Abstract

Objectives:

Underreporting and poor quality of adverse drug reaction (ADR) reports pose a challenge for the Pharmacovigilance Program of India. A module to impart knowledge and skills of ADR reporting to MBBS students was developed and evaluated.

Materials and Methods:

The module consisted of (a) e-mailing an ADR narrative and online filling of the “suspected ADR reporting form” (SARF) and (b) a week later, practical on ADR reporting was conducted followed by online filling of SARF postpractical at 1 and 6 months. SARF was an 18-item form with a total score of 36. The module was implemented in the year 2012–2013. Feedback from students and faculty was taken using 15-item prevalidated feedback questionnaires. The module was modified based on the feedback and implemented for the subsequent batch in the year 2013–2014. The evaluation consisted of recording the number of students responding and the scores achieved.

Results:

A total of 171 students in 2012–2013 batch and 179 in 2013–2014 batch participated. In the 2012–2013 batch, the number of students filling the SARF decreased from basal: 171; 1 month: 122; 6 months: 17. The average scores showed improvement from basal 16.2 (45%) to 26.4 (73%) at 1 month and to 27.3 (76%) at 6 months. For the 2013–2014 batch, the number (n = 179) remained constant throughout and the average score progressively increased from basal 10.5 (30%) to 27.8 (77%) at 1 month and 30.3 (84%) at 6 months.

Conclusion:

This module improved the accuracy of filling SARF by students and this subsequently will led to better ADR reporting. Hence, this module can be used to inculcate better ADR reporting practices in budding physicians.

Key words: Adverse drug reaction reporting, feedback, pharmacovigilance, teaching module, undergraduate medical education

Key message: Use of an e-module for training students in ADR reporting skills was effective. The performance of students in filling ADR forms accurately increased, with a lesser number of students making mistakes. The module can be used to inculcate competency in ADR reporting in future health care professionals.

It is the moral responsibility and social accountability of every health-care professional to voluntarily report all adverse drug reactions (ADRs), new and unpredictable effects as well as predictable effects of marketed drugs. The reporting doctor has to capture the detailed background and description of the adverse event (AE) which is to be reported to the concerned drug authority in that country. The spontaneous ADR reporting for marketed drugs in India is covered under the Pharmacovigilance Program of India (PvPI)[1] which was initiated by the Central Drugs Standard Control Organisation, New Delhi, under the aegis of the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India in July 2010. The mission of PvPI is to safeguard the health of the Indian population by ensuring that the benefit of the use of medicine outweighs the risks associated with its use. The program aims to foster the culture of adverse drug event notification and generate broad-based ADR data on the Indian population and share the information with the global health-care community. The medical colleges who provide voluntary intent are inducted as ADR monitoring centers. As per this program, health-care professionals are requested to fill the suspected ADR reporting form (SARF) and submit to ADR monitoring centers.

In spite of the implementation of this program nationwide through medical colleges, the reporting of ADRs is far from satisfactory. The published literature shows that the underreporting is mainly due to ignorance on the part of clinicians, lack of time, and unawareness about their role in the program. The quality of reporting is also low.[2,3] In a questionnaire-based survey conducted by Rishi et al., wherein the medical practitioners cited the causes of underreporting of ADR as busy schedule (22%), do not know whom to report (14%), reporting could show ignorance (5%), negligence, apathy, general casualness (12%) toward ADR reporting, and do not want to take responsibility for fear of legal action.[4] Similar, studies concluded that ADR reporting by doctors was low despite having good knowledge of ADR.[5,6] Knowledge of first-year doctors regarding ADR reporting had also been reported to be quite poor.[7]

One of the approaches to improve this scenario is to target the budding doctors, i.e., the undergraduate students. Reporting of ADR to the concerned authority is a skill which must be developed and reinforced in MBBS students to be a competent and responsible health-care professional. ADR is being taught extensively in pharmacology curriculum to students through lectures, practicals, and tutorials. The training does not impart skills for detection of ADRs, critical evaluation of the cause, and monitoring. The assessment is also theory-driven and does not assess their familiarity with practical aspects of ADR reporting and causality. Hence, reforms in existing curriculum are essential to familiarize undergraduates with the current pharmacovigilance program and develop them into effective health-care professional ensuring patient safety in the long run. Hence, this study was planned to implement ADR reporting skill e-modules for MBBS students.

Materials and Methods

The study design was a prospective, single-group study. The project was initiated after permission from the Institutional Ethics Review Board. The second professional MBBS students entering the third semester in August 2012 in the institute were enrolled for participation in the study. Out of the total 180 students, who provided voluntary written consent, were included in the study.

Development of Adverse Drug Reaction Reporting Training e-module

The investigators of the project prepared AE case narrative for 6–8 different ADRs. The AE narrative included the patient details, description of the symptoms of ADR, investigations done, specific and concomitant treatment given to the patient. These narratives were reviewed by 2–3 faculty members of the Departments of Pharmacology and Medicine. After review and discussion, the suggestions by the expert faculty were incorporated, and AE narratives were finalized. The ADR reporting training module consisted of the finalized AE narrative, photograph of the AE, and ADR reporting form entitled “Suspected Adverse Drug Reaction Reporting Form” (SARF) version 1 of the PvPI.

Instruments

To assess students’ and faculty’s perceptions regarding given ADR reporting training module, questionnaires (15 items) were prepared after literature review [Tables 1 and 2]. The items in both the questionnaires were same, and responses were scored on Likert scale (5 – strongly agree, 4 – agree, 3 – neutral, 2 – disagree, and 1 – strongly disagree). The themes of the questionnaire were student satisfaction, module implementation, and acquisition of the skill to report ADR. Content validity of these questionnaires was checked by experts in medical education (n = 6). The questions which were agreed by more than three experts were included in the final questionnaire.

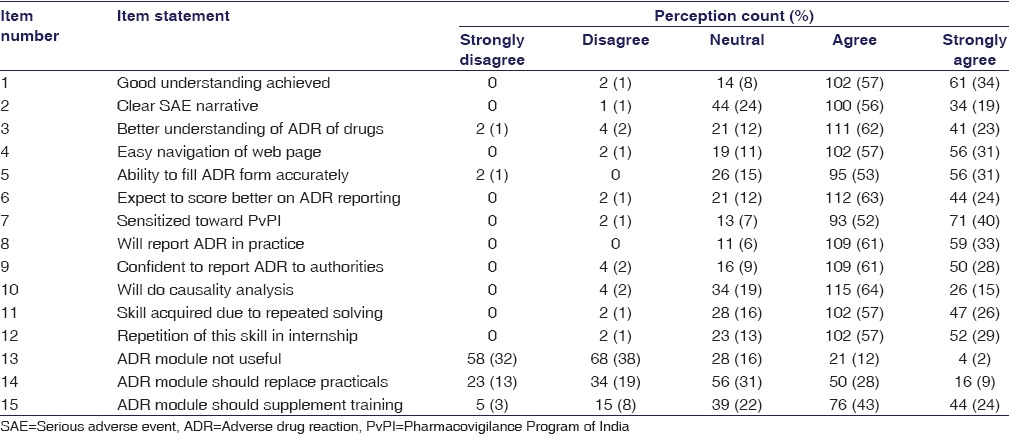

Table 1.

Student perception on 15-item feedback questionnaire of adverse drug reaction reporting skill using adverse drug reaction reporting training e-modules (n=179)

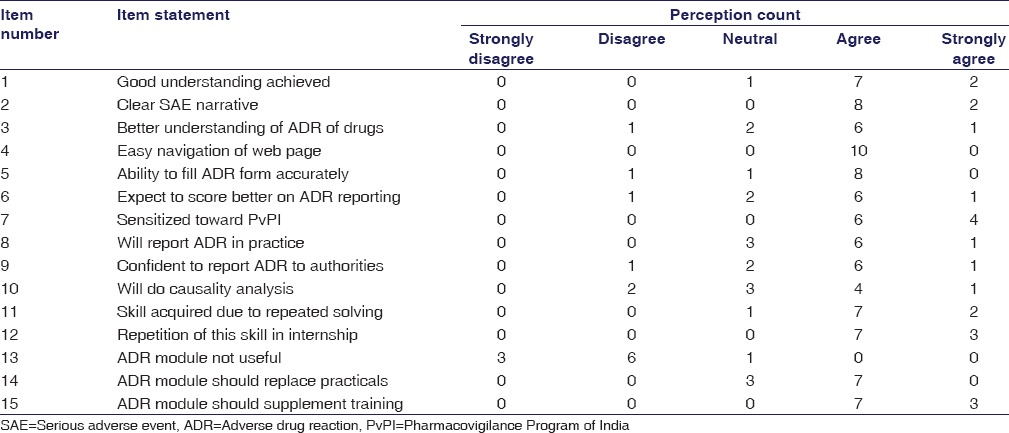

Table 2.

Faculty perception on 15-item feedback questionnaire of adverse drug reaction reporting skill using adverse drug reaction reporting training e-modules (n=10)

Assessment

The SARF of the PvPI was used as these budding doctors will, later on, use this form.[1] The authors introduced marks to each item of the SARF. Each item had a maximum score of 2 if the student filled it accurately. The score range was from 0 to maximum 36 (18 items were present in the form). The SARF e-mailed by the students was accessed by faculty and the responses checked for accuracy and total score was calculated. Thus, every student received ADR reporting performance score before the practical, 1 month and 6 months after the practical.

Teaching Learning Activity

In our department, theory lectures on ADR detection and reporting and a practical on ADR identification are being conducted. An additional practical on ADR reporting and monitoring was conducted as a part of this project. In this practical, students were briefed about the PvPI and an AE narrative was shared. During the conduct of the practical exercises, students were demonstrated how to transcribe the information from AE narrative to the SARF and fill the complete information as required by the PvPI. Every student was made to fill the SARF as part of the practical activity and place it in the practical record book.

In addition, ADR e-modules were prepared to reinforce the same and implemented. E-modules were decided to be developed as they are active and learner-centered, maintain the learner’s interest, provide a means for individual practice and reinforcement, thus offering a stronger learning stimulus than a traditional teacher-centered module.[8] The schedule of events is as given below.

Part I: Prepractical

The students who had consented were e-mailed the AE narrative, photograph of the AE, and SARF 7 days before the conduct of the practical exercise. Students were requested to fill the SARF and e-mail it back to the department.

Part II: Postpractical

Postpractical at 1 month and 6 months, students were e-mailed another AE narrative, photograph of the AE, and SARF. They were requested to fill the SARF and e-mail it back to the department. These SARFs were accessed online by faculty and performance score calculated for each student. These scores were communicated to the students, and in addition, the accurately filled SARFs for all the AE narratives were e-mailed to all the students. On completion of this module, student and faculty feedback was taken.

Modification in Teaching-learning Activity Postfeedback

The changes were introduced in the postpractical teaching-learning activity for the subsequent batch of students. Instead of e-mailing the SARF and asking students to fill online, a hard copy of the SARF was distributed to students and requested to fill the form in a weeks’ time and submit to the department. In addition, the following training sessions were introduced:

A training session as large group interactive lecture on how to fill the form and highlighting the common deficiencies/mistakes done by the students was conducted 1 month postpractical after students had submitted the filled SARF

A training session as small group discussion highlighting the mistakes done by the students on one-to-one basis was provided by the faculty 6 months postpractical after students had submitted the filled SARF.

Evaluation

The criteria for evaluation included number of students attempting the ADR module and e-mailing the duly filled SARF back to the department; performance of the student on ADR reporting skill before the practical, 1 month and 6 months after the practical; perception by faculty members who were involved/witnessed the ADR reporting e-module development and implementation and perception of students regarding the activity at the end of the second professional MBBS.

Statistical Analysis

The average performance scores obtained before the practical, 1 month and 6 months after the practical were compared by repeated measures of ANOVA with post hoc Tukey test. The perception questionnaires were analyzed using descriptive statistics. Data analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism version 5 statistical software (Graphpad software Inc., California, USA).

Results

The ADR reporting training module was implemented for the first time in the academic year 2012–2013. MBBS students in the third semester participated in the project. All consented students (n = 171) did fill the SARF before the practical; however, postpractical, this number decreased to 122 at 1 month, while at the end of 6 months, only 17 students attempted filling the SARF. The mean score of students before the practical was 16.2 ± 3.4 out of a total of 36 marks, which statistically increased at 1 month to 26.4 ± 2.6, (P < 0.01) and at 6 months to 27.3 ± 6.1 (P < 0.01).

Student feedback (n = 171) taken in their fourth semester revealed that only 10% students stated that good understanding was achieved as the AE narrative was clear and this also improved their understanding about ADR of drugs. Very few students (8%) stated that they were competent to fill the SARF and expected to score better on ADR reporting. Less than 4% students were sensitized toward PvPI, but nobody stated that they will report ADR in practice and will be able to do that confidently or do causality analysis. Majority of students (87%) stated that ADR module was not useful and stated that this module must be done in an internship. In the comments section, 77% students had opined that the timing of implementation of the module was not appropriate and e-mailing the SARFs at 1 month and 6 months coincided with the preparatory period for formative examinations. They also stated that although the correct answers were e-mailed to the students, it was requested that repeated training sessions are required on how to fill the SARF and deficiencies/mistakes should be highlighted.

Feedback from faculty (n = 10) also revealed that students were not interested in completing this module, had filled the SARF inaccurately, and in spite of repeated reminders, students had not responded to fill the SARF. Taking cognizance of this student-faculty feedback, the module was modified appropriately, and it was implemented for the students entering the third semester for the next academic year 2013–2014. The total number of students belonging to this batch who provided written consent and completed this module was 179. All students did fill the SARF before the practical and also postpractical at 1 month and at the end of 6 months. As regards filling SARF accurately, the student performance score before the practical was 10.5 (±5.2) which statistically increased at 1 month to 27.8 ± 3.6 (P < 0.01) and at 6 months to 30.3 ± 4.8 (P < 0.001 in comparison with before practical score). Similarly, the average number of students incorrectly filling the mandatory items of the SARF on these 3 occasions was 79.2, 41.5, and 19.7, respectively.

Similarly, in the feedback [Table 1] provided by the students of this batch (2013–2014), 91% stated that good understanding was achieved, the AE narrative was clear (75%), and this also improved their understanding about ADR of drugs (85%). The majority of students (84%) stated that they were competent to fill the SARF and 87% expected to score better on ADR reporting. Nearly 92% were sensitized toward the PvPI and 94% students stated that they will report ADR in practice and 89% will be able to do that confidently. Nearly 79% students opined that they will be able to do causality analysis. Majority of students (70%) stated that they disagreed that ADR module was not useful and 86% stated that this module must be repeated in an internship. The faculty feedback was also in similar lines as with the students [Table 2].

Discussion

In this study, the authors implemented an ADR reporting skill training module through practical and e-module for MBBS students in their fourth and fifth semesters. The first attempt received a poor response due to inappropriate timing of the program and inadequate training. Taking cognizance of critical feedback as it is an essential component for revamping any educational innovation, the authors modified the program and implemented it for the subsequent batch August 2013. The program now received a positive response as reflected from average performance scores and student feedback.

Because of the module, the majority of the students were sensitized toward the PvPI and at this point, did commit they will report ADR in future. This is similar to the perception of Nigerian medical students from Bayero University Kano, Nigeria, on ADR reporting, wherein 82% students strongly agreed that ADR reporting is the responsibility of health-care workers and stated that ADR reporting be taught in detail.[9] In a study done by Sivadasan and Sellappan,[10] final year Malaysian nursing students (67%) students also had opined that the ADR monitoring program of their country is essential and it is their duty to report ADR.

However, few students in our study had opined that they (nearly one-tenth) were not confident to report to the national authority, fill the form accurately, or do causality analysis (one-fifth). As regards performing causality analysis of an ADR, it is a skill in itself and requires different training than mere ADR reporting and filling the SARF accurately. Even half of the faculty members were of the similar opinion that medical students may not be able to perform causality analysis. The existing module did teach causality analysis in detail during the practical analysis, but separate sessions on this subtopic will help students in a better way, and in future, this training module must incorporate this topic too.

Another striking observation was nearly 30% students had reported that this ADR module was not useful. The reasons for this perception could be that immediate application and utility did not exist (as students were of the second year they will actually report ADR after a span of nearly 3 years) and neither was this activity linked to their assessment. A modular program extending across all the phases of MBBS and also preferably at postgraduate level as a continuum is essential. Such a program can incorporate ADR cases from the simple issues to complex therapeutic dilemmas that the students may encounter while practicing in real life. In addition, visit to the nearest ADR monitoring center and visualization of the after-ADR reporting activities by the students would also inculcate the importance of ADR reporting.

Students had perceived that repeated filling of SARF as part of the module and later in internship was essential. Internship reinforcement multiple times was vital as this would engrave in the students about voluntary ADR reporting and in future, add to the success of the PvPI. Rehan et al.[11] concluded in their study that resident doctors and nurses had good information and awareness on ADR reporting, and there is a need of improvement and reinforcement in their practices. This is similar to Gavaza et al.,[12] who concluded that majority of pharmacy students perceived that repeated reminders about reporting serious ADRs are essential. Even Hajebi et al.[13] concluded that it is necessary to offer continuous ADR-related educational programs until reaching the point that voluntary reporting of ADRs becomes conventional and habitual among nursing staffs.

From students’ perceptions in our study, it is evident that they are sensitized toward the PvPI, and looking at their performance scores, the students moved from novice stage to advanced beginner milestone in ADR reporting skill; still, their performance in our study is under supervision. Translation of this skill to proficiency stage in future and voluntary self-reporting ADR by them at a later stage cannot be predicted from our study. The faculty members were also skeptical as to whether students will report ADR in future though all faculty members agreed that due to this program, students were sensitized toward pharmacovigilance. After an extensive literature search, we did not find studies evaluating an educational strategy on ADR reporting in MBBS students; hence, the comparison of ADR reporting performance scores with other studies could not be evaluated.

Limitations of our study include that we could implement this program only at the second professional MBBS level. For any competency to be achieved in clinical practice, it is essential that the skill be reinforced at appropriate time intervals and difficulty level also must be changed. The module had three ADR cases; however, the difficulty level did not change much as it spanned only one phase. Although the performance of the students and number of students responding had increased, it cannot be ruled out that students may be doing it as a group activity and copying the information from their peers as against individual student filling the SARF accurately.

Thus, if all medical schools in India incorporate the ADR reporting skill in their curriculum, definitely future health-care professionals will be competent and confident in reporting the ADR. Even faculty of medicine and pharmacology has to be sensitized toward imparting training to the students in ADR detection and reporting. Although in our project, this skill was achieved only by the second professional MBBS students, this can serve as an example for the future development of ADR module and implementing it to the third-year professional MBBS and postgraduate students.

Conclusion

Training students on ADR reporting skill was effective using the module as the performance of students in filling SARF accurately increased which was coupled with less number of students making mistakes. The students and faculty did perceive that training undergraduate students in ADR reporting will result in effective reporting of ADR by them in their clinical practice. Educating MBBS students will produce health-care professionals competent in pharmacovigilance.

Financial Support and Sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank the faculty of the Department of Pharmacology and Therapeutics, Seth GS Medical College and KEM Hospital, Mumbai, for their support and cooperation to conduct this project.

References

- 1.Pharmacovigilance Programme of India (PvPI) [Last updated on 2014 June 13; Last accessed on 2016 Oct 08]. Available from: http://www.ipc.gov.in/PvPI/pv .

- 2.Pimpalkhute SA, Jaiswal KM, Sontakke SD, Bajait CS, Gaikwad A. Evaluation of awareness about pharmacovigilance and adverse drug reaction monitoring in resident doctors of a tertiary care teaching hospital. Indian J Med Sci. 2012;66:55–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khan SA, Goyal C, Chandel N, Rafi M. Knowledge, attitudes, and practice of doctors to adverse drug reaction reporting in a teaching hospital in India: An observational study. J Nat Sci Biol Med. 2013;4:191–6. doi: 10.4103/0976-9668.107289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rishi RK, Patel RK, Bhandari A. Under reporting of ADRs by medical practitioners in India-results of pilot study. Adv Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2012;1:1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Amrita P, Singh SP. Status of spontaneous reporting of adverse drug reaction by physicians in Delhi. Indian J Pharm Pract. 2011;4(Suppl 2):29–36. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Palaian S, Ibrahim MI, Mishra P. Health professionals’ knowledge, attitude and practices towards pharmacovigilance in Nepal. Pharm Pract (Granada) 2011;9:228–35. doi: 10.4321/s1886-36552011000400008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Upadhyaya P, Seth V, Moghe VV, Sharma M, Ahmed M. Knowledge of adverse drug reaction reporting in first year postgraduate doctors in a medical college. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2012;8:307–12. doi: 10.2147/TCRM.S31482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ruiz JG, Mintzer MJ, Leipzig RM. The impact of E-learning in medical education. Acad Med. 2006;81:207–12. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200603000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abubakar AR, Chedi BA, Mohammed KG, Haque M. Perception of Nigerian medical students on adverse drug reaction reporting. J Adv Pharm Technol Res. 2015;6:154–8. doi: 10.4103/2231-4040.165021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sivadasan S, Sellappan M. A study on the awareness and attitude towards pharmacovigilance and adverse drug reaction reporting among nursing students in a private university, Malaysia. Int J Curr Pharm Res. 2015;7:84–9. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rehan HS, Sah RK, Chopra D. Comparison of knowledge, attitude and practices of resident doctors and nurses on adverse drug reaction monitoring and reporting in a tertiary care hospital. Indian J Pharmacol. 2012;44:699–703. doi: 10.4103/0253-7613.103253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gavaza P, Brown CM, Lawson KA, Rascati KL, Wilson JP, Steinhardt M. Texas pharmacists’ knowledge of reporting serious adverse drug events to the food and drug administration. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2011;51:397–403. doi: 10.1331/JAPhA.2011.10079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hajebi G, Mortazavi SA, Salamzadeh J, Zian A. A survey of knowledge, attitude and practice of nurses towards pharmacovigilance in Taleqani hospital. Iran J Pharm Res. 2010;9:199–206. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]