Abstract

Purpose

In current fiscally constrained health care systems, the transition of cancer survivors to primary care from tertiary care settings is becoming more common and necessary. The purpose of our study was to explore the experiences of survivors who are transitioning from tertiary to primary care.

Methods

One focus group and ten individual telephone interviews were conducted. Data saturation was reached with 13 participants. All sessions were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim, and analyzed using a qualitative descriptive approach.

Results

Eight categories relating to the main content category of transition readiness were identified in the analysis. Several factors affected participant transition readiness: how the transition was introduced, perceived continuity of care, support from health care providers, clarity of the timeline throughout the transition, and desire for a “roadmap.” Although all participants spoke about the effect of their relationships with health care providers (tertiary, transition, and primary care), their relationship with the primary care provider had the most influence on their transition readiness.

Conclusions

Our study provided insights into survivor experiences during the transition to primary care. Transition readiness of survivors is affected by many factors, with their relationship with the primary care provider being particularly influential. Understanding transition readiness from the survivor perspective could prove useful in ensuring patient-centred care as transitions from tertiary to primary care become commonplace.

Keywords: Primary care, transitions in care, patient-centred care, qualitative research, survivors

BACKGROUND

In 2005, the U.S. Institute of Medicine highlighted the importance of the transition from active treatment to post-treatment care for a growing population of adult cancer survivors1. Although several models of survivorship care2–4 have been developed to facilitate the transition, those models are heterogeneous and can result in variations in the quality of care5. More than 10 years after the Institute of Medicine report, many survivors and health care professionals remain “lost in transition,” and an urgent need for high-quality survivorship care and patient-centred transitions remains5,6.

The need for high-quality survivorship care is accentuated by the unsustainability of current practices in light of an increasing cancer incidence driven by an aging and growing population7. Traditionally, most survivorship care is performed by oncologists, resulting in many healthy patients receiving specialized care in tertiary settings8. Because of the shrinking oncology workforce relative to the growing demand for cancer care, the current practice raises concerns about the quality of care for cancer survivors and patients alike8–10.

Primary care is a promising setting for sustainable survivorship care provision11. Randomized trials12,13 and retrospective studies14,15 have reported that survivors can be effectively and safely cared for in a primary setting. Another trial reported increased patient satisfaction with follow-up in primary care16. Furthermore, as more time elapses from the initial diagnosis, survivors tend to receive care from their primary care physician (pcp) regardless of whether they were formally transitioned after acute cancer treatment17. Those frequent encounters present an opportunity for effective survivorship care for survivors, many of whom are elderly and have comorbid conditions that are best addressed in a primary care setting18,19. Many survivorship models have yet to tap into the potential of pcps to assume exclusive care for cancer survivors despite the willingness of those providers to undertake that responsibility if given appropriate information and support8.

In response, the Transition Care Clinic (tcc) was implemented in 2014 in the Odette Cancer Centre with the goal of improving the quality and patient-centredness of care for cancer survivors. The tcc facilitates the transition of healthy cancer survivors who have completed curative treatment at the Odette Cancer Centre to pcps in their communities. The clinic was designed as a nurse practitioner–operated clinic to provide patients with high-quality survivorship care and a patient-centred transition from tertiary to primary care. Survivor transitions to primary care are made feasible by Canada’s publicly funded health care system, which ensures the provision of survivorship care regardless of setting. An initial pilot population of colorectal cancer and lymphoma survivors were chosen because of their relatively well-identified survivorship and care coordination needs20,21. The tcc applies the most recent evidence-based guidelines and best practices identified by group consensus at the Odette Cancer Centre, such as the provision of treatment summaries and survivorship care plans (scps)3. At the time of writing, 105 individuals from among 131 cancer survivors referred to the tcc were successfully transitioned to their pcp.

By curtailing unnecessary reliance on scarce specialized services, the tcc and similar models of survivor-ship care have the potential to improve care for cancer survivors and patients alike. However, an exploration of the patient-centredness of transitions to primary care is warranted because we anticipate that the tcc and similar models of survivorship care will become more common in response to increasing demand for specialized care. It is imperative to engage patients and to consider their values in the design of interventions during this important transition of care.

The Institute of Medicine defines patient-centred care as “respectful of and responsive to individual patient preferences, needs, and values and ensuring that patient values guide all clinical decisions”22 (p. 6). There have been calls by leaders in survivorship research to address the paucity of evidence about patient-centred transitions in survivorship care, but large gaps in the literature remain23,24. Previous studies24–29 have explored the experiences of survivors with pcp-delivered survivorship care, but none have examined the transition to the pcp. It is imperative to address that knowledge gap because it is well recognized that transitions in care for cancer survivors often have negative implications1.

The objective of the present study was to use an exploration of the experiences of survivors as they transition from tertiary care to their pcps to understand the effects of the tcc on patient-centred care.

METHODS

The team conducted a focus group and semi-structured individual telephone interviews with consenting participants until data saturation was achieved. A qualitative descriptive approach was used to guide the creation of the focus group and interview guides, and the analysis of the transcripts30. That approach was consistent with our objective in two ways. First, it allowed us to focus on and summarize the content of participant experiences. Second, qualitative description provided a practical approach to investigate how the survivor experiences compared with other transitions in care research.

Setting

The Odette Cancer Centre is one of the largest cancer centres in Canada and North America. The Odette Cancer Centre is situated in the Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, a large academic teaching hospital in Toronto, Ontario. All patients are treated under the publicly funded and administered Ontario Hospital Insurance Plan and face no direct costs for health care delivery.

Participants

Participating survivors were recruited from the tcc. All participants had completed treatment at the Odette Cancer Centre, had been referred to the tcc by their physician, were more than 18 years of age, and were fluent in English. To obtain broad insight into the transition to primary care, we strived for maximum variation in sampling: participants included gastrointestinal cancer and lymphoma survivors who were referred to, but might not have already been seen in, the tcc31. Participants consented to the study and were provided with information about the focus group session or, in the latter portion of the study, a telephone interview. Demographic and treatment characteristics (age, sex, cancer diagnosis, treatments received, and time since last treatment) were recorded.

Focus Group and Interviews

The focus group and interviews followed a semi-structured guide (Table i). The guide was designed to facilitate free-flowing conversations and discussions, and thus consisted of open-ended questions. Depending on the responsiveness of participants, not all questions were necessarily asked during the focus group session or the telephone interviews.

TABLE I.

Focus group and interview guide

| 1. | Please describe your experiences moving from being cared for here at the Odette Cancer Centre to being cared for by your family doctor. |

| 2. | What kinds of concerns did you have? |

| 3. | How were these concerns addressed by your health care team? |

| 4. | What kind of advice would you provide someone who is about to go through this step in their journey? |

| 5. | What do you think could have been done better to improve your experience? |

| 6. | What kinds of things happened during this period that improved your experience? |

| 7. | If you could imagine an ideal life after cancer, and while receiving follow-up care from your family doctor, what would it include? |

| 8. | Is there anything else you would like to suggest and/or any other comments you would like to make before we end our time together? |

The focus group session was conducted with 3 participants in June 2014. After the 1st session, difficulties were encountered in accruing participants because of unwillingness on the part of the survivors to return to the Odette Cancer Centre for the sole purpose of the study. For the convenience of participants, the methods were revised to facilitate one-on-one telephone interviews with participants instead of focus groups. The focus group session and all interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Analysis

Transcripts were read simultaneously with audio-recordings to ensure accuracy. Data analysis occurred concurrently with data collection. Before data analysis, all transcripts were read by the investigators to obtain an overall impression of the content. A qualitative description approach was used for the analysis30. We enhanced the rigour of that analytic approach by applying these strategies31:

■ Authenticity (allowing survivors to speak freely for accurate representation of their experiences)

■ Credibility (attention to context to ensure that the insider perspectives of survivors are captured)

■ Criticality (appraisal of each decision made during the research process)

■ Integrity (researcher triangulation)

All meaningful text was identified and coded as the audio-recordings were transcribed. No analytic framework was imposed a priori, allowing for the data-driven evolution of identified content categories32. During the analysis and coding of the focus group session, 22 initial categories were identified. Those categories were applied and simultaneously evaluated for each transcription. Researchers achieved consensus in stages throughout the study as the codes and categories evolved. Participant characteristics were descriptively analyzed using the SAS software application (version 9.4: SAS Institute, Cary, NC, U.S.A.).

RESULTS

Between May and December 2014, about 37 potential participants were invited by a member of their health care team to participate in the study. From June to December 2014, 13 survivors participated in the study: 3 took part in the focus group, and 10, in the individual interviews. The team agreed that data saturation was accomplished after 13 participants because new ideas were no longer being explored.

Table ii summarizes the characteristics of the participants in the study. Mean age was 51.2 ± 18 years, and about two thirds of the participants were women (n = 9). Of the 13 participants, 9 (69%) had already been seen in the tcc. Mean time elapsed since the last treatment for those participants was 41 ± 22 months. From 2008 to 2013, 7 participants had been diagnosed with lymphoma, and 5, with a type of gastrointestinal cancer; information was unavailable for 1 participant. All participants for whom treatment information was available had received chemotherapy.

TABLE II.

Characteristics of participating survivors

| Participation type | Age (years) | Sex | Year of diagnosis | Initial diagnosis | Treatments received | Time since last treatment (months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Focus group | 26 | Female | 2010 | Nodular sclerosing Hodgkin lymphoma | Chemotherapy, radiation | 38 |

| Focus group | 55 | Male | 2012 | Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma | Chemotherapy | 15 |

| Focus group | 31 | Female | 2011 | Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma | Chemotherapy, radiation | 30 |

| Interview 1 | 53 | Male | — | — | — | — |

| Interview 2 | 80 | Female | 2011 | Rectal cancer | Chemotherapy, radiation, surgery | 34 |

| Interview 3 | 30 | Female | 2010 | Hodgkin lymphoma, borderline bulky | Chemotherapy | 47 |

| Interview 4 | 67 | Male | 2011 | Adenocarcinoma cecum | Chemotherapy, surgery | 27 |

| Interview 5 | 54 | Female | 2009 | Rectal cancer | Chemotherapy, radiation, surgery | 58 |

| Interview 6 | 76 | Female | 2013 | Rectosigmoid cancer | Chemotherapy, radiation, surgery | 4 |

| Interview 7 | 37 | Male | 2009 | Nodular sclerosing Hodgkin lymphoma | Chemotherapy, radiation | 61 |

| Interview 8 | 61 | Female | 2008 | Rectal cancer | Chemotherapy radiation, surgery | 72 |

| Interview 9 | 44 | Female | 2008 | Nodular sclerosing Hodgkin lymphoma | Chemotherapy, radiation | 70 |

| Interview 10 | — | Male | — | Lymphoma (unspecified) | — | — |

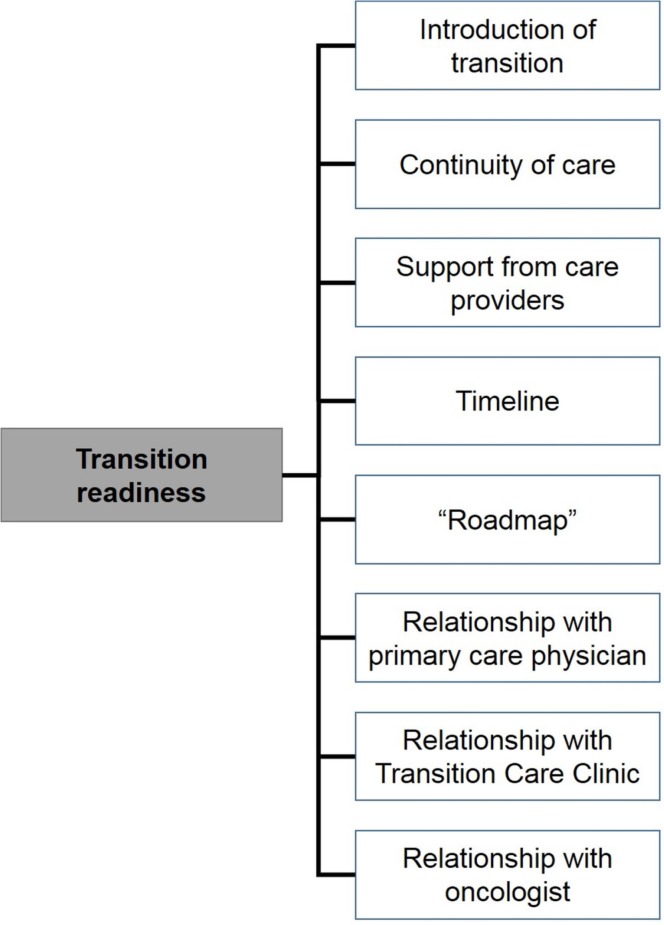

After grouping relevant codes together, the main category of “transition readiness” emerged, with 8 subcategories identified as factors that affect the experience of transition to the pcp (Figure 1). Of the 8 subcategories, 3 related to participant relationships with their health care providers. Table iii presents illustrative participant quotes for each subcategory.

FIGURE 1.

The main category of transition readiness consisted of 8 subcategories. Subcategories were identified during the analysis of a focus group session and semi-structured interviews with participating cancer survivors about their experiences during the transition from tertiary to primary care.

TABLE III.

Illustrative quotes from participating survivors, by subcategory of transition readiness

| Subcategory | Quote |

|---|---|

| Introduction of transition | They had already forewarned me. When I spoke to [my surgeon] about a month ago, he already told me what was going to happen—so, not at all a surprise. I am more than happy to be moved on to a PCP. — Interview participant 8 |

| Then suddenly you’re being transitioned out by someone who has never been a part of stuff. I think that would make people more worried. Why is this stranger telling me that I’m not coming back here anymore? — Interview participant 9 | |

| Continuity of care | I am pretty sure my family doctor has all [my information and required appointments]. The thing is, does my family doctor have the time to read this? — Interview participant 4 |

| Support from health care providers | I have concern for [cancer recurrence] for sure. I think every cancer survivor has that concern, but that’s where I say that chart with all of the symptoms to look out for and what to do when you have those symptoms and for the most part I am pretty happy with how that is dealt with because [the nurse practitioner] said if anything, contact the hospital or contact herself, in which case I will immediately. I understand that. — Interview participant 7 |

| Clarity of the timeline | [The nurse practitioner] had a plan of what needs to be done in the next 5 years, what needs to be done ongoing, what needs to be done when I turn 50, you know, things like that. — Interview participant 9 |

| I’ve had my next appointment given to me after the last one next year. Well, I don’t have that one now. So, who gives me that appointment? — Interview participant 2 | |

| Desire for a “roadmap” | Because we are not provided with a roadmap of anything. We are just told, we are handing you back to your family doctor. — Interview participant 7 |

| Relationship with the primary care physician | I just don’t know what a family physician is going to do; they’re so busy with so many patients. Another issue is “Are they going to be up on what I need?” So, I do have that concern—especially when I haven’t known this [PCP] before. — Interview participant 2 |

| Relationship with the Transition Care Clinic | Well for one thing, the nurse practitioner was very prepared. She had a whole transition plan printed out for me. And she’s going to send one to me and one to my family doctor. She went over it with me. And so, it wasn’t just like, “I’m going to take the photocopy out of the drawer, and I’m just going to take off things and write stuff.” And you know, she really ... she did ask me questions about stuff, but she also knew a lot about my situation already. And I also know that she works with [Dr. X], so she knows my principal oncologist and knows his patients’ stuff.... So that seemed really good. Also, she was just ... she was very thorough. — Interview participant 9 |

| Relationship with the oncologist | The hospital is still there for you if you need it. I mean, look at it as a good thing. Really, you no longer have to [be cared for] by the hospital, and there are other people that need that care. — Interview participant 3 |

PCP = primary care physician.

Transition Readiness

Our analysis revealed several important factors affecting the transition readiness of participants:

■ How the transition was introduced

■ Participant perception of the continuity of care

■ Support from health care providers

■ Clarity of the timeline throughout the transition

■ Utilization of a transition tool or roadmap

■ Relationships with health care providers (from the tcc, and from tertiary and primary care)

Introduction of the Transition

Some participants found that their health care provider was proficient in gradually introducing them to the transition period. The formalization of the introduction of the transition by referral to the tcc allowed participants to “brace” [participating survivor (PS) 9] for the process.

The thing is that because after they tell me “This is it, I’ll make you an appointment with the transition clinic; do you know what they do and stuff?” there was no surprise element out of it.

— PS 9

The survivors who were introduced to the transition by a member of their care team with whom they did not have an established relationship were less welcoming to the transition, and the abruptness of the introduction to the transition left some participants unsure about what to expect.

[“Transition” was] just kind of spun onto me. The oncologist didn’t explain it.... I was kind of left wondering. It seems ridiculous to go through all that I’ve been [through] and say, “Okay you don’t need any more check-up.”

— PS 2

Continuity of Care

Participants were reassured to know that information needed for their care had been passed on to and would be appropriately addressed by their pcp. That reassurance was augmented by receipt of a scp.

She had a whole (kind of) transition plan printed out for me. And she’s going to send one to me and one to my family doctor. She went over it with me. And so, it wasn’t just like, “I’m going to take the photocopy out of the drawer and I’m just going to [be] taking off things and writing stuff.”

— PS 9

Others are “hoping that the [quality of] care will be the same” (PS 1) as that provided in the Odette Cancer Centre, with the particular fear of “falling through the cracks” (PS 4). Specifically, some participating survivors were concerned that their pcp might not have time to provide the best care for them.

Support from Health Care Providers

Participants benefited from support from their health care providers throughout the transition process. The tcc helped to alleviate some psychosocial issues that might stem from the transition process. Some suggested that the clinic and its components, such as scps, provided ample support.

My main question or concern was, now that I am discharged ... what if, god forbid, something happens? [The nurse practitioner] said I don’t have to worry about that because she said if I call her, she can get me in to see [the oncologist] in one day.

— PS 5

Participant experiences suggested that their pcp played a major role in supporting them during the transition.

When we saw our family doctor[, he] said, “Okay, I got this note from your oncologist today saying this and this happened.”

— Focus group participant [FP]

[My pcp] said to me [that] from now on he’s going to find when to do the ct scans and whatever, and I said, “Fine, I trust you.” So he is going to do everything he can to keep me healthy and happy.

— PS 5

Clarity of the Timeline

Participants indicated the desire to know that the appropriate appointments and tests would be scheduled and completed after their transition; they needed someone to tell them “what to expect” (PS 2). Others described how, to accomplish that, they will now have to advocate for themselves.

I think that it is going to be up to me to remember the dates and that is how [my pcp] will know.

— PS 4

And I just want to know that I’m still in some kind of plan—going through what I’ve been through—and that I’ll just be followed up for the rest of my life.

— PS 2

The tcc, specifically the appointment with the nurse practitioner and the provision of a scp, helped to solidify the timeline for some participants. Others were worried that their “follow-up appointments and tests won’t get done” (PS 9) as they had before. It was also unclear to some by whom the appointments and tests would be arranged.

Desire for a Roadmap

In many cases, participants felt that a supplemental physical resource, such as a “roadmap” (FP and PS 7), would greatly improve their confidence during the transition. That resource should be as conspicuous as possible, in that it will contain all necessary information such as symptoms of recurrence, contact information for health care providers for specific concerns, and dates of future appointments and tests.

These [roadmaps] are things I’m thinking that ... your cancer survivors (the ones that are transitioning) would actually think, “Huh, they’re really thinking about this. They’ve got a plan. Even though they’re done with me, they’ve given me a way of monitoring myself so that I could remember (a reminder for myself).”

— PS 7

The scps often served as the main physical resource for information during the transition, but participants felt that the plans lacked conciseness, which hindered their usability.

Nobody reads 10 pages—a 1-page chart would be a very good idea.

— PS 7

Relationship with the PCP

Although all participants spoke of relationships with their health care providers, their relationship with the pcp most notably influenced the transition experience. In particular, well-established and trusting relationships between participants and pcps resulted in a positive transition experience.

We have a good relationship where [my pcp] is watching me. He’s not just giving me a prescription for a happy pill and saying “See you in a year.” And that’s what I call a good [pcp] that I am confident in and he won’t let this stuff go away.

— PS 8

One participant indicated that all he needed during transition was to “know that [the primary care] doctor has time for [him]” (PS 4). However, participants that lacked a positive relationship with the pcp were not as receptive to the transition. Similar experiences were reported by those who had a nonexistent relationship with their pcp.

I became rather uncomfortable with my family physician.... I sort of lost faith [in him], but then he retired anyway and I moved on to a new doctor. But, like I say, [my pcp is] not that familiar with me.

— PS 2

The lack of trust in the capacity of the pcp to properly provide follow-up cancer care resulted in anxiety for participating survivors: “How involved do they become in cancer care?” (PS 2)

Relationship with the TCC

Participants reported that the nurse practitioner in the tcc provided reassurance during the transition process. The nurse practitioner serving as a point of contact with the cancer care team also resulted in survivors being more comfortable with being cared for in a primary care setting. The preparedness and thoroughness of the tcc appointment, as well as trust in the nurse practitioner’s capabilities, contributed to participant confidence in the transition.

[The nurse practitioner] just gave me a lot more confidence, because that was her role and it wasn’t like I showed up for one test or appointment and suddenly was told, “Well, this appointment is to transition you out.”

— PS 9

Relationship with the Oncologist and Cancer Centre Team

Some participants reported that they were content with the care provided by their oncologist and cancer centre team and “would prefer it ... the way it was” (PS 2). However, other participants felt that they understood the reasons for transitioning from tertiary care and were more accepting towards the transition: “I know the cancer is gone.... This doesn’t require me going to the oncology department” (PS 8).

I understand why they were keeping me at Sunny-brook, but now there is no reason for me to go there anymore.... It’s time to move along. I don’t need to be seen by anybody of that credential anymore. I just need a routine follow-up with a doctor like a [pcp].

— PS 8

Furthermore, participants indicated that maintaining relationships with their cancer care team and “not [worrying] because you’re not being abandoned” (PS 9) were important.

I could of course always contact [my oncologist] even though I wasn’t coming annually anymore.

— PS 9

DISCUSSION

Since the landmark 2005 report from the Institute of Medicine, qualitative research conducted with survivors cared for by their pcps continues to inform patient-centric survivorship care24,26,27,29. Yet despite that growth in the literature, our study is, to the best of our knowledge, one of the first to focus on patient experiences during the transition to primary care.

Debono33 suggested that oncologists can facilitate the transition by being transparent and compassionate when introducing it and by using scps. Our findings support that approach, with participants being more receptive to the transition if it is introduced in a way that allows them to “brace” for it. A well-established relationship with oncologists and the cancer centre team can also be conducive to transition readiness, especially if the reasons for the transition are disclosed to the survivor. Although scps were appreciated by our participants, the scps were insufficient for easing the transition—a concern previously reported by breast cancer survivors26. A conspicuous and concise “roadmap” for survivorship care used in conjunction with scps might prove useful.

The survivor experiences revealed through our study build on Debono’s recommendations. Support from all health care providers, presenting a concerted effort to provide reassurance that the “quality of care will be the same,” can ease the process. Moreover, participant relationships with the pcp were seemingly the most polarizing facilitator or barrier during transition. The participants with well-established and positive relationships with their pcps reported better experiences. In contrast, those lacking such a relationship understandably questioned “how involved [pcps] become in cancer care.” The survivor relationship with the pcp therefore warrants consideration during the assessment of transition readiness.

The readiness of patients to be discharged from health care institutions is an important consideration in patient-centred transitions in care, but the assessment of readiness is often a provider-and system-centric process34. Research about the concept of readiness for discharge have included diverse patient populations (such as post-anesthesia, surgical, elderly, and mothers and their newborns); however, none have focused on cancer survivors. The Readiness for Hospital Discharge Scale (rhds) was developed to assess readiness for discharge from the patient’s perspective and consists of 21 “readiness items”35. The concern for the clarity of the timeline identified by participants in the present study echoed the “knowledge of follow-up plan” item in the rhds. Participant discussions about how other factors affected their readiness to transition from tertiary to primary care shed light on how the rhds concept might be applied for cancer survivors.

The transition readiness of adult cancer survivors was also explored through the context of self-management36, which forms part of the conceptual basis for the rhds35. Kvale and colleagues36 made use of a framework based on Bandura’s health belief model37 and on social cognitive theory38 to understand factors affecting uptake of self-management in breast cancer survivors after active treatment. In contrast to the present study, their conceptual framework was developed a priori and directed their analysis. Several conceptual frameworks also exist for the transition readiness of childhood cancer survivors to adult-oriented follow-up care39. Those frameworks include smart (the Social-ecological Model of Adolescents and Young Adults Readiness to Transition)40 and the transtheoretical model41. Despite the use of those models, more research is needed to understand both foregoing types of transitions. That ongoing need could be a testament to the complexity of transition readiness, highlighting the need for research to understand its impact on the burgeoning population of adult cancer survivors transitioning to pcp-exclusive survivorship care.

As health care systems and practices adapt to meet the demand for specialized oncology services, transition readiness as understood from the survivor’s perspective can play a pivotal role in ensuring patient-centred care. However, system-related issues surrounding that transition must also be addressed. A study of pcps and oncologists found significant differences in their knowledge, attitudes, and practices when caring for cancer survivors42. More effective communication42 and capacity-building initiatives are needed to overcome those systemic barriers to pcp-exclusive survivorship care8. Models such as the tcc that tap into the ability of pcps to provide survivorship care warrant more rigorous evaluation from the perspectives of health care providers and of systems. A health care system conducive to a cancer survivor’s transition to a pcp can provide high-quality patient-centric care that will provide the survivor with confidence that they will not “[fall] through the cracks.”

Although insightful, our study should be understood in light of its limitations. First, the use of a qualitative methodology has inherent threats to generalizability43. Participants were either gastrointestinal cancer or lymphoma survivors who were treated in the Odette Cancer Centre, potentially limiting the applicability of our results for other survivors. A more diverse sample of cancer survivors might provide a broader perspective. Also, the sample consisted of individuals who had already been referred to the tcc, and survivors might or might not have different experiences with other models of survivorship care. Furthermore, it should be noted that our study took place in Canada, where all medically necessary care is guaranteed without regard to the setting (primary or tertiary). Experiences of cancer survivors in other health care systems, such as private health systems, might be affected by the prevailing payment structure44. Although not necessarily a limitation, our switch from the original method of data collection (focus groups) to telephone interviews for non-methodologic reasons, including accrual and convenience for the participants, is worth noting.

CONCLUSIONS

Our study provides insights into the experiences of survivors during their transition to primary care. Survivor transition readiness is affected by many factors, with their relationships with pcps being particularly impactful. Understanding transition readiness from the survivor perspective could prove useful in ensuring patient-centred care. As health care systems adapt to meet the demand for specialist care, it is increasingly important to ensure that survivors, as well as health care providers and institutions, are ready for the transition from tertiary to primary care.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank everyone who took the time to participate in this study. We also thank Ruby Sangha (nurse practitioner) for her valuable insights and assistance during the recruitment process. This study was supported by the Academic Health Science Centre Alternative Funding Plan Innovation Fund and the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. Preliminary findings from the study were presented in an abstract during oicr/cco Health Services Research Program 7th Annual Meeting.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES

We have read and understood Current Oncology’s policy on disclosing conflicts of interest, and we declare that we have none.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hewitt M, Greenfield S, Stovall E, editors. From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Halpern MT, Viswanathan M, Evans TS, Birken SA, Basch E, Mayer DK. Models of cancer survivorship care: overview and summary of current evidence. J Oncol Pract. 2015;11:e19–27. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2014.001403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McCabe MS, Jacobs L. Survivorship care: models and programs. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2008;24:202–7. doi: 10.1016/j.soncn.2008.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McCabe MS, Jacobs LA. Clinical update: survivorship care—models and programs. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2012;28:e1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.soncn.2012.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCabe MS, Bhatia S, Oeffinger KC, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology statement: achieving high-quality cancer survivorship care. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:631–40. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.46.6854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kirsch B. Many US cancer survivors still lost in transition. Lancet. 2012;379:1865–6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60794-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Canadian Cancer Society’s Advisory Committee on Cancer Statistics. Canadian Cancer Statistics 2015. Toronto, ON: Canadian Cancer Society; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Del Giudice ME, Grunfeld E, Harvey BJ, Piliotis E, Verma S. Primary care physicians’ views of routine follow-up care of cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3338–45. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.4883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Erikson C, Salsberg E, Forte G, Bruinooge S, Goldstein M. Future supply and demand for oncologists: challenges to assuring access to oncology services. J Oncol Pract. 2007;3:79–86. doi: 10.1200/JOP.0723601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grunfeld E, Whelan TJ, Zitzelsberger L, Willan AR, Montesanto B, Evans WK. Cancer care workers in Ontario: prevalence of burnout, job stress and job satisfaction. CMAJ. 2000;163:166–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grunfeld E, Gray A, Mant D, et al. Follow-up of breast cancer in primary care vs specialist care: results of an economic evaluation. Br J Cancer. 1999;79:1227–33. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grunfeld E, Levine MN, Julian JA, et al. Randomized trial of long-term follow-up for early-stage breast cancer: a comparison of family physician versus specialist care. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:848–55. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.2235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wattchow DA, Weller DP, Esterman A, et al. General practice vs surgical-based follow-up for patients with colon cancer: randomised controlled trial. Br J Cancer. 2006;94:1116–21. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mahboubi A, Lejeune C, Coriat R, et al. Which patients with colorectal cancer are followed up by general practitioners? A population-based study. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2007;16:535–41. doi: 10.1097/CEJ.0b013e32801023a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baena-Canada JM, Ramirez-Daffos P, Cortes-Carmona C, Rosado-Varela P, Nieto-Vera J, Benitez-Rodriguez E. Follow-up of long-term survivors of breast cancer in primary care versus specialist attention. Fam Pract. 2013;30:525–32. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmt030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grunfeld E, Fitzpatrick R, Mant D, et al. Comparison of breast cancer patient satisfaction with follow-up in primary care versus specialist care: results from a randomized controlled trial. Br J Gen Pract. 1999;49:705–10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pollack LA, Adamache W, Ryerson AB, Eheman CR, Richardson LC. Care of long-term cancer survivors: physicians seen by Medicare enrollees surviving longer than 5 years. Cancer. 2009;115:5284–95. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Siegel R, DeSantis C, Virgo K, et al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62:220–41. doi: 10.3322/caac.21149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ogle KS, Swanson GM, Woods N, Azzouz F. Cancer and comorbidity: redefining chronic diseases. Cancer. 2000;88:653–63. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(20000201)88:3<653::AID-CNCR24>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.El-Shami K, Oeffinger KC, Erb NL, et al. American Cancer Society colorectal cancer survivorship care guidelines. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:427–55. doi: 10.3322/caac.21286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thompson CA, Mauck K, Havyer R, Bhagra A, Kalsi H, Hayes SN. Care of the adult Hodgkin lymphoma survivor. Am J Med. 2011;124:1106–12. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2011.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.United States, The National Academies, Institute of Medicine, Committee on Quality of Health Care in America . Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grunfeld E, Earle CC. The interface between primary and oncology specialty care: treatment through survivorship. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2010;2010:25–30. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgq002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hudson SV, Miller SM, Hemler J, et al. Adult cancer survivors discuss follow-up in primary care: “Not what I want, but maybe what I need”. Ann Fam Med. 2012;10:418–27. doi: 10.1370/afm.1379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brennan M, Butow P, Spillane AJ, Marven M, Boyle FM. Follow up after breast cancer—views of Australian women. Aust Fam Physician. 2011;40:311–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kantsiper M, McDonald EL, Geller G, Shockney L, Snyder C, Wolff AC. Transitioning to breast cancer survivorship: perspectives of patients, cancer specialists, and primary care providers. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(suppl 2):S459–66. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1000-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Khan NF, Evans J, Rose PW. A qualitative study of unmet needs and interactions with primary care among cancer survivors. Br J Cancer. 2011;105(suppl 1):S46–51. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sisler JJ, Taylor-Brown J, Nugent Z, et al. Continuity of care of colorectal cancer survivors at the end of treatment: the oncology–primary care interface. J Cancer Surviv. 2012;6:468–75. doi: 10.1007/s11764-012-0235-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Parry C, Morningstar E, Kendall J, Coleman EA. Working without a net: leukemia and lymphoma survivors’ perspectives on care delivery at end-of-treatment and beyond. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2011;29:175–98. doi: 10.1080/07347332.2010.548444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sandelowski M. What’s in a name? Qualitative description revisited. Res Nurs Health. 2010;33:77–84. doi: 10.1002/nur.20362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Neergaard MA, Olesen F, Andersen RS, Sondergaard J. Qualitative description—the poor cousin of health research? BMC Med Res Methodol. 2009;9:52. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-9-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pope C, Ziebland S, Mays N. Qualitative research in health care. Analysing qualitative data. BMJ. 2000;320:114–16. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7227.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Debono D. Coping with the oncology workforce shortage: transitioning oncology follow-up care to primary care providers. J Oncol Pract. 2010;6:203–5. doi: 10.1200/JOP.777005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Anthony MK, Hudson-Barr D. A patient-centered model of care for hospital discharge. Clin Nurs Res. 2004;13:117–36. doi: 10.1177/1054773804263165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weiss ME, Piacentine LB. Psychometric properties of the Readiness for Hospital Discharge Scale. J Nurs Meas. 2006;14:163–80. doi: 10.1891/jnm-v14i3a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kvale EA, Meneses K, Demark-Wahnefried W, Bakitas M, Ritchie C. Formative research in the development of a care transition intervention in breast cancer survivors. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2015;19:329–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2015.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bandura A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev. 1977;84:191–215. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bandura A. Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Educ Behav. 2004;31:143–64. doi: 10.1177/1090198104263660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Klassen AF, Rosenberg-Yunger ZR, D’Agostino NM, et al. The development of scales to measure childhood cancer survivors’ readiness for transition to long-term follow-up care as adults. Health Expect. 2015;18:1941–55. doi: 10.1111/hex.12241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schwartz LA, Brumley LD, Tuchman LK, et al. Stakeholder validation of a model of readiness for transition to adult care. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167:939–46. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.2223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sawicki GS, Lukens-Bull K, Yin X, et al. Measuring the transition readiness of youth with special healthcare needs: validation of the traq–Transition Readiness Assessment Questionnaire. J Pediatr Psychol. 2011;36:160–71. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsp128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Potosky AL, Han PK, Rowland J, et al. Differences between primary care physicians’ and oncologists’ knowledge, attitudes and practices regarding the care of cancer survivors. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26:1403–10. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1808-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Myers M. Qualitative research and the generalizability question: standing firm with Proteus. Qual Rep. 2000;4:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bohm K, Schmid A, Gotze R, Landwehr C, Rothgang H. Five types of oecd healthcare systems: empirical results of a deductive classification. Health Policy. 2013;113:258–69. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2013.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]