Flavour capsules in cigarette filters are a product design innovation that allows consumers to crush a liquid-filled capsule that flavours the cigarette smoke. Most capsules include menthol flavourings, with chemosensory properties including a cooling, anaesthetic effect that makes it easier to inhale cigarette smoke, promotes misperceptions of harm and increases the appeal of smoking for youth.1–3 Industry pretesting revealed the attractiveness of choosing if and when to crush the capsule for the flavour, but cautioned that this novelty may wear off.4 Nevertheless, since the initial introduction of flavour capsule cigarettes in the Japanese market in 2007, capsule brand variants have been introduced worldwide. Industry reports and independent research indicate a number of countries where market share for flavour capsule cigarettes has grown exponentially.5–7

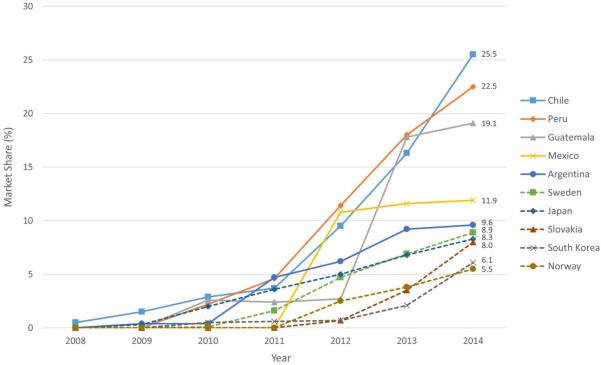

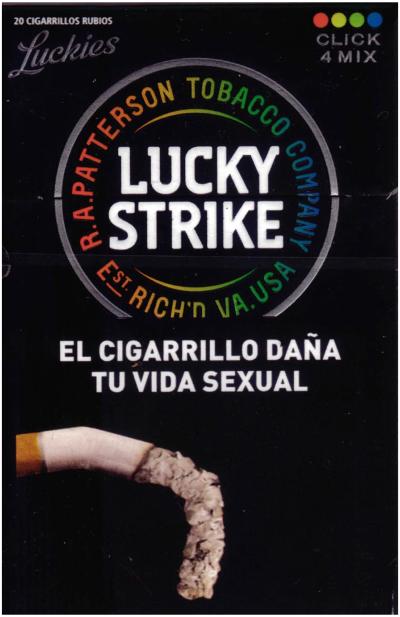

According to 2014 Euromonitor data,6 the top five countries with the highest market share for flavour capsule cigarettes are in the Latin American region: Chile, Peru, Guatemala, Mexico and Argentina (figure 1). For example, flavour capsule cigarette sales are estimated to account for more than a quarter of the cigarette market share in Chile, where flavour bans have been considered but effectively defeated by the industry. It is noteworthy that the growth of the flavour capsule market segment has often taken place in the context of relatively restrictive tobacco marketing bans that only permit marketing, including product displays, at point of sale (POS). Since 2013, Chile has banned all tobacco marketing, including at POS; however, flagrant violations are common and often involve flavour capsule cigarette varieties (figure 2). Industry marketing expenditures in the Latin American region are concentrated at POS,5,7,8 and civil society POS monitoring across the region has documented the prominence of flavour capsule cigarettes at the POS, including traditional product displays and novel package displays (eg, extremely large packaging).9 Although overall cigarette volume in the Latin American region has decreased, industry reports indicate that flavour capsule cigarettes have increased in total volume, despite price increases.5

Figure 1.

The 10 countries with largest market share for flavour capsules in 2014. Ten additional countries with market share ranging between 3% and 4% in 2014, are: Costa Rica, Finland, South Africa, Denmark, Czech Republic, Austria, Romania, UK, France and Slovenia.

Figure 2.

Flavour capsule pack display at point of sale in Chile, 2014.

Use and perceptions of flavour capsule cigarettes have been documented for adult smokers in Mexico.10 Between 2012 and 2014, preference for flavour capsules increased dramatically (0% to 14%), and those who preferred flavour capsule cigarettes were more likely to perceive benefits for their preferred brand compared to other brands, such as smoothness and lesser harm.10 Similar perceived benefits have been reported for flavour capsule users in Chile.11 In a 2015 survey in Mexico, early adolescents reported greater attractiveness of packaging, greater prior use and greater willingness to try flavour capsules compared to non-flavour capsule varieties.12 Additionally, the availability of flavour capsule brands in the discount segment of the market in the Latin American region may further enhance access and appeal among both youth and adults. This limited independent research, while troubling, highlights the need for more historical or prospective research on flavour capsule cigarette varieties.13

Over the past decade, other filter technology innovations have included flavoured polyethylene beads that slowly release flavours into the smoke but do not require that the smoker crush them; and filters that the smoker can twist to vary the concentrations of menthol in the smoke. It is critical to assess the appeal and potential public health impact of these technologies; nevertheless, our findings suggest that flavour capsules that consumers crush are of particular concern due to their growing market share globally. Tobacco filter innovations that grow market share, appeal to youth and perpetuate misperceptions of reduced harm should be targets for regulation. The tobacco industry cannot claim that these flavour technologies are long-held trade secrets, and therefore arguments against banning them may be weaker than arguments used to undermine bans of flavours added to the tobacco leaf.

The appeal of flavoured tobacco for youth and misperceptions of reduced risk from menthol-flavoured tobacco have supported a variety of efforts to ban menthol in tobacco products, including unsuccessful efforts in countries such as Chile and Brazil.14 However, some jurisdictions have made meaningful progress. For example, the European Union's Tobacco Product Directive will implement a ban of menthol and flavour capsules, starting in 2019.15 In Canada, local jurisdictions banned menthol (ie, Nova Scotia, Alberta, Ontario, Quebec, New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island),14 followed by a federal ban. In the USA, 'characterising flavours' (ie, a flavour term used in advertising or marketing a tobacco product) are banned, but menthol is still permitted. Lenient legal definitions like this nevertheless allow products for which the flavour character is communicated under the guise of a colour or other descriptor, thus undermining the flavour ban (figure 3). Nevertheless, the US Food and Drug Administration recently demanded the removal of one Camel flavour capsule variety (ie, Camel Crush Bold) from the US market, judging that it posed a potential threat to public health and was not 'substantially equivalent' to brands on the market before 2007.16 To help decrease the appeal of smoking among smokers and young experimenters alike, jurisdictions should consider banning flavour capsule varieties and other filter innovations involving flavours, as well as tobacco flavours.

Figure 3.

Example of flavour capsule cigarette pack that includes four different flavors, including. Red Sense, Lemongrass, Mint and Blue Touch.

Footnotes

Contributors JFT initiated and conceived the study with the assistance of FJC, who provided access and advice on the data. FI analysed the data. JFT and FI drafted the manuscript. JB, RM, MTV and FJC provided constructive inputs in the revising of the manuscript. All the authors approved the final draft and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Competing interests None declared.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

REFERENCES

- 1.Klausner K. Menthol cigarettes and smoking initiation: a tobacco industry perspective. Tob Control. 2011;20(Suppl 2):ii12–19. doi: 10.1136/tc.2010.041954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson SJ. Marketing of menthol cigarettes and consumer perceptions: a review of tobacco industry documents. Tob Control. 2011;20:ii20–8. doi: 10.1136/tc.2010.041939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tobacco Products Scientific Advisory Committee . Menthol Cigarettes and Public Health: review of the Scientific Evidence and Recommendations. Tobacco Product Scientific Advisory Committee for the Food and Drug Administration, Department of Health and Human Services; USA: 2011. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/AdvisoryCommittees/CommitteesMeetingMaterials/TobaccoProductsScientificAdvisoryCommittee/UCM269697.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moderator Guide . Crushable Capsules Qual And Quant Testing. RJ Reynolds; Florida: 2002. Intro. (Bates no.: 529931740-529931745) https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/mzmn0187. [Google Scholar]

- 5.British American Tobacco . Annual Report 2014: delivering today, investing in tomorrow. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Euromonitor International . Tobacco: Euromonitor Passport Database. Euromonitor International; London: 2014. http://www.euromonitor.com. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Phillip Morris International . 2014 Annual Report. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barnoya J, Mejia R, Szeinman D, et al. Tobacco point-of-sale advertising in Guatemala City, Guatemala and Buenos Aires, Argentina. Tob Control. 2010;19:338–41. doi: 10.1136/tc.2009.031898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Children targeted by Big Tobacco . In: Fundación Interamericana del Corazón Argentina, Aliança de Controle do Tabagismo. 3rd Edn. Buenos Aires; Argentina: 2015. An analysis of the advertising and display of tobacco products at points of sale in Latin America as a strategy to attract children and adolescents to tobacco use; pp. 38–44. Health is not negotiable. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thrasher JF, Abad-Vivero EN, Moodie C, et al. Cigarette brands with flavour capsules in the filter: trends in use and brand perceptions among smokers in the USA, Mexico and Australia, 2012–2014. Tob Control. 2016;25:275–83. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-052064. http://tobaccocontrol.bmj.com/content/early/2015/05/05/tobaccocontrol-2014-052064.full.pdf+html. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chile Libre de Tabaco . Encuesta sobre consumo de Tabaco Mentolado en Santiago: Chile Libre de Tabaco. Chile Libre de Tabaco; Santiago, Chile: 2015. http://www.chilelibredetabaco.cl/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/Hoja-informativa-estudio-cuanti-mentol-2.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abad-Vivero EN, Thrasher JF, Arillo-Santillán E, et al. Recall, appeal, and willingness to try cigarettes with flavor capsules: assessing the impact of a tobacco product innovation amongst early adolescents. Tob Control. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2015-052805. Published Online First: 8 Apr 2016. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2015-052805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Connolly GN, Behm I, Osaki Y, et al. The impact of menthol cigarettes on smoking initiation among non-smoking young females in Japan. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2011;8:1–14. doi: 10.3390/ijerph8010001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tobacco Control Legal Consortium . How other countries regulate flavored tobacco products. Tobacco Control Legal Consortium; Saint Paul, MN: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Parliament E. Directive 2014/40/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 3 April 2014 on the approximation of the laws, regulations and administrative provisions of the Member States concerning the manufacture, presentation and sale of tobacco and related products and repealing Directive 2001/ 37/EC. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 16.US Food and Drug Administration . FDA issues orders that will stop further U.S. sale and distribution of four R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company cigarette products. 2015. [Google Scholar]