

Fig. 2.

cGVHD Manifestations at time of interview, using NIH 0–3 staging criteria, by organ (expressed as mean with standard deviation)

Symptoms by age groups

Table 3 details the patient and parent symptom reports. Differences between age groups are described below; however, given the small within-age sample size, there was insufficient power to detect statistically significant differences. Areas of worry were consistent throughout the child interviews regardless of age. Of those who reported “worrying a lot,” 57 % worried about their appearance, 29 % about not getting better, and 29 % about social concerns, including school attendance. Table 4 details the terms and phases that study participants used to describe their symptoms.

Table 3.

cGVHD symptom described during the interviews: distribution by age

| Age 5–8 (%) | Age 9–12 (%)

|

Age 13–17 (%)

|

Total (%)

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Location | Symptom | Parent report | Parent report | Child report | Parent report | Child report | Parent report | Child reporta |

| N =8 | N =8 | N =8 | N =8 | N =8 | N =24 | N =16 | ||

| Skin, nails and hair | Skin discoloration | 83 | 88 | 50 | 88 | 67 | 83 | 59 |

| Skin rash | 88 | 29 | 38 | 38 | 75 | 52 | 57 | |

| Nail peeling | 43 | 43 | 38 | 75 | 71 | 54 | 55 | |

| Thick skin | 71 | 33 | 0 | 43 | 0 | 49 | 0 | |

| Skin tightness | 17 | 38 | 13 | 17 | 0 | 24 | 7 | |

| Skin sores | 50 | 0 | 0 | 13 | 43 | 21 | 22 | |

| Skin pain: with touch | 38 | 13 | 0 | 14 | 38 | 22 | 19 | |

| Skin pain: when clothes rub | 25 | 25 | 13 | 0 | 29 | 17 | 21 | |

| Eyes | Eyes bothersome | 75 | 88 | 63 | 50 | 63 | 71 | 63 |

| Eyes dry | 38 | 71 | 75 | 63 | 50 | 57 | 63 | |

| Hard to see | 14 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 57 | 38 | 54 | |

| Eyes hurt | 0 | 43 | 50 | 25 | 14 | 23 | 32 | |

| Mouth | Mouth bothersome | 25 | 88 | 63 | 71 | 88 | 61 | 76 |

| Mouth pain | 14 | 50 | 50 | 71 | 63 | 45 | 58 | |

| Pain while eating | 29 | 43 | 25 | 50 | 29 | 41 | 27 | |

| Mouth dry | 25 | 25 | 50 | 17 | 38 | 22 | 44 | |

| Problems eating | 25 | 17 | 13 | 43 | 25 | 28 | 19 | |

| GI | Foods cannot/would not eat | 57 | 88 | 75 | 63 | 86 | 78 | 81 |

| Diarrhea | 71 | 50 | 38 | 63 | 50 | 61 | 44 | |

| Belly pain | 57 | 63 | 63 | 63 | 25 | 61 | 44 | |

| Poor appetite | 75 | 29 | 0 | 14 | 13 | 39 | 7 | |

| Difficulty swallowing | 29 | 25 | 0 | 38 | 13 | 31 | 7 | |

| Constipation | 0 | 17 | 13 | 0 | 25 | 6 | 19 | |

| Muscles and joints | Muscles/joints bothersome | 83 | 88 | 25 | 88 | 75 | 86 | 50 |

| Weak muscles | 80 | 100 | 50 | 71 | 86 | 84 | 68 | |

| Muscle cramping | 33 | 86 | 75 | 38 | 57 | 52 | 66 | |

| Tight joints | 67 | 83 | 50 | 71 | 57 | 52 | 54 | |

| Muscle pain | 50 | 57 | 38 | 63 | 29 | 57 | 24 | |

| Difficulty moving | 50 | 71 | 14 | 40 | 33 | 54 | 24 | |

| Unable to run | 38 | 43 | 13 | 57 | 50 | 46 | 32 | |

| Lungs | Short of breath: running | 43 | 67 | 86 | 100 | 100 | 70 | 93 |

| Short of breath: walking up stairs | 60 | 86 | 63 | 50 | 67 | 65 | 65 | |

| Short of breath | 38 | 63 | 63 | 71 | 50 | 57 | 57 | |

| Short of breath: walking few blocks | 33 | 43 | 50 | 25 | 43 | 34 | 47 | |

| Short of breath: walking few steps | 14 | 14 | 50 | 17 | 13 | 15 | 32 | |

| Coughing | 38 | 86 | 71 | 63 | 25 | 62 | 48 | |

| Breathing problems | 50 | 75 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 58 | 50 | |

| Fatigue | Easily fatigued | 63 | 63 | 63 | 100 | 29 | 75 | 46 |

| Tired: feel weak | 67 | 57 | 29 | 71 | 75 | 65 | 52 | |

| Tired: short of breath | 20 | 33 | 38 | 14 | 25 | 22 | 32 | |

| Social/emotional | Worry | 57 | 88 | 63 | 88 | 75 | 78 | 69 |

| Sad | 29 | 63 | 57 | 75 | 75 | 56 | 66 | |

| Lack friends | 29 | 38 | 13 | 0 | 0 | 22 | 7 | |

Total child numbers are lower than parents because 5–8 year olds did not respond to the questionnaire

Table 4.

Specific words and phrases used by children to describe GVHD symptoms

| Ages 5–8a | Ages 9–12 | Ages 13–17 | Quotes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skin | Bumps, swell up, hurts, raised up, wet, oozing, hot, poking, hard, rash, different | Itchy, dry, bumpy, red dots, spots, flaky, peeling, swollen, hurts, hot, tugging, black spots, scabbing | Bumpy, rough, tough, scabs, getting darker, red, sensitive, painful, discolored, scarring | “I can’t stop itching the bumps” (Age 11) “The bones inside me hurt. They push my skin” (Age 5) “It has a weird feeling to it” (Age 11) “When my dad would hug me, it would hurt” (Age 12) “When I brush against something it often turns bluish, purplish, and the skin may tear” (Age 14) |

| Nails | Peeling | Cracking, coming off, peeling | Thin, falling off, cracking | “My nails are open, they have little cracks. I don’t like that” (Age 12) “My toenails, they are sort of flat. I don’t know how they can be dryer.” (Age 14) |

| Hair | Itchy | Thin, coming out | Thin, falling out, embarrassing | “It gets flaky and dry, kind of flakes off” (Age 11) |

| Mouth | Dry, need to drink a lot of water, hurts to eat spicy food, burning, stinging | Burning, dry, thirsty, sores, avoid hot/sour/spicy foods, white bumps under tongue, hurts to swallow | “It’s like I’m thirsty all the time” (Age 17) “Pills. Like if I don’t wash them down all the way, it kind of just gets stuck.” (Age 11) “My mouth and the inside of my cheeks – it gets really sensitive when I eat certain foods or drink certain drinks” (Age 16) |

|

| Eyes | Dry, feel like you need to rub them, scratchy, burning, blurry, puffy, painful | Dry, blurry, burning and pain in the eyes | “They’re really, like, scratchy and you sometimes, you can’t, like, make stuff out, like, it makes it blurry sometimes.” (Age 11) “It’s just like these little walls that if I scratch or open my eyes or close really hard or something, they’ll just come off.” (Age 13) “Sometimes I get blurry vision and I can’t read or see.” (Age 12) “Cloudy sight bothered me the most. Now the pain” (Age 14) |

|

| Lungs | Out of breath, need air | Breathing really fast, cannot breathe | Side hurts, cannot breathe after running, have to stop to catch a breath, tickle in throat | “I got like short of breath very quickly. I couldn’t walk up the stairs, I couldn’t breathe. Even when I was sitting down, I could feel my heart beating very quickly.” (Age 11) “I can’t go anywhere by myself. Going to the bathroom it makes me get out of breath or something like that.” (Age 6) |

| Stomach | Running to the bathroom | Noisy, growling stomach, cramping | Do not feel like eating, cramping | “(My cells) started taking my organs and they’re having a war in there. My stomach growls.” (Age 12) “Sometimes when I have stomach aches I feel as if sometimes it’s pulling on me. I feel something like throbbing in the stomach.” (Age 14) |

| Muscles | Tired | Hands get stuck, feel like sitting down, crampy, hard to jump, knots | Hard to walk, cramping, feeling weak, hands get stuck in a position, tingling, contractions | “It’s like I can’t move my feet no more. I can’t take another step.” (Age 12) “It’s hard to walk.” (Age 17) “They feel like I didn’t use it [legs] for a long time.” (Age 15) “When I walk, my arms and legs hurt.” (Age 14) |

| Joints | Tight, poking | Tough to bend, knots, tight | Stiff, tight | “They’re just, like, tight. They’re like knots almost, like it feels like a knot. If you’re holding stuff, I’m holding something too long, my hands just cramp up in that position and then I have to push them back like that and it goes back to normal.” (Age 11) “I noticed that my hand or something might get stuck if I write or something and they all of a sudden might get stuck in one place and I can’t move it or I might just be lying there and my fingers might get stuck.” (Age 15) “I can’t stretch out my knees properly.” (Age 14) |

| Vagina | Pain, stings | “It stings” (Age 6) “I used to have pain going to the bathroom.” (Age 15) |

||

| Fatigue | Tired, interferes with normal activity level, cannot participate in sports | Tired, cannot keep up | “I just don’t have any energy.” (Age 12) “My fatigue – it kind of affects my life a lot more like with I’m not able to do what I always want to do.” (Age 11) |

|

| Appearance | Cannot be normal | People talk about it, do not like how it looks | Embarrassing, look fat | “I don’t like these red dots. Some people look at me funny, yeah, and that bothers me.” (Age 11) “I want to grow.” (Age 14) “I don’t like the color around my eyes.” (Age 12) “My teeth have been destroyed. They say from dry mouth.” (Age 14) “My face was just -it was puffy, I could hardly see, my mouth was messed up, I was just messed up. Now I worry because my face because I’m getting a mustache, again I got this acne and my cheeks are huge.” (Age 15) |

Given the young age of these children, they were not interviewed independently. Therefore, parent responses are reported to demonstrate what words parents say their child uses to describe symptoms

Ages 5–8

Children ages 5–7 years were interviewed together with a parent. Within this age group, the most common reported skin manifestations were rash (88 %), discoloration (83 %), and thick skin (71 %). Seventy-five percent of the parents interviewed reported that their child’s eyes “bothered them” (predominately due to dryness [38 %]), 71 % reported that their child was bothered by diarrhea, and 75 % indicated their child was experiencing poor appetite. Muscle and joint problems were also frequent (83 %), with the most common concern being muscle weakness (80 %).

Ages 9–12

There were high rates of symptom reports in each of the eight domains explored in this age group. Eyes were commonly reported as symptomatic by patients and parents (63 and 88 %, respectively), with 75 % of children specifying eye dryness and half of children reporting eye pain and difficulty seeing. Skin discoloration was the most common skin symptom reported (children 50 %, parents 88 %) and many children reported mouth problems (63 %) and avoiding certain foods (children 75 %, parents 88 %). Many children reported worrying a lot (63 %); however, comparatively fewer participants indicated that they lacked friends (13 %).

The symptoms with the highest concordance (100 %) between parent and child were skin sores, nail peeling, problems eating, fatigue, overall shortness of breath, and constipation. Symptoms with the least concordance were eye dryness (43 %), bothersome muscles and/or joints (38 %), and shortness of breath while running (40 %).

Ages 13–17

As with the 9–12 year olds, skin discoloration was a commonly reported symptom (children 67 %, parents 88 %). Eye problems were similarly reported as bothersome by patients in this age group, but “dry eyes” were less problematic. Also commonly endorsed were nail peeling, mouth problems, bothersome muscles and joints, weak muscles, and shortness of breath when running. Seventy-five percent of children endorsed feelings of sadness and worry. None endorsed having a lack of friends.

The symptoms with the highest concordance (100 %) between parent and child were poor appetite, shortness of breath within a few steps, shortness of breath when running, and concerns about a lack of friends. Symptoms with the least amount of concordance were fatiguability (children 33 %, parent 100 %), muscle pain (children 29 %, parent 63 %), and skin rashes (children 75 %, parent 38 %).

Discussion

Assessment of symptoms associated with cGVHD in children can provide useful information about current health status, distinguish children with differing levels of cGVHD severity and resultant morbidity, identify individuals who warrant clinical intervention for symptom distress, and improve our understanding of the impact of cGVHD on functioning and lifestyle from the child/adolescent’s perspective. This study explored the experience of cGVHD symptom distress among children, with an emphasis on comparing the specific language used by children to describe their cGVHD symptoms and their comprehension of symptom concepts across the developmental spectrum. The study also identified more comprehensive and specific descriptions of cGVHD symptoms than would be obtained using generic health-related quality of life or symptom scales. Specifically, we found that pediatric patients over 9 years of age can identify and report organ-specific symptoms. Common language emerged to reflect these symptoms (for example, “skin bumpy,” “mouth burning,” “white bumps that you can’t pop in the mouth,” “tickle in the throat”). Overall concordance between patient and parent report for the 9–12 and 13–17 age groups was moderate and perhaps surprisingly, the distribution of high or low concordance was approximately equal across more subjective symptoms (such as fatigue, or muscle pain) and what would be considered more objective symptoms, like skin rash. No consistent pattern of child under- or over-reporting in comparison to the parent report was observed.

When comparing patient symptom reports to the clinician-rated NIH organ scores, which are based on a combination of subjective and objective criteria, we observed higher symptom reporting by patients and parents compared with clinician rating of the severity of cGVHD organ involvement in almost all categories. For example, only 46 % of patients had an NIH eye score ≥1, but “eye bother” was endorsed by 63 % of patients in the 9–12 and 13–17 age groups and by 75 % of the parent–child dyads in the 5–8-year-old age group. This observation is consistent with the findings of other investigators, and the reasons are likely multifactorial. Children and their parent were reporting the symptoms that caused the child bother or distress, whereas clinicians were scoring cGVHD severity using a combination of disease signs and symptoms. Other factors which may have contributed to observing only partial concordance between clinician cGVHD severity rating and patient-reported symptoms include medication side effects, the long-term sequelae of prior treatment, and limitations in performing clinical assessments for cGVHD severity in younger children (e.g., inability to perform Schirmer’s test, pulmonary functions tests, etc.). A number of studies in adults have shown that patient and clinician ratings are only partially concordant, and our results provide additional evidence to suggest that self-report may complement rather than duplicate clinician-reported outcome measures in cGVHD [25, 26].

While the inclusion of pediatric patients across the age spectrum and the multi-institutional design were strengths of the study, a few limitations should be noted. As this was the initial study to obtain both parent and patient data in an exploratory fashion, our sample size was relatively small. It was reassuring however, that saturation was reached in each of the age groups studied, suggesting that the sample size was adequate for the study. One factor that can limit accuracy in qualitative interviews and recall studies with youth is the recency effect. That is, typically, recent symptoms will be recalled, especially those that might have occurred in the past 24 h. Prompts were needed for younger children to report using a recall period that extended beyond the past day. Inclusion of the parent in the interview of 5–7 year olds was also designed to mitigate possible recency effects. Lastly, some of the signs and symptoms that were reported by patients and their parents are experienced in HSCT recipients without cGVHD, or may represent adverse effects of cGVHD therapies (e.g., muscle weakness, stretch marks and weight gain caused by corticosteroids). Future studies are needed to explore the prevalence and severity of symptoms comparing HSCT recipients with and those without cGVHD.

Next steps

Our findings can be applied towards the development of a pediatric GVHD symptom scale. There exists no generic or cancer-specific pediatric symptom measure that captures the full range of symptoms described in the qualitative interviews. As expected, the global domains within which cGVHD symptoms can be grouped (e.g., lung, skin, etc.) did not differ from the Lee Scale; however, across the three age groups studied, children used different vocabulary across to describe many of their symptoms. A pediatric scale must use developmentally appropriate symptom constructs and phrasing in order to be well understood by respondents of varying ages.

There remains a fundamental role for parent proxy report in pediatric clinical trials and health services research, particularly when children are unable to provide self-report. Even when children are able to self-report, parent proxy report should be considered as a secondary outcome measure given parents’ expanding role in clinical decision making and home treatment regimens for pediatric chronic health conditions [27]. Ideally, parent and child HRQOL instruments should measure the same constructs with parallel items in order to make comparisons between self and proxy report more meaningful [28, 29].

The study group is currently using the data derived from the qualitative interviews to generate a pool of items that will ultimately comprise a pediatric cGVHD symptom scale. All items will inquire about symptoms that have bothered the child in the last week, the severity of the symptom, and whether the symptom interfered with the child’s usual daily activities. Two forms will be developed: a child self-report and also a corresponding parent report of the child’s symptoms. FDA guidelines recommend that instrument development for children and adolescents be conducted within fairly narrow age groupings [30]. After the items have had preliminary pilot testing, cognitive interviewing within the age groupings specified for this study will be conducted to refine the symptom items and the response choices to ensure their comprehension by children and adolescents across the developmental spectrum. Following this, a quantitative psychometric validation study will be conducted.

PRO measures are increasingly used in studies evaluating new therapies in order to provide a more comprehensive picture of treatment effects. Our research efforts represent an important and timely step in the development of an age-appropriate outcome measure for cGVHD symptoms, toward the longer-range objective of enhancing response assessment in clinical trials of new therapies for children with cGVHD.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the support of several individuals who helped make this work possible. We thank Lauren Latella, BS, Nia Billings, MA, and Sima Zadeh, MA who helped with the coding of the data and Stephanie Lee, MD who gave significant input and advice in developing this protocol. We thank Colleen Schaefer, BS, CRC and Meredith Marshall, MA, CRC who performed a number of the interviews and Haven Battles, PhD who calculated the Intra-class Correlation Coefficients. We especially thank the patients and their parents who so openly shared their experiences of living with chronic GVHD and how these symptoms impact their lives.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to report. The authors have full control of all primary data and agree to allow the journal to review our data, if requested.

Contributor Information

Lori Wiener, Pediatric Oncology Branch, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, 10 Center Drive, Bethesda, MD 20892, USA.

Kristin Baird, Pediatric Oncology Branch, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, 10 Center Drive, Bethesda, MD 20892, USA.

Caroline Crum, Pediatric Oncology Branch, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, 10 Center Drive, Bethesda, MD 20892, USA.

Kimberly Powers, Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA.

Paul Carpenter, Clinical Research Division, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, and Seattle Children’s Hospital, Seattle, WA, USA.

K. Scott Baker, Clinical Research Division, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, and Seattle Children’s Hospital, Seattle, WA, USA.

Margaret L. MacMillan, Blood and Marrow Transplant Program and Amplatz Children’s Hospital, Department of Pediatrics, University of Minnesota Medical School, Minneapolis, MN, USA

Eneida Nemecek, Doernbecher Children’s Hospital, Oregon Health & Science University Portland, Portland, OR, USA.

Jin-Shei Lai, Department of Medical Social Sciences and Pediatrics, Northwestern University, Chicago, IL, USA.

Sandra A. Mitchell, Outcomes Research Branch, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA

David A. Jacobsohn, Children’s National Medical Center, Washington, DC, USA

References

- 1.Jacobsohn DA, Arora M, Klein JP, et al. Risk factors associated with increased nonrelapse mortality and with poor overall survival in children with chronic graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 2011;118(16):4472–4479. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-04-349068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vogelsang GB, Wagner JE. Graft-versus-host disease. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 1990;4:625–639. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferrara JL, Deeg HJ. Graft-versus-host disease. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:667–674. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199103073241005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zecca M, Prete A, Rondelli R, et al. Chronic graft-versus-host disease in children: incidence, risk factors, and impact on outcome. Blood. 2002;100:1192–1200. doi: 10.1182/blood-2001-11-0059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shulman HM, Sullivan KM, Weiden PL, et al. Chronic graft-versus-host syndrome in man. A long-term clinicopathologic study of 20 Seattle patients. Am J Med. 1980;69:204–217. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(80)90380-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sullivan KM, Shulman HM, Storb R, et al. Chronic graft-versus-host disease in 52 patients: adverse natural course and successful treatment with combination immunosuppression. Blood. 1981;57:267–276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Filipovich AH, Weisdorf D, Pavletic S, et al. National institutes of health consensus development project on criteria for clinical trials in chronic graft-versus-host disease: I. Diagnosis and staging working group report. Biol Blood Marrow Transpl. 2005;11(12):945–956. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2005.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pavletic SZ, Martin P, Lee SJ, et al. Measuring therapeutic response in chronic graft-versus-host disease: national institutes of health consensus development project on criteria for clinical trials in chronic graft-versus-host disease: IV. Response criteria working group report. Biol Blood Marrow Transpl. 2006;12:252–266. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2006.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jacobsohn DA, Kurland BF, Pidala J, et al. Correlation between NIH composite skin score, patient reported skin score and outcome: results from the chronic GVHD consortium. Blood. 2012;120(13):2545–2552. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-04-424135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arai S, Jagasia M, Storer B, et al. Global and organ-specific chronic graft-versus-host disease severity according to the 2005 NIH Consensus Criteria. Blood. 2011;118:4242–4249. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-03-344390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Drotor D. Measuring health related quality of life in children and adolescents: implications for research and practice. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; New Jersey: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Varni JW, Sherman SA, Burwinkle TM, Dickinson PE, Dixon P. The PedsQL family impact module: preliminary reliability and validity. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2004;2:55. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-2-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bhatia S, Jenney ME, Bogue MK, et al. The Minneapolis–Manchester quality of life instrument: reliability and validity of the adolescent form. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:4692–4698. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.05.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bhatia S, Jenney ME, Wu E, et al. The Minneapolis–Manchester quality of life instrument: reliability and validity of the youth form. J Pediatr. 2004;145:39–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Parsons SK, Shih MC, Mayer DK, et al. Preliminary psychometric evaluation of the child health ratings inventory (CHRIs) and disease-specific impairment inventory-hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (DSII-HSCT) in parents and children. Qual Life Res. 2005;14:1613–1625. doi: 10.1007/s11136-005-1004-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Parsons SK, Shih MC, Duhamel KN, et al. Original research article: maternal perspectives on children’s health-related quality of life during the first year after pediatric hematopoietic stem cell transplant. J Pediatr Psychol. 2006;10:1100–1115. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsj078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee S, Cook EF, Soiffer R, Antin JH. Development and validation of a scale to measure symptoms of chronic graft-versus-host disease. Biol Blood Marrow Transpl. 2002;8:444–452. doi: 10.1053/bbmt.2002.v8.pm12234170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Inamoto Y, Martin PJ, Chai X, et al. Clinical benefit of response in chronic graft-versus-host disease. Biol Blood Marrow Transpl. 2012;18(10):1517–1524. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2012.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patrick DL, Burke LB, Gwaltney CJ, et al. Content validity-establishing and reporting the evidence in newly developed patient-reported outcomes (PRO) instruments for medical product evaluation: ISPOR PRO good research practices task force report: part 1-eliciting concepts for a New PRO instrument. Value in Health. 2011;14(8):967–977. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2011.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matza LS, Patrick D, Riley AW, Alexander JJ, Rajmil L, Pleil AM, Bullinger M. Pediatric patient-reported outcome instruments for research to support medical product labeling: report of the ISPOR PRO Good Research Practices for the Assessment of Children and Adolescents Task Force. Value Health. 2013;16:461–479. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2013.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.DeMuro CJ, Lewis SA, DiBenedetti DB, Price MA, Fehnel SE. Successful implementation of cognitive interviews in special populations. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2012;12(2):181–187. doi: 10.1586/erp.11.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brod M, Tesler LE, Christensen TL. Qualitative research and content validity: developing best practices based on science and experience. Qual Life Res. 2009;18:1263–1278. doi: 10.1007/s11136-009-9540-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mays N, Pope C. Qualitative research in health care: assessing quality in qualitative research. Br Med J. 2000;320(7226):50. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7226.50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guest G, Bunce A, Johnson L. How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Method. 2006;18(1):59–82. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xiao C, Polomano R, Bruner DW. Comparison between patient-reported and clinician-observed symptoms in oncology. Cancer Nurs. 2012 doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e318269040f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mitchell SA, Leidy NK, Mooney KH, et al. Determinants of functional performance in long-term survivors of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation with chronic graft-versus-host disease (cGVHD) Bone Marrow Transpl. 2010;45(4):762–769. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2009.238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Varni JW, Burwinkle TM, Katz ER, Meeske K, Dickinson P. The PedsQL in pediatric cancer: reliability and validity of the pediatric quality of life inventory generic core scales. Multidim Fatigue Scale Cancer Module Cancer. 2002;94:2090–2106. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cremeens J, Eiser C, Blades M. Characteristics of health-related self-report measures for children aged three to eight years: a review of the literature. Qual Life Res. 2006;15:739–754. doi: 10.1007/s11136-005-4184-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Russell KMW, Hudson M, Long A, Phipps S. Assessment of health-related quality of life in children with cancer: consistency and agreement between parent and child reports. Cancer. 2006;106:2267–2274. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.FDA. Guidance for Industry: Patient-reported outcome measures: Use in medical product development to support labeling claims. Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, Food and Drug Administration; MD: 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]