Abstract

Objectives: Inappropriately decreased heart rate (HR) during peak exercise and delayed heart rate recovery (HRR) has been observed in adult users of stimulant medications who underwent exercise testing, suggesting autonomic adaptation to chronic stimulant exposure. In the general population, this pattern of hemodynamic changes is associated with increased mortality risk. Whether the same pattern of hemodynamic changes might be observed in adolescent stimulant medication users undergoing exercise testing is unknown.

Methods: Among adolescents (aged 12 to 20 years) that underwent submaximal exercise treadmill testing from 1999 to 2004 in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, propensity score matching of stimulant medication users (n = 89) to matched nonusers (n = 267) was conducted. Testing consisted of a 3-minute warm-up period, two 3-minute exercise stages, and three 1-minute recovery periods, with the goal of reaching 75% of the predicted HR maximum. A linear mixed model analysis was used to evaluate the effect of stimulant exposure on each of the exercise outcomes.

Results: Stimulant medication users compared to matched nonusers had a lower peak HR in Stage 2 (154.9 vs. 158.3 beats/minute [bpm], p = 0.055) and lower HR at 1-minute recovery (142.2 vs. 146.4 bpm, p = 0.030). However, submaximal HRR at 1 minute did not differ between stimulant users and matched nonusers (13.0 vs. 12.1 bpm, p = 0.38). Duration of stimulant use was not related to these outcomes.

Conclusion: Adolescent stimulant medication users compared to matched nonusers demonstrated a trend toward decreased HR during submaximal exercise, which is potential evidence of chronic adaptation with stimulant exposure. There was no evidence for delayed HRR in this study, and thus, no evidence for decreased parasympathetic activity during initial exercise recovery. Exercise testing outcomes may have utility in future research as a method to assess stimulant-associated autonomic nervous system adaptations.

Keywords: : stimulants, cardiovascular, exercise, ADHD, amphetamine, methylphenidate

Introduction

Stimulants and other attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) medications are the most commonly prescribed class of psychotropic medication for youth in the United States (Olfson et al. 2014), with 9% of all boys aged 12 to 18 years taking an ADHD drug (Express Scripts 2014). Concern about the cardiovascular safety of stimulant medication use has focused on modest increases in observed heart rate (HR) and blood pressure (BP) (Stowe et al. 2002; Samuels et al. 2005; Mick et al. 2013). Population-based epidemiological studies have addressed concerns about the cardiovascular safety of stimulant medication use. Increased risk of serious cardiovascular events was not observed in a large cohort of children and young adults (aged 2 to 24 years) taking an ADHD drug (Cooper et al. 2011). Likewise, in a study of children 3 to 17 years, no increased risk of sudden death or ventricular arrhythmia, stroke, or all-cause death was associated with ADHD drug use (Schelleman et al. 2011). Among adults aged 25 to 64 years, no increased risk of serious cardiovascular events was detected among ADHD drug users (Habel et al. 2011). Alternatively, a cohort of all children born in Denmark between 1990 and 1999 demonstrated a twofold increased hazard of a cardiovascular disease diagnosis in stimulant users (Dalsgaard et al. 2014). In adults, an almost twofold increased risk of sudden death or ventricular arrhythmia and all-cause death was associated with methylphenidate use (Schelleman et al. 2012).

Regarding mechanisms of cardiovascular risk, researchers have largely focused on increases in observed HR and BP. A meta-analysis of adult stimulant medication clinical trials demonstrated increases in resting HR (+5.7 beats/minute [bpm]) and systolic blood pressure (SBP; +2.0 mmHg). Using 24-hour ambulatory BP monitoring, studies have been able to show HR and BP increases in children who are prevalent users of stimulant medications (Stowe et al. 2002; Samuels et al. 2005). A 10-year naturalistic study of children on stimulant medications showed increased HR, but no BP differences compared to never-medicated children (Vitiello et al. 2012). A 2-year study of adults on stimulants showed the same pattern—increased HR, but unchanged BP when comparing baseline measures to study end (Bejerot et al. 2010). However, focusing solely on measured increases in HR and BP ignores the underlying phenomenon of sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous system adaptation secondary to chronic stimulant use (we define acute and chronic use as the periods of use characterized by acute and chronic physiologic adaptation, respectively). For example, a study of 85 children and adolescents with ADHD currently taking stimulants matched to non-ADHD sibling controls demonstrated decreased heart rate variability (HRV) among the stimulant users (Kelly et al. 2014). The importance of this observation is that decreased HRV (i.e., decreased parasympathetic activation) is associated with increased risk of arrhythmia and sudden death (Algra et al. 1993).

The autonomic nervous system regulates HR and BP changes during and after exercise. Abnormalities of hemodynamic parameters during and after maximal exercise testing have been found to predict serious cardiovascular events. Chronotropic incompetence—defined as inappropriately low HR during activity demands—is associated with increased mortality risk (Lauer et al. 1996; Brubaker and Kitzman 2011). Delayed heart rate recovery (HRR) and SBP recovery after the cessation of maximal exercise are also associated with increased mortality risk (Nishime et al. 2000; Huang et al. 2008). Our prior study of adults (mean age 42 years) in the Cooper Center Longitudinal Study cohort demonstrated that stimulant medication users (n = 245) compared to matched nonusers (n = 735) had lower peak HR during maximal exercise testing and a threefold increased odds of chronotropic incompetence (Westover et al. 2015). In addition, stimulant medication users had nearly a twofold increased odds of delayed HRR and SBP recovery (Westover et al. 2016). These findings are consistent with a “chronic systemic stress syndrome,” chronic heart failure being the best known example, which is characterized by elevated catecholamine circulation, downregulation of cardiac beta receptors, and decreased parasympathetic activation (Pierpont et al. 2013). These findings, if confirmed, suggest that maximal exercise testing may have a role in assessing autonomic changes secondary to stimulant use and serve as an intermediate outcome to serious cardiovascular events. Thus, exercise testing could provide a way to evaluate cardiovascular risk among chronic users of stimulant medication in both clinical and research settings.

In this study of adolescents who underwent submaximal exercise treadmill testing, we sought to determine whether stimulant medication users differed from matched nonusers on HR and SBP during and after exercise. We hypothesized that adolescent stimulant users compared to matched nonusers would demonstrate the same pattern of results that was previously observed in adults—that is, stimulant users compared to matched nonusers would have decreased HR during peak exercise and 1-minute recovery, delayed submaximal HRR at 1-minute recovery, and no difference in SBP during peak exercise (Westover et al. 2015, 2016).

Methods

Study design and study population

This propensity-score matched cross-sectional design consisted of subjects enrolled in the continuous National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) from 1999 to 2004. NHANES is a nationally representative sample of about 5000 persons per year who undergo a detailed interview and examination process in counties across the United States. Submaximal treadmill exercise testing was conducted from 1999 to 2004. This research was approved by the NHANES Ethics Review Board. Informed consent/assent was obtained from all participants. Parent/guardian consent was obtained for all participants under 18 years who were not emancipated minors.

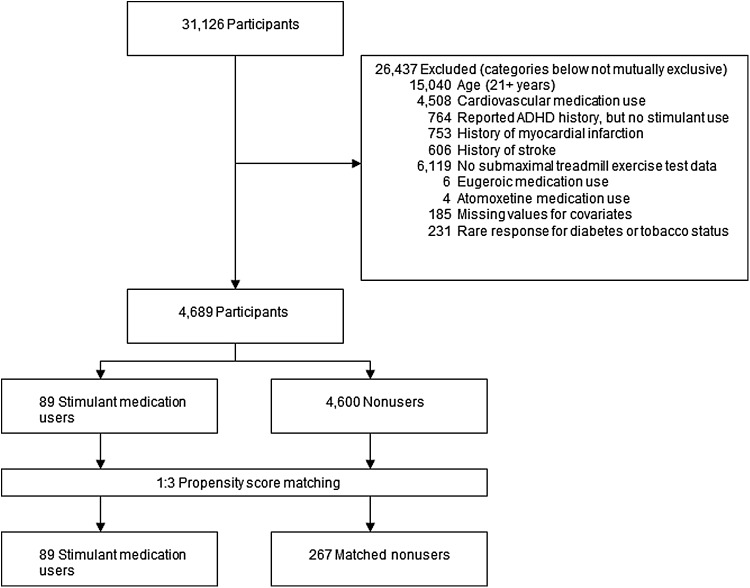

Some 31,126 participants were considered for study inclusion (Fig. 1). Participants who reported using medications classified as “Cardiovascular Agents” (including antihypertensives), atomoxetine, or eugeroics (e.g., modafinil) were excluded. Participants reporting a history of stroke or myocardial infarction were excluded. Participants reporting a history of ADHD, but no use of stimulants, were excluded due to the possibility of former stimulant use and confounding-by-contraindication. NHANES subjects who did not participate in the submaximal fitness examination (defined as having no data for Stage 1 and 1-minute recovery) were excluded. Due to the lack of adult stimulant medication users in NHANES, participants 21 years of age or older were excluded. Participants with missing information for education status, body mass index (BMI), and self-reported diabetes mellitus were excluded. Participants with the following very rare responses were also excluded—diabetes status reported as “borderline” or “don't know” (n = 226) and tobacco/nicotine status reported as “refused” or “don't know” (n = 5). After exclusions, 4689 adolescents aged 12 to 20 years were available for propensity score matching.

FIG. 1.

Inclusion, exclusion, and propensity score matching of participants in the NHANES cohort. ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; NHANES, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.

Procedures and measures

Stimulant exposure

NHANES participants (and proxy respondents for those 16 years or younger) reported all medications taken in the past month as part of the survey. Medications defined as stimulants were amphetamine, dextroamphetamine, methamphetamine, phentermine, benzphetamine, phendimetrazine, diethylpropion, mazindol, fenfluramine, methylphenidate, pemoline, amphetamine/dextroamphetamine, dexmethylphenidate, and lisdexamfetamine. Participants reporting use of a stimulant medication were classified as stimulant users (n = 89). The only stimulants included in this sample were amphetamine/dextroamphetamine (n = 35), methylphenidate (n = 53), and phentermine (n = 1). All other participants not reporting stimulant use were classified as nonusers (n = 4600). Duration of use was reported. Dosage was unavailable.

Exercise testing

Each participant underwent a submaximal treadmill exercise test conducted by trained technicians (National Center for Health Statistics 2004). Submaximal testing, rather than maximal testing, was selected for reasons of feasibility. Testing was conducted using programmable Quinton MedTrack ST65 treadmills, which were calibrated weekly. A Colin STBP-780 automatic monitor was used to assess HR (four electrodes) and BP (cuff) and was calibrated weekly using a mercury manometer. On the basis of age, gender, BMI, and self-reported physical activity level, each subject was assigned one of eight treadmill test protocols developed specifically for this exercise test (coded 1 to 8)—the first protocol being the least difficult and the eighth protocol being the most difficult (steeper grades and faster speeds). During a 2-minute warm-up period, participants were expected to reach 50%–60% of predicted maximum HR. If the HR achieved during warm-up was <50%, the next highest exercise protocol was assigned. If the warm-up HR was >60%, the next lowest exercise protocol was assigned. Warm-up was followed by 3-minute-long Stage 1, where HR was expected to reach 60%–75% maximum, and then 3-minute-long Stage 2, where HR was expected to reach 70%–80% maximum. This was followed by a recovery stage consisting of three 1-minute periods. HR and BP were measured at the end of warm-up, stages 1 and 2, and each of the three recovery periods. The exercise protocol itself contained several exclusions, including pregnancy, previous myocardial infarction or stoke, use of beta blockers, calcium channel blockers, ephedrine, ephedra or phentermine, and others (described in Discussion section).

Outcome variables

The primary outcomes for this study were HR and SBP parameters at the peak of exercise (stage 2) and the beginning of exercise recovery (1-minute recovery): Stage 2 HR, stage 2 SBP, 1-minute recovery HR, 1-minute submaximal HRR (defined as stage 2 HR–first minute recovery HR), and 1-minute recovery SBP. Secondarily we reported on HR and SBP measures for nonpeak exercise (i.e., warm-up and stage 1) and 2- and 3-minute recovery, as well as perceived exertion during warm-up, stage 1, and stage 2. Outcomes and definitions were selected a priori. SBP recovery (ratio of third-minute recovery SBP to first-minute recovery SBP) was not selected as an outcome due to the high level of missingness for 3-minute recovery SBP and HR. Because chronotropic incompetence and HRR and SBP recovery outcomes require maximal exercise testing, we were not able to examine these outcomes in the current study.

Covariates

Covariates were selected a priori. The 12 baseline covariates listed in Table 1 were used for propensity score matching and were also included in all of the analytic mixed models. Self-report of gender, tobacco/nicotine use, history of diabetes mellitus, and education status were binary indicators (yes/no). Education status was dichotomized on the basis of a subject being more than 2 years behind expected grade level (e.g., a 12 year old reporting a fourth grade level or lower). Self-report of baseline physical activity (0–7 scale) was treated as a continuous measure. BMI was log transformed to obtain a more normal distribution. After exclusions were applied, missing values for tobacco/nicotine status were imputed for 3 of 89 stimulant users and 198 of 4600 nonusers (see Statistical analysis section below for a brief description of the multiple imputation methodology used here). Covariates considered, but not included due to very high rates of missingness, were self-report of alcohol use, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, and family history of cardiovascular disease. Use of lipid-lowering medication was not included because zero participants (after study exclusions were applied) reported use. Self-report of ADHD was not included as a covariate because of its high collinearity with stimulant medication use. Diagnostic criteria met, subtype, and date of ADHD diagnosis were not available in the data set.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Stimulant Users and Propensity Score-Matched Nonusers and All Nonusers

| Covariates | Matched nonusers (267) | Stimulant medication users (89) | All nonusers (4600) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Agea | 13.9 (2.04) | 13.9 (1.93) | 15.4 (2.25) |

| Education (behind expected grade level), n (%)b | 28 (10.5) | 8 (9.0 | 461 (10.0) |

| Gender (male), n (%) | 202 (75.7) | 67 (75.3) | 2283 (49.6 |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| Non-Hispanic white | 110 (41.2) | 37 (41.6) | 1092 (23.7) |

| Mexican American | 70 (26.2) | 22 (24.7) | 1709 (37.2) |

| Other Hispanic | 7 (2.6) | 3 (3.4) | 195 (4.2) |

| Non-Hispanic black | 68 (25.5) | 23 (25.8) | 1417 (30.8) |

| Other race (including multiracial) | 12 (4.5) | 4 (4.5) | 187 (4.1) |

| Tobacco/nicotine use in last 5 days, n (%)c | 34 (12.7) | 11 (12.4) | 585 (12.7) |

| History of diabetes, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 19 (0.4) |

| Self-report of baseline physical activity, n (%) | |||

| 0 (little/no physical activity, avoids exertion) | 9 (3.4) | 2 (2.2) | 351 (7.6) |

| 1 (little/no physical activity, occasionally exercises) | 29 (10.9) | 11 (12.4) | 683 (14.8) |

| 2 (10–60 minutes physical activity per week) | 44 (16.5) | 15 (16.9) | 937 (20.4) |

| 3 (>60 minutes physical activity per week) | 87 (32.6) | 24 (27.0) | 1389 (30.2) |

| 4 (heavy physical activity, <30 min/week) | 5 (1.9) | 4 (4.5) | 56 (1.2) |

| 5 (heavy physical activity, 30–60 min/week) | 18 (6.7) | 6 (6.7) | 174 (3.8) |

| 6 (heavy physical activity, 1–3 h/week) | 26 (9.7) | 13 (14.6) | 331 (7.2) |

| 7 (heavy physical activity, >3 h/week) | 49 (18.4) | 14 (15.7) | 679 (14.8) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2)a | 20.8 (4.3) | 20.9 (4.9) | 23.5 (5.44) |

| Resting systolic blood pressure (mm Hg)a | 107.1 (10.5) | 107.2 (10.3) | 109.3 (10.2) |

| Resting diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg)a | 59.9 (12.1) | 58.7 (11.6) | 61.5 (11.8) |

| Resting heart rate (bpm)a | 78.3 (10.7) | 77.4 (12.3) | 74.2 (11.2) |

| NHANES wave, n (%) | |||

| 1999–2000 | 73 (27.3) | 20 (22.5 | 1512 (32.9) |

| 2001–2002 | 88 (33.0) | 31 (34.8) | 1575 (34.2) |

| 2003–2004 | 106 (39.7) | 38 (42.7) | 1513 (32.9) |

Mean (standard deviation).

Age (years) subtracted from reported numeric grade level ≤8 (e.g., a 12 year old who reports a fourth grade level education or less).

Before matching, multiple imputation was performed for stimulant users (n = 3) and nonusers (n = 198) with missing data.

NHANES, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.

Propensity score matching

Propensity score matching is a technique used to create a cohort, where exposure groups are (ideally) balanced on multiple covariates (Rosenbaum and Rubin 1983). Briefly, it consists of the following steps: (1) selecting relevant covariates, (2) creating a logistic regression model using the covariates where the outcome is exposure, (3) estimating a scalar propensity score for each participant from the logistic regression model, (4) and then matching each exposed participant to unexposed participants through their nearest propensity scores. Thus, propensity score matching reduces confounding and potential selection bias by matching on observed covariates that predict exposure status. However, confounding from unobserved variables (or unobserved heterogeneity) can create a “hidden” bias. When successful, this technique creates a match where exposure groups are balanced on the predictive covariates. Thus, for the current study, a propensity score-matched cohort of stimulant users and nonusers was created using the 12 baseline covariates (Table 1). The propensity score, defined as a participant's probability of being exposed to stimulant medications conditional on the 12 observed covariates, was estimated in a logistic regression model (area under curve = 0.795, standard error [SE] = 0.026, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.743 to 0.848). Next, each stimulant user was matched to three nonusers with respect to their propensity scores using the greedy matching algorithm procedure (Bergstralh and Kosanke 2003) through nearest-number matching with a caliper of ±0.11 with no replacement. The average observed absolute user/nonuser propensity score difference was 0.0012 (standard deviation [SD] = 0.0088), indicating a tight match. As shown in Table 1, the 12 baseline covariates among users and matched nonusers were indeed balanced; thus, mitigating confounding on these observed covariates.

Statistical analysis

Demographic and clinical characteristics for stimulant medication users and nonusers were described through the sample mean (SD) for continuous variables and the frequency (percentage) for categorical variables. The two independent sample t-tests were used to examine whether there were differences in exercise protocols assigned and used between stimulant users and matched nonusers. A simple logistic regression analysis was conducted to determine if stimulant medication users compared to all nonusers were more likely to be excluded from participation in exercise testing or halted during exercise testing due to “priority 1” (e.g., chest pain, severe shortness of breath) or “priority 2” stopping criteria (e.g., excessive HR/BP) (National Center for Health Statistics 2004). The denominator for this analysis was those participants (after applying all exclusions except lack of data for Stage 1 and 1-minute recovery) for whom exercise testing was assigned. The unadjusted odds of exclusion from the treadmill testing and the odds of treadmill testing being halted were estimated between users and all nonusers and then tested using the Wald chi-square statistic from the logistic model.

The primary data analysis was a linear mixed model analysis designed to evaluate the effect of stimulant medication exposure on each of the outcomes during the exercise test in the propensity score-matched sample. The respective mixed models were conducted with the 12 covariates included in the model. Restricted maximum likelihood estimation, Type 3 tests of fixed effects, and generalized least squares (LS) were used, with the Kenward–Roger correction applied to the compound symmetry covariance structure. The correlation structure of the matched participants was accounted for in the mixed model analysis by treating each block of matched participants as a random effect.

Sensitivity analyses

The effect of duration of stimulant medication use on each of the five primary outcomes was analyzed in a post hoc sensitivity mixed model analysis similar to that described above. Duration was analyzed as a continuous measure as well as a categorical measure (quartiles and quintiles). Moreover, a post hoc moderator analysis on each of the five primary outcomes was performed through linear mixed models by examining (testing) the interactions between stimulant medication exposure and gender, baseline physical activity, exercise protocol used, and BMI. For this analysis, BMI was categorized as low (z-score < −2), normal (−2 ≤ z-score ≤ +2), and high (z-score > +2) based on gender and age (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2009). To assess a moderator effect, for each moderator variable that interacted with stimulant medication exposure, the LS means for each outcome were estimated at each level of the categorical moderator.

Testing for multicollinearity

To ascertain the presence of any multicollinearity in our linear regression models, we examined the variance inflation factor for each of the 12 covariates in each model. The estimated variance inflation factors for the covariates ranged from 1.01 to 1.53, suggesting that multicollinearity was not present or problematic.

All statistical analyses were performed using SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC). Missing values for the classification variable of tobacco/nicotine status (with an assumed arbitrary missing pattern) were imputed through 100 burn-in iterations using the fully conditional specification method along with the discriminant function of the PROC MI procedure in SAS. The propensity scores were estimated using the PROC LOGISTIC procedure in SAS. The gmatch computational SAS macro was used to implement the propensity score matching (Bergstralh and Kosanke 2003). Finally, the PROC GLIMMIX procedure in SAS was used for the mixed model analyses. The level of significance for all tests was set at α = 0.05 (two-tailed). The false discovery rate (FDR) procedure was implemented to control for false positives over the sets of multiple tests of the main effects for stimulant exposure on each outcome. Cohen's d was also calculated to estimate effect sizes for between-group comparisons (stimulant users vs. matched nonusers) on the exercise outcomes.

Results

Participant characteristics

Stimulant medication users (study exclusions applied; n = 89) compared to all nonusers (study exclusions applied, before matching; n = 4600) were more likely to be younger, male, non-Hispanic white, with lower BMI, and higher baseline physical activity and resting HR (Table 1). In contrast, after the propensity score matching procedure, users and matched nonusers (n = 267) were very similar across the 12 baseline covariates. Perceived exertion during warm-up, stage 1, and stage 2 did not differ between stimulant users and matched nonusers. More than 90% (n = 81) of stimulant medication users reported a diagnosis of ADHD. Because ADHD without stimulant medication use was an exclusion, no matched nonusers reported an ADHD diagnosis.

Each participant was assigned one of eight progressively more difficult treadmill test protocols (coded 1 to 8). The initially assigned exercise protocol was similar in level of difficulty between stimulant users and matched nonusers (mean level of difficulty of 5.27 [SD = 1.14] vs. 5.31 [SD = 1.12], respectively, t(354) = 0.27, p = 0.786). Likewise, the difficulty of exercise protocol actually used in stage 1 and stage 2 did not differ between stimulant users and matched nonusers (Table 2; mean level of difficulty of 5.30 [SD = 1.20] vs. 5.27 [SD = 1.17], respectively, t(354) = 0.21, p = 0.836). At 1-minute recovery, 1 nonuser was missing data for SBP. At 2-minute recovery, HR and SBP were both missing for 1 stimulant user and 9 matched nonusers, and for 30 users and 56 matched nonusers at 3-minute recovery.

Table 2.

Exercise Protocols (1–8) Used During Stage 1 and Stage 2 for Stimulant Medication Users (n = 89) and Matched Nonusers (n = 267)

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exercise protocol used | Stage 1 | Stage 2 | Stage 1 | Stage 2 | Stage 1 | Stage 2 | Stage 1 | Stage 2 | Stage 1 | Stage 2 | Stage 1 | Stage 2 | Stage 1 | Stage 2 | Stage 1 | Stage 2 |

| Speed (mph) | 2.1 | 2.1 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 2.7 | 2.7 | 3.1 | 3.1 | 3.7 | 3.7 | 3.7 | 3.7 | 3.7 | 3.7 | 3.7 | 3.7 |

| Grade (%) | 0.5 | 4.5 | 2.0 | 6.5 | 3.0 | 7.5 | 4.0 | 8.5 | 4.0 | 8.0 | 5.5 | 10 | 7.0 | 12.5 | 8.5 | 14.5 |

| Stimulant medication exposure, n (%) | ||||||||||||||||

| No | 0 (0) | 6 (2.2) | 22 (8.2 | 38 (14.2) | 45 (16.9) | 139 (52.1) | 17 (6.4) | 0 (0) | ||||||||

| Yes | 1 (1.1) | 3 (3.4) | 4 (4.5) | 9 (10.1) | 20 (22.5) | 47 (52.8) | 5 (5.6) | 0 (0) | ||||||||

Stimulant medication users (assigned to exercise testing; n = 143) were more likely than all nonusers (assigned to exercise testing; n = 6309) to be excluded from the treadmill testing (odds ratio [OR] = 2.78, 95% CI 1.83 to 4.22, p < 0.0001). Among the explanatory categories for exclusion, stimulant users were more likely to be excluded because of “physical limitations” (OR = 2.59, 95% CI 1.04 to 6.48, p = 0.03), “cardiovascular conditions” (OR = 2.31, 95% CI 1.23 to 4.33, p = 0.007), and “other specific reasons” (OR = 3.28, 95% CI 1.57 to 6.85, p = 0.0008). No significant difference between stimulant users and all nonusers was observed for exclusion categories of “lung/breathing conditions,” “asthma,” and “medications.” Excluded stimulant users (n = 54) had a trend toward higher BMI than included stimulant users (n = 89; mean 22.5 kg/m2 [SD = 5.99] vs. 20.9 kg/m2 [SD = 4.88], t(141) = 1.73, p = 0.09). The same pattern was observed for excluded and included stimulant users when comparing the log of BMI (p = 0.10). The odds of the exercise testing being halted because of “priority 1” (OR = 2.23, 95% CI 0.69 to 7.20, p = 0.17) or “priority 2” (OR = 1.20, 95% CI 0.70 to 2.07, p = 0.50) stopping criteria did not significantly differ between stimulant users and all nonusers.

Exercise outcomes and stimulant exposure

The results of primary linear mixed model analyses, adjusting for the 12 covariates, revealed that the peak HR achieved during submaximal exercise testing (stage 2) was modestly lower in stimulant users compared to matched nonusers (raw p = 0.055, FDR-adjusted p = 0.137, Cohen's d = 0.422; Table 3). The HR at the end of 1-minute recovery was also lower in stimulant users compared to matched nonusers (raw p = 0.030, FDR-adjusted p = 0.137, Cohen's d = 0.482). However, the difference between Stage 2 HR and 1-minute recovery HR (i.e., submaximal HRR) was not different between stimulant users and matched nonusers (raw p = 0.38, FDR-adjusted p = 0.475, Cohen's d = 0.191). Stage 2 SBP and 1-minute recovery SBP also did not differ between stimulant users and matched nonusers (Table 3).

Table 3.

The Effect of Stimulant Medication Exposure on Stage 2 Heart Rate and Systolic Blood Pressure, First Minute Recovery Heart Rate, Systolic Blood Pressure, and Heart Rate Recovery During the Submaximal Treadmill Exercise Test in the Propensity Score-Matched Cohort While Adjusting for the 12 Covariates in the Model

| Stage 2 heart rate | Stage 2 SBP | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Parameter estimatea | LS mean estimate | SE | 95% CI | p | Parameter estimatea | LS mean estimate | SE | 95% CI | p |

| Stimulant use | 3.36 | 1.73 | (−0.079 to 6.80) | 0.055b | 2.32 | 2.42 | (−2.51 to 7.14) | 0.34c | ||

| Yes | 154.9 | 2.78 | (149.4 to 160.5) | 158.0 | 3.22 | (151.6 to 164.4) | ||||

| No | 158.3 | 2.24 | (153.8 to 162.8) | 160.3 | 3.09 | (154.2 to 166.5) | ||||

| First minute recovery heart rated | First minute recovery SBPd | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Parameter estimatea | LS mean estimate | SE | 95% CI | p | Parameter estimatea | LS mean estimate | SE | 95% CI | p |

| Stimulant use | 4.30 | 1.95 | (0.43 to 8.17) | 0.030e | −0.55 | 2.36 | (−5.24 to 4.14) | 0.82f | ||

| Yes | 142.2 | 2.76 | (136.7 to 147.7) | 150.1 | 3.05 | (144.0 to 156.1) | ||||

| No | 146.5 | 1.91 | (142.7 to 150.3) | 149.5 | 2.93 | (143.7 to 155.3) | ||||

| Submaximal HRR at first minuteg | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Parameter estimatea | LS mean estimate | SE | 95% CI | p |

| Stimulant use | −0.90 | 1.02 | (−2.93 to 1.14) | 0.38h | |

| Yes | 13.0 | 1.96 | (9.09 to 16.9) | ||

| No | 12.1 | 1.42 | (9.27 to 14.9) | ||

Difference of LS mean estimates.

FDR–adjusted p = 0.137; Cohen's d = 0.422.

FDR–adjusted p = 0.475; Cohen's d = 0.215.

Heart rate at the end of the first minute of exercise recovery.

FDR–adjusted p = 0.137; Cohen's d = 0.482.

FDR–adjusted p = 0.820; Cohen's d = 0.051.

Defined by subtracting the first-minute recovery HR from the stage 2 HR.

FDR–adjusted p = 0.475; Cohen's d = 0.191.

CI, confidence interval; FDR, false discovery rate; HR, heart rate; HRR, heart rate recovery; LS, least squares; SBP, systolic blood pressure; SE, standard error.

Secondary outcomes for warm-up, Stage 1, and 2-min/3-min recovery were examined in the linear mixed model analysis (with adjustment for the 12 covariates). The results showed that stimulant users versus matched nonusers had lower warm-up SBP (LS mean estimates of 127.7 [SE = 2.24] vs. 131.7 [SE = 1.95], raw p = 0.027, FDR-adjusted p = 0.027, Cohen's d = 0.479), lower 2-minute HR recovery (LS mean estimates of 120.6 [SE = 3.19] vs. 125.3 [SE = 2.43], raw p = 0.014, FDR-adjusted p = 0.027, Cohen's d = 0.549), and lower 2-minute recovery SBP (LS mean estimates of 140.8 [SE = 3.11] vs. 145.0 [SE = 2.74], raw p = 0.027, FDR-adjusted p = 0.027, Cohen's d = 0.495). Warm-up HR, Stage 1 HR and SBP, and 3-minute recovery HR and SBP did not significantly differ (i.e., p > 0.05, unadjusted for multiple testing) between stimulant users and matched nonusers.

Linear mixed models of each exercise outcome were repeated without adjusting for the 12 covariates in the model and showed the same pattern of results as those described above for the covariate-adjusted mixed model (results not shown).

Sensitivity analyses for exercise outcomes and stimulant exposure

The distribution of duration of stimulant use was weighted more toward chronic use than acute use. The mean duration of use was 1031 days (SD = 991) and the median duration was 730 days (interquartile range = 1217). Only nine stimulant users had initiated use within 90 days of being surveyed (Table 4). A large number of participants reported duration in multiples of 365 days (n = 12; 730 days, n = 12; 1095 days, n = 8; 1460 days, n = 11). Duration of stimulant use, when analyzed in the mixed model as a continuous measure or categorized in quartiles or quintiles, did not significantly impact any of the five primary outcomes (Stage 2 HR and SBP, 1-minute recovery HR and SBP, and submaximal HRR at 1-minute, raw p > 0.05).

Table 4.

Duration of Stimulant Medication Use (Intervals, Quartiles, and Quintiles) Reported by Stimulant Users (n = 89) Who Underwent Submaximal Exercise Testing

| Intervals | Quartiles | Quintiles | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Days | Stimulant users, n (%) | Days | Stimulant users, n (%) | Days | Stimulant users, n (%) |

| 1–30 | 7 (7.9) | 1–243 | 23 (25.8) | 1–182 | 22 (24.7) |

| 31–60 | 1 (1.1) | 183–365 | 14 (15.7) | ||

| 61–90 | 1 (1.1) | 244–730 | 28 (31.5) | 366–1095 | 23 (25.8) |

| 91–120 | 3 (3.4) | 731–1460 | 19 (21.3) | 1096–1825 | 17 (19.1) |

| 121–150 | 3 (3.4) | 1461+ | 19 (21.3) | 1826+ | 13 (14.6) |

| 151+ | 74 (83.1) | ||||

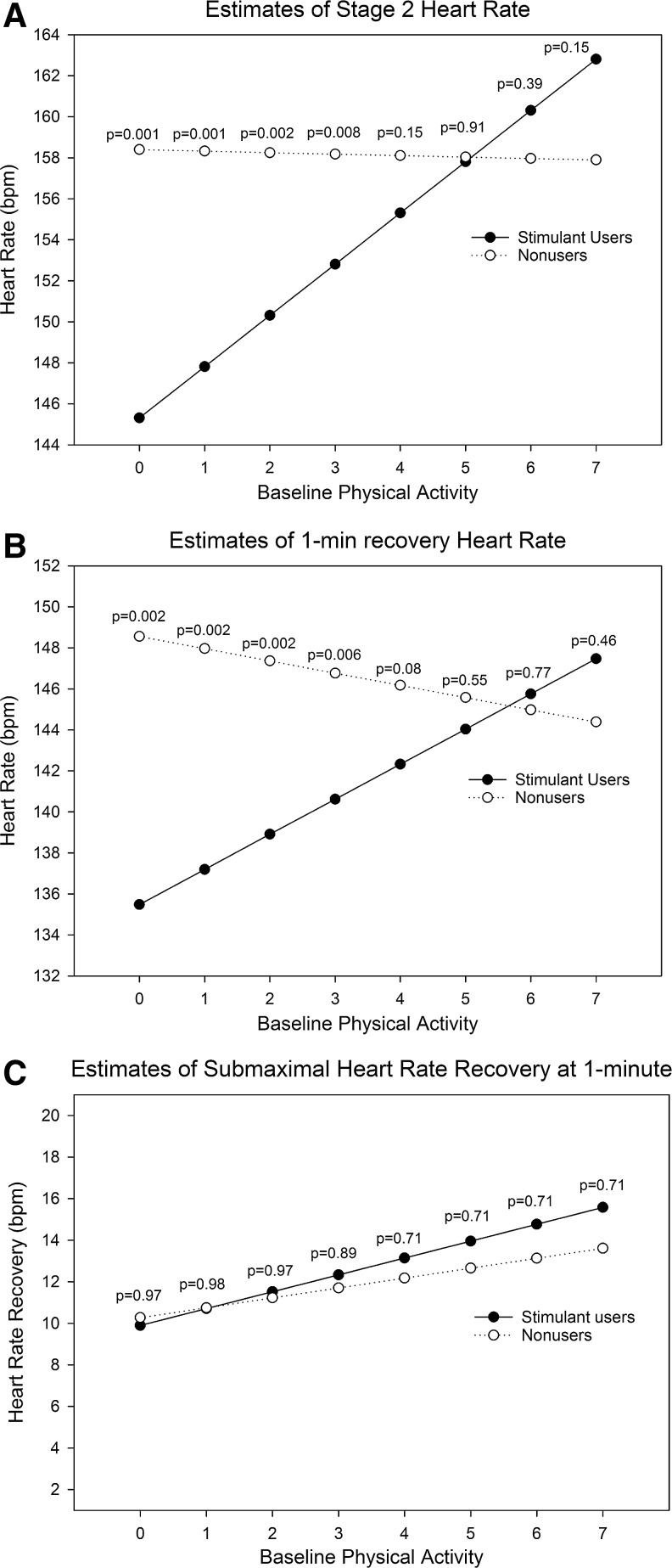

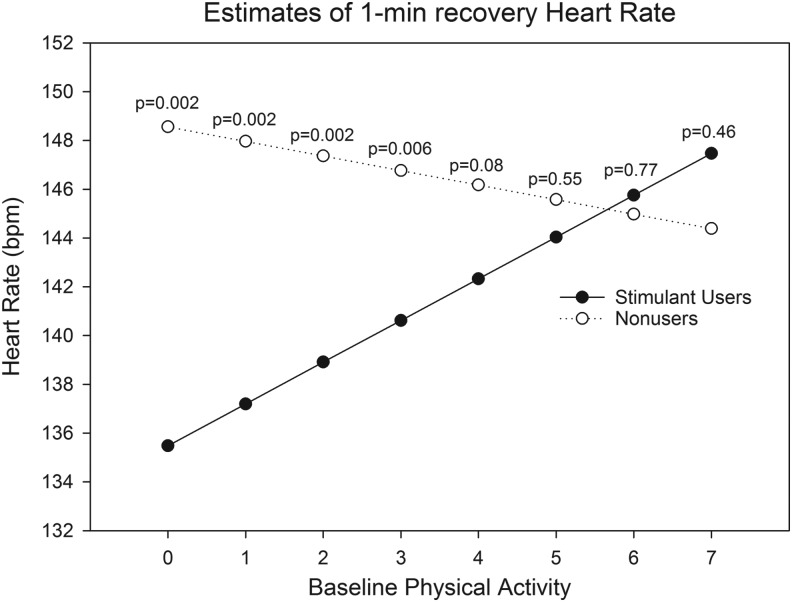

Baseline physical activity was a significant moderator of Stage 2 HR (p = 0.0014) and 1-minute recovery HR (p = 0.0045). Among participants with lower levels of self-reported physical activity, stimulant users had lower HR estimates in stage 2 (Fig. 2A) and 1-minute recovery (Fig. 2B) than matched nonusers. At higher levels of physical activity (i.e., levels 6 and 7), the HR estimates were higher for stimulant users than matched nonusers, although the differences were not statistically significant. Baseline physical activity was not a significant moderator of submaximal HRR (Fig. 2C; p = 0.47), although the difference between estimates for stimulant users and matched nonusers was greatest at higher levels of baseline physical activity. Because baseline physical activity was a determinant of the exercise protocol assigned, we assessed “exercise protocol used” as a moderator of submaximal HRR. The same basic pattern as that observed for baseline physical activity was also observed for exercise protocol used—estimates of submaximal HRR were higher in stimulant users compared to matched nonusers at the highest levels of exercise used, but overall exercise protocol difficulty was not a significant moderator (Fig. 3; p = 0.67). Gender and BMI were not significant moderators of the effect of stimulant medication exposure on any of the primary exercise outcomes (results not reported).

FIG. 2.

Estimates of (A) Stage 2 HR, (B) 1-minute recovery HR, and (C) 1-minute submaximal HR recovery at levels of baseline physical activity (0–7) in stimulant medication users and matched nonusers, adjusted for the other covariates. p-Values indicate the significance of the difference between estimates for users and matched nonusers at each level of baseline physical activity, adjusted for multiple testing (false discovery rate adjusted). HR, heart rate.

FIG. 3.

Estimates of 1-minute submaximal heart rate recovery at exercise protocols used (1–7; protocol 8 was not used) in stimulant medication users and matched nonusers, adjusted for the other covariates. p-Values indicate the significance of the difference between estimates for users and matched nonusers at each level of the exercise protocol used, adjusted for multiple testing (false discovery rate adjusted).

Discussion

Large scale fitness testing in the NHANES continuous survey from 1999 to 2004 allowed us to conduct the first study (to our knowledge) of the impact of stimulant medication use on HR and SBP during submaximal exercise testing in adolescents. Stimulant medication users had a lower HR estimate compared to matched nonusers at every time point during treadmill testing, except 3-minute recovery. During peak exercise (i.e., Stage 2)—the most important time point to assess HR—stimulant users' HR estimate was 3.4 bpm lower than matched nonusers'. While this difference was not statistically significant (FDR adjusted p < 0.05), the pattern of lower HR estimates in stimulant users compared to matched nonusers is suggestive of stimulant users having decreased chronotropic drive during submaximal exercise. Baseline physical activity was a significant moderator of stimulant medication use on Stage 2 HR and 1-minute recovery HR. Stimulant medical users with lower baseline physical activity were significantly more likely to have lower HR than equivalent nonusers. On the contrary, estimates of submaximal HRR at 1-minute recovery did not differ between stimulant users and matched nonusers. Duration of stimulant use exceeded 150 days for 83% of stimulant users, indicating mostly long-term chronic use. Correlating these results with the theory that stimulants may be associated with a “chronic systemic stress syndrome,” the observed decreased HR in stimulant users suggests downregulation of cardiac beta receptors, but the lack of delayed HRR does not suggest decreased parasympathetic activation during recovery.

Similarly, adult stimulant medication users compared to matched nonusers had significantly lower peak HR (175.5 vs. 179.4 bpm, p < 0.0001) during maximal exercise in our prior study (Westover et al. 2015). In contrast to the present study of adolescents, adult stimulant users had increased risk of delayed maximal HRR at 1 minute (a binary outcome present when difference between peak HR and 1-minute recovery HR ≤12 bpm) compared to matched nonusers (Westover et al. 2016). That SBP in adolescent stimulant users compared to matched nonusers was significantly decreased at 2-minute recovery, but almost identical at 1-minute recovery, contrasted with the finding of increased risk of delayed SBP recovery in adult users (Westover et al. 2016).

We had theorized that chronic use of stimulants, compared to acute use, would have a greater association with decreased stage 2 HR and a greater delay in 1-minute submaximal HRR due to chronic adaptation of the autonomic nervous system. What constitutes acute use and chronic use is not defined in the literature; thus, we categorized duration using three strategies (intervals, quartiles, and quintiles). However, duration of stimulant medication use did not impact any of the primary outcomes, no matter the categorization. Because there was so little short-term acute use, interpretation of this finding is limited. Inaccurate recall of duration of use by participants, assuming that participants equally underestimated and overestimated their use, would bias the results to the null.

The finding of baseline physical activity as a moderator of stimulant use on HR during Stage 2 and 1-minute recovery HR is novel. Less fit stimulant users had decreased HR in comparison to equally less fit matched nonusers during submaximal exercise testing. The interpretation of this is complicated by the fact that baseline physical activity was a determinant of the exercise protocol assigned to each participant. The purpose of differential protocol assignment was to have each participant reach 70%–80% of their HR maximum. Estimates of Stage 2 HR were essentially the same for all nonusers, no matter the baseline physical activity, as envisioned by study design. However, that was not the case for stimulant medication users (Fig. 2A). The lower HR observed with stimulant users reporting decreased baseline physical activity was likely due to either/both (1) decreased sympathetic activation or/and (2) decreased sensitivity to sympathetic activation. This finding should be tested in future studies.

Other studies have provided evidence of stimulant-associated chronotropic effects. Adult habitual cocaine smokers compared to age-matched controls who underwent symptom-limited cycle ergometry had a significantly lower maximum HR. Male and female cocaine users achieved 7% and 9% lower on percent predicted maximum HR achieved, respectively, compared to controls (Marques-Magallanes et al. 1997). Two prior small studies have shown evidence for delayed HRR in adult stimulant users. In one study, stimulant users with ADHD demonstrated a 7 bpm delay in 1-minute HRR compared to controls (p = 0.001) during a symptom-limited treadmill exercise stress test (Schubiner et al. 2006). In the other, stimulant users with ADHD had a 4 bpm delay in 1-minute HRR compared to controls (p = 0.05) during symptom-limited cycle ergometry (Hammerness et al. 2012).

A number of reasons may explain why submaximal HRR was not decreased in adolescent stimulant users compared to matched nonusers. One commonality between the three studies (Schubiner et al. 2006; Hammerness et al. 2012; Westover et al. 2016) that demonstrated delayed HRR (cited in the previous paragraph) was that they were maximal or symptom-limited exercise tests and not submaximal exercise tests. It may be that submaximal exercise does not elicit sufficient sympathetic activation such that differences in HRR between exposed and unexposed can be observed. Notably, the absolute difference between submaximal HRR at 1 minute in stimulant users and nonusers diverged as baseline physical activity increased (Fig. 2C) and the difficulty of the exercise protocol used increased (Fig. 3; baseline physical activity was a determinant of the exercise protocol assigned). Although these differences were not significant, had maximal exercise testing been performed the HRR estimates between stimulant users and nonusers might have further diverged.

Age-related differences in autonomic nervous system activity may also be explanatory. As age increases, cardiovascular activation of the sympathetic nervous system increases, while parasympathetic activation and HRV decrease (Pfeifer et al. 1983; Antelmi et al. 2004). In addition, if stimulant-associated chronotropic incompetence and delayed HRR in adults are conceived as exacerbating underlying cardiovascular disease, then it would be less likely to be observed in adolescents who have a much lower prevalence of cardiovascular disease. Moreover, adults on stimulants may potentially have much longer drug exposure compared to adolescents. On the contrary, these findings may be viewed as nonconfirmatory vis-à-vis the relationship between stimulant medication use and delayed HRR, although the lack of maximal exercise testing gives us pause in concluding this.

Stimulant medication users were more likely to be excluded from participation in the submaximal treadmill test than all nonusers. Among the subcategories of exclusions where stimulant users were more likely to be excluded, “physical limitations” include difficulties in walking or standing, “cardiovascular conditions” include history of myocardial infarction, stroke, chest pain during physical activity, resting HR ≥100 bpm, irregular heartbeats, and high resting BP (SBP ≥180 mmHg, diastolic blood pressure ≥100 mmHg), and “other specific reasons” include hospitalization in the past 3 months, doctor's recommendation against participation in sports, and “other safety concerns” by either the participant or study staff (National Center for Health Statistics 2009). Only subcategories of exclusion reasons were provided in the data, not the specific condition(s). Further research is needed to understand the appropriateness of adolescent stimulant users for exercise testing. Notably, the exercise outcomes analyzed in this study only apply to stimulant medication users well enough to undergo and complete submaximal exercise testing.

Strengths of this study include the use of a nationally representative data set (NHANES), where measurements of baseline characteristics were performed (e.g., tobacco/nicotine use, BMI, fitness level) and tight propensity-score matching was achieved. That perceived effort was measured during the submaximal exercise testing and was equivalent between stimulant users, and matched nonusers addressed the potential criticism that the exposure groups might differ on motivation and effort. That duration of stimulant medication was available and allowed us to test for acute versus chronic effects.

Limitations of the study include that stimulant dosing was not available. While a dose–response relationship is often considered evidence of causality, past evidence does not entirely point to this in the case of stimulants. For example, no dose–response relationship was observed between stimulant medications and decreased HRV in children and adolescents taking stimulant medications (Kelly et al. 2014). No dose–response was found between methylphenidate use and increased risk of sudden death and ventricular arrhythmia (Schelleman et al. 2012). An additional weakness is that prior stimulant medication use, medication adherence, and potential variation in the temporal relationship between stimulant use and exercise testing are unknown. The presence of these would bias the results to the null. Likewise, stimulant medication “drug holidays” could impact exposure status depending on their timing: (1) those reporting an ADHD diagnosis and not taking a stimulant medication in the past month would have been excluded from the cohort, (2) those not reporting ADHD and not taking stimulant medications in the past month due to drug holiday could have been included as a matched nonuser, and (3) those that took a stimulant medication in the past month but were on a drug holiday at the time of exercise testing would be classified as stimulant users. In the latter two cases, this would bias the results to the null due to the “mixing” of exposure status. Finally, the present study may have been underpowered. The previous study of adults had almost three times more stimulant users than the present study and, for example, a larger effect size for maximal HRR (d ∼ 0.41) than the present study's effect size for submaximal HRR (d ∼ 0.19).

Conclusions

Adolescent stimulant medication users compared to matched nonusers demonstrated a trend toward decreased HR during submaximal exercise, which is potential evidence of chronic adaptation with stimulant exposure. There was no evidence of delayed HRR in this study, and thus, no evidence for decreased parasympathetic activity during initial exercise recovery. This contrasts with our prior studies of adults, which showed robust evidence for increased odds of chronotropic incompetence and delayed HRR (Westover et al. 2015, 2016). A study utilizing a larger sample of adolescent stimulant users with matched controls undergoing maximal exercise testing could better assess whether adolescent stimulant users are at greater risk for chronotropic incompetence and delayed HRR. While links between chronotropic incompetence and HRR and mortality have been established in general adult populations (Lauer et al. 1996; Nishime et al. 2000; Huang et al. 2008; Brubaker and Kitzman 2011), no study has examined stimulant-associated chronotropic incompetence and HRR and mortality. Furthermore, the evidence for a link between stimulant medication use and serious cardiovascular events is less in children and adolescents (Cooper et al. 2011; Schelleman et al. 2011; Dalsgaard et al. 2014) than in adults (Habel et al. 2011; Schelleman et al. 2012). This exercise study of adolescents and the prior exercise studies of adults (Westover et al. 2015, 2016) suggest that maximal exercise testing may have utility in research as an intermediate outcome to assess stimulant-associated autonomic nervous system adaptations. However, the evidence to date does not support clinical use of exercise testing in stimulant users. Furthermore, this study suggests that stimulant-associated autonomic adaptation, if present, may be less likely to be observed in adolescent stimulant users compared to adult users.

Clinical Significance

It is theorized that chronic use of stimulant medications can cause adaptation of the autonomic nervous system, which may be evidenced in maximal exercise testing as inappropriately low HR during peak exercise and delayed HRR during the recovery period after exercise. In this study of adolescents undergoing submaximal treadmill exercise testing, stimulant users trended toward decreased HR during exercise, but did not display delayed HRR after exercise compared to nonusers. These results suggest potential autonomic nervous system adaptation, but conclusions are tempered by the lack of maximal exercise testing. At this time, there is no clinical utility in exercise testing in adolescent stimulant users, but maximal exercise testing outcomes may be used as useful intermediate outcomes in future studies assessing the impact of chronic stimulant use.

Acknowledgments

A.N.W. is a consultant for Intra-Cellular Therapies on a research study. S.B. has received research grants from Forest Laboratories and Sunovion. None of these grants or relationships involves stimulant medications.

Disclosures

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- Algra A, Tijssen JG, Roelandt JR, Pool J, Lubsen J: Heart rate variability from 24-hour electrocardiography and the 2-year risk for sudden death. Circulation 88:180–185, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antelmi I, De Paula RS, Shinzato AR, Peres CA, Mansur AJ, Grupi CJ: Influence of age, gender, body mass index, and functional capacity on heart rate variability in a cohort of subjects without heart disease. Am J Cardiol 93:381–385, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bejerot S, Ryden EM, Arlinde CM: Two-year outcome of treatment with central stimulant medication in adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A prospective study. J Clin Psychiatry 71:1590–1597, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergstralh E, Kosanke J: Locally written SAS macros (gmatch). 2003. Available at www.mayo.edu/research/departments-divisions/department-health-sciences-research/division-biomedical-statistics-informatics/software/locally-written-sas-macros (Accessed May19, 2016)

- Brubaker PH, Kitzman DW: Chronotropic incompetence: Causes, consequences, and management. Circulation 123:1010–1020, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics: BMI-for-age charts, 2 to 20 years, selected BMI (kilograms/meters squared) z-scores, by sex and age. 2009. Available at www.cdc.gov/growthcharts/zscore.htm (Accessed May19, 2016)

- Cooper WO, Habel LA, Sox CM, Chan KA, Arbogast PG, Cheetham TC, Murray KT, Quinn VP, Stein CM, Callahan ST, Fireman BH, Fish FA, Kirshner HS, O'Duffy A, Connell FA, Ray WA: ADHD drugs and serious cardiovascular events in children and young adults. N Eng J Med 365:1896–1904, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalsgaard S, Kvist AP, Leckman JF, Nielsen HS, Simonsen M: Cardiovascular safety of stimulants in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A nationwide prospective cohort study. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 24:302–310, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Express Scripts: Turning attention to ADHD: U.S. medication trends for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. 2014. Available at http://lab.express-scripts.com/insights/industry-updates/∼/media/89fb0aba100743b5956ad0b5ab286110.ashx (Accessed May19, 2016)

- Habel LA, Cooper WO, Sox CM, Chan KA, Fireman BH, Arbogast PG, Cheetham TC, Quinn VP, Dublin S, Boudreau DM, Andrade SE, Pawloski PA, Raebel MA, Smith DH, Achacoso N, Uratsu C, Go AS, Sidney S, Nguyen-Huynh MN, Ray WA, Selby JV: ADHD medications and risk of serious cardiovascular events in young and middle-aged adults. JAMA 306:2673–2683, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammerness P, Zusman R, Systrom D, Surman C, Baggish A, Schillinger M, Shelley-Abrahamson R, Wilens TE: A cardiopulmonary study of lisdexamfetamine in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. World J Biol Psychiatry 14:299–306, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang CL, Su TC, Chen WJ, Lin LY, Wang WL, Feng MH, Liau CS, Lee YT, Chen MF: Usefulness of paradoxical systolic blood pressure increase after exercise as a predictor of cardiovascular mortality. Am J Cardiol 102:518–523, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly AS, Rudser KD, Dengel DR, Kaufman CL, Reiff MI, Norris AL, Metzig AM, Steinberger J: Cardiac autonomic dysfunction and arterial stiffness among children and adolescents with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder treated with stimulants. J Pediatr 165:755–759, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauer MS, Okin PM, Larson MG, Evans JC, Levy D: Impaired heart rate response to graded exercise: Prognostic implications of chronotropic incompetence in the framingham heart study. Circulation 93:1520–1526, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marques-Magallanes JA, Koyal SN, Cooper CB, Kleerup EC, Tashkin DP: Impact of habitual cocaine smoking on the physiologic response to maximum exercise. Chest 112:1008–1016, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mick E, McManus DD, Goldberg RJ: Meta-analysis of increased heart rate and blood pressure associated with CNS stimulant treatment of ADHD in adults. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 23:534–541, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Health Statistics: Cardiovascular Fitness Procedures Manual. 2004. Available at www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhanes/nhanes_03_04/cv_99-04.pdf (Accessed May19, 2016)

- National Center for Health Statistics: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey: 2003–2004 data documentation, codebook, and frequencies, cardiovascular fitness (CVX_C). 2009. Available at https://wwwn.cdc.gov/Nchs/Nhanes/2003-2004/CVX_C.htm#Appendix_A:_Exclusion_Criteria_Classification_for_the_NAHNES_Cardiovascular_Fitness_Component (Accessed May19, 2016)

- Nishime EO, Cole CR, Blackstone EH, Pashkow FJ, Lauer MS: Heart rate recovery and treadmill exercise score as predictors of mortality in patients referred for exercise ECG. JAMA 284:1392–1398, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olfson M, Blanco C, Wang S, Laje G, Correll CU: National trends in the mental health care of children, adolescents, and adults by office-based physicians. JAMA Psychiatry 71:81–90, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeifer MA, Weinberg CR, Cook D, Best JD, Reenan A, Halter JB. Differential changes of autonomic nervous system function with age in man. Am J Med 75:249–258, 1983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierpont GL, Adabag S, Yannopoulos D: Pathophysiology of exercise heart rate recovery: A comprehensive analysis. Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol 18:107–117, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB: The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika 70:41–55, 1983 [Google Scholar]

- Samuels JA, Franco K, Wan F, Sorof JM: Effect of stimulants on 24-h ambulatory blood pressure in children with ADHD: A double-blind, randomized, cross-over trial. Pediatr Nephrol 21:92–95, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schelleman H, Bilker WB, Kimmel SE, Daniel GW, Newcomb C, Guevara JP, Cziraky MJ, Strom BL, Hennessy S: Methylphenidate and risk of serious cardiovascular events in adults. Am J Psychiatry 169:178–185, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schelleman H, Bilker WB, Strom BL, Kimmel SE, Newcomb C, Guevara JP, Daniel GW, Cziraky MJ, Hennessy S: Cardiovascular events and death in children exposed and unexposed to ADHD agents. Pediatrics 127:1102–1110, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schubiner H, Hassunizadeh B, Kaczynski R: A controlled study of autonomic nervous system function in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder treated with stimulant medications: Results of a pilot study. J Atten Disord 10:205–211, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stowe CD, Gardner SF, Gist CC, Schulz EG, Wells TG: 24-Hour ambulatory blood pressure monitoring in male children receiving stimulant therapy. Ann Pharmacother 36:1142–1149, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitiello B, Elliott GR, Swanson JM, Arnold LE, Hechtman L, Abikoff H, Molina BS, Wells K, Wigal T, Jensen PS, Greenhill LL, Kaltman JR, Severe JB, Odbert C, Hur K, Gibbons R: Blood pressure and heart rate over 10 years in the multimodal treatment study of children with ADHD. Am J Psychiatry 169:167–177, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westover AN, Nakonezny PA, Barlow CE, Adinoff B, Brown ES, Halm EA, Vongpatanasin W, DeFina LF: Heart rate recovery and systolic blood pressure recovery after maximal exercise in prevalent users of stimulant medications. J Clin Psychopharmacol 36:295–297, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westover AN, Nakonezny PA, Barlow CE, Vongpatanasin W, Adinoff B, Brown ES, Mortensen EM, Halm EA, DeFina LF: Exercise outcomes in prevalent users of stimulant medications. J Psychiatr Res 64:32–39, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]