Short abstract

Engineer who invented computed tomography and won the Nobel prize for medicine

Sir Godfrey Hounsfield invented the computed tomographic scanner, and thus made an incomparable contribution to medicine. An engineer, he conceived the idea of computed tomography during a weekend ramble in 1967. Initially it had nothing to do with medicine but was simply “a realisation that you could determine what was in a box by taking readings at all angles through it.”

Back in his workshop at EMI research laboratories in Hayes, Middlesex, he began work on a computerised device that could process hundreds of x ray beams to obtain a two-dimensional display of the soft tissues inside a living organism. By recording on sensors rather than x ray film and taking multiple pictures from a rotating photon source, a series of “slices” could be photographed that showed the different density of tissues. By making a series of such photographs at close intervals, it was then possible to have a three-dimensional image. The mathematics behind this was phenomenal, and other more powerful and better resourced research teams had, unknown to Hounsfield, considered the idea and dismissed it as unworkable.

Soon he was practising on the head of a cow that a colleague obtained from a kosher slaughterhouse in east London, and he submitted his own brain for the first live human scan. The first patient was scanned in September 1971 at Atkinson Morley's Hospital in Wimbledon with the radiologist James Ambrose. The patient had a suspected brain cyst of uncertain location. Dr Ambrose recalled that the scan gave a clear indication of its whereabouts, and that he and Hounsfield felt like footballers who had just scored the winning goal.

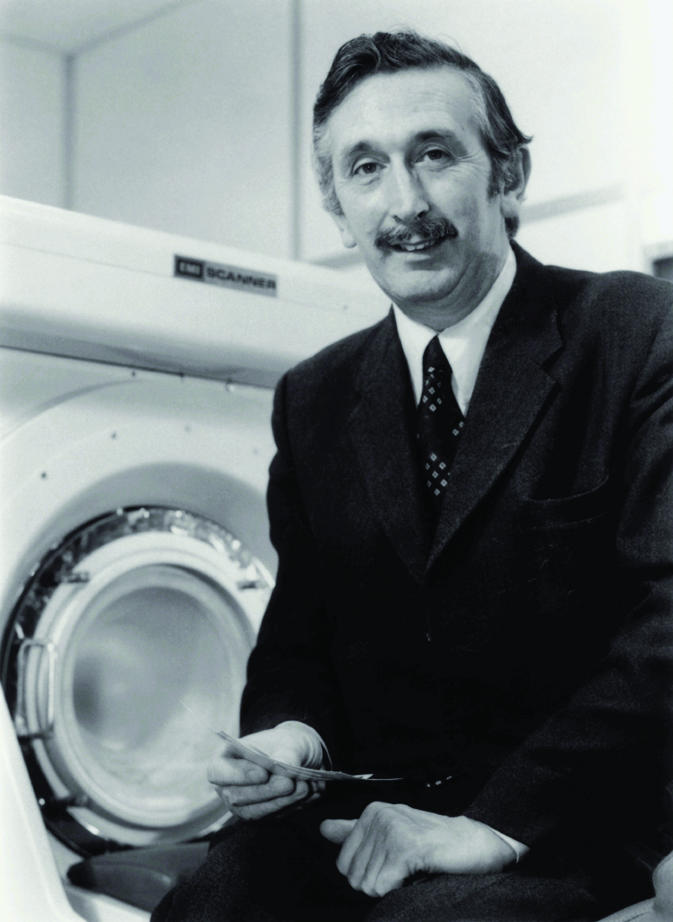

Figure 1.

Credit: SPL

Within a few months Hounsfield had developed a machine that could produce detailed cross-sections of the brain in four and a half minutes. The Department of Health and Social Security evaluated the machine and was so impressed that it underwrote EMI's production of the first five machines.

In October 1972 a machine was displayed to an audience of 2000 at the Chicago meeting of the Radiological Society of North America, and Dr Ambrose's accompanying lecture received a standing ovation. By 1973 the first computed tomographic scanners were being used clinically, first for the brain and then, after modification, for whole body imaging.

Hounsfield, a non-graduate, received the prestigious MacRobert award from the Council of Engineering Institutions in 1972, a Lasker award and fellowship of the Royal Society in 1975, a CBE in 1976, a Nobel prize in 1979, and a knighthood in 1981. He shared the Nobel prize with the South African nuclear physicist Allan Cormack, who had worked on similar lines and had published a paper in 1957 suggesting a reconstruction technique called the radon transform.

Hounsfield was the youngest of five children of a Nottinghamshire farmer, later describing the farm as a marvellous playground. He constructed electrical recording machines and nearly blew himself up using water-filled tar barrels and acetylene to see how high they could be propelled by water jet. At grammar school in Newark he excelled only in mathematics and physics. At the outbreak of the second world war he joined the Royal Air Force as a radar instructor, moving via the Royal College of Science to Cranwell Radar School. Air vice-marshall Cassidy was so impressed that after the war he got Hounsfield a grant to study for a diploma at Faraday House Engineering College.

In 1951 Hounsfield joined EMI to work on radar and guided weapons. From there he progressed to designing the magnetic drums and tape decks of early computers. He had no interest in power, position, or possessions. He was a modest man who lived modestly, enjoying country walks and his work. He worked long hours, and his colleagues stayed late because they enjoyed working with him. He had a sense of fun and he loved music. His colleagues found him enthusiastic, gentle, delightful, inspiring, “the nicest and most genuinely good person you could hope to meet.” On receiving his Nobel prize his advice to the young was, “Don't worry if you can't pass exams, so long as you feel you have understood the subject.” After his formal retirement he did voluntary work at the Royal Brompton and Heart hospitals.

His name is used to describe the brightness of tomograms, which are measured in Hounsfield units. He left his money to fund engineering research and scholarships. He died from a chronic and progressive lung disease, spending his last years in a nursing home. He was unmarried and unattached, and had no children.

Geoffrey Newbold Hounsfield, engineer (b 1919, CBE, FRS), d 12 August 2004.