Abstract

Objective

Caregiving partners constitute a unique group, who provide both physical and emotional care for patients. There has been extensive research conducted on caregivers during either the caregiving or bereavement phase; however, these phases are often treated as separate entities rather than as part of a continuum.

Method

In this paper, utilizing relevant literature and clinical observations, we map the emotional journey and lived experience of caregivers moving from disease progression, to the end of life, to the dying process itself, and then through life after the death of a partner. Along this journey, we identify the links between pre-death caregiving and bereavement.

Results

Our illustration raises awareness regarding the unmet needs experienced by caregiving partners across the continuum and provides an alternative framework through which clinicians can view this course.

Significance

of Results We bolster arguments for improved palliative care services and early interventions with distressed caregiving partners by emphasizing continuity of care both before and after a patient’s death.

Keywords: Caregiving, Bereavement, Continuity of care, Partners

INTRODUCTION

A cancer diagnosis is a life-altering event that extends beyond the patient, impacting the entire family. Upon diagnosis, the family routine is replaced by a whirlwind of hospital visits and medical treatments. During this time, the patient’s intimate partner often takes on the role of caretaker, handling the patient’s practical and physical needs while also providing emotional support. Partner and spousal caregivers constitute an extraordinary group, characterized by an intimate relationship with the patient at many levels and by special commitments and responsibilities associated with the caregiving role (Croog et al., 2006). As the recent trend toward longer survival involves more ambulatory and home care, the burden on caregiving partners will presumably be enlarged (Braun et al., 2007).

THE ROLE OF CAREGIVER

Due to the fears surrounding the uncertainty of a cancer diagnosis, partners often find themselves silently struggling with the balance of providing care to their loved one, while internally coping with the emotional distress of their partner’s illness (Masterson et al., 2013). The demands of this balancing act leave spouses vulnerable to carrying the highest rates of caregiver depression among all family care providers (Ling et al., 2013). Furthermore, elevated rates of depression and distress have been reported by caregiving partners that match or surpass that of the cancer patients themselves (Braun et al., 2007; Matthews, 2003).

The illness experience can be a long and arduous road, often described as an “emotional rollercoaster.” Caregiving partners are unexpectedly catapulted onto this ride and forced to navigate through new territory without a well-drawn map. If we are to combat psychological morbidity and foster healing, it is imperative to develop a comprehensive understanding of this experience.

THE NECESSITY OF CONTINUOUS CARE

There has been considerable attention directed at the experience of caregivers, both during caregiving and later on in bereavement. However, these two stages are often viewed as discrete and independent entities rather than as reciprocal experiences, in which anticipation of loss hangs over caregiving activities, and the time spent providing care gives shape to mourning (Li, 2005). Caregiving and bereavement are better treated as parts of a continuum rather than as isolated timepoints. Unfortunately, clinical bereavement care is commonly conceptualized as a discrete service, beginning only after the patient’s death. However, due to the high rates of psychological morbidity and depression for partner-caregivers during palliative care (Matthews, 2003; Braun et al., 2007), it is arguably most supportive when clinical attention is directed to caregivers prior to the patient’s death.

Few studies have utilized this continuous framework to examine bereavement as an outcome of the caregiving experience (Bednard-Dubenske et al., 2008). Those that have, however, found evidence to support the notion that caregiving involvement does in turn influence bereavement outcomes (Li, 2005; Schulz et al., 2003; Collins et al., 1993; Duke, 2002). Previous research has identified a number of factors that contribute to caregiver distress and depression, including high caregiver burden, negative cognitive appraisals, low social support, and low self-efficacy (Lee et al., 2013). During major events (i.e., recurrence, disease progression, death, etc.), complex relationships emerge between these risk factors as well as additional biological, financial, and social factors.

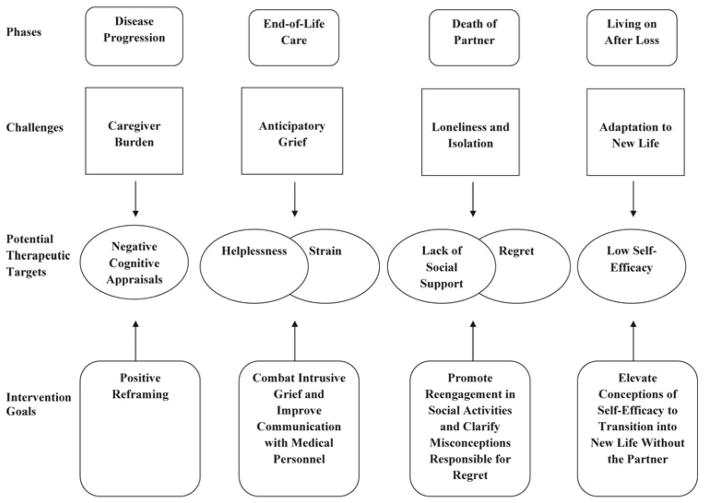

We depict here the lived experience of the partner-caregivers of cancer patients from diagnosis, through end-of-life experiences, and across the new chapter of life as a widow or widower. Derived from existing literature and clinical observations, we present an integrative model identifying four phases of the partner-caregiving experience: (1) disease progression, (2) end of life, (3) death of a partner, and (4) living on after loss. We highlight the reciprocity between the caregiving and bereavement experiences, and the challenges that characterize each phase, by synthesizing data from prior quantitative and qualitative studies of partner-caregivers. Finally, we underscore the need for continuous psychosocial care for caregivers prior to the patient’s death and through bereavement, while providing a model for clinicians to reference in order to foster healing throughout the illness experience.

PHASE ONE: DISEASE PROGRESSION (SEE FIGURE 1)

Fig. 1.

A model of continuous care for caregiving partners.

Challenge: Caregiver Burden

In response to the patient’s regressing physical state, caregiving tasks become more time consuming as well as physically demanding, leading to increased caregiver burden (Duke, 2002). At this time, the demands of caregivers are characterized by obligations, expectations, and restrictions (Duke, 2002): “Caregiver burden is considered a multidimensional biopsychosocial reaction resulting from an imbalance of care demands relative to the caregivers’ personal time, social roles, physical and emotional states, financial resources, and formal care resources, given the other multiple roles they fulfill” (Given et al., 2004, p. 1106).

While the cancer diagnosis was likely a devastating and shocking experience, this later period can place an unprecedented physical and mental burden on the caregiver. The increasing number of responsibilities leaves little time for outside activities; without this balance, partners are vulnerable to experiencing high distress and feelings of being overwhelmed. In order to provide needed care, many reallocate time previously spent on outside activities (e.g., employment, exercise, and social events) to the duties of caregiving (Navaie-Waliser et al., 2002). Although this decision is often made with the intention of reducing the strain associated with balancing multiple roles, the loss of time spent in outside domains can lead to exacerbated distress due to the financial consequences, poor health outcomes, and social isolation (Navaie-Waliser et al., 2002).

Potential Therapeutic Target: Negative Cognitive Appraisals

Negative cognitive appraisals have been found to contribute to caregiver distress during disease progression (Haley et al., 2003). Caregivers who perceive their role as threatening to overwhelm their personal coping resources experience higher psychological morbidity in response to the stress than those who perceive the stressor as holding potential for mastery or benefit (Folkman et al., 1986). Haley and colleagues (2003) conducted a study of 80 spousal caregivers in a hospice setting to examine the role of cognitive appraisal on caregiver depression and life satisfaction. Spouses’ subjective appraisals regarding both the stressfulness and perceived benefits of caregiving tasks were more strongly associated with caregiver depression and life satisfaction than were any objective indicators of stress (i.e., level of patient impairment, duration of caregiving period, etc.) or demographics (Haley et al., 2003).

Phase One Intervention Goal: Positive Reframing

The appraisal that the caregiving experience holds potential for mastery and benefit creates an opportunity for caregivers to engage in meaning-making and benefit-finding during this stressful time. When the appraisal is positive, providing care enables caregivers to engage in a productive activity that relieves their distress while improving the patient’s quality of life (Braun et al., 2007). In turn, caregiving partners are able to identify the importance of their role as caregiver and find meaning in it: “I learned a lot about myself and found it a growing experience” (Collins et al., 1993, p. 246).

Pride in one’s ability to provide care can be a powerful antidote to distress, and can generate resilience for the road ahead. However, processes such as finding benefit and meaning, using coping strategies, and seeking support require a measure of focus on the self, which may be confusing to caregivers who subsume their own needs to the caregiver role. Indeed, seemingly contradictory feelings regarding a need to focus on oneself versus a need to focus on the patient often result in intense distress for caregiving partners (Pusa et al., 2012). Feelings of loyalty to the patient often prevent caregiving partners from seeking support despite their high levels of distress and strong need for disclosure (Pusa et al., 2012). Clinicians can assess the extent to which a partner’s perception of caregiving can accommodate self-care. In addition, in order to facilitate caregiver attendance, clinicians must demonstrate awareness and sensitivity to the overwhelming schedules of caregivers by providing flexible and. if necessary, transportable care.

PHASE TWO: END OF LIFE (SEE FIGURE 1)

Challenge: Anticipatory Grief

The transition to end-of-life care can be challenging for caregivers, as the realization of impending loss must be integrated into caretaking activities in the present. Anticipatory grief has been defined as a phenomenon that encompasses the process of mourning, coping, interaction, planning, and psychosocial reorganization that are stimulated in response to the impending loss of a loved one, as well as associated losses in the past, present, and future (Holley & Mast, 2009). Unfortunately, the end of life is often characterized by changes in a patient’s personality, appearance, and spirit. As patients lose the beloved traits and characteristics that once denned them, partners can often experience grief for the loss of the person they loved long before the patient’s physical death. In a study of 82 primary family caregivers, 54% reported such loss of familiarity in the relationship with the patient preceding his/her death (Collins et al., 1993):

My wife died so many times before her actual death. It took so much out of me. I went through each day wondering when it would all end.

(Collins et al., 1993, p. 244)

Intense or pathological anticipatory grief has been reported in a substantial number of caregivers (15–30%) during palliative care (Kim & Carver, 2012). Intense anticipatory grief has been correlated with caregiver burden and can be a predictor of later depression (Holley & Mast, 2009). However, not all expressions of anticipatory grief are pathological. During normative anticipatory grief, family members are able to work through emotional distress associated with grief, resolve any enduring conflicts, and reduce attachment to lessen the emotional impact of the patient’s impending death (Collins et al., 1993).

Potential Therapeutic Target: Strain

At the end of life, caregiving presents new challenges. Caregivers grieve the pending loss of their spouse, lose hope for the patient’s recovery, and reach their limits in terms of providing care. Intense and enduring strain during this phase calls for the help of other informal and formal caregivers to manage the demands of caregiving. Female patients are more likely to receive care from adult children and other relatives in addition to their male partners, while male patients receive help mainly from their partners (Allen, 1994). It is possible that, compared to male caregivers, female caregivers wait until they have reached their personal limits to seek help, explaining the findings of female caregivers reporting a greater degree of unmet needs than male carers (Navaie-Waliser et al., 2002):

I felt like my life had come to a stop. I was concentrating on many things. I just couldn’t think anymore. I knew my husband was going to die, but I didn’t know how or when, and I didn’t know if I wanted to know these things. Everything was so uncertain, and I felt in complete limbo.

(Duke, 2002, p. 833)

When discussing their grief, 32% of spousal caregivers referred to the emotional and physical impacts of the final stages of caregiving:

I was stretched physically, emotionally, and spiritually. Caregiving drained me, and I was exhausted.

(Collins et al., 1993, p. 244)

At the end of life, as intense emotions as well as physical and mental exhaustion set in, partners are often called upon to fulfill the role of patient advocate and proxy informant. During palliative care, partners are frequently needed to make important medical decisions on behalf of the incapacitated patient; too often, these decisions are a matter of life and death. Many caregivers report feeling ignored by medical personnel and naïve to the medical services that their partner was receiving:

You did not know what was going to happen the next day, what examination he would have or anything.

(Pusa et al., 2012, p. 37)

Caregivers who are forced to make uninformed decisions are vulnerable to experiencing regret following the death of the patient, a key risk factor for poor bereavement outcomes. It is imperative that medical personnel provide comprehensive and accurate medical information to caregivers in order to avoid unnecessary feelings of regret during bereavement (Pusa et al., 2012).

Potential Therapeutic Target: Helplessness

The approach of death may also bring on feelings of helplessness. Caregivers may feel increasingly powerless as their loved one experiences symptoms that they cannot relieve—such as pain, nausea, breathlessness, or the inability to eat (Beng et al., 2013; Milberg et al., 2004; Yamagishi et al., 2010). A dawning awareness that their loved one is inevitably slipping away can produce a profound feeling of helplessness in the face of this ultimate loss of control:

After the operation. I was told that it was incurable [the doctor’s words] … I, who all my life—I am 75—have been used to organizing and deciding everything together with my family about our lives, I was suddenly totally helpless. I was seized with deep powerlessness when I understood that I couldn’t do anything to help my wife.

(Milberg et al., 2004, p. 124)

Phase Two Intervention Goals: Combat Intrusive Grief and Improve Communication with Medical Personnel

It is imperative for skilled clinicians to differentiate between normative and pathological anticipatory grief during this phase. Intrusive symptoms of anticipatory grief such as sadness and feelings of isolation need to be recognized by clinicians and addressed in order to protect against psychological morbidity in bereavement. Similarly, clinicians can support caregivers by helping them to distinguish between domains in which they do and do not have instrumental control, and in finding ways to cope (e.g., acceptance) with what cannot be changed. The prevalence of grief prior to the patient’s death alone bolsters arguments for introduction of clinical services for caregivers during the palliative care stage. Without continuity of care, caregivers exhibiting maladaptive forms of anticipatory grief will likely spiral downward into deep realms of depression, forcing the clinicians providing discrete bereavement services to take a reactive rather than a proactive approach to care.

PHASE THREE: DEATH OF A PARTNER (SEE FIGURE 1)

While the caregiving period can be taxing, the death of a partner is a final and extremely personal event for anyone. Rates of distress and depression, use of medication, number of days sick, and even mortality rates are reported to be higher for widowed individuals as opposed to still-married counterparts (Stroebe et al., 2001). Despite a prolonged duration of caregiving and warnings of a poor prognosis, many partners report a sense of shock and unreality upon the death of the patient, and the beginning of a profoundly different experience than any other leading up to the death:

Nothing that happened before the death of my wife was anything like the time since—nothing. Nothing could have prepared me for the impact that her death had on me. The time after her death was completely and dreadfully different.

(Duke, 2002, p. 836)

Challenge: Loneliness and Isolation

The death of such a beloved partner can be exceptionally difficult for the bereaved and can cause deep feelings of loneliness and isolation. In some instances, bereaved caregivers report feelings of such intense loneliness that they feel isolated even from themselves:

I was terribly empty. My body was there, but there was nothing inside.

(Duke, 2002, p. 834)

Loneliness in response to the death of a partner is a common and well-known outcome. During this time, it is typical for the bereaved caregiver’s social support network to mobilize in an attempt to offset these feelings. Although the emotions of grief are difficult to endure, continued social support has been shown to help the bereaved by providing a venue for emotional expression as well as practical help with housework and meal preparation (Duke, 2002).

Potential Therapeutic Target: Lack of Social Support

While the mobilization of social support is helpful, it signals the beginning of a distinct role reversal for the bereaved. While the patient was alive, most partners spent the majority of their time providing care to the patient, and had likely formulated an identity surrounding their role as a caregiver. However, upon the death of the patient, the caregiver becomes the one in need of support (Duke, 2002). This role reversal requires adjustment, yet it is often comforting to know that caregivers can rely on help from others to work through this difficult transition.

Identification of partners at risk for complicated bereavement permits an opportunity for determining when preventative and treatment interventions are warranted and when an individual’s existing coping skills should be trusted to allow for natural resilience (Lichtenthal & Sweeney, in progress). Bonanno and colleagues (2004) identified five types of bereaved spouses and their respective patterns of resilience or maladjustment in the time following the patient’s death. The five trajectories were termed: (1) resilient; (2) depressed-improved, likely meaning “initially sad prior to improving”; (3) common grief; (4) chronic grief; and (5) chronic depression. In their study, spouses with low distress comprised more than half of the sample. The majority of spouses (45.9%) belonged to the resilient group and experienced low distress throughout the study, while the remaining spouses (10.2%) experienced depressive symptoms prior to the loss but their functioning improved following the death of the patient (Bonanno et al., 2004).

Potential Therapeutic Target: Regret

While previous work identifying trajectories for bereaved spouses has found that most spouses demonstrate resiliency as they move through bereavement (Bonanno et al., 2004), the factors that may contribute to problematic bereavement outcomes are still a matter of great interest. Clinically, regret during bereavement is often discussed, but the relationship between regret and grief had not previously been examined empirically. Holland and coworkers (2013) utilized 201 bereaved participants to examine the trajectories of bereavement-related regret at 6, 18, and 48 months after loss. In accordance with previous bereavement work that has highlighted the resiliency of bereaved spouses, the most common trajectory was one of stable low-level regret (Holland et al., 2013). The second group demonstrated consistently high levels of regret, while the third group, “worsening high regret,” reported high levels regret at the six-month timepoint, which consistently worsened over time. The “worsening high regret” trajectory was the only trajectory associated with poorer grief outcomes (Holland et al., 2013). This finding demonstrates the profound effects that bereavement-related regret can have and continue to have during bereavement.

Following the death of the patient, feelings of suspense are replaced by vented feelings and efforts to maintain emotional balance despite a huge range of emotions and feelings (Duke, 2002). The cessation of uncertainty offers caregivers feelings of peace and relief. Partners express relief related to both the suffering for the patient and the cessation of caregiving responsibilities:

It was quite a relief not having that constant watch and not knowing what the next step will be to conquer. Not knowing what was in store made each new day hard to face. I’m glad it is over.

(Collins et al., 1993, p. 245)

Phase Three Intervention Goals: Promote Reengagement in Social Activities and Clarify Misconceptions Responsible for Regret

It is important for clinicians working in this sector to elicit caregiver perceptions of the experience of the loss of a loved family member prior to and following their death. When describing their grief, caregivers often reminisce about their experiences during the caregiving period (Collins et al., 1993). Unfortunately, a number of spouses express doubt and uncertainty about the decisions they had made regarding the patient’s care and regret for the way they had cared for their spouse while he/she was living (Collins et al., 1993). These feelings of regret can lead to social isolation, distress, and complicated bereavement. The continuous care model provides clinicians with an optimal vantage point from which to combat this regret. The presence of the clinician prior to the death of the patient affords them the opportunity to identify the gifts that the caregiver was able to provide the patient with leading up to the death. The presence of the clinician at the end of life gives this argument unprecedented credibility and improves the odds of the caretaker setting aside regret and acknowledging his/her contribution.

Partners who view their caregiving experience as important and meaningful are able to find comfort during bereavement from the care they had delivered (Collins et al., 1993; Duke, 2002). Rather than regret, they take pride in what they were able to do for their partners toward the end of their lives:

I’m glad I could care for my husband at home. I feel like I gave better care than he could have gotten anywhere else.

(Collins et al., 1993, p. 246)

I’d do it all over again. It was warm, loving, and a growing experience.

(Collins et al., 1993, p. 246)

PHASE FOUR: LIVING ON AFTER LOSS (SEE FIGURE 1)

Challenge: Adaptation to New Life

The death of a partner requires the bereaved spouse to reorganize nearly every aspect of his or her life from their daily routine to plans for the future (Bauer & Bonanno, 2001). In embarking on these major life alterations, the bereaved must take part in a narrative process of self-evaluation, reflecting on what they do, their values, and what they will become (Bauer & Bonanno, 2001). Their self-efficacy supports their desire to live a fulfilling future life and plays an important role in these evaluations and in one’s ability to choose new and adaptive courses of action (Folkman et al., 1986). In previous studies, some bereaved spouses have been shown to have lower levels of self-efficacy regarding their abilities than married individuals and more anxiety surrounding their recovery and future:

I can’t find any purpose in life after losing my wife. I am just thinking about what will happen to me and where I am going.

(Ishida et al., 2012, p. 509)

Despite its demonstrated influence on bereavement outcomes, research has not thoroughly examined the role of self-efficacy in adjustment to bereavement for widows and widowers. One study that examined this relationship (Bauer & Bonanno, 2001) discovered that participants who made positive evaluations about their abilities to carry on in the absence of their departed spouse had lower levels of grief over time compared to those who did not express self-efficacy.

Potential Therapeutic Target: Low-Self Efficacy

Following the initial period of grief, the bereaved spouse must begin to move forward and establish a new life and identity without their former partner. A study examining bereaved spouses’ adjustment after a patient’s death collected self-report data at 1, 3, and 13 months after the death (Carlsson & Nilsson, 2007). The loss of their partner required many bereaved spouses to take on roles and responsibilities in the household that they have never participated in before, like solving practical problems, taking care of finances, and traveling on their own (Carlsson & Nilsson, 2007). Although previous studies have cited these role changes as a source of stress, the participants in this sample appraised these to be positive experiences, holding potential for mastery and benefit.

Many significant others experience a transformation of their attitudes toward life, including reevaluations of what is most important (Pusa et al., 2012). An appreciation of life and health is often present after watching a loved one succumb to illness:

It feels like more— it sounds a bit clichéd to say that sometimes, but just when things like this happen, you are very happy to live. And I’m very glad that I am not sick, that I feel …

(Pusa et al., 2012, p. 38)

Carlsson and Nilsson (2007) uncovered some encouraging findings related to adjustment. At 3 months post-death, 69% of spouses had a positive or mostly positive outlook on the future. By 13 months, 83% viewed the future positively, and, further, 93% of spouses thought they had adjusted well or fairly well to life without their partner (Carlsson & Nilsson, 2007).

Phase Four Intervention Goals: Elevate Conceptions of Self-Efficacy to Transition into New Life Without the Partner

In the later phases of bereavement, adjusting to life without one’s partner presents as a primary challenge. Both self-efficacy and social support have been shown to be important factors during this time of transition. With low self-esteem, bereaved partners have little motivation, confidence, or skill to move out of the bereavement phase and turn the page to a new chapter of their lives (van Baarsen, 2002). Furthermore, low self-esteem may discourage widows and widowers from engaging socially and developing new relationships. Hindered by intense feelings of loneliness, partners with low self-efficacy will be unable to progress to the final phase of adjustment. A caregiver who continues to experience intense loneliness well into bereavement may have underlying insecurities regarding their ability to live a fulfilling life without their partner.

During this phase, it is important that clinicians are cognizant of the relationship between low self-efficacy and social support/social engagement. The model of continuous care provides clinicians with a great advantage in improving feelings of self-efficacy among bereaved caregivers. With knowledge of the often extraordinary abilities that these partners displayed during the previous phases (e.g., balancing multiple roles, acting as the patient’s advocate, providing emotional support), clinicians are able to foster feelings of pride in the bereaved partner’s abilities to excel even during periods of extreme stress. As bereaved partners formulate positive perceptions of themselves and attain higher self-efficacy, the engagement in social activities that is so necessary to positive adjustment during this phase will naturally follow.

CONCLUSION

Our model of continuous care identifies the challenges faced by caregiving partners of cancer patients and opportunities for intervention across the four phases of the illness trajectory: (1) disease progression, (2) end of life, (3) death of a partner, and (4) living on after loss. Furthermore, this illustration suggests that depressive symptomatology during the caregiving period can continue for months, if not years, into bereavement. Importantly, the majority recover satisfactorily. However, the extended nature of this emotional course provides numerous windows of opportunity for clinicians to take a proactive approach to providing continuity of care across these phases for those who have difficulties meeting the challenges.

Currently, discrete clinical services dominate the field, and early interventions during illness progression and palliative care are all too rare. As the patient’s treatment transitions from curative to palliative, patients and caregivers often report feelings of being abandoned and betrayed by the medical team. These feelings can resonate strongly for caregivers following the patient’s death. This model of continuous care encourages clinicians to support cancer caregivers across the illness trajectory, to build rapport through maintaining flexibility, and to remain sensitive as their needs shift across phases. We present an integrative model through which clinicians can gain an understanding of the landscape of the illness experience to illuminate the path to healing. By helping caregivers to avoid the pitfalls associated with later problems, they are afforded the opportunity to build resilience proactively, and early on rather than during the latter phases of the trajectory. While this model introduces a framework through which clinicians can view the illness experience, validation of the model and its ability to improve cancer caregiver outcomes over and above more fragmented approaches is warranted. Additionally, further research is warranted to identify if this model of continuous care proves to be an effective intervention for partners caring for patients with other chronic illnesses, such as dementia.

The model provides a framework for prospective research on dynamic, reciprocal relations between caregiving and grief, and to evaluate the relative merits of interventions based on the continuous-care model, over and above more typical fragmented service models, for outcomes such as distress, resolution of grief, regret, and satisfaction with care. Most importantly, in bridging the caregiving and post-bereavement experiences, the model reflects the challenges of having a terminally ill partner, as lived by the caregiver, allowing clinicians to empathically and skillfully support caregivers through multiple transitions, and to help them draw strength from their acts of care.

Acknowledgments

A special thank you to the clinical research staff of the Family Focused Grief Therapy study (funded by National Cancer Institute grant number 5R01CA115329-06), particularly Dr. Tammy Schuler and Shira Hichenberg, for their guidance and contributions. We would also like to thank the participants of the reviewed studies for sharing their experiences and providing us with information that will be essential in helping spousal caregivers of the future.

References

- Allen SM. Gender differences in spousal caregiving and unmet need for care. Journal of Gerontology. 1994;49(4):187–195. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.4.s187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer J, Bonanno GA. I can, I do, I am: The narrative differentiation of self-efficacy and other self-evaluations while adapting to bereavement. Journal of Research in Personality. 2001;35:424–448. [Google Scholar]

- Bednard-DuBenske LL, Wen K, Gustafson DH, et al. Caregivers’ differing needs across key experiences of the advanced cancer disease trajectory. Palliative & Supportive Care. 2008;6(3):265–272. doi: 10.1017/S1478951508000400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beng TS, Guan C, Seang LK, et al. The experiences of suffering of palliative care informal caregivers in Malaysia: A thematic analysis. The American Journal of Hospice & Palliative Care. 2013;30(5):473–489. doi: 10.1177/1049909112473633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno GA, Wortman CB, Nesse RM. Prospective patterns of resilience and maladjustment during widowhood. Psychology and Aging. 2004;19(2):260–271. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.19.2.260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun M, Mikulincer M, Rydall A, et al. Hidden morbidity in cancer: Spouse caregivers. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2007;25(30):4829–4834. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.0909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlsson ME, Nilsson IM. Bereaved spouses’ adjustment after the patients’ death in palliative care. Palliative & Supportive Care. 2007;5:397–404. doi: 10.1017/s1478951507000594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins C, Liken M, King S, et al. Loss and grief among family caregivers of relatives with dementia. Qualitative Health Research. 1993;3(2):236–253. [Google Scholar]

- Croog SH, Burleson JA, Sudilovsky A, et al. Spouse caregivers of Alzheimer patients: Problem responses to caregiver burden. Aging & Mental Health. 2006;10(2):87–100. doi: 10.1080/13607860500492498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duke S. An exploration of anticipatory grief: The lived experience of people during their spouses’ terminal illness and in bereavement. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2002;28(4):829–839. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1998.00742.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman S, Lazarus RS, Dunkel-Schetter C, et al. Dynamics of a stressful encounter: Cognitive appraisal, coping, and encountering outcomes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;50(5):992–1003. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.50.5.992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Given B, Wyatt G, Given C, et al. Burden and depression among caregivers of patients with cancer at the end of life. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2004;31(6):1105–1115. doi: 10.1188/04.ONF.1105-1117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haley WE, LaMonde LA, Han B, et al. Predictors of depression and life satisfaction among spousal caregivers in hospice: Application of a stress process model. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2003;6(2):215–224. doi: 10.1089/109662103764978461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland JM, Thompson C, Rozalski V, et al. Bereavement-related regret trajectories among older adults. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2013;69(1):41–47. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbt050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holley CK, Mast BT. The impact of anticipatory grief on caregiver burden in dementia caregivers. The Gerontologist. 2009;49(3):388–396. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnp061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishida M, Onishi H, Matsubara M, et al. Psychological distress of the bereaved seeking medical counseling at a cancer center. Japanese Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2012;42(6):506–512. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hys051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y, Carver CS. Recognizing the value and needs of the caregiver in oncology. Current Opinion in Supportive and Palliative Care. 2012;6(2):280–288. doi: 10.1097/SPC.0b013e3283526999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee KC, Chang W, Chou W, et al. Longitudinal changes and predictors of caregiving burden while providing end-of-life care for terminally ill cancer patients. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2013;16(6):632–637. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2012.0499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li LW. From caregiving to bereavement: Trajectories of depressive symptoms among wife and daughter caregivers. Journal of Gerontology. 2005;60B(4):P190–P198. doi: 10.1093/geronb/60.4.p190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenthal WG, Sweeney C. Families “at risk” of complicated bereavement (in progress) [Google Scholar]

- Ling S, Chen M, Li C, et al. Trajectory and influencing factors of depressive symptoms in family caregivers before and after the death of terminally ill patients with cancer. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2013;40(1):E32–E40. doi: 10.1188/13.ONF.E32-E40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masterson MP, Schuler TA, Kissane DW. Family focused grief therapy: A versatile intervention in palliative care and bereavement. Bereavement Care. 2013;32(3):117–123. doi: 10.1080/02682621.2013.854544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews A. Role of gender differences in cancer-related distress: A comparison of survivor and caregiver self-reports. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2003;30(3):493–499. doi: 10.1188/03.ONF.493-499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milberg A, Strang P, Jakobsson M. Next of kin’s experience of powerlessness and helplessness in palliative home care. Supportive Cancer in Care. 2004;12:120–128. doi: 10.1007/s00520-003-0569-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navaie-Waliser M, Spriggs A, Felman P. Informal caregiving: Differential experiences by gender. Medical Care. 2002;40(12):1249–1259. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000036408.76220.1F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pusa S, Persson C, Sundin K. Significant others’ lived experiences following a lung cancer trajectory: From diagnosis through and after the death of a family member. European Journal of Oncology Nursing. 2012;16:34–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2011.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz R, Mendelsohn AB, Haley WE, et al. End-of-life care and the effects of bereavement on family caregivers of persons with dementia. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2003;349:1936–1942. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa035373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroebe M, Stroebe W, Schut H. Gender differences in adjustment to bereavement: An empirical and theoretical review. Review of General Psychology. 2001;5(1):62–83. [Google Scholar]

- van Baarsen B. Theories on coping with loss: The impact of social support and self-esteem on adjustment to emotional and societal loneliness following a partner’s death in later life. Journal of Gerontology. 2002;57B(1):S33–S42. doi: 10.1093/geronb/57.1.s33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamagishi A, Morita T, Miyashita M, et al. The care strategy for families of terminally ill cancer patients who become unable to take nourishment orally: Recommendations from a nationwide survey of bereaved family members’ experiences. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2010;40(5):671–683. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]