Abstract

Competency-based medical education (CBME) is gaining momentum across the globe. The Medical Council of India has described the basic competencies required of an Indian Medical Graduate and designed a competency-based module on attitudes and communication. Widespread adoption of a competency-based approach would mean a paradigm shift in the current approach to medical education. CBME, hence, needs to be reviewed for its usefulness and limitations in the Indian context. This article describes the rationale of CBME and provides an overview of its components, i.e., competency, entrustable professional activity, and milestones. It elaborates how CBME could be implemented in an institute, in the context of basic sciences in general and pharmacology in particular. The promises and perils of CBME that need to be kept in mind to maximize its gains are described.

Key words: Assessment, competency, entrustable professional activity, medical education

Competency-based Medical Education and its Rationale

The aim of imparting medical education is to train graduates to efficiently take care of the health needs of the society. The current medical education system is based on a curriculum that is subject-centered and time-based. Most evaluations are summative, with little opportunity for feedback. The teaching–learning activities and the assessment methods focus more on knowledge than on attitude and skills. Thus, graduates may have extraordinary knowledge, but may lack the basic clinical skills required in practice. In addition, they may also lack the soft skills related to communication, doctor–patient relationship, ethics, and professionalism.

Competency-based medical education (CBME) has been suggested and tried to tackle these concerns. Competency is defined as “the ability to do something successfully and efficiently,”[1] and CBME is an approach to ensure that the graduates develop the competencies required to fulfill the patients’ needs in the society. It de-emphasizes time-based training and promises greater accountability, flexibility, and learner-centeredness.[2] This means that teaching–learning and assessment would focus on the development of competencies and would continue till the desired competency is achieved. The training would continue not for a fixed duration, but till the time the standard of desired competency is attained. Assessments would be frequent and formative in nature, and feedback would be inbuilt in the process of training. Furthermore, each student would be assessed by a measurable standard which is objective and independent of the performance of other students. Thus, it is an approach in which the focus of teaching–learning and assessment is on real-life medical practice.

The Components of Competency-based Medical Education: Competency, Entrustable Professional Activity, and Milestones

Competency

Competency is the ability of a health professional which can be observed. It encompasses various components such as knowledge, skills, values, and attitudes. Competency is the application of competencies in an actual setting, and an individual who is able to do so is considered competent. The core competencies required of a medical graduate are predetermined in the curriculum and are contextual to the environment in which the medical graduate would eventually practice his profession. For example, six domains of general competency, namely, patient care, medical knowledge, practice-based learning and improvement, interpersonal and communication skills, professionalism, and systems-based practice have been described by the Accreditation Council of Graduate Medical Education in the USA.[3] Three broad outcomes have been specified for medical graduates in the UK, namely, doctor as a scholar and a scientist, doctor as a practitioner, and doctor as a researcher.[4] The Canadian Medical Education Directions for Specialists specifies seven roles of a specialist, namely, medical expert, communicator, collaborator, manager, health advocate, scholar, and professional.[5]

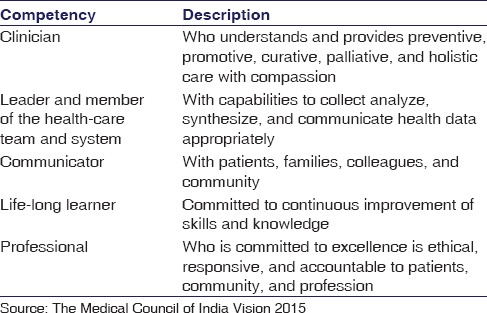

The Medical Council of India (MCI) has also suggested that competency-based learning must be implemented in all the medical colleges. It would include designing and implementing a curriculum that would focus on the desired and observable ability in real life situations. The competencies expected of an Indian Medical Graduate (IMG) are listed in Table 1.[6]

Table 1.

Competencies expected of an Indian Medical Graduate

Entrustable Professional Activity

Entrustable professional activity (EPA) helps bridge the gap between the theory and practice of CBME. While competencies are the abilities of a physician, EPAs are descriptors of work that define a profession. The process and outcomes of EPAs are observable and measurable. They require multiple competencies in an integrative, holistic nature.[7,8] For example, let us consider “management of tuberculosis (TB) at the primary level” as the EPA. It would require a definite set of knowledge (the clinical presentation of TB, the investigations needed, and the treatment protocol), skill (clinical interviewing, general and systemic examination pertaining to TB, and interpretation of the reports), and attitude (communicating with empathy, inviting questions, and offering appropriate guidance and advice). The core competencies reflected here would be those of a clinician, a communicator, and a professional.

Milestones

A competency is achieved gradually, step–by-step. These steps are designated as milestones. The Dreyfus model as applied to education would have five such steps or milestones. These are a novice, advanced beginner, competent, proficient, and expert.[9] From the supervisor’s perspective, these levels would progress to five levels. At the first level, the student only observes the EPA. At Levels 2 and 3, the student performs the EPA with direct, proactive supervision and with indirect supervision, respectively. At Level 4, the student is ready for independent, unsupervised practice and is given the “statement of awarded responsibility.” The fifth level is when the student is ready to assist other learners in performing the EPA.[8]

CBME thus encompasses the core competencies or the attributes required of a graduate to excel in his/her profession, the EPAs that together constitute the work role of the graduate in his/her practice, and a logical trajectory of professional development in the form of milestones. A detailed explanation of an EPA activity training and evaluation of a resident in pediatrics, taking an example of managing a child presenting with diarrhea has been described by Dhaliwal et al.[10]

Teaching–learning Methods in Competency-based Medical Education

Since CBME is learner-centered, offers flexibility in time, and focuses on all the three domains of learning together; the teaching–learning activities would need a change in structure and process. Since it focuses on outcomes and prepares students for actual professional practice, teaching–learning activities would be more skill-based, involving more clinical, hands-on experience. The students just entering medical profession would also get to see cases/patients and would have a stethoscope right in the beginning of their course, which would enhance their motivation for learning medicine.

Some examples of teaching methods adopted in CBME by a couple of African medical colleges include problem-based learning in the preclinical years and case-based learning in the clinical years, clinical pathological conferences, clinical audits, and early clinical exposure. Skills’ training was imparted in the laboratory and via practical sessions. Community-based research and service were also included. Information communication technology was additionally used to enhance learning.[11] For significant learning to happen by a competency-based curricular design, novel instructional methods such as a “flipped classroom” approach and “team-based learning” have also been suggested.[12]

One of the competencies expected of an IMG by the MCI is “being a life-long learner.” Hence, students must be provided ample opportunities for self-directed learning. The inbuilt feedback process would help them be aware of their own lacunae in learning. The teacher’s role would be to facilitate the student’s progress. This process of shaping the teaching–learning activities to meet a learning need would also assist lifelong learning.[13]

Assessment in Competency-based Medical Education

As CBME promises greater accountability, the assessment needs to be robust and multifaceted. The conclusions drawn from the formative assessments in CBME would be important for the trainee. The international collaborators for CBME have enlisted six key features of effective assessment in CBME.[14] First, it needs to be continuous and frequent. This is so that more formative assessments can take place to guide the student’s progress. Second, it must be criterion-based, using a developmental perspective. Thus, a student would not be deemed competent, merely because he is better than the rest, but only if and only when his performance matches a certain minimum required a standard of care. Third, the assessment needs to be largely work-based. Although simulation can be used in the early phases for assessment and feedback, direct observation, and assessment of authentic clinical encounters would be an essential component of CBME. Fourth, the assessment tools themselves must meet certain minimum standards of quality in terms of validity, reliability, accept ability, educational impact, and cost-effectiveness. Fifth, more qualitative approach to assessment must be incorporated. Judgments and feedback from experts are more meaningful than numbers, scores, or grades. Moreover, sixth, assessment should draw upon the wisdom of a group, and the trainee should himself be actively involved in the assessment process. This means that a greater use needs to be made of multiple tools of assessment including work-place-based assessment tools such as mini-clinical evaluation exercise, direct observation, multisource feedback, and records of clinical work such as logbooks and portfolios.

Formative assessments with feedback, largely work-based, would form the backbone of CBME. To shape the development of the student in the right direction, frequent assessments with qualitative feedback from teachers would be required. Assessment may not always be objective, and we should be prepared for subjective assessment by experts. These have been found to be reliable and provide more meaning and direction to the learner than numeric scores. In other words, we would be required to give up the insistence for objectivity in assessment, as it is the subjective judgments and feedback by experts which will have a high educational impact, crucial for the success of CBME.

How to Implement Competency-based Medical Education in the Institute

Implementation of CBME would begin with sensitization and training of the faculty and the curriculum planners. The subject experts would need to get together and identify the EPAs pertaining to the health needs in their respective specialty, and the core competencies involved. In addition to designing the fine aspects of the curriculum, care must be taken to avoid duplication and inadvertent deletion of core competencies, and to ensure synchronization so that students are trained to develop the relevant competencies at the right time. The milestones to be achieved at the end of each year need to be decided. Ongoing feedback and continuous revision and modification would be necessary.

Broadly, three steps of competency-based curriculum planning and strategies for implementation in the Indian context have been described, namely, identification of competencies, content identification and program organization, and assessment planning and program evaluation.[15] Curriculum map as a tool can be used to ensure that the competencies, the teaching–learning methods, and assessment methods are constructively aligned.[16]

Challenges in the Implementation of Competency-based Medical Education

Considering the fact that CBME is a relatively novel concept in India, sensitization and training of stakeholders and faculty would be necessary to enhance acceptance and also ensure uniform implementation of the CBME-based curriculum across all medical schools in the country. Comprehending what competency exactly refers to, how it differs from EPA, where would the milestones fit in, how to integrate “Knowledge, skill, attitude” components therein, and what are “competency domains” as opposed to competencies, may be perceived as a challenging task. Bringing about a paradigm shift in our teaching–learning and assessment methods would be a difficult process. Finally, working out the logistics of implementation which includes procuring additional resources in terms of infrastructure, material, and workforce would be necessary. CBME de-emphasizes time-based training, but to manage a cohort of learners, wherein each one progresses at a different pace may be a challenge. To evaluate whether we actually achieve what CBME promises to offer, i.e., competent graduates, is yet another challenge. The impact of CBME in achieving this long-term goal can only be evaluated in real terms when the IMG begins to practice his/her clinical competencies independently in real life situations. These challenges explain the reluctance and apprehension among teachers, learners, and educational administrators about CBME.[17]

Developing a Competency-based Curriculum for Pharmacology

The curriculum in pharmacology is witnessing a sea change from emphasis on animal experiments and dispensing pharmacy-based curriculum, to an “applied” approach, where the emphasis is on how the student prescribes rationally, taking into view the various facets of the medicine and the patient. Traditional pharmacology teaching has been criticized for not preparing students for medical practice, nor teaching the safe and rational use of medicines. The mention of these in the textbooks is perfunctory. The need for a change to a competency-based curriculum has been felt worldwide. For example, a new curriculum that was planned for the medical school at Lund University, Sweden, identified pharmacology as a subject that needs to be strengthened based on needs in the health-care system. A modified three-round Delphi technique was used where 31 physicians were invited to list and classify necessary competencies for a new curriculum in basic and clinical pharmacology. A total of 40 competencies were identified that could be transferred to learning outcomes for the new curriculum.[18] In India too, various medical schools have been attempting to redefine the teaching–learning methodologies. A radical shift was witnessed in this decade. However, the change has been cosmetic, the approach remaining conventional, rather than practice, skill, and competency based. Let us consider a common example of administering injectable drugs by students. As of now, they are taught theoretically, and at some places, they are being taught with mannequins. However, when the students enter the final year, and later during internship, they are told to relearn it with a comment that whatever they learned earlier was not appropriate, or in a way, they are not considered competent. It means that we need to develop this competency up to an acceptable level during the 2nd year itself, and hence we need to revisit our teaching and assessment methodology, in the context of CBME.

Listed below are some competencies that are suggested for an undergraduate student in pharmacology:

Be able to identify the commonly used drug formulations, understand their advantages and disadvantages, to select them appropriately for a given condition

Be familiar with the national essential medicines list, the criteria on which the list was developed, their advantages and appropriate use in practice

Be able to select personal or P-drugs for common diseases and write a correct prescription for a given patient

Be aware of the pros and cons of pharmaceutical promotion and be able to respond effectively to them

Be aware of commercial and noncommercial sources of drug information and use them to update themselves and to prescribe medicines

Be able to understand the implications of misuse of medicines in general and antimicrobials in particular

Be able to analyze prescriptions using the WHO prescribing indicators and be able to use the same as a guide of their own prescribing behavior

Be able to communicate appropriate drug and nondrug information about common diseases to a patient with the aim to ensure compliance with drug therapy

Be able to detect, monitor, and report adverse drug reactions

Be able to appreciate the need to calculate doses of drugs and determine accurate drug doses wherever applicable

Be able to counsel patients regarding correct methods of drug administration using special devices, and also the correct methods of storing and disposal of medicines.

While these and other skills have been defined in the current curriculum, there is a need to alter the teaching, learning, and assessment methods to reshape these into a competency-based curriculum. It means redefining the learning objectives, adoption of teaching methods that emphasize skills development, and objective methods of evaluation with inbuilt feedback. It also means that the training does not stop at the end of the second professional year, but progresses seamlessly into the remaining years, until the student graduates, and until the defined level of competency is achieved.

Weighing the Pros and Cons of Competency-based Medical Education

The strength of CBME is that it focuses on outcomes. Furthermore, it accepts that each learner is unique and learns at his/her own pace. There seems to be a better scope of teaching the “art” of medicine that includes attitudinal and communication skills and values related to ethics and professionalism. It promises greater accountability because the assessments are very close to what would actually be done in real life situations.

However, CBME should not be considered as a panacea for all the problems related to medical education. It should not end up being a yet another change in the curriculum that does not actually address the problems of the conventional curriculum. Brightwell and Grant opine that CBME is inadequate to describe the higher order skills necessary for professional practice and suggest that more emphasis should be put on learning in the workplace, in the existing curriculum itself, rather than an uncritical adoption of CBME.[19] Frank et al. in their article “Competence-based medical education: Theory to practice”[20] have also described the possible perils of CBME such as, in an attempt to define competencies and subcompetencies, we may come up with a long list of abilities, and the essence of the subject may be lost. The students, who are used to teacher-driven and time-based learning, may find it difficult to cope with CBME. In their pursuit of achieving predefined milestones, there is a risk that learners may stop thriving for excellence. The de-emphasis on time-based training may create a chaotic situation wherein learners progress at their own pace. A lot of additional resources including workforce and material would be required to implement CBME. The teachers would also face the challenge of altering their attitude and approach to meet the purpose of CBME.[20]

Moreover, the essence of professional practice is in its uniqueness. Each patient has unique medical and psychosocial needs, which the doctor must be sensitive to. The doctor must be able to link theory to practice in his/her own mind, and using his/her analytical and problem-solving skill must be able to do what is best for that particular patient. Moreover, whether this unique best, decided by the doctor for that unique patient, can be best learned by a CBME approach or by a more effective implementation of the conventional curriculum, is a question that is yet to be answered.

The Future of Competency-based Medical Education

The MCI has been intent in gently moving toward a competency-based curriculum as described in its Vision 2015 document.[21] However, to maximize the gains of CBME, a hybrid approach has been suggested wherein CBME should be inbuilt in the tenets of the conventional curriculum in the initial phases of the change, and then the conventional curriculum could be gradually replaced by CBME. This would ensure that the stakeholders would not be overwhelmed by a sudden change, while also providing an opportunity to measure and analyze the benefits of CBME.

The way we design and implement CBME would matter a lot for its success. If the principles of CBME are implemented as per the regional context and circumstances, we may reap the fruits. Initial employment of a hybrid curriculum-part traditional and part CBME - would make the transition more acceptable.

Financial Support and Sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Soanes C, Stevenson A, editors. The Oxford Dictionary of English. Revised Edition. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Frank JR, Mungroo R, Ahmad Y, Wang M, De Rossi S, Horsley T. Toward a definition of competency-based education in medicine: A systematic review of published definitions. Med Teach. 2010;32:631–7. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2010.500898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Swing SR. The ACGME outcome project: Retrospective and prospective. Med Teach. 2007;29:648–54. doi: 10.1080/01421590701392903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.General Medical Council. Tomorrow’s Doctors: Education Outcomes and Standards for Undergraduate Medical Education. [Last accessed on 2016 May 16]. Available from: http://www.gmc-uk.org/Tomorrow_s_Doctors_1214.pdf_48905759.pdf .

- 5.Frank JR, Danoff D. The CanMEDS initiative: Implementing an outcomes-based framework of physician competencies. Med Teach. 2007;29:642–7. doi: 10.1080/01421590701746983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Medical Council of India Regulations on Graduate Medical Education. 1997. [Last accessed on 2016 May 16]. Available from: http://www.mciindia.org/Rules-and-Regulation/GME_REGULATIONS.pdf .

- 7.Ten Cate O. Nuts and bolts of entrustable professional activities. J Grad Med Educ. 2013;5:157–8. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-12-00380.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.ten Cate O, Scheele F. Competency-based postgraduate training: Can we bridge the gap between theory and clinical practice? Acad Med. 2007;82:542–7. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31805559c7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Batalden P, Leach D, Swing S, Dreyfus H, Dreyfus S. General competencies and accreditation in graduate medical education. Health Aff (Millwood) 2002;21:103–11. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.21.5.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dhaliwal U, Gupta P, Singh T. Entrustable professional activities: Teaching and assessing clinical competence. Indian Pediatr. 2015;52:591–7. doi: 10.1007/s13312-015-0681-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kiguli-Malwadde E, Olapade-Olaopa EO, Kiguli S, Chen C, Sewankambo NK, Ogunniyi AO, et al. Competency-based medical education in two Sub-Saharan African medical schools. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2014;5:483–9. doi: 10.2147/AMEP.S68480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hurtubise L, Roman B. Competency-based curricular design to encourage significant learning. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2014;44:164–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cppeds.2014.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harris P, Snell L, Talbot M, Harden RM. Competency-based medical education: Implications for undergraduate programs. Med Teach. 2010;32:646–50. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2010.500703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holmboe ES, Sherbino J, Long DM, Swing SR, Frank JR. The role of assessment in competency-based medical education. Med Teach. 2010;32:676–82. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2010.500704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Modi JN, Gupta P, Singh T. Competency-based medical education, entrustment and assessment. Indian Pediatr. 2015;52:413–20. doi: 10.1007/s13312-015-0647-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Essary AC, Statler PM. Using a curriculum map to link the competencies for the PA profession with assessment tools in PA education. J Physician Assist Educ. 2007;18:22–8. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Snell LS, Frank JR. Competencies, the tea bag model, and the end of time. Med Teach. 2010;32:629–30. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2010.500707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Midlöv P, Höglund P, Eriksson T, Diehl A, Edgren G. Developing a competency-based curriculum in basic and clinical pharmacology – A Delphi study among physicians. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2015;117:413–20. doi: 10.1111/bcpt.12436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brightwell A, Grant J. Competency-based training: Who benefits? Postgrad Med J. 2013;89:107–10. doi: 10.1136/postgradmedj-2012-130881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frank JR, Snell LS, Cate OT, Holmboe ES, Carraccio C, Swing SR, et al. Competency-based medical education: Theory to practice. Med Teach. 2010;32:638–45. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2010.501190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vision 2015. New Delhi: Medical Council of India; 2011. [Last accessed on 2016 May 16]. Medical Council of India. Available from: http://www.mciindia.org/tools/announcement/MCI_booklet.pdf . [Google Scholar]