Abstract

BACKGROUND

Thresholds for repair of abdominal aortic aneurysms vary considerably among countries.

METHODS

We examined differences between England and the United States in the frequency of aneurysm repair, the mean aneurysm diameter at the time of the procedure, and rates of aneurysm rupture and aneurysm-related death. Data on the frequency of repair of intact (nonruptured) abdominal aortic aneurysms, in-hospital mortality among patients who had undergone aneurysm repair, and rates of aneurysm rupture during the period from 2005 through 2012 were extracted from the Hospital Episode Statistics database in England and the U.S. Nationwide Inpatient Sample. Data on the aneurysm diameter at the time of repair were extracted from the U.K. National Vascular Registry (2014 data) and from the U.S. National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (2013 data). Aneurysm-related mortality during the period from 2005 through 2012 was determined from data obtained from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the U.K. Office of National Statistics. Data were adjusted with the use of direct standardization or conditional logistic regression for differences between England and the United States with respect to population age and sex.

RESULTS

During the period from 2005 through 2012, a total of 29,300 patients in England and 278,921 patients in the United States underwent repair of intact abdominal aortic aneurysms. Aneurysm repair was less common in England than in the United States (odds ratio, 0.49; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.48 to 0.49; P<0.001), and aneurysm-related death was more common in England than in the United States (odds ratio, 3.60; 95% CI, 3.55 to 3.64; P<0.001). Hospitalization due to an aneurysm rupture occurred more frequently in England than in the United States (odds ratio, 2.23; 95% CI, 2.19 to 2.27; P<0.001), and the mean aneurysm diameter at the time of repair was larger in England (63.7 mm vs. 58.3 mm, P<0.001).

CONCLUSIONS

We found a lower rate of repair of abdominal aortic aneurysms and a larger mean aneurysm diameter at the time of repair in England than in the United States and lower rates of aneurysm rupture and aneurysm-related death in the United States than in England. (Funded by the Circulation Foundation and others.)

The decision about whether to repair an abdominal aortic aneurysm requires consideration of a balance of risks, including aneurysm rupture if surgery is not performed and death due to aneurysm repair itself, as well as consideration of an individual patient’s probable life expectancy. The decision is influenced by patient and clinician preference, medical management of coexisting conditions, and the availability of and access to endovascular procedures as an alternative to open repair. The aneurysm diameter is the best predictor of aneurysm rupture1,2; the risk increases exponentially with an increasing diameter.3 Therefore, the aneurysm diameter is a key determinant of the threshold for intervention.

International guidelines recommend that intervention should be considered once the aneurysm diameter exceeds 55 mm in men or 50 mm in women.4 However, the considerable variation in clinical practice reflects uncertainty regarding the best threshold for intervention. The proportion of aneurysms that are repaired at a diameter of less than 55 mm has been reported to range from 6.4 to 29.0% in various countries.5

The current study aimed to compare the incidence of repair of intact (nonruptured) aneurysms and the aneurysm diameters at the time of repair in England with those in the United States. We sought to examine whether any difference in the threshold for repair of intact aneurysms might be associated with a discrepancy in aneurysm-related mortality between the two countries.

METHODS

STUDY CONDUCT AND OVERSIGHT

The study was designed and the data were gathered and analyzed by all the authors, who made the decision to submit the manuscript for publication and vouch for the accuracy and completeness of the data and all analyses. Funding was provided by the Circulation Foundation and the National Institute for Health Research in the United Kingdom and by the National Institutes of Health in the United States. The funding agencies had no role in the design of the study, the collection and analysis of the data, the preparation of the manuscript, or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

DATA SOURCES FOR ANEURYSM REPAIR, IN-HOSPITAL MORTALITY, AND ANEURYSM RUPTURE

National data on the frequency of repair of intact infrarenal abdominal aortic aneurysms and inhospital mortality among patients who had undergone aneurysm repair were extracted from the Hospital Episode Statistics database in England and the Nationwide Inpatient Sample in the United States. These and other data sources that were used in this study are described in the Supplementary Methods section in the Supplementary Appendix, available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org.

We identified cases of either endovascular or open repair of intact aneurysms between January 1, 2005, and December 31, 2012, by a search for patients who had an elective admission associated with codes for endovascular or open repair of an aneurysm in the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10), or Office of Population Censuses and Surveys Classification of Interventions and Procedures, version 4, in the Hospital Episode Statistics database and with relevant codes in the International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification in Nationwide In-patient Sample data. Identification involved the use of published methods6 (described in the Supplementary Methods section and Table S1 in the Supplementary Appendix).

For the same study period, the Hospital Episode Statistics database was used to determine the frequency of hospital admissions for a ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm in England. The Nationwide Inpatient Sample was used to determine the same information in the United States. Previously published methods7 (described in the Supplementary Methods section in the Supplementary Appendix) were used to determine the frequency of hospital admissions.

DATA SOURCES FOR LONG-TERM SURVIVAL AND ANEURYSM-RELATED MORTALITY

Data on long-term survival among patients who had undergone repair of abdominal aortic aneurysms between January 1, 2005, and December 31, 2008, were obtained, and follow-up data were censored on December 31, 2009. Representative U.S. data were obtained by identifying all traditional Medicare beneficiaries who had undergone elective endovascular or open repair of abdominal aortic aneurysms, according to previously published selection criteria and coding methods8 (described in the Supplementary Methods section in the Supplementary Appendix). Data on patients in England were obtained from the Hospital Episode Statistics database, as described above.

Data on the frequency of aneurysm-related deaths during the period from 2005 through 2012 in the United States were obtained from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (www.cdc.gov), and those data in England were obtained from the Office of National Statistics (www.ons.gov.uk). Aneurysm-related death in both countries was defined as death associated with the causes recorded with the ICD-10 codes listed in Table S1 in the Supplementary Appendix.

DATA SOURCES FOR ANEURYSM DIAMETER AND COVARIATE RISK FACTORS

Descriptive data on the preoperative maximum aneurysm diameter at the time of elective repair in patients in England were obtained from the National Vascular Registry for the period from January through December 2014; data on patients in the United States were obtained from the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP) for the period from January through December 2013. Data on the prevalence of abdominal aortic aneurysms at each diameter among men in England during the period from 2009 through 2014 were extracted from the National Health Service Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Screening Programme (NAAASP).

Data on the prevalence of smoking, hypercholesterolemia, and hypertension were obtained with the use of previously published methods9 (described in the Supplementary Methods section and Table S1 in the Supplementary Appendix). Data on the prevalence of smoking during the period from 2001 through 2005 were extracted from the International Mortality and Smoking Statistics database (version 4.12), and data on the prevalence of hypertension, the use of lipid-lowering medication, and the prevalence of hypercholesterolemia during the period from 2005 through 2010 were obtained from the World Health Organization Global InfoBase. Because of systematic differences in coding policies between the United States and England and the likelihood of resulting ascertainment bias, data on coexisting conditions from the Hospital Episode Statistics database, Medicare, and the Nationwide Inpatient Sample were not used for risk adjustment.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

The direct standardization method was used to adjust for differences in age and sex between England and the United States for annual data on the frequency of repair of intact aneurysms, hospitalizations for aneurysm rupture, and aneurysm-related deaths. Study cohorts were stratified according to sex and 5-year age group. Cohorts in England were standardized with reference to the 2011 Office of National Statistics census data, and cohorts in the United States were standardized with reference to the 2010 U.S. Census Bureau data (www.census.gov).

A conditional logistic-regression analysis was performed. This analysis incorporated the age and sex strata as blocking variables in the calculation of the adjusted difference between England and the United States with respect to the incidence of repair of intact aneurysms, hospitalizations for aneurysm rupture, and aneurysm-related deaths. A sensitivity analysis was performed to investigate whether the discrepancy in aneurysm-related mortality between the United States and England might have been partly related to differences in the prevalence of smoking, hypercholesterolemia, or hypertension. Survival was characterized with the use of the Kaplan–Meier method and compared between countries by means of a Cox proportional-hazards model that incorporated adjustment for age, sex, year of surgery, and type of repair procedure (endovascular or open).

For the analysis of aneurysm diameter, crude means were reported for each country, and population-weighted means were calculated. A conditional regression analysis incorporating age, sex, and country of repair was used to assess the difference in aneurysm diameter at the time of repair between England and the United States and to test for statistical significance.

To model the potential effect of U.S. thresholds for aneurysm repair on rates of repair of intact aneurysms in England, data on the size of aneurysms at the time of repair were used to derive a standardized incidence of aneurysm repair per 100,000 men in the United States. Diameter-specific prevalence data from the NAAASP were then used to determine the expected standardized rate of aneurysm repair at each aneurysm diameter in England if England adopted U.S. rates of repair. All analyses were performed with the use of SAS software, version 9.3 (SAS Institute), and Stata software, version 12.0 (StataCorp).

RESULTS

FREQUENCY OF ANEURYSM REPAIR

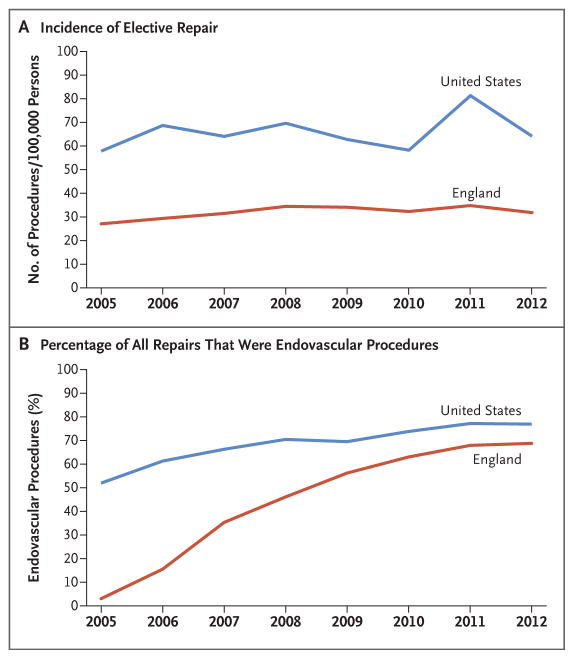

During the period from 2005 through 2012, a total of 29,300 patients underwent repair of intact abdominal aortic aneurysms in England (according to the Hospital Episode Statistics data), as compared with an estimated 278,921 patients who underwent repair of intact abdominal aortic aneurysms in the United States (according to the Nationwide Inpatient Sample data). The incidence of repair of intact aneurysms in England increased from 27.11 procedures per 100,000 persons in 2005 to 31.85 per 100,000 in 2012 (Fig. 1A). During the same period, the incidence of repair of intact aneurysms in the United States increased from 57.85 procedures per 100,000 persons in 2005 to 64.17 per 100,000 in 2012.

Figure 1. Repair of Intact Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms in England and the United States, 2005–2012.

Shown are the incidence of repair of intact abdominal aortic aneurysms (Panel A) and the percentage of all repairs of intact abdominal aortic aneurysms that were endovascular procedures (Panel B). Data on patients in England are from the Hospital Episode Statistics database, and data on patients in the United States are from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample.

Across all study years and after standardization for population age and sex, repair of intact aneurysms was significantly less common per 100,000 population in England than in the United States (odds ratio, 0.49; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.48 to 0.49; P<0.001) (Table S2A in the Supplementary Appendix). Overall during the study, the percentage of repairs of intact aneurysms that were endovascular procedures was lower in England than in the United States (45.5% vs. 67.0%, P<0.001). This lower rate persisted in 2012 despite an increase in endovascular repair procedures in England over time (the percentages of repairs that were endovascular procedures in 2012 were 67.2% in England vs. 75.4% in the United States, P<0.001 [Fig. 1B]).

IN-HOSPITAL MORTALITY AND LONG-TERM SURVIVAL

Overall, in-hospital mortality among patients who had undergone aneurysm repair was 2.6% in England as compared with 1.8% in the United States (0.9% vs. 0.8% among patients who had undergone endovascular repair and 4.1% vs. 4.0% among patients who had undergone open repair). After standardization for the method of repair, age, sex, and year of surgery, there was no significant difference in in-hospital mortality between England and the United States (odds ratio, 1.04; 95% CI, 0.96 to 1.12; P = 0.40).

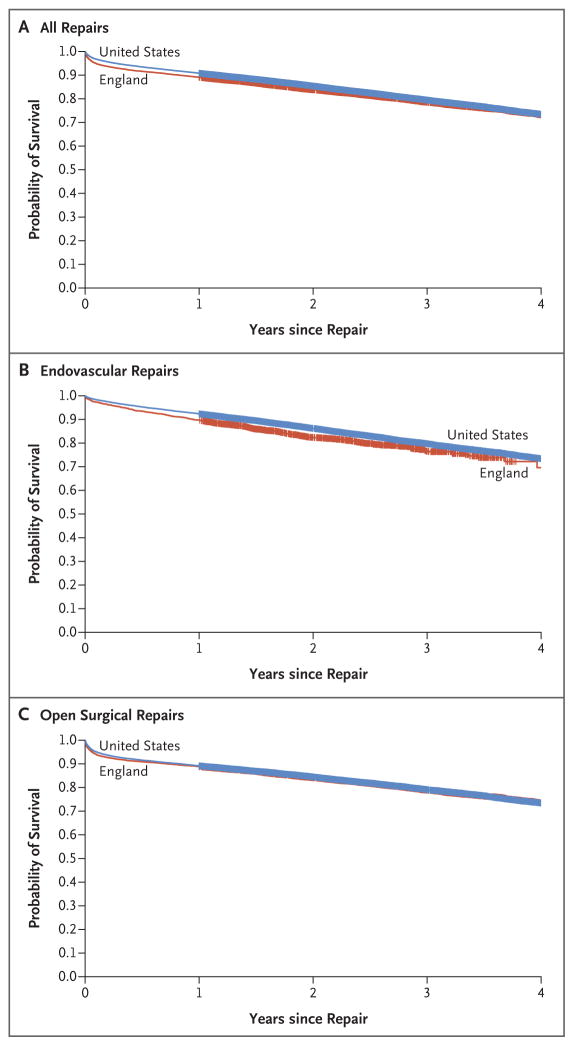

Among 11,409 patients who had undergone aneurysm repair in England and 34,073 Medicare patients who had undergone aneurysm repair in the United States during the period from 2005 through 2008, the rate of 3-year survival was 78.5% in England versus 79.5% in the United States (76.6% vs. 79.8% among patients who had undergone endovascular repair and 78.1% vs. 79.1% among patients who had undergone open repair) (Fig. 2). After adjustment for age, sex, year of surgery, and endovascular versus open repair, there was no significant difference in the rate of 3-year survival between patients who had undergone aneurysm repair in England and those who had undergone this procedure in the United States (hazard ratio for death, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.92 to 1.02; P = 0.17).

Figure 2. Kaplan–Meier Estimates of 3-Year Survival after Repair of Intact Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms in England and the United States, 2005–2008.

Shown are survival curves after all repairs (Panel A), after endovascular repair (Panel B), and after open surgical repair (Panel C) of intact abdominal aortic aneurysms. Data on patients in England are from the Hospital Episode Statistics database, and data on patients in the United States are from Medicare.

ANEURYSM RUPTURE

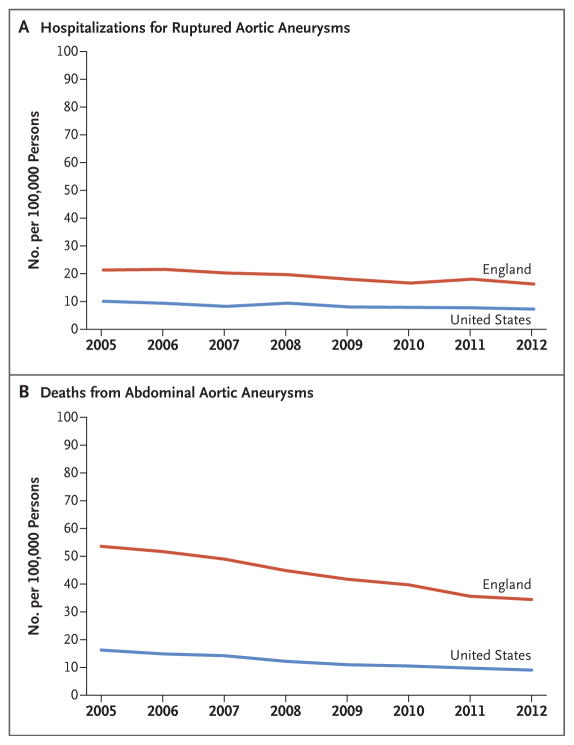

During the period from 2005 through 2012, a total of 17,253 patients in England and 35,922 patients in the United States were hospitalized for aneurysm rupture. The incidence decreased from 21.34 hospitalizations due to aneurysm rupture per 100,000 population in England in 2005 to 16.30 per 100,000 in 2012 (Fig. 3A). During the same period, the incidence in the United States decreased from 10.10 hospitalizations due to aneurysm rupture per 100,000 population in 2005 to 7.29 per 100,000 in 2012. Across all study years and after standardization for population age and sex, hospitalization due to aneurysm rupture was significantly more common in England than in the United States (odds ratio, 2.23; 95% CI, 2.19 to 2.27; P<0.001) (Table S2B in the Supplementary Appendix).

Figure 3. Incidence of Hospitalization and Death due to Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms in England and the United States, 2005–2012.

Panel A shows the incidence of hospitalization for ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms. Data on patients in England are from the Hospital Episode Statistics database, and data on patients in the United States are from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample. Panel B shows the number of deaths related to abdominal aortic aneurysms. Data on patients in England are from the Office of National Statistics, and data on patients in the United States are from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

ANEURYSM-RELATED DEATH

During the period from 2005 through 2012, a total of 39,740 aneurysm-related deaths occurred in England, as compared with 51,475 aneurysm-related deaths in the United States. The incidence decreased from 53.55 aneurysm-related deaths per 100,000 persons in England in 2005 to 34.43 per 100,000 in 2012 (Fig. 3B). Over the same period, aneurysm-related deaths decreased in the United States from 16.24 per 100,000 persons in 2005 to 9.03 per 100,000 in 2012.

Across all study years and after standardization for population age and sex, aneurysm-related death was significantly more common in England than in the United States (odds ratio, 3.60; 95% CI, 3.55 to 3.64; P<0.001) (Table S2C in the Supplementary Appendix). After a sensitivity analysis that included adjustment for the prevalence of smoking, hypertension, and hypercholesterolemia, aneurysm-related death remained significantly more common in England than in the United States (odds ratio, 3.54; 95% CI, 3.33 to 3.76; P<0.001).

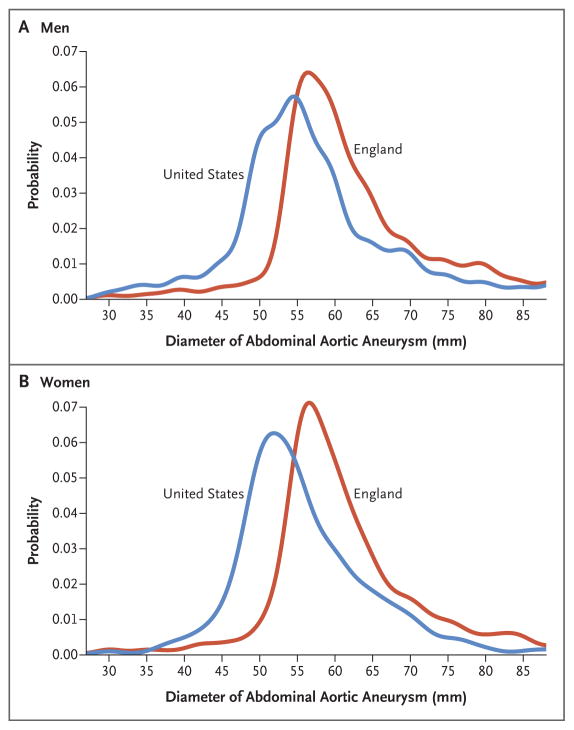

ANEURYSM DIAMETER AT THE TIME OF REPAIR

According to the National Vascular Registry, during the period from January through December 2014, a total of 4128 patients in England (12% female) underwent repair of intact aneurysms, with a mean (±SD) maximum preoperative aneurysm diameter of 63.8±12.7 mm (64.1±12.9 mm in men and 61.7±10.8 mm in women) (Table S3 in the Supplementary Appendix). Endovascular repair was performed at a significantly lower diameter than open repair, and more men than women underwent repair below the recommended threshold (Table S3 in the Supplementary Appendix).

According to the NSQIP, during the period from January through December 2013, a total of 2598 patients in the United States (21% female) underwent repair of intact aneurysms, with a mean maximum preoperative aneurysm diameter of 58.2±13.2 mm (58.6±13.4 mm in men and 56.3±12.0 mm in women) (Table S3 in the Supplementary Appendix). Endovascular repair was performed at a significantly lower diameter than open repair, and more men than women underwent repair below the recommended threshold (Table S3 in the Supplementary Appendix).

With the use of population weighting for age and sex, the weighted mean diameter of abdominal aortic aneurysms at the time of repair was 63.7 mm in England, as compared with 58.3 mm in the United States. After adjustment for age, sex, and endovascular versus open repair, there remained a significant discrepancy in the diameter of repaired aneurysms; intact aneurysms at the time of repair in England were a mean (±SE) of 5.3±0.3 mm larger than intact aneurysms at the time of repair in the United States (P<0.001) (Fig. 4, and Fig. S1 in the Supplementary Appendix).

Figure 4. Diameter of Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms at the Time of Repair in England in 2014 and in the United States in 2013.

Shown are probability density function curves of the diameter of abdominal aortic aneurysms at the time of repair in men (Panel A) and women (Panel B). Data on patients in England are from the U.K. National Vascular Registry, and data on patients in the United States are from the U.S. National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP).

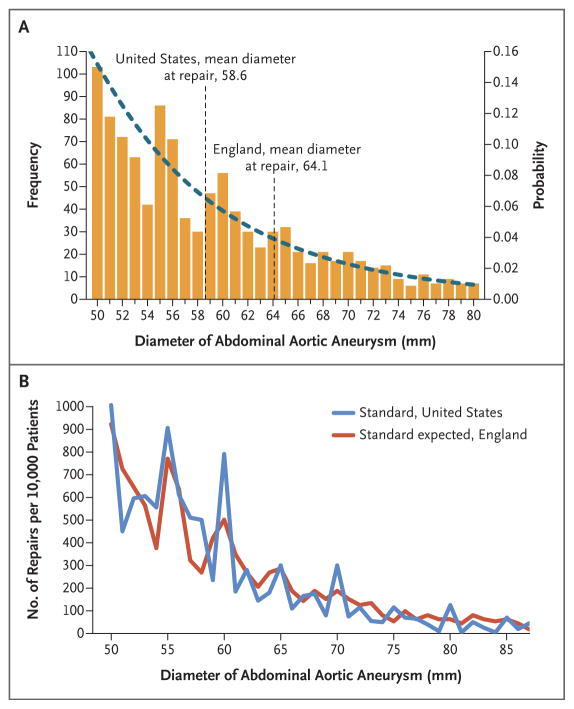

Data from the NAAASP on aneurysm screening in England showed that smaller aneurysms were significantly more common than larger aneurysms (Fig. 5A). Among the first 700,000 men enrolled (during the period from April 2009 through August 2014), 76 men per 100,000 men screened presented with aneurysms at or above the mean diameter for repair in the United States (58.6 mm), as compared with 48 men per 100,000 who presented with aneurysms at or above the mean diameter for repair in England (64.1 mm).

Figure 5. Diameter of Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms and Number of Repairs in England and the United States.

Panel A shows a frequency histogram and probability density function distribution for the diameter of abdominal aortic aneurysms among the first 700,000 men screened in England. This screening occurred between April 2009 and August 2014. A total of 48 men per 100,000 men screened had aneurysms at or above the mean diameter for aneurysm repair in England, as compared with 76 men per 100,000 screened who had aneurysms at or above the mean diameter for aneurysm repair in the United States. Panel B shows the standardized numbers of repairs of abdominal aortic aneurysms in the United States as compared with the expected numbers of repairs of abdominal aortic aneurysms in England. The results are shown after application of the U.S. probability density for repair at various aortic diameters to the prevalence data for abdominal aortic aneurysms in England at each diameter in the U.K. national screening program. Data on patients in England are from the National Health Service Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Screening Programme, and data on patients in the United States are from the NSQIP.

The application of U.S. thresholds for aneurysm repair to the proportion of aneurysms at each screened diameter in the NAAASP would result in a left shift of the probability distribution for aneurysm repair in England (Fig. S2 in the Supplementary Appendix). Among men with aneurysms larger than 50 mm in diameter, the application of U.S. probabilities for aneurysm repair at a given aortic diameter to aneurysm prevalence rates according to the diameter derived from the screening program in England results in an expected probability of aneurysm repair in England that would be equivalent to the distribution of repair at a given aortic diameter in the United States (P = 0.17 by the Kruskal–Wallis test) (Fig. 5B).

DISCUSSION

This study showed that among patients with intact (nonruptured) abdominal aortic aneurysms, the rate of repair over an 8-year period was half as high in England as in the United States. Other data (from two different years) indicated that there was also a difference between the two countries in the mean aneurysm diameter at the time of repair, with an adjusted difference of 5.3 mm. National screening data for England suggest that these two observations may be related, because the prevalence of aneurysms at the mean diameter for repair in the United States was almost twice as high as the prevalence of aneurysms at the mean diameter for repair in England. In addition, we found that endovascular repair was used less frequently in England than in the United States, and endovascular repairs were performed at lower aneurysm diameters (in both countries) than open repair.

Among patients who were selected for aneurysm repair, in-hospital mortality and the rates of 3-year survival were similar in England and the United States. This finding suggests that the increased rate of aneurysm repair in the United States did not come at the expense of greater perioperative or postoperative risk. However, two observations from our data suggest that the lower rate of aneurysm repair in England may have adverse consequences. Although the rate of hospitalization due to aneurysm rupture decreased in both countries over the 8 years studied, this rate was more than twice as high in England as in the United States. In addition, although aneurysm-related mortality also decreased over time in both countries, this rate was 3.5 times as high in England as in the United States.

The rates of aneurysm repair and of aneurysm-related death were derived from separate data sets in both countries, and we have not shown a causal association between the two. Nonetheless, these observations, based on the same time period, suggest the possibility of a causal relationship and raise the question of whether outcomes in England would be improved if the repair thresholds used in the United States were adopted.

Previous clinical trials have suggested that survival among patients with aneurysms smaller than 55 mm in diameter was the same regardless of whether they underwent immediate repair or imaging surveillance and delayed repair.10–13 However, all these trials began recruitment at least a decade ago, and clinical practice has changed considerably since then.8,14–17 It has been suggested that the size threshold for aneurysm repair should be revisited,18 and this presumably would require new clinical trials.

The current study was limited by the available national data sets in England and the United States. Aneurysm diameters were analyzed at different time windows in England (2014) and the United States (2013) because of the availability of data. Information regarding cause of death was extracted from governmental population-weighted data sets (from the CDC and the Office of National Statistics), which potentially precluded complete case ascertainment of all deaths within 30 days after aneurysm surgery or deaths as a result of reinterventions for repair of aneurysms within the definition of “aneurysm-related mortality.” Autopsy rates are low in both the United States and England, so it is difficult to definitively confirm government data on mortality due to aneurysm rupture. The contemporary diameter-specific prevalence of repair was available only for male patients through national screening initiatives; this precluded modeling of the potential effect of threshold changes on the prevalence of repair among women.

Although analyses were adjusted for age, the age distribution at the time of repair in the United States showed a left shift as compared with the distribution in England; this also reflects the lower diameter at the time of repair in patients in the United States (Fig. S3 in the Supplementary Appendix). However, the age discrepancy was not large enough to explain the observed differences in the rates of aneurysm repair, aneurysm rupture, and death. Screening data suggest that the prevalence of aneurysms is similar in England and the United States, so it is unlikely that differences in the underlying prevalence of disease influenced the results of this study. The estimated prevalence of aneurysms larger than 30 mm in diameter is 1.4% among 3.1 million patients between 50 and 84 years of age in the United States,19 as compared with 1.3% according to contemporaneous NAAASP data on patients in England.

In conclusion, we compared data on abdominal aortic aneurysm repair in England with those data in the United States. In the United States, rates of aneurysm repair were twice as high as those in England over the period studied, and aneurysm repair was performed at a lower mean aneurysm diameter. Rates of aneurysm rupture and aneurysm-related death were significantly higher in England than in the United States.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by the Circulation Foundation, the United Kingdom National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), a Circulation Foundation Surgeon Scientist Award (to Dr. Karthikesalingam), an NIHR Clinician Scientist Award (NIHR-CS-011-008, to Dr. Holt), a grant from the NHLBI (5R01HL105453-03, to Dr. Schermerhorn), and an NIH T32 Harvard–Longwood Research Training in Vascular Surgery grant (HL007734, to Dr. Soden).

Footnotes

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the National Institute for Health Research, the National Health Service, or the Department of Health.

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org.

Drs. Loftus and Thompson report receiving consulting fees from Endologix, Medtronic, and Gore and grant support to their institution from Endologix and Medtronic; and Dr. Schermerhorn, receiving fees for serving on a data and safety monitoring board from Endologix and consulting fees from Endologix and Cordis. No other potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Brown LC, Powell JT. Risk factors for aneurysm rupture in patients kept under ultrasound surveillance. Ann Surg. 1999;230:289–96. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199909000-00002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brady AR, Thompson SG, Fowkes FG, Greenhalgh RM, Powell JT. Abdominal aortic aneurysm expansion: risk factors and time intervals for surveillance. Circulation. 2004;110:16–21. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000133279.07468.9F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lederle FA, Johnson GR, Wilson SE, et al. Rupture rate of large abdominal aortic aneurysms in patients refusing or unfit for elective repair. JAMA. 2002;287:2968–72. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.22.2968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moll FL, Powell JT, Fraedrich G, et al. Management of abdominal aortic aneurysms clinical practice guidelines of the European Society for Vascular Surgery. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2011;41(Suppl 1):S1–S58. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2010.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mani K, Venermo M, Beiles B, et al. Regional differences in case mix and peri-operative outcome after elective abdominal aortic aneurysm repair in the Vascunet database. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2015;49:646–52. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2015.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Karthikesalingam A, Holt PJ, Vidal-Diez A, et al. The impact of endovascular aneurysm repair on mortality for elective abdominal aortic aneurysm repair in England and the United States. J Vasc Surg. 2016;64(2):321–327. e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2016.01.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Karthikesalingam A, Holt PJ, Vidal-Diez A, et al. Mortality from ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms: clinical lessons from a comparison of outcomes in England and the USA. Lancet. 2014;383:963–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60109-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schermerhorn ML, Buck DB, O’Malley AJ, et al. Long-term outcomes of abdominal aortic aneurysm in the Medicare population. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:328–38. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1405778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sidloff D, Stather P, Dattani N, et al. Aneurysm global epidemiology study: public health measures can further reduce abdominal aortic aneurysm mortality. Circulation. 2014;129:747–53. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.005457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lederle FA, Wilson SE, Johnson GR, et al. Immediate repair compared with surveillance of small abdominal aortic aneurysms. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1437–44. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Powell JT, Brown LC, Forbes JF, et al. Final 12-year follow-up of surgery versus surveillance in the UK Small Aneurysm Trial. Br J Surg. 2007;94:702–8. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cao P, De Rango P, Verzini F, et al. Comparison of surveillance versus Aortic Endografting for Small Aneurysm Repair (CAESAR): results from a randomised trial. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2011;41:13–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2010.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ouriel K, Clair DG, Kent KC, Zarins CK. Endovascular repair compared with surveillance for patients with small abdominal aortic aneurysms. J Vasc Surg. 2010;51:1081–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2009.10.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holt PJ, Poloniecki JD, Khalid U, Hinchliffe RJ, Loftus IM, Thompson MM. Effect of endovascular aneurysm repair on the volume-outcome relationship in aneurysm repair. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2009;2:624–32. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.109.848465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dimick JB, Upchurch GR., Jr Endovascular technology, hospital volume, and mortality with abdominal aortic aneurysm surgery. J Vasc Surg. 2008;47:1150–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2008.01.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.De Martino RR, Hoel AW, Beck AW, et al. Participation in the Vascular Quality Initiative is associated with improved perioperative medication use, which is associated with longer patient survival. J Vasc Surg. 2015;61:1010–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2014.11.073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schermerhorn ML, Bensley RP, Giles KA, et al. Changes in abdominal aortic aneurysm rupture and short-term mortality, 1995–2008: a retrospective observational study. Ann Surg. 2012;256:651–8. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31826b4f91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paraskevas KI, Mikhailidis DP, Veith FJ. The rationale for lowering the size threshold in elective endovascular repair of abdominal aortic aneurysm. J Endovasc Ther. 2011;18:308–13. doi: 10.1583/10-3371.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kent KC, Zwolak RM, Egorova NN, et al. Analysis of risk factors for abdominal aortic aneurysm in a cohort of more than 3 million individuals. J Vasc Surg. 2010;52:539–48. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2010.05.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.